Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a highly prevalent pathology that has not been clearly defined. Currently, there is no universally accepted treatment protocol, and the diagnostic markers, etiology, and specific pathophysiology for developing effective non-pharmacological treatments remain unknown.

ObjectiveTo determine the currently established rehabilitation treatment methodologies for CFS. In addition, to establish an analysis of the efficacy of the treatment plans studied and to determine advances on the etiology of CFS.

MethodsA systematic review of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) published since 2011 was conducted. Studies evaluating non-pharmacological interventions for adult CFS patients were included, differentiating them according to chosen diagnostic criteria and variable measurement. The treatment hypothesis of the selected interventions was also taken into account.

Results17 RCTs were included, 6 of which based their performance protocol on a self-management booklet and 11 of which did so through face-to-face involvement of a therapist and active therapy. The results of these studies were assessed primarily by patient-reported outcomes, and 5 of these studies reported on objective outcome measures.

ConclusionThere is no significant evidence on the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions in CFS patients. In addition, the lack of consensus on diagnostic criteria makes it difficult to compare studies and to develop a standardised treatment plan. Advances in the aetiology and pathophysiology of CFS point to the need for a broader therapeutic approach.

El síndrome de fatiga crónica (SFC) es una patología de alta prevalencia que no ha sido definida con claridad. En la actualidad, no existe un protocolo de tratamiento universalmente aceptado, y los marcadores diagnósticos, la etiología y la fisiopatología específica para desarrollar tratamientos no farmacológicos eficaces siguen siendo desconocidos.

ObjetivoDeterminar las metodologías de tratamiento de rehabilitación establecidas actualmente para el SFC. Además, establecer un análisis de la eficacia de los planes de tratamiento estudiados y determinar los avances sobre la etiología del SFC.

MétodoSe llevó a cabo una revisión sistemática de ensayos clínicos aleatorizados (ECA) publicados desde el 2011. Se incluyeron estudios que evaluaban las intervenciones no farmacológicas para pacientes adultos con SFC, diferenciándolos según criterios diagnósticos escogidos y medición de variables. Asimismo, se tuvo en cuenta la hipótesis de tratamiento de las intervenciones seleccionadas.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 17 ECA, 6 de los cuales basaron su protocolo de actuación en un folleto de autogestión y 11 lo hicieron a través de la participación presencial de un terapeuta y terapia activa. Los resultados de estos estudios se evaluaron principalmente mediante medidas de resultado informadas por el paciente y 5 de estos estudios informaron sobre medidas de resultado objetivas.

ConclusiónNo existen evidencias de carácter significativo sobre la eficacia de las intervenciones no farmacológicas en pacientes con SFC. Además, la falta de consenso en los criterios diagnósticos dificulta la comparación entre estudios y la elaboración de un plan de tratamiento estandarizado. Los avances en la etiología y fisiopatología del SFC apuntan a la necesidad de un abordaje terapéutico más amplio.

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) or myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) is one of the most prevalent neurological diseases today,1 affecting .07–2.6% of the world's population.

In recent years, the incidence of CFS has increased due to its relationship with severe acute respiratory syndrome type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and its chronic form, long-term COVID.2

This pathology is associated with a low quality of life due to a decrease in the patient's activity levels, affecting job performance and social interactions.3 Its incidence is higher in women than in men and it affects all age ranges and demographic groups.4

For years CFS was included in the group of psychiatric diseases, being approached through the psychogenic or psychosomatic model and considering its perpetuation due to avoidance behaviours, health anxiety, hypochondria or personality traits. However, this theory was discarded after learning about the involvement of post-exertional malaise (PEM), which is characterised by a marked and rapid physical and/or cognitive fatigability with minimal effort, an exacerbation of symptoms after effort, immediate or delayed exhaustion after exercise, a prolonged recovery period (24 h or more) and a low threshold of physical and mental fatigability. Currently, CFS is considered a chronic disease with a low rate of recovery of functionality.5

Regarding symptoms, CFS includes PEM, cognitive impairment, sleep disorders, autonomic dysfunction and/or muscle or joint pain, headache, concentration or short-term memory problems, flu-like syndrome, susceptibility to infections, digestive disorders, nocturia, etc.1,6

With regards to diagnostic criteria guides, the most commonly used in CFS are the Oxford criteria from 1991,7 the criteria of the Centre for Disease Control (Fukuda, 1994),8 the Canadian consensus criteria (CCC) of 2003,9 the international consensus criteria for ME (ME-ICC10 and the criteria for systemic exertion intolerance disease (SEID).

However, the clinical approach guidelines do not specify which population they are aimed at, with the standard treatment for mild or moderate CFS being cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET), both accepted by the Centres for Disease Control in the USA and the NICE guidelines in the United Kingdom.11

Regarding its aetiology, since 2012 CFS has been studied as a central sensitisation disorder due to hyper reactivity of the CNS to extrinsic and intrinsic stimuli,12 but currently there is no clear definition or a universally accepted treatment or prevention plan.

