To evaluate the effectiveness of virtual reality on the degree of Health Literacy, before and after the use of virtual reality with the Nintento Switch® device in patients with a diagnosis of stroke admitted to neurorehabilitation units.

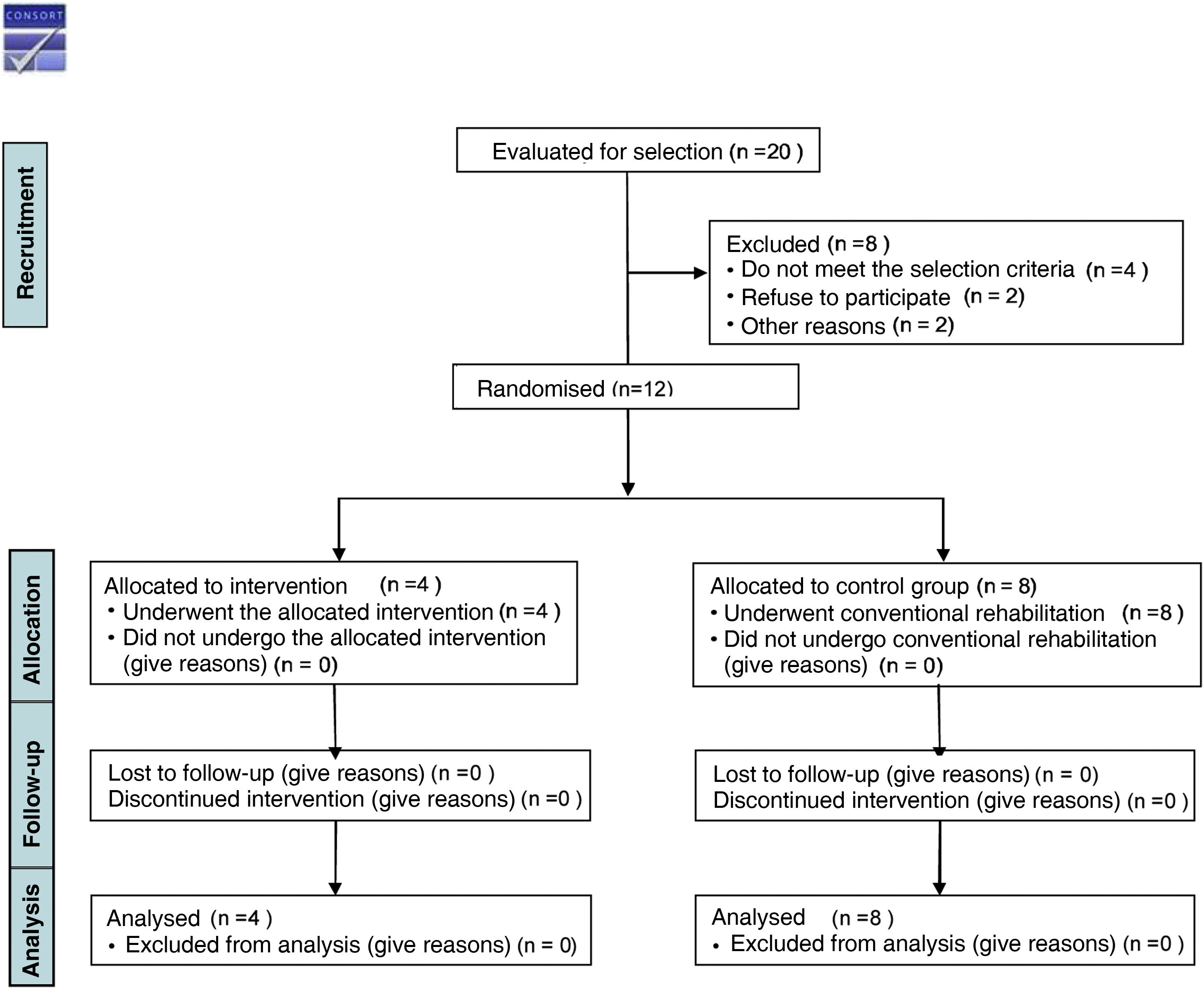

MethodologyTwelve patients admitted to a neurorehabilitation unit underwent a 1:3 randomised clinical trial (intervention group: control group). The intervention group consisted of 4 patients and the control group consisted of 8 patients. The control group performed conventional rehabilitation and the intervention group, in addition to conventional rehabilitation, had a 20-min virtual reality intervention once a week for 6 weeks. Clinical outcomes were measured for the literacy variable before the intervention and 6 weeks after the intervention in both the control group and the intervention group.

