The aim of this report is to describe a rare case of necrotizing pneumonia due to group B Streptococcus serotype III in a relatively young male adult (48 years old) suffering from diabetes. The organism was isolated from his pleural fluid and was only resistant to tetracycline. The patient first received ceftazidime (2g/8h i.v.)+clindamycin (300mg/8h) for 18 days and then he was discharged home and orally treated with amoxicillin clavulanic acid (1g/12h) for 23 days with an uneventful evolution. As in the cases of invasive infection by Streptococcus pyogenes, clindamycin could prevent streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

El objetivo de esta presentación es describir un caso raro de neumonía necrosante debida a estreptococo del grupo B serotipo iii en un diabético adulto de sexo masculino relativamente joven (48 años). El microorganismo fue aislado de líquido pleural y resultó ser resistente solo a tetraciclina. El paciente recibió ceftacidima (2g/8h iv)+clindamicina (300mg/8h) durante 18 días y luego fue dado de alta, bajo tratamiento oral con amoxicilina-ácido clavulánico (1g/12h). Este tratamiento se mantuvo durante 23 días, con buena evolución. Como en casos de infecciones invasivas por Streptococcus pyogenes, es posible que la clindamicina haya evitado la aparición del síndrome de shock tóxico estreptocócico.

Group B streptococcal (GBS) invasive diseases have significantly increased during the past two decades among nonpregnant adults, especially among those with underlying medical conditions or advanced age8. Most cases of invasive GBS disease occur among elderly non-pregnant adults, with a case-fatality rate greater than 10%, exceeding that in infants (3–5%). Approximately one-half of the deaths from invasive GBS disease in the United States occur among adults 65 years of age2,5,7.

Pneumonia due to GBS is most often encountered in elderly people rather than in younger adults. Diabetes mellitus is a risk factor for developing GBS infections as a whole6. The aim of this report is to describe a case of necrotizing pneumonia due to GBS in a young male adult (<65 years of age) suffering from diabetes.

A 48-years-old man with dyspnea (functional class IV), night sweats, nonproductive cough, fever (39°C), and weight loss was admitted to the emergency room of a hospital in La Plata City. He was referred to our hospital for surgical evaluation.

The patient had been suffering from a right-side back pain for over a month. Blood pressure was 110/80mmHg, his heart rate was 120/min, and respiratory frequency was 36/min. Serum potassium level was 4.1mEq/dl. WBC count was 17700/mm3, and plasma glucose was 254mg/dl. A previously unknown type 2 diabetes was diagnosed.

