The results of the SABER PRO medical test have considerable impact on the academic community. They are used as indicators of strengths and weaknesses of the education processes for both the student and the university. The wide variability of the results among different universities and students within the same university requires an analysis of the potential variables associated with the performance in these tests.

ObjectiveTo analyze the relationship of the inter-university variables and the inter-medical students variables against the performance on the SABER PRO tests.

Materials and MethodsThe information used was from 4498 medical students evaluated through the SABER PRO 2009 tests and of 40 schools of medicine the students belonged to. The association between the characteristics of the students and universities and the test scores obtained were evaluated using two-level hierarchical models.

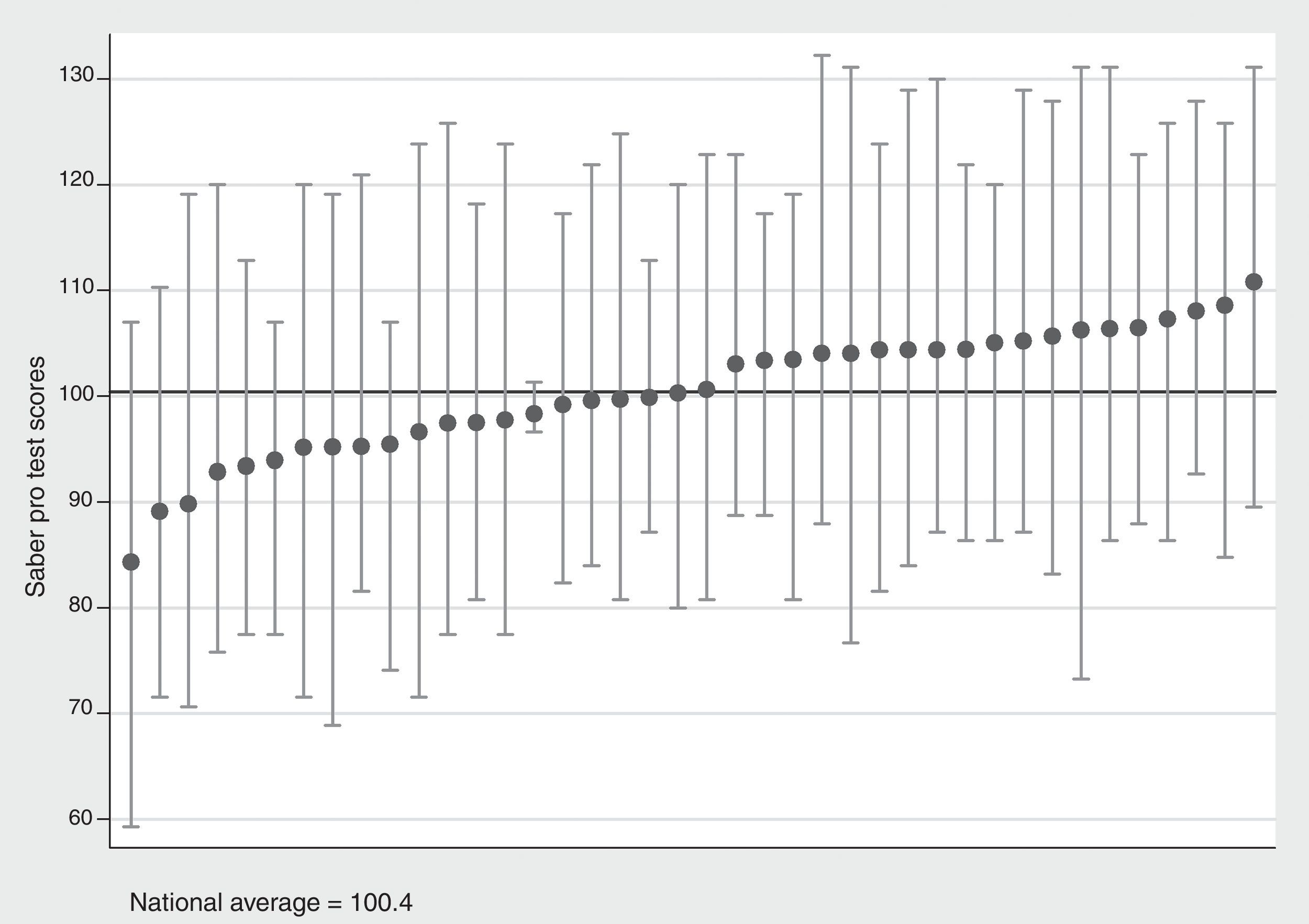

ResultsThe average score in the SABER PRO test per university for medical students was 100.4, with a range between 84.3 and 110.8 points. The variability of the test scores was accounted for in 29% of the cases by the inter-university differences.

