Higher mortality is reported among women with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). This study aimed to evaluate the clinical and angiographic profiles, as well as outcomes of patients submitted to primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI), according to gender.

MethodsRetrospective study that included patients with STEMI undergoing pPCI between March 2012 and May 2013 at a regional referral center, followed from admission until hospital discharge or death.

Results208 patients underwent pPCI, of whom 51 (24.5%) were women and 157 (75.5%) men. A significant difference was observed for age (65.5±14.0 vs. 58.8±11.0 years; p=0.001), diabetes (43.1% vs. 24.8%; p=0.02), Killip-Kimball class III/IV (7.0% vs. 17.6%; p=0.02), pain-to-door time (181±154minutes vs. 125±103minutes; p=0.004), and door-to-balloon time (181±87 vs. 133minutes±67minutes; p=0.001). The success of the procedure was similar (92.1% vs. 91.1%; p=0.22). In-hospital mortality was higher for females (23.5% vs. 8.9%; p=0.006). Multivariate analysis identified age ≥70 years (odds ratio - OR=2.75; 95% confidence interval - 95% CI: 1.81–3.64; p=0.029) and Killip-Kimball class III/IV (OR=2.45; 95% CI: 1.49–4.02; p=0.002) as independent predictors of mortality.

ConclusionsWomen with STEMI had a more severe clinical profile and longer pain-to-door and door-to-balloon times than men. Females had higher in-hospital mortality after pPCI, but the female gender was not identified as an independent predictor of death.

Relata-se maior mortalidade no sexo feminino no infarto do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento de ST (IAMCST). Este estudo teve como objetivo avaliar os perfis clínico e angiográfico, e os resultados de pacientes submetidos à intervenção coronária percutânea primária (ICPp), de acordo com o sexo.

MétodosEstudo retrospectivo que incluiu pacientes com IAMCST submetidos à ICPp entre março de 2012 e maio de 2013, em um serviço de referência regional, acompanhados desde a admissão até a alta hospitalar ou o óbito.

ResultadosForam submetidos à ICPp 208 pacientes, sendo 51 (24,5%) mulheres e 157 (75,5%) homens. Observou-se diferença significativa para idade (65,5±14,0 vs. 58,8±11,0 anos; p=0,001), diabetes (43,1% vs. 24,8%; p=0,02), classificação de Killip-Kimbal III/IV (17,6% vs. 7,0%; p=0,02), tempo dor-porta (181±154 minutos vs. 125±103 minutos; p=0,004) e tempo porta-balão (181±133 minutos vs. 87±67 minutos; p=0,001). O sucesso do procedimento foi semelhante (92,1% vs. 91,1%; p=0,22). A mortalidade hospitalar foi maior para o sexo feminino (23,5% vs. 8,9%; p=0,006). Análise multivariada identificou como preditores independentes de mortalidade a idade ≥70 anos (odds ratio − OR=2,75; intervalo de confiança de 95% − IC 95% 1,81-3,64; p=0,029) e a classe Killip-Kimbal III/IV (OR=2,45; IC 95% 1,49-4,02; p=0,002).

ConclusõesMulheres com IAMCST apresentaram perfil clínico mais grave e tempos dor-porta e porta-balão mais prolongados que homens. O sexo feminino apresentou maior mortalidade hospitalar após ICPp, porém o sexo feminino não foi identificado como preditor independente de óbito.

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is one of the leading causes of death in Brazil and requires well-established protocols for its management, as well as human and technological capacity, which demand ever-increasing financial resources.1

There is strong evidence from randomized clinical trials that primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) is associated with lower mortality, as well as lower rates of recurrent AMI and intracranial bleeding, when compared to fibrinolytic therapy.2 When pPCI is feasible, it is recommended for all patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI) who can undergo the procedure within 90minutes of the first medical contact, performed by qualified professionals, provided that symptoms started within the last 12hours.

