Suicidal behaviour is a global public health problem, and one population group with high prevalence rates is medical students, especially in the ideation component. Various models have tried to explain it, but there are few inferential studies in the Colombian population. The structural equation models used in controlled social sciences to explain this problem and their analytical power allow generalisations to be made with a certain degree of precision. These analyses require a large amount of data for robust estimation, which limits their usability when there are restrictions to access the data, as is the case today due to Covid-19, and a question that stands out in these models is the evaluation of the fit. Through a set of 1,200 simulated data, an appropriate model fit was found (x5242 = 1.732,300, p < 0,001, CFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.04[0.042-o.046], SRMR = 0.06) for the predictors of depression and perceived burdensomeness, which were analysed using the JASP program. The role of thwarted belongingness is discussed, as well as the appropriateness of the assessment instrument used to evaluate it an considerations regarding suicidal ideation monitoring, evaluation and intervention in medical students.

La conducta suicida es un problema de salud pública mundial, y una población en la que se presentan altos índices de prevalencia es la de estudiantes de Medicina, especialmente en el componente de ideación. Diversos modelos han intentado explicarla, pero son pocos los estudios inferenciales en población colombiana. Los modelos de ecuaciones estructurales utilizados en ciencias sociales resultan apropiados para explicar este problema y su poder analítico permite realizar generalizaciones con cierto grado de precisión. Estos análisis requieren una gran cantidad de datos para una estimación robusta, lo que limita su utilidad cuando hay restricciones para acceder a los datos, como sucede actualmente a causa de la COVID-19, y una cuestión que destaca en estos modelos es la evaluación del ajuste. Mediante un conjunto de 1.200 datos simulados, se encontró un adecuado ajuste del modelo a los datos (x5242 = 1.732,300, p < 0,001; CFI = 0,97; GFI0 = 0,97; TLI = 0,97; RMSEA = 0,04 [0,042-0,046]; SRMR = 0,06) para los predictores depresión y carga percibida, cuyos análisis se realizaron en el programa JASP. Se discute el papel de la pertenencia frustrada, la conveniencia del instrumento para evaluarla y consideraciones de seguimiento, evaluación e intervención de la ideación suicida en estudiantes de Medicina.

Suicidal behaviour is a complex public health problem that has primarily affected adolescents and young adults around the world for years,1 and Colombia is no exception.2 One of its components is suicidal ideation, which is understood to be the first sign expressed through having ideas or thoughts of causing intentional harm to oneself in order to cause death, but not acting on them in any way.3,4 Even so, it has significant individual, familial, social and public health-related implications that grow more complex in the presence of other variables that may contribute to preparing a suicide plan or even carrying it out.

In the general Colombian population, 7.4% of adults over 18 years of age have had suicidal ideation (5.5% of men and 7.6% of women).5,6 It is one of the most commonly studied signs of suicidal behaviour in adolescents and university students in Colombia.7 The cognitive and affective components of taking one's own life and preparing a plan to do so are parts of the passive stage of ideation, which may later manifest as active consideration, planning, preparation and suicide itself. This is precisely why ideation has been a focus of attention as a suicide risk.4,8

The risk factors associated with suicidal behaviour are depressive disorder (36.7%), having an organised plan for suicide (19.7%) and alcohol abuse (11.9%); however, others are also significant, such as having a family history of suicidal behaviour, violence or abuse, bipolar disorder, personality disorder and schizophrenia, each with a prevalence of <10%.2 Two of these factors stand out: depression and suicide attempt planning.

These risk factors are consistent with those found in medical students, a population group that has been extensively studied due to its vulnerability to suicidal behaviour. In various countries, the main variables associated with suicidal ideation in this population are depression, with a prevalence of 6.1% to 13.5%,9–13 and chronic stress, a stressful lifestyle or burnout related to one's career;10,14,15 between 58% and 82% of students suffer from these conditions.10 Other factors associated with suicidal ideation, at lower rates, are psychoactive substance use and alcohol use.16,17 The studies cited have found that the prevalence of suicidal ideation is 5.9%-35.6% in medical students17–20 and that, among those who have had suicidal ideation and prepared a plan, 75% made at least one suicide attempt, while 17% of those without a plan also made at least one attempt.19

In Colombia, the associated variables that have been reported in this population are: clinically significant symptoms of depression, history of psychoactive substance use and perceived fair or poor academic performance in the past year. The prevalence of at least one instance of suicidal ideation over the course of one's life was 15.7%, and 5% reported having attempted suicide at least once.21 Although various studies on ideation have been conducted in Colombia, the subject has seldom been examined in medical students. This represents an opportunity to expand the knowledge in this area. Findings around the world indicate that this population is at high risk of suicidal behaviour; some researchers have even asserted that the risk in medical students is higher than in the general population. Hence, there is a need to propose and evaluate an explanatory model of suicidal ideation in medical students.