ConclusionsThe public universities and the schools of medicine that have their own teaching hospital have better performance in average. However, the offer of medical specialization programs is associated with lower scores.

los resultados de las pruebas SABER PRO de medicina tienen un alto impacto en la comun idad académica a nivel de estudiante y de universidad, y son empleados como indicadores de fortalezas y debilidades de los procesos de formación. La amplia variabili dad de los resultados entre universidades y entre estudiantes dentro de las universidades hace necesario estudiar qué posibles variables están asociadas con el desempe¿no en estas pruebas.

Objetivoanalizar la relación entre las variables a nivel de las universidades y las variables a nivel de estudiante de medicina con el desempe¿no en las pruebas SABER PRO de estudiantes de medicina.

Materiales y métodosse empleó la información de 4.498 estudiantes de medicina evaluados en las pruebas SABER PRO 2009 y de las 40 facultades de medicina a las que pertenecían; mediante el uso de modelos jerárquicos de 2 niveles se evaluó la asociación de las caracte rísticas de estudiantes y universidades con el puntaje obtenido en la prueba.

Resultadosel puntaje promedio por universidades de la prueba SABER PRO 2009 para estu-diantes de medicina fue 100,4, con un rango entre 84,3 y 110,8 puntos. La variabilidad de los puntajes en la prueba fue explicada en un 29% por las diferencias entre universidades.

Conclusioneslas universidades oficiales y las facultades de medicina que cuentan con hospitales universitarios propios tienen en promedio mejores desempe¿nos. Sin embargo, la oferta de programas de especialización médica se asocia con menores puntajes.

A student's academic performance is an indicator of his/her future professional performance.1 In Colombia, a country with so many options in terms of university careers and with a broad range of programs and training strategies, the quality of academic programs should be questioned.2,3 With this consideration in mind, the State Higher Education Quality Exam (SABER PRO) (previously known as ECAES) was developed as a quality indicator of higher education. This test was regulated through Decree 3963 dated October 14, 20094 and became an additional requirement for graduation through Decree 4216 dated October 30, 2009.5 The Colombian Institute for the Evaluation of Education (ICFES) together with the National Ministry of Education (MEN) define the guidelines to design the SABER PRO tests, in accordance with the training by competencies policy, both at a university and a technical level. This test evaluates the competencies required from future higher education graduates and are developed with the on-going participation of academic communities, networks and associations of schools and programs. Some modules assess the general competencies of the students regardless of the training program, while others assess specific competencies, typical of certain groups of programs. These competencies are also assessed in other countries, i.e. the international project for Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes (AHELO).6 The medical SABER PRO tests are specifically designed with the involvement of the national academic community, including the associate and non-associate medical schools, through various national participation mechanisms under the leadership of the Colombian Association of Schools of Medicine (ASCOFAME). The goal is to design and reach agreement on the conceptual framework and the specifications of the test, based on the essential characteristics of professional medical training and the evaluation of experiences at the national and international level.7,8

The 2009 SABER PRO test had one single application and assessed distributed components in accordance with the life cycle, using 220 questions such as individual and family care, medical-legal actions, public health and environment, administrative actions and ethics and bioethics. Additionally, it included the evaluation of general competencies in English and reading comprehension using 45 and 15 questions, respectively.

The results of the SABER PRO tests have a high impact on the academic community in general, particularly Universities and professional associations; at the student level, academic programs and higher education institutions are used as indicators of strengths and weaknesses of their own training processes and educational projects, in addition to benchmarks against the national scenario.9 In terms of the test results, the broad inter-university variability observed, even when comparing intra-university students is remarkable. This fact leads to some questioning about the characteristics of the universities and schools of medicine associated with the performance of students on the test, and about the variables of the students related with the outcomes.

There is little research on the results of the SABER PRO tests and it is mainly based on the description of the results by components and the comparisons against the results obtained at the national level. Most are studies for the Program of Economics.10–16 The main findings showed higher SABER PRO scores in the day programs offered by the most important cities in the country and in the programs with less students. The relationship of the type of institution – private vs. public – and the scores is controversial; some surveys show differences, while others do not. Just one of these surveys15 makes a multi-level analysis considering the characteristics of the students and the universities in their respective domains and the results indicate that the variables that account for the best outcomes are the city where the institution is located, the type of institution and the modality.

Currently there are no studies on the results of the SABER PRO test in medicine and the association with the characteristics of the institution and the students. This paper analyzes the relationship between the structural variables of the universities and medical schools in the country and the medical students variables against the SABER PRO test performance, using hierarchical models and respecting the students nested structure within their own schools of medicine.

