To identify predictors of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among former athletes.

MethodThis cross-sectional study included 186 subjects (64% male, aged 40–64 years), representing 51.4% of former athletes from the Jogos Abertos de Santa Catarina (1960–2006). The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) was used to assess HRQoL (Physical Health and Mental Health summary scores). Sociodemographic variables (gender, age, education, occupation, marital status and income), health status (body mass index, medication use, chronic problems, sports injuries that affect current daily living and health guidance from their coaches), time since they stopped competing and leisure-time physical activity were exploratory variables. Multivariate linear regression models were used.

ResultsSports injuries that affect current daily living (standardised score [β]=−0.430 and −0.133), body mass index (β=−0.226 and −0.238) and chronic problems (β=−0.138 and −0.144) were predictors of both Physical Health and Mental Health. Prescription medicine (β=−0.177) and occupation (β=0.095) predicted only Physical Health scores, and income (β=0.224) predicted only Mental Health scores (all p<0.05).

ConclusionThese variables can be focused on HRQoL promotion strategies among former athletes.

Identificar predictores de calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) en exatletas.

MétodoEste estudio transversal incluyó 186 sujetos (64% hombres, con edades entre 40-64 años), lo que representa el 51.4% de los exatletas de los Jogos Abertos de Santa Catarina (1960-2006). El Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) se utilizó para evaluar la CVRS. Las variables sociodemográficas (sexo, edad, educación, ocupación, estado civil e ingresos económicos), el estado de salud (índice de masa corporal, uso de medicamentos, problemas crónicos, lesiones deportivas que afectan a la vida diaria actual y la orientación hacia la de salud de sus entrenadores), el tiempo desde que dejaron de competir y la actividad física en el tiempo libre fueron las variables exploratorias. Se utilizaron modelos de regresión lineal multivariante.

ResultadosLas lesiones deportivas que afectan a la vida diaria actual (standardised score [β]=–0.430 y –0.133), el Índice de Masa Corporal (β=–0.226 y –0.238) y los problemas crónicos (β=–0.138 y –0.144) fueron predictores tanto de la salud física como de la salud mental. El uso de medicamentos (β=–0.177) y la ocupación (β=0.095) predijeron sólo las puntuaciones de salud física, y los ingresos (β=0.224) predijeron sólo las puntuaciones de salud mental (todas las p<0.05).

ConclusiónEstas variables pueden ser focos importantes para las estrategias de promoción de la CVRS en los exatletas.

Identificar os preditores da qualidade de vida relacionada à saúde (QVRS) em ex-atletas.

MétodoEstudo transversal que incluiu 186 indivíduos (64% de homens, idades de 40-64 anos), representando 51.4% dos ex-atletas medalhistas do atletismo nos Jogos Abertos de Santa Catarina (1960-2006). O instrumento Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) foi utilizado para mensurar a QVRS (sumários saúde física e saúde mental). Variáveis sociodemográficas (sexo, idade, educação, ocupação, estado civil e renda), estado de saúde (índice de massa corporal [IMC], uso de medicamentos, doenças crônicas, lesões esportivas que atrapalham o cotidiano atual e orientações de saúde pelos treinadores), o tempo aposentado de competições e atividade física no lazer foram variáveis exploratórias. A regressão linear multivariada foi utilizada.

ResultadosLesões esportivas que atrapalham o cotidiano (escore padronizado [β]=–0.430 e –0.133), índice de massa corporal (β=–0.226 e –0.238) e doenças crônicas (β=–0.138 e –0.144) foram preditores da saúde física e saúde mental. Medicamentos prescritos (β=–0.177) e ocupação (β=0.095) predisseram a saúde física, enquanto que renda (β=0.224) foi preditor da saúde mental (p<0.05).

ConclusãoEssas variáveis podem ser focadas na promoção de QVRS em ex-atletas.

Research in Sport Science has been focused on former athletes, especially to understand how these individuals are affected (i.e., their metabolic health, fitness and quality of life [QoL]) when the sports career is or has come to an end.1,2 In general, former athletes tend to partake harmful health process more than active athletes, including having increased fat-mass,3 reduced performance,3,4 risky behaviours (e.g., unhealthy eating)7 and poor mental health (e.g., risk of anxiety/depression).5,6 Economic and social problems have also been found in former athletes including their difficulty in finding work and maintaining income,6 low social support and low social activities.5 However, in comparison to the general population, former athletes have shown better health factors (e.g., health behaviours and cardiovascular health),2,7–9 lower risk of depression/anxiety8,9 and better health-related QoL (HRQoL).10