STEMI requires immediate identification by the medical team and prompt treatment, involving inter-hospital transfer in some of the cases and specific care services.3 At different points of care, there may be various types of accessibility barriers, usually having clinical, environmental, social, cognitive, and/or emotional causes, and which may be closely related to gender. All these factors can interfere with the medical assessment and decision-making process, as well as the arrival to a health care service or site.4

Several studies have identified different characteristics of STEMI in men and women. Higher mortality is often observed in women, in addition to adverse clinical characteristics at a higher frequency than in men, such as older age, higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, and more severe clinical presentation.5–9 Moreover, longer delay in the care of women with STEMI has been reported, which could influence results, including patients undergoing pPCI.9

This study aimed to evaluate the clinical and angiographic profile pPCI and outcomes of patients undergoing pPCI according to gender, and to obtain the independent predictors of in-hospital mortality.

MethodsStudy design and populationThis was a retrospective, observational, single-center, descriptive, and comparative study (by gender), carried out with data collected from medical records and information obtained and recorded in in the Interventional Cardiology Laboratory.

The sample consisted of consecutive patients admitted with STEMI and undergoing pPCI between March 2012 and May 2013, at a regional referral service, followed from admission until hospital discharge or death. The study included patients older than 18 years undergoing pPCI as an urgent procedure within the first 12hours of symptom onset, treated through the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde [SUS]), with persistent ST-segment elevation in two or more contiguous leads or new left bundle branch block on the electrocardiogram. Patients undergoing PCI with symptom onset for more than 12hours were excluded, as well as those without STEMI diagnostic criteria at the joint assessment by the clinical and interventional cardiology teams.

ProceduresAll cases of STEMI treated at the referral institution had spontaneous demand or were transferred after initial treatment and identification of the clinical picture in another service. The cases requiring inter-hospital transfer were transported by the Mobile Emergency Care Service (SAMU - Serviço de Atendimento Móvel de Urgência), as recommended by the regulatory flow of the Urgency and Emergency Network of the State of Espírito Santo, Brazil. In such cases, the SAMU, contacted by the medical team of the first service after receiving the patient, performed the regulations, contacted the referral service, and conducted the subsequent transfer of the patient in an appropriate emergency transportation unit.

The emergency nature of the pPCI procedure was taken into account for all patients, who were brought to the catheterization laboratory as soon as possible after notification by the emergency room staff. Patients received a loading dose of 200 to 300mg of acetylsalicylic acid and 300 to 600mg of clopidogrel, or 180mg of ticagrelor. The use of morphine, sublingual/intravenous nitrate, or beta-blocker was at the discretion of the physician. All patients received unfractionated heparin in the cath lab (70 to 100 U/kg). After the procedure, dual antiplatelet therapy was maintained systematically in all patients.

The pPCI was performed as recommended by the Brazilian STEMI guidelines,10 with the access route defined by the interventional cardiologist. Pre- and post-dilation were performed according to the operator's discretion, as well as the administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors.

Myocardial ischemia times were recorded on a routine basis, as well as the time courses of the different stages of medical care. The following were analyzed: pain-to-balloon time (interval between the onset of symptoms and the first balloon inflation); pain-to-door time (interval from symptom onset to arrival at the first health care service); inter-hospital transfer time (time from arrival at the first health care service to the referral hospital); and door-to-balloon time (time between a patient's arrival at the referral hospital and the first balloon inflation).

Definitions and outcomesLength of hospital stay was recorded from the hospital admission day, considered as “day zero”. The hospital stay analysis considered only the patients discharged to home, excluding those who died during the hospitalization period.

The primary endpoint was the occurrence of death from any cause during hospital stay. Secondary outcomes were the occurrence of definite or probable stent thrombosis according to the criteria of the Academic Research Consortium,11 moderate or severe bleeding according to the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries criteria (GUSTO)12 or acute renal failure (characterized by elevated serum creatinine > 50% from baseline or the need for dialysis).