Against this backdrop, our main objective with this systematic review was to provide updated awareness of the rehabilitation treatment methodologies currently established for CFS. Furthermore, we sought to establish an analysis of the efficacy of studied treatment plans and to determine advances on the aetiology and pathophysiology of the disease.

MethodDesignA systematic review was conducted to evaluate the treatment methodology of non-pharmacological interventions applied in patients with CFS, according to their efficacy and methodology of action. The studies were grouped and evaluated according to the therapy used, the diagnostic criteria and the measurement of variables. The review was limited to randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

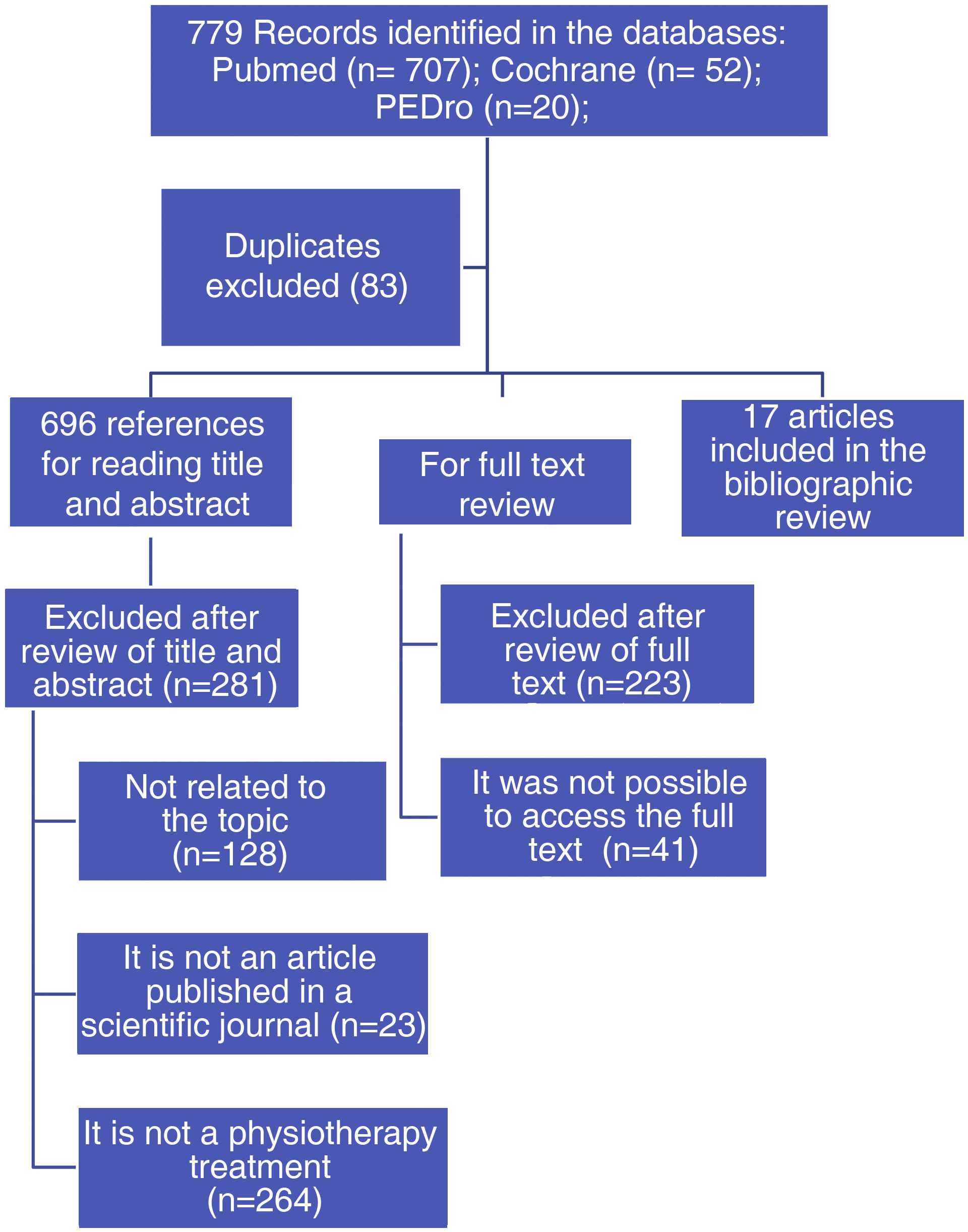

Search criteriaThe recommendations of the PRISMA13 guideline were followed in carrying out this systematic review. A literature search was conducted using the main electronic literature databases Pubmed (www.pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), Cochrane (www.cochrane.org) and PEDro (www.pedro.org.au/spanish/), covering the period from 2011 to June 2022. This timeline was chosen due to the great boom in the pathology in the last 10 years, the diagnostic advances that have occurred, and the latest change in the definition of CFS in the international consensus criteria in 2011.

The search terms used were: (Fatigue Syndrome, Chronic OR Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) AND (Physical Therapy OR Treatment) AND (Randomized Controlled Trial OR Clinical Trial OR Systematic Review). The type of trial was limited to RCTs and all languages were included.

Selection criteriaArticles meeting the following criteria were selected:

- a)

An empirical study published in full text in a scientific journal.

