Despite the better clinical performance of second-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) when compared to first-generation DES in controlled trials, mainly due to reduction in thrombosis rate, it remains unclear whether this benefit extends to diabetic patients treated in the daily practice. We sought to compare the clinical outcomes of unselected diabetic patients treated with either sirolimus eluting stents - SES (first-generation DES) or everolimus-eluting stents - EES (second-generation DES).

MethodsBetween January 2007 and October 2014 a total of 798 diabetic patients were treated with SES (n = 414) and EES (n = 384). Long-term clinical follow-up was achieved in 99,4% of the population and the groups were compared regarding the occurrence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and stent thrombosis.

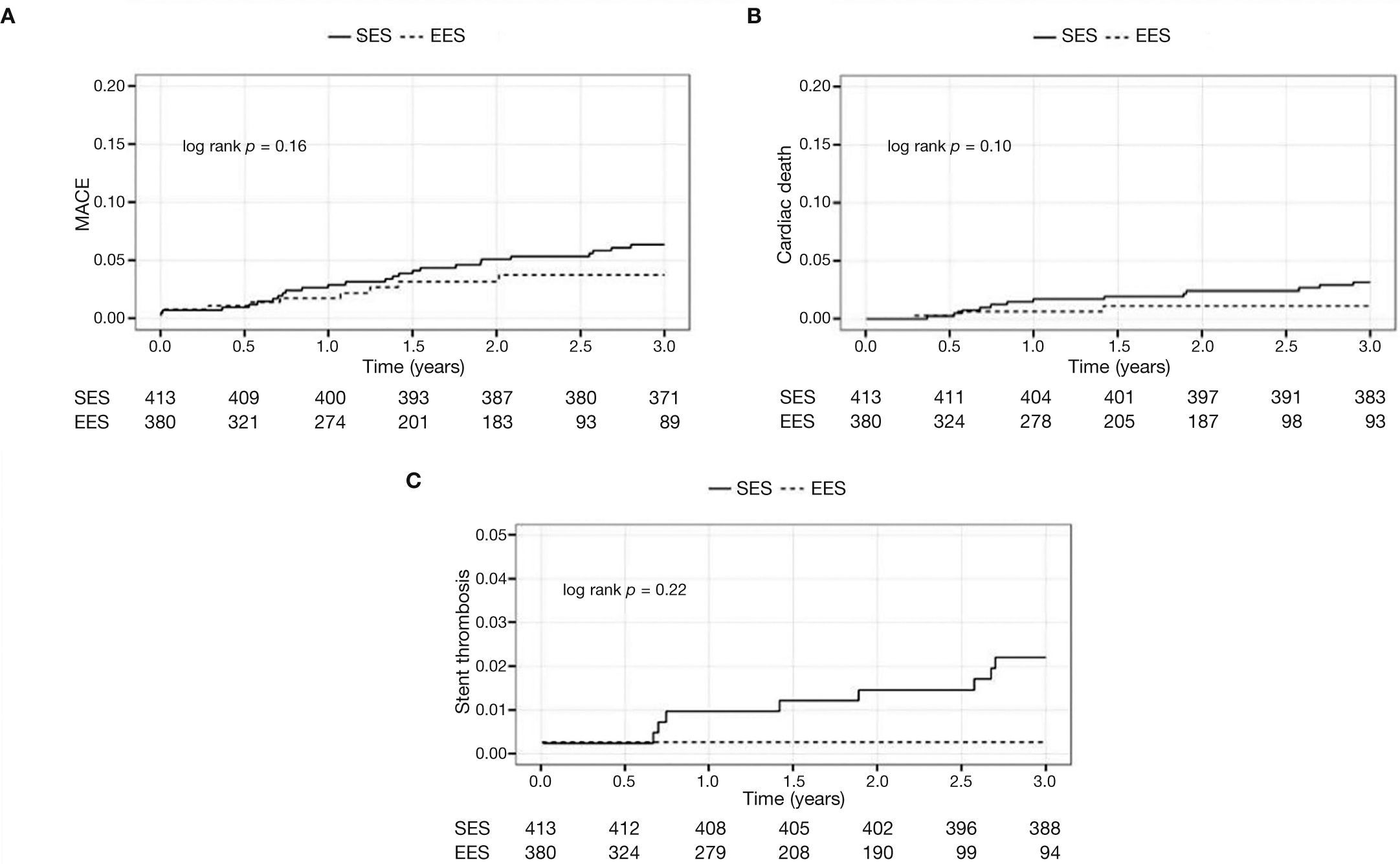

ResultsIn both cohorts age was similar, and most patients were male. Stable coronary disease was the most frequent clinical presentation. The number of treated vessels (1.50 ± 0.62 vs. 1.52 ± 0.72; p = 0.88) and the total stent length (36.1 ± 20.4 vs. 37.7 ± 22.2mm; p = 0.32) were similar between groups. Patients treated with EES showed lower rates of MACE (15% vs. 6.8%, p < 0.001), mainly due to a lower cardiac death (5.3% vs. 1.3%, p < 0.001). There was also less definitive/ probable thrombosis with the second generation DES (3.4% vs. 0.5%, p = 0.004).

ConclusionsIn this single center experience, the use of EES was associated with reduced cardiac death and stent thrombosis. This benefit was mostly observed in the long-term follow-up.

Stents farmacológicos (SF) de segunda geração demonstraram melhor desempenho clínico que os de primeira geração, sobretudo pela redução nas taxas de trombose, mas ainda não está claro se esse benefício se estende a diabéticos da prática diária. Objetivamos comparar o desempenho de pacientes diabéticos não selecionados tratados com SF eluidores de sirolimus (SES; primeira geração) vs. SF eluidores de everolimus (SEE; segunda geração).

