Fusarium wilt of cucumber, caused by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum, is a major plant disease that causes significant economic losses. The extensive use of chemical fungicides for its control poses environmental and health risks. Due to growing concerns about the detrimental effects of chemical fungicides, finding safe and effective bio-based alternatives for plant disease control is of high importance. In this study, the potential of Neowestiellopsis persica A1387 cyanobacterial metabolites as a promising substitute for chemical fungicides in controlling this disease was investigated. The antifungal activity of N. persica A1387 cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide (EPS) extract was evaluated against F. oxysporum under in vitro and in vivo conditions. Cucumber plants infected with the fungus were treated with cyanobacterial EPS extract and then assessed for disease severity, antioxidant enzyme activity, and growth parameters. Both biomass and EPS extracts of N. persica A1387 cyanobacteria significantly increased the diameter of the F. oxysporum growth inhibition zone under in vitro conditions. Treatment with cyanobacterial EPS extract resulted in increased dry and fresh weight of stem and roots, and a significant reduction in disease severity and percentage in F. oxysporum-infected plants. Peroxidase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase enzyme activities in fungus-infected plants treated with cyanobacterial EPS extract were significantly lower on day 42 of infection compared to untreated and infected control plants. These findings demonstrate the potential of N. persica A1387 cyanobacterial extracts as natural and safe alternatives to chemical fungicides for controlling cucumber Fusarium wilt disease.

Debido a las crecientes preocupaciones sobre los efectos perjudiciales de los fungicidas químicos, es de gran importancia encontrar alternativas de base biológica seguras y eficaces para el control de enfermedades de plantas. En este estudio, se investigó el potencial de los metabolitos de la cianobacteria Neowestiellopsis persica A1387 para controlar la marchitez del pepino, causada por el hongo Fusarium oxysporum. La actividad antifúngica del extracto de exopolisacáridos (EPS) de dicha cianobacteria contra F. oxysporum se evaluó in vitro e in vivo. Las plantas de pepino infectadas con el hongo se trataron con extracto de EPS y de la biomasa de la cianobacteria y luego se evaluaron la gravedad de la enfermedad, la actividad de enzimas antioxidantes y los parámetros de crecimiento. Tanto los extractos de biomasa como de EPS aumentaron significativamente el diámetro de la zona de inhibición de F. oxysporumin vitro. El extracto de EPS provocó un aumento del peso seco y fresco del tallo y las raíces, y una reducción significativa en la gravedad de la enfermedad y el porcentaje de plantas infectadas con el patógeno in vivo. Al día 42 de la infección, las actividades de las enzimas antioxidantes peroxidasa, superóxido dismutasa y catalasa en las plantas infectadas por el hongo y tratadas con el extracto de EPS fueron significativamente más bajas que en las plantas infectadas y no tratadas. Estos hallazgos demuestran el potencial de los extractos de N. persica A1387 como una alternativa natural y segura a los fungicidas químicos para controlar el marchitamiento del pepino.

Plants are essential for human life, providing 50% of the food we need. Given their importance and role in food security, efforts to increase plant production and protect them from pests and diseases are of paramount importance6. Plant pathogens cause diseases such as root rot, wilt, and seedling death, leading to reduced crop yields. In recent decades, the use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers has posed a serious threat to human health and disrupted ecosystem balance17.

Fusarium stem and root rot is one of the most important soilborne diseases of cucumber, causing significant damage to the crop in greenhouses. Cucumber is an important and popular vegetable worldwide that can be severely infected by Fusarium oxysporum Schlechten. Fr. f. sp. cucumerinum Owen39. Fusarium wilt (F. oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum) is one of the most important diseases of cucumber. Fusarium wilt of cucumber is a major and serious vascular disease worldwide and is recognized as a yield-limiting factor in cucumber production, occurring at all stages of cucumber growth. This disease is usually specific to cucumber; however, it can also infect other plants such as watermelon and melon, but the severity and symptoms of the disease in these plants are less than in cucumber37. When a cucumber plant is attacked by Fusarium wilt disease, the fungus enters the roots and becomes confined to the vascular tissues40. The leaves of infected plants or parts of them lose their turgidity and change color from light green to yellowish green, wilt, and eventually turn yellow and brown and die. The main characteristic of all vascular wilt diseases is the colonization and browning of vascular tissues that occur due to various pathogenic factors, including mycelia, spores, polysaccharides, and toxins of pathogenic agents, leading to the obstruction of xylem vessels and water stress as a result of multiple factors22.

