Perioperative hypothermia is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Consequently, surgical patient temperature should be the fundamental concern but, nonetheless, it is still the least valued physiological parameter.

ObjectivesTo assess temperature management during the perioperative period and determine the frequency of inadvertent hypothermia and related factors.

Materials and methodsProspective observational study in adult patients scheduled for surgical procedure with anesthesia time ≥30min. Hypothermia is defined as a forehead skin temperature ≤35.9°C. The null hypothesis of no difference between patients with normothermia and hypothermia was proposed. Comparison of quantitative variables was analyzed with the Student “t” test, and the Chi square was used for the qualitative variables. The analysis was followed by a logistic regression analysis.

ResultsWe included 167 consecutive patients; intraoperative monitoring of temperature was used in 10% of patients, and the use of warm intravenous fluids and forced air heating in 78% and 63%, respectively. The frequency of inadvertent hypothermia was 56.29%, associated with age ≥65 years, female gender and BMI≥30kg/m2. This last variable might have been influenced by the method of temperature measurement.

ConclusionWarming measures without temperature monitoring do not result in the desired effect. The high frequency of inadvertent hypothermia requires action guidelines for prevention and management, especially in high-risk patients who, in this study, were patients≥65 years of age and females.

La hipotermia perioperatoria está asociada con mayor morbimortalidad, por lo que la temperatura del paciente quirúrgico debería ser una preocupación fundamental; sin embargo, es el parámetro fisiológico menos valorado.

ObjetivosEvaluar el manejo de la temperatura en el perioperatorio, determinar la frecuencia de hipotermia inadvertida y los factores relacionados.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo observacional en pacientes adultos programados para procedimiento quirúrgico con tiempo ≥ 30 min de anestesia. La hipotermia se definió como una temperatura de la piel de la frente ≤ 35,9°C. Se planteó la hipótesis nula de no diferencia entre los pacientes con normotermia e hipotermia. La comparación de las variables cuantitativas fue analizada con la prueba t de Student y las cualitativas con la prueba del Chi cuadrado, y después se realizó un análisis de regresión logística.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 167 pacientes consecutivos; la monitorización intraoperatoria de la temperatura se usó en el 10% de los pacientes, el uso de líquidos intravenosos tibios y calentamiento con aire forzado en el 78 y el 63%, respectivamente. La frecuencia de hipotermia inadvertida fue del 56,29%, asociada a edad ≥ 65 años, sexo femenino e índice de masa corporal ≥ 30kg/m2. Esta última variable podría estar influenciada por el método de medición de la temperatura.

ConclusionesLas medidas de calentamiento sin monitorización de la temperatura no tienen el efecto esperado. La frecuencia elevada de hipotermia inadvertida hace necesaria una guía de actuación de prevención y manejo en especial en pacientes de riesgo, que en este estudio fueron edad ≥ 65 años y sexo femenino.

There is evidence that hypothermia is associated with systemic complications1–6 and alters the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of anesthetic agents.7–11 The most frequent perioperative thermoregulation alteration is inadvertent hypothermia.12 The reported incidence varies greatly between 6% and 90%13–17 depending on the type of surgery, and it is associated with a high potential for complications,1 including increased blood loss,2,3 morbid cardiac events,4 compromised healing and surgical wound infection,5,6 and higher mortality.18

Intraoperative temperature monitoring became popular starting in the 1960s, and even more than 50 years later this physiological parameter is still not monitored rigorously or managed by the anesthetist, despite the knowledge that adequate treatment improves the final outcome for the surgical patient.19,20

Few recommendations are available regarding temperature. The 2007 guidelines of the American College of Cardiology on perioperative cardiovascular care and assessment for non-cardiac surgery recommend maintenance of perioperative normothermia on the basis of Class I (level B) evidence.21 The guidelines of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)22 mention temperature very briefly: “temperature must be assessed periodically during recovery from anesthesia”. In England, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), published in 2008 some guidelines for the management of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia, including recommendations for its adequate management throughout the whole preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative period.23

The objective of the study was to assess temperature management during the perioperative period and determine the frequency of inadvertent hypothermia and associated factors.

Materials and methodsThe protocol for this prospective observational study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the University Hospital Complex in Cartagena-Murcia, Spain. Adult patients coming for any type of elective surgery under different anesthetic techniques lasting more than 30min were included consecutively in the study. Obstetric and pediatric patients were excluded.

