University–industry interaction (U–I) acquires relevance to countries to the extent that they identify how scientific knowledge produced within universities enhances technological development in firms and facilitates innovations. Universities are invigorated by the possibility of new scientific investigations that these relationships provide. The objective of this article is to analyze the establishment and development of U–I interactions in Santa Catarina, Brazil, of four universities through evolutionary phases, forms of interaction, benefits, and barriers. A total of 38 in-depth interviews were conducted during the data collection stage. To support the analysis and presentation of results, the qualitative data analysis software Atlas/ti, version 7.1.3 was used. The results pointed to non-linearity in the evolution of U–I interaction and demonstrate that most of the relationships between universities and firms are concentrated in traditional and services channels. Moreover, their interaction intensity is evident in the short term with the flow of knowledge being directed from universities to firms. With regard to benefits and barriers, the research results expand on the avenues outlined in the literature, which reflects some characteristics of this interaction type in Brazil, whose relationships are still new and do not yet have a solid trajectory.

The study of university–industry interaction (U–I) has emerged as a specific research field in the last three decades as part of the increase in policies that emphasize the commercialization of research and the links between basic research and social needs (Bekkers & Freitas, 2008; Rothaermel, Agung, & Jiang, 2007; Teixeira & Mota, 2012). Published studies in this area are recent with a significant volume occurring in the period from 2000 to 2004. Their scientific roots come from fields related to management, business, and economics, showing the multidisciplinary nature of this area (Teixeira & Mota, 2012).

The importance given to the subject has generated a body of research that varies in perspective (university, company, government), structure (formal, informal), level of analysis (market, organization, individual), and effect (economic, academic, institutional, cultural, management) (Boardman & Ponomariov, 2009; Freitas, Geuna, & Rossi, 2012). The main themes studied in the area point to the knowledge transfer process and how this can be influenced by the characteristics of firms, universities, and researchers; the channels through which interaction occurs, the creation of spin-offs, the importance and role of intermediary agents, such as technology transfer offices; geographical questions (importance of location and spillover); the implications for science and technology policy, and the measurement of U–I cooperation (Teixeira & Mota, 2012).

Interest in this field of study has also been stimulated by the rapid growth of research related to the National System of Innovation (NSI) and other similar focuses, such as technology transfer, licensing and patenting, non-linear innovation, the ivory tower, and the triple helix (Gulbrandsen, Mowery, & Feldman, 2011; Lee, 2000; Teixeira & Mota, 2012). This literature emphasizes the importance of interactions and institutional arrangements, seeing universities as actors that can contribute to economic development in knowledge-based economies. Within the NSI, universities can establish links with productive structures that allow the acceleration of the transfer of knowledge and technology (Mowery & Sampat, 2007).

Many countries have implemented policies to strengthen interactions between universities and firms in order to achieve better economic performance supported by academic research (Tartari & Breschi, 2012). Such policies in many cases involved changes in legislation, creating support mechanisms that encourage U–I interaction in the belief that firm innovation requires academic research (Gulbrandsen et al., 2011). Similarly, firms have been increasing the pressure for academic researchers engaged in projects with commercial partners (Arza, 2010).

In Brazil, the NSI occupies a median position globally along with countries such as Mexico, Argentina, South Africa, India, and China (Fernandes et al., 2010; Rapini et al., 2009). Suzigan and Albuquerque (2011a, p.18) report that “an important component of the developed innovation systems is limited: a strong interactive dynamic between firms and universities…that would provide positive feedback loops between scientific and technological dimensions”.

Research on U–I interaction is an area that has been explored in the country with notable contributions on the historical roots of U–I interaction in Brazil (Suzigan & Albuquerque, 2011a; Suzigan & Albuquerque, 2011b); U–I interaction based on Research Groups in the Brazil Directory of the National Research Council (PGD-CNPq) (Rapini & Righi, 2006; Rapini & Righi, 2007; Rapini, 2007; Righi & Rapini, 2011); technological intensity (Pinho, 2011); geographical proximity (Costa, da Ruffoni, & Puffal, 2011; Garcia, Araújo, Mascarini, & Santos, 2011); industry standards (Britto & de Oliveira, 2011); the sources of funding (Rapini, de Oliveira, do Couto, & Neto, 2013); and studies with regional samples that include Santa Catarina (Cario, Nicolau, Fernandes, Zulow, & Lemos, 2011; Cario, Lemos, & da Simonini, 2011).

In general, the literature on U–I interaction in Brazil points to the existence of only localized points or “interaction spots” (Albuquerque, Suzigan, Kruss, & Lee, 2015; Albuquerque, 2003; Rapini, 2007; Righi & Rapini, 2011; Suzigan & Albuquerque, 2011a). These points refer to specific sectors and areas where U–I interaction functions in a systematic and consolidated manner. They have their origins in cooperation incentives, sectoral policies, the formation of knowledge and technology-intensive sectors, the stimulation of scientific production, science funding, and the scientific community's interests in relation to certain sectors (Righi & Rapini, 2011).

Interaction spots are the result of the historical process of the late establishment of universities in Brazil and the country's pattern of industrialization, which lays the foundation for understanding the U–I interaction phenomenon. In Santa Catarina, a movement similar to the national standard is seen. In relations to U–I interaction, Santa Catarina state has the seventh largest number of research groups in Brazil, and, of all groups registered in the CNPq in the 2010 Census (i.e., 1263 groups), 18.92% have relations to industry. This is higher than the national average—which is around 12.74%—and the highest percentage for all Brazilian federal states (CNPq, 2013).

This article aims to broaden the debate on the theme and contribute information that supports discussion about policies and actions in the State System of Science, Technology, and Innovation of Santa Catarina. Science, technology, and innovation policy in Santa Catarina has expressed the need to strengthen S&T institutions (such as universities), as well as increase interactions between such institutions and local production arrangements (i.e., firms).

The overall objective of this study is to analyze the establishment and development of U–I interactions in Santa Catarina. The text is organized into five sections, including this introduction. The second section presents a theoretical review that contemplates aspects of U–I interaction processes in categories of analysis. The methodological procedures are described in the third section. In the fourth section presents research results, organized into analysis categories: evolutionary phases, interaction formats, and benefits and barriers. The fifth section closes with final remarks.

Process U–I interactionThe process that generates innovations is complex because it depends intrinsically on elements related to knowledge that translate into new products and processes, which are embedded in an environment characterized by feedback mechanisms and interactions involving science, technology, learning, production, policy, and demand (Edquist, 1997). Therefore, it must be noted that although most innovations happen inside innovative firms, other institutions such as universities, government laboratories, and coordinating and financing agencies of the government play a key role in the creation of new technologies (Niosi, Bellon, Saviotti, & Crow, 1992).

In this view, a systemic view of innovation is developed that emphasizes the role of interactions between the agents involved in innovation processes and institutional arrangements that create conditions for the competitiveness of a country, distinguishing it from others (Freeman & Soete, 2008). Both universities and firms vary greatly in the extent to which they engage in projects that promote the commercialization of academic research as well as the extent that such mechanisms are shown to be successful or not, because even within countries there are great levels of heterogeneity in approaches taken by universities when interacting with firms (Geuna & Muscio, 2009). Thus U–I interaction is set in a learning process, both by the university and the firm, whose relations are established within a logic that involves the sharing of knowledge, mutual trust, and the transfer of personnel between the two actors (Albuquerque et al., 2015).