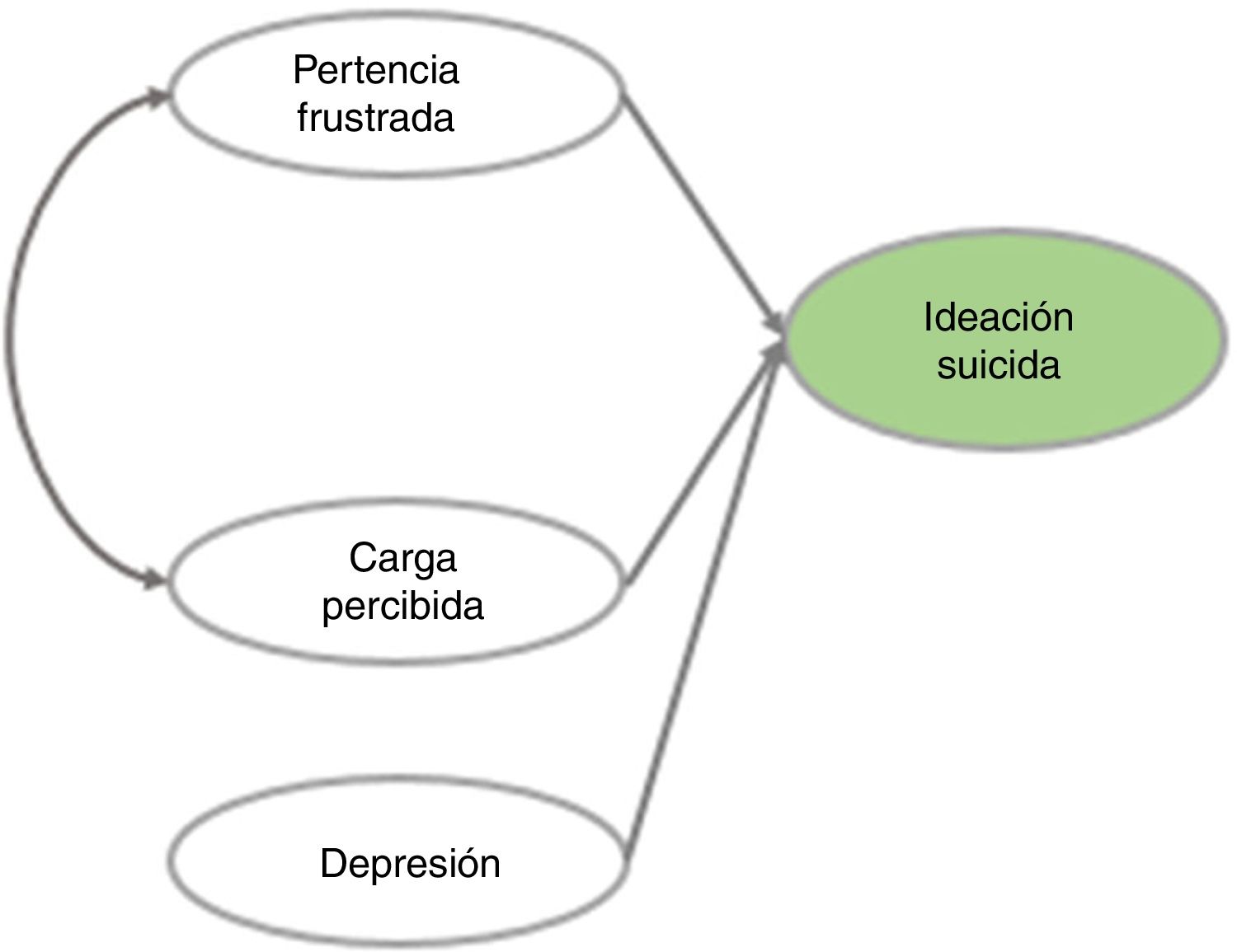

The fundamentals of the interpersonal theory of suicide (IPTS) proposed by Thomas Joiner were used for this study's object model. According to this theory, suicidal behaviour is seen under these two conditions: a) perceived burdensomeness, referring to a sense of being a burden on one's loved ones and/or society (its first-order indicators are: distress due to homelessness, distress due to incarceration, distress due to unemployment, distress due to physical disease, unwanted expendability, belief that one is a burden on one's family, low self-esteem, guilt, shame and agitation), and b) thwarted belongingness, which is the feeling of not belonging to the main groups of reference or value for the person in question and being disconnected (its first-order indicators are: loneliness, lack of mutually constructed relationships, lack of interventions to increase social contact, the effects of seasonal changes, lack of a partner/family, living alone or having little social support, being retired, having been deprived of freedom, domestic violence, loss due to death or divorce, child abuse and family conflicts). In addition, to attempt suicide or die by suicide, a third condition must be present: acquired capability, which is the power to carry out actions to take one's own life.22 Based on this, suicidal ideation would be explained by perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, while suicidal intent would also be explained by perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness as well as by acquired capability.22–26 For purposes of this study's model, only the suicidal ideation part was used.

This theory reaffirms the notion that, in both clinical populations and the general population, compared to suicidal ideation, suicide attempts are less common and deaths by suicide are far less common.23 However, the IPTS was developed in the context of the United States, and several of the indicators that support its main constructs are particular to that country's culture (such as the effects of seasonal changes). Although it has been widely studied and validated in different countries,2–29 there are no known studies showing whether it also explains suicidal behaviour in the Colombian population. Therefore, this study sought to address this matter, specifically in medical students with the inclusion of depression, since the evidence points to depression as the risk factor that explains suicidal ideation the most (Fig. 1).

This proposal is based on structural equation modelling (SEM). This has been extensively used to explain and represent complex social phenomena involving different independent variables that, by their very nature, cannot be directly observed, but are inferred based on indicators, with relationships of various types represented by a flow chart.30 Essentially mathematical, they also enable estimation of several types of relationships at the same time and determine whether they fit the data as a whole.

For the model estimation in Fig. 1, it was not possible to collect data as planned in early 2020, since the COVID-19 pandemic altered study, work and living dynamics. Collecting data in the course of this historical event would have threatened the internal validity of the study, since the variables to be measured were not in their natural state.31 For this type of study on suicidal behaviour, it would not have been adequate to ensure that the results obtained enabled inferences in the proposed model; therefore, a simulation study was conducted with the objective of evaluating an explanatory model of suicidal ideation in medical students based on a set of data for this model's variables.

