To determine the perception that some general clinical practitioners have about depressive syndrome in a region of Colombia.

MethodologyThe qualitative approach was established as a basis for this study using grounded theory for the description, analysis, and interpretation of data collected in 20 semi-structured interviews aimed at general medical practitioners who had treated patients with depressive syndrome in their clinical practice.

ResultsThroughout the interviews, some essential elements are highlighted such as: “seeing beyond a body,” where the interest of the physician is reflected by individualising each patient case because regardless of having the same disease, knowing that not all can be addressed or treated equally. “From insignificant to terrifying” shows that the network of experiences, experiences, emotions, and desires that make up part of the physician, are reflected in the compassion that he has for patient with depression, a situation that makes him confront as a human being before the suffering of others. In contrast appears the “my hands are tied” with a health system that prevents proper care of these patients, and generates problems for the treating physician.

ConclusionsThe malleable and unfinished scenario where the physicians interact with the depressive syndrome, allows them to understand their humanity while reflecting on the possibilities, limitations, meanings, attitudes and actions that they have about this disorder that is reflected in the ability of general physicians to diagnose and treat depression that is not necessarily associated with age or experience in practice. However, errors in care can be reduced with sufficient knowledge and an appropriate approach to mental illness.

Comprender los significados que el síndrome depresivo tiene para algunos médicos generales en ejercicio clínico en una región colombiana.

MétodosSe asumió el enfoque cualitativo como guía para esta investigación utilizando la teoría fundamentada para la descripción, el análisis y la interpretación de 20 entrevistas semiestructuradas dirigidas a médicos generales que hubieran atendido a pacientes con síndrome depresivo.

ResultadosEn las entrevistas resaltan algunos elementos indispensables, como: «ver más allá de un cuerpo», donde se refleja el interés del médico por individualizar cada caso de cada paciente porque, aparte de que tengan la misma enfermedad, sabe que no a todos se debe abordar ni tratar por igual. En «De insignificante a terrorífico» se observa que el entramado de vivencias, experiencias, emociones y anhelos que hacen parte del médico se reflejan en la compasión que este tenga del paciente con depresión, situación que hace que como ser humano afronte el sufrimiento del otro; en contraposición, aparece el «Verse atado de manos» respecto al sistema de salud, que dificulta la adecuada atención de estos pacientes y genera un sinsabor en el médico tratante.

ConclusionesEl escenario maleable e inacabado en el que interactúa el médico con el síndrome depresivo le permite saberse humano mientras reflexiona en relación con cada una de las potencialidades, las limitaciones, los significados, las actitudes y los comportamientos que tiene ante esta entidad nosológica, lo que se ve reflejado en la habilidad de los médicos generales para diagnosticar y tratar la depresión, que no necesariamente se asocia con la edad o la experiencia en la práctica. No obstante, se puede reducir los errores en la atención con un conocimiento vasto y un enfoque apropiado de la enfermedad mental.

Depressive syndrome is considered to be a clinical condition in which a large number of signs and symptoms converge. It has a high prevalence in the general population. It can occur in any age group, and onset can be influenced by a range of different precipitating factors. In view of the complexity of the symptoms, the disability it generates, the subsequent deterioration in people's quality of life and the costs for society, a number of researchers have sought to identify the factors associated with depressive syndrome,1,2 its causes and consequences3 and the most appropriate treatment.

There are a number of factors affecting the quality of care for patients with depressive syndrome in Colombia. Among them are the recognised barriers in the Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud [General System of Social Security in Health]4 which, “despite setting out the principles of equity, obligation, integrality and quality”, has been shown to have difficulties with the system of referral and counter-referral, limitations in the provision of services and insufficient emphasis on programmes for the promotion and prevention of mental health problems.5

Other factors include physicians having insufficient scientific and technical knowledge. The extent of the knowledge deficit has led their academic training in mental health to be called into question,5 as it has been found that in first level care there is a lack of proper diagnosis of mental disorders and initiation of appropriate treatment. The World Health Organisation6 developed the Mental Health Gap Action Programme, aimed at improving and expanding care for mental, neurological and substance use disorders by making them priority conditions.

Given the high rates of depression in Colombia,2 there is no question that all physicians, whether in their personal life or family, social or professional circles, will have had interaction with people suffering from depressive syndrome. Such experiences will have passed through the physician's conscious and subconscious thoughts and led them to form perceptions and interpretations about depressive syndrome. It will be these thoughts that finally determine both their ability to understand and resolve the problems that arise in the clinic, and the quality of the care they provide to people who find their biopsychosocial environments affected by this set of signs and symptoms.7

Several publications have recommended improving intervention in mental disorders through the promotion of mental health and prevention.8–10 There are studies that discuss the social stigma of mental illness and the impact it has on patient care.11 Other studies have examined not only the mentally ill, but also physicians’ communication with patients and its impact on the treatment and treatment adherence.12 Specifically in Colombia, studies have been conducted to assess the capabilities of the physicians and their knowledge about mental illness, the reasons for deficiencies in their skills and the quality of the university education.13–15 Nonetheless, there has been little study of the perception and impact of depression among general practitioners based on their practical and personal experiences.

The aim of this study is to determine the perceptions that general practitioners have of depressive syndrome based on their own experiences. Our goal is to be able to explain these perceptions by examining how the general practitioner behaves when dealing with depressive syndrome and the impact their behaviour produces on the care provided and resolution of the patient's problem.

MethodsUsing a qualitative approach16 and grounded theory techniques,17 accompanied by a continuous literature review, we carried out the description, analysis and interpretation of the data18 obtained from 20 semi-structured interviews19 with people who, up to 2014, had practiced as general practitioners in first and/or second level healthcare services, had minimum experience of one year and would have cared for people with depressive syndrome. They were selected by convenience sampling initially and then by theoretical sampling.17 This study had ethical approval from the National Faculty of Public Health at the Universidad de Antioquia.