- b)

Research on possible physiotherapeutic treatments, carried out individually or in a multidisciplinary team, aimed at improving the symptoms of CFS.

- c)

Adult patients over 18 years of age.

- d)

Primary diagnosis of CFS according to international criteria or the Centre for Disease Control, Fukuda, Oxford, NICE guidelines, Canadian diagnostic criteria, London or the hospital's own criteria (provided that they specify the eligibility criteria).

- e)

Patients who do not have another serious comorbidity condition, medical (e.g., cancer, multiple sclerosis, etc.) and/or psychological (e.g., depression with suicidal ideation, schizophrenia, etc.)

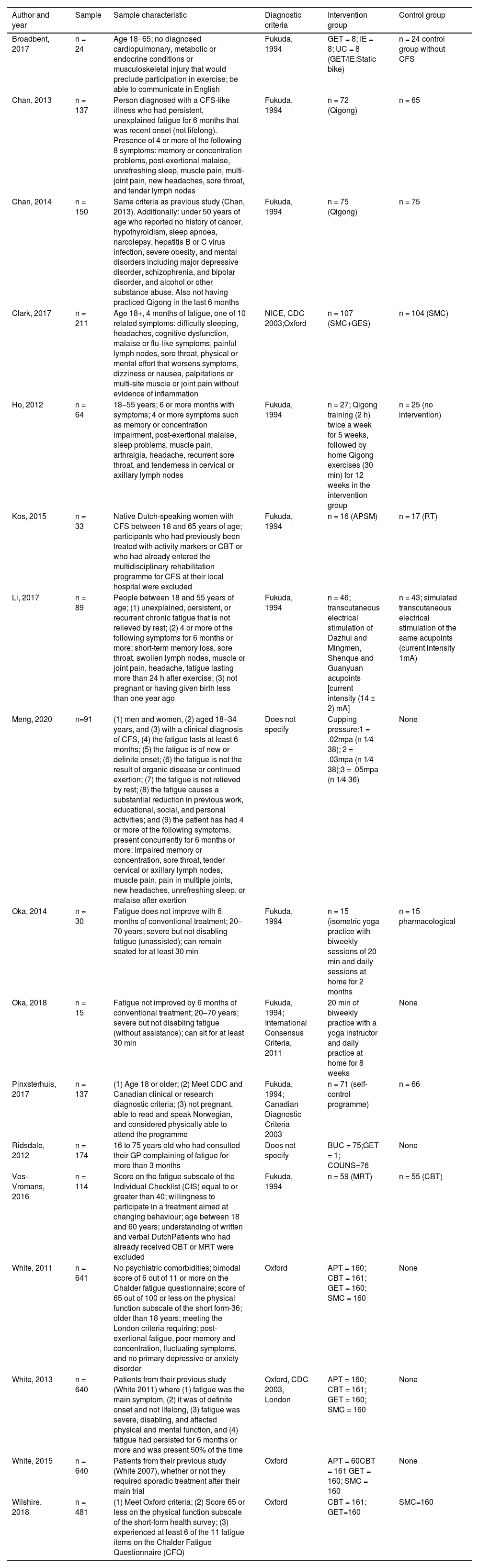

Data included were: objectives, number of participants, age, definition criteria used for diagnosis (Table 1), treatment period, measurement tools, distribution of control and performance groups, measurement variables were taken into account. Data were also obtained regarding the effectiveness of the treatment compared to the control group and the conclusion expressed by the authors (Table 2).

Sample characteristics.

| Author and year | Sample | Sample characteristic | Diagnostic criteria | Intervention group | Control group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broadbent, 2017 | n = 24 | Age 18−65; no diagnosed cardiopulmonary, metabolic or endocrine conditions or musculoskeletal injury that would preclude participation in exercise; be able to communicate in English | Fukuda, 1994 | GET = 8; IE = 8; UC = 8 (GET/IE:Static bike) | n = 24 control group without CFS |

| Chan, 2013 | n = 137 | Person diagnosed with a CFS-like illness who had persistent, unexplained fatigue for 6 months that was recent onset (not lifelong). Presence of 4 or more of the following 8 symptoms: memory or concentration problems, post-exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, muscle pain, multi-joint pain, new headaches, sore throat, and tender lymph nodes | Fukuda, 1994 | n = 72 (Qigong) | n = 65 |

| Chan, 2014 | n = 150 | Same criteria as previous study (Chan, 2013). Additionally: under 50 years of age who reported no history of cancer, hypothyroidism, sleep apnoea, narcolepsy, hepatitis B or C virus infection, severe obesity, and mental disorders including major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, and alcohol or other substance abuse. Also not having practiced Qigong in the last 6 months | Fukuda, 1994 | n = 75 (Qigong) | n = 75 |

| Clark, 2017 | n = 211 | Age 18+, 4 months of fatigue, one of 10 related symptoms: difficulty sleeping, headaches, cognitive dysfunction, malaise or flu-like symptoms, painful lymph nodes, sore throat, physical or mental effort that worsens symptoms, dizziness or nausea, palpitations or multi-site muscle or joint pain without evidence of inflammation | NICE, CDC 2003;Oxford | n = 107 (SMC+GES) | n = 104 (SMC) |