To prevent crop losses due to plant diseases, various control methods are used. The use of chemical compounds is the most common method for controlling fungal diseases in fields and greenhouses34. Chemical control requires high costs and the use of various chemical pesticides, which cause health and environmental problems. Unfortunately, the use of chemical pesticides, including fungicides, in this context has led to many environmental hazards, including the destruction of non-target organisms and the emergence of pesticide-resistant pathogens. Therefore, the strategy of biological control and the replacement of chemical pesticides with safe biological agents have been proposed, and the use of alternative methods for pathogen control, such as biological control, is an important matter in integrated pest management38.

Nowadays, natural compounds (secondary metabolites) are an important source of new drugs and effective drug compounds. Natural products are not only used in their own right as medicines, but may also serve as structural models for the creation of synthetic analogs and as models in structure–activity studies7. The wide variety of biological and chemical activities of cyanobacterial secondary metabolites makes these microorganisms a significant source of new drugs for use in various therapeutic areas25,27. The use of bioactive compounds produced by cyanobacteria for plant disease control has many advantages over other methods. The abundance of cyanobacterial habitats and resources, phototrophy, and the lack of organic matter requirements in cyanobacterial cultivation are economic advantages from a biotechnological point of view that give cyanobacteria an advantage over other microorganisms. Moreover, the existence of special metabolic pathways and our limited knowledge of these organisms enhance the possibility of finding new compounds in these microorganisms31. Therefore, cyanobacteria are among the microorganisms that are widely screened for the production of new compounds today, and many compounds with different biological capabilities have been identified from them, including antimicrobial compounds. Various studies have shown that the incidence of many diseases in plants and plant products can be reduced by using the antagonistic properties of compounds present in cyanobacteria. However, the search to understand the inhibitory effect of cyanobacterial extracts is important in many aspects26.

Recently, some cyanobacteria such as Anabaena variabilis RPAN59 and Anabaena oscillarioides RPAN69 have proved to be successful as antagonists against Pythium debaryanum, F. oxysporum, Alternaria alternata f. sp. lycopersici, F. moniliforme and Rhizoctonia solani9. Genus Neowestiellopsis, originally described by Kabirnataj et al. (2018) from Mazandaran (Iran)15, belongs to the order Nostocales and the Hapalosiphonaceae family. Strains of this genus can be found in both paddy fields and agricultural zones, and, due to their ability to fix nitrogen, some strains have an important role in agriculture2,14. After that, Nowruzi et al. (2022), using a polyphasic approach24, found evidence of human poisoning resulting from the ingestion of Crataegus plant crops contaminated with cyanobacterial toxins from Neowestiellopsis ca. persica, which is most abundant in the agricultural zones of Kermanshah province of Iran. They recorded the presence of a gene cluster coding for the biosynthesis of a bioactive compound (Nostopeptolides) that is very rare in this family and contains toxic compounds (microcystins), which could be responsible for human poisoning29. Therefore for a deeper understanding of the genus Neowestiellopsis, in vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of extracellular metabolites of N. persica strain A1387 against Fusarium wilt of cucumber caused by F. oxysporum have been conducted.

Materials and methodsCultivation of cyanobacterial strain N. persica A1387Initially, the N. persica A1387 cyanobacterial strain was cultured on BG-11 solid culture medium. After ensuring purity and absence of contamination in the culture, it was transferred to culture flasks in a growth chamber. The cultivation of the purified samples was carried out in a growth chamber at 28°C and continuous fluorescent light with an intensity of 300μE/m2/s for 30 days33.

Separation of cell extracts and concentration of cyanobacterial exopolysaccharides (EPS)To separate cells and concentrate (EPS), cells were first centrifuged at 15000×g for 20min, and the supernatant was collected and concentrated to 0.1 of the initial volume using a rotary evaporator. The concentrated EPS solution was then dialyzed against distilled water using a 3500 Dalton cut-off dialysis membrane for 48h. Next, twice the volume of cold ethanol was added to the dialyzed EPS solution, and the mixture was stored at 4°C for 24h. The EPS precipitate was then collected by centrifugation at 10000×g for 15min, washed with cold ethanol, and centrifuged again. EPS was collected by centrifugation at 6000×g for 15min and finally dried at 55°C for 72h. The dried cells were powdered and extracted with 90% methanol for 24h at room temperature. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 10000×g for 15min and then evaporated to dryness. The flakes were dissolved in deionized water to a concentration of 0.3%18.