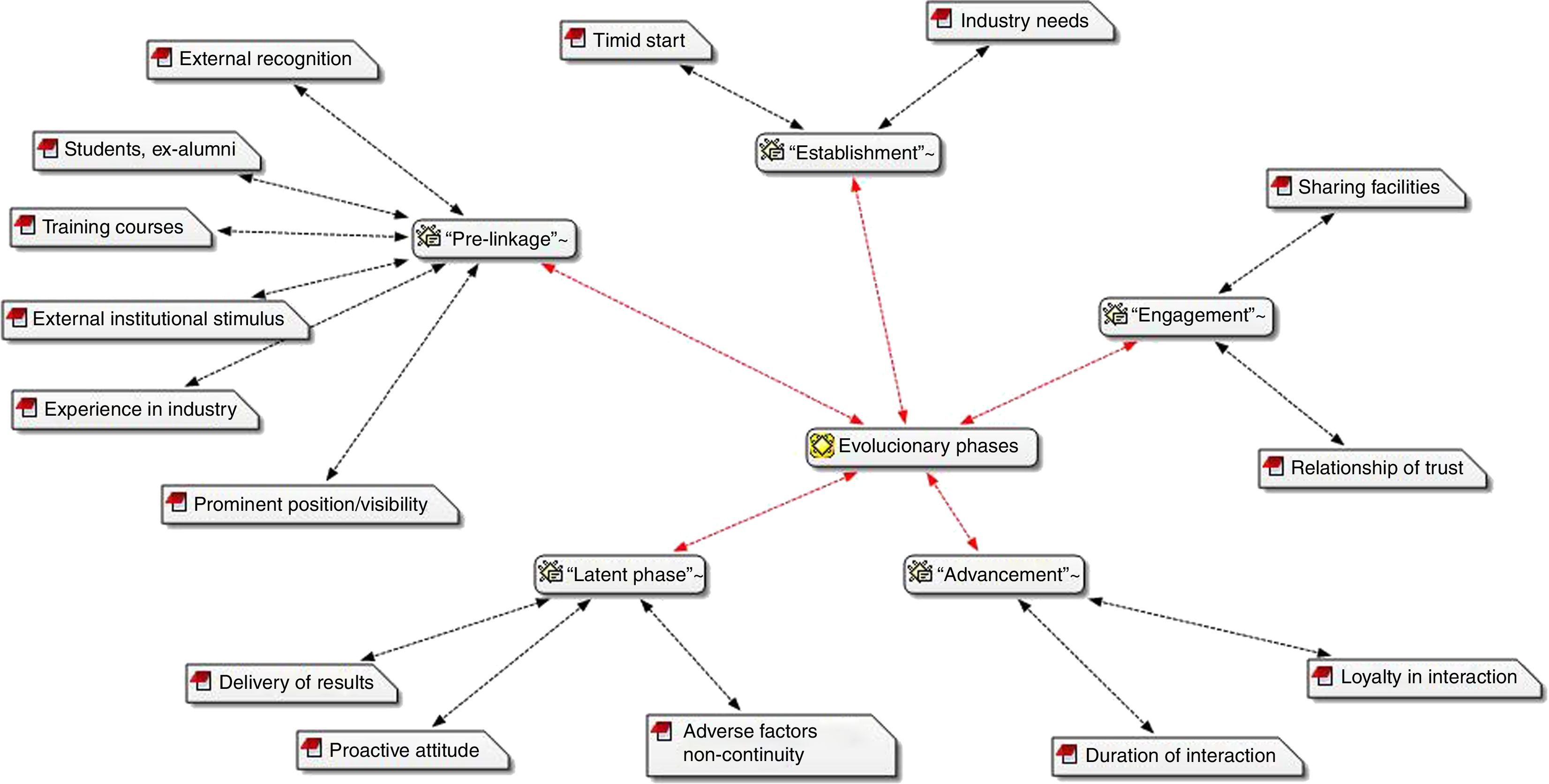

Plewa et al. (2013) define the dynamics of U–I interaction and show the different phases through which relationships evolve. They note that such development does not necessarily follow a linear path, but varies according to intensity and involvement. The first phase is “pre-linkage” and is characterized by the identification of individuals or teams as potential research partners, which is strongly influenced by the networks that researchers are involved in; the “establishment” phase is where more concrete discussions are initiated, which aim to better understand strengths, needs, and interests of each party, concluding with the signing of a contract/agreement; the “engagement” phase involves the development of processes and mechanisms for the establishment of a collaborative environment in order to work on specific projects; in the “advancement” phase, the sustainability of the relationship and the delivery of specific projects are developed; and the final “latent” phase consolidates the continued partnership and opens the door for future cooperation.

In this evolutionary process, links between universities and firms are established, which can take several forms: “mechanisms” (Meyer-Kramer & Schmoch, 1998), “channels” (Cohen, Nelson, & Walsh, 2002; D’este & Patel, 2007; Dutrénit & Arza, 2010), or “links” (Ahrweiler, Pyka, & Gilbert, 2011; Perkmann & Walsh, 2007). Regarding mechanisms, Meyer-Kramer and Schmoch (1998) connect collaborative research, informal contacts, staff training, theses, research contracts, conferences, consultancy, seminars for industry, exchange of scientists, publications, and committees. For channels, Cohen et al. (2002) cite publications and reports, informal interaction, public meetings and conferences, contract research, consultancy, joint and cooperative ventures, patents, personnel exchanges, licenses, and the hiring graduates.

D’este and Patel (2007) place interaction channels into five broad categories, including meetings and conferences, consultancy and contract research, creating spin-offs and physical facilities, training, and joint research. Perkmann and Walsh (2007) suggest the following typology for U–I links: research partnerships, research services, academic entrepreneurship, human resource transfers, informal interaction, commercialization of property rights, and scientific publications.

Ahrweiler et al. (2011) mention formal links: contract research, joint supervision of master and doctoral students, licensing patents from universities to firms, co-publications, co-patenting, purchasing of prototypes developed in universities, contract consultancy, the formation of spin-offs, training and professional development of employees at universities, the use of university libraries, laboratories, and other facilities by firms; deployment of joint staff, joint research programs, and collaborative R&D. And informal links: meetings, e-mail communication, and joint participation in seminars and conferences.

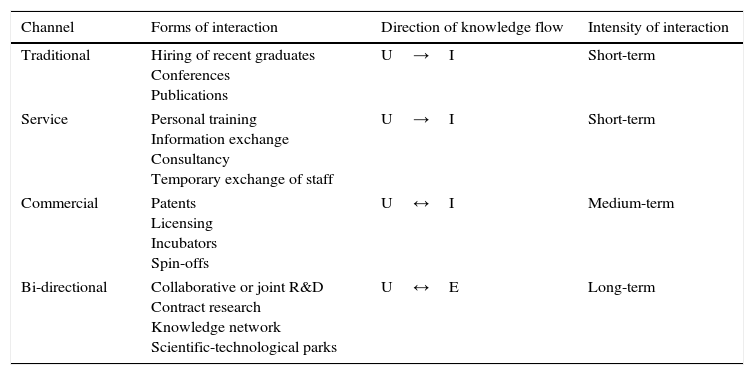

Complementing the previous information, Dutrénit and Arza (2010) put interaction channels into four categories that show the form of interaction, knowledge flow direction, and interaction intensity, as can be seen in Table 1.

Channels and forms of university–industry interaction.

| Channel | Forms of interaction | Direction of knowledge flow | Intensity of interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Hiring of recent graduates Conferences Publications | U→I | Short-term |

| Service | Personal training Information exchange Consultancy Temporary exchange of staff | U→I | Short-term |

| Commercial | Patents Licensing Incubators Spin-offs | U↔I | Medium-term |

| Bi-directional | Collaborative or joint R&D Contract research Knowledge network Scientific-technological parks | U↔E | Long-term |

Another aspect of U–I interaction relates to the question of the benefits that the relationship can bring to both parties. Through interactions with universities, firms can obtain various types of benefits that contribute to their learning capability. Interaction can stimulate learning and drive advances in new technologies (Betts & Santoro, 2011); interaction can contribute to the implementation of long-term innovation strategies through the development of new capabilities (Dutrénit & Arza, 2010); academic research can help firms increase understanding of the foundations of a particular phenomenon and envision new opportunities, especially when the results of research directly affect innovation (Bishop, D’este, & Neely, 2011; Klevorick, Levin, Nelson, & Winter, 1995); interactions with universities can strengthen the capability of firms to exploit new and/or existing knowledge and the flow of ideas, in order to create new products and processes or to reduce costs in the development of existing products and processes (Bishop et al., 2011; Mueller, 2006); and the proximity between people from universities and firms can increase problem-solving capabilities and facilitate the recruitment of qualified staff (Bishop et al., 2011; Dutrénit & Arza, 2010; Meyer-Kramer & Schmoch, 1998).

