This study aimed to determine the prevalence of anxiety symptoms in a Colombian HCW sample during the COVID-19 pandemic.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was carried out by means of an online survey (May–June 2020). Respondents were HCWs in Colombia reached by a nonprobability sample. Zung's self-rating anxiety scale allowed the estimation of prevalence and classification of anxiety symptoms.

ResultsA total of 568 HCWs answered the questionnaire, 66.0% were women, the mean age was 38.6±11.4 years. 28.9% presented with anxiety symptoms, of whom 9.2% were moderate–severe. Characteristics such as living with relatives at higher risk of mortality from COVID-19 infection (OR: 1.90; 95% CI: 1.308–2.762), female sex (OR: 2.16; 95% CI: 1.422–3.277), and personal history of psychiatric illness (OR: 3.41; 95% CI: 2.08–5.57) were associated with higher levels of anxiety. Access to sufficient personal protective equipment (OR: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.318–0.903) and age >40 years (OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.358–0.789) were associated with lower anxiety levels.

ConclusionsAnxious symptoms are common in the population of HCWs faced with patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Different strategies are required to intervene with subgroups at risk of developing higher levels of anxiety during the pandemic.

Determinar la prevalencia de síntomas de ansiedad en una muestra de personal de salud (PDS) colombianos durante la pandemia por COVID-19.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio de corte transversal mediante una encuesta en línea (mayo a junio de 2020). Los encuestados fueron PDS en Colombia reclutados mediante una muestra no probabilística. La escala de autoevaluación de ansiedad de Zung permitió la estimación de la prevalencia y la clasificación de los síntomas de ansiedad.

ResultadosUn total de 568 PDS respondieron el cuestionario, el 66,0% fueron mujeres y la edad promedio fue de 38,6±11,4 años. El 28,9% presentaron síntomas de ansiedad, de los cuales el 9,2% fueron moderados-severos. Características como vivir con familiares con mayor riesgo de mortalidad por infección por COVID-19 (OR: 1,90; IC 95%: 1,308-2,762), sexo femenino (OR: 2,16; IC 95%: 1,422-3,277) y la presencia de historia personal de patología psiquiátrica (OR: 3,41; IC 95%: 2,08-5,57) se asociaron con mayores niveles de ansiedad. El acceso a elementos de protección personal suficientes (OR: 0,45; IC 95%: 0,318-0,903) y las edades >40 años (OR: 0,53; IC 95%: 0,358-0,789) se correlacionaron con menores niveles de ansiedad.

ConclusionesLos síntomas ansiosos son comunes en la población de PDS enfrentados al cuidado de pacientes durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Se requieren diferentes estrategias para intervenir los subgrupos en riesgo de desarrollar mayores niveles de ansiedad durante la pandemia.

Novel coronavirus infection described in December 2019 at Wuhan (COVID-19) started as a pneumonia of an unknown virus circumscribed to a region of China and then grew to a pandemic.1–3 Some studies carried out during previous epidemics have associated quarantine duration with higher incidence of negative emotions, affecting people's mental health and leading to an aftermath featuring characteristics such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), avoidant behavior, and anger.4–6 Similar studies have also showed that isolation times longer than 10 days had a positive correlation with more severe symptoms of PTSD than shorter isolation times.4,7,8

During the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese health care workers (HCWs) suffered an increase in the prevalence of anxiety symptoms. The symptoms (such as anxiety, sleep disorders, or exacerbations of previously diagnosed psychiatric pathologies) appear to be stronger among those HCWs in charge of the care of patients with a diagnosis or suspicion of COVID-19 infection.9–15

There are differences in perceived stress, anxiety levels, depression symptoms, and changes in mental health status among HCWs in several countries, with different results having been found among professions, specialties, gender, and other variables.16–18 Some governmental and scientific initiatives have exposed the need to raise awareness about this phenomenon and the possible management that it may entail.12,13,15

COVID-19 is probably the worst pandemic faced by Latin America in the last century.19 HCWs in this region have had several challenges related to this pandemic: lack of evidence-based knowledge about the new virus and changing protocols; constantly crowded consultation and emergency services facilities, which interfere with social distancing; the need for personal protective equipment (PPE); and rejection and attacks from the general population caused by the fear of being infective agents.20

Colombia first faced a national quarantine in March 2020, after the first COVID-19 case and related death were reported in the country. Previous pandemics have shown that quarantine produces in HCWs fear of contagion, concern about the safety of coworkers and peers in the health care field, loneliness, and demanding expectations, which could result in anger, anxiety, and stress related to the uncertainty of the event.20

In Colombia, previous studies have reported changes in perceived stress,21 sleep disorders,22 and psychological distress23 associated with COVID-19 infection in the general population. Currently there is a lack of evidence, limited to few studies assessing HCW population about perceived anxiety levels in Colombia during the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of anxiety symptoms in a sample of Colombian HCWs during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine.

