Suicidal ideation refers to thoughts that range from a vague idea of committing suicide to a specific suicide plan.

ObjectiveTo explore factors such as demographic, social, family, abuse, risk of depression, habits and health conditions, which influence suicidal ideation in the elderly people in the cities of Medellín, Barranquilla, and Pasto (Colombia), with the intention to identify those associated factors that can be used in public health programmes focused on this population.

MethodsCross-sectional analytical study was conducted using a secondary source, demographic, social, clinical variables, social support, discrimination, abuse, happiness, depression, functional capacity, and as a dependent variable were asked the question: “Have you ever thought about committing suicide?” A descriptive, bivariate and multivariate analysis was performed.

ResultsThe median age was ≤69 [interquartile range, 11] years, and 58.2% were women. The prevalence of suicidal ideation was 6.4%, and of these, 28.7% had made plans to end their lives, and 66.7% had tried at least once. A statistical association was found with informal employment, cigarette consumption, alcohol and psychoactive substances, risk of depression, having a disability, dissatisfaction with their quality of life, with their health, with their economic situation, as well as feeling unhappy, bad treatment and bad relationships among family members, poor social support, sexual and economic abuse, and finally, discrimination.

ConclusionsSuicidal ideation in older adults in three cities of Colombia is explained by the sexual and economic abuse that this population is suffering, as well as bad personal relationships between the members of the family of the older adult. The risk of depression increases the probability of having thoughts against one’s life.

La ideación suicida se refiere a pensamientos que abarcan desde una vaga idea de suicidarse a un plan específico de suicidio.

ObjetivoExplorar factores demográficos, sociales y familiares, maltrato, riesgo de depresión y hábitos y condiciones de salud que influyen en la ideación suicida del adulto mayor en las ciudades de Medellín, Barranquilla y Pasto, para identificar aquellos en los que se puede intervenir con programas de salud pública enfocados en esta población.

MétodosEstudio analítico transversal con fuente secundaria; se consideraron variables demográficas, sociales y clínicas, apoyo social, discriminación, maltrato, felicidad, depresión y capacidad funcional, y como variable dependiente, la pregunta: «¿ha pensado en atentar contra su vida?». Se realizaron análisis descriptivo, bivariable y multivariable.

ResultadosLa mediana de edad fue ≤69 (intervalo intercuartílico, 11) años; el 58,2% eran mujeres; la prevalencia de ideación suicida fue del 6,4%; el 28,7% de estos había hecho planes para terminar con su vida y el 66,7% lo había intentado al menos una vez. Se encontró asociación estadística con el empleo informal, el consumo de cigarrillos, alcohol y sustancias psicoactivas, el riesgo de depresión, tener discapacidad, la insatisfacción con la calidad de vida, la salud y la situación económica, sentirse infeliz, los maltratos y las malas relaciones entre los miembros de la familia, el escaso apoyo social, el maltrato sexual y económico y, por último, la discriminación.

ConclusionesLa ideación suicida de los adultos mayores en 3 ciudades de Colombia se explica por el maltrato sexual y económico que sufre esta población; asimismo las malas relaciones personales entre los miembros de la familia del adulto mayor y el riesgo de depresión aumentan la probabilidad de que se presenten pensamientos contra la propia vida.

Suicidal ideation is a premeditated desire to end one's own life, with either non-specific or detailed plans for the actions to take.1,2 Suicide, the fatal outcome of suicidal ideation, results in around one million deaths per year.3 As a result, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) have heightened their efforts to address this problem and recommend increased research on suicidal behaviour in general.4

Suicidal ideation is one component of suicide, along with planning, preparation, intent, execution of intent and suicide itself. All these elements are considered risk factors. The more they interact in an individual, the higher that individual's risk of suicide, since these steps do not occur sequentially, nor are all of them required for one to end one's own life.5

Many people experience suicidal thoughts, and around one-third of people who have had a non-fatal suicide attempt try to commit suicide again within a year.2 It is estimated that each suicide may have been preceded by 20–25 attempts.6 For older adults, this figure drops to four attempts3; therefore, it is important to stress that suicide attempts are far less common than suicidal ideas7 and that close to 10% of those who attempt suicide ultimately do die by suicide.2

Most studies on the subject have been conducted in adolescents. There is little information on suicidal ideation in older people, who comprise the age group with the most cases of suicide8,9 as they use lethal methods9 and show fewer warning signs that are more difficult to detect.1 This means that suicidal ideation in an older adult is more likely to lead to completed suicide.10

People 60 years of age and older comprise the age group with the highest rates of suicide.11,12 The main associated factors are as follows:

- •

Poor health in general,11 mental illnesses,12,13 regular hospitalisations and treatments received,8 disability or loss of function,12–14 and number and duration of physical diseases.1,15,16

- •

Psychiatric causes such as depression of any aetiology, chronic sleep disorders, paranoid delusional psychoses featuring deep distrust and agitation, and mental confusion.8

- •

Psychological factors accompanied by different emotions17 such as rejection, loss, loneliness, depression, hopelessness, low self-esteem,10,15,16 feeling of uselessness, inactivity, boredom and lack of life plans, with a tendency to relive the past and suffering caused by an overwhelming event.8,18

- •

Family factors such as loss of loved ones,19 forced migration, admission to a senior care centre8 and lack of a partner10,15,16 (these are the causes most commonly associated with suicidal behaviour20).

- •

Social, environmental and demographic factors such as retirement, social isolation, society's contemptuous attitude towards the elderly and loss of prestige, frequency of participation in social activities,10,15,16 age, sex, economic situation, and various social considerations in older adults.13,21

- •

Prior suicidal behaviours19 characterised by having ideals of self-destruction, suicide planning, a prior suicide attempt, availability of means to die by suicide and family history.20

Among demographic factors, it was found that women have more suicidal ideation,3,12,22 but that the risk of death by suicide is greater for men in a 4:1 ratio23; according to the distribution of cases by rate, those at highest risk of suicide in Colombia are men over 75 years of age.24 Another risk factor is age; according to PAHO, those over 70 years of age are more likely to die by suicide, primarily in the Americas.13 In addition, the highest percentage of suicidal ideation is seen in those with a low income versus those in a better economic situation,10,22 and unemployment showed a positive association with suicidal ideation.25