Materials and methodsThe data used in the study came from four different sources: the information provided by the students in the e-form to register for the test and the outcomes of the SABER PRO 2009 tests of the general and specific components for medicine, database available at ftp.icfes.gov.co (version 17/06/2011); the information on the qualified registry and quality accreditation of medical schools in the country that are part of the National Higher Education Information System (SNIES); the information on the registered research groups and their classification under the Colciencias Science and Technology System; and, complementary information on structure, professional associations and teaching-service agreements through direct contact with the schools of medicine.

The study was approved by the ethics and research committee of the School of Medicine of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

The outcomes variable for the analysis was the total score obtained in the SABER PRO test 2009, which is a normalized score with a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 10.

The students’ information included 13 variables: gender (female; male), age, marital status, socioeconomic level (1–2; 3–4; 5–6), occupation of father and mother (entrepreneur; employee; self-employed; retired; housewife; other), highest educational level of parents (none; elementary school; high school; technical diploma; professional; graduate degree), family monthly income (<1 minimum monthly wage; between 1 and <2 MMW; between 2 and >3 MMW; between 3 and <5 MMW; between 5 and >7 MMW and <10 MMW; >10 MMW), student breadwinner (yes; no), student with persons under his/her care (yes; no), current home address (regular; temporary), semester studied (10th or less; 11th; 12th), and working student (yes; no).

The university information gathered included 12 variables: private/public; type of institution (not a university/university); city (Bogotá, Medellín, Cali or Barranquilla/other); high quality program (yes/no); ASCOFAME member (yes/no); has its own teaching hospital (yes/no); number of Category A1 Research Groups; number of Category A research groups; number of Category C research groups; does the school offer medical specialization programs (yes/no); master programs (yes/no); PhD programs (yes/no). The variables of universities with medical schools in different campuses or cities were pooled in their headquarters since the individual information for each campus was not available, despite all the efforts to obtain such individualized information.

Given the hierarchical structure of university students (level 1 and level 2), a two-level linear model with random intercept was used.17 The statistical analysis was developed using the five steps described by Hox18 that include the analysis of the nil model, the construction of the model with independent level 1 and level 2 variables, and the construction and evaluation of the final model with the statistically significant variables found at each level. The level of significance used was 5% and the Stata statistical program (version 12.1) was used for multi-level model adjustment.

ResultsThe information of 4498 medical students from 40 universities in the country taking the SABER PRO 2009 exams was included. The average age of the students was 24.8 years (standard deviation SD 2.6 years); 55% were females and as a whole they belonged to socioeconomic levels 3 or 4; most of them were single (95.9%), were not the bread-winners (96.2%) or had any persons under their care (94.4%); in most cases, 63.8%, they were living in their regular home. 30.1% of their mothers were housewives, while their parents were mainly entrepreneurs (30.8%) or self-employed (25.2%). Family income ranged mostly between 3 and less than 5 minimum monthly wages and 15.8% of the households had incomes below 2 MMW. Only 10% reported income above 10 MMW.

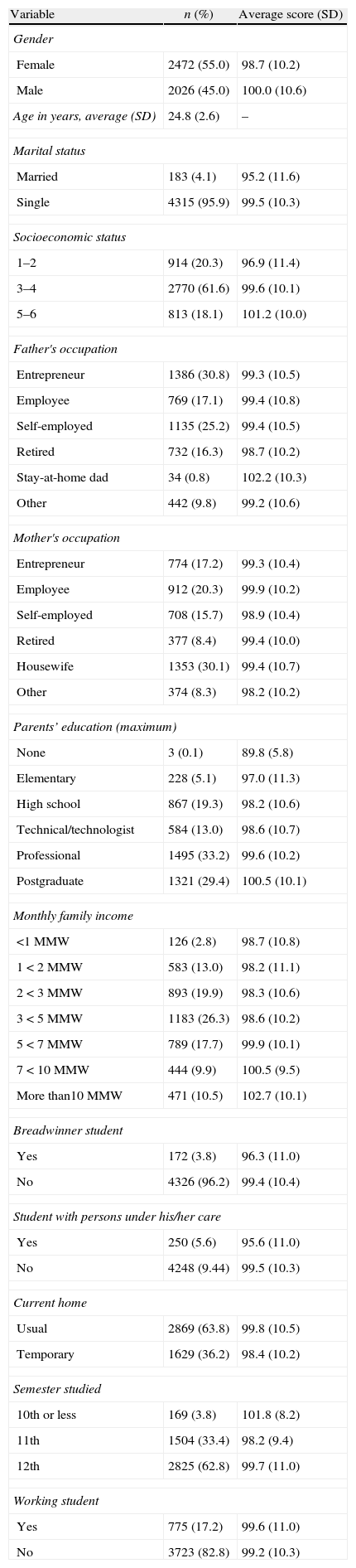

62.6% of parents were university graduates with post-graduate diploma. Most of the students assessed in this application of the test were in their 12th semester (62.8%), only 3.8% were in 10th semester or below. Although 17.2% of the students indicated that they were working students, 12.1% of them worked because it was a career requirement and 2.7% worked to gain experience and earn some pocket money. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the students and the respective average results of the tests. The highest scores were obtained by males in the 5th and 6th social strata, by children of parents with a post-graduate degree and by students from households with over 10MMW.