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were expressed as absolute frequency and percentage and compared using Pearson's chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were described as mean and standard deviation and compared using Student's t-test. The obtained data were stored in a Microsoft Office spreadsheet. The analysis was performed using the software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 20.0 for Windows, with p-values < 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

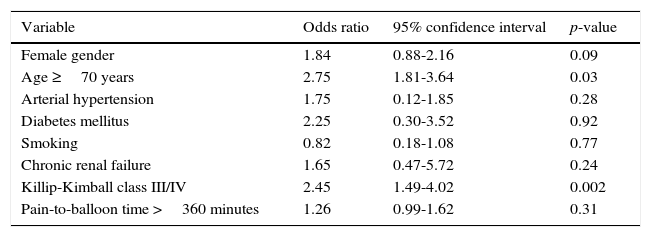

The independent predictors of hospital mortality were obtained by multivariate analysis through binary logistic regression. In the model, the continuous variables were dichotomized, with the female gender, age ≥70 years, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, chronic renal failure, Killip-Kimball class III/IV at admission, and pain-to-balloon time >360minutes used as covariates, while the dependent variable was the occurrence of death during hospitalization.

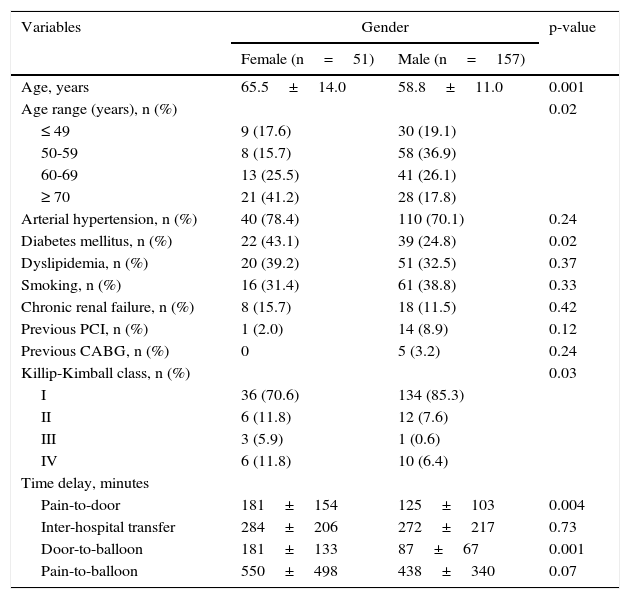

ResultsThe female gender had higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (43.1 vs. 24.8%; p=0.02) and a higher proportion of patients with Killip-Kimball class III/IV (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics.

| Variables | Gender | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n=51) | Male (n=157) | ||

| Age, years | 65.5±14.0 | 58.8±11.0 | 0.001 |

| Age range (years), n (%) | 0.02 | ||

| ≤ 49 | 9 (17.6) | 30 (19.1) | |

| 50-59 | 8 (15.7) | 58 (36.9) | |

| 60-69 | 13 (25.5) | 41 (26.1) | |

| ≥ 70 | 21 (41.2) | 28 (17.8) | |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 40 (78.4) | 110 (70.1) | 0.24 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 22 (43.1) | 39 (24.8) | 0.02 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 20 (39.2) | 51 (32.5) | 0.37 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 16 (31.4) | 61 (38.8) | 0.33 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 8 (15.7) | 18 (11.5) | 0.42 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 1 (2.0) | 14 (8.9) | 0.12 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 0 | 5 (3.2) | 0.24 |

| Killip-Kimball class, n (%) | 0.03 | ||

| I | 36 (70.6) | 134 (85.3) | |

| II | 6 (11.8) | 12 (7.6) | |

| III | 3 (5.9) | 1 (0.6) | |

| IV | 6 (11.8) | 10 (6.4) | |

| Time delay, minutes | |||

| Pain-to-door | 181±154 | 125±103 | 0.004 |

| Inter-hospital transfer | 284±206 | 272±217 | 0.73 |

| Door-to-balloon | 181±133 | 87±67 | 0.001 |

| Pain-to-balloon | 550±498 | 438±340 | 0.07 |

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Of the 208 patients analyzed, 155 (74.5%) were initially treated at another service and transferred to undergo pPCI. There was a higher proportion of inter-hospital transfers among males (60.8 vs. 79.0%; p=0.02). However, this study observed a longer delay for female patients regarding pain-to-door (181±154minutes; vs. 125±103minutes; p=0.004) and door-to-balloon time (181±133minutes vs. 87±67minutes; p=0.001).

