Grade III anaplastic ganglioglioma is an aggressive, rare, and radiosensitive central nervous system (CNS) tumour. It is more common in males, with a ratio of 1.3 to 1. Its peak incidence is in the third decade of life. Only 10 cases were recorded in children in Colombia from 2000 to 2014, with a fatal outcome in spite of radiation therapy. This is a case of an adolescent, who began having headaches, with warning signs related to an arteriovenous malformation hindering the diagnosis of this rare tumour. This presented in its aggressive, multi-focus form. Knowledge of clinical manifestations of space-occupying intracranial lesions facilitates the assessment and treatment of affected children.

El ganglioglioma anaplásico grado III es un tumor del sistema nervioso central (SNC) agresivo, infrecuente y radiosensible. Afecta más a hombres en una relación 1,3 a 1. Su pico de incidencia se encuentra en la tercera década de la vida. Existen solo 10 casos registrados en niños en Colombia desde el 2000 al 2014, con desenlace fatal a pesar de la radioterapia. Se presenta un caso de un adolescente que debutó con cefalea con signos de alarma asociado a una malformación arteriovenosa que dificultó el diagnóstico de este raro tumor, cuya presentación fue la más agresiva: la forma multicéntrica. El conocer las manifestaciones clínicas de lesiones intracraneales ocupantes de espacio facilita la evaluación y tratamiento a los niños afectados.

The incidence of CNS tumors is variable,1 and estimated to be 35 cases per million in children under the age of 15. They are the second group of pediatric malignant tumors, making up 20-25% of all tumors;1,2 60-70% are of glial origin, and in most of them there is no metastasis.2 Usually, the supratentorial tumors are seen more in children younger than two years, and in late adolescence.2 There is an association with neurofibromatosis type I, tuberous sclerosis, and Von Hippel-Lindau, Li-Fraumeni, Turcot, Cowden, retinoblastoma (Rb), rhabdoid tumor and Gorlin syndromes,2 as well as with exposure to ionizing radiation, immunosuppression, and infection.2 Gangliogliomas (GGs) make up 0.4% of all intracranial tumors in children,1–3 they are rare, and they belong to the group of neuronal and mixed neuronal-glial tumors.3 They predominantly affect males, in a ratio of 1.3 to 1.4 In Colombia, the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología [National Cancer Institute] (INC) recorded 10 cases between 2000 and 2014 in children under the age of 18.5

