Foreign Accent Syndrome (FAS) is an acquired speech disorder due to a lesion of the central nervous system, characterized by the appearance of a foreign accent when speaking the native language.

The objective is to describe a case of SAE as a form of presentation of a stroke.

DevelopmentMale, 72 years old, Spanish, with ischemic heart disease, dyslipidemia, COPD. Autonomous for Activities of Daily Living. Admitted for chest pain on slight exertion. Presents difficulty in responding and obeying orders, feels that the accent and speed of speech are different. His relatives say that he speaks like the English, but in Spanish.

In neurological examination conscious, oriented, obeys orders, no dysarthria. Language is clear, fluent and intelligible, with alteration of intonation and rhythm. Mild right facial paresis.

ResultsA care plan was developed based on Gordon’s functional patterns, with NANDA diagnoses, interventions (NIC) and expected outcomes (NOC). Due to the rarity of the case it is justified to establish an individualized care plan, obtaining 7 nursing diagnoses and 12 nursing interventions with their respective NOC.

The Clinical Judgment was of ischemic stroke of cardioembolic origin. The evolution was favorable, after 3 months she recovered her normal accent and did not report any speech alteration or identity problems.

ConclusionSAE is an infrequent syndrome, which can generate identity conflicts if it does not subside.

We consider it necessary to be aware of this syndrome so that it can be recognized early, and to be able to offer a correct nursing approach that guarantees quality care and psychological support.

El Síndrome del Acento Extranjero (SAE), es una alteración adquirida del habla por una lesión del sistema nervioso central, caracterizada por la aparición de un acento extranjero al hablar la lengua materna.

El objetivo es describir un caso de SAE como forma de presentación de un Ictus.

DesarrolloVarón, 72 años, español, con Cardiopatía Isquémica, dislipemia, EPOC. Autónomo para las Actividades de la Vida diaria. Ingresa por dolor torácico de pequeños esfuerzos. Presenta dificultad para responder y obedecer órdenes, siente que el acento y velocidad del habla son diferentes. Sus familiares dicen que habla como los ingleses, pero en español.

En la exploración neurológica se mostró consciente, orientado, obedecía órdenes, no disartria. Lenguaje claro, fluido e inteligible, con alteración de entonación y ritmo. Paresia facial derecha leve.

ResultadosSe desarrolló un plan de cuidados basado en patrones funcionales de Gordon, con diagnósticos NANDA, intervenciones (NIC) y resultados esperados (NOC). Debido a la rareza del caso está justificado establecer un plan de cuidados individualizado, obteniéndose 7 Diagnósticos de enfermería y 12 Intervenciones de enfermería con sus respectivos NOC.

El Juicio Clínico fue de Ictus Isquémico tipo minor de origen cardioembólico. La evolución fue favorable, a los 3 meses recupero el acento normal y no refería alteración del habla ni problema de identidad.

ConclusiónEl SAE es un síndrome infrecuente, que puede generar conflictos de identidad si no remite.

Consideramos necesario conocer este síndrome para que pueda ser reconocido precozmente, y poder ofrecer un correcto abordaje por enfermería que garanticen unos cuidados de calidad y apoyo psicológico.

Foreign accent syndrome (FAS) or “pseudo-foreigner” was first described just over a century ago by the French neurologist Marie (1907).1 It is a rare speech disorder characterised by the appearance of an accent which differs from one’s native language. The impression of accent shift is considered to be the result of a combination of segmental and suprasegmental impairments. Due to the diverse aetiologies and locations of heterogeneous lesions, it remains controversial whether there is sufficient consistency or universality to treat FAS as a “syndrome”.2

Since only a few cases have been published in the scientific literature and, above all, because of the diverse particularities presented in each of the patients, the exact location of this disorder in the brain has yet to be determined. However, a majority of individuals have lesions in the basal ganglia or areas close to them, as well as in the left hemisphere, commonly associated with the language domain area, and in the frontal lobe of the brain. Selective damage to the basal ganglia or surrounding regions is observed, or with a lesion to the premotor or motor regions in the left hemisphere of the cortex.3

In most cases it presents as an acquired condition due to lesions secondary to a stroke, trauma, multiple sclerosis, in the dominant hemisphere for speech, involving left fronto-temporo-parietal and subcortical regions. The symptoms may persist for months or years, or disappear spontaneously or progressively; and in a smaller number of cases it presents briefly in patients with psychiatric disorders, schizophrenia and conversion disorder.4