HRQoL involves evaluating the behavioural functioning, subjective well-being, and perceptions of overall health to determine the physical and mental status of each person: it is usually measured by instruments such as the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).11,12 Measuring HRQoL can help determine the burden of preventable diseases, injuries and disabilities, especially in middle and old ages.11 In particular, HRQoL assessment among former athletes may be important in order to measure the health benefits of sports participation and whether these outweigh the risks.1 Additionally, it is important to identify whether post-sports life conditions (e.g., chronic injuries, lifestyle and socioeconomic conditions) have an impact on physical and mental aspects.1,13

Studies were conducted with former athletes in order to identify psychological aspects such as depression/anxiety,5,9,14 self-rated health,8 perception of physical limitations15,16 and life satisfaction.13 However, the specific aspects of HRQoL (i.e., Physical Health and Mental Health measured with the SF-36) in a sample of former athletes are still unknown.

Studies on predictors (i.e., factors that can explain the outcome) of the psychological aspects among former athletes included sociodemographic factors (e.g., age, income, education)8,9,13 and health conditions (e.g., chronic problems, physical activity).5,8,9,15 Among the clinical conditions, injuries during the sporting career have been shown to be negatively associated with QoL17 and HRQoL18 among adult active athletes, and the symptoms of depression/anxiety5 and aggression14 among former athletes. However, the predictive power of former athletes’ HRQoL from demographic, economic and health conditions is something that needs clarification. A study that fills these gaps can indicate the main variables (at different levels, from the demographic to behavioural aspects) to be focused in health and QoL promotion among former athletes. This will contribute to more effective interventions among professionals (i.e., coaches, Performance and Health professionals, Physiotherapists) and people involved with athletes who are close to or already done with their sports careers.

Thus, this study aimed to verify whether sociodemographic factors (gender, age, education, occupation, marital status and income), medical and health conditions (body mass index [BMI], medicine use, chronic problems, sports injuries that affect current daily living, time since they stopped competing and health guidance from their coaches) and leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) are predictors of HRQoL (Physical Health and Mental Health summary scores) among middle-aged former athletes.