ResultsAn improvement in literacy was obtained in the control group (9 vs. 9.38; p = 0.18) and in the intervention group (13.75 vs. 14.25; p = 0.31) after the 6 weeks duration of the study. Comparing the intervention group and the control group, the literacy level of the intervention group was higher after the intervention than in the CG (14.25 vs. 9.38: p = 0.20), but no statistically significant results were obtained.

ConclusionVirtual reality used together with conventional treatment seems to improve the degree of literacy of stroke patients admitted to neurorehabilitation units.

Evaluar la efectividad de la realidad virtual en el grado de Alfabetización en Salud, antes y después del uso de la realidad virtual con el dispositivo Nintento Switch® en pacientes con diagnóstico de Ictus ingresados en unidades de neurorrehabilitación.

MetodologíaDoce pacientes ingresados en una unidad de neurorrehabilitación fueron sometidos a un ensayo clínico aleatorizado 1:3 (grupo intervención: grupo control). El grupo intervención estuvo formado por 4 pacientes y el grupo control por 8 pacientes. El grupo control realizó la rehabilitación convencional y el grupo intervención, además de la rehabilitación convencional, tuvo una intervención de 20 minutos de realidad virtual una vez a la semana durante 6 semanas. Se midieron los resultados clínicos para la variable alfabetización antes de la intervención y seis semanas después de la intervención, tanto en el grupo control, como en el grupo intervención.

ResultadosSe obtuvo una mejoría en el grado de alfabetización del grupo control (9 vs. 9,38; p = 0,18) y en el grupo intervención (13,75 vs. 14,25; p = 0,31) tras las 6 semanas de duración del estudio. Comparando el grupo intervención y el grupo control, el nivel de alfabetización del grupo intervención fue mayor tras la intervención que en el GC (14,25 vs. 9,38: p = 0,20), no se obtuvieron resultados estadísticamente significativos

ConclusiónLa realidad virtual utilizada junto con el tratamiento convencional, no parece mejorar el grado de alfabetización de los pacientes con ictus ingresados en unidades de neurorrehabilitación.

Stroke is a neurological disease in which brain tissue is damaged due to a sudden rupture or embolism of a blood vessel, serious complications such as depression can result.1 It is the leading cause of disability and the second leading cause of death worldwide.2,3 It is an important public health problem of high incidence and prevalence associated with high morbidity and mortality.1,2 Data published by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (INE) in 2022 reveal a total of 24,558 deaths caused by stroke in Spain.4

Patients who have suffered a stroke have a number of physical, cognitive, sensory, language, and visual limitations. Movement disorders can limit muscle control, movement and balance functions. Often these patients present with hemiplegia, which manifests as postural instability, asymmetrical weight bearing, impaired transfer abilities, and decreased postural stability, limiting basic activities of daily living (ADLs) and therefore causing self-care deficits.5,6

A systematic review published in Cochrane (2016) indicates that developing self-care skills can help to reduce stroke sequelae and, therefore, improve quality of life.7 However, different studies highlight that there are often great emotional difficulties following a stroke that have a direct impact on the outcome of rehabilitation and self-care.6

Establishing the health literacy (HL) of patients/users is currently the cornerstone in our provision of holistic care, based on individual needs and thus fostering patient empowerment. This care is in line with the Spanish Ministry of Health's strategy for tackling chronicity, which takes a person-centred approach, guaranteeing continuity of care and personal autonomy. Thus, objectives 3 and 20 of this strategy promote health literacy as a tool to ensure equity and efficiency in the care of patients with chronic diseases.8