MethodsStudy design and populationWe carried out a cross-sectional study through a self-administered online survey among a nonprobability sample of HCWs in Colombia. The survey remained online from May 20 to June 20, 2020.

Sample size calculation and sampling strategyWe calculated sample size with an expected frequency of 50%, an acceptable error rate of 5%, and a design effect of one for a population survey, with a resulting sample size of 384 participants.

Sampling was divided into two strategies. The first one was a virtual snowball method, by posting the survey in social media groups and contacts (WhatsApp and Telegram), asking respondents to answer and share the link with coworkers and colleagues. The other method was to send a predefined e-mail to renowned providers in charge of the direction or leadership of scientific communities (e.g., the Colombian Society of Anesthesiology and the Colombian Society of Plastic Surgery), asking for permission to share the posted link with their associate databases.

Estimation of prevalence and classification of anxietyTo assess anxiety among the survey respondents, we used the Zung self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) designed by William W.K. Zung in 197124 and posteriorly validated in Colombia by De La Ossa et al.25

The Zung SAS deploys a questionnaire of 20 items, each of which tests psychological or somatic anxiety-related symptoms using a 4-point ordinal scale based on frequency of presentation. Those items are presented in a positive or negative form (e.g., “I feel calm and can sit still easily” vs “I feel weak and get tired easily”). Respondents are asked to base their answers on experiences lived in a given period (usually the previous week, and with the present study, the previous month). The scores from the 20 items are then added together.24

According to the norms for the Zung SAS, raw scores (ranging from 20 to 80) are converted to an index score (ranging from 25 to 100).24 We used the original 1971 cutoff value of 50 points in the index score, considering it the value that produces fewer misdiagnoses compared with the cutoff value recommended later by Zung in 1980.24 The results with a positive value in the Zung index score (above 50 points) were reclassified according to the severity degree in three subgroups – mild, moderate, and severe anxiety – with cutoff points of 50–59, 60–69, and ≥70, correspondingly.26

Data analysisStatistical analysis of the results was done using the software SPSS v26.0. Continuous variables are shown with measures of central tendency and their dispersion. Categorical data are shown in frequencies and proportions. The chi-squared test was used to identify possible relations between categorical variables, as well as testing for the presence of anxiety symptoms (yes/no). Significance was established at p<0.05.

Ethical considerationsThis study was endorsed by the bioethics committee of the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira and was categorized as research “with minimal risk,” according to Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health, which guides research in Colombia. Likewise, the study adhered to generally accepted ethical principles, confidentiality, and the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients accepted the informed consent to participate in the study as well as to receive the results of their SAS.