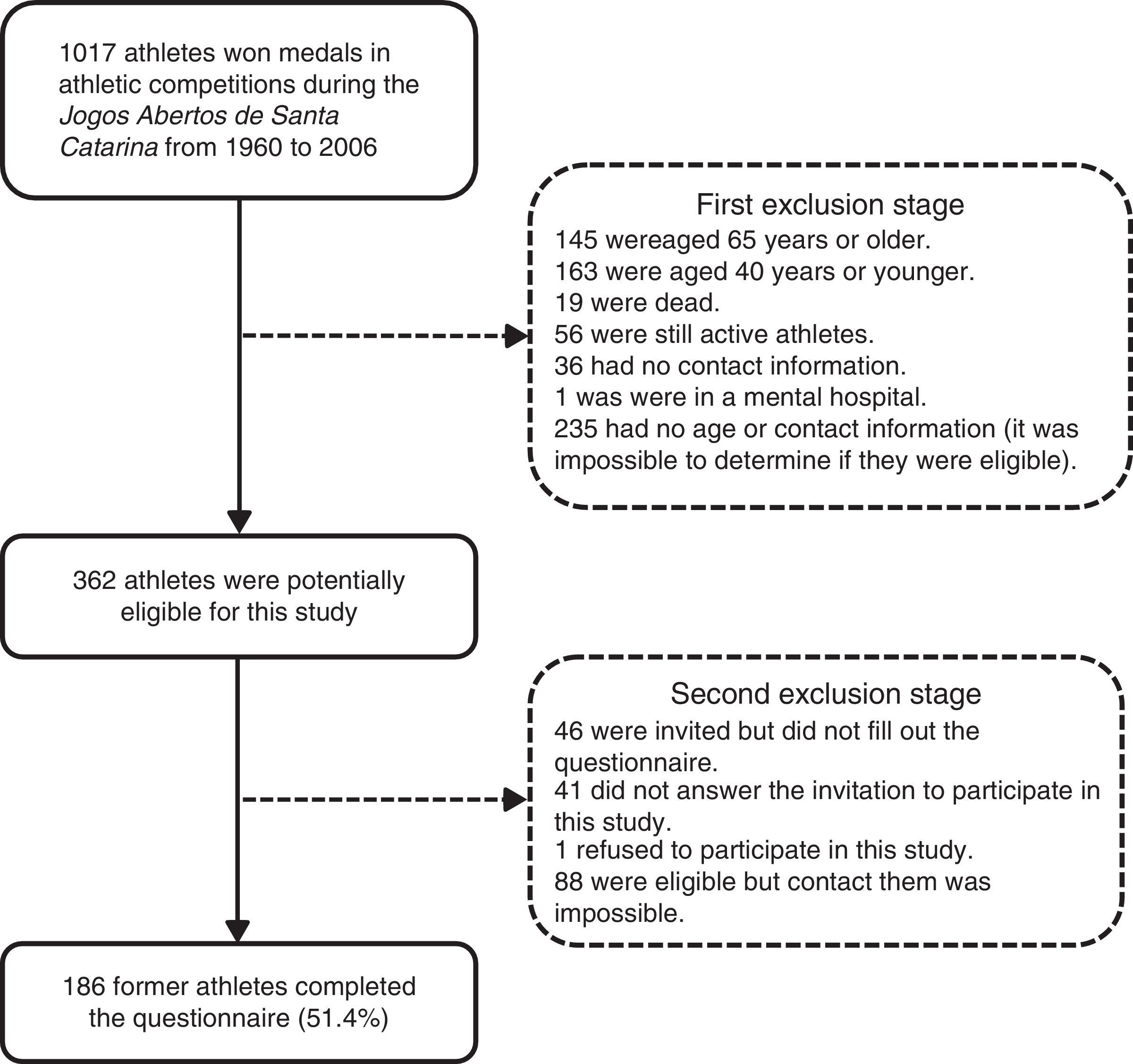

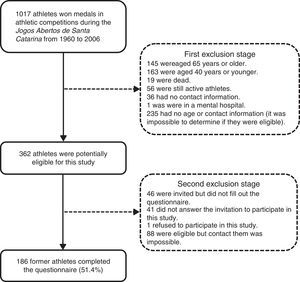

MethodSubjectsThis was a cross-sectional study. The process of defining the study population and sample selection is detailed in Fig. 1. The study population involved former athletes who participated in the Jogos Abertos de Santa Catarina (JASC) and were medallists in at least one of the individual and collective modes of athletics. The Jogos Abertos (Open Games in Portuguese) occur annually in several Brazilian states and represent the largest multisport competition in the state of Santa Catarina, southern Brazil. The athletics games have been included in JASC since its first edition in 1960. The athletics games were chosen because there is a medallist record, which would allow for the determination of and contact with the population of interest to the study. The study population included the medallists from the JASC's 1st edition in 1960 to the 47th edition in 2006. In this period, 1017 athletes won medals in the athletics games.

A list of the medallists was obtained from the Santa Catarina Sports Foundation website (www.fesporte.sc.gov.br), the Municipal Sports Foundation and the Athletics Federation of Santa Catarina. Individuals were eligible (inclusion criteria) for this study if they: (1) won at least one medal (1st, 2nd, or 3rd place) in the JASC; (2) had personal data (e.g., home address, or telephone number) to available so they could be contacted and invited; (3) ended their sports career five or more years before the study (i.e., in 2006 or before); and (4) were aged from 40 to 64.9 years.

A total of 362 former athletes were considered eligible for the study. All former athletes were thoroughly invited to participate in this study, through personal, telephone and/or electronic contacts. A minimum of four contact attempts were carried out for each individual. In the end, 186 former athletes agreed to participate and they effectively answered the questionnaire (51.4% of those who were eligible, exclusion reasons in Fig. 1). This sample included former athletes who resided in 31 municipalities from Santa Catarina and eight other different states in Brazil.

The calculation of the sample's statistical power was carried out a posteriori using the G*Power v.3.0 software. The sample of 186 former athletes identified prediction percentages of 34.4% and 13.5% of the variation of scores of Physical Health and Mental Health, with a statistical power greater than 90% (α=0.05). Additionally, this study had a ratio between the number of participants and predictor variables higher than 10:1.

The study's procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (protocol no. 167 678). Before answering the questionnaire, former athletes were informed of the objectives, methods of collection, the voluntary nature of participation and guarantee of confidentiality of individual responses. The participants signed the consent form.

Experimental proceduresThe SF-36 questionnaire was used to assess HRQoL. This instrument was translated and validated previously and it had adequate proprieties to assess HRQoL in the Brazilian population.19 SF-36 considers the last four weeks of the respondent's life and includes 36 items that are grouped into eight dimensions (functional capacity, physical aspects, pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional and mental health) of the individual's health status. The scores for each dimension were converted to a scale from 0 (worst health status for that dimension) to 100 (best health).12 This instrument also allowed the grouping of HRQoL aspects into two summary scores: Physical Health and Mental Health.