Cyanobacterial biomass extract was obtained by the modified method of Nowruzi et al. (2012). At the stationary phase of growth (15 days), the collected biomass was freeze-dried and resuspend in methanol (1ml) and collected in 2ml plastic tubes containing approximately 200ml of 500mm glass beads (Scientific Industries, New York) using Fast Prep homogenizer (FP120, Bio 101, Savant) at a speed value of 6.5mm/s. After centrifugation at 20000rpm for 5min, supernatant was collected and biological activity was evaluated30.

Cultivation and inoculation of cucumber seedsTo investigate greenhouse conditions, the method described by Huang et al. (2017) was used with some minor modifications. Cucumber seeds were surface disinfected with 2% hypochlorite for 3min and washed three times with sterile distilled water. Then, a sterile moistened filter paper was placed in sterile petri dishes, and the seeds were placed in each petri dish using sterile forceps under a hood. The seeds were then incubated in an incubator at 30°C for 24h to germinate. Healthy germinated seeds were selected, and 78 pots were planted with three seeds in each pot13.

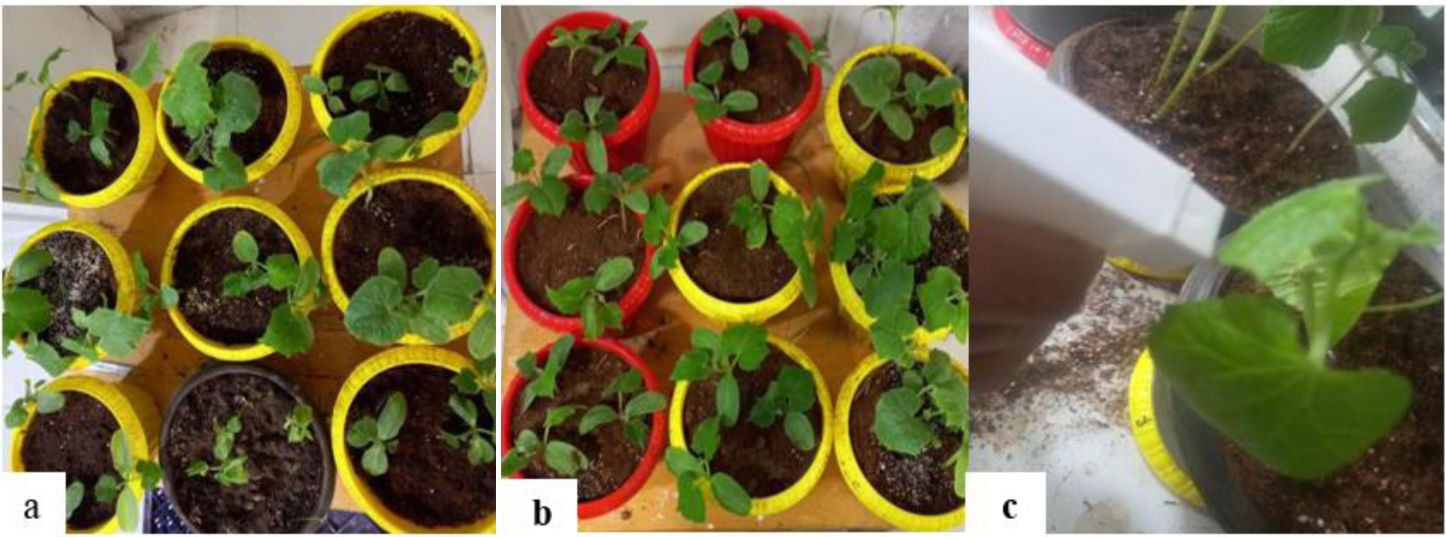

Before planting the seeds, the culture medium was contaminated with spore suspension. In this way, the spores were removed from the one-week culture of the mold on the PDA culture medium in a completely sterile environment and the concentration of the suspension was adjusted to 105 spores per milliliter. Then 50ml of spore suspension was added to each of the pots with a diameter of 15cm and mixed with the substrate5 (Fig. 1).