In older adults, suffering from chronic diseases, loss of function and disability, as well as losing a loved one, have been identified as causes of suicidal ideation.13 Drug abuse and dependency, alcohol use, and tobacco use are significant risk factors for suicidal ideation.12,26 One study reported that 67.4% of older adults who had suicidal thoughts presented cardiac risk factors.10

Risk factors for suicidal behaviour include altered psychological states,18 mental illnesses, personality disorders, schizophrenia13 and gambling disorders,14 psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, depressive disorder, and hopelessness.12 Close to 95% of suicides occur in patients with mental illnesses, and around 15% occur in patients with depression.23 The diagnosis believed to be most common in individuals with suicidal ideation is major depression in older adults.15,27,28 Major depressive disorder and other mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder, may increase suicide risk by up to 20 times.29

There is a link between suicidal ideation and marital status.23 Zhang et al.15 found that 82.5% of widowed and divorced individuals had suicidal ideation,15 and Handley et al.10 found that 68.8% were married.10 Social factors such as interpersonal ties and support should be taken into account in attempts to explain suicide.16

In Colombia, no studies on suicidal ideation in older adults were found; however, the Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental [Colombian National Mental Health Survey] has reported a prevalence of suicidal ideation in people over 45 years of age of 6.5% (confidence interval: 5.3%–7.8%) and that the suicide rate in men is higher among those over 60 years of age.30 Macana Tuta reported an increase in the suicide rate in the population over 80 years of age, from 5.73 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2010 to 6.04 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2011.31 Forensis reported a 9.0% increase in suicide among older adults.24

The social coexistence and mental health dimension of Colombia's Plan Decenal de Salud Pública [Ten-Year Public Health Plan (PDSP)] for 2012–2021 proposes actions and goals for reducing rates of suicide in the country, and its cross-cutting dimension on differential management of vulnerable populations includes older adults as a special group.32 According to the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [Colombian National Administrative Department for Statistics (DANE)], in 2017, 2097 deaths due to intentionally self-inflicted wounds were recorded33; in addition, the Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social [Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection] reported that 1833 people die by suicide each year.34

The lack of information on suicidal ideation in Colombia is notable, considering that said ideation is a component of suicidal behaviour considered a risk factor for suicide,5 and that no prior information was found on suicidal ideation in older adults in the country.

Around the world, there is little evidence on suicidal ideation in older adults; the existing evidence points to high prevalences in New Zealand (15.7%), England (14.8%) and Japan (10.9%) and low prevalences in Italy (3%).12 In South America, the highest figures correspond to Chile. Silva et al.12 found that the prevalence of thinking a great deal about death was 35.5%, that of wishing to be dead was 20%, that of suicidal ideation was 14.3% and that of at least one suicide attempt was 7.7%.

The objective of this study is to examine demographic, social and family factors; abuse; risk of depression; toxic habits; and health conditions that influence suicidal ideation in older adults in the cities of Medellín, Barranquilla and Pasto, in order to identify opportunities for intervention with public health programmes aimed at this population.

MethodsA cross-sectional analytical study, with secondary information based on the study "Índice de vulnerabilidad del adulto mayor, en tres ciudades de Colombia, 2016" [Index of vulnerability in older adults in three cities in Colombia, 2016].35 For this study 1514 adults aged 60 or older residing in the urban areas of Medellín, Barranquilla and Pasto were surveyed; 51 surveys of older adults with cognitive decline were excluded, for a final total of 1463 surveys. The macro study performed probability sampling in clusters by district (for Medellín and Barranquilla) or municipality (for Pasto), and each underwent two-stage sampling. The first stage consisted of randomised systematic sampling of neighbourhoods within each district, and the second stage consisted of randomised selection of blocks within each neighbourhood. In each block, all resident older people were surveyed in their dwellings, as a final unit of analysis. The survey was administered by professionals with standardised training.

This sampling was used to calculate selection probabilities in each sampling stage. The first sampling stage corresponded to selecting neighbourhoods; the probability of neighbourhood selection (PNS) was estimated based on:

The second sampling stage corresponded to selecting blocks; the probability of block selection (PBS) was estimated based on:

As Pasto lacked information on blocks by neighbourhood, PNS was not calculated and PBS was calculated based on:

Of the blocks selected, all dwellings were taken and all the older adults in each dwelling were surveyed; the probability of dwelling selection (PDS) and the probability of older adult selection (POAS) were = 1.0. Based on the calculation of these probabilities, the end probability (EP) of older adult selection was estimated:

In order to infer the results in the population, the basic expansion factor (BEF) was calculated; this corresponded to the inverse of the EP, which indicated how many older adults each survey respondent represented:

To correct for bias and get the sample to resemble the projected population as closely as possible, correction factors were used according to each city's population characteristics:

- •

Proportion of non-response.

- •

Male-to-female ratio of the population group.

- •

Male-to-female ratio of survey respondents.

- •

Older-adults-to-dwelling ratio.

- •

Proportion of people in the urban area.

This was used to determine the final expansion factor (FEF):

The sample of 1514 older adults had a rate of good general health of 80.3%, and a sampling error of 3.3%. The population of older adults residing in the urban area of the three cities is 579,647; the sample was expanded to 557,285 and with this the demographic analysis of the population was performed.

The measurement instrument included demographic variables (age, sex, level of education, occupation, marital status, social class and income), social variables (use of legal and illegal psychoactive substances, leisure activities, quality of life, interactions and relationships among family members, and community organisations in which the survey respondent was involved) and clinical variables (disease and disability). Scales were also used to measure: social support (Medical Outcomes Study [MOS] scale36), discrimination (Everyday Discrimination Scale37), abuse (Geriatric Abuse scale38), happiness (Lima Happiness Scale39), depression (Yesavage's Abridged Geriatric Depression scale40) and functional capacity (Barthel Index41). The dependent variable was suicidal ideation, which was investigated with the question: "Have you thought about attempting to take your own life?"

The database was used with the authorisation of Universidad CES. The information was processed and analysed with the statistics software package SPSS®, version 21 (IBM Corp.; Armonk, New York, United States), licence protected by the same university.