Characteristics of the students assessed using the SABER PRO 2009 test for medicine and test average scores.

| Variable | n (%) | Average score (SD) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 2472 (55.0) | 98.7 (10.2) |

| Male | 2026 (45.0) | 100.0 (10.6) |

| Age in years, average (SD) | 24.8 (2.6) | – |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 183 (4.1) | 95.2 (11.6) |

| Single | 4315 (95.9) | 99.5 (10.3) |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| 1–2 | 914 (20.3) | 96.9 (11.4) |

| 3–4 | 2770 (61.6) | 99.6 (10.1) |

| 5–6 | 813 (18.1) | 101.2 (10.0) |

| Father's occupation | ||

| Entrepreneur | 1386 (30.8) | 99.3 (10.5) |

| Employee | 769 (17.1) | 99.4 (10.8) |

| Self-employed | 1135 (25.2) | 99.4 (10.5) |

| Retired | 732 (16.3) | 98.7 (10.2) |

| Stay-at-home dad | 34 (0.8) | 102.2 (10.3) |

| Other | 442 (9.8) | 99.2 (10.6) |

| Mother's occupation | ||

| Entrepreneur | 774 (17.2) | 99.3 (10.4) |

| Employee | 912 (20.3) | 99.9 (10.2) |

| Self-employed | 708 (15.7) | 98.9 (10.4) |

| Retired | 377 (8.4) | 99.4 (10.0) |

| Housewife | 1353 (30.1) | 99.4 (10.7) |

| Other | 374 (8.3) | 98.2 (10.2) |

| Parents’ education (maximum) | ||

| None | 3 (0.1) | 89.8 (5.8) |

| Elementary | 228 (5.1) | 97.0 (11.3) |

| High school | 867 (19.3) | 98.2 (10.6) |

| Technical/technologist | 584 (13.0) | 98.6 (10.7) |

| Professional | 1495 (33.2) | 99.6 (10.2) |

| Postgraduate | 1321 (29.4) | 100.5 (10.1) |

| Monthly family income | ||

| <1 MMW | 126 (2.8) | 98.7 (10.8) |

| 1<2 MMW | 583 (13.0) | 98.2 (11.1) |

| 2<3 MMW | 893 (19.9) | 98.3 (10.6) |

| 3<5 MMW | 1183 (26.3) | 98.6 (10.2) |

| 5<7 MMW | 789 (17.7) | 99.9 (10.1) |

| 7<10 MMW | 444 (9.9) | 100.5 (9.5) |

| More than10 MMW | 471 (10.5) | 102.7 (10.1) |

| Breadwinner student | ||

| Yes | 172 (3.8) | 96.3 (11.0) |

| No | 4326 (96.2) | 99.4 (10.4) |

| Student with persons under his/her care | ||

| Yes | 250 (5.6) | 95.6 (11.0) |

| No | 4248 (9.44) | 99.5 (10.3) |

| Current home | ||

| Usual | 2869 (63.8) | 99.8 (10.5) |

| Temporary | 1629 (36.2) | 98.4 (10.2) |

| Semester studied | ||

| 10th or less | 169 (3.8) | 101.8 (8.2) |

| 11th | 1504 (33.4) | 98.2 (9.4) |

| 12th | 2825 (62.8) | 99.7 (11.0) |

| Working student | ||

| Yes | 775 (17.2) | 99.6 (11.0) |

| No | 3723 (82.8) | 99.2 (10.3) |

Score: SABER PRO test result; SD: standard deviation; MMW: minimum monthly wage.