MétodosEntre 2007 e 2014, 798 diabéticos foram tratados com SES (n = 414) ou SEE (n = 384) e incluídos nesta análise. Seguimento clínico tardio foi obtido em 99,4% da população e os grupos foram comparados quanto à ocorrência de eventos cardíacos adversos maiores (ECAM) e trombose de stent.

ResultadosA idade da população foi semelhante, com predomínio do sexo masculino. Em ambas as coortes, a apresentação clínica mais frequente foi a doença coronária estável. Número de vasos tratados (1,50 ± 0,62 vs. 1,52 ± 0,72; p = 0,88) e extensão total de stents (36,1 ± 20,4mm vs. 37,7 ± 22,2mm; p = 0,32) foram semelhantes. Os pacientes tratados com SEE apresentaram menores taxas de ECAM (15% vs. 6,8%; p < 0,001), sobretudo à custa de menor mortalidade cardíaca (5,3% vs. 1,3%; p < 0,001). Observou-se também menor ocorrência de trombose de stent definitiva/provável com SF de segunda geração (3,4% vs. 0,5%; p = 0,004). Conclusões: Nesta experiência unicêntrica, o uso de SEE em diabéticos mostrou-se com menor mortalidade cardíaca e trombose da endoprótese. Esse benefício se fez mais evidente no seguimento mais tardio.

The presence of diabetes mellitus increases the risk of cardiovascular disease by two-to four-fold1 and worsens the prognosis of treated individuals,2,3 regardless of coronary revascularization modality (surgical or percutaneous).

It is estimated that approximately 25% of patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are diabetics.4 Even with the advent of drug-eluting stents (DES), which, compared to baremetal stents, greatly reduced restenosis rates,5–7 these individuals still have worse clinical outcomes, with higher rates of restenosis, stent thrombosis, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and death, when compared to non-diabetic subjects.8

Although some controlled clinical trials have demonstrated the superiority of second-generation DES compared to first-generation devices, particularly in reducing thrombosis,9,10 is not yet clear whether this benefit extends to unselected diabetic patients treated in daily practice.