The analysis of the data was systematic, interactive and iterative between data, analysis, collection, etc. at three connected time points: the descriptive, the analytical and the interpretive; taking into account the steps developed by Strauss et al.,17 called open coding, axial coding and selective coding, respectively.20

Open coding was used when performing a microanalysis of the data, i.e. a “line by line” analysis of each of the transcripts of the interviews, breaking them down into incidents, ideas, events and significant discrete acts, in view of the objectives of the research; they were then assigned a noun code to represent what had been expressed in the words of the interviewee.17

During the process of conceptualisation and in search of similarities and differences, the emergent codes were compared with those considered conceptually similar in nature or related in the meaning, and more abstract concepts were grouped forming what is known as “descriptive categories”.17

At the end of the first 10 interviews, we identified that some of the categories had little description of their internal attributes. That led to the search for variability in the information and to us finally conducting a second round of interviews based on theoretical sampling. Meanwhile, the descriptive categories were related to each other. This led on to the analytical time point, with which we sought to construct relationships in order to form more precise and complete explanations about the phenomena.17

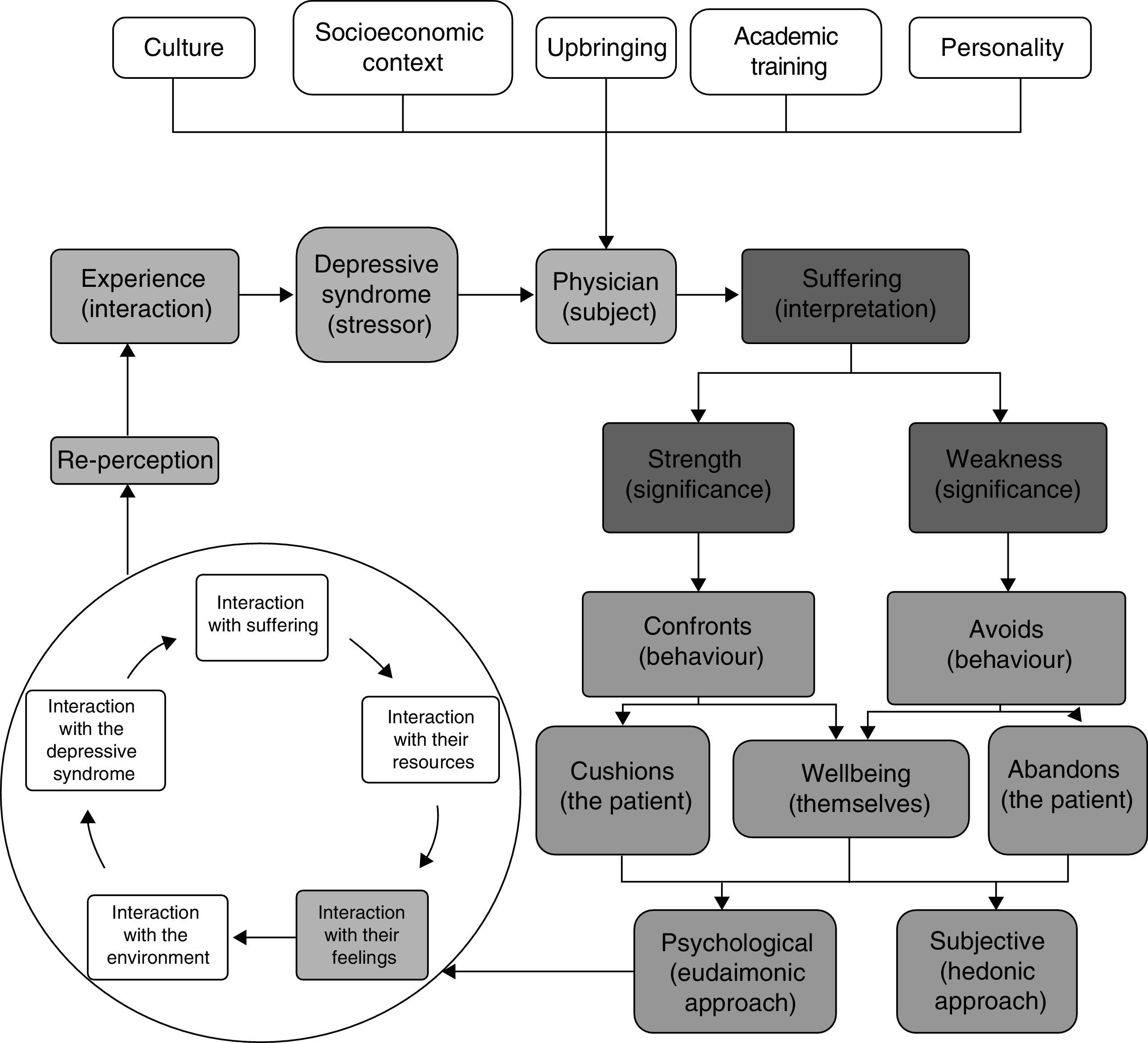

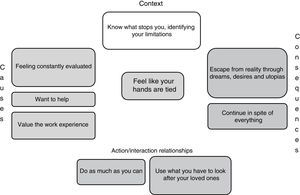

As an essential instrument in coding, we used the “paradigmatic matrix”,17 and with it a complex relationship was achieved between the categories that emerged from open coding, in which some emerged as the phenomenon and others as subcategories that represented the context of that phenomenon, its conditions or causes, the actions/interactions or the consequences of the actions/interactions.

The relationships discerned in the axial coding indicated that there were three significant phenomena or categories that had theoretical saturation,17,21 which led on to the interpretative step of the research or selective coding.