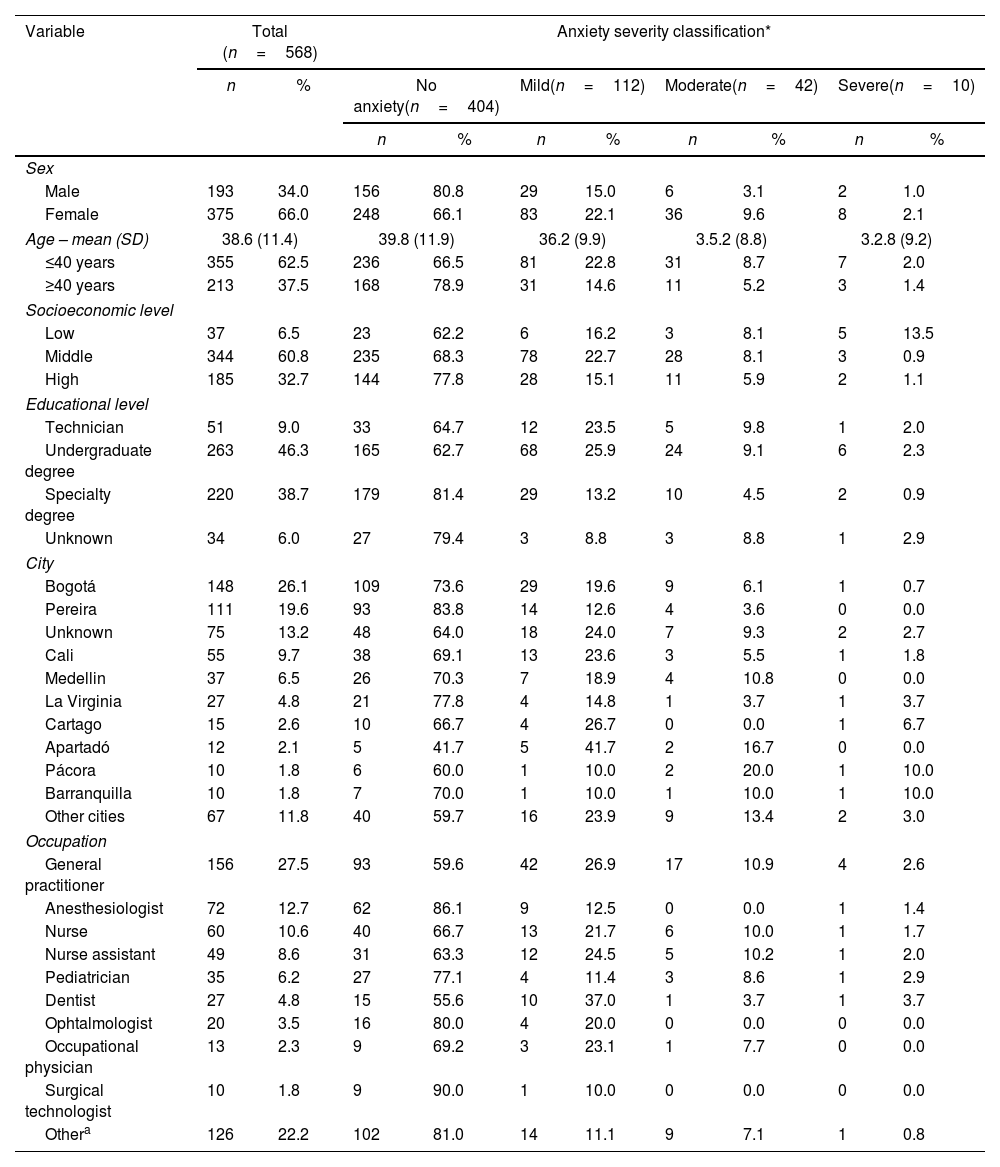

ResultsA total of 568 participants from 47 municipalities (23 of 32 departments) answered the survey during the study observation window. Sixty-six percent (n=375) were women. The mean age of the study population was 38.6±11.4 years (median 36 years; interquartile range [IQR]: 29–46 years). Socioeconomic level (SEL) was classified in six categories from 1 to 6, where 1 and 2 correspond to low SEL (6.6%, n=37), 3 and 4 to middle SEL (60.6%, n=344), and 5 and 6 to high (32.5%, n=185) (see Table 1).

Sociodemographic information of the respondents. Total sample and subgroups according to anxiety level.

| Variable | Total (n=568) | Anxiety severity classification* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | No anxiety(n=404) | Mild(n=112) | Moderate(n=42) | Severe(n=10) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 193 | 34.0 | 156 | 80.8 | 29 | 15.0 | 6 | 3.1 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Female | 375 | 66.0 | 248 | 66.1 | 83 | 22.1 | 36 | 9.6 | 8 | 2.1 |

| Age – mean (SD) | 38.6 (11.4) | 39.8 (11.9) | 36.2 (9.9) | 3.5.2 (8.8) | 3.2.8 (9.2) | |||||

| ≤40 years | 355 | 62.5 | 236 | 66.5 | 81 | 22.8 | 31 | 8.7 | 7 | 2.0 |

| ≥40 years | 213 | 37.5 | 168 | 78.9 | 31 | 14.6 | 11 | 5.2 | 3 | 1.4 |

| Socioeconomic level | ||||||||||

| Low | 37 | 6.5 | 23 | 62.2 | 6 | 16.2 | 3 | 8.1 | 5 | 13.5 |

| Middle | 344 | 60.8 | 235 | 68.3 | 78 | 22.7 | 28 | 8.1 | 3 | 0.9 |

| High | 185 | 32.7 | 144 | 77.8 | 28 | 15.1 | 11 | 5.9 | 2 | 1.1 |

| Educational level | ||||||||||

| Technician | 51 | 9.0 | 33 | 64.7 | 12 | 23.5 | 5 | 9.8 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Undergraduate degree | 263 | 46.3 | 165 | 62.7 | 68 | 25.9 | 24 | 9.1 | 6 | 2.3 |