The present study aimed to compare late clinical outcomes of minimally selected diabetic patients treated with first- vs. second- generation DES and included in the Drug-Eluting Stent In the REal world (DESIRE) Registry.

MethodsProtocol and study populationThe details of the protocol and the initial results of the (DESIRE) Registry have been reported.11 The DESIRE Registry is a prospective, non-randomized, single-arm study with consecutive inclusion of patients in treatment, performed at a single institution (Hospital do Coração, Associação do Sanatório Sírio) from São Paulo (SP), with the aim of investigating the long-term clinical outcome of patients treated with DES. Since May 2002, PCI with DES has been used as the strategy of choice for patients referred for routine or emergency percutaneous treatment in that institution. Patients with at least one lesion with stenosis > 50% and a favorable anatomy for PCI with stenting are included. By protocol, there are no limitations on the number of lesions and/or vessels that can be treated, and with respect to the number of DES implanted. The study is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the institution.

In this analysis, only diabetic patients, whether or not using insulin, and treated with first-generation sirolimus-eluting stents (SES, CypherTM, Cordis – Warren, USA) and second-generation everolimuseluting stents (EES, XIENCETM, Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, USA; or PromusTM, Boston Scientific – Natick, USA) were included. Only patients treated from January 2007 onwards (when there was a change in antiplatelet protocol at the institution) were included; all patients received acetylsalicylic acid and thienopyridines for at least 12 months following PCI.

ProcedurePCIs were performed according to current guidelines, and the final strategy of the procedure was left to the operators’ discretion. Implant of multiple stents and/or treatment of multiple lesions (for a staged or non-staged procedure) were also allowed.

The antithrombotic protocol consisted of the use of two antiplatelet agents: acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel. Pre-treatment with acetylsalicylic acid 200-500mg and clopidogrel 300mg was performed > 24hours prior to intervention for elective cases, or 600mg of clopidogrel > 2hours before the procedure for acute coronary syndrome without ST-segment elevation. After intervention, aspirin therapy was maintained indefinitely at a dose of 100-200mg/day; clopidogrel 75mg daily was maintained, starting from January 2007, during at least 12 months after PCI, according to recommendations of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). During the procedure, intravenous heparin was administered (70-100 U/kg) to maintain an activated clotting time > 250seconds (or > 200seconds in the case of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor administration). A 12-lead electrocardiogram was obtained before, immediately after and 24hours after the procedure. Laboratory tests included cardiac enzymes (creatine phosphokinase [CPK] and creatine phosphokinase fraction MB [CKMB mass]) before (< 24hours) and 18-24hours after the procedure, and afterwards on a daily basis in the case of change, until hospital discharge.

Objectives, definitions and clinical follow-upThe primary objective of the study was to compare the occurrence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) at late follow-up of diabetic patients treated with SES or EES. The combined endpoint of MACE included cardiac death, AMI, or ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization.

As a rule, all deaths were considered as of a cardiac origin, unless a non-cardiac cause could be clearly established by clinical and/or pathological study.

The diagnosis of AMI was based on the appearance of new pathological Q waves in at least two contiguous leads on an electrocardiogram and/or an elevation of CK-MB mass > 3-fold the upper limit of normal.

Stent thrombosis was defined according to the Academic Research Consortium (ARC) as definite, probable, or possible, and was also classified according to temporal occurrence, including acute (< 24hours from the procedure), subacute (between 24hours and 30 days), late (between 1 to 12 months), and very late (> 12 months) stent thrombosis.

Angiographic success was defined as a Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grade 3 final flow, no dissections, and residual stenosis < 20% by quantitative coronary angiography. A clinical follow-up was performed at 1, 6, and 12 months after the procedure, and then annually, consisting of scheduled medical visits or of telephone contacts, and conducted according to a pre-established protocol.

All reported adverse events, including stent thrombosis, were independently adjudicated by the Clinical Events Committee, including two experienced professionals in clinical and invasive cardiology.