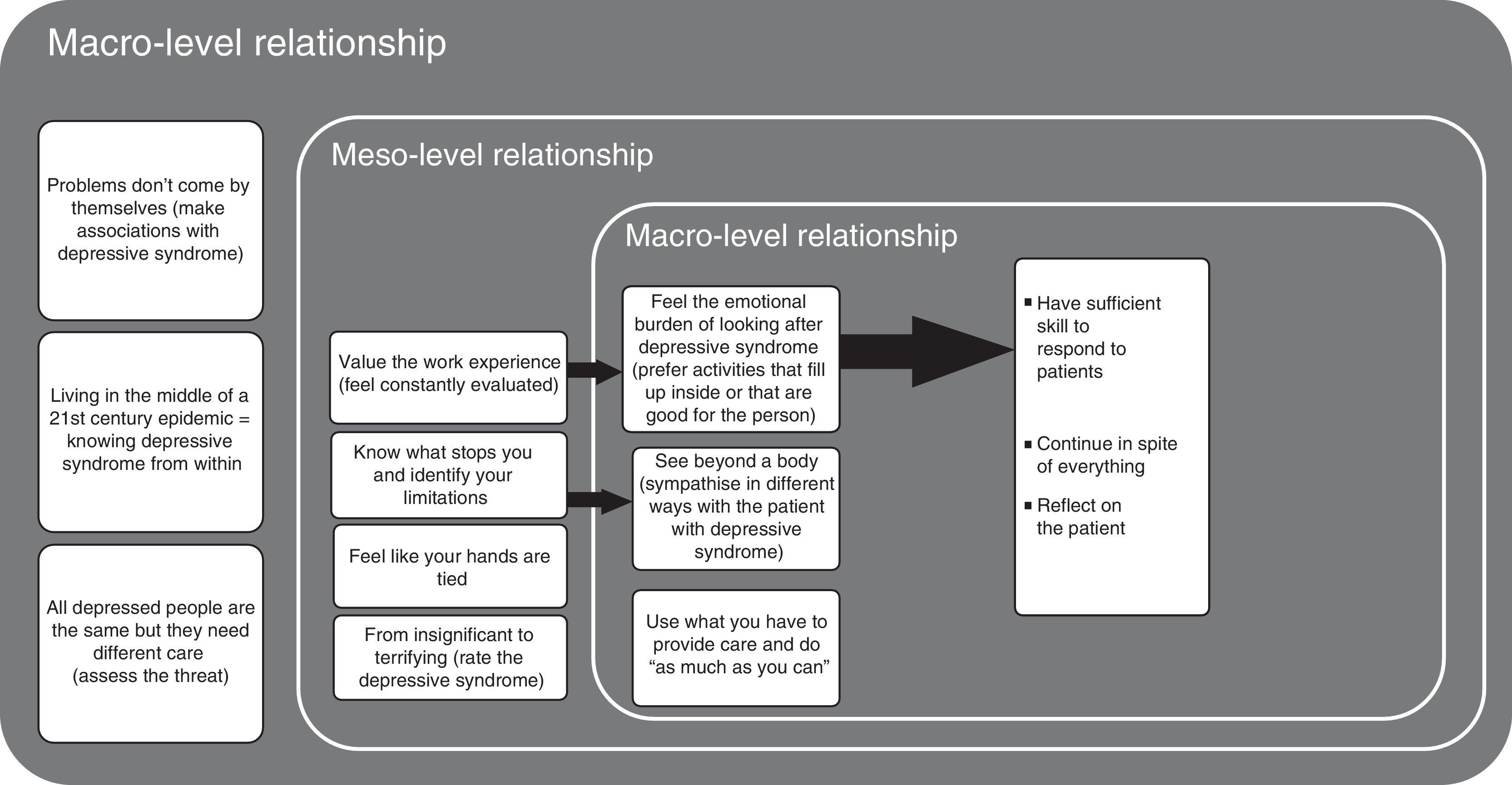

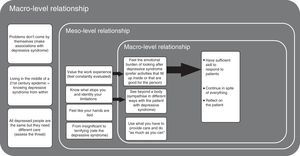

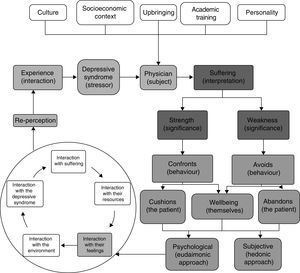

In order to explain the relationship between the provisional analytical categories, different integrative diagrams were elaborated, resulting in a theoretical framework based on the conditional/consequential matrix proposed by the authors,17 which allowed us to reflect and connect elements of the context, causes, consequences and the process of action/interaction at the macro, meso and micro levels of the perception that general practitioners had constructed around depressive syndrome. Lastly, these findings were discussed with a psychiatrist who studied the shortcomings between the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in Colombia in an unstructured interview and in relation to the scientific literature that had been reviewed in the analytical process.