Different variables were studied as potential predictors of HRQoL (Physical Health and Mental Health summary scores) among former athletes. The questionnaire included items on gender (male; female), age groups (40–49; 50–59; 60–64.9 years), education (up to completed high school; college or higher education) occupational status (still working; retired/never worked), income (up to 6 minimum wages; 6–9 minimum wages; 10+ minimum wages) and marital status (living without a partner; married/living with partner). These items considered the questionnaire from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.20

Some health variables were studied. Weight and height were self-reported and BMI (weight/height2) was calculated and classified according to international criteria for normal weight (BMI<25.0kg/m2), overweight (BMI between 25.0 and 29.9kg/m2) and obesity (BMI≥30.0kg/m2) in adults.21 Other questions were structured to assess the regular use of prescription (no; yes) and non-prescription medicines (no; yes), self-reported chronic problems (no; yes), sports injuries that affect current daily living (e.g., bathing, sleeping or walking: no; yes), time since they stopped competing (5–10 years; 11–15 years; over 15 years), and health guidance from their coaches (no; yes). The questions were based on an instrument previously used with the Brazilian population.22

LTPA was assessed using the leisure-time domain from the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) long version.23 This domain assesses the frequency and duration (which allows us to calculate the weekly volume) of walking, and moderate and vigorous LTPA during the week prior to the survey. The weekly time of each LTPA type was calculated by multiplying the weekly frequency by the daily duration for each LTPA type.

Data collection was conducted from September to November 2012. Data were collected through a self-administered questionnaire, that was sent to respondents as an electronic or printed document. The completion of the questionnaires, when necessary, was accompanied online or in person by the researchers to clarify any questions that arose during the filling-out process.

Statistical analysisMean values, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum values were used for continuous variables. The absolute and relative frequency was used to describe categorical variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to identify the distribution of the data (parametric or non-parametric). The transformation of logarithmic data was used for the variables that did not present parametric distributions (weekly LTPA time and HRQoL summaries).

Linear regression models were used in order to verify the potential predictors of two HRQoL summaries (Physical Health and Mental Health) among former athletes. The sociodemographic variables (gender, age, education, occupation, marital status and income), health status (nutritional status, use of prescription and non-prescription drugs, chronic problems, sports injuries, time since they stopped competing, and health guidance from their coaches) and the weekly time of LTPA were considered independent variables. The bivariate association was tested between each variable and HRQoL summaries. Multivariate regression models analysed the association between each variable and HRQoL summaries, controlling the presence of other variables in the same model. The inclusion of variables in the model was performed in forward mode. Standardised scores (β), predictive values (R2) and p-values are presented for each variable included in the raw and adjusted regression models.

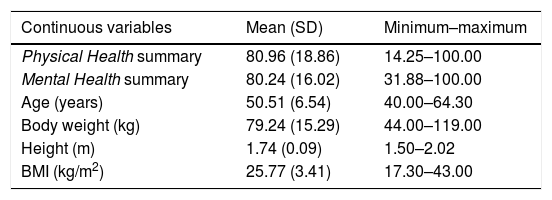

ResultsThe final sample consisted of 186 former athletes aged 40–64 years (mean=50.51 years, SD=6.54 years). The sample had a higher participation of male former athletes (64.0%) and who had ended their sports careers over 15 years ago (60.2%). Most of them reported that they were still working (84.4%), had completed their college education (86.0%), were married (75.8%) and earned up to six minimum-wages (36.6%, Table 1).

Characteristics of the former athletes included in this study (n=186).

| Continuous variables | Mean (SD) | Minimum–maximum |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Health summary | 80.96 (18.86) | 14.25–100.00 |

| Mental Health summary | 80.24 (16.02) | 31.88–100.00 |

| Age (years) | 50.51 (6.54) | 40.00–64.30 |

| Body weight (kg) | 79.24 (15.29) | 44.00–119.00 |

| Height (m) | 1.74 (0.09) | 1.50–2.02 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.77 (3.41) | 17.30–43.00 |

| Categorical variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 119 | 64.0 |

| Female | 67 | 36.0 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Still working | 157 | 84.4 |