Inoculation of infected pots with N. persica extractN. persica extract was inoculated into the cucumber plants at 20 and 34 days after the germination. Then the pots were divided into four different groups of (a): healthy control, (b) F. oxysporum-infected pots without cyanobacterial extract after 28 days, (c) F. oxysporum-infected pots inoculated with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract (day 42), and (d) F. oxysporum-infected pots inoculated with cyanobacterial biomass extract (42 days). Each group consisted of three pots, with each pot containing three cucumber seeds, making a total of three replicates per treatment.

Experiments were conducted in the greenhouse at a temperature of 25–30°C during the day and 16°C at night with 12h of light and 12h of darkness. The pots were watered once every two days and three cucumber seeds were planted in each pot. The intensity of pollution was measured using the method of Kui Van et al. (2005) with some modifications. In this method, a scoring range of zero to five was used. Zero=no symptoms, one=wound length ≥1cm, two=wound length 2.15cm, three=wound length ≥5.2cm, four=5cm, or the canker has covered the entire stem and five=seedling death13 (Fig. 2).

Comparison of infected and control cucumber plants: (a) F. oxysporum-infected pots without cyanobacterial extract after 28 days; (b) F. oxysporum-infected pots inoculated with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract (day 42); (c) F. oxysporum-infected pots inoculated with cyanobacterial biomass extract (42 days); (d) control (without F. oxysporum and cyanobacterial extract).

Disease severity of cucumber plant was recorded at 42 days using a disease index (0–5) scale: 0=no infection, 1=≥1cm of infected cucumber area, 2=≥2.5cm of infected cucumber area, 3=≥3cm of infected cucumber area, 4=≥4cm of infected cucumber area, and 5=death of the seedling.

The disease severity (%) at 42 days was determined according to the following equation:

where n is the number of cucumbers within each infection category, V is the numerical values of infection categories, N is the total number of cucumbers examined, and 4 is the constant of the highest numerical value.Antifungal activity assayF. oxysporum was grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium in surface culture. After inoculation, the cultures were incubated at 25°C for 7 days. To determine antifungal activity, methanolic extract, exopolysaccharide suspension, and methanol alone were used at different concentrations of 1, 5, 10, and 20mg/ml. The radial growth of fungi was recorded from day 1 to day 5, and the percentage inhibition of cyanobacterial methanolic extract relative to the control was calculated using the following formula:

- •

I: radial growth of fungi in cyanobacterial extract-treated plates

- •

C: percentage inhibition

- •

T: radial growth of fungi in control plates

The MIC was performed in 10 tubes (16mm×160mm) containing 1ml of Saubouraud dextrose broth with 1ml of various dilutions of cyanobacterial biomass extract and cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension at a concentration of 20mg/ml and 100μl of suspension containing 104 spore ml of fungi cultures according to the standard reference method (NCCLS, 2008). The required concentration of the extract was dissolved in 1ml of Saubouraud dextrose broth and diluted to produce serial two-fold dilutions ranging from 500 to 0.97. Tubes 11 and 12 were considered controls containing 1ml Saubouraud dextrose broth with 1ml of cyanobacterial extract (500mg/ml) and 1ml Saubouraud dextrose broth with 100μl of fungi cultures respectively. Tubes were incubated at 27°C for 2 days. Fungal growth in tubes was assessed visually. One microliter of the presumed tested broth was placed on the sterile Saubouraud dextrose agar as the lowest concentration of the compound inhibiting the visual growth of the test cultures on the agar plate. If no visible growth is observed, the MIC is considered to be MBC.

Measurement of plant growth indicesFresh weight of aerial and root organs was measured separately after detaching the plant from the root collar and dividing it into two parts, stem and root, and washing and drying both parts. Dry weight of aerial and root organs was also measured after placing the samples in an oven at 70°C for 48h3.

Extract preparation and enzymatic extractionMeasurements of peroxidase and plant protein were conducted using treated plants. To achieve this objective, the enzyme extract of the plants was obtained using a modified method described by Abo-Elyosr et al.1. The protein extract (enzyme extract) was obtained using the method described by Kar and Mishra (1976), with slight modifications. The quantity of 300mg of fresh leaf tissue was measured, then fragmented and thoroughly pulverized in a Chinese mortar utilizing liquid nitrogen. Next, 2ml of a potassium phosphate buffer with a concentration of 100mM and a pH of 7.2 was carefully added and thoroughly mixed. The sample was transferred to a 5ml microtube and then centrifuged at 17,000×g for 15min at a temperature of 4°C. Next, the liquid portion was carefully moved to small microtubes and kept at a temperature of −20°C until the activity of the enzyme was assessed16.