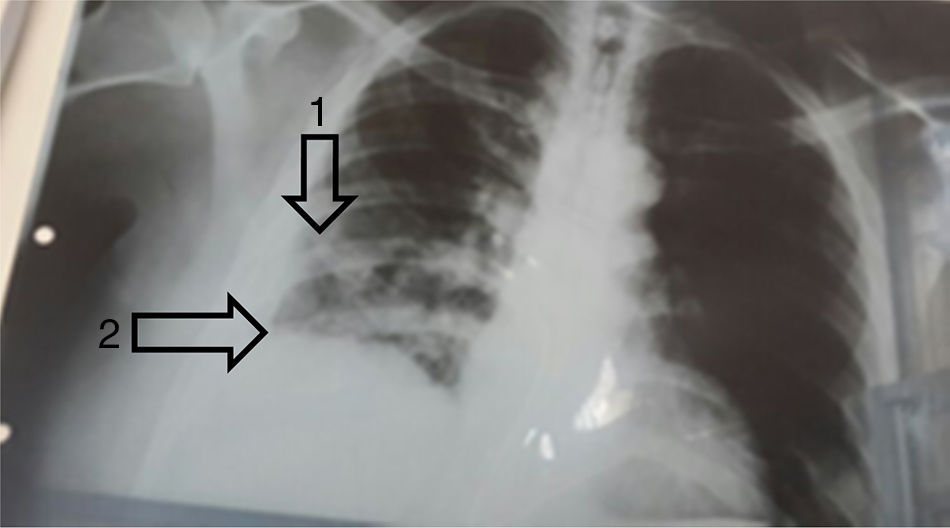

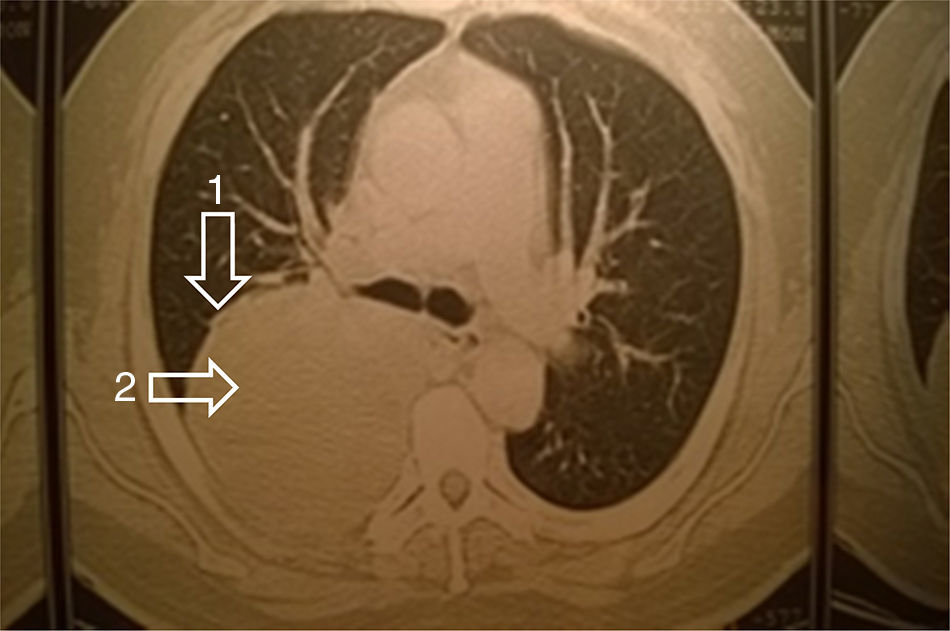

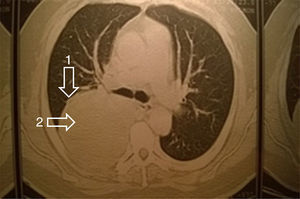

An empyema was observed in the right lower lobe by a chest radiograph (Fig. 1) and by computerized axial tomography (Fig. 2).

The patient was taken to the operating room where decortication and atypical lung resection were performed. An empyema and lung necrosis were observed. Samples of mucopurulent pleural fluid, pleural biopsy and pulmonary parenchyma were obtained and three drainage tubes were left at the site. Pleural fluid contained neutrophils, histiocytes but no neoplastic cells. The pleural biopsy showed cell debris, fibrinoid necrosis and granulation tissue. The pulmonary parenchyma also showed inflammatory cells and granulation tissue compatible with a lung abscess in way of organization.

GBS serotype III was isolated from the pleural fluid cultured in blood agar and chocolate agar plates. Based on Vitek 2 (bio Mérieux Argentina) results, it was susceptible to ampicillin (MIC=0.25μg/ml), erythromycin (MIC=0.25μg/ml), clindamycin (MIC=0.25μg/ml) and vancomycin (MIC=0.5μg/ml) but resistant to tretracycline (≥16μg/ml).

The patient first received ceftazidime (2g/8h i.v.)+clindamycin (300mg/8h) for 18 days and then he was discharged home and orally treated with amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (1g/12h) for 23 days with an uneventful evolution.

The use of ceftazidime+clindamycin was indicated despite not being the elective option for community-acquired pneumonia. As it was effective in improving the patient's condition, it was not changed to another scheme covering a reduced spectrum. Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was the antibiotic of choice for oral treatment because of dosing convenience and the possibility of the presence of non-detected anaerobic bacteria, taking into account that it was a necrotizing pneumonia.

Pneumonia due to GBS almost exclusively occurs in older debilitated adults with central nervous system dysfunction. It is often associated with health care and results in high case-fatality rate3. Chest radiographs reveal lobar or multilobar infiltrates that are not usually associated with pleural reactions4, lung tissue necrosis being rare9.

The present case occurred in a 48-years-old diabetic man without CNS involvement, who survived after appropriate treatment. Though concomitant organisms are frequently found, GBS was the unique causal agent in this case.

In nonpregnant adults, types Ia, III, and V account for 66–83% of isolates causing invasive infection in the United States1. The most commonly identified type in nonpregnant adults has been serotype V, accounting for 24–31% of invasive isolates1.

In Argentina, only one study included GBS from nonpregnant adults with invasive infections6. Serotypes II, Ia/c, III, and IV were commonly found, with serotype II being prevalent in younger adults (18–69 years old) and serotype Ia/c being prevalent in elderly adults (>70 years old). GBS attributable mortality assessed in that study was 11.5%, and included a 30-year-old man suffering from AIDS, pneumonia and ascitis, who died suddenly as a consequence of streptococcal bacteremia6.

To conclude, we present this case to highlight the necrotizing nature of pneumonia and the success of the antimicrobial treatment. As in cases of invasive infection by Streptococcus pyogenes, clindamycin could prevent streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, since GBS may also produce pyrogenic toxins.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.