The study population was described using measures of central tendency, dispersion or position, depending on the distribution of the data determined using a normality test; for qualitative variables, measures of absolute and relative frequency were used. The bivariate analysis explored the association between suicidal ideation and the independent variables of interest using the χ2 test of independence and the prevalence ratio (PR) with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), and odds ratios (ORs) were calculated to adjust for confounding variables and used to estimate PRs, considering that the prevalence of suicidal ideation in this population was low (<10%).42 Finally, logistic regression was performed in order to determine the factors that accounted for suicidal ideation; for this, variables with a p-value <0.05 were incorporated into the model. In addition, a collinearity analysis was performed and the variables were recategorised.43

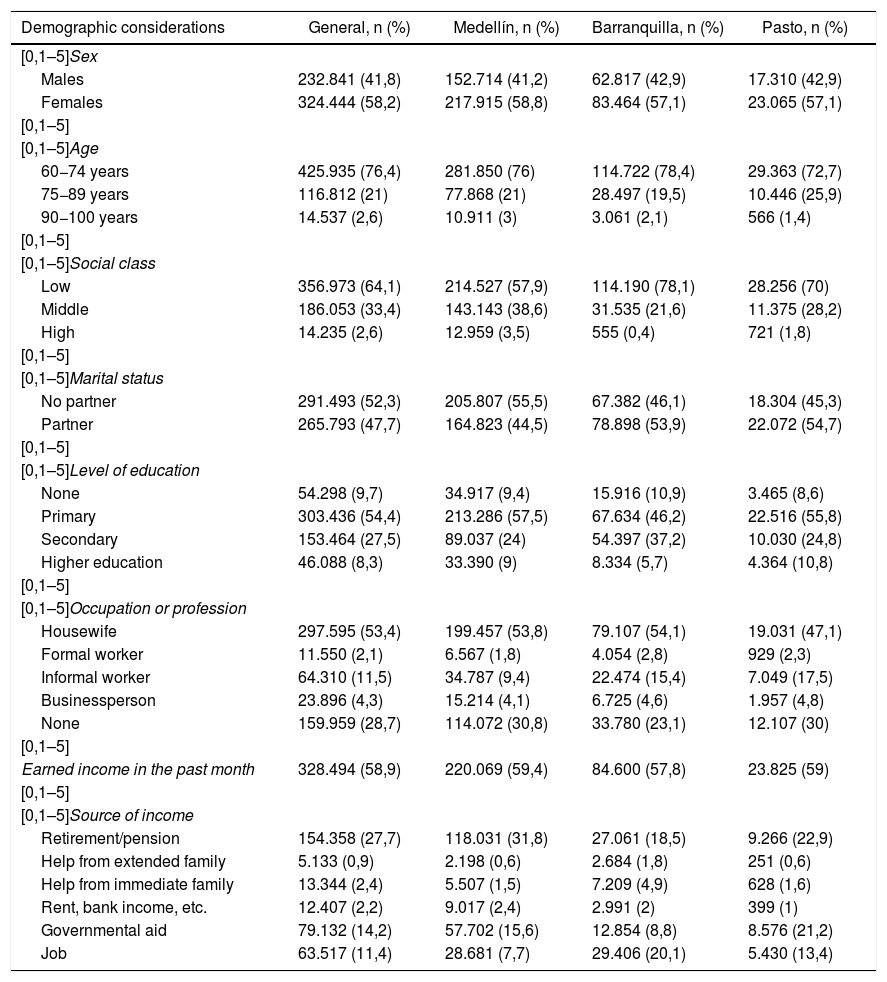

ResultsDemographic characteristics of older adultsOf the older adults surveyed, 50% were ≤69 (interquartile range: 11; range: 60–100) years of age. Women comprised 58.2% of the population; Barranquilla residents had the highest percentage of adults belonging to a low social class (78.1%) and 3.5% of Medellín residents belonged to a high social class; 47.7% indicated that they had a partner. In Barranquilla, 10.9% of older adults lacked an education; in Pasto, this figure was similar, but the rate of higher education (10.8%) differed. Concerning occupations, it was found that just 2.1% had a formal job; 11.5% had an informal job (the highest rate being in Pasto, at 17.5%); and 27.7% indicated that they were retired, with residents of Medellín reporting the highest retirement rate (31.8%) and residents of Barranquilla reporting the lowest (18.5%). The distribution of demographic characteristics by city is presented in Table 1.

Proportional distribution of older adults by demographic characteristics in 3 cities in Colombia, 2016.

| Demographic considerations | General, n (%) | Medellín, n (%) | Barranquilla, n (%) | Pasto, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–5]Sex | ||||

| Males | 232.841 (41,8) | 152.714 (41,2) | 62.817 (42,9) | 17.310 (42,9) |

| Females | 324.444 (58,2) | 217.915 (58,8) | 83.464 (57,1) | 23.065 (57,1) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Age | ||||

| 60−74 years | 425.935 (76,4) | 281.850 (76) | 114.722 (78,4) | 29.363 (72,7) |

| 75−89 years | 116.812 (21) | 77.868 (21) | 28.497 (19,5) | 10.446 (25,9) |

| 90−100 years | 14.537 (2,6) | 10.911 (3) | 3.061 (2,1) | 566 (1,4) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Social class | ||||

| Low | 356.973 (64,1) | 214.527 (57,9) | 114.190 (78,1) | 28.256 (70) |

| Middle | 186.053 (33,4) | 143.143 (38,6) | 31.535 (21,6) | 11.375 (28,2) |

| High | 14.235 (2,6) | 12.959 (3,5) | 555 (0,4) | 721 (1,8) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Marital status | ||||

| No partner | 291.493 (52,3) | 205.807 (55,5) | 67.382 (46,1) | 18.304 (45,3) |

| Partner | 265.793 (47,7) | 164.823 (44,5) | 78.898 (53,9) | 22.072 (54,7) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Level of education | ||||

| None | 54.298 (9,7) | 34.917 (9,4) | 15.916 (10,9) | 3.465 (8,6) |

| Primary | 303.436 (54,4) | 213.286 (57,5) | 67.634 (46,2) | 22.516 (55,8) |

| Secondary | 153.464 (27,5) | 89.037 (24) | 54.397 (37,2) | 10.030 (24,8) |

| Higher education | 46.088 (8,3) | 33.390 (9) | 8.334 (5,7) | 4.364 (10,8) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Occupation or profession | ||||

| Housewife | 297.595 (53,4) | 199.457 (53,8) | 79.107 (54,1) | 19.031 (47,1) |

| Formal worker | 11.550 (2,1) | 6.567 (1,8) | 4.054 (2,8) | 929 (2,3) |

| Informal worker | 64.310 (11,5) | 34.787 (9,4) | 22.474 (15,4) | 7.049 (17,5) |