| Ho, 2012 | n = 64 | 18−55 years; 6 or more months with symptoms; 4 or more symptoms such as memory or concentration impairment, post-exertional malaise, sleep problems, muscle pain, arthralgia, headache, recurrent sore throat, and tenderness in cervical or axillary lymph nodes | Fukuda, 1994 | n = 27; Qigong training (2 h) twice a week for 5 weeks, followed by home Qigong exercises (30 min) for 12 weeks in the intervention group | n = 25 (no intervention) |

| Kos, 2015 | n = 33 | Native Dutch-speaking women with CFS between 18 and 65 years of age; participants who had previously been treated with activity markers or CBT or who had already entered the multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme for CFS at their local hospital were excluded | Fukuda, 1994 | n = 16 (APSM) | n = 17 (RT) |

| Li, 2017 | n = 89 | People between 18 and 55 years of age; (1) unexplained, persistent, or recurrent chronic fatigue that is not relieved by rest; (2) 4 or more of the following symptoms for 6 months or more: short-term memory loss, sore throat, swollen lymph nodes, muscle or joint pain, headache, fatigue lasting more than 24 h after exercise; (3) not pregnant or having given birth less than one year ago | Fukuda, 1994 | n = 46; transcutaneous electrical stimulation of Dazhui and Mingmen, Shenque and Guanyuan acupoints [current intensity (14 ± 2) mA] | n = 43; simulated transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the same acupoints (current intensity 1mA) |

| Meng, 2020 | n=91 | (1) men and women, (2) aged 18–34 years, and (3) with a clinical diagnosis of CFS, (4) the fatigue lasts at least 6 months; (5) the fatigue is of new or definite onset; (6) the fatigue is not the result of organic disease or continued exertion; (7) the fatigue is not relieved by rest; (8) the fatigue causes a substantial reduction in previous work, educational, social, and personal activities; and (9) the patient has had 4 or more of the following symptoms, present concurrently for 6 months or more: Impaired memory or concentration, sore throat, tender cervical or axillary lymph nodes, muscle pain, pain in multiple joints, new headaches, unrefreshing sleep, or malaise after exertion | Does not specify | Cupping pressure:1 = .02mpa (n 1⁄4 38); 2 = .03mpa (n 1⁄4 38);3 = .05mpa (n 1⁄4 36) | None |

| Oka, 2014 | n = 30 | Fatigue does not improve with 6 months of conventional treatment; 20–70 years; severe but not disabling fatigue (unassisted); can remain seated for at least 30 min | Fukuda, 1994 | n = 15 (isometric yoga practice with biweekly sessions of 20 min and daily sessions at home for 2 months | n = 15 pharmacological |

| Oka, 2018 | n = 15 | Fatigue not improved by 6 months of conventional treatment; 20–70 years; severe but not disabling fatigue (without assistance); can sit for at least 30 min | Fukuda, 1994; International Consensus Criteria, 2011 | 20 min of biweekly practice with a yoga instructor and daily practice at home for 8 weeks | None |

| Pinxsterhuis, 2017 | n = 137 | (1) Age 18 or older; (2) Meet CDC and Canadian clinical or research diagnostic criteria; (3) not pregnant, able to read and speak Norwegian, and considered physically able to attend the programme | Fukuda, 1994; Canadian Diagnostic Criteria 2003 | n = 71 (self-control programme) | n = 66 |

| Ridsdale, 2012 | n = 174 | 16 to 75 years old who had consulted their GP complaining of fatigue for more than 3 months | Does not specify | BUC = 75;GET = 1; COUNS=76 | None |

| Vos-Vromans, 2016 | n = 114 | Score on the fatigue subscale of the Individual Checklist (CIS) equal to or greater than 40; willingness to participate in a treatment aimed at changing behaviour; age between 18 and 60 years; understanding of written and verbal DutchPatients who had already received CBT or MRT were excluded | Fukuda, 1994 | n = 59 (MRT) | n = 55 (CBT) |

| White, 2011 | n = 641 | No psychiatric comorbidities; bimodal score of 6 out of 11 or more on the Chalder fatigue questionnaire; score of 65 out of 100 or less on the physical function subscale of the short form-36; older than 18 years; meeting the London criteria requiring: post-exertional fatigue, poor memory and concentration, fluctuating symptoms, and no primary depressive or anxiety disorder | Oxford | APT = 160; CBT = 161; GET = 160; SMC = 160 | None |

| White, 2013 | n = 640 | Patients from their previous study (White 2011) where (1) fatigue was the main symptom, (2) it was of definite onset and not lifelong, (3) fatigue was severe, disabling, and affected physical and mental function, and (4) fatigue had persisted for 6 months or more and was present 50% of the time | Oxford, CDC 2003, London | APT = 160; CBT = 161; GET = 160; SMC = 160 | None |

| White, 2015 | n = 640 | Patients from their previous study (White 2007), whether or not they required sporadic treatment after their main trial | Oxford | APT = 60CBT = 161 GET = 160; SMC = 160 | None |

| Wilshire, 2018 | n = 481 | (1) Meet Oxford criteria; (2) Score 65 or less on the physical function subscale of the short-form health survey; (3) experienced at least 6 of the 11 fatigue items on the Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ) | Oxford | CBT = 161; GET=160 | SMC=160 |