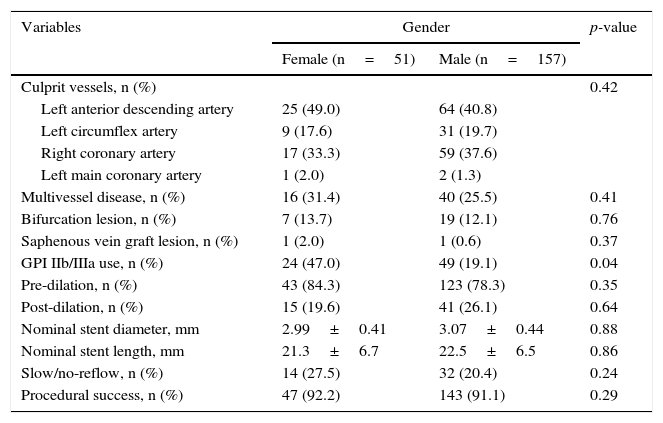

In the total sample, the femoral approach for pPCI was used in 195 procedures (93.7%), while the radial approach was used in the others. A total of 249 coronary stents were implanted, all bare-metal stents, with a mean of 1.2±0.53 stent per patient. The left anterior descending artery was the most often treated vessel in both groups, and the complexity characteristics of treated lesions was not different between groups (Table 2). Pre- (84.3 vs. 78.3%; p=0.35) and post-dilation (19.6 vs. 26%; p=0.64) were also similarly used between the groups, and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor was administered more frequently in women (47.0 vs. 19.1%; p=0.04). Flow disturbances (slow-flow or no-reflow) occurred in 27.5% of women and 20.4% of men (p=0.24). Procedural success rates showed no difference in the comparison between groups (92.1 vs. 91.1%; p=0.22).

Angiographic characteristics.

| Variables | Gender | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n=51) | Male (n=157) | ||

| Culprit vessels, n (%) | 0.42 | ||

| Left anterior descending artery | 25 (49.0) | 64 (40.8) | |

| Left circumflex artery | 9 (17.6) | 31 (19.7) | |

| Right coronary artery | 17 (33.3) | 59 (37.6) | |

| Left main coronary artery | 1 (2.0) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Multivessel disease, n (%) | 16 (31.4) | 40 (25.5) | 0.41 |

| Bifurcation lesion, n (%) | 7 (13.7) | 19 (12.1) | 0.76 |

| Saphenous vein graft lesion, n (%) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.37 |

| GPI IIb/IIIa use, n (%) | 24 (47.0) | 49 (19.1) | 0.04 |

| Pre-dilation, n (%) | 43 (84.3) | 123 (78.3) | 0.35 |

| Post-dilation, n (%) | 15 (19.6) | 41 (26.1) | 0.64 |

| Nominal stent diameter, mm | 2.99±0.41 | 3.07±0.44 | 0.88 |

| Nominal stent length, mm | 21.3±6.7 | 22.5±6.5 | 0.86 |

| Slow/no-reflow, n (%) | 14 (27.5) | 32 (20.4) | 0.24 |

| Procedural success, n (%) | 47 (92.2) | 143 (91.1) | 0.29 |

GPI: glycoprotein inhibitor.

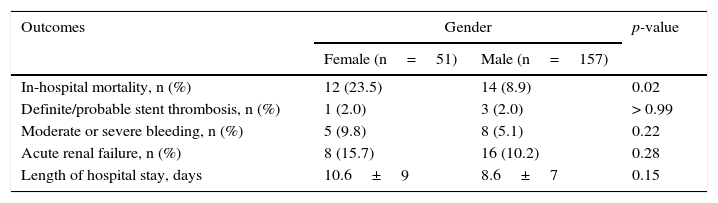

In-hospital mortality of the total sample was 12.5%, and the mean hospital length of stay was 9.1±8.2 days. Higher mortality was observed among female patients (23.5 vs. 8.9%; p=0.02). No stroke cases were diagnosed between groups. Definite/probable stent thrombosis rates (2.0 vs. 2.0%, p>0.99) and moderate/severe bleeding rates (9.8 vs. 5.1%, p=0.22) were not different between groups (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, age and Killip-Kimball class III/IV were identified as factors independently associated with mortality. The female gender was not an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality (Table 4).