Measurement of peroxidase activityPeroxidase activity (POD) was estimated using guaiacol, a reaction solution composed of 10mM (KH2PO4/K2HPO4, pH 7.0), 10mM H2O2, 20mM guaiacol, and 0.5ml crude extract in a final volume of 3ml. The increase in absorbance as a result of the formation of tetra guaiacol was recorded at 470nm36.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD)The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) (EC 1.15.1.1) was assessed using a colorimetric method, including the measurement of formazan crystals at 20 and 34 days. This was done by mixing 50mM potassium-phosphate (K-PO4) buffer solution (pH 7.8), 0.1mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 75mM nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), 7 16/M riboflavin, and the enzyme extract. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was then measured at 560nm. Then, the negative control sample containing the above solution except the cell-free extract was exposed to fluorescent light as a control for comparison and final calculation, reporting results in U/min/mg/protein10.

Catalase (CAT)The activity of catalase (CAT) (EC 1.11.1.6) was assessed in a reaction mixture containing 50mM K-PO4 buffer (pH 7.0), distilled water, 12.5mM H2O2, and an extract solution at 20 and 34 days. Absorbance was measured at 540nm11.

Statistical analysis methodResults obtained in the experiments for experimental data were expressed as mean±standard deviation from measurements with three replicates. Colony forming units (CFUs) were transformed to their logarithmic values before the statistical analysis in all experiments. Experimental data were compared using one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA). Significant statistical differences between mean values (in cases where the overall effect of treatments was significant) were determined using Duncan's multiple range follow-up test. Statistical tests for the results obtained were performed using SPSS software version 26. A significance level of (p≤0.05) was considered for all data comparisons.

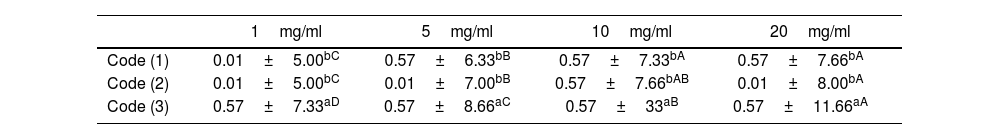

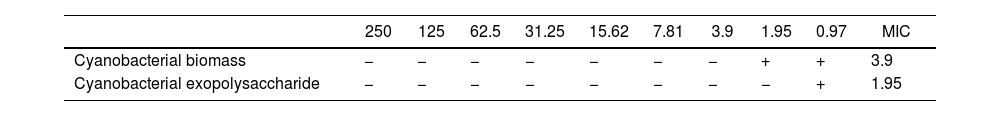

ResultsAntifungal activity of cyanobacterial extractsResults of the one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's test with a probability level of less than 0.05 showed that with increasing concentration of cyanobacterial biomass extract suspension and cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension, the diameter of the growth inhibition zone increased significantly (p≤0.05). However, no significant difference was found in the diameter of growth inhibition between cyanobacterial biomass extract and cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension at different concentrations (p≤0.05) (Table 1). The results indicated that the MICs of cyanobacterial biomass extract suspension was 3.9mg/ml, whereas it was 1.95 in the case of cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension. As illustrated in the “Results” section, some variations were observed across experiments and it became clear that a given bioactive isolate did not necessarily show clearing at all times (Table 2).

Results of antifungal activity of cyanobacterial extracts at different concentrations against F. oxysporum (growth inhibition zone diameter in mm).

| 1mg/ml | 5mg/ml | 10mg/ml | 20mg/ml | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code (1) | 0.01±5.00bC | 0.57±6.33bB | 0.57±7.33bA | 0.57±7.66bA |

| Code (2) | 0.01±5.00bC | 0.01±7.00bB | 0.57±7.66bAB | 0.01±8.00bA |

| Code (3) | 0.57±7.33aD | 0.57±8.66aC | 0.57±33aB | 0.57±11.66aA |

Different lowercase letters indicate a significant difference in the column and different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference in the row (p≤0.05).

Code (1): cyanobacterial biomass extract suspension; Code (2): cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension; Code (3): methanol.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of cyanobacterial biomass extract and cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension against F. oxysporum.

| 250 | 125 | 62.5 | 31.25 | 15.62 | 7.81 | 3.9 | 1.95 | 0.97 | MIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanobacterial biomass | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | 3.9 |

| Cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | 1.95 |

(−): no growth observed; (+): growth observed.