From the perspective of universities, the following motives for engagement and collaboration with firms can be identified: commercialization, through the commercial exploitation of knowledge or seeking business opportunities; learning, with the completion of academic research together with firms, the possibility of putting theory and research into practice, as well as more knowledge into research; access to funding, complementing public research with private funding and other resources, such as equipment, materials, and research data; dissemination of the university's mission; and creating internships and placement opportunities for students (D’este & Perkmann, 2011; Lee, 2000).

From the point of view of researchers, Dutrénit and Arza (2010) and Arza (2010) emphasize intellectual benefits (reputation, access to new ideas and projects, inspiration for future research) and economic benefits (access to additional resources, equipment, instruments, laboratories, supplementing personal income).

The barriers to U–I interaction must also be addressed. On this subject, Bruneel, D’este, and Salter (2010) classify two basic types: “orientation-related barriers”, which refers to differences in the orientation between universities and businesses; and “transaction related- barriers”, which deals with conflicts over intellectual property and modes of university management. Lhuillery and Pfister (2009) also add some barriers to this classification.

These include universities’ strong emphasis on pure science, while firms are usually interested in applied research; the long-term orientation of academic research (university researchers have a lesser sense of urgency than corporate researchers); the lack of mutual understanding of expectations and work practices; and differences in incentives for university researchers and business professionals, with the former regularly being guided more by scientific values than market values. In the second case, there are unrealistic expectations for research and results; potential conflicts arising from the payment of royalties generated by patents and intellectual property rights—in addition to concerns about confidentiality; researchers want to publish research results while business professionals are more interested in keeping them secret; rules and regulations imposed by universities or government funding agencies; and the absence or low profile of offices promoting links between the firm and university.

The discussion on orientation barriers should be broadened. Maculan and Mello (2009) argue that universities assume activities that are close to their ethos more easily, that is, those that represent a natural extension of teaching and research. The authors add that moving beyond these traditional activities to implement complex internal mechanisms and significantly changing the culture and values of academia are essential.

Discussion of hybrid organizations begins at this point, which according to Davidson and Lamb (2004) operate in the boundaries between academic research and commercial research and development (R&D). These appear in the form of technology transfer offices, cooperation agreements, commercial enterprises run by scientists, and commercial firms participating in funded research. Hybrid organizations look to combine the institutional logic of each actor involved in the relationship—in this case universities and businesses—creating a set of practices that fit the demands of their environment and leveraging far reaching support (Pache & Santos, 2011). Hybrid organizational forms enable institutional pluralism, selectively joining elements from two logics, within the constraints imposed by their need for legitimacy (Pache & Santos, 2013).

Methodological proceduresThis research takes a qualitative approach as it is more appropriate for studying the phenomenon in question and allows a deeper analytical and reflective understanding of the particularities involved in U–I interaction. According to Denzin and Lincoln (2006), “qualitative” implies an emphasis on the qualities of entities and significant processes, especially with regards to socially constructed reality, where a close relationship between the researcher and their object of study is established.

This research also takes on a descriptive and explanatory character. Descriptive research aim to describe the features of a population or phenomenon, or establish correlations between variables, while explanatory research seeks to identify elements that contribute to the occurrence of certain phenomena (Gil, 2008; Vergara, 2009). In this case, the process of U–I interaction is being described in relation the actors involved whilst seeking elements to explain the identified relationship patterns.

Moreover, bibliographic and documental researches in addition to field research (Gil, 2008) were used in this study. Bibliographic research included books on the theme and relevant articles mainly found in databases available in the journals from CAPES (an online Brazilian publication portal), using the keywords “university” and “firm”. Another part of the investigation involved researching documents produced on the system of higher education in Santa Catarina, such as management and activity reports, strategic planning, statistics, and overviews of legal instruments. Field research involved empirical investigation into the phenomenon in universities.

The focus of analysis proposed in the research was from the perspective of the university. Although the situation under study involves two players (the university and the firm), portraying just the point of view of the university was opted for. According to Boardman and Ponomariov (2009) and Freitas et al. (2012), there is a large body of work on the study of U–I interaction and one of the techniques was researching from the perspective of actors—in this case the university.

From this definition, we selected a sample to research the higher education system in Santa Catarina. We used data from the following database systems to support the research: the National Institute for Educational Research (INEP, 2012), the National Research Council (CNPq, 2013), and a geo-referenced information system of CAPES (CAPES-GEOCAPES, 2012). First, Santa Catarina's higher education system and administrative categories of the state's institutions were considered. In addition, graduate-related data and research activities in Santa Catarina of particularly relevance to this research were studied, since relations established between universities and firms are usually from contacts that are created from research groups.

According to the data consolidated by INEP (2012), Santa Catarina has 99 higher education institutions (HEIs) including universities, university centers, colleges, and federal institutes. Among these, 18 are public HEIs, 4 federal, 1 state, 13 municipal, and 81 are private. From the institutions of the southern state of Brazil, 36.7% are public and 22.5% are private.

Data from CAPES-GEOCAPES (2012) show that, from the 130 existing graduate programs in Santa Catarina; 67% belong to UFSC (the Federal University of Santa Catarina, 21% are connected to UDESC (the State University of Santa Catarina); 10% belong to FURB (the Regional University of Blumenau); and 9% to UNIVALI (Vale do Itajai University), which respectively represent the four institutions with the highest number of graduate programs in the state, a total of 82.3%.

With regard to research, the 2010 DGP-CNPq (Directory of Research Groups of CNPq) Census (CNPq, 2013) shows that from the 90 institutions with the largest number of research groups in the country, 4 are from Santa Catarina: UFSC in 7th place, with 514 groups; UDESC in 54th, with 136 groups; FURB in 84th, with 88 groups; and UNIVALI in 88th place, with 84 groups. This means that 65.08% of the total research groups in the state are concentrated in these four institutions. The institutions and their groups have 5594 researchers and 8599 students, equivalent to 63.49% and 79.95% of all researchers and students involved in research groups in Santa Catarina. Other relevant data relate to research groups that have a relationship with industry. In 2010, first place was occupied by UFSC, with 97 groups; followed by FURB, with 23 groups; UDESC, with 19 groups; and UNIVALI, with 16 groups. These numbers represent 64.85% of the interacting groups in the state.

From this information, it was decided that these four universities—UFSC, UDESC, FURB, UNIVALI—should be the object of study, as their postgraduate and research dynamics are the most significant in Santa Catarina. Furthermore, these universities belong to different administrative categories—federal, state, municipal, private—giving a broader range for analysis of different policy views, administrative flows, and internal procedures. We therefore have a non-probabilistic sample of typicality, which according to Vergara (2009, p. 47) “consists of the selection of elements that the researcher considers representative of the target population”.

Based on the 2010 Census data of DGP-CNPq (CNPq, 2013), data collection focused on the leaders of research groups that maintain a relationship with industry and the managers of technological innovation centers (TICs) of the universities. Contact was made by email in order to request interviews, which sought to cover research groups from a range of subject areas.

A total of 38 in-depth interviews were carried out, whose average duration was 50min. Interviews were conducted in person with the exception of one that was done via skype. All were recorded with the consent of respondents and later transcribed. A total of 11 questions for the in-depth interviews were developed using the pre-set research analysis categories.