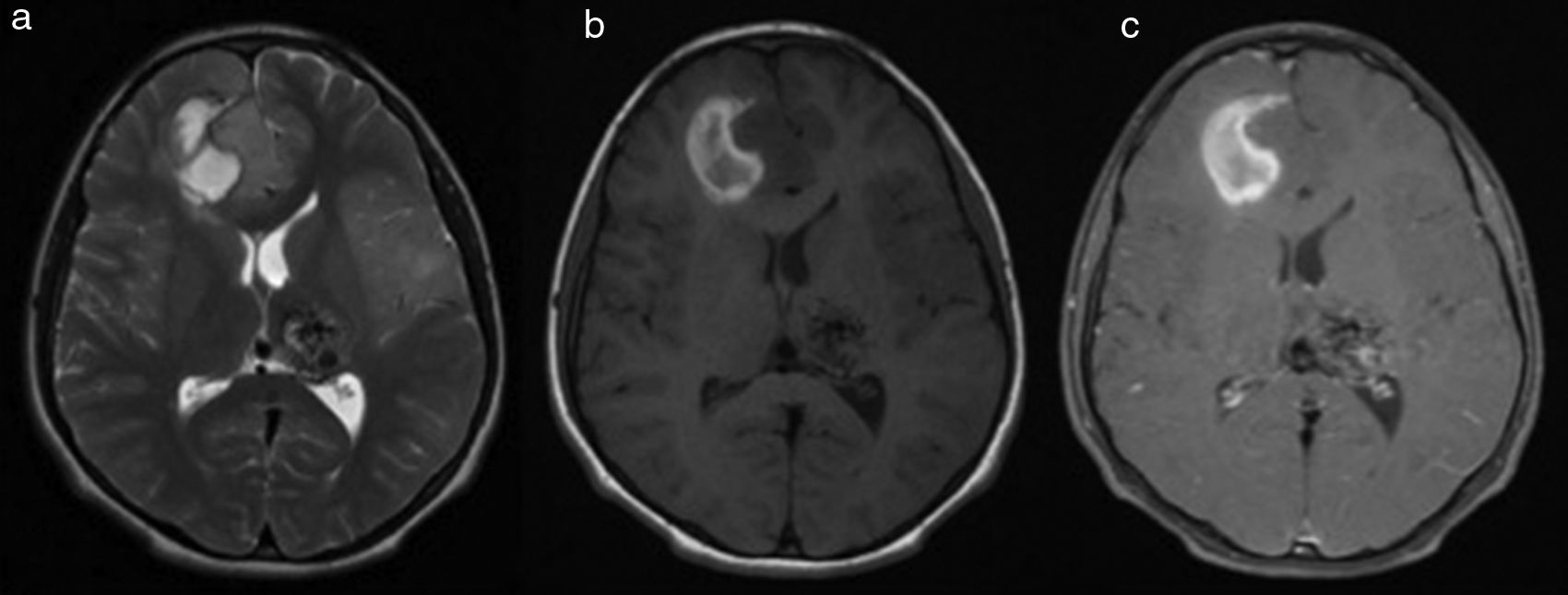

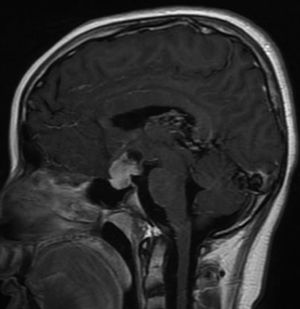

Clinical caseA 14 year old adolescent male with normal neurodevelopment, who in 2009 began to present oppressive bilateral occipital headaches: intensity 7/10, self-limited, and with impaired visual acuity. He consulted in 2014 due to a bilateral global, throbbing headache with a 10/10 intensity. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed a left thalamic arteriovenous malformation (AVM) with multiple flow voids forming a nest, associated with a vascular drainage structure, without signs of rupture or mass effect. He was referred to Hospital Militar Central (HMC) where angiography showed a Spetzler-Martin grade III AVM, and expectant management was chosen (figure 1).

In 2015, he presented anticipatory emesis with food, as well as hematemesis and progressive oppressive right parietal headache with a 10/10 intensity, projectile vomiting, dysarthria, drowsiness, weakness, paresthesias, and left leg monoparesia associated with intracerebral hemorrhage seen on computerized axial tomography (CT); he received phenytoin and was referred to HMC. On admission, he was normotensive, Tanner 2, without apparent growth alterations. A brain MRI showed an acute right frontal basal hemorrhage, perilesional edema, midline shift, and left posterior temporal cortical lesions which followed vascular territory, without an ischemic appearance (figure 2). His angiographic diagnosis was, therefore, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), with a possible tumor lesion.

Brain MRI axial cuts: a. T2, b. T1 and c. T1+MC. Right frontal parasagittal cortical-subcortical intra-axial mass of intermediate signal intensity, with a blood component, not highlighted by the contrast media. Positive signs of compression with marked adjacent vasogenic edema, and a subfalcine hernia to the left. Shows a lesion in the left thalamic region with multiple flow voids forming a nest, associated with a vascular drainage structure related to an AVM, without signs of rupture or mass effect.