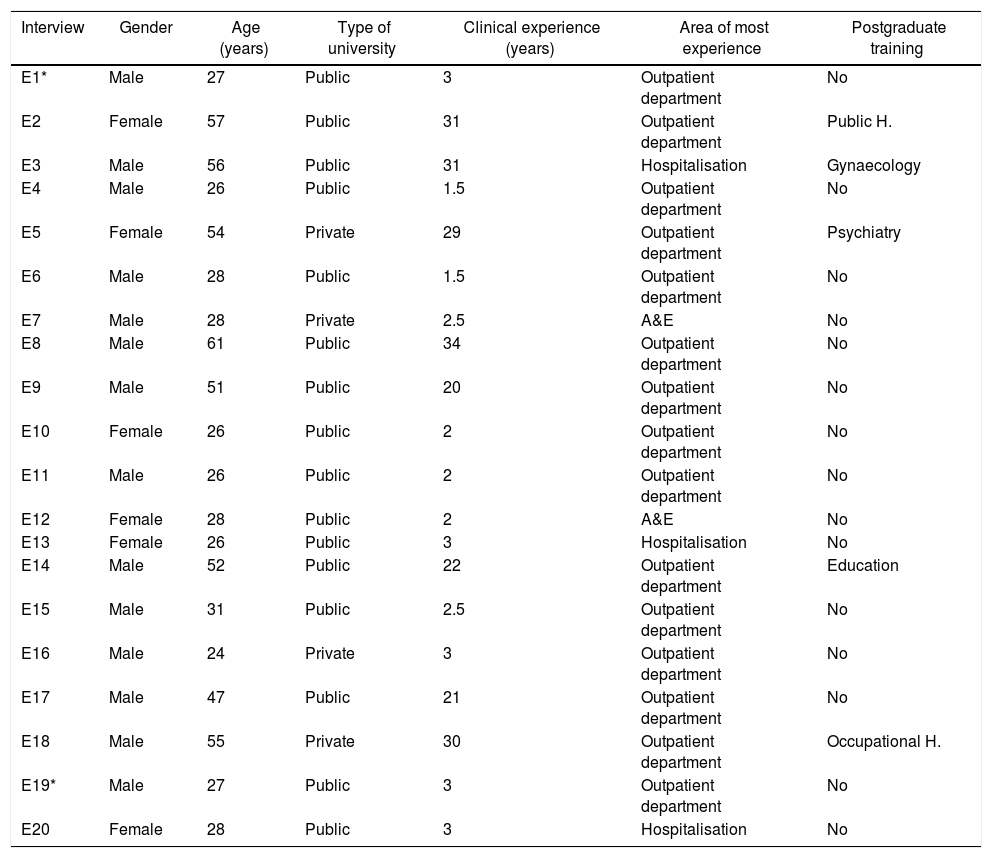

ResultsThis study was completed with 20 interviews obtained from 19 people: 13 males and 6 females. The interviewees were all aged from 24 to 61 (average 38.4). All the interviewees were doctors who had graduated from Colombian universities (15 from public universities and four from private universities), and had an average of 12.8 (range 1.5–34) years of clinical experience. Fifteen of the interviewees stated that the department where they had the most experience was outpatients. In addition to their undergraduate training, five had postgraduate training in Public Health, Occupational Health, Education, Gynaecology and Psychiatry, although it is important to note that their contributions to the interviews were from their experience as general practitioners (Table 1).

Characteristics of the interviewees.

| Interview | Gender | Age (years) | Type of university | Clinical experience (years) | Area of most experience | Postgraduate training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1* | Male | 27 | Public | 3 | Outpatient department | No |

| E2 | Female | 57 | Public | 31 | Outpatient department | Public H. |

| E3 | Male | 56 | Public | 31 | Hospitalisation | Gynaecology |

| E4 | Male | 26 | Public | 1.5 | Outpatient department | No |

| E5 | Female | 54 | Private | 29 | Outpatient department | Psychiatry |

| E6 | Male | 28 | Public | 1.5 | Outpatient department | No |

| E7 | Male | 28 | Private | 2.5 | A&E | No |

| E8 | Male | 61 | Public | 34 | Outpatient department | No |

| E9 | Male | 51 | Public | 20 | Outpatient department | No |

| E10 | Female | 26 | Public | 2 | Outpatient department | No |

| E11 | Male | 26 | Public | 2 | Outpatient department | No |

| E12 | Female | 28 | Public | 2 | A&E | No |

| E13 | Female | 26 | Public | 3 | Hospitalisation | No |

| E14 | Male | 52 | Public | 22 | Outpatient department | Education |

| E15 | Male | 31 | Public | 2.5 | Outpatient department | No |

| E16 | Male | 24 | Private | 3 | Outpatient department | No |

| E17 | Male | 47 | Public | 21 | Outpatient department | No |

| E18 | Male | 55 | Private | 30 | Outpatient department | Occupational H. |

| E19* | Male | 27 | Public | 3 | Outpatient department | No |

| E20 | Female | 28 | Public | 3 | Hospitalisation | No |

From the microanalysis of the data collected in all the interviews, a total of 2632 codes emerged: 1833 from the first round and 799 from the second. The codes resulting from the descriptive phase on the data were grouped by the similarities they showed when compared. These groups of codes produced the descriptive categories (seven in total), each with properties within, which were grouped again and converted into 21 subcategories; these subcategories were related to each other using paradigmatic matrices in the analytical step and a conditional/consequential matrix, which finally included the interpretative process of this study.