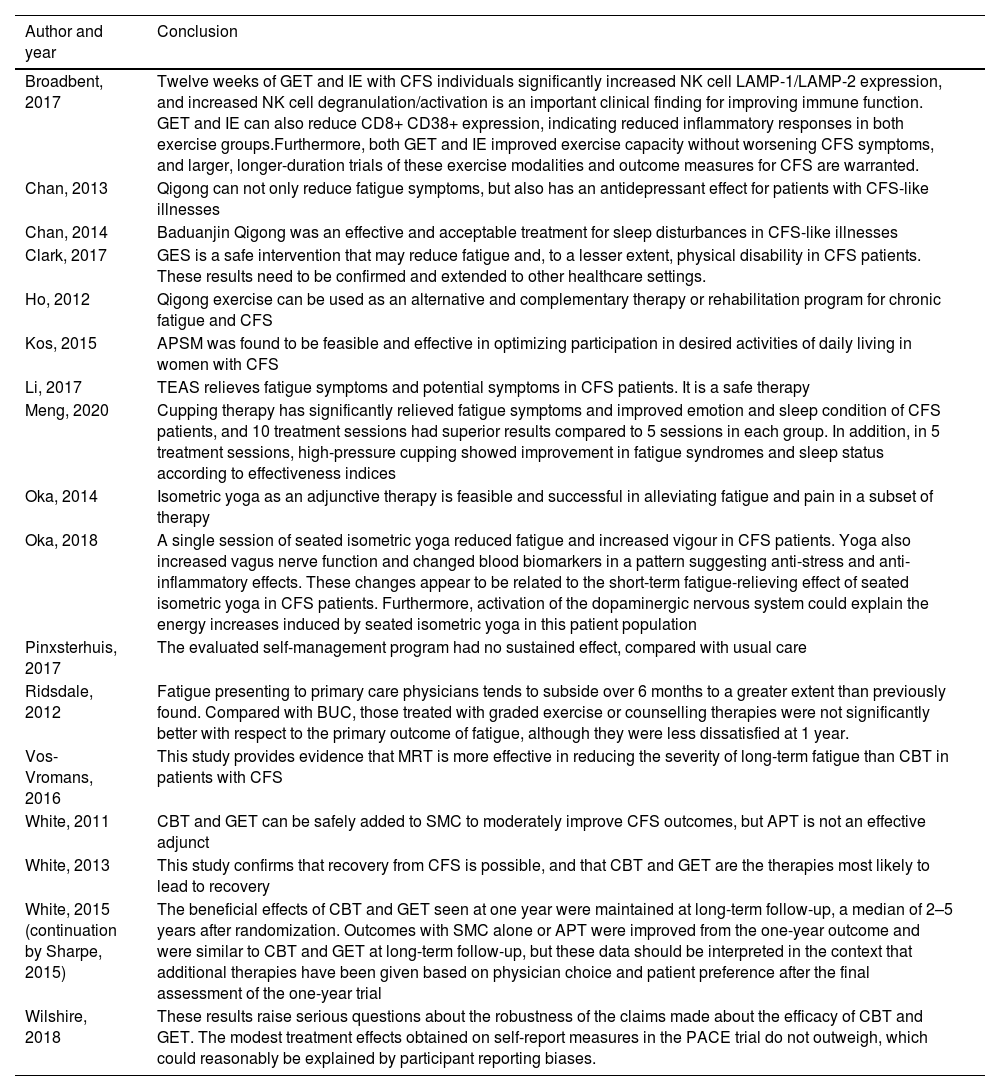

Authors’ conclusions.

| Author and year | Conclusion |

|---|---|

| Broadbent, 2017 | Twelve weeks of GET and IE with CFS individuals significantly increased NK cell LAMP-1/LAMP-2 expression, and increased NK cell degranulation/activation is an important clinical finding for improving immune function. GET and IE can also reduce CD8+ CD38+ expression, indicating reduced inflammatory responses in both exercise groups.Furthermore, both GET and IE improved exercise capacity without worsening CFS symptoms, and larger, longer-duration trials of these exercise modalities and outcome measures for CFS are warranted. |

| Chan, 2013 | Qigong can not only reduce fatigue symptoms, but also has an antidepressant effect for patients with CFS-like illnesses |

| Chan, 2014 | Baduanjin Qigong was an effective and acceptable treatment for sleep disturbances in CFS-like illnesses |

| Clark, 2017 | GES is a safe intervention that may reduce fatigue and, to a lesser extent, physical disability in CFS patients. These results need to be confirmed and extended to other healthcare settings. |

| Ho, 2012 | Qigong exercise can be used as an alternative and complementary therapy or rehabilitation program for chronic fatigue and CFS |

| Kos, 2015 | APSM was found to be feasible and effective in optimizing participation in desired activities of daily living in women with CFS |