| Businessperson | 23.896 (4,3) | 15.214 (4,1) | 6.725 (4,6) | 1.957 (4,8) |

| None | 159.959 (28,7) | 114.072 (30,8) | 33.780 (23,1) | 12.107 (30) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| Earned income in the past month | 328.494 (58,9) | 220.069 (59,4) | 84.600 (57,8) | 23.825 (59) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Source of income | ||||

| Retirement/pension | 154.358 (27,7) | 118.031 (31,8) | 27.061 (18,5) | 9.266 (22,9) |

| Help from extended family | 5.133 (0,9) | 2.198 (0,6) | 2.684 (1,8) | 251 (0,6) |

| Help from immediate family | 13.344 (2,4) | 5.507 (1,5) | 7.209 (4,9) | 628 (1,6) |

| Rent, bank income, etc. | 12.407 (2,2) | 9.017 (2,4) | 2.991 (2) | 399 (1) |

| Governmental aid | 79.132 (14,2) | 57.702 (15,6) | 12.854 (8,8) | 8.576 (21,2) |

| Job | 63.517 (11,4) | 28.681 (7,7) | 29.406 (20,1) | 5.430 (13,4) |

According to the social factors analysed, older adults reported adequate social support (91.9%). Among the cities in the study, Barranquilla had the highest rate of social support (96.4%), a small percentage reported abuse among family members (9.8%) and poor relationships among family members (0.9%), 57.6% always had someone to help them when they had to be in bed, 55.4% always had someone to advise them when they had problems, 68.8% did not participate in any community organisations and 50% had three or fewer close friends or four or fewer close family members.

With regard to abuse, 1.5% had been threatened with being taken to a nursing home; 10.3% had been left alone; 13.8% had been discriminated against; 86.6% were not at risk of depression; 88.4% had a suitable functional capacity and 97% were enrolled in the health system. Regarding toxic habits, most did not smoke (57.6%), did not drink alcohol (61.0%) and did not use psychoactive substances (98.0%). The main leisure activities reported were listening to the radio and watching television (51.1%). Notably, in Medellín, 21.6% of older adults had been left alone. In Barranquilla, 12.7% had experienced psychological abuse, and, in Pasto, 14.9% were found to have been abused. The percentage distribution of abuse with these characteristics by city is presented in Table 2.

Percentage distribution of older adults by abuse in 3 cities in Colombia, 2016.

| Abuse | General, n (%) | Medellín, n (%) | Barranquilla, n (%) | Pasto, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Having been threatened with being taken to a nursing home | 22 (1,5) | 11 (2,4) | 8 (1,6) | 3 (0,6) |

| Having been left alone | 151 (10,3) | 100 (21,6) | 11 (2,2) | 40 (8) |

| Abuse (Yes) | 143 (9,8) | 43 (9,3) | 26 (5,2) | 74 (14,9) |

| Physical abuse (Yes) | 35 (2,4) | 19 (4,1) | 12 (2,4) | 4 (0,8) |

| Psychological abuse (Yes) | 119 (8,1) | 32 (6,9) | 64 (12,7) | 23 (4,6) |

| Neglect (Yes) | 30 (2,1) | 5 (1,1) | 19 (3,8) | 6 (1,2) |

| Economic abuse (Yes) | 19 (1,3) | 10 (2,2) | 5 (1) | 4 (0,8) |

| Sexual abuse (Yes) | 2 (0,1) | 1 (0,2) | 1 (0,2) | 0 (0) |

| Discrimination (Yes) | 202 (13,8) | 43 (9,3) | 51 (10,1) | 108 (21,7) |

As for clinical conditions in older people, the most common diseases were found to be hypertension (50.6%) and diabetes (14.9%). At least one disability was present in 48.6% of the population; visual disabilities were the most common, with an approximate prevalence of 50%. Satisfaction with their quality of life was reported by 62.0% of the population; of these, 67.4% resided in Pasto. Overall, 58.9% were satisfied with their health; notably, 65.1% of Barranquilla residents were satisfied with their health. A total of 44.6% (51.8% of whom resided in Barranquilla) reported being satisfied with their current economic situation, and 52.7% reported feeling happy.

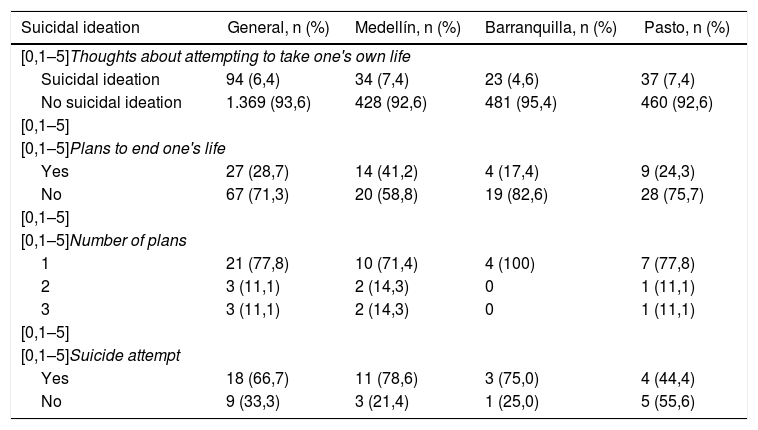

Prevalence of suicidal ideation in older adultsAltogether, 94 older adults (6.4%) indicated having had suicidal ideation at least once. Of these, 34 (7.4%) resided in Medellín, 23 (4.6%) resided in Barranquilla and 37 (7.4%) resided in Pasto. Some 28.7% indicated that they had made plans to end their own life. Among them, 77.8% stated that they had made specific plans at least once in their life and 66.7% indicated that they had attempted suicide in some way. The highest percentage of suicidal ideation was recorded in women (66%). Notably, in Medellín, 71.4% of older adults once planned a suicide attempt and, of these, 78.6% acted on that intent; in Barranquilla, all older adults with suicidal ideation planned a suicide attempt and, of them, 75.0% acted on it; and, in Pasto, 77.8% planned their death and only 44.4% attempted suicide (Table 3).