The listener’s role is extremely important in these types of cases, since it is the listener who perceives the patient’s speech as foreign and it must be also taken into account that in many cases, those affected by this syndrome are not aware of this change in accent until they are told about it. For his part or his part, Monrad-Krohn suggested that the main cause that leads to perceiving the foreignness in a patient's speech was dysprosody.5 This is an abnormal prosody, in the sense that it does not correspond to the accent of the native language, since there is an altered use of its prosody. The individual speech of each of the patients with FAS maintains the stereotypical properties and attributes of the languages, which is why they are often considered to produce a generic accent. This concept of generic is based on the impressions of the foreign accent by the listeners, since they point out that the properties of the patients’ speech have universal properties that are found in the natural language. This is probably because FAS does not involve sound variants that are specific to a native language variety.6 Furthermore, an interesting feature of FAS is that the patient does not have to have been previously exposed to an environment specific to the foreign accent that he or she now produces. It is not even necessary for the person to have spoken that language variety before, to have any contact with a native speaker of that language, or to manifest certain psychological or psychiatric conditions that lead them to alter their way of speaking.7

ObjectiveTo describe a clinical case of foreign accent syndrome after a stroke.

Case descriptionMale, 72 years old, Spanish, with cardiovascular risk factors (ischaemic heart disease, acute myocardial infarction, dyslipidemia) and associated comorbidity (chronic lung disease, obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, benign prostatic hypertrophy). Autonomous for basic activities of daily living, score on the modified Rankin Scale of 1.

He was admitted to Cardiology for chest pain on minor exertion and coronary artery disease known since 1991. He did not usually follow the diet recommended by his primary care team, which prescribed a cardiac diet.

During admission, the patient was assessed by M. Gordon’s functional health patterns.

On the Saturday morning he had difficulty answering questions and obeying orders when he was assessed by Neurology. From then onwards, the patient stated that he felt the accent of his speech and the speed of his speech was different. His relatives told him that he spoke as if he were English but in Spanish.

During the neurological examination, he appeared conscious, oriented, obeyed orders and answered questions, did not appear to have any speech alterations, but did have a foreign accent, with no dysarthria. Clear, fluent language, although with alterations in intonation and speech rhythm. Mild right facial paresis. Preserved sensitivity, no motor deficit in the extremities. No dysmetria. Normal gait with adequate base. The CT scan performed was normal.

As a consequence of this stroke, the patient began to speak (Spanish) as if he were a foreigner. His speech was perfectly intelligible, but it sounded like a “foreign accent” that the patient was unable to avoid. The patient and his family felt strange when listening to him.

He was diagnosed with minor ischaemic stroke of the left middle cerebral artery region of cardioembolic origin, in addition to coronary artery disease of the main trunk and three vessels with an indication for surgical revascularisation.

Upon discharge from hospital, the patient maintained his foreign accent, having recovered from facial paresis. He did not require rehabilitation. An echocardiogram was requested to rule out the presence of intracavitary thrombi and to assess the start of oral anticoagulation.