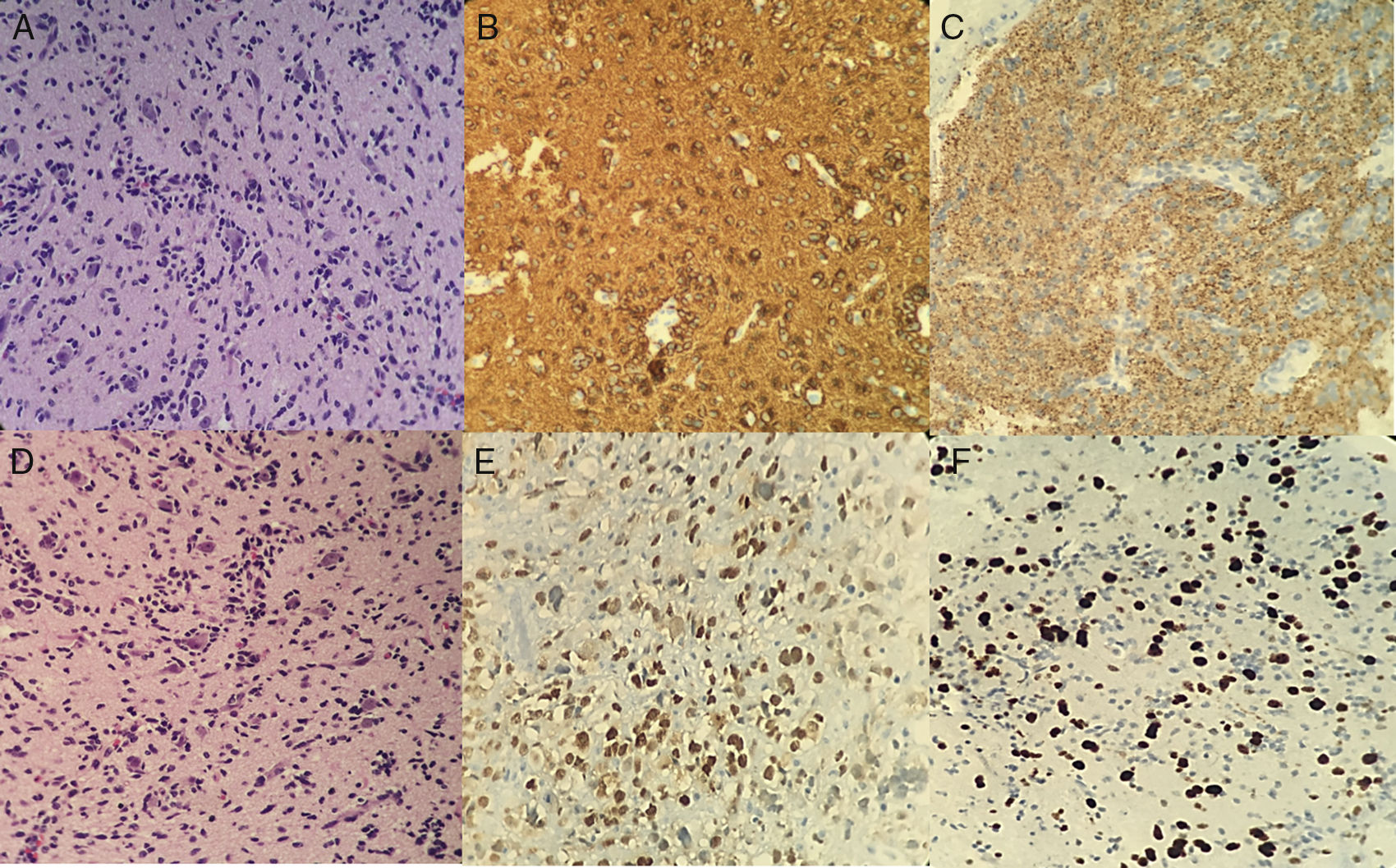

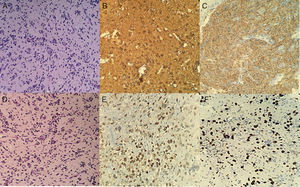

Pediatric neurology ruled out mitochondrial, autoimmune and infectious disease, and considered it to be a CVA-like disease. At 24hours, pediatric hematology-oncology found bilateral ptosis, and blood dyscrasias were ruled out. He began to experience photophobia, dizziness, left-sided facial paresthesias, and a self-limited bifrontal headache. He was discharged, and an outpatient brain MRI documented an active brain bleed with worsening of the throbbing headache, vomiting, arterial hypertension, desaturation, obtundation, and two episodes of self-limited tonic-clonic seizures, confined to the left side of the body, with ipsilateral head and gaze deviation. The head CT showed de novo diffuse bilateral temporal and frontal hypodensity of the white matter, diminished breadth of the cisterns, white matter edema, midline shift to the left and obliteration of the frontal horn of the ipsilateral ventricle with thickening of the vein of Galen and the straight sinus, due to left thalamic malformation. Due to hematemesis, a syncopal episode, right hemiparesia, peribuccal cyanosis, upward gaze deviation with progression to total paresia, and generalized hypertonia, he was readmitted to HMC. The head CT showed a right frontal hypodense lesion without mass effect or signs of intracranial hypertension (IH). An interdisciplinary medical team concluded that a biopsy was needed, it showed hard, violet brain tissue, confirming a malignant CNS neoplasm with small, anaplastic tumor cells. Immunohistochemistry revealed grade III ganglioglioma, with poor expression of the P53 oncogene, and a 12% Ki67 cell proliferation index (figure 3).

