Dysphagia has a high prevalence with associated complications, such as respiratory infections and recurrent institutionalizations, factors associated with the burden of malnutrition and dehydration that negatively affects the patient's quality of life and entails added health costs.

ObjectiveTo assess the knowledge of a group of Portuguese nurses regarding dysphagia and perform the cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaire used.

MethodsCross-sectional descriptive study based on an online self-ministered questionnaire sent to nurses, regardless of the length of professional experience and area of clinical practice. Data treatment was performed using the IMB SPSS computer software, and the open responses were treated using the QDA Miner Lite.

Results241 nurses were enrolled between May and June 2021, of which 192 (79.6%) were female, with an age of 37.8±8.3 years and a length of service of 14.4±8.5 years. Overall knowledge of dysphagia was high (80.1%). Participants were dissatisfied with their knowledge and expressed a need for further training, mainly in therapeutic intervention.

ConclusionsIt is essential to understand why nurses still consider themselves to lack knowledge despite higher levels of knowledge. Future research should explore these aspects. These findings corroborate the gap between the nurses’ perceived knowledge and their actual knowledge about dysphagia, which may influence practice by influencing the decision-making process. Due to its high prevalence and complications, this gap may translate into increased patient safety risks.

La disfagia tiene una alta prevalencia, con complicaciones asociadas, como infecciones respiratorias e ingresos hospitalarios recurrentes, factores asociados a la carga de desnutrición y de deshidratación, aspectos que afectan negativamente a la calidad de vida del paciente y suponen un coste sanitario añadido.

ObjetivoEvaluar los conocimientos de un grupo de enfermeros portugueses sobre la disfagia y realizar la adaptación cultural del instrumento utilizado.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo transversal basado en un cuestionario autoadministrado online enviado a los enfermeros, independientemente del tiempo de experiencia profesional y del área de práctica clínica. El tratamiento de los datos se realizó con el programa informático SPSS IMB, y las respuestas abiertas se trataron con el QDA Miner Lite.

ResultadosEntre mayo y junio de 2021 se inscribieron 241 enfermeros, de los cuales 192 (79,6%) eran mujeres, con una edad de 37,8±8,3 años y una antigüedad de 14,4±8,5 años. El conocimiento general de la disfagia era alto (80,1%). Los participantes se mostraron insatisfechos con sus conocimientos y expresaron la necesidad de una mayor formación, principalmente en materia de intervención terapéutica.

ConclusionesEs esencial comprender por qué las enfermeras siguen considerando que carecen de conocimientos a pesar de tener niveles más altos. Las investigaciones futuras deberían explorar dichos aspectos. Estos hallazgos corroboran la brecha existente entre los conocimientos percibidos por las enfermeras y sus conocimientos reales sobre la disfagia, lo que puede influir en la práctica al intervenir en el proceso de toma de decisiones. Debido a su elevada prevalencia y a sus complicaciones, esta brecha puede traducirse en un mayor riesgo para la seguridad del paciente.

The swallowing process is essential for the maintenance of life, allowing not only the transport of food from its ingestion to the stomach, initiating the digestion process and promoting the elimination of saliva from the oral cavity, but also preventing its passage to the airways, having a protective component.1,2 Swallowing thus emerges as a vital function whose role of protection and nourishment underlies the survival of each individual. On the other hand, dysphagia is considered a swallowing dysfunction. Depending on the affected swallowing phase, dysphagia can be classified as oesophagal or oropharyngeal (the most frequent).3

Dysphagia is defined as difficulty in swallowing, forming, or moving the food bolus safely or effectively between the oral cavity and the oesophagus, resulting in penetration/aspiration into the airways, a delay in the duration of the bolus flow, or the existence of post-swallowing residue in the pharyngeal cavity. It is considered an emerging pandemic among the elderly in the 21st century, revealing its proper management as one of the biggest challenges for the health system and healthcare providers.2,3