Statistical analysisThe variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentages or means and standard deviations. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test and, when indicated, Fisher's exact test. Quantitative variables were compared using Student's t-test. The occurrence of adverse events with respect to time was described by Kaplan-Meier curves that were compared by log-rank test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Analyzes were performed with STATA statistical software, version 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, USA).

ResultsBasic clinical featuresBetween January of 2007 and October of 2014, a total of 3,856 patients were included in the DESIRE Registry. Of these, 1,280 (33.2%) were diabetic. Most of this population (62.3%) was treated with SES (n = 414) or EES (n = 384) and were included in the present analysis.

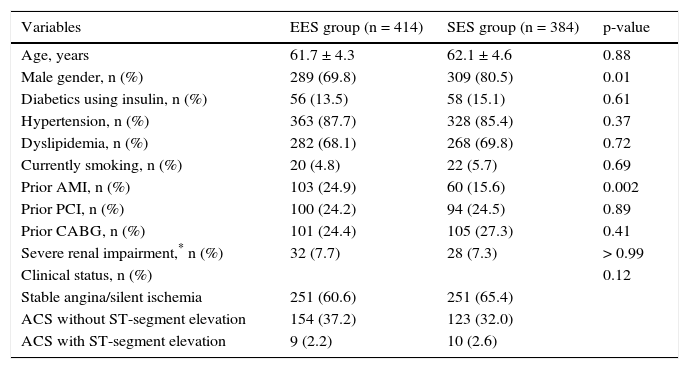

The mean age of the treated population did not differ (61.7 ± 4.3 years vs. 62.1 ± 4.6 years; p = 0.88), the majority were male, especially in the group treated with EES (69.8% vs. 80.5%; p = 0.01). The percentage of diabetics using insulin did not differ significantly between the two cohorts (13.5% vs. 15.1%; p = 0.61) and most of the population had a clinical presentation of stable coronary artery disease at the time of PCI (60.6% vs. 65.4%; p = 0.12). Table 1 shows the comparison among the main clinical variables in both groups.

Basal clinical characteristics.

| Variables | EES group (n = 414) | SES group (n = 384) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.7 ± 4.3 | 62.1 ± 4.6 | 0.88 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 289 (69.8) | 309 (80.5) | 0.01 |

| Diabetics using insulin, n (%) | 56 (13.5) | 58 (15.1) | 0.61 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 363 (87.7) | 328 (85.4) | 0.37 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 282 (68.1) | 268 (69.8) | 0.72 |

| Currently smoking, n (%) | 20 (4.8) | 22 (5.7) | 0.69 |

| Prior AMI, n (%) | 103 (24.9) | 60 (15.6) | 0.002 |

| Prior PCI, n (%) | 100 (24.2) | 94 (24.5) | 0.89 |

| Prior CABG, n (%) | 101 (24.4) | 105 (27.3) | 0.41 |

| Severe renal impairment,* n (%) | 32 (7.7) | 28 (7.3) | > 0.99 |

| Clinical status, n (%) | 0.12 | ||

| Stable angina/silent ischemia | 251 (60.6) | 251 (65.4) | |

| ACS without ST-segment elevation | 154 (37.2) | 123 (32.0) | |

| ACS with ST-segment elevation | 9 (2.2) | 10 (2.6) |

SES: sirolimus-eluting stent (first generation); EES: everolimus-eluting stent (second generation); AMI: acute myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; ACS: acute coronary syndrome.

*Creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min.