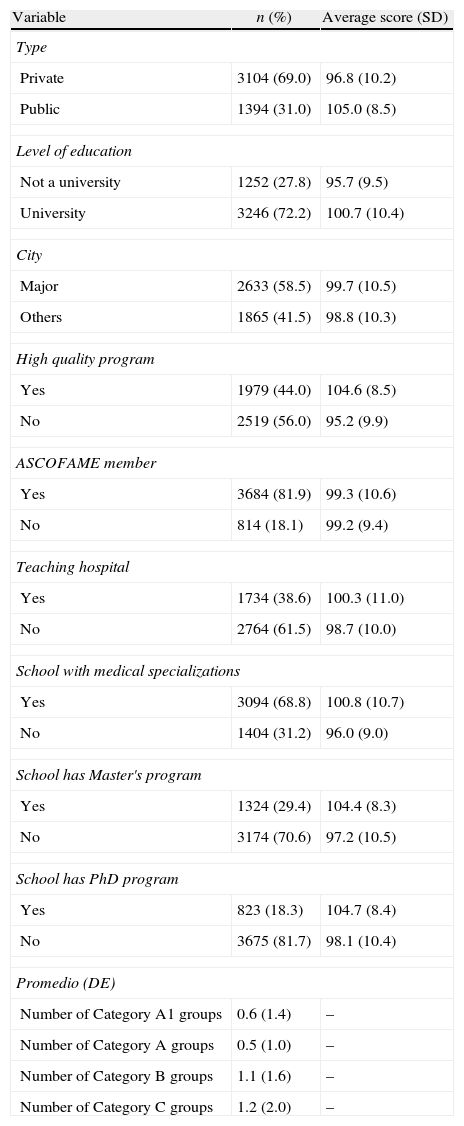

69.0% of the educational institutions were public, and most of them were universities (72.2%). 58.5% were located in Bogotá, Medellin, Cali or Barranquilla. With regard to the schools of medicine, only 44.0% of the academic programs had quality accreditation; 81.9% were ASCOFAME members; 38.6% had their own university hospital for their students to practice. The graduate programs offered by these medical schools included medical specialties, master's degrees and PhDs in 68.8%, 29.4% and 18.3%, respectively. 37.5% of the schools had Category A1 or A research groups and 65.0% had Category B or C groups. Table 2 summarizes the variables of the educational institutions and the average test results. The public institutions, universities, schools with accredited quality programs, schools with their own university hospitals and medical schools offering graduate programs exhibit the highest average scores.

Characteristics of the educational institutions participating in the SABER PRO 2009 test for medicine and average test scores.

| Variable | n (%) | Average score (SD) |

| Type | ||

| Private | 3104 (69.0) | 96.8 (10.2) |

| Public | 1394 (31.0) | 105.0 (8.5) |

| Level of education | ||

| Not a university | 1252 (27.8) | 95.7 (9.5) |

| University | 3246 (72.2) | 100.7 (10.4) |

| City | ||

| Major | 2633 (58.5) | 99.7 (10.5) |

| Others | 1865 (41.5) | 98.8 (10.3) |

| High quality program | ||

| Yes | 1979 (44.0) | 104.6 (8.5) |

| No | 2519 (56.0) | 95.2 (9.9) |

| ASCOFAME member | ||

| Yes | 3684 (81.9) | 99.3 (10.6) |

| No | 814 (18.1) | 99.2 (9.4) |

| Teaching hospital | ||

| Yes | 1734 (38.6) | 100.3 (11.0) |

| No | 2764 (61.5) | 98.7 (10.0) |

| School with medical specializations | ||

| Yes | 3094 (68.8) | 100.8 (10.7) |

| No | 1404 (31.2) | 96.0 (9.0) |

| School has Master's program | ||

| Yes | 1324 (29.4) | 104.4 (8.3) |

| No | 3174 (70.6) | 97.2 (10.5) |

| School has PhD program | ||

| Yes | 823 (18.3) | 104.7 (8.4) |

| No | 3675 (81.7) | 98.1 (10.4) |

| Promedio (DE) | ||

| Number of Category A1 groups | 0.6 (1.4) | – |

| Number of Category A groups | 0.5 (1.0) | – |

| Number of Category B groups | 1.1 (1.6) | – |

| Number of Category C groups | 1.2 (2.0) | – |

SD: standard deviation; ASCOFAME: Asociación Colombiana de Facultades de Medicina (Colombian Association of Medical Schools).

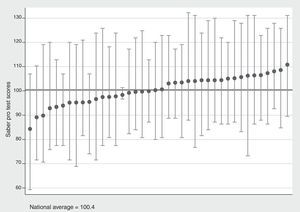

The average SABER PRO 2009 test score by university for medical students was 100.4 (out of 5.9), ranging between 84.3 and 110.8 points. Fig. 1 illustrates the test scores average and range per educational institution, indicating intra-institution variability and scatter of the scores.