Field research involved 31 groups identified in the research as GP1 to GP31. In relation to the leaders, 17 are from UFSC, 5 from FURB, 5 from UDESC, and 4 from UNIVALI. Knowledge and subject areas included 6 groups from agricultural sciences, 1 group from biological sciences, 2 groups from health sciences, 5 groups of exact sciences, 5 groups from applied social sciences, and 13 groups from engineering. A total of 7 TIC managers were interviewed, who were either current or former managers.

Data saturation criterion was used, which, according to Gibbs (2009), is when data predictions based on existing categories of analysis are repeatedly confirmed, indicating that data collection can be halted. Thus, from the moment that the information began to repeat itself, with no more data being added to the categories of analysis, data collection was stopped. In this process, a total of 20% of all interactive groups in the four universities were investigated.

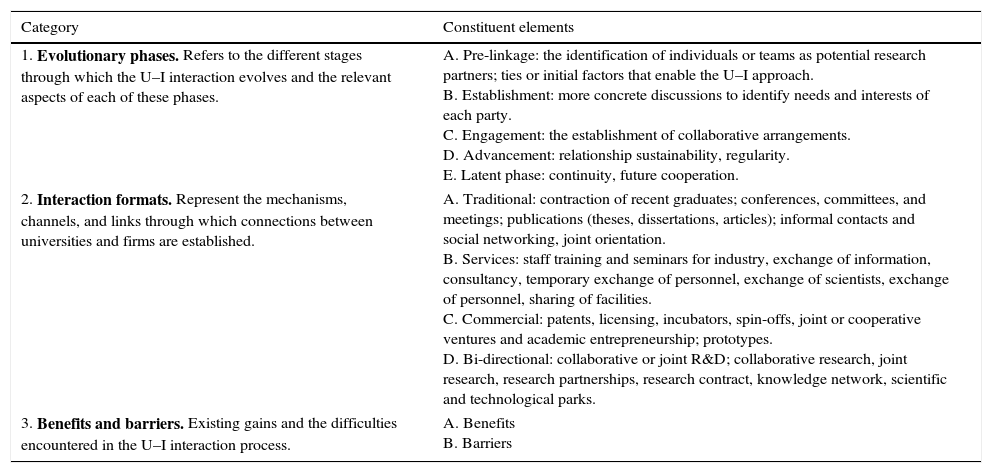

Categorical content analysis was employed using the categories of analysis described in Table 2. The qualitative data analysis software Atlas/ti, version 7.1.3 was used to support the analysis and presentation of results. Graphics were generated (network views) showing an illustration of the relationship between collected data and their organization in categories.

Categories of analysis.

| Category | Constituent elements |

|---|---|

| 1. Evolutionary phases. Refers to the different stages through which the U–I interaction evolves and the relevant aspects of each of these phases. | A. Pre-linkage: the identification of individuals or teams as potential research partners; ties or initial factors that enable the U–I approach. B. Establishment: more concrete discussions to identify needs and interests of each party. C. Engagement: the establishment of collaborative arrangements. D. Advancement: relationship sustainability, regularity. E. Latent phase: continuity, future cooperation. |

| 2. Interaction formats. Represent the mechanisms, channels, and links through which connections between universities and firms are established. | A. Traditional: contraction of recent graduates; conferences, committees, and meetings; publications (theses, dissertations, articles); informal contacts and social networking, joint orientation. B. Services: staff training and seminars for industry, exchange of information, consultancy, temporary exchange of personnel, exchange of scientists, exchange of personnel, sharing of facilities. C. Commercial: patents, licensing, incubators, spin-offs, joint or cooperative ventures and academic entrepreneurship; prototypes. D. Bi-directional: collaborative or joint R&D; collaborative research, joint research, research partnerships, research contract, knowledge network, scientific and technological parks. |

| 3. Benefits and barriers. Existing gains and the difficulties encountered in the U–I interaction process. | A. Benefits B. Barriers |

As noted by Plewa et al. (2013), U–I interaction reveals a dynamic with striking features that can be grouped into distinct phases that identify progression, although there is not necessarily a linearity in this process. The authors identify certain important moments through these phases, which are used here to characterize the evolution of relationships established by research groups with firms. Thus, identification is proceeded by characteristic features of each of the stages of the U–I interaction evolution: pre-linkage, establishment, engagement, advancement, and the latent phase.

For the pre-linkage phase, the common situation for establishing contacts with firms through students, ex-alumni, or professors who already have ties to such firms. Typically, students or former students know the expertise of the field in question, know the professors, and know what the university can offer when approaching firms. Professors also identify—whilst in contact with these professionals—approach opportunities, as reported by one researcher: “So I started and was the first interaction, only because a student who came to me worked in a company, and then we started to expand” (GP11).

There is also approximation and contact through students offering training or graduate courses to specific firms. Training courses are offered can be offered in an in-company form, which are designed for firms with specific demands; or in open course format, which focuses on specific topics of interest to several firms. Graduate courses refer to those offered within the portfolio of universities. Mowery and Sampat (2007) add that this mechanism is important for the dissemination of scientific research, in addition to the fact that demands of students and their employers help strengthen ties between university research agendas and societal needs.

The relationship established between market professionals and researchers through such courses allows the identification of problems that can lead to research projects or provide grounds for experimenting with concepts. Thus, these two aspects generate opportunities that can result in innovations that would not have otherwise been accessed. The following statement illustrates this point: We had a case in which we had brought a theme to the firm; we had not realized how innovative and important it was to them and we were not working on behalf of the university on this matter. We had to join five, six specialist professors who spent two years putting in the ground work. Now we have 20 years of research in front of us, a challenge brought by the industry (GP7).

Another noticeable aspect is the case where the researcher, before joining the university or concurrently, has or had some experience in industry and continued to maintain contacts, generating interaction. Moreover, there are some cases where the contacts are fostered by an external institutional stimulus. Among these stimuli include those promoted by government entities, such as commissions for conducting joint research; sectoral funds, especially with a “yellow-green fund”, whose goal is precisely to promote U–I interaction; and also innovation incentive programs, such as SIBRATEC and INOVA. Contextual variables are also included, such as geographical proximity, an interest in a certain subject or field of research, and successful models for U–I partnerships.

It was also frequently observed that the university or researcher holds a prominent position, which naturally gives visibility. As stated by one respondent: “It is usually the firm seeking the university … our university has featured on the national scene and is well recognized … It is among the five best in the country, so we have a good name out there” (GP6).

In the establishment phase, it is clear that many groups had timidly started relationships with firms that tended to become consolidated over time. The beginning of the partnership is marked by a relationship with two to three firm and usually involves pre-defined activities, such as product feasibility analysis, completion of the development of course work or dissertations, or participation in public notice together with firms in order to search resources for the group. There is a great deal effort on the part of the researcher to transform the relationship with the firm into a concrete joint proposal, which effectively results in a formalization of the process and returns, especially financially.

In the phase engagement, is it possible to see the strategies adopted by research groups for the establishment of an environment based on collaboration between the parties. One point to highlight in this regard is the question of sharing facilities between the parties, creating an atmosphere of cooperation: “[T]here is a firm that offers us infrastructure and we, for example, implemented new assortments, we test and evaluate quality, so, there is a relationship of exchange” (GP1).

Another point observed in this phase is the concern of establishing a relationship of trust in which the logic of the university and the firm are preserved. This concern is due to the fact that the firm and the university's way of operating is different, especially with regard to structure, culture, decision making, and orientation toward results. This requires each of the parties to properly assimilate these different modes, as can be seen in these cases: “[T]he firm has to understand how the university is and we have to understand how they are, and respect how the work is going” (GP14). “[T]he dynamics of the company is one thing and the university is something else entirely. We showed them that our dynamic is different and they understood” (GP21).