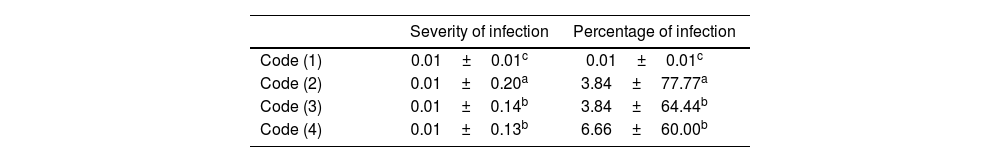

The results of the one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test with a probability level of less than 0.05 showed that the lowest level of severity and percentage of infection belonged to Code 1 (uninfected plant) and the highest level to Code 2 (infected control with F. oxysporum and untreated).

Furthermore, there was no significant statistical difference in the severity and percentage of infection between Code 4 (F. oxysporum-infected plant treated with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension) and Code 3 (F. oxysporum-infected plant treated with cyanobacterial biomass extract suspension) (Table 3).

Results of fungal disease severity and percentage of infection in cyanobacterial extract-treated and non-treated samples (42 days post-inoculation).

| Severity of infection | Percentage of infection | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Code (1) | 0.01±0.01c | 0.01±0.01c | |

| Code (2) | 0.01±0.20a | 3.84±77.77a | |

| Code (3) | 0.01±0.14b | 3.84±64.44b | |

| Code (4) | 0.01±0.13b | 6.66±60.00b |

Lowercase letters indicate a significant difference between samples in the column (p≤0.05).

Code (1): uninfected plant; Code (2): F. oxysporum-infected control and untreated; Code (3): F. oxysporum-infected plant treated with cyanobacterial biomass extract suspension (20mg/ml); Code (4): F. oxysporum-infected plant treated with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension (20mg/ml).

The results of the one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test with a probability level of less than 0.05 showed that the highest dry and fresh weight of stem and roots after infection belonged to F. oxysporum-infected plants treated with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension, and the lowest stem and root dry and fresh weight belonged to F. oxysporum-infected plants that were not treated.

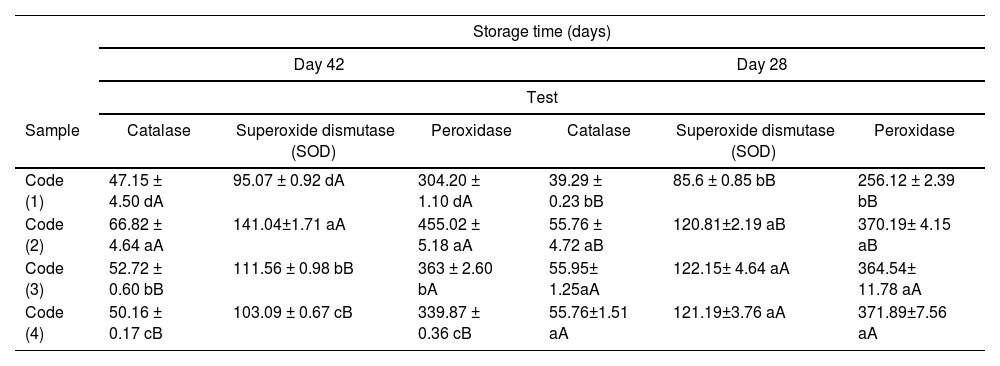

Evaluation of the results of measuring the activity of peroxidase, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalaseThe results of the one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test with a probability level of less than 0.05 showed that on day 28 of infection, the control Code exhibited the lowest activity of peroxidase, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (p≤0.05), and there was no significant statistical difference in the activity of these enzymes in the other treatments (p>0.05). On day 42, the highest activity of peroxidase, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase was observed in Code 2 (control infected with F. oxysporum and untreated), and the lowest activity of these enzymes was initially observed in Code 1 (uninfected plant) and then in Code 4 (plant infected with F. oxysporum and treated with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension) (p≤0.05). In general, it can be stated that increasing the concentration of cyanobacterial extract suspension further reduced the activity of peroxidase, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (p≤0.05).