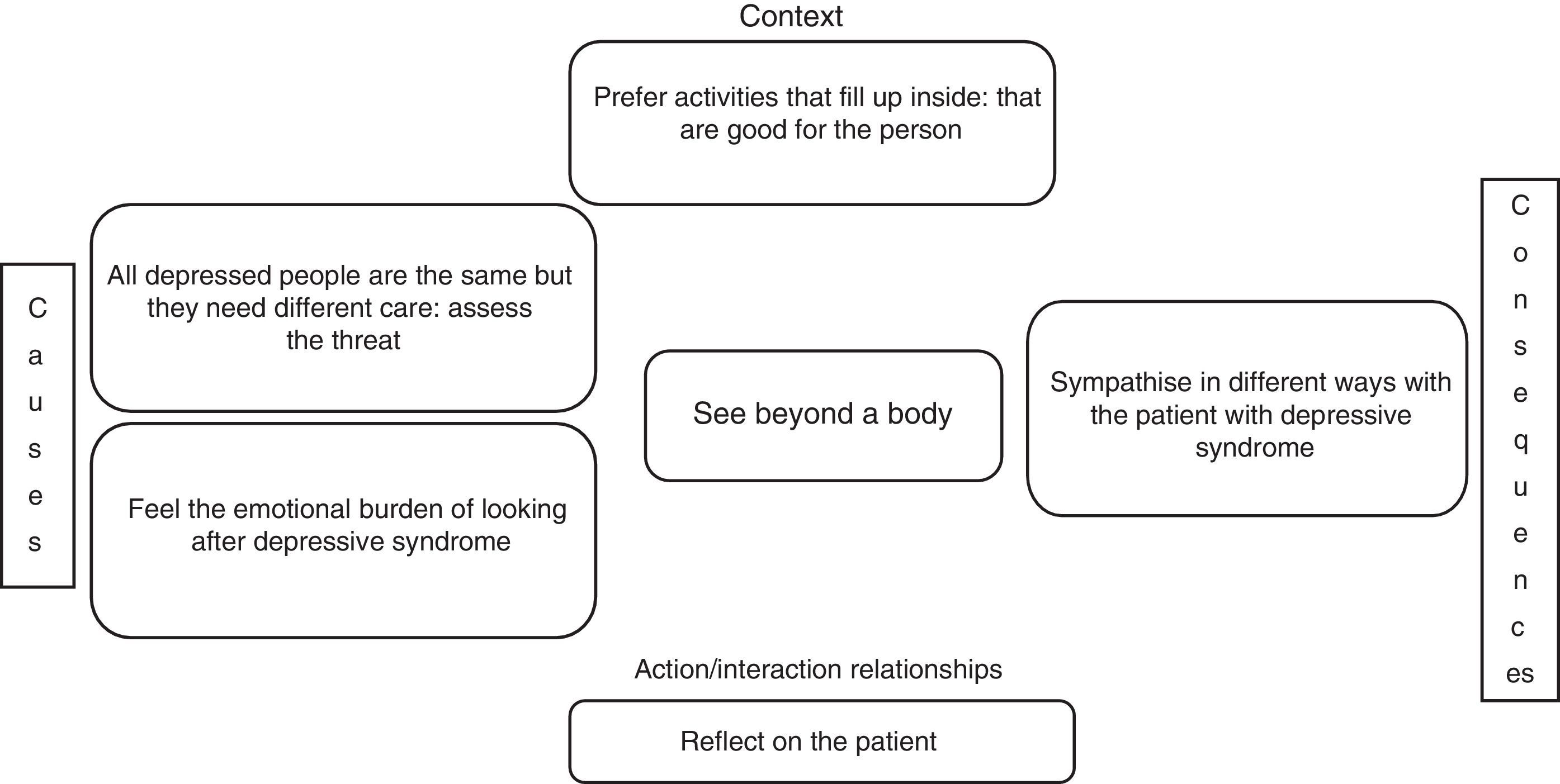

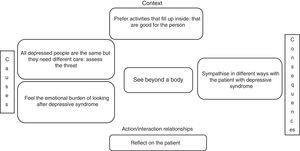

See beyond a bodyFrom the experiences of the interviewees, we found that in some, the concept they had of the person with depressive syndrome had evolved. They had moved on from considering them as part of a group of patients with certain symptoms that afflicted them and who required some substance to control the bothersome manifestations, to the fact that each of them is a “world” in themselves and they therefore require personalised care. However, the work experience that has generated these reflections has also led them to appreciate that the particular type of care these patients require is limited by the conditions that hold back the provision of medical care in the historical reality that is Colombia. And these conditions are dictated by the culture, the socio-political problems, the response capacity of the institution where they work and the type of patients they care for, “I have a very close relative with a mood disorder, and that has led me to be more sensitive to patients who have depressive symptoms and to think beyond the disease [...]; for example, where I did my rural training, there are patients who simply have to learn to live with the disease” (E4P5). “The emergency department is an absolutely tiny place. There are four trolleys, so if I filled all four trolleys, that was it! The rest of the patients were left outside waiting, and that was the catastrophe [...]. That was like the normal day to day [...]. Many patients came in with depression and with suicide attempts and not remission, no way! [...] Then, it was fluoxetine for everybody! For post-traumatic stress disorder, for schizophrenic patients too, it was fluoxetine for everything” (E12P5).

For the study participants, depressive syndrome is a compilation of bodily, behavioural and emotional feelings and manifestations that lead to the development or exacerbation of different organic diseases, including immune system disorders, pain-generating conditions, cardiovascular diseases and drug dependence. However, it also has a social impact, in terms of reducing the capacity to work and form social relationships, and even suicide. There is also a series of situations that tend to generate mental illnesses and others which, although they are not harmful in themselves, because of the way the subject interprets them, can cause an affective disorder often manifested in depressive syndrome.

“Right from the start, from the early days at university, looking at patients and hearing about diseases and listening to people talking about their illnesses, you already start to identify a certain association between organic disease and mental illness, including major depressive disorder in a large percentage” (E6P3).

This panorama leads these doctors to question their abilities to help, understand and really delve into the suffering of the patient and improve their situation, and to keep going in spite of everything, they pick up the lessons learned from their life experiences and put them at the service of the patient, who they see as more than just a body. “Sometimes you put yourself in the shoes of a patient, in that immense suffering that they are experiencing and that is so difficult to get out of, but that's what we are here for, to help them” (E17P11) (Fig. 1).