The two-level hierarchical model for the nil model (intercept only) indicates a significant inter-university variability (or university-related variability) (SD 5.8 95% CI [4.7; 7.3]), in addition to a significant student variability within the same university (intra-university variability or student-related variability) (SD 8.2; 95%CI [8.0; 8.4]). The inter-class correlation coefficient (rho) of 0.34 justifies the use of hierarchical models to explain the residual variability among universities and students.

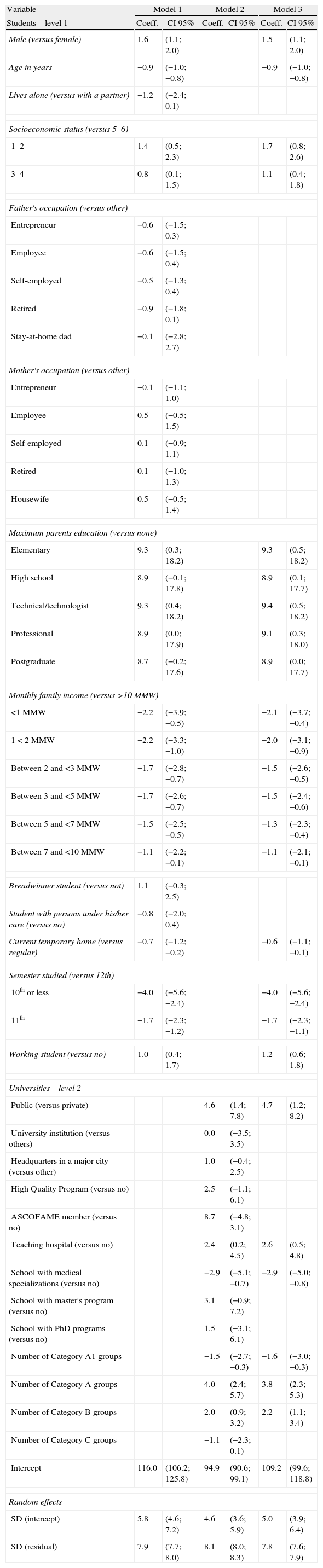

Table 3 shows the results of the hierarchical models sequentially adjusted. The first adjusted model with the variables at the student level indicates differences in terms of gender, age, economic status, maximum educational level of parents, living outside their usual environment and semester studied at the time of taking the test; however, the decline in inter- and intra-university variability was small, as shown by the intra-class correlation coefficient in this model (rho=0.35). Model 2 adjusted for university variables indicates differences based on whether the institution was public or private, having a university hospital, offering medical specialization programs and the number of Category A1, A and B research groups; the inter-university variability declines but with no impact on the intra-university variability, with an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.24. Adjusting model 3 according to the significant variables in the previous models, there are still statistically significant differences preserving the same signs of differences in the test scores, further reducing the inter-university variability, accounting for 29.0% of inter-university variability (rho=0.29).

Association of the SABER PRO 2009 test results for medicine with the student and university-related variables using two-level linear hierarchical models.

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| Students – level 1 | Coeff. | CI 95% | Coeff. | CI 95% | Coeff. | CI 95% |