On the other hand, over time, the activity of peroxidase in Codes 1 (uninfected plant) and Code 2 (control infected with F. oxysporum and untreated) increased significantly, while a significant decrease in peroxidase enzyme activity was observed in Code 4 (plant infected with F. oxysporum and treated with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension) (p≤0.05). In Code 3 (plant infected with F. oxysporum and treated with cyanobacterial biomass extract suspension), no significant statistical difference in peroxidase enzyme activity was observed over time (p≤0.05). However, time had a significant effect on the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase in treatment 3 (Table 4).

Results of changes in peroxidase, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase activity in samples over time.

| Storage time (days) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 42 | Day 28 | |||||

| Test | ||||||

| Sample | Catalase | Superoxide dismutase (SOD) | Peroxidase | Catalase | Superoxide dismutase (SOD) | Peroxidase |

| Code (1) | 47.15 ± 4.50 dA | 95.07 ± 0.92 dA | 304.20 ± 1.10 dA | 39.29 ± 0.23 bB | 85.6 ± 0.85 bB | 256.12 ± 2.39 bB |

| Code (2) | 66.82 ± 4.64 aA | 141.04±1.71 aA | 455.02 ± 5.18 aA | 55.76 ± 4.72 aB | 120.81±2.19 aB | 370.19± 4.15 aB |

| Code (3) | 52.72 ± 0.60 bB | 111.56 ± 0.98 bB | 363 ± 2.60 bA | 55.95± 1.25aA | 122.15± 4.64 aA | 364.54± 11.78 aA |

| Code (4) | 50.16 ± 0.17 cB | 103.09 ± 0.67 cB | 339.87 ± 0.36 cB | 55.76±1.51 aA | 121.19±3.76 aA | 371.89±7.56 aA |

Lowercase letters indicate a significant difference within a column and uppercase letters indicate a significant difference within a row (p≤0.05).

Code (1): uninfected plant; Code (2): F. oxysporum-infected control and untreated; Code (3): F. oxysporum-infected plant treated with cyanobacterial biomass extract suspension; Code (4): F. oxysporum-infected plant treated with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract suspension.

Cyanobacteria are rich sources of numerous phytochemical compounds with inherent antifungal potential. These organisms produce a wide range of antifungal compounds, including peptides, polyketides, and alkaloids. Extensive research has been conducted on the antifungal effects of cyanobacterial metabolites. Researchers have investigated cyanobacteria for their role in the biological control of plant-pathogenic fungi, demonstrating that they exhibit antifungal effects against various plant pathogens28. For instance, Kim et al. (2006) examined cyanobacteria isolated from rice paddy soils and found that nine out of 20 species displayed significant antifungal activity. These species included Oscillatoria and Anabaena, which were particularly effective against Alternaria alternata and Botrytis cinerea. Additionally19, Marrez et al. (2016) reported that extracts of the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa, obtained through various extraction methods, exhibited potent antifungal activity against mycotoxigenic fungi and significantly inhibited their growth21.

The results of our study demonstrated that the exopolysaccharide and biomass extracts of the cyanobacterium Neowestiellopsis persica significantly increased the inhibition zone diameter of F. oxysporum under in vitro conditions. These findings are consistent with those of Righini et al. (2019), who reported the efficacy of cyanobacterial polysaccharides in inhibiting the growth of plant-pathogenic fungi such as Botrytis cinerea. Furthermore, the MIC of the cyanobacterial extracts revealed that even at lower concentrations, these compounds exhibited substantial inhibitory effects. In this context, the findings of the present study confirm the potential of N. persica as an effective biocontrol agent against Fusarium wilt in cucumber under in vitro conditions35.

In line with the findings of this study, treatment with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide and biomass extracts significantly reduced the severity and percentage of Fusarium wilt infection in cucumber. These results are consistent with previous studies on the antifungal potential of cyanobacterial extracts against F. oxysporum. For example, Alallaf et al. (2023) tested the antifungal potential of Desertifilum tharense PS 11 extracts with various solvents under laboratory conditions against F. oxysporum. The results indicated a 50% reduction in disease incidence. The methanolic extract of D. tharense exhibited a significant effect on plant growth and tomato yield. Therefore, this study clearly demonstrated that the methanolic extract of D. tharense PS 11 is a promising biochemical control agent against F. oxysporum and can enhance tomato growth4.