The following were the data collected in the study: sex, age in years, weight in kilograms, height in centimeters, body mass index (BMI), ASA classification, surgical specialty, anesthesia time and type, use of temperature monitoring, use of warm intravenous fluids and of forced-air warming systems during surgery, and clinical manifestations of hypothermia in the recovery room. Patients were divided into two age groups – under 65 years of age and 65 or more. BMI was classified as lower than 30kg/m2 and equal to or greater than 30kg/m2. Forehead skin temperature was recorded as soon as patients were brought to the recovery room and 1h later, considering that patient stay in the recovery room is usually longer than 1h but shorter than 2h. Using or not using intraoperative temperature monitoring, and the techniques used to maintain temperature were left to the discretion of the anesthetist, and that information was gathered verbally from the anesthesia team upon arrival of the patient to the recovery room. During the study, it was decided not to inform the anesthetists about the follow-up conducted in the recovery room in order not to induce changes in monitoring behavior or in their strategies for managing temperature. Clinical manifestations of hypothermia during the stay in the recovery room were recorded.

Reusable or disposable sensors of the Ohmeda Aestiva 3000 anesthesia machine were used in those cases where intraoperative temperature was measured, with inferior or nasopharyngeal recording. The Bair Huggers 750 and 775 units were used in those cases where forced-air warming (blanket/mattress) was used. Intravenous fluids were warmed in thermostatic baths for water (Precisterm P Selecta) at a temperature of 40°C.

Temperature was measured in the recovery room at 5cm from the forehead skin surface using a PCE-FIT 10 (PCE Deutschland GmbH, accuracy ±0.2°C in the 36–39°C range, and ±0.3°C in the 32–35.9°C range, measurement range 32–42.4°C), which is the device available in this area. The device was maintained and calibrated according to the manufacturer's instructions in order to obtain a temperature reading equivalent to central temperature.

Hypothermia was defined as a temperature equal to or lower than 35.9°C at three levels: mild hypothermia, 35–35.9°C; moderate hypothermia, 34–34.9°C; and severe hypothermia, ≤33.9°C.17

The sample was selected on a convenience basis. For the statistical tests, the null hypothesis of no difference between normothermic patients and patients with hypothermia on arrival to the recovery room was proposed. Quantitative variables were compared using the Student “t” test, and qualitative variables were compared using the Chi square test. After the comparison, a multivariate analysis (binary logistic regression) was applied, including variables for which a p value equal to or lower than 0.08 was obtained; moreover, polytomic variables were converted to the dichotomic form. Data were analyzed using the statistical package SPSS, version 12 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and an Excel worksheet, version 12 (Microsoft Corporation). All tests with a p<0.05 were considered.

ResultsData were obtained from 200 consecutive patients. Of those, 33 were excluded because of incomplete information, for a final number of 167 included in the statistical analysis.