| Did not working/retired | 29 | 15.6 |

| Education | ||

| Up to completed high school | 26 | 14.0 |

| Completed college school | 160 | 86.0 |

| Income | ||

| Up to 6 minimum-wages | 68 | 36.6 |

| 6–9 minimum-wages | 51 | 27.4 |

| 10 or more minimum-wages | 67 | 36.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Living without a partner | 45 | 24.2 |

| Married/living with partner | 141 | 75.8 |

| BMI status | ||

| Normal weight (<25.0kg/m2) | 79 | 42.5 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9kg/m2) | 90 | 48.4 |

| Obesity (≥30.0kg/m2) | 17 | 9.1 |

| Use of prescription medicine | ||

| No | 123 | 66.1 |

| Yes | 63 | 33.9 |

| Use of non-prescription medicine | ||

| No | 157 | 84.4 |

| Yes | 29 | 15.6 |

| Chronic problems | ||

| No | 128 | 68.8 |

| Yes | 58 | 31.2 |

| Sports injuries that affect current daily living | ||

| No | 150 | 80.6 |

| Yes | 36 | 19.4 |

| Time since they stopped competing | ||

| 5–10 years | 49 | 26.3 |

| 11–15 years | 25 | 13.4 |

| Over 15 years | 112 | 60.2 |

| Health guidance from their coaches | ||

| No | 106 | 57.0 |

| Yes | 80 | 43.0 |

BMI: body mass index; SD: standard deviation.

Considering clinical and health conditions, most former athletes were overweight (48.4%) and reported that they did not have chronic problems (68.8%) and were not using prescribed (66.1%) or non-prescribed (84.4%) medicines. Two out of ten (19.4%) former athletes reported that sports career injuries affected their current daily living. Most former athletes reported that they did not receive health guidance from the person who coached them during their sports career (57.0%, Table 1).

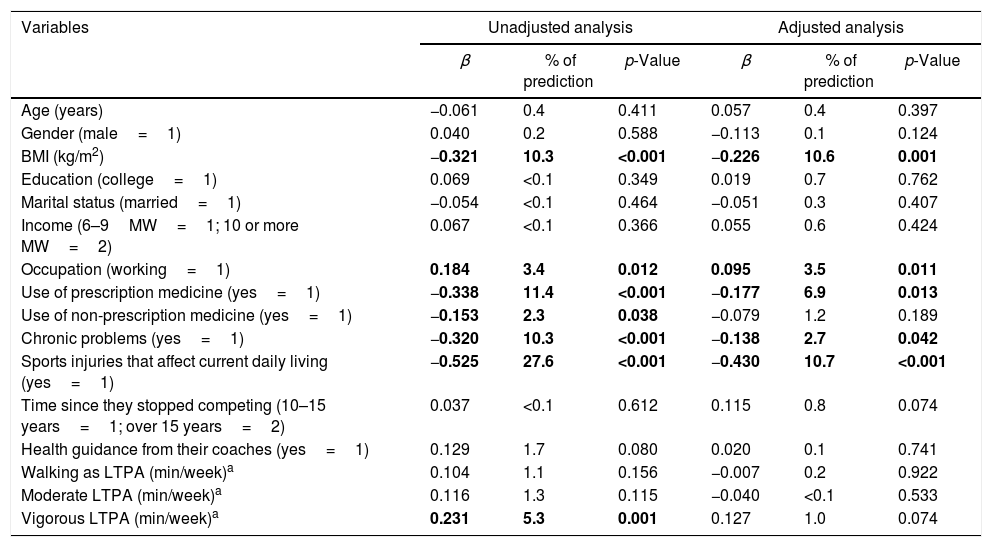

In the crude regression analysis, occupation and vigorous LTPA were positively and significantly associated with Physical Health. BMI, use of prescription medicine, use of non-prescription medicine, chronic problems and sports injuries that affect current daily living were negatively associated with Physical Health (Table 2).

Standardised coefficient score (β), predictive value (R2 in percentage) and statistical significance for crude and adjusted analyses between Physical Healtha and predictor variables.