| Specialty degree | 220 | 38.7 | 179 | 81.4 | 29 | 13.2 | 10 | 4.5 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Unknown | 34 | 6.0 | 27 | 79.4 | 3 | 8.8 | 3 | 8.8 | 1 | 2.9 |

| City | ||||||||||

| Bogotá | 148 | 26.1 | 109 | 73.6 | 29 | 19.6 | 9 | 6.1 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Pereira | 111 | 19.6 | 93 | 83.8 | 14 | 12.6 | 4 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unknown | 75 | 13.2 | 48 | 64.0 | 18 | 24.0 | 7 | 9.3 | 2 | 2.7 |

| Cali | 55 | 9.7 | 38 | 69.1 | 13 | 23.6 | 3 | 5.5 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Medellin | 37 | 6.5 | 26 | 70.3 | 7 | 18.9 | 4 | 10.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| La Virginia | 27 | 4.8 | 21 | 77.8 | 4 | 14.8 | 1 | 3.7 | 1 | 3.7 |

| Cartago | 15 | 2.6 | 10 | 66.7 | 4 | 26.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 6.7 |

| Apartadó | 12 | 2.1 | 5 | 41.7 | 5 | 41.7 | 2 | 16.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pácora | 10 | 1.8 | 6 | 60.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 20.0 | 1 | 10.0 |

| Barranquilla | 10 | 1.8 | 7 | 70.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 10.0 |

| Other cities | 67 | 11.8 | 40 | 59.7 | 16 | 23.9 | 9 | 13.4 | 2 | 3.0 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||

| General practitioner | 156 | 27.5 | 93 | 59.6 | 42 | 26.9 | 17 | 10.9 | 4 | 2.6 |

| Anesthesiologist | 72 | 12.7 | 62 | 86.1 | 9 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Nurse | 60 | 10.6 | 40 | 66.7 | 13 | 21.7 | 6 | 10.0 | 1 | 1.7 |

| Nurse assistant | 49 | 8.6 | 31 | 63.3 | 12 | 24.5 | 5 | 10.2 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Pediatrician | 35 | 6.2 | 27 | 77.1 | 4 | 11.4 | 3 | 8.6 | 1 | 2.9 |

| Dentist | 27 | 4.8 | 15 | 55.6 | 10 | 37.0 | 1 | 3.7 | 1 | 3.7 |

| Ophtalmologist | 20 | 3.5 | 16 | 80.0 | 4 | 20.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Occupational physician | 13 | 2.3 | 9 | 69.2 | 3 | 23.1 | 1 | 7.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Surgical technologist | 10 | 1.8 | 9 | 90.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Othera | 126 | 22.2 | 102 | 81.0 | 14 | 11.1 | 9 | 7.1 | 1 | 0.8 |

Other occupations include: epidemiologist, infectologist, gynecologist, family physician, internist, intensivist, orthopedist, bacteriologist, psychiatrist, dermatologist, general surgeon, respiratory therapist, otorhinolaryngologist, neurologist, neonatologist, neurosurgeon, gastroenterologist, radiology technician, pharmacy manager, pharmaceutical chemist, optometrist, nutritionist, rheumatologist, pneumologist, maxillofacial surgeon, gastrointestinal surgeon, cardiovascular surgeon. SD: standard deviation.