| Li, 2017 | TEAS relieves fatigue symptoms and potential symptoms in CFS patients. It is a safe therapy |

| Meng, 2020 | Cupping therapy has significantly relieved fatigue symptoms and improved emotion and sleep condition of CFS patients, and 10 treatment sessions had superior results compared to 5 sessions in each group. In addition, in 5 treatment sessions, high-pressure cupping showed improvement in fatigue syndromes and sleep status according to effectiveness indices |

| Oka, 2014 | Isometric yoga as an adjunctive therapy is feasible and successful in alleviating fatigue and pain in a subset of therapy |

| Oka, 2018 | A single session of seated isometric yoga reduced fatigue and increased vigour in CFS patients. Yoga also increased vagus nerve function and changed blood biomarkers in a pattern suggesting anti-stress and anti-inflammatory effects. These changes appear to be related to the short-term fatigue-relieving effect of seated isometric yoga in CFS patients. Furthermore, activation of the dopaminergic nervous system could explain the energy increases induced by seated isometric yoga in this patient population |

| Pinxsterhuis, 2017 | The evaluated self-management program had no sustained effect, compared with usual care |

| Ridsdale, 2012 | Fatigue presenting to primary care physicians tends to subside over 6 months to a greater extent than previously found. Compared with BUC, those treated with graded exercise or counselling therapies were not significantly better with respect to the primary outcome of fatigue, although they were less dissatisfied at 1 year. |

| Vos-Vromans, 2016 | This study provides evidence that MRT is more effective in reducing the severity of long-term fatigue than CBT in patients with CFS |

| White, 2011 | CBT and GET can be safely added to SMC to moderately improve CFS outcomes, but APT is not an effective adjunct |

| White, 2013 | This study confirms that recovery from CFS is possible, and that CBT and GET are the therapies most likely to lead to recovery |

| White, 2015 (continuation by Sharpe, 2015) | The beneficial effects of CBT and GET seen at one year were maintained at long-term follow-up, a median of 2–5 years after randomization. Outcomes with SMC alone or APT were improved from the one-year outcome and were similar to CBT and GET at long-term follow-up, but these data should be interpreted in the context that additional therapies have been given based on physician choice and patient preference after the final assessment of the one-year trial |

| Wilshire, 2018 | These results raise serious questions about the robustness of the claims made about the efficacy of CBT and GET. The modest treatment effects obtained on self-report measures in the PACE trial do not outweigh, which could reasonably be explained by participant reporting biases. |

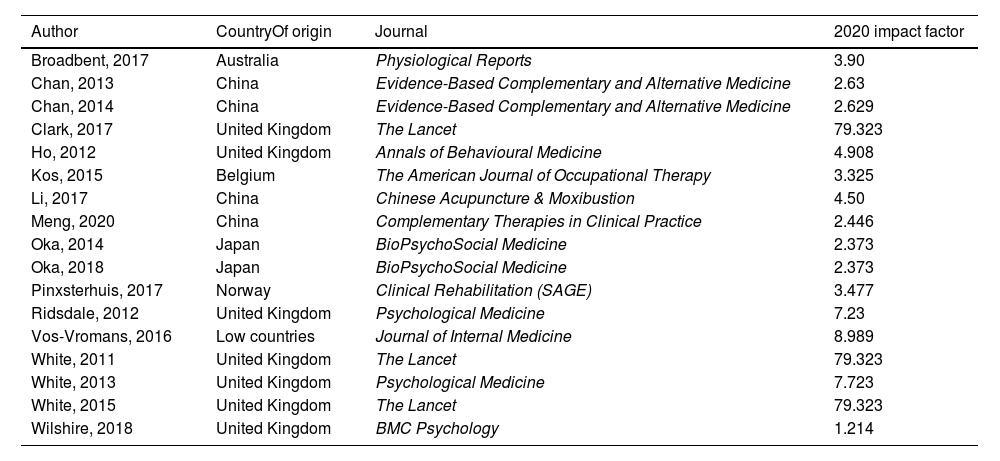

In addition, data were extracted regarding the quality of the RCT, the country in which it was conducted, and the impact factor of the published journal.

Quality assessmentThe studies were evaluated in alphabetical order of the surname of the main author, and when these coincided, they were ordered by year of publication.

The PEDro scale was used to assess the quality and validity of the RCTs.

Trials with a score equal to or greater than 5 were considered to be of high quality both internally and externally and were included in this review for data extraction.

Intervention efficacy and impactThe effectiveness of the interventions was assessed according to the significance data, considering significant results when p < .05, on the original data of the scientific articles. Moreover, to assess the clinical impact of the studies published in scientific journals, the impact factor (JCR) of the publication was also taken into account. For this purpose, data on JCR from 2020 was extracted from Web of Science (www.webofscience.com), and when this data was not available, the scientific journal's website and its metrics were searched (Table 3).