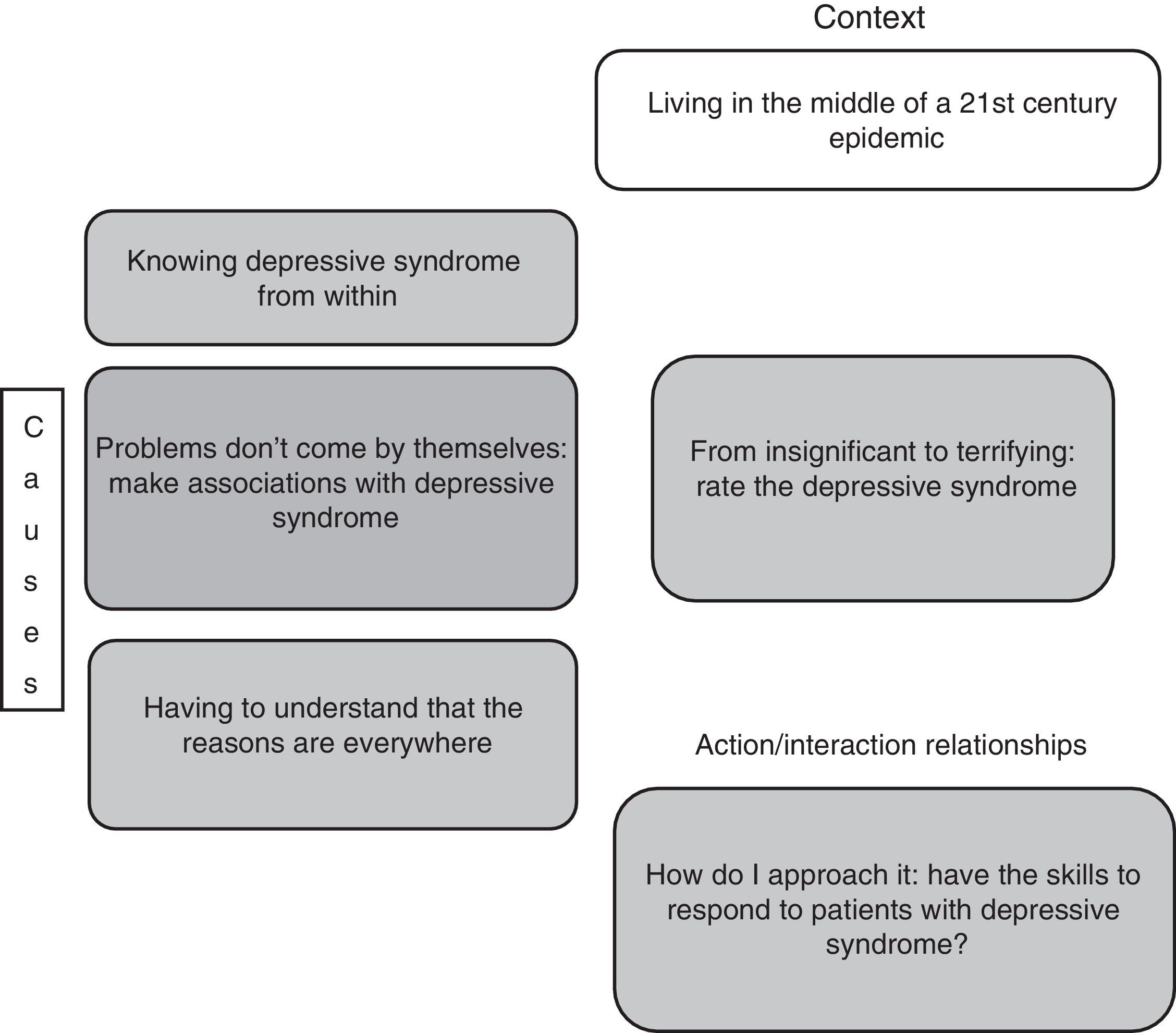

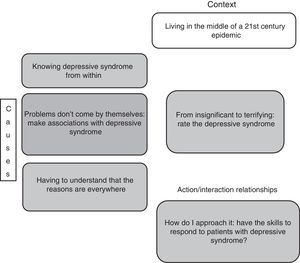

From insignificant to terrifying: rating of depressive syndromeThe interviewed doctors had theoretically studied depressive syndrome and had come across it in their professional practice. Others had even experienced it from other perspectives, whether as a relative, caregiver, friend or even as a patient.

“I suffered from depression, and that depression took me to very hard, very difficult places, with all the symptoms that depression has. I took antidepressants, but that was a stage in my own search that led me later to understand about the origin, how to do it, and now no, because the depression affecting my life has been gone for a while now... One of the things that seemed really good to me, after I was able get through that depressing period, it was like I was no longer speaking from scientific knowledge, but from my own experience, I was able to speak from within myself and teach people everything I had learned so that they could start looking at what they needed to do to also be able to come through it” (E2P3).

When these doctors’ desires to help come up against the limitations they have to deal with in their practice, they feel that their hands are tied and, as a result, give different ratings to depressive syndrome that range from insignificant to terrifying, based on their assessment of the experience they have had and of their capabilities to act in that scenario, seeking to fulfil their ideal of being a doctor; “Actually, your hands are tied a lot and you can try to offer your services, offer your knowledge, provide help without discriminating, but at the same time you end up becoming a bit indifferent and just try to do what you can with what you have” (E6P2) (Fig. 2).