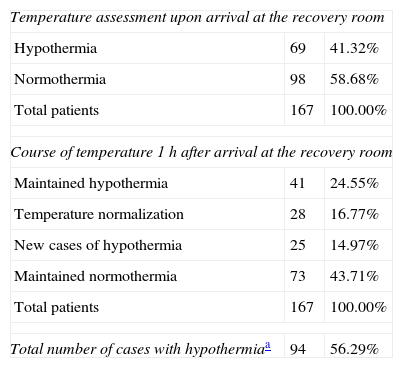

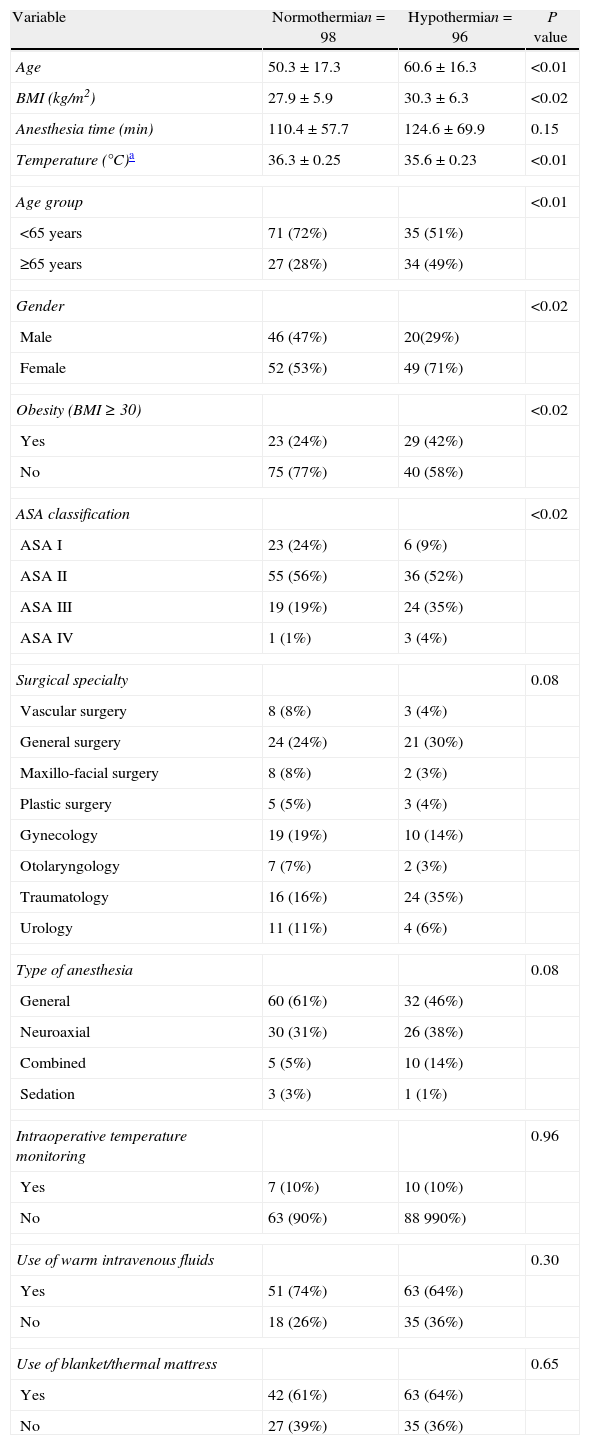

Hypothermia was observed in 56.29% of the patients (94/167), in 41.32% at the time of arrival at the recovery room, and in 14.97% 1h into their stay in this area. Table 1 shows the course of the temperature. Of the patients who presented with hypothermia on arrival to the recovery room, 68 (40.72%) had mild hypothermia and 1 (0.6%), an 89-year-old patient, had moderate hypothermia. The age range was 17–89 years. When patient characteristics were compared in the bivariate analysis, significant (p<0.02) differences were found between the normothermia and hypothermia groups in terms of age, sex, obesity (BMI≥30) and ASA classification. For the logistic regression, the surgical specialty and the type of anesthesia were also included because of a p=0.08 (Table 2).

Presence of inadvertent hypothermia.

| Temperature assessment upon arrival at the recovery room | ||

| Hypothermia | 69 | 41.32% |

| Normothermia | 98 | 58.68% |

| Total patients | 167 | 100.00% |

| Course of temperature 1h after arrival at the recovery room | ||

| Maintained hypothermia | 41 | 24.55% |

| Temperature normalization | 28 | 16.77% |

| New cases of hypothermia | 25 | 14.97% |

| Maintained normothermia | 73 | 43.71% |

| Total patients | 167 | 100.00% |

| Total number of cases with hypothermiaa | 94 | 56.29% |

Characteristics of the subjects studied.

| Variable | Normothermian=98 | Hypothermian=96 | P value |

| Age | 50.3±17.3 | 60.6±16.3 | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.9±5.9 | 30.3±6.3 | <0.02 |

| Anesthesia time (min) | 110.4±57.7 | 124.6±69.9 | 0.15 |

| Temperature (°C)a | 36.3±0.25 | 35.6±0.23 | <0.01 |

| Age group | <0.01 | ||

| <65 years | 71 (72%) | 35 (51%) | |

| ≥65 years | 27 (28%) | 34 (49%) | |

| Gender | <0.02 | ||

| Male | 46 (47%) | 20(29%) | |

| Female | 52 (53%) | 49 (71%) | |

| Obesity (BMI≥30) | <0.02 | ||

| Yes | 23 (24%) | 29 (42%) | |

| No | 75 (77%) | 40 (58%) | |

| ASA classification | <0.02 | ||

| ASA I | 23 (24%) | 6 (9%) | |

| ASA II | 55 (56%) | 36 (52%) | |

| ASA III | 19 (19%) | 24 (35%) | |

| ASA IV | 1 (1%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Surgical specialty | 0.08 | ||

| Vascular surgery | 8 (8%) | 3 (4%) | |

| General surgery | 24 (24%) | 21 (30%) | |

| Maxillo-facial surgery | 8 (8%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Plastic surgery | 5 (5%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Gynecology | 19 (19%) | 10 (14%) | |