Most diseases that cause dysphagia are more prevalent with advancing age, aggravated by the physiological changes of ageing (presbyphagia). Dysphagia is often a cause of severe suffering due to the high risk of aspiration, which can lead to aspiration pneumonia, reduced food and fluid intake, with consequent malnutrition and dehydration, and therefore, reduced quality of life and increased risk of mortality. Dysphagia increases morbidity and mortality and significantly affects patients’ quality of life by turning mealtimes into a distressing and stressful time for themselves and their families.1,4,5

Hereupon, the terms swallowing and dysphagia appear inseparable and closely linked to the activities developed by nurses in patient care. Their role involves screening and proper referral in situations of positive screening, as well as adopting strategies integrated into a multidisciplinary team care planning that prevent complications in terms of nutrition and oral hygiene.6 Nurses, therefore, play a crucial role in supporting patients with swallowing problems. Given that nurses are the health professionals who spend the most time with dysphagic inpatients, training them to assess and recognize dysphagia is necessary to increase patients’ safety. Knowledge about swallowing disorders helps nurses to identify the problem in time and refer these patients for diagnosis and treatment to the care of specialized health professionals. When nurses identify dysphagia within the first 24h after admission, they can reduce the patient's time deprived of adequate nutrition and hydration, which increases the likelihood of better clinical outcomes, and is reflected in health gains.7,8

Despite the high prevalence, dysphagia is not systematically screened or adequately addressed; it is mostly silent and often goes unnoticed by healthcare providers. It is, therefore, crucial to perform an early screening that is adequate and timely to minimize complications, adjust interventions, improve the quality of life and enhance patients’ functionality. Nurses’ knowledge is paramount to ensuring this adequate and timely assessment.1,8

The problem of dysphagia has gained relevance over the last few years in the scientific field of nursing, as it is commonly forgotten or overlooked from a clinical point of view.9–11 Nurses’ knowledge, practices, and attitudes in the therapeutic approach to the patient with dysphagia fall short of the best practice, which can have negative consequences for the patient, family, and society in general, with increased health costs.6,9–12

In this context, a study was developed to assess nurses’ knowledge regarding symptoms, complications, and management of dysphagia and their overall knowledge level. As a secondary objective, the cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaire used in this study was performed.

MethodsA descriptive cross-sectional design was developed using an anonymous self-administered questionnaire for nurses working in any clinical context, using a non-probabilistic convenience sampling technique. The questionnaire was sent to all nurses with a registered email in a Health School database, between May and June 2021, irrespective of the length of professional experience and area of clinical practice. This database comprises nurses that obtained their degree or specialization in this school. Informed consent was presented on the first page of the questionnaire, and participants only had access to the remaining questionnaire after explicit consent.

The questionnaire used by Rhoda and Pickel-Voight10 was translated and adapted to comply with the study aim, following the guidelines of Wild et al.,13 with the authors’ authorization. The translation was performed by two independent Portuguese native translators and consensualized by the researchers. The back translation was performed by a native English translator. The face and content validity of the original version was obtained through an expert panel, and reliability (test–retest) yielded intra class correlation results >0.7.10 In the adaptation process, sociodemographic questions were adjusted to the Portuguese context. The questions with explicit reference to stroke patients with dysphagia were altered to dysphagic patients, in general, to comply with the study's aim. To ensure the face and content validity of the Portuguese version, three experts with more than 10 years of working experience in this field (two rehabilitation nurses and a researcher) reviewed the instrument and determined that it satisfactorily covered the aspects to be measured.

After the translation and adaptation of the original questionnaire to the European Portuguese language, a cognitive debriefing was carried out with five nurses who met the inclusion criteria and thus understood if, after translation and adaptation, the questionnaire was intelligible within the clinical nursing context. All nurses invited to participate in the cognitive debriefing had more than 10 years of working experience with patients with dysphagia. The questionnaire consisted of five parts. The first comprised data collection for the sociodemographic characterization of the participants. The second, third, and fourth parts comprised, respectively: 13, nine, and seven questions, of closed-response, with three options (agree, unable to decide, and disagree), about signs and symptoms, complications and management of dysphagia; the fifth part comprised four closed-response questions (yes, no or I am not sure) about previous experience in caring for patients with dysphagia, satisfaction with the level of knowledge and previous training and one open-ended question where participants were asked to identify the areas in which they would like to have more training. Questions were scored 1 point when correctly answered, and no score was assigned to questions with a wrong answer or whose answer was “unable to decide”. The maximum possible score is 30 points, representing the highest knowledge level. Scores lower than 50% of the maximum possible value represent low knowledge, between 50 and 75% moderate, and greater than or equal to 75% high.10