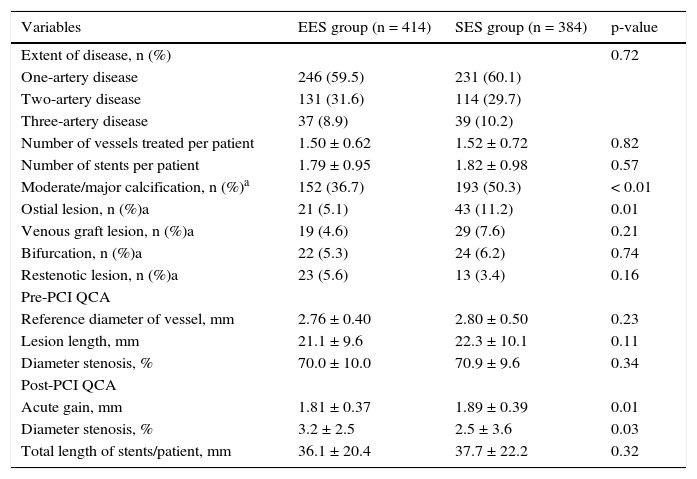

Approximately 40% of patients in both groups had multi-arterial disease, and a mean of 1.5 arteries/patient were treated, with no significant difference between cohorts. However, the population treated with EES presented more complex angiographic features, such as a higher percentage of moderate/severe calcified lesions (36.7% vs. 50.3%; p < 0.01) and ostial lesions (5.1% vs. 11.2%; p = 0.01).

The reference diameter (2.76 ± 0.4mm vs. 2.8 ± 0.5mm, p = 0.23) and the lesion length (21.1 ± 9.6mm vs. 22.3 ± 10.1mm; p = 0.11) did not differ between groups, but at the end of the procedure, higher acute gain and lower residual stenosis were observed among patients treated with EES. The total length of stents implanted per patient was 36.1 ± 20.4mm vs. 37.7 ± 22.2mm (p = 0.32). Table 2 details the major angiographic findings in both groups.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics.

| Variables | EES group (n = 414) | SES group (n = 384) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extent of disease, n (%) | 0.72 | ||

| One-artery disease | 246 (59.5) | 231 (60.1) | |

| Two-artery disease | 131 (31.6) | 114 (29.7) | |

| Three-artery disease | 37 (8.9) | 39 (10.2) | |

| Number of vessels treated per patient | 1.50 ± 0.62 | 1.52 ± 0.72 | 0.82 |

| Number of stents per patient | 1.79 ± 0.95 | 1.82 ± 0.98 | 0.57 |

| Moderate/major calcification, n (%)a | 152 (36.7) | 193 (50.3) | < 0.01 |

| Ostial lesion, n (%)a | 21 (5.1) | 43 (11.2) | 0.01 |

| Venous graft lesion, n (%)a | 19 (4.6) | 29 (7.6) | 0.21 |

| Bifurcation, n (%)a | 22 (5.3) | 24 (6.2) | 0.74 |

| Restenotic lesion, n (%)a | 23 (5.6) | 13 (3.4) | 0.16 |

| Pre-PCI QCA | |||

| Reference diameter of vessel, mm | 2.76 ± 0.40 | 2.80 ± 0.50 | 0.23 |

| Lesion length, mm | 21.1 ± 9.6 | 22.3 ± 10.1 | 0.11 |

| Diameter stenosis, % | 70.0 ± 10.0 | 70.9 ± 9.6 | 0.34 |

| Post-PCI QCA | |||

| Acute gain, mm | 1.81 ± 0.37 | 1.89 ± 0.39 | 0.01 |

| Diameter stenosis, % | 3.2 ± 2.5 | 2.5 ± 3.6 | 0.03 |

| Total length of stents/patient, mm | 36.1 ± 20.4 | 37.7 ± 22.2 | 0.32 |

SES: sirolimus-eluting stent (first generation); EES: everolimus-eluting stent (second generation); QCA: quantitative coronary angiography; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

aIndicates the presence of at least one lesion with the characteristic evaluated.

Clinical follow-up was obtained in 99.4% of patients.

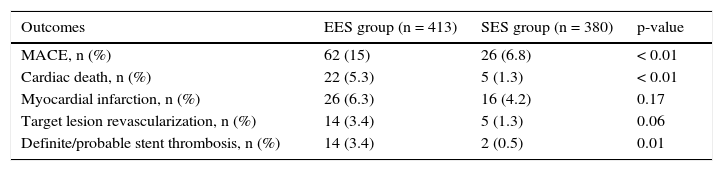

In general, patients treated with second-generation DES (EES) showed less adverse cardiac events, with less mortality (5.3% vs. 1.3%, p < 0.01) and tended to have a lower ischemia-driven targetlesion revascularization (3.4% vs. 1.3%, p = 0.06). A lower incidence of definite/probable thrombosis with the use of EES (3.4% vs. 0.5%; p = 0.01) was observed (Table 3).