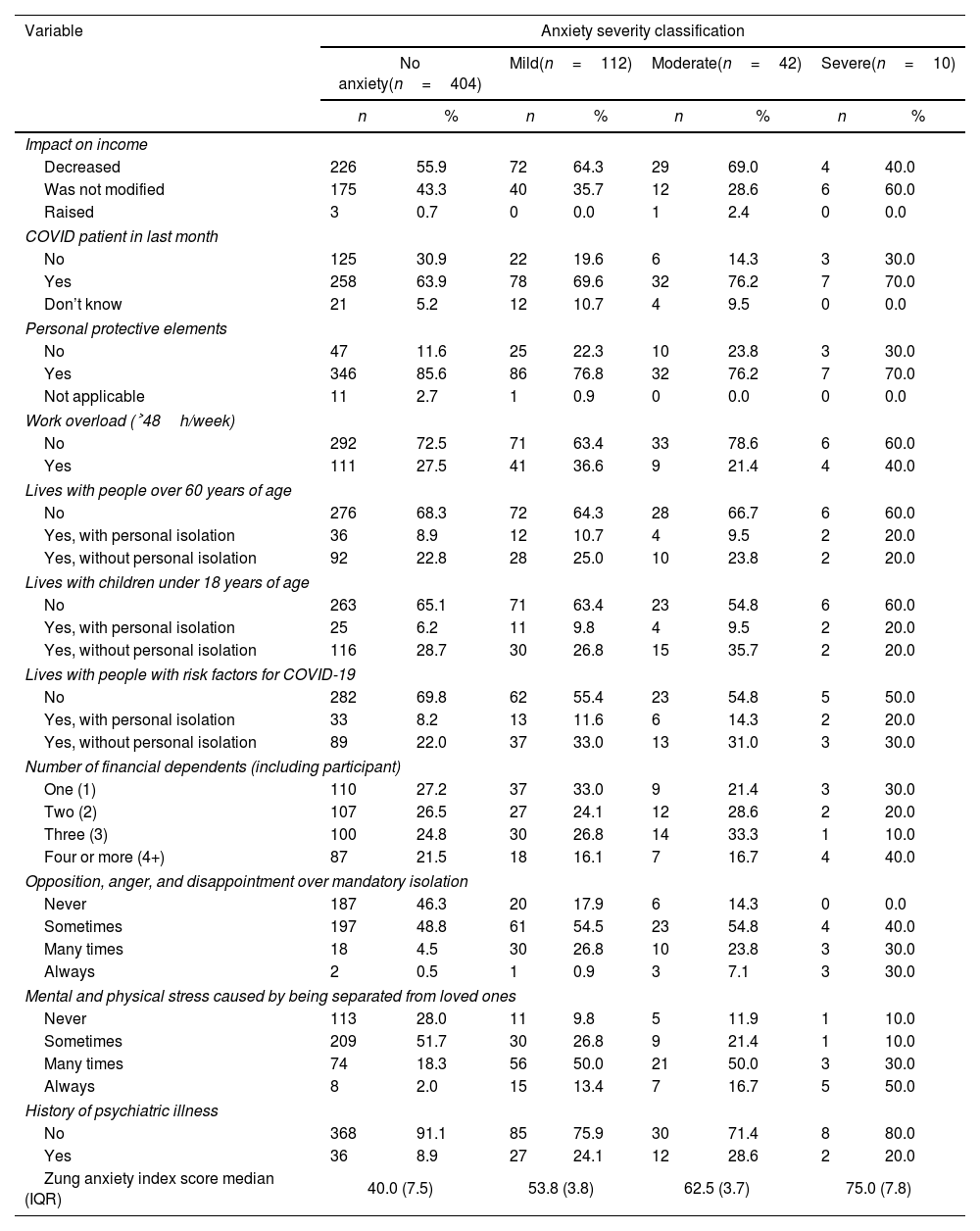

Most of the HCWs from the survey population used their private vehicles to go to work (n=434; 76.4%). The median of reported working time per week was 48h (IQR: 36–50h). Sixty-six percent (n=375) of the health professionals were involved in the care of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection patients, and 82.9% stated they had received personal protective equipment (PPE) (n=471) (see Table 2), a fact associated with a lower probability of having anxiety (p<0.001; OR: 0.45; 95% CI 0.318–0.903) or, in cases of presenting symptoms of anxiety, having a lower severity (p<0.018; OR: 0.54; 95% CI 0.318–0.903).

Miscellaneous factors explored in the respondents.

| Variable | Anxiety severity classification | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No anxiety(n=404) | Mild(n=112) | Moderate(n=42) | Severe(n=10) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Impact on income | ||||||||

| Decreased | 226 | 55.9 | 72 | 64.3 | 29 | 69.0 | 4 | 40.0 |

| Was not modified | 175 | 43.3 | 40 | 35.7 | 12 | 28.6 | 6 | 60.0 |

| Raised | 3 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| COVID patient in last month | ||||||||

| No | 125 | 30.9 | 22 | 19.6 | 6 | 14.3 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Yes | 258 | 63.9 | 78 | 69.6 | 32 | 76.2 | 7 | 70.0 |

| Don’t know | 21 | 5.2 | 12 | 10.7 | 4 | 9.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Personal protective elements | ||||||||

| No | 47 | 11.6 | 25 | 22.3 | 10 | 23.8 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Yes | 346 | 85.6 | 86 | 76.8 | 32 | 76.2 | 7 | 70.0 |