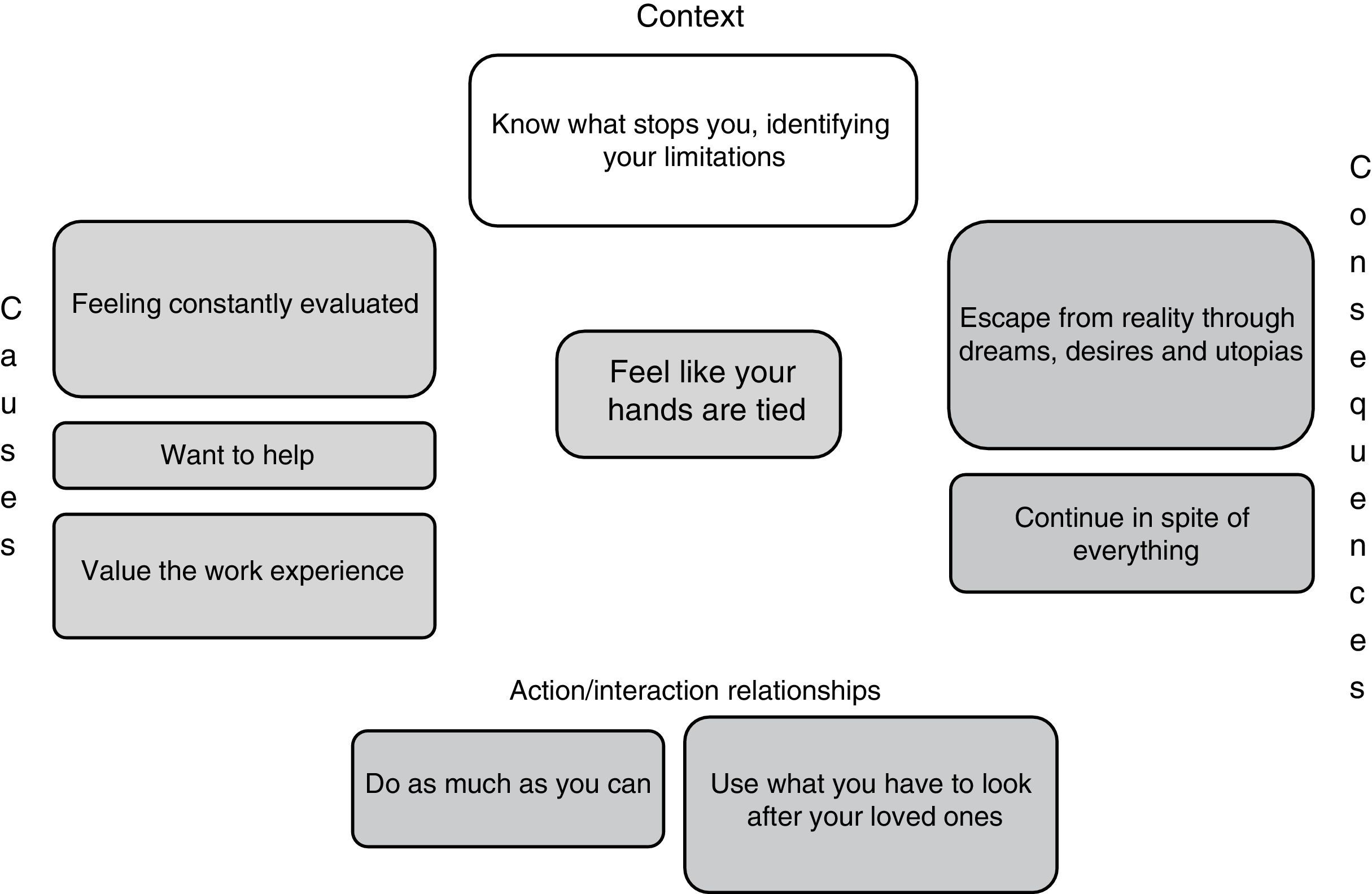

Feel like your hands are tiedThe limitations that the interviewees have had range from personal tastes and skills to socio-cultural conditions, including the quality of academic training and the conditions imposed by the health system. These limitations become apparent when comparing the reality they experience with the dreams and desires that drove them to become part of this profession. Not finding in practice what they had hoped for produced a range of different feelings that together defined the emotional burden they felt when having to deal with depressive syndrome, which was exacerbated by feeling they were constantly being evaluated, and included sadness, impotence, anguish, guilt and suffering; “It is very difficult because, as a human being, you feel affected too and wonder how this can be happening, that a person can end up feeling like that because of an illness, and there is very little to offer them in the way of a solution” (E13P3).

Moreover, in terms of what runs through these doctors’ minds when thinking about and dealing with depressive syndrome, they dream about having opportunities to care for the people who suffer from it and realise that they are being idealistic, but they also hope that one day it will become a reality and, in the meantime, they do as much as they can for their patients and use what they have available to care for their loved ones; “I don’t give up hope for psychiatric patients; what does fill me with despair is time. [...] But I do find it gratifying to think that I could diagnose a disease and that is suddenly going to help them for the rest of their life. Because, I know that if I try to help them with their depression, their whole life will change, everything; they’ll be able to improve their interpersonal relationships, their work, everything. So, that makes me feel like... more hopeful, like ‘Oh, I hope it works for them!’, ‘Let's hope the diagnosis is right and let's hope they follow the treatment’. Because, as you don’t see the results immediately, it's always like I hope they have listened to me” (E12P8) (Fig. 3).

Lastly, it was possible to relate all the points mentioned above through a conditional/consequential matrix and, with that, identify that the perception the doctors had in relation to depressive syndrome was determined by relationships at macro, meso and micro level of the phenomenon being studied (Fig. 4).

DiscussionSee the depressed patient past their illnessDoctors are professionals committed to medical science and the sick. Society places its trust in them because they are scientifically prepared to treat different diseases. Consequently, doctors manage scientific knowledge in all aspects: they have to apply it (providing care), investigate deeper (conducting research) and transmit it (teaching those who are still learning). Their commitment leads them through quality scientific training that enables them to contribute to the advancement of medical science and apply the best measures and principles of clinical practice.22

The Fundación Educación Médica [Medical Education Foundation] proposes that training in medicine should aim to ensure that doctors treat patients and not diseases, have a critical attitude, are communicators and empathetic, responsible individually and socially, make good decisions for the patient and for the system, are leaders of the healthcare team, competent, effective and safe, honest and trustworthy, committed to the patient and the organisation, and hold values of professionalism as a way of life.23 But for doctors to meet these expectations, they need to be educated in values.24 However, it is evident that this type of moral, ethical and personal competence requires a change of educational paradigm, for which we are poorly prepared.23

On that subject, the participants in this study mentioned that, for the clinical consultation to be of quality, it is necessary to have sufficient knowledge, sensitivity and skills to determine an accurate diagnosis and a suitable treatment, which does not depend exclusively on academics, the work environment or the length of clinical experience.

General practitioners see and treat depression from different perspectives based on their perception of the disorder. That perception — acquired from experiences with close family or friends, patients or even themselves, and their knowledge and recognition of the disorder, that its impact is not only organic, but also affective and social — in the end determines how they work in certain scenarios and points in their lives.

As Shultz25 points out, “Cognitive theory of personality focuses on how we know the environment and ourselves, how we perceive, evaluate, learn, think, make decisions and solve problems”. In this study, that makes sense when the interviewees describe personality characteristics as a crucial factor in their medical intervention, even in scenarios where we would expect behaviour to be mediated almost exclusively by the knowledge they acquired from their academic training.26

Assessment of disease from an empirical and an academic viewpointA doctor's medical training, however, is not only academic. The family and social environment in which a doctor has developed as a human being stimulates the construction of his or her personality.13 That is the case with the participants of this study, who highlighted that, for example, the religion they professed, the harmony of the place where they lived in their childhood and their parents’ attitude towards life equipped them with the virtues with which their character was being defined.13,27

One of the strongest elements that contribute to human formation and that sometimes can have a stronger pull than our will is the experience deriving from the events that have occurred in the family, social and work environments to which doctors have been exposed during the course of their lives.28 This has a great deal to do with the stigmatisation of patients based on previous experiences; what they observed in that relative, friend or even in themselves, means the doctor's response to disorders is conditioned by thinking about these previous events and the thoughts and feelings they provoked in him/her.11

In this regard, we find that, according to Aristotle in his work Nicomachean Ethics, “virtues arise in us neither by nature nor contrary to nature; but by our nature we can receive them and perfect them by habituation”. The doctor therefore has to possess a series of character qualities which are necessary for practicing medicine and intervene directly in the doctor-patient relationship: fidelity to patients’ trust, compassion, humility, practical wisdom, integrity, self-criticism, justice, strength, temperance, etc.22

In the case of this research study, the experiences reflected and transformed into narratives enabled us to analyse how the experiences of physicians as relatives, friends, students, professionals, observers, caregivers and patients influence the attitudes and behaviours they assume in different situations.24

The experiences that make up the personal baggage of the general practitioner essentially consist of all encounters that one way or another have aroused different emotions which, according to cognitive theories, are made up of beliefs, judgements and desires.29 Now, thanks to subjectivity,30 the experience of suffering derived from depressive syndrome allows each human being to give it a meaning,31 which may or may not be framed in some theory, as in the case of the participants in this study, who revealed a variety of different qualities of this condition, which ranged from the most empowering experience of human capabilities to the most abominable experience ever perceived.