| Variables | Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | % of prediction | p-Value | β | % of prediction | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | −0.061 | 0.4 | 0.411 | 0.057 | 0.4 | 0.397 |

| Gender (male=1) | 0.040 | 0.2 | 0.588 | −0.113 | 0.1 | 0.124 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.321 | 10.3 | <0.001 | −0.226 | 10.6 | 0.001 |

| Education (college=1) | 0.069 | <0.1 | 0.349 | 0.019 | 0.7 | 0.762 |

| Marital status (married=1) | −0.054 | <0.1 | 0.464 | −0.051 | 0.3 | 0.407 |

| Income (6–9MW=1; 10 or more MW=2) | 0.067 | <0.1 | 0.366 | 0.055 | 0.6 | 0.424 |

| Occupation (working=1) | 0.184 | 3.4 | 0.012 | 0.095 | 3.5 | 0.011 |

| Use of prescription medicine (yes=1) | −0.338 | 11.4 | <0.001 | −0.177 | 6.9 | 0.013 |

| Use of non-prescription medicine (yes=1) | −0.153 | 2.3 | 0.038 | −0.079 | 1.2 | 0.189 |

| Chronic problems (yes=1) | −0.320 | 10.3 | <0.001 | −0.138 | 2.7 | 0.042 |

| Sports injuries that affect current daily living (yes=1) | −0.525 | 27.6 | <0.001 | −0.430 | 10.7 | <0.001 |

| Time since they stopped competing (10–15 years=1; over 15 years=2) | 0.037 | <0.1 | 0.612 | 0.115 | 0.8 | 0.074 |

| Health guidance from their coaches (yes=1) | 0.129 | 1.7 | 0.080 | 0.020 | 0.1 | 0.741 |

| Walking as LTPA (min/week)a | 0.104 | 1.1 | 0.156 | −0.007 | 0.2 | 0.922 |

| Moderate LTPA (min/week)a | 0.116 | 1.3 | 0.115 | −0.040 | <0.1 | 0.533 |

| Vigorous LTPA (min/week)a | 0.231 | 5.3 | 0.001 | 0.127 | 1.0 | 0.074 |

BMI; body mass index; LTPA: leisure-time physical activity; MW: minimum-wages.

Bold values were statistically significant (p<0.05).

After adjustment for confounders, the variables that remained significantly associated with Physical Health were occupation, BMI, use of prescription medicine, chronic problems and sports injuries that affect current daily living. These variables predicted 34.4% of the variation in the Physical Health scores among former athletes. The variables with the largest association with Physical Health were BMI (β=−0.226; R2=−0.106) and sports injuries that affect current daily living (β=−0.430; R2=−0.107). The use of non-prescription medicine (p=0.189), the time since they stopped competing (p=0.074) and vigorous PA (p=0.074) lost association with Physical Health after adjusting for other independent variables (Table 2).

In the crude analysis, income and vigorous LTPA were positively and significantly associated with Mental Health. BMI, use of prescription medicine, chronic problems and sports injuries that affect current daily living were negatively associated will Mental Health (Table 3).

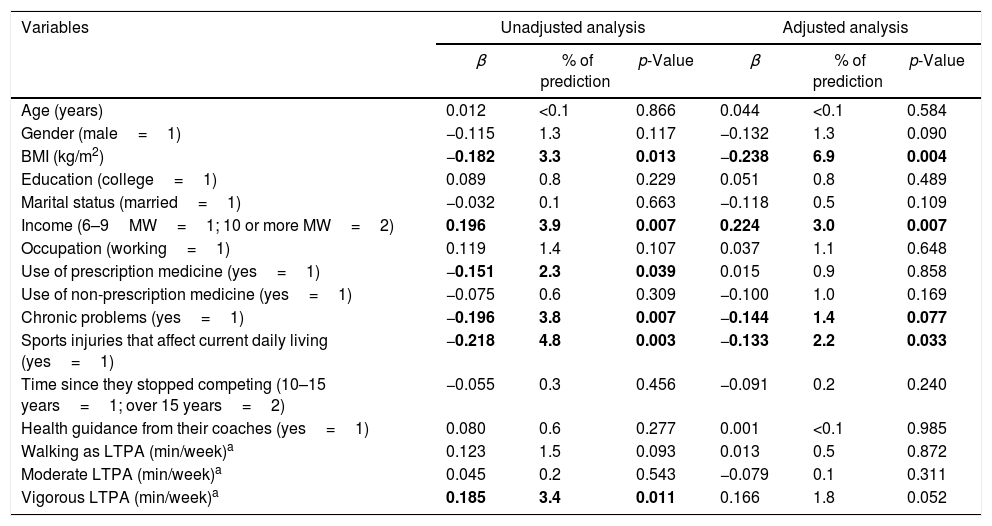

Standardised coefficient score (β), predictive value (R2 in percentage) and statistical significance for crude and adjusted analyses between Mental Healtha and predictor variables.