MethodsSimulation has been widely used to model complex real-world relationships that cannot always be evaluated in research with real data, and are particularly used in research on operations, social sciences, natural sciences and engineering. Simulation conducts a numerical evaluation of a model and collects information to identify the model's true characteristics, thus enabling questions of interest about this representation to be answered.32 Examples of these include simulation studies of human behaviour in emergency situations,33 the effects of percentages of variance on patterns of correlation in measures of student learning,34 estimates of regression parameters35 and evaluation of an estimation accuracy fit index that compares its efficacy to the fit indices commonly used in model estimation.36 Given the COVID-19 pandemic, as mentioned, this alternative offered a means of examining the model proposed in this study.

Data simulationA total of 1,200 data were simulated for 38 variables (Appendix A) making up the four constructs of the proposed model. These data are indicators of latent variables (21 for depression, five for perceived burdensomeness, eight for suicidal ideation and four for thwarted belongingness), for which a database of 400 real records corresponding to members of the university student population in Colombia, including medical students, was used. The simulation was performed using the SPSS v. 26 software program.37 For this, the distribution of the real data was taken into account; however, the relationships between the variables were not forced, as doing so might have biased the model's goodness of fit.

InstrumentsScores for the items from three psychometric instruments were used: the Spanish version of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ-9-S), which evaluates the constructs of perceived burdensomeness (five items) and thwarted belongingness (four items) on a 0-7 scale and has fit indices in the university student population in Colombia (comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.97-0.99; Tucker–Lewis index [TLI] = 0.96-0.98; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.03-0.04 and standardised root mean squared residual [SRMR] = 0.04-0.05);24 the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), which evaluates symptoms of depression in 21 items with a scale of 0-3 points and has fit indices in the university student population in Colombia (RMSEA = 0.055; SRMR = 0.048; α = 0.91);38 and the Positive and Negative Suicidal Ideation (PANSI) inventory, from which only eight items from the negative scale were taken as they were those of interest in this study, with a 5-point scale (α = 0.89).39

Data analysisTo start, the model was verified to be identifiable — that is, to have more observable variables than parameters to be estimated. In order to achieve this, the following formula was used: t≤pp+12, where t represents the parameters to be estimated and p represents the number of observable variables.40 Next, the distribution of the data was reviewed using the Shapiro–Wilk test to identify the best possible estimator. Based on this information, estimates were made using diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS), which has been shown to provide more accurate parameter estimates and a more robust model fit with variables that have neither a normal nor a categorical distribution,41 as was the case of the variables simulated in this study.