In-hospital clinical outcomes.

| Outcomes | Gender | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n=51) | Male (n=157) | ||

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 12 (23.5) | 14 (8.9) | 0.02 |

| Definite/probable stent thrombosis, n (%) | 1 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) | > 0.99 |

| Moderate or severe bleeding, n (%) | 5 (9.8) | 8 (5.1) | 0.22 |

| Acute renal failure, n (%) | 8 (15.7) | 16 (10.2) | 0.28 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 10.6±9 | 8.6±7 | 0.15 |

In-hospital predictors of death after primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 1.84 | 0.88-2.16 | 0.09 |

| Age ≥70 years | 2.75 | 1.81-3.64 | 0.03 |

| Arterial hypertension | 1.75 | 0.12-1.85 | 0.28 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.25 | 0.30-3.52 | 0.92 |

| Smoking | 0.82 | 0.18-1.08 | 0.77 |

| Chronic renal failure | 1.65 | 0.47-5.72 | 0.24 |

| Killip-Kimball class III/IV | 2.45 | 1.49-4.02 | 0.002 |

| Pain-to-balloon time >360 minutes | 1.26 | 0.99-1.62 | 0.31 |

In the 1990s, the MONICA (Multinational MONItoring of Trends and Determinants in CArdiovascular Disease) project of the World Health Organization issued important alerts to the medical community regarding the different characteristics and management of cardiovascular disease in women. The study demonstrated differences between the genders in AMI presentation and management. Women had a more severe clinical presentation than men (Killip-Kimball class III/IV: 11.7 vs. 7.3%; p=0.003); took longer to get to the hospital (< 6hours: 47 vs. 52%; 6 to 12hours: 11 vs. 11%; 12 to 24hours: 7 vs. 7%; >24hours: 35 vs. 30%; p<0.001); and received fewer therapeutic interventions (administration of thrombolytic agents: 42 vs. 58%; p<0.001). The proportion of patients aged ≥ 75 years was higher in women when compared to men (35.1 vs. 17.2%; p<0.001); 56% of men and 41% of women with AMI were admitted to the coronary care unit <24 hours (adjusted odds ratio - OR: 1.40; 95% confidence interval - 95% CI: 1.26 to 1.56). In-hospital mortality was 16% for males and 27% for females (OR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.71-0.97).13

A large international study on the differences between genders in acute coronary syndromes, with the inclusion of over 12,000 patients, showed that women were older than men at the time of STEMI (69 vs. 61 years; p<0.001) and had significantly higher rates of high blood pressure, diabetes, and previous heart failure. They also had lower rates of previous AMI and were less likely to be smokers. Women had more complications during hospitalization and higher mortality at 30 days (6.0 vs. 4.0%; p<0.001). After adjusting for baseline characteristics, the rate of death or reinfarction at 30 days was similar for men and women (p=0.47).14

Data from 4,347 patients hospitalized for AMI in France showed higher in-hospital mortality in women aged 30 to 67 years when compared to men in the same age group (11 vs. 5%; OR: 2.4; 95% CI: 1.4-4.3; p=0.003), where as no difference was observed between men and women in the older age group, namely 68 to 89 years (18 vs. 16%; OR: 1.2; 95% CI: 0.9-1.7; p=0.3). In addition to gender, another significant predictor of in-hospital mortality was the Killip-Kimball class at admission.7

It is known that the reduction in total myocardial ischemia time before coronary reperfusion in STEMI is associated with a decrease in adverse outcomes, including mortality.3,15 However, the Brazilian reality in AMI assistance commonly presents with unnecessary delays and infrequent use of evidence-based therapies within an appropriate timeframe.16 This fact generates a large increase in morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular diseases, affecting a large part of the economically active population and burdening the already scarce financial resources for health care.1