This translates into a view of commitment between the parties, which is critical in a process that involves risks and uncertainties, such as the environment that permeates research activities. Bruneel et al. (2010) state that trust in relationships is important to the establishment phase, especially because the process of research and innovation is surrounded by many unknowns with regard to results.

Regarding the advancement phase, relationship sustainability has a clear link with the duration of interaction. In this sense, there are research groups whose ties to industry have lasted for several decades. This fact is related to how long a research group has been together, as well as their track record of performance. As most research groups were formed in the 2000s, there is still a consolidation process occurring for groups’ research and their performance.

Previous collaborative research becomes relevant in this case because, as shown in the literature, as researchers with a past history of interaction are more likely to engage in a wider variety of projects with firms, expanding interaction channels through which they connect (D’este & Patel, 2007). Hence, a virtuous circle is created in which interaction fosters more interaction.

Finally, the latent phase relates to research groups behaving in a way to ensure the continuity of interactions and seeking future cooperation. The delivery of results of joint work reflected in the preparation of detailed reports and meetings to present results as well as searching for new opportunities is important in this respect. The proactive attitude of researchers in expanding actions by working together with firms is also vital.

The development of systematic relationship that occurs in the long term was also observed, an effect that is dependent on the history and course of the research group. In this regard, it should be noted that of the 31 groups participating in the research, 20 were created in 2000, 7 groups were formed in the 1990s, 3 groups in the 1980s, and one group in the 1970s. The cases in which partnerships are continued and consolidated come from groups that have been together longer, that is, the two groups created in the 1980s and a group created in the 1990s.

It must be noted that adverse factors such as changes in direction or structure of firms can result in the non-continuity of interactions—issues that are not in the control of researchers. As stated Plewa et al. (2013), this could be due to a lack of funding, projects or research becoming less relevant, or simply due to there being a lack of will for joint work. The main aspects of each of the evolutionary phases of the U–I interaction can be seen in Fig. 1, which summarizes the key points of this category of analysis.

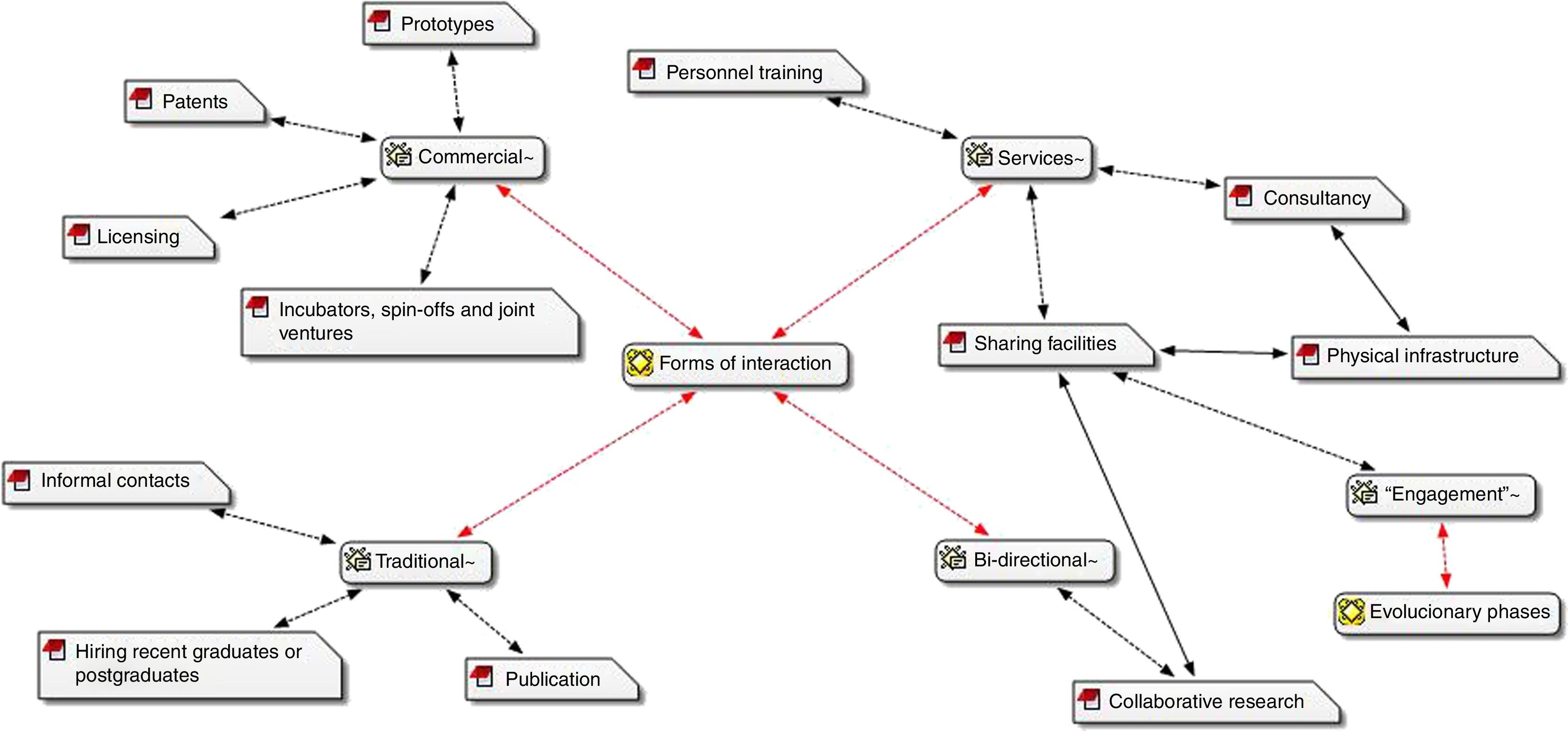

Forms of interactionThe forms of interaction between universities and firms can be through mechanisms (Meyer-Kramer & Schmoch, 1998), channels (Cohen et al., 2002; D’este & Patel, 2007; Dutrénit & Arza, 2010), or links (Ahrweiler et al., 2011; Perkmann & Walsh, 2007). To analyze the forms of interaction, the general classification of Dutrénit and Arza (2010) was employed, which identifies four main channels: traditional, services, commercial, and bi-directional. In each of these channels, forms of interaction proposed by the authors were considered, adding to the additional proposals of the authors mentioned above.

The traditional channel involves the following possibilities: hiring recent graduates, conferences and committees, publications, informal contacts, and social networks. Given these possibilities, publication proved to be the most common form among researchers, particularly theses and dissertations produced from interactions with firms in situations where firm demands align with to-be-developed post-graduate works, as demonstrated by the following excerpt: “We now have people who study exactly the same theme as their industrial project, something that did not exist in the past” (GP7).

Furthermore, it appears that hiring recent graduates or postgraduates is a common practice. Informal contacts are also frequent and typically occur because the researcher is well known. In addition to more personal forms of contacts, communication by telephone and other means are also common.

Conferences and committees as well as the joint ventures were not mentioned by respondents as forms of interaction. However, several references were made to the traditional teaching, research, and extension roles of universities as ways in which firm relationships are founded. It was identified that researchers attribute different roles to the university and the firm in interactions; the former generates knowledge to be absorbed by the industry whilst the latter is the materialization of knowledge in products.

The services channel includes personnel training, seminars for industry, and other types of skill building; the exchange of information, consultancy, the temporary exchange of personnel, such as scientists and staff; and facility sharing. It should be noted, first, that the provision of services as a whole is the firm interaction channel most referenced by respondents, with consultancy being the most common form. The most apparent characteristic was that services provision happened in a defined time period and was short term. Many of the firms establishing relationships with universities made specific demands or have specific problems that cannot be solved through internally held knowledge. Usually this situation is set through initial interactions, which can then develop into further collaboration.