The fit of the model to the data from each instrument used was verified to measure the latent variables of the model of suicidal ideation using confirmatory factorial analysis. Both for these and for the overall model, the indices in Table 1 were taken into account;42 these were calculated in JASP, ver. 0.12.2, an open-source software program for statistical analysis, using the lavaan package for modelling structural equations.43 The script for the overall model is also found in Appendix A.

Criteria for fit indices.

| Fit index | Moderate fit | Good fit |

|---|---|---|

| p (χ2) | 0.01-0.05 | 0.05-1.00 |

| CFI | 0.95-0.97 | 0.97-1 |

| GFI | 0.90-0.95 | 0.95-1 |

| TLI | 0.95-0.97 | 0.97-1 |

| RMSEA | 0.05-0.08 | ≤ 0.005 |

| SRMR | 0.05-0.1 | ≤ 0.005 |

From Schermelleh-Engel et al.42

The objective of this study was to evaluate an explanatory model of suicidal ideation in medical students; for this purpose, 1,200 data were simulated based on a dataset for the variables of the model. The descriptive data are presented in Appendix B. As in the real data, the simulated variables showed a non-normal statistical distribution (p < 0.001).

Confirmatory factorial analysis of each latent variable in the overall model reported good fit indices, thus ensuring that said constructs were measured appropriately (Appendix A). The model (Fig. 2) showed a suitable fit to the data (x6592 = 2.556,250; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.96; goodness-of-fit index [GFI] = 0.96; TLI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.05 [0.047-0.051]; SRMR = 0.07), confirming the existence of a positive and moderate relationship between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (r = 0.05; p < 0.001). However, thwarted belongingness was not found to have a direct effect on suicidal ideation (p > 0.05); by contrast, the perceived burdensomeness and depression variables were found to have a direct effect on ideation.

With the goal of testing a more parsimonious model, a second model was estimated to explain suicidal ideation (Fig. 3). The thwarted belongingness variable was not included in it, and a good fit to the data was again found (x5242 = 1,732, 300; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.97; GFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.04 [0.042-0.046]; SRMR = 0.06). This reaffirmed the direct effects of perceived burdensomeness and depression on suicidal ideation (p < 0.001) in the simulated dataset.

Comparison of the models (Table 2) revealed that statistically the model better fit the data when the thwarted belongingness variable was removed. Nevertheless, the relationship that exists between thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness should not be overlooked.

DiscussionThe main objective of this study was to evaluate an explanatory model of suicidal ideation in medical students, a population group of interest given its high reported prevalence rates17–20 and its concentration of ages at which the highest numbers of suicide attempts and suicides are found, both around the world1 and in Colombia.2 Due to the difficulty of collecting data in the population of interest during the COVID-19 pandemic, data were simulated to evaluate the proposed model, for the purpose of identifying its characteristics and making an approximation that would answer some questions of interest, as simulation studies permit.32

Two models were evaluated to identify their fit to the data; the results showed a good fit in both cases. An initial finding in this regard consisted of tentative identification of the variables that might explain suicidal ideation: depression and perceived burdensomeness. This was supported not only by the numerical approach taken, but also by the IPTS and the available scientific evidence, which has shown depression to be the main risk factor for suicidal ideation in medical students. A second finding was that both models were estimable and when they were evaluated with simulated data from a real dataset and the relationships described were found, there was a certain degree of confidence that same relationships would be found in real data in the population of interest in this study. This must be confirmed in subsequent studies.

Regarding model 1, perceived burdensomeness and depression explained suicidal ideation, but thwarted belongingness did not contribute to this explanation. This finding was consistent with the studies in a systematic review on IPTS predictors that found the relationship between thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in suicidal ideation to be significant: a) when levels of perceived burdensomeness are high, b) when levels of thwarted belongingness are high or c) by age group. In that same study, 55 tests were performed to determine the effect of thwarted belongingness on suicidal ideation; of these, just 22 (40%) proved significant. It was also found that, in 82.6% of the studies, perceived burdensomeness statistically explained suicidal ideation (with an explained variance of 36%-41%, higher than the variance in this study); this was confirmed in different contexts such as hospitals, mental health clinics and schools.29 These findings were consistent with the exclusive association found in thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation in a clinical sample of adults, which was significant when the prevalence of ideation was high.44 This information is of particular interest in designing intervention strategies.