Currently, Brazilian cities generally do not have effective and agile systems for AMI treatment, which cause significant delays in access to referral services. In large cities, most patients first seek care at the Basic Health Units and then are transferred to a referral service to receive adequate treatment, including coronary reperfusion therapy, which cause time delay in the treatment of AMI. Additionally, self-medication and difficulty identifying the disease hinder the timely access to health care services.13

Regional systems of care to optimize timeliness of reperfusion therapy for AMI are strongly recommended, and should be developed and implemented to promote reduction of delay times and improve results in all subpopulations with STEMI. Patients with greater delay before treatment are usually older and have more co-morbidities. A delay > 6hours from symptom onset to the pPCI may represent a nearly two-fold mortality increase compared to that observed when the delay is < 6hours.17

Many of the accessibility barriers, quite poorly studied in the context of STEMI, are prominent in the female gender. Clinical and cultural characteristics, such as atypical clinical presentation, attribution of symptoms to other health problems, and delay in seeking medical care, lead to the association between female gender and delayed AMI treatment.4 The door-to-balloon time in STEMI is often significantly greater in women when compared to men, as shown by Correia et al. (190±86minutes vs. 136±49minutes; p=0.01).18

In the Brazilian population, the female gender has been recognized as an independent variable associated with in-hospital mortality (9.9% for the male gender vs. female, 23%; OR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.19-0.67; p=0.001). Age and Killip-Kimball class have also been confirmed as variables independently associated with increased risk of death in STEMI.6

High clinical complexity was observed among the patients included in this study, with a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors. In addition to this risk profile, there was a great delay in coronary reperfusion by pPCI at the several stages of medical care. This resulted in high in-hospital mortality from STEMI, which reflects the needs of the entire health care system regarding STEMI care through the SUS, from primary prevention in primary care to the high-complexity cardiologic procedures.

Although the female group showed significantly higher in-hospital mortality than the male group, female gender was not an independent predictor of death in this study. The small sample size may justify the absence of an independent association. Therefore, the high mortality observed in women was mainly due to significantly greater clinical severity, older age, and longer delay to treatment in this group, not associated to gender alone.

In addition to gender, other factors were evaluated for in-hospital mortality prediction after pPCI in this population. Among them, it was observed that the Killip-Kimball class III/IV at admission and age ≥70 years were independently associated to the event. Similar results were found for these variables in international studies, demonstrating the high risk of death in STEMI in cases of elderly patients and those with high clinical severity in different populations around the world.7,8

Thus, female patients should be considered regarding their peculiarities in the presence of AMI or other cardiovascular diseases, and this fact should be also emphasized in public health policies and society guidelines, as well as other populations who are at high cardiovascular risk and show significant growth, such as the elderly, patients with chronic kidney disease, and those with diabetes mellitus.

Study limitationsThe patients evaluated in this study correspond only to those who underwent pPCI as coronary reperfusion therapy. A number of patients who did not undergo pPCI or thrombolytic therapy were not accounted for and, therefore, was excluded from this study, showing that the problem illustrates only a part of the patients that were actually treated, and that the systemic deficiencies are indeed even more significant.

The restricted sample size limits the observed results; the convenience sample represents only the population of patients treated in the service where the study was carried out during the given time period and may not represent other populations.

Information bias associated with the assessed time periods may have occurred due to inaccuracies about the time of symptom onset reported by patients and families. Such deviation is inherent in the collected information and has been previously considered in a comprehensive analysis of pPCI results and pain-to-balloon times.19 However, it reflects the factual difficulties found in clinical practice when caring for patients with AMI. The measurement of pain-to-balloon time used in the study, although subject to these biases, should be taken into account, as it reflects the result of joint actions in several critical points of STEMI care, including the identification of symptoms by the patient, accessibility to health services, and quality of emergency pre-hospital care.

ConclusionsFemale patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction had more severe clinical profile and longer pain-to-door and door-to-balloon times than males. Women had higher in-hospital mortality after primary percutaneous coronary intervention, but female gender was not identified as an independent predictor of death.

Funding sourceNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review under the responsability of Sociedade Brasileira de Hemodinâmica e Cardiologia Intervencionista.