| Not applicable | 11 | 2.7 | 1 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Work overload (˃48h/week) | ||||||||

| No | 292 | 72.5 | 71 | 63.4 | 33 | 78.6 | 6 | 60.0 |

| Yes | 111 | 27.5 | 41 | 36.6 | 9 | 21.4 | 4 | 40.0 |

| Lives with people over 60 years of age | ||||||||

| No | 276 | 68.3 | 72 | 64.3 | 28 | 66.7 | 6 | 60.0 |

| Yes, with personal isolation | 36 | 8.9 | 12 | 10.7 | 4 | 9.5 | 2 | 20.0 |

| Yes, without personal isolation | 92 | 22.8 | 28 | 25.0 | 10 | 23.8 | 2 | 20.0 |

| Lives with children under 18 years of age | ||||||||

| No | 263 | 65.1 | 71 | 63.4 | 23 | 54.8 | 6 | 60.0 |

| Yes, with personal isolation | 25 | 6.2 | 11 | 9.8 | 4 | 9.5 | 2 | 20.0 |

| Yes, without personal isolation | 116 | 28.7 | 30 | 26.8 | 15 | 35.7 | 2 | 20.0 |

| Lives with people with risk factors for COVID-19 | ||||||||

| No | 282 | 69.8 | 62 | 55.4 | 23 | 54.8 | 5 | 50.0 |

| Yes, with personal isolation | 33 | 8.2 | 13 | 11.6 | 6 | 14.3 | 2 | 20.0 |

| Yes, without personal isolation | 89 | 22.0 | 37 | 33.0 | 13 | 31.0 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Number of financial dependents (including participant) | ||||||||

| One (1) | 110 | 27.2 | 37 | 33.0 | 9 | 21.4 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Two (2) | 107 | 26.5 | 27 | 24.1 | 12 | 28.6 | 2 | 20.0 |

| Three (3) | 100 | 24.8 | 30 | 26.8 | 14 | 33.3 | 1 | 10.0 |

| Four or more (4+) | 87 | 21.5 | 18 | 16.1 | 7 | 16.7 | 4 | 40.0 |

| Opposition, anger, and disappointment over mandatory isolation | ||||||||

| Never | 187 | 46.3 | 20 | 17.9 | 6 | 14.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sometimes | 197 | 48.8 | 61 | 54.5 | 23 | 54.8 | 4 | 40.0 |

| Many times | 18 | 4.5 | 30 | 26.8 | 10 | 23.8 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Always | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.9 | 3 | 7.1 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Mental and physical stress caused by being separated from loved ones | ||||||||

| Never | 113 | 28.0 | 11 | 9.8 | 5 | 11.9 | 1 | 10.0 |

| Sometimes | 209 | 51.7 | 30 | 26.8 | 9 | 21.4 | 1 | 10.0 |

| Many times | 74 | 18.3 | 56 | 50.0 | 21 | 50.0 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Always | 8 | 2.0 | 15 | 13.4 | 7 | 16.7 | 5 | 50.0 |

| History of psychiatric illness | ||||||||

| No | 368 | 91.1 | 85 | 75.9 | 30 | 71.4 | 8 | 80.0 |

| Yes | 36 | 8.9 | 27 | 24.1 | 12 | 28.6 | 2 | 20.0 |

| Zung anxiety index score median (IQR) | 40.0 (7.5) | 53.8 (3.8) | 62.5 (3.7) | 75.0 (7.8) | ||||

IQR: interquartile range.

Of the respondents, 159 (28.0%) did not report financial dependents, and 87 (21.5%) reported four or more financial dependents. When asked about people with whom they live, 186 (33.0%) reported living with people older than 60 years, 205 (36.0%) lived with people younger than 18 years, and 196 (35.0%) lived with people who presented a known risk factor of increased mortality from COVID-19 infection. For these categories of living arrangements, the participants isolated themselves from their relatives in 29.0%, 20.5%, and 27.6% of cases, respectively (see Table 2).

Zung anxiety scale and anxiety prevalenceThe median raw Zung anxiety scale score was 34.0 points (IQR: 30–41 points), and the median index score was 42.5 (IQR: 37.5–51.3 points). In Table 2 we describe the index score according to anxiety severity classification. Of the total population, 28.9% (95% CI 25.1–32.6%) presented with anxiety symptoms (n=164), and from those, 112 participants (19.7%) had mild, 42 (7.4%) moderate, and 10 (1.8%) severe anxiety. Women had a higher anxiety proportion than men (33.9% vs 19.2%, p<0.001, OR: 2.16; 95% CI: 1.422–3.277). Regarding anxiety severity classification according to sex, women had higher figures compared to men in mild (22.1% vs 15.0%), moderate (9.6% vs 3.1%), and severe (2.1% vs 1.0%) anxiety.