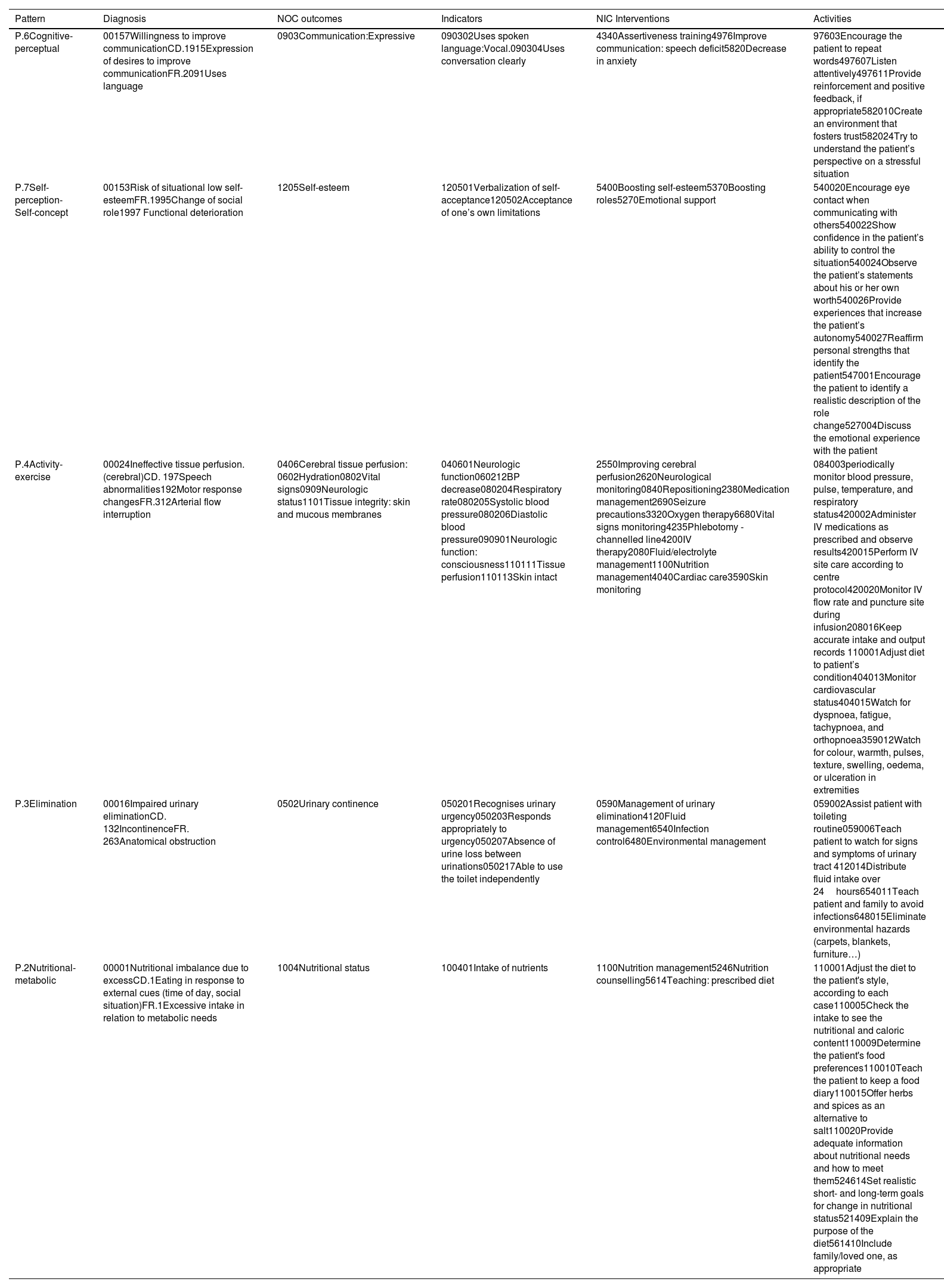

An individualised care plan was developed and implemented based on Gordon’s functional health patterns, with NANDA diagnoses, interventions (NIC) and expected outcomes according to the classification of outcomes (NOC). Due to the rarity of the case/problem, the establishment of an individualised care plan was justified, obtaining 7 nursing diagnoses and 12 nursing interventions with their respective NOC. Through this care plan, the identified diagnoses and potential complications were resolved (Table 1).

Individualised care plan.

| Pattern | Diagnosis | NOC outcomes | Indicators | NIC Interventions | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P.6Cognitive-perceptual | 00157Willingness to improve communicationCD.1915Expression of desires to improve communicationFR.2091Uses language | 0903Communication:Expressive | 090302Uses spoken language:Vocal.090304Uses conversation clearly | 4340Assertiveness training4976Improve communication: speech deficit5820Decrease in anxiety | 97603Encourage the patient to repeat words497607Listen attentively497611Provide reinforcement and positive feedback, if appropriate582010Create an environment that fosters trust582024Try to understand the patient’s perspective on a stressful situation |

| P.7Self-perception-Self-concept | 00153Risk of situational low self-esteemFR.1995Change of social role1997 Functional deterioration | 1205Self-esteem | 120501Verbalization of self-acceptance120502Acceptance of one’s own limitations | 5400Boosting self-esteem5370Boosting roles5270Emotional support | 540020Encourage eye contact when communicating with others540022Show confidence in the patient’s ability to control the situation540024Observe the patient’s statements about his or her own worth540026Provide experiences that increase the patient’s autonomy540027Reaffirm personal strengths that identify the patient547001Encourage the patient to identify a realistic description of the role change527004Discuss the emotional experience with the patient |

| P.4Activity-exercise | 00024Ineffective tissue perfusion.(cerebral)CD. 197Speech abnormalities192Motor response changesFR.312Arterial flow interruption | 0406Cerebral tissue perfusion: 0602Hydration0802Vital signs0909Neurologic status1101Tissue integrity: skin and mucous membranes | 040601Neurologic function060212BP decrease080204Respiratory rate080205Systolic blood pressure080206Diastolic blood pressure090901Neurologic function: consciousness110111Tissue perfusion110113Skin intact | 2550Improving cerebral perfusion2620Neurological monitoring0840Repositioning2380Medication management2690Seizure precautions3320Oxygen therapy6680Vital signs monitoring4235Phlebotomy - channelled line4200IV therapy2080Fluid/electrolyte management1100Nutrition management4040Cardiac care3590Skin monitoring | 084003periodically monitor blood pressure, pulse, temperature, and respiratory status420002Administer IV medications as prescribed and observe results420015Perform IV site care according to centre protocol420020Monitor IV flow rate and puncture site during infusion208016Keep accurate intake and output records 110001Adjust diet to patient’s condition404013Monitor cardiovascular status404015Watch for dyspnoea, fatigue, tachypnoea, and orthopnoea359012Watch for colour, warmth, pulses, texture, swelling, oedema, or ulceration in extremities |