The term HL was first coined in 1974 by Professor Scott K. Simonds during a conference on education and health.9

In 1998, the WHO then added the concept to its glossary stating that ‘Health Literacy has been defined as the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health’.10 Since then, many definitions have been given in the literature; Sorensen et al. propose a definition that attempts to bring together up to 17 of them, stating that ‘Health literacy is linked to literacy and entails people's knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information in order to make judgments and take decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course’.11

In this regard, there are studies that establish a relationship between the degree of HL and self-care, adherence to treatment, hospital readmissions, quality of life, and morbidity/mortality. A 2017 study by Hahn et al. states that an adequate degree of health literacy improves the quality of life of these patients, empowering them to make better decisions in relation to their rehabilitation.12

Although we found no studies that analyse how virtual reality (VR) relates to the level of HL in stroke patients, there are projects in other populations that claim that VR therapies improve levels of HL.13

Because there are so few articles that study the influence of VR on HL, we set out in this study to analyse this relationship in stroke patients.

This randomised clinical trial (RCT) aims to evaluate the effectiveness of VR on the degree of HL before and after use of virtual reality with the Nintendo Switch® device (Nintendo Platform Technology, Japan) in patients diagnosed with stroke admitted to neurorehabilitation units.

Material and methodWe conducted a randomised controlled clinical trial to compare whether literacy improved in the intervention group (IG) after using VR in stroke inpatients compared to a control group (CG).

We used the CONSORT 2010 statement for randomised clinical trials.14

Patients were recruited from October 2021 to January 2022 at the Centro Estatal de Atención al Daño Cerebral (CEADAC), in Madrid. This is a public social-health centre where patients with acquired brain injury undergo individualised rehabilitation delivered by a multidisciplinary team.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) patients of legal age admitted with stroke; (2) command of oral and written Spanish; (3) preserved cognitive functions of expression and comprehension according to Mississippi Aphasia Screening Test15 (MAST); (4) mobility of at least one upper limb; (5) patients able to sit.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) inpatients with diagnosed psychiatric illness; (2) patients with visual loss that precluded the use of VR.

Twenty patients were recruited, of which only 12 met the inclusion criteria for participation in the pilot study. The patients had to have been admitted for at least 15 days in order to participate in the study, so that they would have become familiarised with the centre and its dynamics.

Details of the flow chart of the study procedure can be found in Fig. 1.

All patients admitted to the neurorehabilitation unit were summoned to a room where they were given all the information on the objectives of the study and the methodology to be followed. Patients who wished to take part in the study were randomised and allocated to a group and were provided with the patient information sheet together with the informed consent form.

Software was used to allocate the patients (Excel 2021 18.0, Microsoft) with a ratio of 1:3 (IG:GC).

Neither the patients nor the investigator conducting the intervention could be blinded to the intervention due to its nature. Data analysis was performed by an investigator who was not involved in the randomisation of the patients.

The sample size was calculated considering the data provided by the admissions service of CEADAC in the period 2018/2019, when they had admitted 13 patients, and using the estimation of proportions formula, taking a confidence level of 95%, a precision of 3%, a margin of error of .05, and a 10% loss of patient data to be excluded from the study; the required sample size was 12 patients. The sample size used in other pilot studies with virtual reality and stroke patients was also taken into account.16,17

InterventionThe CG and IG patients underwent conventional rehabilitation consisting of 600 min per week of individualised physiotherapy, 120 min per week of speech therapy, and 30–60-minute sessions of neuropsychology.