However, in the case of the population of interest in this study, it can also be inferred that thwarted belongingness does not explain suicidal ideation because it features indicators that do not apply to this population's life stage, such as being retired, having been deprived of freedom and living with a partner, as well as the effects of seasonal changes, which do not apply to the Colombian population. This is contrary to what might occur with perceived burdensomeness, the indicators of which may better represent conditions in medical students.

Regarding model 2, which showed a better fit to the data and, with it, greater explained variance of suicidal ideation (31%), it was proposed that thwarted belongingness might not be taken into account as a direct predictor. However, the relationship between thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness could not be denied; therefore, another type of relationship that better fits the characteristics of medical students, a population in which this theory has seldom been studied, should be considered. Some researchers have found thwarted belongingness to play a mediator role in the relationship between other variables and suicidal ideation.29,45,46

A more comprehensive explanation of the findings of this study is supported by the instrument used to measure perceived burdensomeness and frustrated belonging. The original INQ had 25 items;47 however, over the course of various psychometric validation studies, adjustments were made, resulting in fewer items for both constructs. This was the case of the Spanish version of the INQ, developed for the Spanish-speaking population; a nine-item version derived from said version24 was used in this study. In it, four items measure thwarted belongingness, a construct that theoretically has 12 observable indicators; hence, one explanation of the results obtained is that these items may not be sufficient to measure the construct in its entirety.

The main limitation of this study was that the findings were based on simulated data. Although the simulated variables had a distribution similar to that of the real dataset, this did not ensure the relationships found in the populations of interest, since the variability of the data may change depending on the sociodemographic characteristics of the subjects. In addition, the proposed model may represent the general university student population, but not necessarily be specific to medical students, since only one risk factor reported in the evidence for this population, depression, was taken into account; however, it may be that other variables accounting for the phenomenon were not taken into consideration in this study due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The results of this study reveal the need to conduct comparative and explanatory studies on suicidal ideation in medical students in comparison to the general population. Such studies would allow for not only a better understanding of the phenomenon based on scientific evidence of a key public health problems in Colombia and around the world, but also decision-making based on that evidence for promotion, prevention, early detection, diagnosis, intervention, treatment and rehabilitation in mental health, as demanded by Law 1616 of 2013 on suicide and depression, which appears to be the main risk factor for suicide.48 The global literature does unanimously agree that medical students comprise an at-risk group. The surveillance system in Colombia monitors at-risk populations,49 and it would be worthwhile to include these students as a vulnerable group.

Further psychometric studies that determine the sufficiency of the items for the evaluation of the thwarted belongingness construct in this population are also needed. The evaluation practices required by the psychologist's deontological code stipulate that the use of psychometric tests must be supported by scientific procedures that account for the reliability and validity in the population in which they will be used.50 It must also be added that various factors within this framework can alter the variance attributed to the construct and the variance of other sources, such as the population in which the data were collected and the adaptation and translation of the test,51 thus reaffirming the need for these studies. Adequate evaluation will allow for effective identification of intervention needs in each case.

Finally, suicide as a public health problem is in itself among the most pressing challenges faced by all health professionals, as thousands of people die by suicide every year. It is crucial to understand the complex phenomenon that it represents, and it is even more crucial to promote effective interventions that mitigate the damage caused by explanatory factors and to provide those affected with tools to find meaning in life. The IPTS22,23 predicts that the outcomes of suicide crises, both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, depend on developing stronger connections to others (the opposite of thwarted belongingness), as well as a stronger sense of making significant contributions that benefit others (the opposite of perceived burdensomeness). This renders the theory particularly important in this study, as it not only explains suicidal behaviour, but also allows for establishment of prevention and intervention guidelines, especially for mental health.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

To Dr Juan David Leongómez, a researcher from Universidad El Bosque [El Bosque University], for his contributions to data simulation and promotion of open science.