| Otolaryngology | 7 (7%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Traumatology | 16 (16%) | 24 (35%) | |

| Urology | 11 (11%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Type of anesthesia | 0.08 | ||

| General | 60 (61%) | 32 (46%) | |

| Neuroaxial | 30 (31%) | 26 (38%) | |

| Combined | 5 (5%) | 10 (14%) | |

| Sedation | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Intraoperative temperature monitoring | 0.96 | ||

| Yes | 7 (10%) | 10 (10%) | |

| No | 63 (90%) | 88 990%) | |

| Use of warm intravenous fluids | 0.30 | ||

| Yes | 51 (74%) | 63 (64%) | |

| No | 18 (26%) | 35 (36%) | |

| Use of blanket/thermal mattress | 0.65 | ||

| Yes | 42 (61%) | 63 (64%) | |

| No | 27 (39%) | 35 (36%) | |

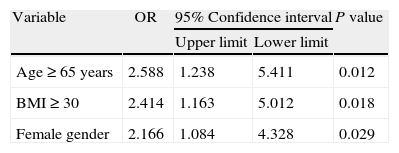

The following were the independent factors related to hypothermia resulting from the binary logistic regression analysis: age group greater or equal to 65 years, BMI greater or equal to 30kg/m2, and female gender, all with a p<0.03 (Table 3).

Regarding intraoperative temperature management, it was found that temperature was monitored in 10% of patients and that the warming methods used were warm intravenous fluids in 78% and a forced-air warming system in 63% of patients, with no statistically significant difference between normothermic patients and those with hypothermia (Table 2). No patient with neuroaxial anesthesia was monitored intraoperatively. No relationship was found between temperature management measures and the presence of risk factors for hypothermia such as ASA and/or age extremes, or the use of warm fluids and/or warming with forced air.

During their stay in the recovery room, 9% (15/167) of the patients reported feeling cold and/or were found to be shivering, and they were managed using forced-air warming blankets. This method was used in one patient who was found to be hyporthermic but with no clinical manifestations.

DiscussionThis study found a high percentage (56.29%) of inadvertent hypothermia, a figure which is within the wide range of incidence variation reported in the literature between 6% and 90%.13–17 Of the variables considered in the study, only age≥65 years, female gender and BMI≥30 were found to be associated with hypothermia.

The bivariate analysis did not find a relationship between hypothermia and the time and type of anesthesia, the surgical specialty, intraoperative temperature monitoring, the use of warm intravenous fluids and the use of forced-air warming systems; additionally, the ASA classification was excluded as a result of the logistic regression. It is important to mention that some of those factors are considered in the recommendations for the prevention of inadvertent hypothermia.23

It is known that body temperature is not homogenous and that central temperature is the best indicator for thermal status in humans. Temperature determination in the pulmonary artery is the gold standard, but it has the disadvantage of being invasive. Intraoperatively, acceptable semi-invasive monitoring sites are the nasopharinx, the esophagus and the urinary bladder.19 In the systematic review of the literature, non-invasive oral measurement is valid and safe for central temperature determination,19 which would make it the best alternative in the conscious patient. Langham et al.24 found that electronic oral temperature measurement was the most adequate for use in the postoperative period, followed by axillary temperature. Höcker et al.25 showed that sublingual temperature measurement is a good practical method for monitoring perioperative temperature in both anesthetized and conscious patients.

In this study, an infrared skin thermometer was used to measure forehead temperature, because it was the device available to us. It is known that temperature in peripheral tissues depends on exposure, central temperature and vasomotor thermoregulation.12 Axillary and skin temperature is prone to artifacts,26 which is why it might not be the best option. Unlike what some authors suggest, the measurement was not adjusted with the central temperature27–29 (skin temperature 0.7°C lower than central temperature) because the equipment had been calibrated for first use with a central temperature measurement in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendation, and this calibration is stable for periods of one to three years.

Age over 60 years, female gender and high-level spinal block have been reported as risk factors for perioperative hypothermia, on the basis of weak evidence (level B, Class IIa or IIb). Risk factors with insufficient evidence (level C, Class IIa or IIb) include BMI under the normal value, normal BMI, length of the procedure, uncovered surgical area, duration of anesthesia and diabetes mellitus.30 Among the factors associated with hypothermia found in this study, the variable of a BMI≥30 did not correlate with the published data. It has been reported that greater body weight protects against central hypothermia.31,32 Fat in obese individuals has conductivity, which reduces heat loss through the skin and minimizes hypothermia.32 Moreover, the vasoconstriction threshold at low ambient temperature is high in obese patients.33 In view of the above, the result found in this study might be related to the measurement method, given that the reduced loss of heat through the skin would be particularly intensified in obese patients.