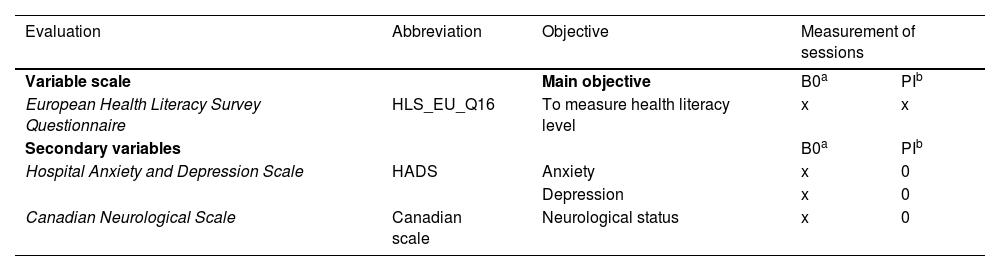

The IG, in addition to conventional rehabilitation, underwent six 30-minute VR sessions once a week (Table 1).

Description of the intervention based on Clinicals.gov Checklist.

| Item | IG a | CG b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Name | VRc+CRd | CRd |

| 2 | Reason | Both interventions were compared in stroke patients to demonstrate that virtual reality-based technology improves health literacy in stroke patients. If so, it could be implemented as an adjuvant therapy in specialist neurorehabilitation units | |

| 3 | Organisation | A briefing session was held with both groups to explain what the study consisted of and what the rehabilitation of the GI and CG would involve. In addition, participants who freely agreed to participate in the study signed the informed consent form and the patient information sheetCompletion of information through reading medical recordsCompletion of tests shown in Table 2 | |

| 4 | Randomisation | Through computer software | |

| 5 | Description of groups | Session 1: brief explanation of use of the deviceIG: once weekly transfer to the VR room in addition to conventional rehabilitation | Conventional rehabilitation |

| 6 | Time periods | The VR intervention lasted 20 min, once a week, for six weeksConventional therapy was delivered daily, and each individual patient given a time | Conventional therapy was delivered daily, and each individual patient given a time |

| 7 | Study participants | Baseline: 4 participantsCompletion: all the participants completed the study. | Baseline: 8 participantsCompletion: all the participants completed the study |

The VR sessions were performed with the Nintendo Switch® device and were conducted by a nurse with experience in neurorehabilitation units who accompanied the patients during all sessions in case of any technical problems.

VariablesThe data collected from the medical records were age, sex, type of stroke, main caregiver, degree of stroke damage, time since stroke, patients with hypertension and patients with dyslipidaemia. Data from the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS18 and the Canadian Neurological Scale19 were collected at the start of the study by means of a personal interview.

The HADS scale is a questionnaire consisting of 14 questions, of which seven refer to the anxiety subscale (odd-numbered questions) and seven to the depression subscale (even-numbered questions). Each question has scores ranging from ‘0’ to ‘3’, with a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 21 for each subscale. Scores of ‘0’ to ‘7’ imply no symptoms, ‘8’ to ‘10’ mild symptoms, and from ‘11’ to ‘21’, considerable anxiety and/or depression symptoms.18

The Canadian Neurological Scale assesses mental status (consciousness, orientation, and language) and motor function (face, arms, and legs, adapted according to whether or not the patient is able to understand). The maximum score is 10 points and the minimum score, and greatest neurological impairment is 1.5 points, with scores 1–4 indicating severe deficit, 5–7 moderate deficit, and scores equal to or less than 8 indicating mild deficit.19

The patients' literacy was measured using the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS_EU_Q16)20 at baseline and at the end of the study (Table 2). This scale is made up of 16 items with four possible answers: very difficult and difficult = 0 and very easy = 1, and don't know don't answer. The scores are totalled and a score between 0 and 12 is considered an ‘inadequate or problematic’ level and a score between 13 and 16 ‘sufficient’.20

Measurement of variables in the different sessions.

| Evaluation | Abbreviation | Objective | Measurement of sessions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable scale | Main objective | B0a | PIb | |

| European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire | HLS_EU_Q16 | To measure health literacy level | x | x |

| Secondary variables | B0a | PIb | ||

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | HADS | Anxiety | x | 0 |

| Depression | x | 0 | ||

| Canadian Neurological Scale | Canadian scale | Neurological status | x | 0 |

The variables in this study were entered into a database for analysis by an external investigator to ensure anonymisation of the data.