Those with a personal history of psychiatric illness had a greater probability of presenting anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic (p<0.001, OR: 3.41; 95% CI: 2.080–5.570). We also found that anxiety symptoms were more frequent in the younger group (≤40 years, 33.5%, n=119) compared with their older counterparts (>40 years, 21.1%, n=45, p<0.005, OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.358–0.789).

Those participants living with relatives with risk factors of increased mortality from COVID-19 infection had a higher proportion of anxiety compared with those who did not live with relatives with risk factors of increased mortality (37.8% vs 24.2%, p<0.001, OR: 1.90; 95% CI: 1.308–2.762). Although anxiety proportions in the groups of HCWs living with younger (<18 years) or older (>65 years) relatives were slightly higher than those who did not, there was not a statistically significant difference. Higher SEL was associated with a lower prevalence of anxiety (22.2% vs 32.3%, p<0.013, OR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.397–0.898).

DiscussionWith this analysis we were able to establish the prevalence of anxiety in a sample of Colombian HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic through an online survey. These findings can be helpful to HCWs, their employers, and health care authorities to create policies that mitigate risk.

Despite the fact that COVID-19-associated anxiety in HCWs presents a novel situation, some studies, mainly in the Chinese population, have found an anxiety prevalence ranging from 12.5% to 44.6%.9,14,27,28 Our results fit within the range of prevalence previously reported. Another study performed in Colombia (Medellín) found anxiety symptoms in 50.1% of the HCW included, on a similar date.29 The difference would be explained by the difference between the instruments used to assess anxiety. They used GAD-7, which includes cognitive and emotional anxiety symptoms characteristic of genal anxiety disorder (potentially more prevalent at that time for HCW), whereas SAS evaluates cognitive, emotional, autonomic, and physical anxiety symptoms in a broader spectrum.24

Many factors would influence the prevalence of anxiety in HCWs, explaining the differences among the studies. Our data were collected between May and June 2020, when Colombia was going through the third month of quarantine. Despite the fact that Colombia was reporting increasing new daily COVID-19 cases, this period represented an early stage of the outbreak. It is necessary to consider that the number of cases and the possibility of exposure to infection would affect the anxiety in HCWs, as has been proposed in other studies.30 Even though this was an early stage of the pandemic, knowledge about the strategies to face it was scarce, and uncertainty was high among the general population, including HCWs. These conditions, even in the absence of previous data about the prevalence of anxiety symptoms in HCWs in Colombia, could possibly be an independent cause of higher levels of anxiety.

As we did, some other studies have found a higher COVID-19-related anxiety prevalence in women working in health services.14,15,27 These sex-based differences are expected because the prevalence of anxiety disorders is higher in women potentially because of genetic, neurodevelopmental, environmental, and neurobiological factors.31 In this study, an increased anxiety prevalence was observed in HCWs with preexisting psychiatric diagnoses. This finding was also seen in other previous studies in HCWs.27 There is evidence in the general population showing that people with preexisting anxiety or mood-related disorders would exhibit increased COVID-19-related stress.32 There are some limitations in our study with respect to this issue, because we did not ask respondents to specify the mental health previous diagnosis, and this variable was based on self-report rather than clinical diagnostic evaluation.

A study performed on frontline medical staff members found that their sources of anxiety included their own and their family's safety. In our study, having family members with risk factors for increased COVID-19 mortality was associated with higher anxiety, a key factor because 38% of the population lived with people with these conditions. There is an under-recognized problem that would increase HCWs’ anxiety: fear, avoidance, and stigma. A study in the Canadian general population found that people had these negative feelings regarding HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic.33 This situation would reinforce the belief that HCWs are dangerous for their families.