On the other hand, NICE23 has defined high-risk patients as those with two or more of the following factors: ASA greater than I, preoperative temperature below 36°C, combined anesthesia, intermediate or major surgery, and patients with cardiovascular history. They recommend measuring temperature 1h before induction, every 30min intraoperatively, and postoperatively upon arrival at the recovery room every 15min until it reaches 36°C, and then every hour until it reaches 36.5°C.

In this study, no patient was pre-warmed. Pre-warming is a current recommendation,15,23,34,35 and it attenuates substantially the initial drop in temperature in the anesthetized patient, as it prevents redistribution heat losses. Until this technique is implemented, active intraoperative warming will continue to be the primary strategy to fight hypothermia. We may state that the absence of pre-warming and the low percentage of use of intraoperative temperature monitoring may explain the lack of a statistically significant difference between hypothermic and normothermic patients despite the use of warm intravascular fluids and of a forced-air warming system. When no pre-warming is used, intraoperative warming techniques, including the use of forced-air warming, fail to eliminate the initial drop in temperature.34

Inadvertent hypothermia must be prevented. It is easier to maintain intraoperative normothermia than to rewarm patients in the postoperative period.36 Intraoperatively, the patient is vasodilated and thermal transfer is easier than when the patient is in vasoconstriction, as is the case in the postoperative period. Peripheral vasoconstriction limits the flow of heat toward the peripheral compartment, increasing the gradient due to the accumulation of heat generated by tissue metabolism in the central compartment.37

The two most important mechanisms responsible for heat loss in the operating room are radiation and convection, in that order. Radiation accounts for 60% of the losses, which is the reason why a relative humidity of >45% and a temperature ranging between 21 and 14°C must be maintained in the operating room for adult patients, and between 24 and 26°C for pediatric patients. Regarding this issue, the NICE guidelines state: “temperature in the operating room must be at least 21°C while the patient is exposed”. ASPAN recommends maintaining operating room temperature between 20 and 25°C (Class I, Level C). Operating room temperature and humidity were not recorded in this study, and that may be an important factor in the occurrence of hypothermia associated with the type of surgery.29

Forced-air warming, available since 1980, works on the principle of hot air infusion that escapes through small orifices pointing at the patient. It has been shown to be the only efficient method for maintaining temperature and warming the patients in the perioperative period.38–40 The efficacy of the system is enhanced by covering the blanket with a cotton sheet, and it has the advantage of being flexible, enabling optimal coverage of the skin surface, regardless of positioning. Reported complications with the Bair Hugger systems are rare, with one report of a third degree burn41 and one case of thermal softening of the tracheal tube.42

It has been found that the administration of warm fluids and line warming are equally effective for preventing perioperative hypothermia.43 Fluid warming does not warm the patient, but rather minimizes the incidence of perioperative hypothermia.44 In machines that allow line warming, fluids are warmed to 38°C, but they have to be warmed to 41°C when cabinets are used; in both cases, when they reach the patient their temperature is 37°C. In this study, no patient received line-warmed fluids even though the resource was available. The ATLS (Advanced Trauma Life Support) manual of the American College of Surgeons recommends microwave warming of resuscitation fluids to 39°C. The 500ml bags may be warmed at 400W for 100s or 800W for 50s. Consequently, an inexpensive alternative is to warm the fluids with microwaves.45

The systematic implementation of perioperative temperature management is amply justified. The evidence supports starting active warming before the operation and temperature monitoring throughout the perioperative period in order to prevent hypothermia. The use of warming methods is supported by the evidence, but it is optimized only when temperature is monitored, considering that it is impossible to manage temperature if it is not measured.46

In conclusion, warming measures without temperature monitoring fail to reduce the presence of hypothermia, contrary to what may be expected. Given the high incidence of inadvertent hypothermia despite the availability of adequate resources for monitoring and managing temperature, there is a need to standardize and implement action guidelines to prevent and manage its occurrence including, among other measures, pre-warming and temperature monitoring before, during and after anesthesia for all patients, in particular in the groups at risk which, in this study, were patients≥65 years and of the female gender.

FundingAuthor's own resources

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Castillo Monzón CG, et al. Manejo de la temperatura en el perioperatorio y frecuencia de hipotermia inadvertida en un hospital general. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2013;41:97–103.