| Variables | Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | % of prediction | p-Value | β | % of prediction | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 0.012 | <0.1 | 0.866 | 0.044 | <0.1 | 0.584 |

| Gender (male=1) | −0.115 | 1.3 | 0.117 | −0.132 | 1.3 | 0.090 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.182 | 3.3 | 0.013 | −0.238 | 6.9 | 0.004 |

| Education (college=1) | 0.089 | 0.8 | 0.229 | 0.051 | 0.8 | 0.489 |

| Marital status (married=1) | −0.032 | 0.1 | 0.663 | −0.118 | 0.5 | 0.109 |

| Income (6–9MW=1; 10 or more MW=2) | 0.196 | 3.9 | 0.007 | 0.224 | 3.0 | 0.007 |

| Occupation (working=1) | 0.119 | 1.4 | 0.107 | 0.037 | 1.1 | 0.648 |

| Use of prescription medicine (yes=1) | −0.151 | 2.3 | 0.039 | 0.015 | 0.9 | 0.858 |

| Use of non-prescription medicine (yes=1) | −0.075 | 0.6 | 0.309 | −0.100 | 1.0 | 0.169 |

| Chronic problems (yes=1) | −0.196 | 3.8 | 0.007 | −0.144 | 1.4 | 0.077 |

| Sports injuries that affect current daily living (yes=1) | −0.218 | 4.8 | 0.003 | −0.133 | 2.2 | 0.033 |

| Time since they stopped competing (10–15 years=1; over 15 years=2) | −0.055 | 0.3 | 0.456 | −0.091 | 0.2 | 0.240 |

| Health guidance from their coaches (yes=1) | 0.080 | 0.6 | 0.277 | 0.001 | <0.1 | 0.985 |

| Walking as LTPA (min/week)a | 0.123 | 1.5 | 0.093 | 0.013 | 0.5 | 0.872 |

| Moderate LTPA (min/week)a | 0.045 | 0.2 | 0.543 | −0.079 | 0.1 | 0.311 |

| Vigorous LTPA (min/week)a | 0.185 | 3.4 | 0.011 | 0.166 | 1.8 | 0.052 |

BMI: body mass index; LTPA: leisure-time physical activity; MW: minimum-wages.

Bold values were statistically significant (p<0.05).

In the adjusted analysis, BMI, income, chronic problems and sports injuries that affect current daily living remained significantly associated with Mental Health (all p<0.05). These variables predicted 13.5% of the variation in the Mental Health scores among former athletes. The variables with the largest association with Mental Health were BMI (β=−0.238; R2=0.069) and income (β=0.224; R2=0.030). The use of non-prescription medicine (p=0.169), marital status (p=0.109) and vigorous LTPA (p=0.052) lost significant association with Mental Health after adjusting for confounders (Table 3).

DiscussionThis study found that BMI, sports injuries that affect current daily living and chronic problems were significant predictors of Physical Fitness and Mental Health scores among former athletes. Economic factors such as employment and income were also predictors of HRQoL summaries (Physical Fitness and Mental Health, respectively. These variables predicted more than 30% of the variation in scores of Physical Health, and 13.5% of the Mental Health scores among former athletes. Thus, this evidence indicates that studied variables tended to have better predictive power of the physical aspects of HRQoL, while the variables had a discreet precision power (but still were statistically significant) for the mental aspects of HRQoL.

Employment and income were significant predictors of Physical Health and Mental Health, respectively. Similar results were observed for self-rated health8 and depression/anxiety16 in two studies with a mixed sample of former athletes and the general population. It is plausible to think that the motor requirements that occur in the workplace (e.g., crafts, concentration activities, and others) are important for a better understanding of functionality between former athletes.8 Additionally, ensuring a regular income appears to provide opportunities for better environmental conditions (e.g., better housing) and involvement in social activities (e.g., conversations, social gatherings) which are important for mental health.8,9,22

Agresta et al.6 studied Brazilian former football players and found that 59.6% had low-income levels and 41.1% had to receive financial help from family members; just only a few received help from clubs that they represented during their sports careers. In this study, approximately four out of ten former athletes earned up to six minimum-wages. These results support the importance of planning for the financial and professional futures of athletes in order to having create economic conditions and subsequent HRQoL after the end of their sports careers.

BMI had the most predictive power of HRQoL among former athletes. This result is similar to the findings of Jurakic et al.24 in a study of Croatian non-athlete adults. Differently, Backmand et al.8 found no association between BMI and self-rated health among former older athletes. However, studies on BMI and HRQoL among former athletes were not found. The intense routine of eating control and exercise during a sports career can do that athletes are less dedicated to nutritional and body weight control after they ended the competitive period.5 This supposition can explain the finding that almost 50% of this study's sample was overweight. Thus, programmes that emphasise the individual's need to remain active while maintaining eating habits, and how these can strongly contribute to HRQoL among former athletes.