Percentage distribution of older adults according to characteristics related to suicidal ideation in 3 cities in Colombia, 2016.

| Suicidal ideation | General, n (%) | Medellín, n (%) | Barranquilla, n (%) | Pasto, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–5]Thoughts about attempting to take one's own life | ||||

| Suicidal ideation | 94 (6,4) | 34 (7,4) | 23 (4,6) | 37 (7,4) |

| No suicidal ideation | 1.369 (93,6) | 428 (92,6) | 481 (95,4) | 460 (92,6) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Plans to end one's life | ||||

| Yes | 27 (28,7) | 14 (41,2) | 4 (17,4) | 9 (24,3) |

| No | 67 (71,3) | 20 (58,8) | 19 (82,6) | 28 (75,7) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Number of plans | ||||

| 1 | 21 (77,8) | 10 (71,4) | 4 (100) | 7 (77,8) |

| 2 | 3 (11,1) | 2 (14,3) | 0 | 1 (11,1) |

| 3 | 3 (11,1) | 2 (14,3) | 0 | 1 (11,1) |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Suicide attempt | ||||

| Yes | 18 (66,7) | 11 (78,6) | 3 (75,0) | 4 (44,4) |

| No | 9 (33,3) | 3 (21,4) | 1 (25,0) | 5 (55,6) |

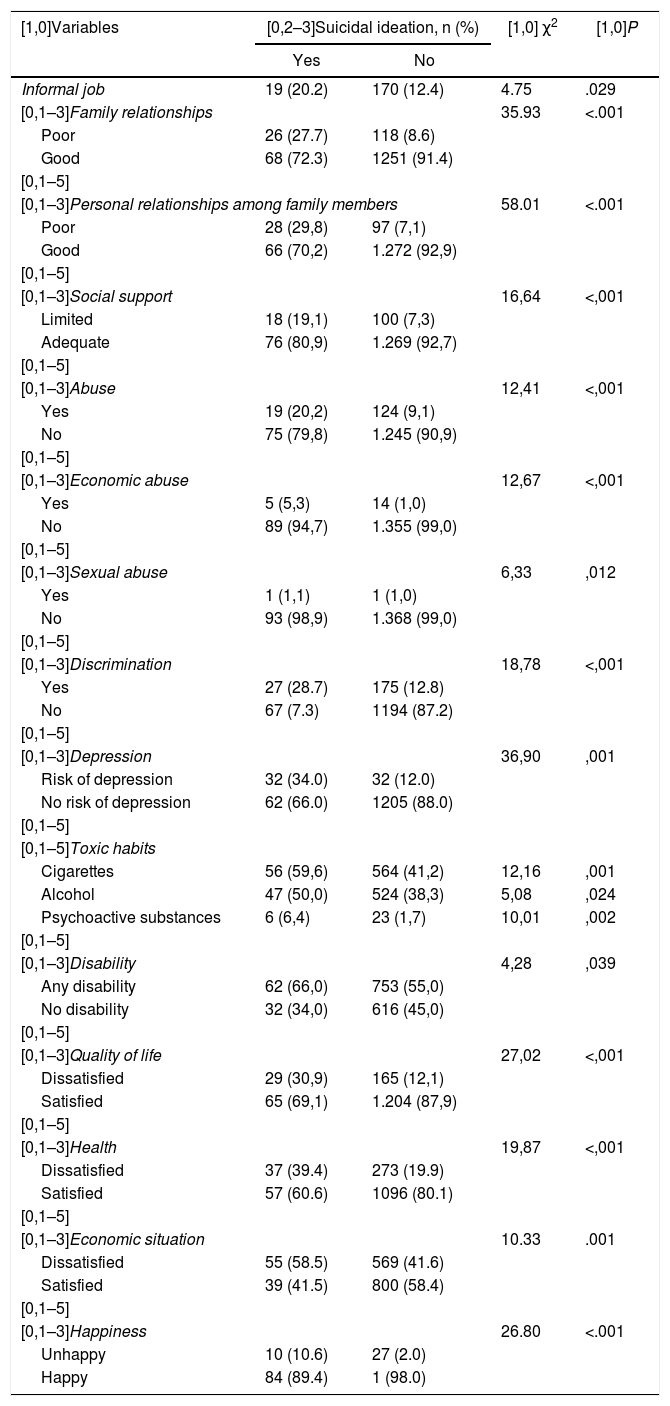

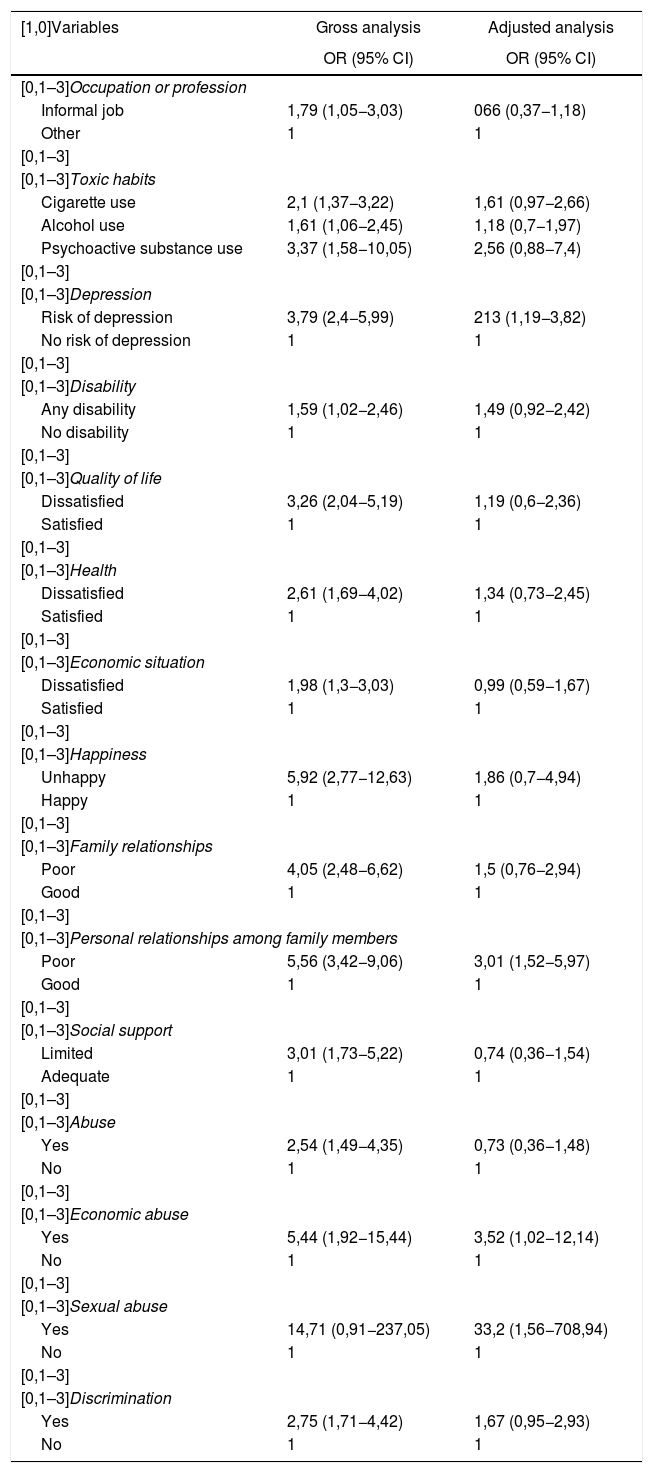

The bivariate analysis found a statistically significant association between suicidal ideation and the following characteristics: informal job, cigarette use, alcohol use, psychoactive substance use, risk of depression, having any disability, dissatisfaction with one's quality of life, dissatisfaction with one's health, dissatisfaction with one's current economic situation, feeling unhappy, abuse among family members, poor personal relationships among family members, limited social support, sexual abuse, economic abuse and feeling discriminated against (Table 4).

Factors associated with suicidal ideation in older adults in 3 cities in Colombia, 2016.

| [1,0]Variables | [0,2–3]Suicidal ideation, n (%) | [1,0] χ2 | [1,0]P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Informal job | 19 (20.2) | 170 (12.4) | 4.75 | .029 |

| [0,1–3]Family relationships | 35.93 | <.001 | ||

| Poor | 26 (27.7) | 118 (8.6) | ||