| P.3Elimination | 00016Impaired urinary eliminationCD. 132IncontinenceFR. 263Anatomical obstruction | 0502Urinary continence | 050201Recognises urinary urgency050203Responds appropriately to urgency050207Absence of urine loss between urinations050217Able to use the toilet independently | 0590Management of urinary elimination4120Fluid management6540Infection control6480Environmental management | 059002Assist patient with toileting routine059006Teach patient to watch for signs and symptoms of urinary tract 412014Distribute fluid intake over 24hours654011Teach patient and family to avoid infections648015Eliminate environmental hazards (carpets, blankets, furniture…) |

| P.2Nutritional-metabolic | 00001Nutritional imbalance due to excessCD.1Eating in response to external cues (time of day, social situation)FR.1Excessive intake in relation to metabolic needs | 1004Nutritional status | 100401Intake of nutrients | 1100Nutrition management5246Nutrition counselling5614Teaching: prescribed diet | 110001Adjust the diet to the patient's style, according to each case110005Check the intake to see the nutritional and caloric content110009Determine the patient's food preferences110010Teach the patient to keep a food diary110015Offer herbs and spices as an alternative to salt110020Provide adequate information about nutritional needs and how to meet them524614Set realistic short- and long-term goals for change in nutritional status521409Explain the purpose of the diet561410Include family/loved one, as appropriate |

Evolution was favourable; the patient had recovered his normal accent at the 3-month review and did not report any alteration of speech in terms of fluency or rhythm, and no identity problems.

DiscussionThe diagnosis of minor ischaemic stroke of cardioembolic origin was established based on the findings of the clinical examination with the manifestation of FAS and mild facial paresis.

Haley et al. conducted a review of 30 cases in the literature and found that most presented lesions in the left frontal region, anterior and dorsal to the head of the caudate nucleus, the aetiology was vascular or traumatic and it occurred in the recovery period.8

In the first case reported in Mexico, the patient presented FAS in the recovery period after left fronto-temporo-parietal tumour resection. Clinically he presented segmental and prosodic deficits, with no data of dysarthria or aphasia being found. The FAS persisted up to 4 months after the surgical event without affecting communication or daily life. In the evaluation, an accent similar to American English was perceived. In the literature it has been described that the perceived accent can vary with each subject who hears it, with this being associated with the origin of the languages that he has previously perceived. The clinical manifestations, duration and location of the lesion correlate with those reported in the literature.9

This little-known disorder is perhaps underdiagnosed and poorly classified. It is necessary to continue to closely monitor the case and perform a thorough analysis of the pre- and post-surgical imaging studies to describe a possible pathological model. The individualised care plan enables the needs of the person suffering from FAS to be analysed and determined, setting objectives and a set of activities to achieve them in a given period of time, to improve the quality of life of each patient.

Some authors have considered a neurogenic origin of FAS, pending future conclusive studies. Keulen et al. consider a variant of FAS to be psychogenic. In contrast, Miller, Lowit and O’Sullivan support the idea that the changes produced in the speech of FAS may have the same physiological basis as other motor disorders with alterations in speech production such as dysarthria or apraxia.10

ConclusionFAS is a rare neuromotor language disorder syndrome, with low incidence but which can generate identity conflicts if the disorder does not subside.

We believe it necessary to familiarise ourselves with this syndrome so that it can be recognised and differentiated early from other processes, and thus be able to offer a correct approach through nursing that guarantees safe and quality care in addition to psychological support to the patient, if necessary.

Treatment is intended to restore normal speech, so techniques for improving prosodic, rhythm and natural speech will be taken into account, as well as systematic exercises of vocal articulation.

The emotional aspects of this syndrome are of note. The patient faces not so much situations typical of a patient in his environment, but those typical of a foreign speaker. This has important emotional implications related to the sudden loss of personal identity and the feeling of not belonging to his speaking community.

FundingThis study did not receive any funding.

Conflict of interestsThe research team has no conflict of interests.

We wish to thank the patient and his family for their collaboration: to Irene, Jaime and Elena.