According to the nature of the data, they were processed using SPSS, version 23, and QDA Miner Lite. Quantitative data were subjected to descriptive and inferential statistics using a t-Student test to search for differences between groups for a 95% confidence interval. Qualitative data were analyzed, starting with a first coding followed by a list of codes that later evolved into focused coding and subsequent categorization and sub-categorization. For reliability, internal consistency of the items was calculated using Cronbach's alpha. No power analysis was conducted.

This study was authorized by the Ethics Committee of the Portuguese Red Cross Northern Health School (No. 010/2021). Preceding the questionnaire was an informed consent form, which included the purpose of the study, confidentiality safeguards, and a statement on the voluntary nature of participation. Participants would only have access to the questionnaire after explicitly giving their consent to participate in the study. The questionnaire did not ask for any data that could identify the participant, and participants were asked not to write on the questionnaire any information that would allow them to be identified. Participants’ data were treated with confidentiality.

ResultsA total of 2664 questionnaires were sent via email (single email), and 241 valid responses were obtained. Regarding the sociodemographic and professional characterization of the 241 participants, the mean age was 37.8±8.3 years, ranging between 21 and 61 years, and the majority (n=192; 79.6%) were female. As for the professional title, 63.9% of the participants (n=154) had the title of registered nurse, and 36.1% (n=87) had the title of specialist nurse. Regarding academic qualifications, 84.6% (n=204) of the participants were graduates, 13.3% (n=32) had a Master's degree and 2.1% (n=5) were PhDs. Length of service varied between 0 and 39 years, with a mean of 14.4±8.5 years. The median length of service was 14 years and an interquartile range of 9. Most participants were in direct care provision (n=219; 90.9%), 7.5% (n=18) in management, and 1.7% (n=4) in teaching. Participants in direct care provision worked in the following areas: medical wards (n=87; 39.7%), emergency room (n=42; 19.2%), outpatient care (n=27; 12.3%), surgical wards (n=25; 11.4%), intensive care unit (n=14; 6,4%), paediatrics and maternal health (n=14; 6.4%), and mental health (n=10; 4.6%). The internal consistency is moderate but acceptable (α=0.65).

For the participants’ knowledge of signs and symptoms of dysphagia (Table 1), the question with more correct answers was “Cough while eating” with 96.3% (n=232). The one with the least correct answers was “Chest pain” with 33.6% (n=81) of the participants not agreeing that chest pain is a dysphagia symptom. Of the 13 questions, the mean of correct answers by the participants was 9.3, expressing a moderate knowledge level (71.5%).

Knowledge of signs and symptoms of dysphagia.

| Variables | Correct answers (n/%) |

|---|---|

| Cough while eating | 232/96.3 |

| Skin irritations | 189/78.4 |

| The sensation of food stuck in the throat | 227/94.2 |

| Choking on saliva outside of meals | 228/94.6 |

| Poor tongue movements | 196/81.3 |

| Food residues in the mouth | 191/79.3 |

| Difficulty chewing | 170/70.5 |

| Patients constantly cough when they aspirate | 152/63.1 |

| Difficulty closing the lips | 113/46.9 |

| Weight loss | 143/59.3 |

| Clearing the throat frequently after swallowing | 190/78.9 |

| Hoarse voice | 131/54.4 |

| Chest pain | 81/33.6 |

Concerning knowledge of dysphagia complications (Table 2), the question correctly answered by more participants was “Aspiration” (n=240; 99.6%), and the one with lesser correct answers was “Haematemesis” (n=141; 58.5%). From the ten questions, the participants’ mean of correct answers was 8.1, representing a high level of knowledge (81.0%).