| Good | 68 (72.3) | 1251 (91.4) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Personal relationships among family members | 58.01 | <.001 | ||

| Poor | 28 (29,8) | 97 (7,1) | ||

| Good | 66 (70,2) | 1.272 (92,9) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Social support | 16,64 | <,001 | ||

| Limited | 18 (19,1) | 100 (7,3) | ||

| Adequate | 76 (80,9) | 1.269 (92,7) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Abuse | 12,41 | <,001 | ||

| Yes | 19 (20,2) | 124 (9,1) | ||

| No | 75 (79,8) | 1.245 (90,9) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Economic abuse | 12,67 | <,001 | ||

| Yes | 5 (5,3) | 14 (1,0) | ||

| No | 89 (94,7) | 1.355 (99,0) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Sexual abuse | 6,33 | ,012 | ||

| Yes | 1 (1,1) | 1 (1,0) | ||

| No | 93 (98,9) | 1.368 (99,0) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Discrimination | 18,78 | <,001 | ||

| Yes | 27 (28.7) | 175 (12.8) | ||

| No | 67 (7.3) | 1194 (87.2) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Depression | 36,90 | ,001 | ||

| Risk of depression | 32 (34.0) | 32 (12.0) | ||

| No risk of depression | 62 (66.0) | 1205 (88.0) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Toxic habits | ||||

| Cigarettes | 56 (59,6) | 564 (41,2) | 12,16 | ,001 |

| Alcohol | 47 (50,0) | 524 (38,3) | 5,08 | ,024 |

| Psychoactive substances | 6 (6,4) | 23 (1,7) | 10,01 | ,002 |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Disability | 4,28 | ,039 | ||

| Any disability | 62 (66,0) | 753 (55,0) | ||

| No disability | 32 (34,0) | 616 (45,0) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Quality of life | 27,02 | <,001 | ||

| Dissatisfied | 29 (30,9) | 165 (12,1) | ||

| Satisfied | 65 (69,1) | 1.204 (87,9) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Health | 19,87 | <,001 | ||

| Dissatisfied | 37 (39.4) | 273 (19.9) | ||

| Satisfied | 57 (60.6) | 1096 (80.1) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Economic situation | 10.33 | .001 | ||

| Dissatisfied | 55 (58.5) | 569 (41.6) | ||

| Satisfied | 39 (41.5) | 800 (58.4) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–3]Happiness | 26.80 | <.001 | ||