Another aspect relates to consultancy as a form of interaction that serves small firms, which usually do not have their own research or R&D structure. This research is in agreement with Perkmann and Walsh (2007) in arguing that consultancy is relevant to small- and medium-sized enterprises since most of them do not pursue formal R&D, reinforcing that extension activities of universities can have positive impacts on innovation activities of local businesses.

Some researchers consider it important to limit this type of activity within the research group. This is because they understand that it absorbs much time and effort that could be otherwise channeled to other forms of interaction, which would allow for more research advances in groups’ lines of work. One possibility is the inclusion of junior firms in consultancy, which would meet the demands that the groups have no interest in or cannot attend.

The sharing of facilities normally occurs because of mutual interests in obtaining complementary infrastructure. In this sense, there is usually more use of firm premises, as illustrated in this case: “Basically we use the business facilities, we assemble the experiments with firm plants; there are 10-year experiments there” (GP27). As for universities, in another case: “[S]o now we have set up a laboratory to do tests within the university and perform parts of the innovation process, then take them out afterwards” (GP31). However, the practice of sharing facilities goes beyond this and also feeds joint research, a mode of interaction that is bi-directional, as will be seen below.

With regard to the provision of services, personnel training in universities organized by research groups was a common phenomenon, either through extension activities, opens to the community, or through actions designed to meet specific firm needs.

Some reflection on the provision of services by research groups as a whole is needed. Apparently, this modality is set like a generic channel of interaction with firms. Providing services is easier through the legal instruments available to universities, but relationships often evolve to other types of interaction that have greater regularity and longer durations, when other forms of interaction begin to start. However, not all research groups are able to reach these more mature stages.

The commercial channel includes the following considerations: patents, prototypes, licensing, incubators, spin-offs, joint and cooperative ventures, and academic entrepreneurship. The research saw that this item had little consistency in relation to the mentioned processes; it is possible to recognize the perception of some respondents about the relevance of the area, but few actions were concrete or effective. On this subject, the reporting of difficulties was common (e.g., bureaucracy), which need to be overcome if firm interaction channels are to be leveraged.

For patents, several cases were mentioned where there was a view of registering certain projects that are being developed, although few patents were granted. Licensing follows a similar practice, but was mentioned less often. Regarding prototypes, few groups referred to the type of process, reinforcing the complexity involved.

Incubators, spin-offs, and joint ventures are still at an incipient stage. Three research groups demonstrated that they functioned as incubators for firms born from former students, and in two cases in conjunction with professors. Such developments were created from the know-how developed within the group and in view of defined market segments.

In the bi-directional channel, there are collaborative R&D or joint forms of interaction, including collaborative research, joint research, and research partnerships; contract research, knowledge networks, and scientific and technological parks. The research identified weaknesses in relationships, practically restricting this form to groups whose interaction with industry is longer. This issue also goes toward what was previously mentioned about firms not having a tradition in this type of relationship, and when they seek universities it is usually to solve specific problems in the short term.

Research carried out in conjunction with firms was essentially seen as joint research, cooperative research, R&D, or joint development by researchers. There are instances where this type of relationship is mainly due to the sharing of facilities—an aspect reinforced by the engagement phase—with the establishment of a collaborative environment also being mentioned.

Fig. 2 displays the main forms of interaction according to their classification. Interestingly, the sharing of facilities is part of the service channel but is directly linked to collaborative research, which is part of the bi-directional channel. The figure also shows the connection of this analysis category with the evolutionary phases, where the sharing of facilities is an important point for establishing collaboration in the engagement phase.

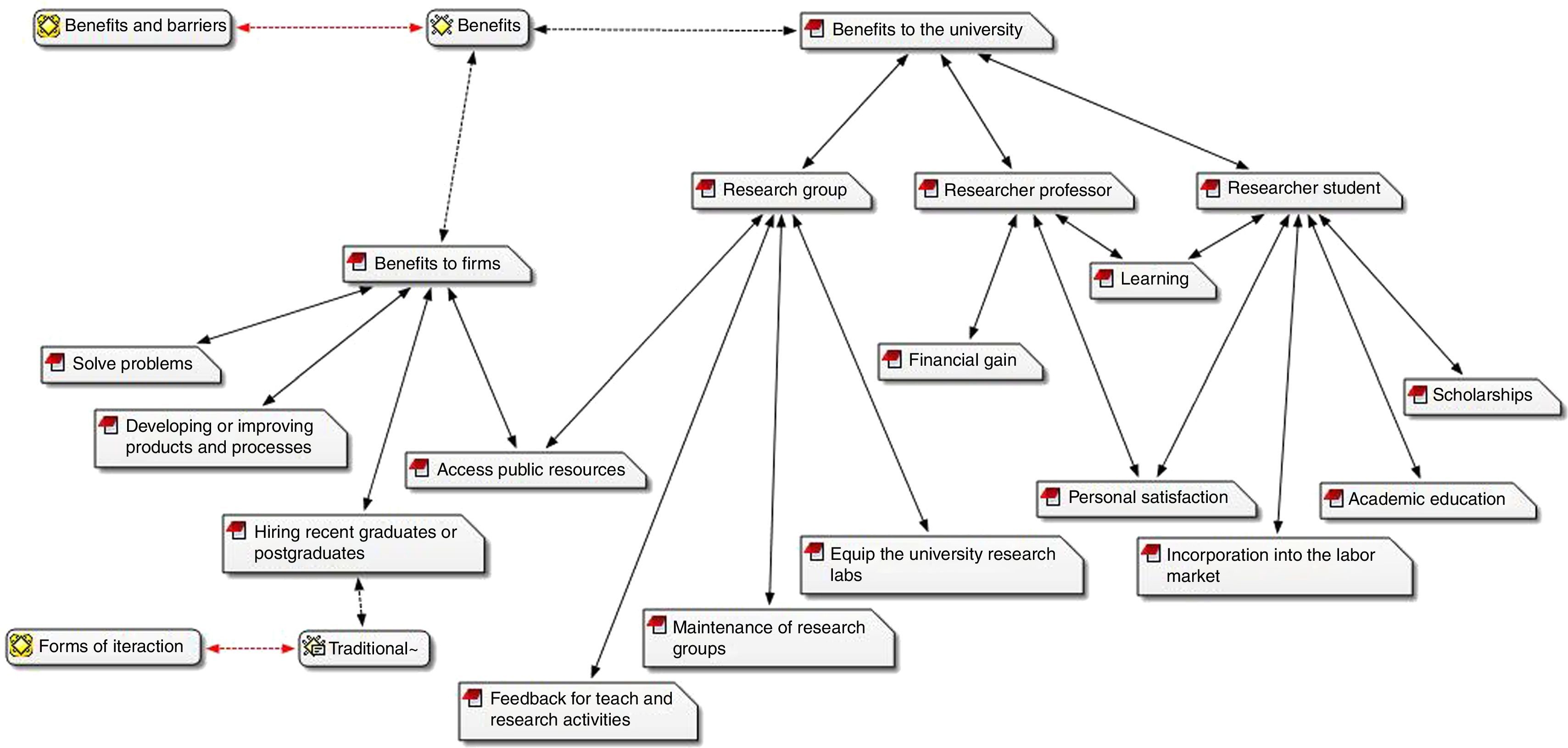

BenefitsThe literature on U–I interaction often questions what each party has to gain from such relationships and seeks to identify what factors affect this process. It is important to discuss these aspects, beginning with the benefits that the process can bring to the firm and university as well as those for research groups and the researcher.

Regarding benefits to firms, the survey indicated an aspect that is not mentioned in the literature but is of great importance in Brazil: the possibility of the firm accessing public resources made available through public policies to promote innovation. This has caused many firms to give more importance to innovation emanating from this area and also awaken the need for joint projects with the university. Researchers have a clear view on the issue, as can be seen: “[Firms] can benefit from hiring research through universities and the resources provided by FINEP. This contributes to innovation and is contributing a lot, because the staff are running behind” (GP6).