Knowledge of dysphagia complications.

| Variables | Correct answers (n/%) |

|---|---|

| Increased mortality | 198/82.2 |

| Pneumonia | 236/97.9 |

| Anaphylactic shock | 179/74.3 |

| Generalized weakness | 188/78.0 |

| Problems with digestion | 165/68.5 |

| Aspiration | 240/99.6 |

| Dehydration | 222/92.1 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 162/67.2 |

| Malnutrition | 228/94.6 |

| Haematemesis | 141/58.5 |

Regarding the knowledge of dysphagia management (Table 3), two questions had the highest number of correct answers: “Tube-fed patients need daily oral care” and”the best position to feed a patient is in the supine position” (n=240; 99.6%). The question with the least number of correct answers was “Non-thickened liquids are the safest substances to drink” (n=211; 87.6%). From the seven questions, each participant scored a mean of 6.6 correct answers, resulting in a level of knowledge about dysphagia management of 94.3%.

Knowledge of dysphagia management.

| Variables | Correct answers (n/%) |

|---|---|

| Tube-fed patients need daily oral care | 240/99.6 |

| Thickened liquids must be avoided | 216/89.6 |

| Unthickened liquids are safe to drink | 211/87.6 |

| All patients with swallowing disorders need a feeding tube | 228/94.6 |

| The best position to feed a patient is in the supine position | 240/99.6 |

| Patients can always eat regular hospital food | 232/96.3 |

| A feeding tube is only indicated in patients with impaired consciousness | 220/91.3 |

The overall knowledge level of participants was 80.1%, with a mean of correct answers of 24.0 ± 3.25, ranging from 13 to 30, classified as high.

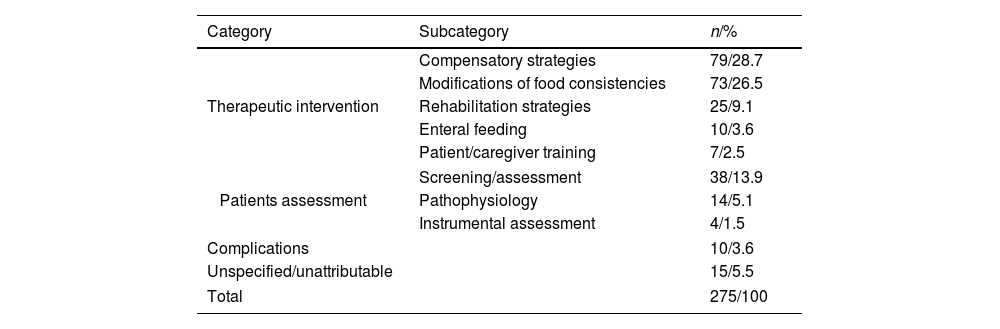

Regarding the experience with patients with dysphagia, 95.9% (n=231) of the participants had previous experience with patients with swallowing disorders, 52.3% (n=138) never received training on care for patients with dysphagia, and 61.8% (n=149) were dissatisfied with their knowledge in this field. Most participants (n=186;78.2%) expressed interest in receiving additional education/training on treating patients with dysphagia. The participants’ answers regarding their training needs were analyzed and organized by categories and subcategories (Table 4). Four categories emerged with associated subcategories: Therapeutic intervention, Patients’ assessment, Complications, and Unspecified/unattributable.

Coding frequency for categories and subcategories on training needs.

| Category | Subcategory | n/% |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic intervention | Compensatory strategies | 79/28.7 |

| Modifications of food consistencies | 73/26.5 | |

| Rehabilitation strategies | 25/9.1 | |

| Enteral feeding | 10/3.6 | |

| Patient/caregiver training | 7/2.5 | |

| Patients assessment | Screening/assessment | 38/13.9 |

| Pathophysiology | 14/5.1 | |

| Instrumental assessment | 4/1.5 | |

| Complications | 10/3.6 | |

| Unspecified/unattributable | 15/5.5 | |

| Total | 275/100 | |

The category Therapeutic intervention was based on the training needs presented about the nurse's role as a care provider to the patient and family/caregiver. Patients’ assessment category included the subcategories related to Screening/assessment, Instrumental assessment, and Pathophysiology associated with dysphagia. In the categories Complications and Unspecified/unattributable, no subcategories were identified. This last category comprised expressions that were impossible to include in any categories/subcategories previously identified (Table 5).