| Unhappy | 10 (10.6) | 27 (2.0) | ||

| Happy | 84 (89.4) | 1 (98.0) | ||

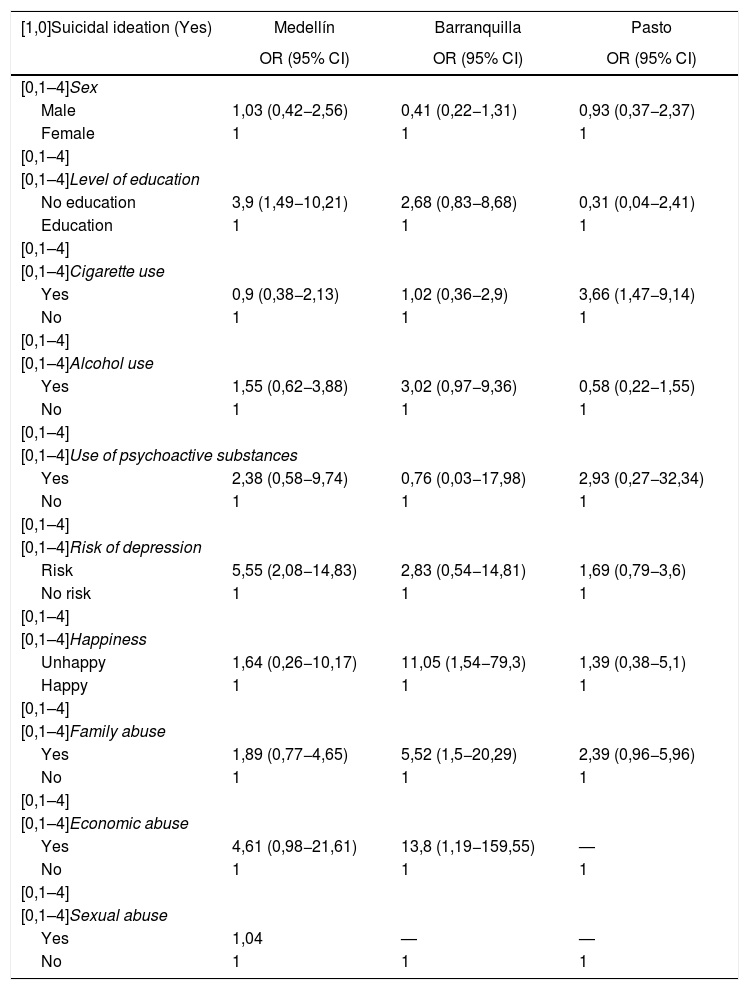

In Medellín, older men had a likelihood of having suicidal thoughts 1.03 times higher than that of women. In addition, older adults without any level of education had a likelihood of suicidal ideation 3.90 times higher than those who did have some level of education. In the three cities, a prevalence of suicidal ideation was found in older adults who smoked cigarettes. Notably, in Pasto, cigarette use was determined to be significant and to increase the likelihood of suicidal ideation by 3.66 times compared to older adults who did not smoke cigarettes. Older adults in Barranquilla who drank alcohol had a likelihood of having suicidal thoughts 2.02 times higher than those who did not drink alcohol. In Pasto, rates of suicidal thoughts were found to be 2.93 times higher in adults using psychoactive substances than in those not having used them (Table 5).

Proportional distribution and factors associated with suicidal ideation in older adults in 3 cities in Colombia, 2016.

| [1,0]Suicidal ideation (Yes) | Medellín | Barranquilla | Pasto |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| [0,1–4]Sex | |||

| Male | 1,03 (0,42−2,56) | 0,41 (0,22−1,31) | 0,93 (0,37−2,37) |

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Level of education | |||

| No education | 3,9 (1,49−10,21) | 2,68 (0,83−8,68) | 0,31 (0,04−2,41) |

| Education | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Cigarette use | |||

| Yes | 0,9 (0,38−2,13) | 1,02 (0,36−2,9) | 3,66 (1,47−9,14) |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Alcohol use | |||

| Yes | 1,55 (0,62−3,88) | 3,02 (0,97−9,36) | 0,58 (0,22−1,55) |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Use of psychoactive substances | |||

| Yes | 2,38 (0,58−9,74) | 0,76 (0,03−17,98) | 2,93 (0,27−32,34) |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Risk of depression | |||

| Risk | 5,55 (2,08−14,83) | 2,83 (0,54−14,81) | 1,69 (0,79−3,6) |

| No risk | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Happiness | |||

| Unhappy | 1,64 (0,26−10,17) | 11,05 (1,54−79,3) | 1,39 (0,38−5,1) |

| Happy | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Family abuse | |||

| Yes | 1,89 (0,77−4,65) | 5,52 (1,5−20,29) | 2,39 (0,96−5,96) |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Economic abuse | |||

| Yes | 4,61 (0,98−21,61) | 13,8 (1,19−159,55) | — |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Sexual abuse | |||

| Yes | 1,04 | — | — |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

In older adults with suicidal ideation in Medellín, statistical significance was found for older adults with a risk of depression; this increased the likelihood of suicidal thoughts appearing in this population by 4.55 times. Unhappiness in Barranquilla increased the likelihood of suicidal thoughts in older adults by 11.05 times, with statistical significance. In that same city, abuse among family members of older adults was significant (P = .01), and this characteristic increased the likelihood of thoughts of self-destruction in older adults by 5.52 times. Economic abuse increased the likelihood of suicidal thoughts in older adults in Barranquilla by 13.80 times (P = .04), and in Medellín sexual abuse was found to increase the likelihood of suicidal thoughts by 1.04 times compared to older people who had not been subjected to this type of abuse (Table 5).

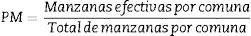

Factors that account for suicidal ideation in older adultsFollowing logistic regression in search of factors accounting for suicidal ideation in older adults in this study, sexual abuse emerged as the primary factor, followed by economic abuse, poor personal relationships among the older adult's family members and risk of depression.

Older adults who were sexually abused were found to have a 33.2 times greater likelihood of having such thoughts than those who were not abused. Following adjustment, it was found that the relationship had been underestimated, as this type of abuse increased the likelihood of having suicidal thoughts by 14.7 times, and, after adjustment, this factor became 33.3. In addition, when older adults were economically abused, their likelihood of having suicidal thoughts was 3.5 (95% CI: 1.019–12.141) times higher than that of older adults who did not suffer from this type of abuse. This relationship was overestimated, since economic abuse increased suicidal ideation by 5.4 times, but when it was adjusted with all the other variables, the probability of frequency became 3.5.

When older adults had poor relationships with family members, their likelihood of suicidal thoughts was 3.0 (95% CI: 1.521–5.968) times that of older adults with good personal relationships with family members. This relationship was overestimated, since poor relationships with family members increased suicidal ideation by 5.6 times, but once adjusted along with all the other variables, the probability of frequency became 3.0. With respect to risk of depression in older adults, the likelihood of having suicidal thoughts was 2.1 (95% CI: 1.187–3.822) times that of those not at risk of suffering from depression. For older adults who experienced discrimination, a probability of contemplating suicide 1.6 (95% CI: 0.948–2.927) times higher than that of those who did not report any sort of discrimination was found (Table 6).

Gross and adjusted analysis of suicidal ideation in older adults in 3 cities in Colombia, 2016.

| [1,0]Variables | Gross analysis | Adjusted analysis |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| [0,1–3]Occupation or profession | ||

| Informal job | 1,79 (1,05−3,03) | 066 (0,37−1,18) |

| Other | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Toxic habits | ||

| Cigarette use | 2,1 (1,37−3,22) | 1,61 (0,97−2,66) |

| Alcohol use | 1,61 (1,06−2,45) | 1,18 (0,7−1,97) |

| Psychoactive substance use | 3,37 (1,58−10,05) | 2,56 (0,88−7,4) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Depression | ||

| Risk of depression | 3,79 (2,4−5,99) | 213 (1,19−3,82) |

| No risk of depression | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Disability | ||

| Any disability | 1,59 (1,02−2,46) | 1,49 (0,92−2,42) |

| No disability | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Quality of life | ||

| Dissatisfied | 3,26 (2,04−5,19) | 1,19 (0,6−2,36) |

| Satisfied | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Health | ||

| Dissatisfied | 2,61 (1,69−4,02) | 1,34 (0,73−2,45) |

| Satisfied | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Economic situation | ||