| Male (versus female) | 1.6 | (1.1; 2.0) | 1.5 | (1.1; 2.0) | ||

| Age in years | −0.9 | (−1.0; −0.8) | −0.9 | (−1.0; −0.8) | ||

| Lives alone (versus with a partner) | −1.2 | (−2.4; 0.1) | ||||

| Socioeconomic status (versus 5–6) | ||||||

| 1–2 | 1.4 | (0.5; 2.3) | 1.7 | (0.8; 2.6) | ||

| 3–4 | 0.8 | (0.1; 1.5) | 1.1 | (0.4; 1.8) | ||

| Father's occupation (versus other) | ||||||

| Entrepreneur | −0.6 | (−1.5; 0.3) | ||||

| Employee | −0.6 | (−1.5; 0.4) | ||||

| Self-employed | −0.5 | (−1.3; 0.4) | ||||

| Retired | −0.9 | (−1.8; 0.1) | ||||

| Stay-at-home dad | −0.1 | (−2.8; 2.7) | ||||

| Mother's occupation (versus other) | ||||||

| Entrepreneur | −0.1 | (−1.1; 1.0) | ||||

| Employee | 0.5 | (−0.5; 1.5) | ||||

| Self-employed | 0.1 | (−0.9; 1.1) | ||||

| Retired | 0.1 | (−1.0; 1.3) | ||||

| Housewife | 0.5 | (−0.5; 1.4) | ||||

| Maximum parents education (versus none) | ||||||

| Elementary | 9.3 | (0.3; 18.2) | 9.3 | (0.5; 18.2) | ||

| High school | 8.9 | (−0.1; 17.8) | 8.9 | (0.1; 17.7) | ||

| Technical/technologist | 9.3 | (0.4; 18.2) | 9.4 | (0.5; 18.2) | ||

| Professional | 8.9 | (0.0; 17.9) | 9.1 | (0.3; 18.0) | ||

| Postgraduate | 8.7 | (−0.2; 17.6) | 8.9 | (0.0; 17.7) | ||

| Monthly family income (versus >10 MMW) | ||||||

| <1 MMW | −2.2 | (−3.9; −0.5) | −2.1 | (−3.7; −0.4) | ||

| 1<2 MMW | −2.2 | (−3.3; −1.0) | −2.0 | (−3.1; −0.9) | ||

| Between 2 and <3 MMW | −1.7 | (−2.8; −0.7) | −1.5 | (−2.6; −0.5) | ||

| Between 3 and <5 MMW | −1.7 | (−2.6; −0.7) | −1.5 | (−2.4; −0.6) | ||

| Between 5 and <7 MMW | −1.5 | (−2.5; −0.5) | −1.3 | (−2.3; −0.4) | ||

| Between 7 and <10 MMW | −1.1 | (−2.2; −0.1) | −1.1 | (−2.1; −0.1) | ||

| Breadwinner student (versus not) | 1.1 | (−0.3; 2.5) | ||||

| Student with persons under his/her care (versus no) | −0.8 | (−2.0; 0.4) | ||||

| Current temporary home (versus regular) | −0.7 | (−1.2; −0.2) | −0.6 | (−1.1; −0.1) | ||

| Semester studied (versus 12th) | ||||||

| 10th or less | −4.0 | (−5.6; −2.4) | −4.0 | (−5.6; −2.4) | ||

| 11th | −1.7 | (−2.3; −1.2) | −1.7 | (−2.3; −1.1) | ||

| Working student (versus no) | 1.0 | (0.4; 1.7) | 1.2 | (0.6; 1.8) | ||

| Universities – level 2 | ||||||

| Public (versus private) | 4.6 | (1.4; 7.8) | 4.7 | (1.2; 8.2) | ||

| University institution (versus others) | 0.0 | (−3.5; 3.5) | ||||

| Headquarters in a major city (versus other) | 1.0 | (−0.4; 2.5) | ||||

| High Quality Program (versus no) | 2.5 | (−1.1; 6.1) | ||||

| ASCOFAME member (versus no) | 8.7 | (−4.8; 3.1) | ||||

| Teaching hospital (versus no) | 2.4 | (0.2; 4.5) | 2.6 | (0.5; 4.8) | ||

| School with medical specializations (versus no) | −2.9 | (−5.1; −0.7) | −2.9 | (−5.0; −0.8) | ||

| School with master's program (versus no) | 3.1 | (−0.9; 7.2) | ||||

| School with PhD programs (versus no) | 1.5 | (−3.1; 6.1) | ||||

| Number of Category A1 groups | −1.5 | (−2.7; −0.3) | −1.6 | (−3.0; −0.3) | ||

| Number of Category A groups | 4.0 | (2.4; 5.7) | 3.8 | (2.3; 5.3) | ||

| Number of Category B groups | 2.0 | (0.9; 3.2) | 2.2 | (1.1; 3.4) | ||

| Number of Category C groups | −1.1 | (−2.3; 0.1) | ||||

| Intercept | 116.0 | (106.2; 125.8) | 94.9 | (90.6; 99.1) | 109.2 | (99.6; 118.8) |

| Random effects | ||||||

| SD (intercept) | 5.8 | (4.6; 7.2) | 4.6 | (3.6; 5.9) | 5.0 | (3.9; 6.4) |

| SD (residual) | 7.9 | (7.7; 8.0) | 8.1 | (8.0; 8.3) | 7.8 | (7.6; 7.9) |

Coeff.: regression coefficient calculator; DE: standard deviation of the regression coefficient calculator; Model 1: model with student-related variables; Model 2: model with university-related variables; Model 3: model with significant student and university-related variables; MMW: minimum monthly salary; ASCOFAME: Colombian Association of Medical Schools.

This is the first study to analyze the inter-university variability factors in the results of the SABER PRO medical tests, as well as the inter-student variability in each university. This is an area rarely studied and deserves additional investigation due to the peculiarities in the training of medical professionals, beyond the development of quality indexes for inter-institution comparisons.19 Another strength of the study has to do with information analysis using hierarchical models, respecting the hierarchical structure of the students within the universities.