A descriptive analysis of demographic and clinical characteristics was performed for the IG and CG. Results were presented as mean and standard deviation, median, and interquartile range for the HLS-EU-Q-16 scale variables obtained with skewed distribution.

The non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used to analyse the literacy levels in both the IG and CG before and after the intervention.

Fisher's χ2 test was used to analyse the relationship between health literacy in the IG and CG before and after the intervention.

The analysis was conducted in two parts for literacy level. First, the pre-intervention literacy level was measured across the two groups; second, the change between pre-intervention and post-intervention literacy level was analysed.

The results were considered statistically significant at a p-value <.05. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28 IBM, 290 M (Armonk, New York, USA) was used for this purpose. Finally, the statisticians who performed the analyses were blinded to the allocation of participants.

Ethical and legal aspectsThe Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos de la Comunidad de Madrid approved the study. The basic principles in research were respected in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and all subjects who participated in the study were informed verbally and in writing and signed their IC.

Project registration in ClinicalTrials.gov: NTC05143385.

ResultsAll participants who started the clinical trial completed the study. A total of four patients were randomly allocated to the IG and eight patients to the CG.

The sample (n = 12) consisted of 50% men with a mean age of 51.16 (±5.33) years, of whom 58.33% had suffered a haemorrhagic stroke and 41.66% an ischaemic stroke.

The main caregivers were 58.33% spouses, 25% parents, 16.6% siblings.

The neurological assessment measured using the Canadian Neurological Scale showed that 66.66% of the patients participating in the study had a mild impairment score, and 33.33% had moderate impairment scores. A total of 58.33% of the patients had dyslipidaemia and 75% were hypertensive.

Seventy-five percent of the patients had no anxiety and 25% had a full clinical picture of anxiety. With regard to depression, the following values were obtained: 50% showed no signs or symptoms of depression, 33.33% had a complete clinical picture, and 16.66% had symptoms associated with the disorder (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences between the socio-demographic variables (Table 3).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included in the study.

| CEADAC (n = 12) | IG (n = 4) | CG (n = 8) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 49.75 (±4.023) | 51.87 (5.75) | .0669c | ||

| Sexb(%) | Males (n = 4) | Females (n = 0) | Males (n = 2) | Females (n = 6) | .061d |

| 100 | 0 | 25 | 75 | ||

| Type of strokeb(%) | .576d | ||||

| Ischaemic | 25 | 50 | |||

| Haemorrhagic | 75 | 50 | |||

| Main caregiverb(%) | .276d | ||||

| Spouse | 50 | 62,5 | |||

| Parents | 50 | 12,5 | |||

| Siblings | 0 | 25 | |||

| Canadian scaleb | .547d | ||||

| Mild | 50 | 75 | |||

| Moderate | 50 | 25 | |||

| Severe | 0 | 0 | |||

| Time since strokea | 77,05 (± 24,23) | 70,75 (± 18,35) | .798c | ||

| Hypertensiveb (%) | 78 | 75 | .491d | ||

| Dyslipidaemiab (%) | 42 | 38 | .576d | ||

| HADS-Ab(%) | .491d | ||||

| No symptoms | 100 | 62,5 | |||

| Full clinical picture | 0 | 0 | |||

| Presence of considerable symptoms and a likely case | 0 | 37,5 | |||

| HADS-Db(%) | .472d | ||||

| No symptoms | 50 | 50 | |||

| Full clinical picture | 0 | 25 | |||

| Presence of considerable symptoms and a likely case | 50 | 25 | |||

If we refer to the data obtained with regard to the level of literacy at study baseline, 41% of the patients had an inadequate or problematic level and 58% had a sufficient level. Of the IG patients, 25% had an inadequate or problematic level of health literacy before the intervention and 75% of the patients had a sufficient level of health literacy. After the intervention, 100% of the patients achieved a sufficient level of health literacy. In the CG, at baseline 50% of the patients had insufficient or problematic health literacy levels and 50% sufficient levels. After six weeks of conventional rehabilitation, the same results were obtained for health literacy levels in the CG.