| Dissatisfied | 1,98 (1,3−3,03) | 0,99 (0,59−1,67) |

| Satisfied | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Happiness | ||

| Unhappy | 5,92 (2,77−12,63) | 1,86 (0,7−4,94) |

| Happy | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Family relationships | ||

| Poor | 4,05 (2,48−6,62) | 1,5 (0,76−2,94) |

| Good | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Personal relationships among family members | ||

| Poor | 5,56 (3,42−9,06) | 3,01 (1,52−5,97) |

| Good | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Social support | ||

| Limited | 3,01 (1,73−5,22) | 0,74 (0,36−1,54) |

| Adequate | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Abuse | ||

| Yes | 2,54 (1,49−4,35) | 0,73 (0,36−1,48) |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Economic abuse | ||

| Yes | 5,44 (1,92−15,44) | 3,52 (1,02−12,14) |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Sexual abuse | ||

| Yes | 14,71 (0,91−237,05) | 33,2 (1,56−708,94) |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Discrimination | ||

| Yes | 2,75 (1,71−4,42) | 1,67 (0,95−2,93) |

| No | 1 | 1 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Analysis adjusted by variables: occupation, toxic habits, depression, disability, quality of life, health, economic situation, happiness, interactions among family members, personal relationships among family members, social support, economic abuse, sexual abuse and discrimination.

The prevalence of suicidal ideation in older adults found in this study was 6.4%, lower than that reported by Silva et al.,12 i.e. 12.2% of those over 65 years of age in Chile, and similar to that recorded in Colombia, specifically 6.5% of those over 45 years of age.30 It is important to recognise that these differences lie not only in how information is acquired, but also in the cultural, social, economic and governmental context of each country. Furthermore, it should be taken into consideration that the public health surveillance system in Colombia is focused on reporting suicide attempts, but does not enquire into suicidal ideation.44

With the multivariate analyses, following adjustment for the rest of the variables, it was found that when older adults had an informal job the probability of frequency was overestimated; this result was similar to that reported by Lee,45 as having some sort of income at home is a protective condition against suicidal thoughts for older adults. Another study16 indicated that adults without an occupation had a 2.6 times higher likelihood of contemplating taking their own lives. The fact is that for people over 60 employment opportunities in Colombia are quite limited; this would indicate that having some sort of occupation makes people feel useful and occupies their time, thus distancing them from suicidal thoughts.

Abuse was a condition associated with suicidal ideation. A study of older adults in rural areas in China46 found that in women the likelihood of ideation increased by 4.5 times with physical abuse, by 5 times with psychological abuse, by 1.6 times with elder abuse and neglect, by 4.1 times with economic abuse and by 4.7 times with sexual abuse. These results were similar to those found in this study, with the exception of sexual abuse, as in this study it increased the likelihood of suicidal thoughts by 3.3 times. This condition is very important, since in general abusers are close to those whom they abuse. Sexual abuse of older adults is a problem that requires a great deal more attention.

Use of cigarettes, alcohol and psychoactive substances was associated with suicidal ideation in the bivariate analysis and multivariate analyses; several studies have reported similar results,12,47 which would suggest that the individuals tend to seek solace in alcohol and other substances that distance them from their reality.

Having any disability was a condition that increased the likelihood of suicidal ideation. Other studies have reported that having limited mobility or being confined to bed increased the risk of ideation by 2.14 times.48 This would suggest that when older adults have a disability that interferes with their ability to go about their daily activities, they may contemplate ending their own lives. However, when the variable was adjusted in the multivariate model, the probability of frequency was found to have been overestimated.

Being dissatisfied with one's health was a characteristic that increased the likelihood of suicidal ideation by up to 2.6 times in this study. A publication from Universidad Javeriana [Javeriana University] reported that people's physical health is associated with suicidal ideation, and a poor state of health may increase the likelihood of suicidal ideation by up to 15.1 times49; that likelihood is higher than the one found in this study, possibly because Universidad Javeriana's population had been diagnosed with a physical or mental health problem.

A study conducted by researchers in Hong Kong,50 who analysed 31 studies published from 2000 to 2016 related to suicidal ideation and social relationships in an older adult population, found that in this population troubled relationships increased the likelihood of suicidal ideation by 1.57 times, and elder abuse increased the likelihood of this condition by 2.31 times. Social relationships are essential for adults' mental and psychological health; however, limited studies have explored this subject.

Factors accounting for suicidal ideation in this study were sexual abuse, poor relationships among family members and risk of depression. These results were similar to those of a study conducted in Australia,10 which reported that poor personal relationships, refraining from social activities, lack of a job and having depressive feelings were factors that explained suicidal ideation in the older adult population. Each study used different scales for determining risk of depression and social interaction. A Korean study found a connection between depressive disorders and suicidal thoughts51 and concluded that depression is a factor that influences suicidal thoughts. For this study, data were collected retrospectively; this may have resulted in an information collection bias, as it must be borne in mind that the older adults may have withheld potentially important information.

The study's manner of enquiring about suicidal ideation is considered to be a limitation thereof, due to the lack of a scale that measures thoughts of self-destruction and suicidal behaviour in Colombia.

The social value of this study is a strength, since it deals with a somewhat overlooked population. It also sheds light on a largely unexplored and preventable problem.

ConclusionsThis study identified factors associated with suicidal ideation in the older adult population in three cities in Colombia. Sexual abuse was the factor that left older adults most at risk of suicidal thoughts. Older adults who suffer from sexual abuse may feel vulnerable in this situation, as most of the time their aggressors are people close to them or members of their family who take advantage of their lack of autonomy. This abuse takes the form of demanding sexual relations from older adults or touching their genitals without their consent.

In Colombia, information on suicidal ideation in older adults is scarce; hence, this study and its results serve as a baseline for future studies. They also enable effective health promotion strategies for this population to be developed and implemented.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Universidad CES and all the researchers involved in the macro project for supplying the database, and Prof. Felipe Tirado for providing timely support and reviewing this article.

Please cite this article as: Ramírez Arango YC, Flórez Jaramillo HM, Cardona D, Segura Cardona ÁM, Segura Cardona A, Muñoz Arroyave DI, et al. Factores asociados con la ideación suicida del adulto mayor en tres ciudades de Colombia, 2016. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:142–153.

Article based on an academic thesis by the authors to earn a Master's Degree in Public Health in 2017 from Universidad CES [CES University].