Late clinical outcomes.

| Outcomes | EES group (n = 413) | SES group (n = 380) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE, n (%) | 62 (15) | 26 (6.8) | < 0.01 |

| Cardiac death, n (%) | 22 (5.3) | 5 (1.3) | < 0.01 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 26 (6.3) | 16 (4.2) | 0.17 |

| Target lesion revascularization, n (%) | 14 (3.4) | 5 (1.3) | 0.06 |

| Definite/probable stent thrombosis, n (%) | 14 (3.4) | 2 (0.5) | 0.01 |

EES: everolimus-eluting stent (second generation); SES: sirolimus-eluting stent (first generation); MACE: major adverse cardiac events.

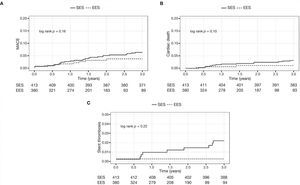

The Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence of MACE (panel A), cardiac death (panel B), and stent thrombosis (panel C) in both cohorts.

DiscussionThe main finding of this study is the fact that the second-generation EES demonstrated better efficacy and safety profile in the treatment of diabetic patients in daily practice, with lower cardiac mortality and stent thrombosis compared to first-generation SES.

Diabetic patients tend to have a more exacerbated healing response, with neointimal overgrowth after treatment with PCI, a fact associated with higher restenosis rates in this population.12

Since preliminary studies, first-generation DES with sirolimus or paclitaxel, due to their high antiproliferative power, demonstrated superiority vs. bare metal stents in reducing in-stent lumen loss and hence the need for repeat revascularization procedures among diabetic patients.

The onset of second-generation DES potentially would further improve these results, especially when using EES. Studies in populations including diabetic and nondiabetic subjects showed superiority of these stents vs. first-generation DES with paclitaxel, reducing thrombosis, target lesion revascularization, and even mortality.9,10

However, when comparing EES versus first-generation SES, especially in diabetics, the results are not always consistent. In two randomized clinical trials, ESSENCE-DIABETES13 and SORT-OUT IV14 studies, it was demonstrated that EES was only non-inferior to SES in the treatment of patients with diabetes mellitus. In common, both studies showed a relatively short period of follow-up (12 and 18 months, respectively); this may have been insufficient to detect differences between these devices, since, as seen in this analysis, they tend to occur especially after the sixth month and continue to occur later.

Corroborating this hypothesis, recent meta-analysis published by Yan et al. including approximately 1,500 patients with diabetes mellitus coming from ten controlled clinical trials, some of them with a long-term follow-up (> 2 years), demonstrated that the use of EES reduced mortality (RR = 0.58; 95%CI: 0.37-0.90; p = 0.01) and thrombosis (RR = 0.46; 95%CI: 0.22-0.95, p = 0.03) rates, when compared to first-generation DES with paclitaxel or sirolimus.15 These results are perfectly aligned with the findings of the present study, probably justified by the longer follow-up of Yan et al., particularly at a stage that dual antiplatelet therapy has been already discontinued for most individuals.

LimitationsThis study has some limitations that must be observed. First, it is a non-randomized analysis. Moreover, although it is the largest Brazilian cohort study comparing these two DES in diabetic patients, the numbers are still relatively small to permit more definite conclusions. Finally, this represents the experience of a sole institution.

ConclusionsIn this one-center experience, the use of second-generation EES in unselected diabetic patients was effective and safe, with lower rates of cardiac mortality and stent thrombosis when compared to first-generation SES. This benefit was seen mainly in late follow-up.

Funding sourcesNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.