Participants’ quotes examples for each category/subcategory.

| Category | Subcategory | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic intervention | Compensatory strategies | “positioning to avoid aspiration” (Participant [P]42)“compensatory manoeuvres” (P132)“strategies to adopt for safe feeding” (P215) |

| Modifications of food consistencies | “type of food consistency, type of consistency in thickened liquids” (P14);“cautions to be taken when using the thickener” (P210);“what is the best thickness/consistency of foods appropriate for patients with dysphagia” (P246) | |

| Rehabilitation strategies | “rehabilitation of the person with dysphagia” (P17);“muscle training to strengthen swallowing muscles” (P119) | |

| Enteral feeding | ”management of the moment to introduce the feeding tube” (P49);“care management of patients with Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy” (P69) | |

| Patient/caregiver training | “Education for the home care” (P105);“education to caregivers” (P240);“Education for the patient and family” (P245) | |

| Patients’ assessment | Screening/assessment | “Assessment of dysphagia according to different assessment instruments” (P52);“how to test for dysphagia” (P30), |

| Pathophysiology | “causes of dysphagia” (P117);“diseases associated with dysphagia” (P123) | |

| Instrumental assessment | “swallowing videofluoroscopy technique” (P194) | |

| Complications | “dysphagia complications” (P101);“intervention in the face of complications” (P48) | |

| Unspecified/unattributable | “everything” (P77);“all subjects related to the questions asked” (P230); “because we always have something to learn …” (P72) | |

Differences in knowledge were searched between registered nurses and specialist nurses using the t-Student test. The knowledge level of registered nurses was 78.6%, with a mean score of 23.6±3.3, and that of specialist nurses was 83.0%, with a mean score of 24.9±2.9. For a significance level of 0.05, there are statistically significant differences between these two groups, with the knowledge being significantly higher in specialist nurses than in registered nurses, with t=−3.03, P=.003. Comparing participants with previous training with nurses with no prior training, the knowledge level of participants with training was 83.0%, with a mean score of 24.9, and that of nurses with no training was 78.0%%, with a mean score of 23.4. The differences between the two groups were also statistically significant (t=−3.65; P<.000).

DiscussionThis study explored nurses’ knowledge on dysphagia signs and symptoms, complications and management. With the use of a face validity procedure and reliability using Cronbach's alpha, a Portuguese version was obtained. Participants express dissatisfaction with their knowledge and declare interest in receiving additional training. Similar results were obtained in other studies assessing nurses’ knowledge of dysphagia.9,14 The difference between the participants’ knowledge, dissatisfaction with their knowledge of dysphagia, and willingness to receive additional training could indicate the need to reinforce or consolidate that knowledge or the need for nurses to be updated in training over time due to the risk of doubting their knowledge. Training has a positive impact on nurses’ knowledge and skills.15

A higher level of knowledge was found compared with previous studies that used the same questionnaire: 80.1% vs 62.39% in the study by Nepal and Sherpa9; 57.34% in the study by Rhoda and Pickel-Voight10 and 57.33% in the study by Knight et al.14 Even with a perceived lack of training, and a desire for more training, participants show high levels of knowledge. Comparing participants in the different studies, in the study by Nepal and Sherpa,9 all participants worked in a tertiary hospital, and of those, 50% worked in medical wards. In the study by Rhoda and Pickel-Voight,10 all participants worked in a hospital, and working places were more diverse. The most representative group of participants in this study were nurses working in medical wards (n=39; 21.1%). In the study by Knight et al.,14 most participants (n=86; 66.2%) worked in medical wards. The heterogeneity of the participants’ workplaces hinders comparison; however, training and cultural differences may explain this apparent contradiction.16,17 A significant variation is recognized in the quality and level of training of nurses around the world.18