A and B. Neoplasia with compact growth and extension to the subarachnoid space. Two components can be seen: the neuronal component with dysmorphic neurons, pleomorphic nuclei (some with a prominent nucleolus), and loss of the Nissl bodies; and the mixed glial component with neoplastic astrocytes and some mitoses. C. Reactive glial fibrillary acidic protein. D. Focally reactive p53. E. Ganglion cells with fine granular markings. F. Ki67 15% lower in the neuronal component.

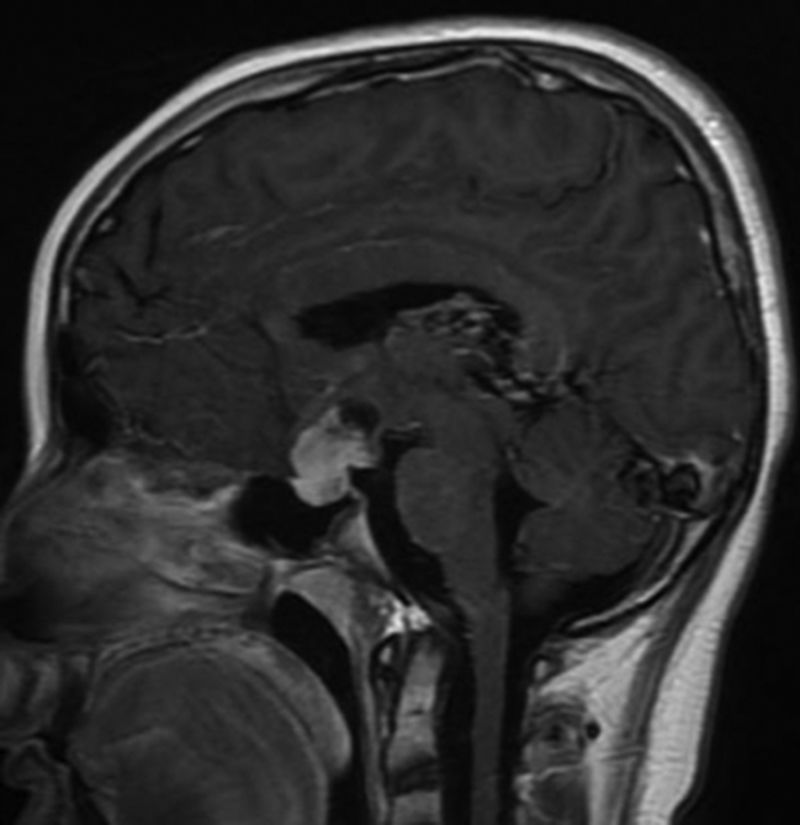

Due to grade III GG with a poor prognosis, radiation therapy and temozolomide were begun without a surgical option. Tumor effects on the eyes were ruled out. He was discharged for outpatient systemic polychemotherapy, but worsening headaches, vomiting, weakness, confusion, bradylalia and incoherent phrases led to his readmission a month later. An extrainstitutional opinion requested by the parents was reported as: ̈Grade III anaplastic ganglioma, according to the WHO classification̈. He was assessed using the WISC IV + pediatric Weschler intelligence quotient test, with a score of 58, related to the cognitive deficit secondary to frontal involvement. He began antineoplastic treatment with torpid progress and intermittent memory loss, leading to readmission to HMC. He had macroscopic hematuria, for which etiologies other than nephrotoxicity secondary to the antineoplastic treatment were ruled out. His condition worsened, with dyslalia, lateral pulsion, widened stance, decreased left-sided strength, and progressive back pain with painful thoracic and lumbar paravertebral points. Spinal column metastases were ruled out by MRI. He presented euvolemic hyponatremia with elevated natriuresis, and progressed from hyponatremia to hypernatremia secondary to neuroendocrine impairment, with supra- and sellar metastastic involvement of the hypophisis (figure 4). There was no pubertal or neurodevelopmental change on physical exam.

He progressed to somnolence, left divergent strabismus, dysarthria, hemiparesia, inability to walk, and respiratory failure, and was transferred to the PICU. He presented fever, leukopenia and lymphopenia, with no microorganisms isolated in blood. He required hemodynamic and respiratory support for three weeks, after which he was able to change from an invasive ventilatory system to a non-invasive system, and was transferred to the pediatric neurology floor, where he died 14 months after the tumor diagnosis.