To the questions on understanding how to take medication and whether they knew when a second medical opinion was needed, 58% responded that they found it very difficult to understand the doctor's or pharmacist's instructions. However, with regard to questions concerning their self-care, 58% of patients responded that they found it easy to understand what was beneficial for them in their self-care.

Categorisation of Health Literacy LevelPre-study values for literacy levels measured with the HLS_EU_Q16 scale reported different values in the CG and IG, the CG having the lowest literacy level compared to the literacy level in the IG (9 vs. 13.75; p = .57). There were no statistically significant differences (p = .57) between the control and intervention groups (Table 4). The IG participants obtained higher literacy values after the intervention than the CG participants (14.75 vs. 9.38; p = .208) and the IG obtained minimally better literacy scores (9 vs. 9.38; p = .180) (Table 4). The IG also had higher literacy scores after the VR intervention (13.75 vs. 14.25; p = .317).

Comparison of health literacy level before and after the intervention.

| IG | IG | p-value* | CG | CG | p-value* | p-value baseline | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI vs. GC | post-intervention | |||||||

| IG vs. CG | ||||||||

| Baseline | 6 weeks | Baseline | 6 weeks | |||||

| HLS-EU-Q-16 | 14.50 [4.75]a | 14.50 [3.25]a | .317b | 9.50 [13.75]a | 9.50 [12.5]a | .180b | .576c | .208c |

HLS-EU-Q-16: Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire.

Both the IG and the CG had improved outcomes in health literacy following the 6-week non-immersive VR intervention. No statistically significant differences were obtained in either the IG or the CG for us to affirm the effectiveness of VR in improving literacy in patients admitted with stroke to neurorehabilitation units.

These results could be explained by the age, depression, and neurological damage of the participants.21

In a study by Flink et al. on health literacy, the study participants were older than those of our study; moreover, the reported data revealed better levels of health literacy prior to the study than the data obtained in our study. In this study the depression levels of the patients were also lower than in our study patients. Regarding the impact of stroke on patients, the data obtained were similar in both studies.21 The literature reviewed on degree of health literacy revealed that patients who were older than the participants in our study showed a higher degree of literacy.22,23 In the study by Brega et al. on health literacy and cardiovascular risk, the age of the patients was similar to that of our study and the literacy of the patients was lower.24

Studies on stroke patients and medication literacy showed that younger patients had a higher degree of medication literacy compared that of older patients.25 In our study, the patients found the questions on understanding the doctor's or pharmacist's instructions on how to take the prescribed medication and following the doctor's or pharmacist's instructions the most difficult to answer.25

As there is a relationship between literacy, depression, functioning, and cognitive status after stroke, health literacy may be an important factor to consider in recovery.21 In their systematic review, Paasche-Orlow et al. stated that patients' health literacy will be influenced by age, education, and ethnicity.26 Other studies reviewed state that the ability to understand health information and the ability to actively interact with professionals is associated with important health behaviours and health status, health literacy being a major determinant in cardiovascular disease prevention.27

To our knowledge, this pilot study is the first to study the association between stroke patients and VR as a tool to improve health literacy. In addition, there are few studies in which any intervention has been conducted to improve health literacy in stroke patients or that have measured health literacy levels in stroke patients.

The study being undertaken in a single centre meant limited access to a larger sample, and therefore our results should be interpreted with caution. It is recommended that this study be replicated with a larger sample, in more than one neurorehabilitation centre and with a longer intervention time.

ConclusionsIn our study we found no significant differences in the use of VR as an effective tool in improving the health literacy of stroke patients.

We consider it important to extend our study to more centres and with a larger sample size to draw conclusions.

FundingThe project was supported by the Spanish Society of Neurological Nursing (SEDENE), which contributed financially to the study through the Third Prize for the best International Research Project in Neurological Nursing 2021, at the 28th Spanish Neurological Nursing Congress.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

This project was supported by the Spanish Society of Neurological Nursing (SEDENE).