The results of this study demonstrated that F. oxysporum infection significantly reduced plant growth (decreased dry and fresh weight of stems and roots in Table 3, Code 2). Treatment with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract partially alleviated the negative effects of this infection (increased dry and fresh weight of stems and roots in Table 3, Code 4). The protective effect of the cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract was greater than that of the cyanobacterial biomass extract (comparison of Codes 4 and 3 in Table 3). Plant health plays a crucial role in its growth and development (highest dry and fresh weight of stems and roots in Table 3, Code 1). These findings are consistent with those of Mahawar et al. (2019), who showed that treatment with cyanobacterial extract or copper nanoparticles increased root and shoot growth in tomato plants infected with Fusarium fungus20.

The results also showed that the activities of peroxidase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase in F. oxysporum-infected plants treated with N. persica cyanobacterial extracts significantly decreased on day 42. The highest enzyme activities were observed in infected, untreated plants (Code 2), indicating that the untreated infected plants exhibited the highest enzymatic activity in response to disease stress. On day 28, the lowest activities of peroxidase, SOD, and catalase were recorded in the control sample (non-infected plants), suggesting that healthy plants exhibit minimal enzymatic activity under normal conditions. These findings suggest that cyanobacterial extracts reduced stress caused by fungal infection, leading to a decrease in antioxidant enzyme activity.

Additionally, a comparison of antioxidant enzyme activities in plants treated with exopolysaccharide extract (Code 4) and biomass extract (Code 3) revealed that the reduction in enzyme activities was greater in the plants treated with exopolysaccharide extract. This suggests that the exopolysaccharide extract is more effective in mitigating oxidative stress induced by F. oxysporum. The activities of peroxidase, SOD, and catalase in Code 4 (plants infected with F. oxysporum and treated with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract) were significantly lower than those in Code 2 (infected plants without treatment). This reduction in enzyme activities in Code 4 can be attributed to plant recovery and the alleviation of stress caused by Fusarium wilt due to treatment with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that biotic and abiotic stresses can lead to changes in antioxidant enzyme activities in plants. For example, Hernandez et al. (2000) showed that peroxidase activity increases in plants under drought stress12.

Previous studies have also shown that cyanobacterial extracts can enhance antioxidant enzyme activities in plants and help protect them from biotic and abiotic stresses. For instance, Gaafar et al. (2022) demonstrated that in wheat plants, the induction of defense antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT, GPX, GST, and the non-enzymatic molecule GSH increased following treatment with Arthrospira platensis extract8. Similarly, Mutale-joan et al. (2021), in their study on the effects of cyanobacterial extracts from Dunaliella salina, Chlorella ellipsoidea, Aphanothece sp., and Arthrospira maxima on potato plants under environmental stress, found that lipid peroxidation in leaves due to oxidative stress (ROS) was significantly reduced by the increased activities of CAT and SOD in cyanobacterial extract-treated plants. These extracts also significantly reduced fatty acid content, indicating the conversion of fatty acids to other lipid forms, such as alkanes, which are essential for cuticular wax synthesis in plants under water stress23. Priya et al. (2015) reported that the use of the cyanobacterial strain Calothrix elenkenii in flooded rice fields led to an increase in the expression levels of certain plant defense enzymes32.

However, the results of the present study showed that the addition of cyanobacterial extracts under stress conditions resulted in a significant decrease in antioxidant enzyme activity over time, reflecting the efficacy of bioactive cyanobacterial compounds in combating fungal pathogens.

ConclusionThe biomass and exopolysaccharide extracts of the cyanobacterium N. persica strain A1387 exhibited significant antifungal activity against the cucumber wilt pathogen F. oxysporum under in vitro conditions. Treatment of cucumber seeds with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract after inoculation with F. oxysporum significantly reduced the severity and percentage of plant infection with this fungus under greenhouse (in vivo) conditions. Treatment with cyanobacterial exopolysaccharide extract resulted in a significant increase in the dry and fresh weight of stems and roots of infected cucumber plants and a decrease in the activity of peroxidase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase. The findings of this study suggest that the extracts of the cyanobacterium N. persica strain A1387 can be used as an effective biocontrol agent against cucumber Fusarium wilt disease. The use of these extracts can help reduce the use of chemical pesticides and protect the environment. Further research in this area could lead to the development of new and sustainable methods for controlling this and other plant diseases. It is suggested that future research should investigate the effect of applying extracts of other cyanobacterial species on the control of plant diseases, as well as the effect of cyanobacterial extract nanoemulsions on the control of plant diseases and the molecular mechanisms of the antifungal activity of cyanobacterial extracts.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.