DiscussionUnexplained headaches in pediatrics are a warning sign, especially when they are associated with a progressive increase in frequency or intensity, increased intensity with Valsalva maneuvers, projectile vomiting, altered consciousness, dysarthria, diplopia, weakness, ataxia, dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, strabismus, papilledema, focalization, and IH. In these cases, space occupying lesions must be ruled out through neuroimaging, with tumors being the main differential diagnosis.6–10 This was seen in this case study patient, who began with progressive, oppressive bilateral occipital headaches, altered visual acuity, projectile vomiting, dysarthria, somnolence, weakness, convulsions and paresthesias related to the AVM. However, neuroimaging should be rationalized in children with headaches, as it is reported to be frequently used in patients with migraines, chronic headaches or headaches without red flags.11 The head MRI findings reported a greater impact on one lobe. In general, solids prefer the temporal lobe (>70%), as in this case study, although they have been described in the frontal, parietal, cerebellar, hypophyseal, pineal gland, brain stem, spinal cord and intraventricular regions.2,12–24 There have been reports of cystic, hemorrhagic and solid components which make tumor resection difficult because of edema, signs of IH and neuroendocrine involvement, which were observed in the reported case due to the presence of hypophyseal lesions. No cases of GG with angiographically documented AVM in children were found in the literature review. This was an interesting finding, since the AVM bleed masked the presentation and clinical diagnosis of the case study, due to its behavior as a space-occupying lesion.

Ganglioglioma has a rapid-growth neuronal, ganglionic, and glial clonal ontogenesis, described by Koelsche et al.,25 with a V600E point mutation in the BRAF 1 gene, non-specific for GG, but whose presence is associated with a lower recurrence-free survival. This mutation stimulates the cascade of the MAPK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases) kinase-dependent protein family, which stimulates the mitosis, differentiation, and resistance to apoptosis of cell groups which then become neoplasms by duplication of 7q34, with fusion of KIAA1549-BRAF,26 having a poor survival prognosis. This was not studied in our patient since the necessary tissue was not available, as it was used for the extrainstitutional opinion. Another histopathological characteristic is increased vascular endothelial proliferation manifested by intracranial bleeds, which were described in this case study. These have a poor prognosis, with loss of CD34, p53 mutation, expression of the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), synaptophysin, neurofilament, neuron specific enolase, CD56, variably expressed chromogranin, and Ki67 > 5%, as in the described case, with Ki67 >12%.2–3

With regard to treatment, there is no chemotherapeutic protocol, but the preliminary report of a phase three study stated that there was no difference in survival in the combination of temozolamide and radiation therapy plus bevacizumab.23 However, in the case being reported, a 14 month survival was achieved with a combination of temozolamide and radiation therapy, similar to that reported by Zanello M et al. between 2000 and 2015.27

The prognostic factor which improves survival is unifocal disease, which does not apply in this case, since multifocal disease was documented.4,23–29 Multifocal disease has a high recurrence rate compared with low-grade GGs;30,31 it is difficult to control due to its multifocal extension, which makes complete surgical resection difficult.30–34 Also, the impairment of p53 with elevated Ki67 is associated with an aggressive biological behavior, with a less favorable prognosis. There is no apparent benefit from adjunct radiation therapy, because it does not improve the survival rate, and may cause CN II and VIII neuropathy, involvement of the lens and retina, neuroendocrine impairment and the appearance of new neoplasms.2,28,29 Unexplained headaches in pediatrics are a warning sign. If they are associated with an increase in the frequency or intensity of the headaches, an increased intensity with Valsalva maneuvers, projectile vomiting, altered consciousness, dysarthria, diplopia, weakness, ataxia, dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, strabismus, papilledema, focalization and IH (arterial hypertension, bradycardia, and altered breathing patterns), space-occupying lesions must be ruled out by neuroimaging, with tumors being the main differential diagnosis. Gangliogliomas, which are tumors, have very poor survival rates, which may be associated with intracranial bleeding and refractory epilepsy, and topographical neurologic impairment.

Funding sourcesThis work was carried out in the Pediatric Neurology Department of the Central Military Hospital.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interests.

Dr. Javier Muñoz Narváez, Pediatric Oncologist, Clínica del Country, for his review and opinion of the report. To Dr. Rodrigo Castro Rebolledo, Physiatrist, for his help in drafting and bibliographic searching.