In accordance with Bishop et al. (2011), Lee (2000), and Mueller (2006), another benefit that firms have is the possibility of developing or improving products and processes, which can be illustrated by this respondent: “Producers cannot fulfill their function in Brazil if they do not use our technology …Virtually all products of firms have been improved based on the knowledge that we give them” (GP3).

Bishop et al. (2011), Dutrénit and Arza (2010), and Meyer-Kramer and Schmoch (1998) demonstrate that ties with universities help firms to solve problems and facilitate the hiring of qualified personnel, which is part of the traditional channel category.

On the issue of the benefits to the university, it was found that all aspects mentioned by D’este and Perkmann (2011) and Lee (2000) appeared in the comments of respondents. Access to funding, infrastructure, and equipment was the most mentioned issue, along with professor and student learning opportunities and the professional integration of students. Such aspects will be further deepened in relation to the perspective of the researcher and research groups.

It is possible to see commercial benefits with regards to the university as an institution, although it is little noticed by researchers in general. Perhaps this is because commercial activities are still incipient, as previously mentioned.

From the view of the researcher and research groups—and according to that discussed by Arza (2010) and Dutrénit and Arza (2010)—there are economic benefits that include the provision of resources and equipment, as well as intellectual benefits associated with learning, training, and personal satisfaction.

From the point of view of the research group, many researchers said they could equip the university research labs with just the funds from projects developed in collaboration with firms. These resources are important for the maintenance and continuity of research groups as well as the functioning of activities. The statement below reveals this facet: “Thanks to our partnerships, we can significantly improve our infrastructure for teaching, research, and services provision by purchasing equipment that at one time was a utopian dream, but is today a reality” (GP24).

Research groups and firms can benefit from access to public resources through collaboration that would otherwise not be available. A study by Tartari and Breschi (2012) found that the access to financial and non-financial resources is the most important factor for enabling researchers at universities to increase their collaboration with firms.

In addition to economic benefits, there is the explicit recognition by researchers that interaction with industry feeds teaching and research activities. In this sense, results can be gained through projects with firms as well as through participation in research that may inspire new ideas and possibilities in scientific fields.

In the view of the researcher—both students and professors—the economic benefits are also mentioned, but are less apparent than those listed by the research groups. Scholarship opportunities that are specifically linked to projects in partnership with industry are cited in addition to that normally provided by universities. For professors, the possibility of obtaining financial gain is present, but these are to be expected.

The main focus is on intellectual benefits such as learning and student graduation, as well as incorporation into the labor market. Learning opportunities are common to both professors and students: “Being with firms made my student grow and made me grow. Businesspeople help me grow professionally” (GP22).

The development of students and their integration into the labor market are benefits directly related to the learning opportunities that are provided through industry interactions, which are not normally obtained with educational activities in the strict sense. One factor that supplements student development is the possibility of being close to market realities. In this sense, partnerships contribute to lowering the barriers between the academic world and the business world.

Comment is still needed on more intangible benefits; that is, those related to personal satisfaction, the feeling of “mission accomplished”, and social contribution, which are also mentioned by researchers as important aspects of the relationship with firms. This is demonstrated by the following account: “The work is innovative, we will see it in the market itself. When the students see the results, it is one of the most rewarding aspects” (GP6).

Fig. 3 provides a broad conception of the indicated benefits.

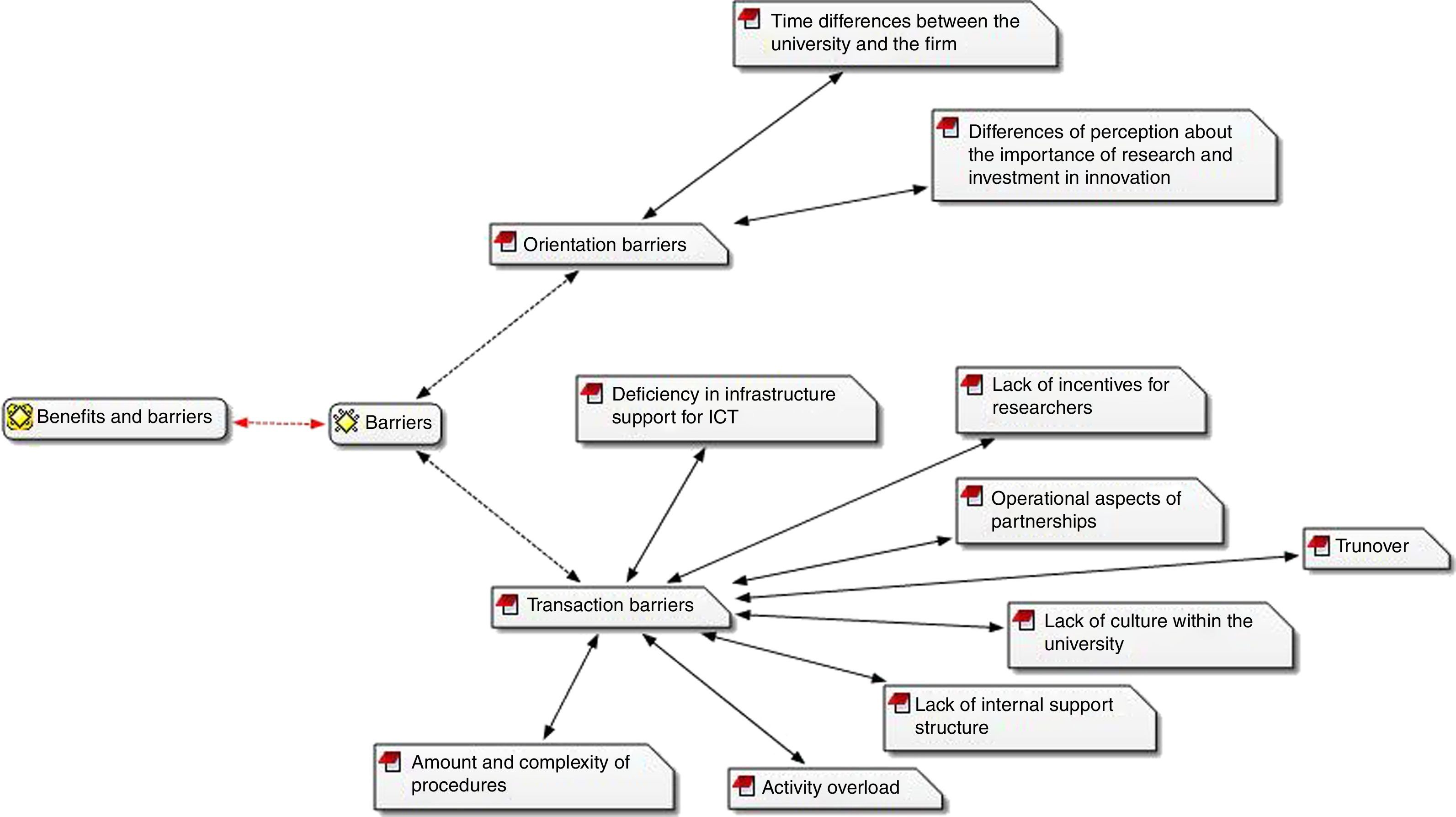

BarriersWith respect to barriers to U–I interaction, an analysis was made that uses the considerations of Bruneel et al. (2010) and Lhuillery and Pfister (2009) as a starting point. They show that there are orientation barriers related to differences in the direction that the university and firm have as institutions and transaction barriers related to the operating mode of the interaction process between the two parties. It was possible to see that orientation barriers are less present in the process compared to more complex transaction barriers, which is discussed below.

One crucial orientation barrier seen in this research is the perception of time differences that exists between the university and the firm; that is, firms are usually more attentive to time, deadlines are shorter, and their processes leaner. The university, in turn, has its own time dynamic that works more in the medium and long term, causing a mismatch between the two. According Bruneel et al. (2010), this is a classic barrier in U–I interaction processes.