Origen of the study and journal impact factor.

| Author | CountryOf origin | Journal | 2020 impact factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broadbent, 2017 | Australia | Physiological Reports | 3.90 |

| Chan, 2013 | China | Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine | 2.63 |

| Chan, 2014 | China | Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine | 2.629 |

| Clark, 2017 | United Kingdom | The Lancet | 79.323 |

| Ho, 2012 | United Kingdom | Annals of Behavioural Medicine | 4.908 |

| Kos, 2015 | Belgium | The American Journal of Occupational Therapy | 3.325 |

| Li, 2017 | China | Chinese Acupuncture & Moxibustion | 4.50 |

| Meng, 2020 | China | Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice | 2.446 |

| Oka, 2014 | Japan | BioPsychoSocial Medicine | 2.373 |

| Oka, 2018 | Japan | BioPsychoSocial Medicine | 2.373 |

| Pinxsterhuis, 2017 | Norway | Clinical Rehabilitation (SAGE) | 3.477 |

| Ridsdale, 2012 | United Kingdom | Psychological Medicine | 7.23 |

| Vos-Vromans, 2016 | Low countries | Journal of Internal Medicine | 8.989 |

| White, 2011 | United Kingdom | The Lancet | 79.323 |

| White, 2013 | United Kingdom | Psychological Medicine | 7.723 |

| White, 2015 | United Kingdom | The Lancet | 79.323 |

| Wilshire, 2018 | United Kingdom | BMC Psychology | 1.214 |

From the PubMed, Cochrane and PEDro databases, the search explained above yielded 779 results. After reading the full text, 17 studies that met the eligibility criteria were finally included (Fig. 1). Of the selected studies, 10 were conducted in Europe, 6 in Asia and one in Oceania (Table 3).

Participant characteristics and case definition for inclusion criteriaA total of 3671 adult patients, aged 18–75 years, were enrolled in 17 RCTs. These 17 studies followed several inclusion methodologies according to the criteria: Fukuda 1994 (n = 11),14–23 Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2003 (n = 2),24,25 Oxford 1991 (n = 5),14,26–28 London 1994 (n = 1),25 Canadian criteria 2003 (n = 1),21 NICE 2015 (n = 1),24 International criteria 2011 (n = 1).21 There were also 2 RCTs29,30 that used their own criteria for the diagnosis of CFS.

Intervention plan characteristicsRegarding the interventions, the most common were graded exercise (GET) (n = 6),14,24–28 cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) (n = 6),23,25–29 Qigong exercise (n = 315,16,21 and adaptive stimulation therapy (APT) (n = 3).25–27 The other interventions applied to a lesser extent are self-guided graded exercise (SGE) (n = 1),24 transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TEAS) (n = 1),17 activity pace self-management (APSM) (n = 1),19 seated isometric yoga (n = 2),19,20 self-control therapy (n = 1),21 multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment (n = 123 and cupping (n = 1).30

Of the 17 studies selected, only the teams that performed GET, GES or MRT (n = 8) had a physiotherapist as part of the team. The rest of the research was carried out by healthcare personnel or experts in the therapy to be performed.

GES, APSM, Self control and APT therapies (n = 6) base their action protocol on a self-management booklet, while GET, Qigong, TEAS, isometric yoga, CBT, MRT and cupping treatments (n = 11) advocate the face-to-face participation of a therapist.

Measurement of outcomesOutcomes were assessed primarily using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Almost all studies included outcomes on fatigue and physical functioning, some on mental functioning, sleep, illness beliefs, pain, and global impressions of change. In total, 20 different PROM tools were applied. Most RCTs used multiple outcome measures both primary and secondary.

The Chandler Fatigue Scale (CFQ) was the most commonly used (n = 10), followed by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) (n = 9). Variables such as depression and anxiety were also studied with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (n = 4), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (n = 2), the Clinical Global Impressions scale (CGI) (n = 3) and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) (n = 3).

Fatigue was also measured using the Check List Individual Strength (CIS) (n = 2) and the Profile of Mood Status (POMS) (n = 2). In addition, there were numerous secondary variables within the selected investigations.

In addition to the POMS measures, 5 studies reported on objective outcome measures: indices of autonomic function and blood biomarkers (n = 314,20,22; an activity monitor bracelet (n = 1),24 and cardiopulmonary exercise testing (n = 1).29

Quality and validityAll but 320,25,27 of the studies included in this review scored 5 or higher on the PEDro scale, indicating optimal internal and external validity. Most studies were between 5 and 6, except for 222,23 which scored 7 and one30 which managed to score 8, the latter being the only study to be double-blind between study subjects and evaluators.

Interpretation of outcomes from randomised clinical trialsFive studies showed the effectiveness of GET therapy on various factors: blood count índices,15 fatigue,25,26,28,29 depression29 and physical function.25,28 The effects were maintained up to one year later. In addition, it was shown to be more effective for these variables than APT25,26 and SMC.14,25,26 However, when comparisons were made with other methodologies such as CBT or IE, no significance showed up in the results.

APT did not seem to be effective in any study when compared with CBT and GET, nor self-control therapy.21 In contrast, GES24 showed significance on fatigue and physical functioning compared to SMC.

Qigong exercise showed a significant decrease in fatigue values,15,16,22 depression,15 sleep quality16 and telomerase measurement22 compared to the measurements made at the beginning of the study.