https://osf.io/jhw5c/?view_only=27885be8ab03429fbba06b4fc98b6ae9

| M | SD | β Model 1 | Model 1 standard error | β Model 2 | Model 2 standard error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (BDI-II) | ||||||

| Item 1 | 0.384 | 0.614 | 0.695 | <0.001 | 0.677 | <0.001 |

| Item 2 | 0.438 | 0.614 | 0.576 | 0.051 | 0.568 | 0.052 |

| Item 3 | 0.228 | 0.474 | 0.555 | 0.051 | 0.542 | 0.052 |

| Item 4 | 0.618 | 0.713 | 0.501 | 0.056 | 0.497 | 0.057 |

| Item 5 | 0.704 | 0.831 | 0.411 | 0.070 | 0.419 | 0.072 |

| Item 6 | 0.180 | 0.533 | 0.374 | 0.054 | 0.375 | 0.055 |

| Item 7 | 0.361 | 0.755 | 0.632 | 0.074 | 0.615 | 0.076 |

| Item 8 | 0.996 | 0.816 | 0.579 | 0.063 | 0.579 | 0.066 |

| Item 9 | 0.394 | 0.618 | 0.677 | 0.059 | 0.676 | 0.061 |

| Item 10 | 0.383 | 0.875 | 0.494 | 0.082 | 0.483 | 0.083 |

| Item 11 | 0.693 | 0.817 | 0.438 | 0.067 | 0.456 | 0.071 |

| Item 12 | 0.828 | 0.917 | 0.612 | 0.080 | 0.607 | 0.084 |

| Item 13 | 0.336 | 0.688 | 0.593 | 0.069 | 0.593 | 0.071 |

| Item 14 | 0.275 | 0.597 | 0.655 | 0.058 | 0.649 | 0.060 |

| Item 15 | 0.988 | 1.02 | 0.600 | 0.087 | 0.614 | 0.090 |

| Item 16 | 1.15 | 0.830 | 0.500 | 0.064 | 0.501 | 0.066 |

| Item 17 | 0.718 | 0.767 | 0.525 | 0.064 | 0.534 | 0.067 |

| Item 18 | 0.976 | 0.978 | 0.399 | 0.079 | 0.415 | 0.084 |

| Item 19 | 0.924 | 0.845 | 0.631 | 0.076 | 0.642 | 0.080 |

| Item 20 | 0.952 | 0.819 | 0.650 | 0.068 | 0.658 | 0.072 |

| Item 21 | 0.142 | 0.472 | 0.226 | 0.040 | 0.208 | 0.041 |

| Perceived burdensomeness (INQ-9) | ||||||

| Item 2 | 1.63 | 1.29 | 0.740 | <0.001 | 0.737 | <0.001 |

| Item 3 | 1.68 | 1.33 | 0.768 | 0.052 | 0.778 | 0.054 |

| Item 4 | 1.40 | 1.20 | 0.781 | 0.041 | 0.780 | 0.042 |

| Item 5 | 1.51 | 1.27 | 0.715 | 0.050 | 0.712 | 0.050 |

| Item 6 | 1.17 | 1.28 | 0.826 | 0.053 | 0.822 | 0.054 |

| Thwarted belongingness (INQ-9) | ||||||

| Item 10 | 2.45 | 1.84 | 0.779 | <0.001 | ||

| Item 13 | 2.22 | 1.88 | 0.688 | 0.061 | ||

| Item 14 | 2.53 | 1.85 | 0.845 | 0.056 | ||

| Item 15 | 2.10 | 1.72 | 0.754 | 0.058 | ||

| Suicidal ideation (PANSI) | ||||||

| Item 1 | 0.389 | 0.867 | 0.732 | <0.001 | 0.755 | <0.001 |

| Item 3 | 0.378 | 0.840 | 0.692 | 0.053 | 0.708 | 0.052 |

| Item 4 | 0.455 | 1.04 | 0.581 | 0.082 | 0.578 | 0.079 |

| Item 5 | 0.443 | 0.933 | 0.719 | 0.054 | 0.744 | 0.053 |

| Item 7 | 2.39 | 1.99 | 0.157 | 0.113 | 0.110 | 0.106 |

| Item 9 | 2.16 | 1.72 | 0.332 | 0.101 | 0.328 | 0.098 |

| Item 10 | 0.320 | 0.745 | 0.689 | 0.054 | 0.707 | 0.053 |

| Item 11 | 0.440 | 0.973 | 0.734 | 0.067 | 0.742 | 0.066 |

M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

All regression weights were statistically significant with p < 0.001.

Please cite this article as: Castro-Osorio R, Maldonado-Avendaño N, Cardona-Gómez P. Propuesta de un modelo de la ideación suicida en estudiantes de Medicina en Colombia: un estudio de simulación. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2022;51:17–24.