If we look around in history, we see many ways to tackle suffering. We perceive the path of hedonistic evasion of suffering; the path of dullness in the face of suffering, until apathy is reached; the path of heroic struggle and overcoming suffering; the path of the repression of suffering and the illusionist denial of it; the path of justification, conceiving all suffering as punishment; lastly, the path of the Christian doctrine of suffering.32,33 All these paths need to be understood and studied by doctors, who will have to deal with the suffering of another on a daily basis and will have to steer their intervention based on that personal choice made by the patient, but also opening the doors to other options through scientific knowledge and empathy to achieve the best solution to the patient's problem.

According to this meaning, each doctor identified different emotions that preceded the actions he/she carried out when dealing with depressive syndrome. For example, those who feared depressive syndrome avoided dealing with it, referring the patient without even a minimal intervention; those who felt curiosity spent more time questioning the patient; those who were unconvinced possibly overlooked these types of signs and symptoms; and those who had learned to handle it with experience felt compassion for the situation the patient was experiencing and did what they could to help the patient, in spite of everything they had to deal with as a general practitioner; because, “You can live with depression. In fact, there are people who, thanks to their depression, discover that they are able to develop a particular moral depth from the experience, and this, in some way, alleviates the suffering to some extent”.34,35

Nevertheless, whatever the general practitioner's attitude and behaviour towards depressive syndrome, they were framed within the search for their own well-being, derived from the hedonic or eudaemonic perspective,36 which in the end turns the doctor-person encounter into a malleable and unfinished scenario that encourages its protagonists to reflect on each potentiality, limitation, meaning, attitude and behaviour that they have assumed when confronted with depressive syndrome, so that this experience joins their significant learning37 and serves as a starting point for a new process of action-reflection-action38 with which the doctor and his or her conception of the world are “transformed”.

One condition that generates experiences of varying emotional intensity in doctors, without any doubt, is depressive syndrome; it is almost certain that everyone has had contact with it, as this set of signs and symptoms is associated with a range of different sociohistorical, economic, psychological, physiological and pathological factors that permeate the doctor's environment which, at the same time, convert depressive syndrome into a 21st century epidemic. And with the current high prevalence of depressive syndrome and the problems it causes for the individual, one of the places a person with depression goes to seek help is the doctor's surgery.39 Frequently, patients with signs and symptoms of depression expect the doctor to alleviate the manifestations of a physiological, psychological and/or social condition they are suffering from, but that turns out to be depressive syndrome. General practitioners know about this condition from their academic training, but not always enough to meet the responsibility they are entrusted with to suspect, diagnose and appropriately treat the situations and disorders associated with depressive syndrome.40

However, thanks to the experience doctors gain in their personal and working lives,41 they have come to recognise that depressive aetiology is much broader than as described in the diagnostic guidelines,6 and management must therefore be holistic and multi-sectoral to be effective. These conditions go beyond physicians’ capabilities to resolve41–43 and they are often belittled by those who evaluate their work, among them the health service, the employer, the patient and their relatives, academia and society in general.44

Challenges imposed by the healthcare system for the care of patients with depressionDoctors and patients in Colombia interact in a context laden with restrictions, whether social, such as stigma; administrative, such as those imposed by the Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud; political, such as demands in terms of resource efficiency; geographical, such as those shown in the country's rural zone; and financial, like those experienced today by millions of Colombians. This situation threatens general practitioners; they perceive their hands to be tied and, as a result, they view depressive syndrome as a terrifying phenomenon that leads to multiple complications for the quality of life of the patient and the quality of their medical practice.44

As the participants in this study stated, the situation described becomes a source of suffering for doctors, especially if they see themselves as unable to cope and if they make negative comparisons with their original expectations when they decided to study medicine to help human beings reduce suffering.45 This then produces different sensations in the doctor, such as impotence, despair, sadness and anger,46,47 because they do not have the autonomy to sort out their own lives, as “the first need of the human soul”, because in the chaos they feel insecure and vulnerable.24,48

In the case of this study, the doctor, as caregiver, is called to help others to restore order in their lives and cushion the suffering derived from their experience with depressive syndrome, because “suffering is medicine's raison d’être”,49 while simultaneously sorting out their own lives to mitigate the suffering that derives from the act of living.50

Limitations of the studyAmong the limitations is the lack of studies focused on the perspective of the general practitioner, which makes it difficult to make comparisons between what we found in our research and the results of other studies. This prevented us from discussing some of the points dealt with in the study in more depth.

ConclusionsThe ability of general practitioners to diagnose and treat depression varies. That variability is associated with knowledge acquisition, skills, whether innate or acquired in practice, and the attitude with which general practitioners take on the job of caring, based on episodes in their own lives or previous experience with this type of disorder, and the impact or awareness those events have generated in them. It has been found that age and experience in practice do not lead to greater precision in diagnosis. However, general practitioners with vast knowledge and an appropriate approach to mental illness are more likely to effectively assess patients with psychiatric disorders. That is why we have to stress the importance of education in Columbia's medical schools where, in view of the huge significance of these disorders, the focus needs to be on proper communication and the correct approach to patients with depression who are directly affected by the deficiencies we have reported in this study.

Lastly, all of the above opens the way to a world of questions to be addressed through qualitative studies, in which topics such as education and the preparation given to general practitioners in the care of patients with mental illness can be addressed; and not only during their undergraduate studies, but also once they are working in health centres. It also presents an invitation to the different institutions that provide emergency and outpatient services to create care routes, optimise the consultation and improve the diagnosis and timely treatment of these conditions. All this with the aim of creating a health system which is more user-friendly for these people who feel so abandoned by society because of their mental illness (Fig. 5).

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

To the teachers Maria Vilma Restrepo Restrepo and Alejandra Gutiérrez Cárdenas, who, with their understanding and dedication, made this research possible.

Please cite this article as: Múnera Restrepo LM, Uribe Restrepo L, Yepes Delgado CE. Significado del síndrome depresivo para médicos generales en una región colombiana. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2018;47:21–31.