APSM18 obtained significant improvements in fatigue and performance in the measurement made at study termination (3 weeks), compared to the one made at the beginning.

In turn, TEAS17 also achieved significant results in fatigue and psychological health compared to the control group at the end of the 4 weeks of intervention.

The cupping therapy30 demonstrated significant results in fatigue, anxiety, depression and sleep quality, for the 3 pressures studied compared to the measurements obtained at the beginning of the study, but without establishing significance between them.

Isometric yoga19,20 showed significant improvements in fatigue parameters, respiratory function and blood biomarkers at 2 months compared to baseline measurements, but not compared to the control group. IE30 also showed significance on blood biomarkers compared to UC, but was not significant when compared to GET.

MRT23 obtained significant improvements in fatigue and self-efficacy compared to CBT therapy. In turn, CBT showed significant results on fatigue25,26,29 and physical function25,27,28 compared to APT, SMC and the control group; but not when comparing the results with GET or MRT.

Furthermore, in many of the included investigations15,16,18–20 an improvement in the measured parameters (fatigue, physical function, etc.) of the control group can be seen at the end of the study compared to the first measurement of the same group.

DiscussionAetiology and pathophysiology of chronic fatigue syndromeRegarding genetic hypothesis, we observed that a family history of CFS significantly raises prevalence rates in members of the same family.

In addition to these factors, multiple infectious aetiologies are attributed to CFS, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpes virus (HHV-6), human parvovirus B19, Coxiella burnetii, giardiasis, West Nile virus, dengue virus, and even viral infections such as mononucleosis.1,3,4,8 Anti-HHV-6 IgM antibodies and HHV-6 antigens were also detected in peripheral blood.

Some authors studied cases of patients diagnosed with CFS/ME or fibromyalgia, who had recently been vaccinated against hepatitis B, relating them temporally.31

Also salient are the studies that identified immune deregulation as biomarkers, the most common being those that cause changes in B and T cell phenotypes and cytokine profiles, including changes in natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity.32

Along these lines, some authors have shown an increase in proinflammatory serum cytokines and have related their presence to the severity of the disease, correlating higher TGF-β and lower resistin levels with the severity of the symptoms, obtaining results of up to 17 cytokines with levels in CFS.33

It is noteworthy that Cook et al.34 showed that patients with CFS/ME have lower resting cerebral blood flow, differences in the connections between brain regions, alterations in the metabolism of the entire structure, reduced volume of grey and white matter, greater presence of lesions in white matter, increased neuroinflammation and altered brain function during cognition.

Chronic neuroinflammation of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus is currently being proposed as a critical factor in the perpetuation and relapses of CFS/ME.35

Long-COVID and chronic fatigue syndromeIn addition to the hypotheses raised here, the hypothesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome, caused by a coronavirus similar to the etiological agent of COVID-192 is also present. Currently, after overcoming the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2, many patients, mainly female, continue to report symptoms and even develop damage to vital organs or limbs.1,2,5

The research carried out by Lee et al.36 on the brains of deceased COVID-19 patients showed punctate hyperintensities that represented areas of microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage. These changes were also been found in patients with CFS.

The tissue damage resulting from this disease is accompanied fatigue as one of the main symptoms3,4,7 but other authors have described the symptoms as pain, anxiety, depression and poor sleep quality, "brain fog", shortness of breath and arrhythmias.

All these symptoms persist for months after the viral infection, indicating damage to vital or non-vital organs, and being characteristic of the aforementioned CFS.15,16

Furthermore, the latest research certifies that patients with 6 months of evolution with acute COVID-19, of a mild or moderate nature, met the criteria for CFS/ME, and the number of cases may have doubled as a result of the pandemic.37,38

Analysis of randomised clinical trial outcomesGET was shown to be a moderately effective therapy,14 in addressing short-, medium- and long-term fatigue,27 and short-term depression.26 GES therapy has the same scientific basis as GET, the main difference being the self-help booklet format.

Regarding the interventions with self-control therapy21 and seated isometric yoga,20 the former did not obtain significant findings, while the latter obtained improvements in fatigue, respiratory function and blood biomarkers at 2 months compared to measurements taken at baseline, but not compared to the control group.

However, the intervention with APT26 did not obtain significant results in any research while Qigong15,16 showed moderate efficacy in reducing post-treatment fatigue and an improvement in depression and sleep quality indices.

With regards to APSM,18 it was shown to be moderately effective in the sensation of fatigue, while the intervention with TEAS17 was also effective in post-treatment fatigue, without taking into account the PEM.

CBT26,29 demonstrated efficacy in fatigue and physical function when compared with other passive therapies, but not in studies that included another active therapy method such as GET or MRT. The latter therapy has shown improvements in fatigue levels and self-efficacy in the short and medium term.

ConclusionNo significant evidence currently exists on the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions in patients with CFS.

However, although the number of investigations in the treatment of CFS is increasing, the lack of consensus on diagnostic criteria hinders the development of a standardised treatment plan and, therefore of reliable comparison between studies.

Despite this, hypotheses on the aetiology and pathophysiology of CFS, together with advances in biomarkers, point to the need for a broader therapeutic approach.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.