The student findings are consistent with other studies on education in Colombia at the level of elementary and high school education and are also consistent with other studies on the SABER PRO tests in other university training programs. In terms of the demographic variables related to the test scores, males in average score higher than females; this characteristic is also present in the outcomes of tests such as “saber 11”,20 PISA21 and SABER PRO for Economics.15 A similar situation occurs with younger students that achieve higher scores. With regard to the socioeconomic variables, an interesting result is seen in terms of the impact of the socioeconomic status, where the lower strata accomplish higher scores as opposed to what happens with other research at the high school level.22 This may be due to the fact that most of these students attend public universities that accomplish the highest scores in these tests. However, family income did show a positive correlation with the test performance. The effect of parents on the student's performance is unrelated to their occupation, but is related to the level of education, as established for high school and university education23; hence, parents with higher academic levels have a greater impact on the vocational level of their children and translate into improved academic performance. The expectation that other characteristics of the students such as being the breadwinner or having people under their care could have a negative impact, proved to be wrong and showed no significant association, probably because of the low frequency of these factors among the students analyzed. Likewise, a lower performance was expected from working students because of need to spend more time doing other things rather than studying; however, the results show exactly the opposite but it could due to the fact that 70% of working students are working as part of their career training requirements. Finally, students in their last academic semester had the best outcomes, probably due to more mature and integrated knowledge, in addition to more experience and exposure to heath care practices.

Public universities showed better performance as compared to private and this can be explained by the relationship with the socioeconomic status of the student; Valens15 explains this finding as a potential bias in the selection of the students admitted to public institutions because of the stringent admission criteria where only the best are usually admitted. The city where the medical program is provided was not related to the test results; this is encouraging and could be a marker of social equity.

One of the major strengths of this paper was the inclusion of university variables that are not present in the test registration form, expanding the evaluation of such characteristics to other traits of medical education such as being an ASCOFAME member, being a high-quality accredited program,24 having a teaching hospital for practicing physicians, the availability of graduate programs and information about research groups recognized under the Science and Technology System – Colciencias. No association was established between the test outcomes and having an accredited quality program or being an ASCOFAME member – 81.9% of the universities are members of ASCOFAME and the rest are working toward being admitted. In contrast, having a teaching hospital was definitely associated with higher scores, although this fact was not considered in other research projects but presupposes a stronger integration between the theory and the practice of medicine, increased institutional identity and curricular integrity.

Offering graduate programs in the medical schools only showed significant association with the medical specialization programs, but surprisingly enough had a negative impact on the average score per institution, i.e. the institutions with graduate programs have a lower score. Similarly, having Category A1 groups is negatively associated with the test outcomes, while having Category A and B groups is associated with higher scores. There is no research to support or contrast these findings and hence we may only hypothesize and encourage further studies; in contrast to the general practitioner, students from schools with medical specializations are more strongly oriented to pursue future specialized medical training and highly value the knowledge required for those specialties.

According to the nil model – not controlling other variables – 34% of the variance in the outcomes of the students taking the SABER PRO test is accounted for by the university they belong to. In this study, the two-level hierarchical model adjusted for the significant student and university variables was able to reduce this variability to 29%. However, such reduction is insignificant when compared to the study with students of Economics (from 39% to 27%),15 and leads to the conclusion that the performance in the medical test depends on several additional variables beyond the scope of this study, despite the efforts to expand the information on structure and infrastructure of the universities/schools of medicine. The information available through the test registration form is limited, general and unspecific; hence, any future analysis should collect university information involving aspects such as the number of professors, their academic training and the professors-to-students ratio. Access to these indicators is difficult and they were excluded from this paper because of the low response rate of the survey submitted to the schools of medicine. The suggestion is to implement a national registry of universities, similar to the National Information System for Elementary and High School Education (SINEB). Any future research efforts may also consider variables to assess the information actually received by students on the epidemiological profile and the curricular teaching methodologies, such as problem solving-based learning and evidence-based medicine, inter alia.8,25

Finally, one weakness to be underscored is the fact that the information from universities/schools of medicine used in the study corresponds to 2009 as the last training period of the students. This may not be consistent with the current characteristics or the impact on the professional training of the students assessed. Moreover, the information used could be biased since the students themselves provided it when registering for the test.

FundingThe study was financed with resources provided by ICFES – Colciencias (Code: 1203-518-28148) and the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

We would like to acknowledge Mabelin Villareal, research assistant, for helping with data management.

We would also like to thank The Colombian Association of Schools of Medicine (ASCOFAME), particularly Dr. Ricardo Rozo, Executive Director and Adriana Parra, Assistant to the Executive Director for their assistance in contacting the Deans of Medicine that made available the information about the universities.

Please cite this article as: Gil FA, et al. Impacto de las facultades de medicina y de los estudiantes sobre los resultados en la prueba nacional de calidad de la educación superior (SABER PRO). Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rca.2013.04.003