With this point, it is important to consider that the orientation of both universities and the firm is related to the context in which each institution works, and that the logic that governs them is different: the firm is focused on the market while the university is concentrated on the production of scientific knowledge. The market demands quick results, which are not in line with the objective of knowledge production that have a cumulative character and are dependent on multiple experiments and testing.

Another related aspect is the perception that researchers have about the importance of research to economic development and the need for investment in innovation, which is often not shared by firms, or demands for concrete action. There are many situations where there is agreement between firms and universities, but firms prioritize immediate survival because innovation is often associated with risk, as illustrated by the following statement: “[T]here is a will and clear understanding of businesspeople with regard to innovation, but sometimes accepting that it involves a financial cost is a little difficult” (GP5).

As for transaction barriers, the main complaint of the researchers lies with the amount and complexity of procedures involved in research activities, especially those related to operational issues of the research group such as purchasing resources and equipment. Researcher burdens in relation to the management of partnership projects are identifiable, which often take ample time and shift focus away from research ends. Another related point is that many researchers have expressed that they are not trained for such activities—a required area of knowledge that they do not have.

A structure within the university to give researchers support in activities peripheral to research projects in conjunction with industry can help this problem, although researchers often do not identify this support. This fact—apparent in the respondents’ view—constitutes a barrier that prevents them from advancing toward the establishment of a continuous relationship.

Another barrier identified by respondents is the issue of lack of culture within the university regarding the establishment of relationships of this nature as well as the lack of understanding of what U–I interaction consists of. The absence of this broader understanding often creates internal resistance, which leads to ideological discussion. It is common for respondents to refer to other countries whose innovation systems are supported by more consistent U–I interactions than Brazil's, thus justifying their positions on the establishment of more concrete and continuous relationships. In this sense, hybrid organizations seem to be a response to this kind of cultural barrier, applicable to all regions that seek technological innovation as an engine for economic development, which can channel knowledge and technological transfer efforts (Davidson & Lamb, 2004).

There are also operational barriers regarding the establishment and continuation of partnerships. Aspects related to contracts, terms for the transfer of technology and intellectual property, as well as the payment of royalties, typically involve extensive negotiations between two parties, especially on legal matters.

Although universities usually work with a long-term view of research, many students are only there for a relatively short period of time, that is, alumni are only part of research groups in the time that they are connected to the university. This feature provides difficulty to the continuity of projects and calls into question the ability of the university to meet firm deadlines. This constitutes a barrier, as demonstrated by one respondent: “The main reason that the university does not give quick responses like firms is that they perhaps wish or need us to work with labor that is changing all the time” (GP8).

Respondents also pointed to the lack of incentives for students and teachers with regards to the establishment of relationships with firms. There is a feeling of discontent in relation to the intensity of academic activities; that is, regardless of the efforts made and the results achieved, the form of financial compensation is the same. For the student, sponsorship money is meager compared to some opportunities in the labor market, and for professors there is no incentive policy that values research or the results obtained in cooperation with firms.

The last of the barriers relates to the infrastructure support for ICT made available to the researcher, where issues of clarity and operational difficulties of certain instruments or ICT programs can be seen. Other issues comprise of the complexity involved in the processes related to such programs and the institutional weakness of public bodies.

Fig. 4 provides a summary of the orientation and transaction barriers.

Final considerationsFor the analysis of U–I interaction in Santa Catarina, evolutionary phases, forms of interaction, and benefits and barriers as categories of analysis were studied. Evolutionary phases were identified in accordance with Plewa et al. (2013). Most of the actions were concentrated in the pre-linkage phase, which, in a way, conditions the development of the U–I interaction as a whole. It is noticed that the respondents exerted much effort in the prospecting of interaction through the establishment of contact networks, and they also had a strong involvement in discussions about the contractual nature of relationships. This behavior occurred because of external stimuli (the government and competitive environments) as well as internal stimulus (the university).

In general, the research showed that there is no linearity in the evolutionary phases of U–I interaction, but it is possible to describe the actions of research groups, which reveal the dynamics of such relationships and how they change over time. Plewa et al. (2013) add that the latent phase can also occur after the pre-linkage or engagement phase, depending on the specific circumstances of each type of relationship.

With regard to the forms of interaction, it can be seen that most of the relationships between universities and firms are concentrated in traditional and services channels, whose interaction takes place in the short term, with knowledge flows going from universities to firms. Interaction initiatives exist in the medium and long term, which implies an intense exchange of knowledge between the parties; however, these were a minority and subject to the historical trajectory of research group interaction. This fact indicates the need for the maturation of research groups in their lines of work as well as firms in their development projects.

This aspect may also be related to what Maculan and Mello (2009) call the proximity to university ethos, that is, making it easier to establish interactions related to activities emanating from teaching, research, and extension. These only represent an expansion of what universities commonly do more than those that require a broader transformation toward acquisition skills that are not traditionally academic, which require commercial and bi-directional channels. The position taken by universities and how prepared their internal structures are in receiving the new activities arising from these traditionally non-academic skills have direct implications. Conclusions related to these considerations were found in the study of Perkmann et al. (2013), realizing that researchers see collaboration as a natural extension of scientific activities, while issues related to commercialization are seen as a separate activity type.

This result also explains the incipient culture for the production of patents in Brazil by universities, when difficulties related to their incorporation in the commercial channel are considered. In this intense environment of institutional pluralism, we must consider the prospect of hybrid organizations that, according to Pache and Santos (2013), look for different elements of institutional logics and their combination with competing logics. The selection and mixing of elements from each of these logics then permits the management of incompatibilities and thus reduces the risks and costs of strategies.

On the issue of benefits and barriers, the research results extend the avenues outlined in the literature (Bishop et al., 2011; Bruneel et al., 2010; D’este & Perkmann, 2011; Dutrénit & Arza, 2010; Lee, 2000; Lhuillery & Pfister, 2009; Meyer-Kramer & Schmoch, 1998; Mueller, 2006). To an extent, these characteristics were seen in the interactions in Brazil, whose relationships are still new and have a solid trajectory yet to be built.

There was no reference in the literature to the benefits pointed out by researchers related to the possibility of accessing public resources in order to subsidize innovation. In this sense, public policies for fostering ICT in the country, reinforced by the regulatory framework in the field of innovation, have proven to be effective for the development and consolidation of U–I partnerships. Thus, it was identified that the main motivation for the realization of some joint projects was the ability to access public resources that require some form of collaboration.

It is emphasized that research group access to public resources has a common benefit for firms and universities. Regarding the benefits for researchers, it was found that learning and personal satisfaction are commonalities. It is also possible to see that hiring recent graduates or postgraduates figure as a traditional channel of interaction and as a benefit to universities. A greater range of benefits for universities compared to firms was also identified, a result that may have been influenced by the origins of the research, since all were linked to universities.

The main limitation of this study is the analysis of the U–I interaction phenomenon from the perspective of the university, that is, there was no data analyzes from the firm end of the studied interaction. The fact that it is a regional study should also be considered as other areas could have similarities, or result complementarities could have been reached.

With regards to barriers, transaction barriers linked to operational aspects of interactions, including cultural and administrative issues, were particularly prevalent. It should also be noted the a small number of orientation barriers in relation to transaction barriers means that, in most cases, operational or ideological aspects are not hindering relationships with industry. It is important to be aware of the gains that can come from U–I interaction as well as to ponder the barriers that effectively make this relationship work in a continuous form.

On the avenues for future studies, it is understood that this research uncovers several issues that deserve more attention. The issue of the impact of public resources in joint U–I projects and research group longevity verses the success of partnerships are crucial, particularly when investigating issues such as the turnover of the group members, relationship forms, and management.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Departamento de Administração, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo – FEA/USP.