In a more detailed analysis of results on knowledge of sing and symptoms, despite most participants correctly identifying swallowing difficulty with coughing while eating, evidence shows that not all patients with swallowing disorders, especially aspiration, cough overtly.19 A high percentage of participants (36.9%) considered that patients always cough when they aspire, revealing a lack of awareness of silent aspiration, a recognized indicator of dysphagia.20 In the study by Rhoda and Pickel-Voight,10 fewer participants responded incorrectly to this question (19.5%). Still, in findings by Nepal and Sherpa,9 most participants responded that coughing is always present during aspiration (78.3%) and Knight et al.14 (94.6%). If not correctly identified, silent aspiration puts the patient at risk for aspiration pneumonia.21

Regarding dysphagia complications, aspiration was the complication identified by most participants (99.6%), corroborating other findings.9,10,14 Pneumonia was also correctly identified by participants. Evidence shows that dysphagia increases more than 4-fold the risk of aspiration pneumonia22 and is a critical factor in aspiration pneumonia. Pneumonia foresees worse functional outcomes and increases the length of stay and mortality risk.23 In this context, it is essential to note that pneumonia is multifactorial and cannot be exclusively attributed to dysphagia.24

Analyzing the questions in the section on dysphagia management, participants scored the highest number of correct answers (94.3%), contrary to previous studies that revealed low10 to moderate9,14 levels of knowledge. These results are particularly relevant considering that nurses play a crucial role in care provision to inpatients, assisting patients with eating and drinking, administering medication orally, and educating patients with dysphagia and their caregivers on diet preparation and safe feeding.25

It should be noted that most participants know the value of using thickening agents in patients with dysphagia. Although they do not improve swallowing physiology, different international guidelines recommend using thickeners.6,26 However, the use of thickeners is associated with an increased risk of dehydration, higher incidence of silent aspiration due to post-swallowing residues, and worse quality of life,26,27 the reason for which these guidelines also recommend that hydration status in these patients must be carefully monitored.

Results revealed that specialist nurses presented a significantly higher knowledge level than registered nurses. A similar result was found by Rhoda and Pickel-Voight,10 in which nurses with higher training and qualification had a significantly higher level of knowledge on dysphagia symptoms, complications, and management. Available evidence suggests that nurses’ caring for patients with dysphagia value training and recognize the need to improve their skills and knowledge in this field.25,28

Still concerning training needs, paradoxically in terms of knowledge, participants identified more significant training needs in dysphagia management. Previous studies identified the lowest levels of knowledge.9,10 These results suggest that the participants attribute greater relevance to the implementation of nursing care compared to aspects related to the conceptualization of care, in line with the previous findings.25 Gaps between actual and perceived knowledge have been previously identified among nurses17 and multiple factors influence the nursing knowledge-practice gap.29 The consequences of these gaps may influence how nurses practice, regardless of their training or qualifications, by influencing the decision-making process16 and should be addressed in research.

Dysphagia management requires a multidisciplinary approach to respond to patients’ needs. Nurses and speech-language therapists (SLT) play a key role in caring for patients with dysphagia, especially those with aspiration precautions or modified diets.30

Results show a low response rate and a small sample size. Although easier to distribute and lower costs, online questionnaires may entail a selection bias that can compromise the results. A single email sending was made, but evidence suggests that more effective strategies can increase the response rate, such as email pre-notification, email invitation, two reminders, and a semi-automatic log-in.31 A single email sending may have limited the response rate. One of this study's limitations may have resulted from a response bias, where only the nurses most interested in the topic responded. Another limitation may have been the lack of inclusion criteria. Nurses with no contact/previous experience with patients prone to dysphagia could respond.

ConclusionsThe present study showed that participants had a high level of knowledge regarding dysphagia, although revealing the need for training, with predominance for training on dysphagia management. Multiple factors influence the knowledge-practice gap in nursing; understanding these factors is of utmost importance in narrowing this gap. Qualifications emerge as a factor that correlates with the level of knowledge, with higher knowledge levels being associated with higher qualifications. Therefore, training gaps must be identified and addressed. Multidisciplinary collaboration between nurses and SLT may improve nurses’ knowledge in identifying and managing dysphagic patients. Researchers should implement strategies that promote increased response rates as online questionnaires are expanding significantly.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors would like to thank all the nurses who participated in this study for their collaboration.