HCWs who received PPE had lower anxiety prevalence. This finding has been described in other studies performed in similar populations,34 where researchers found a relationship between lack of PPE and increased COVID-19-related stress in HCWs.35 A worrying finding was the lack of PPE in almost 20% of HCWs in our study, something explored in Latin America, where this population lacks sufficient PPE and feels limited support from human resources and public officials.36

A systematic review assessed the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on mental health in the general population. The review, which included 19 studies in a qualitative synthesis of the literature, found among the included studies a correlation between younger age groups (≤40 years), lower educational level, poor self-rated health, high loneliness, female sex, divorced/widowed status, quarantine status, worry about being infected, history of mental health issues/medical problems, presence of chronic illness, living in urban areas, and specific physical symptoms.37

In China, the government and members of society typically compliment medical personnel for their dedication to fight COVID-19, trying to generate in HCWs feelings of being “honored and proud”.30 In Colombia, the government has defined an “economic recognition” with regard to HCWs dealing with COVID-19. Considering the influence of HCWs’ financial situation on the development of anxiety symptoms, interventions are needed to handle the anxiety burden in this specific population; such interventions would include better labor and self-care conditions.

Stuijfzand et al. discussed different alternatives to address the problem of mental health illnesses in HCWs during pandemics, including the COVID-19 pandemic. One consideration includes dividing the strategies according to the temporality of the outbreak during a pandemic's evolution. Stuijfzand et al. placed special emphasis on training of HCWs, planning and assignation of roles for staff and physical resources, and provisioning of sufficient PPE before the disease outbreak. Another strategy highlighted by these researchers was the importance of educational campaigns alerting HCWs about mental health and symptoms that warrant attention and professional help during disease outbreaks. Finally, after a disease outbreak, surveillance should be carried out to detect mental health and occupational problems over one year later.17

No specific interventions have been shown to mitigate COVID-19-related anxiety in HCWs. Some relevant aspects to improve HCW wellness include the following34: immediate and individualized access to mental health resources, short- and long-term individualized wellness and mental health interventions, individual and organizational strategies to optimize wellness of HCWs (nutrition, exercise, mindfulness, sleep quality), quality and accessible PPE, limitation in the infection risk (through strategies such as telehealth), reduced stigma on mental health symptoms, and development of new HCW community groups to reduce feelings of isolation.

The complexity of these interventions requires a commitment from governmental institutions: the possibility of the intervention being executed not by the government but by health personnel, health care provider institutions (IPS, from its acronym in Spanish), occupational risk management entities (ARL, from its acronym in Spanish), and health insurance companies (EPS, from its acronym in Spanish). In the absence of clear guidelines and a joint effort, implementation of programs aimed to improve mental health in HCWs will be difficult.

We used a nonrandomly distributed questionnaire to perform the research, causing selection bias in our study. Additionally, levels of anxiety might have modified the participation rate in our study, whether higher levels of anxiety raised or lowered participation rate is unknown. Our sample included a wide variety of HCWs (frontline personnel, medical staff, nurses, administrative staff), and this made it difficult to compare results between specific occupations, which reduced the statistical significance. Likewise, the distribution of our population does not represent the expected distribution of healthcare workers in Colombia, limiting the generalizability of our results. We used the SAS to assess the anxiety prevalence in our population. Even though the SAS is a well-known and validated scale, it is not specific for the evaluation of COVID-related anxiety (or anxiety from any stressor), and many troubles regarding its interpretation have been reported. The original SAS cut-off selected for this study allowed to exclude potential false positives, and to identify participants with more severe anxiety symptoms as positives, reducing the probability of misdiagnosis pursued in a research context. In a clinical context, the modified SAS cut-off could be most appropriate because the false negatives may represent not treated patients.26 We did not include other important variables such as the amount and quality of sleep in the population. Beyond the declared limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first published study to assess anxiety symptoms among HCWs in Colombia during the COVID-19 pandemic, which increases awareness about a problem that is usually disregarded.

ConclusionsFrom the results discussed above, it can be concluded that almost a third of the Colombian HCW population presented anxiety symptoms, and a positive relationship was found with some demographic variables like sex (greater prevalence for women), history of previous psychiatric illness, being a general practitioner, and cohabiting with people with risk factors of increased mortality from COVID-19 infection. Conversely, subgroups including anesthesiologists, those with access to PPE, older age groups (>40 years), and those at a higher socioeconomic level had fewer anxiety symptoms compared with the rest of the population.

We consider that the proper distribution of PPE and the creation of psychological work groups focused on populations like women and younger professionals could lead to a positive impact on anxiety prevalence among the HCW population.

There is a need to raise awareness about tired and stressed caregivers among HCWs. Timely identification of these characteristics will allow interventions, which would affect not only the health of HCWs but also that of those who are under their medical supervision.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.