The presence of chronic problems (Physical Health and Mental Health) and the use of prescription medicine (Physical Health) were associated with HRQoL summaries. Similar results were obtained in older adults,22 but there is no study that examined the association between these variables in former athletes. Special attention should be given to former athletes who have chronic problems and use medications frequently. Promoting healthy lifestyles during and after sports careers is important because chronic diseases (including high blood pressure which was the most frequently mentioned disease in this sample) during adulthood are strongly determined by risk behaviour.

Sports injuries that affect current daily living were another variable strongly associated with both Physical Health and Mental Health among former athletes. Gouttebarge et al.5 did not find a significant association between multiple lesions and symptoms of depression/anxiety in former professional football players from six countries. No study evaluated the predictive power of HRQoL from sports injuries, which represents a relevant aspect of this study.

This study did not find a significant association between LTPA and HRQoL summaries. A systematic review indicated a positive and strong association between PA and QoL among older adults, but this association can vary according to QoL aspects or PA domains.25 Backmand et al.16 found a positive and longitudinal association between PA and perceived functional capacity among former older athletes who only participated in team sports, but not in other sports (i.e., individual sports, fighting). Backmand et al.8 also showed a positive association between PA and self-rated health among former athletes.

Vigorous LTPA had a non-significant trend (p-value of 0.074 and 0.052 for Physical Health and Mental Health, respectively) for predicting the HRQoL scores. Probably, these results indicate that former athletes need high-intensity PA in order to achieve the benefits in HRQoL. However, this topic has few studies and still needs to be discussed and tested in the literature, especially in studies with designs that ensure temporality control (i.e., longitudinal studies).

Practical implications for professionals involved with athletes were obtained with these results. Appropriate energy balance, especially through regular PA and healthy eating can be a key element in achieving a healthy body weight, as well as the prevention of chronic conditions. Economic and occupational support for former athletes is needed to guarantee higher HRQoL perception in this population. In addition, professionals should pay attention to the prevention of sports injuries among athletes, because the impact of injuries on momentary limitations is obvious, but also, they can negatively and strongly affect future HRQoL aspects (Physical Health and Mental Health). Athletes who are close to sports retirement and former athletes can receive interventions to improve functional capacity and social and emotional involvement in order to contribute to a better HRQoL among people who have sports injuries.

Some strong points of this study should be highlighted. First, HRQoL among former athletes which is something that deserves a special attention,1 especially when different constructs of HRQoL (i.e., Physical Health and Mental Health) were considered. Second, the sample included former athletes from 31 municipalities in eight different states in Brazil. Third, the amount and extension of variables, including demographic, economic, health conditions, and LTPA allowed a strong and significant predictive power of HRQoL summaries among former athletes.

The present study also had limitations. The response rate was approximately 50% and may have reduced the participation of former athletes with lower economic or health conditions. However, this response rate is common in studies that used electronic and printed mail for data collection.14 Another limitation was the use of self-reported information (e.g., HRQoL, LTPA, weight and height), which may explain the lack of association between LTPA and HRQoL summaries. Considering the difficulties of objectively-measured PA in studies with samples from different locations, using validated instruments, such as the IPAQ and SF-36, was viable and acceptable. This study assessed only LTPA and, although this is one of the most important PA domains among Brazilian adults23 and it can greatly predict some health conditions,24 other PA domains (e.g., occupation-time PA) could show different results. Finally, the sample of medallists from a specific competition and sport makes extrapolating the results to other former athletic groups (e.g., non-medallists and other sports) impossible. These limitations do not reduce the importance of this study, but suggest caution in extrapolating the results to other populations and reinforces the importance of other studies focused on HRQoL among this population.

In conclusion, economic factors (employment and income) and clinical and health conditions (IMC, sports injuries that affect current daily living, chronic problems and use of prescription medicine) were significant predictors of HRQoL aspects among former athletes. However, the set of variables had a higher predictive power for Physical Health summary than for Mental Health summary of HRQoL.

Funding sourceThis study had no funding. Individual grants from CAPES to VCBF (protocol number: 10737/14-6).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank the Fundação Catarinense de Esportes, Federação Catarinense de Atletismo and Fundação Municipal de Desportos de Blumenau for allowing us access to data from the Jogos Abertos de Santa Catarina. We thank all former athletes who participated in this survey.