Excoriation (skin picking) disorder is included in the DSM-5 in the obsessive compulsive and related disorders category. It is defined as the recurrent urge to touch, scratch, scrape, scrub, rub, squeeze, bite or dig in the skin, leading to skin lesions. It is a rare disorder (1.4–5.4% of the population) and occurs mainly in women.

Case reportthis article reports the case of a 31-year-old female patient, initially assessed by dermatology and orthopaedics for the presence of infected ulcerated lesions on her lower limbs, with other superficial lesions from scratching on her chest, arms, forearms, back and head. The patient also reported symptoms of anxiety, so was assessed by consultation-liaison psychiatry.

Discussionskin picking, normal behaviour in mammals, becomes pathological from a psychiatric point of view when it is repetitive and persistent, as in the case of excoriation disorder. In view of the reported relationship with the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cognitive behavioural therapy are recommended.

El trastorno por excoriación está incluido en el DSM - 5 dentro de la categoría de trastorno obsesivo compulsivo y trastornos relacionados. Se define como la urgencia de tocar, rascar, frotar, restregar, friccionar, apretar, morder o excavar la piel de forma recurrente hasta producirse lesiones cutáneas. Es un trastorno poco frecuente (1.4 - 5.4% de la población) y se presenta principalmente en mujeres.

Presentación de casoSe presenta el caso de una mujer de 31 años quien fue valorada por dermatología y ortopedia por presencia de lesiones ulceradas e infectadas en miembros inferiores, junto con otras lesiones superficiales por rascado en tórax, brazos, antebrazos, espalda y cabeza; además reportando síntomas ansiosos, razón por la cual es valorada por el servicio de Psiquiatría de enlace.

DiscusiónEl rascado cutáneo, conducta normal en los mamíferos, cobra valor patológico desde el punto de vista psiquiátrico al ser un acto repetitivo y persistente, como la conducta que se presenta en el trastorno por excoriación. Dada la relación descrita con el espectro obsesivo - compulsivo, se recomienda el uso de inhibidores selectivos de la recaptación de serotonina y la terapia cognitivo conductual.

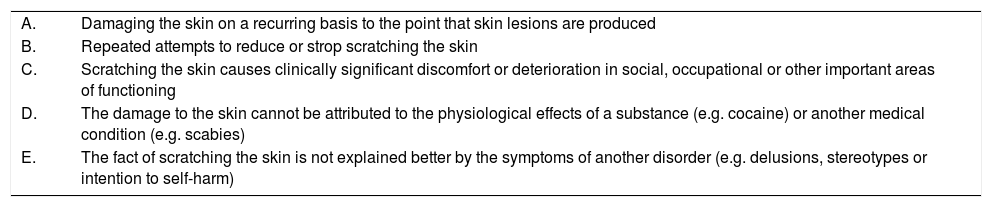

Skin picking disorder, also known as dermatillomania, neurotic excoriation, psychogenic excoriation or excoriated acne, was described for the first time in 1875 by Erasmus Wilson, under the name ‘skin picking’.1 It was initially included in the classification as an impulse control disorder, but in the face of the emergence of neurobiological, epidemiological and clinical evidence, the DSM-5 has recently included it within the category of obsessive compulsive disorder and related disorders. Table 1 lists the diagnostic criteria of this disorder, which is defined as the need or urgency to touch, scratch, rub, scrub, squeeze, bite or gouge the skin.2 It is estimated that it occurs in approximately 1.4–5.4% of the population, with a higher prevalence in women.3,4

Diagnostic criteria for skin picking disorder.

| A. | Damaging the skin on a recurring basis to the point that skin lesions are produced |

| B. | Repeated attempts to reduce or strop scratching the skin |

| C. | Scratching the skin causes clinically significant discomfort or deterioration in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning |

| D. | The damage to the skin cannot be attributed to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g. cocaine) or another medical condition (e.g. scabies) |

| E. | The fact of scratching the skin is not explained better by the symptoms of another disorder (e.g. delusions, stereotypes or intention to self-harm) |

Despite the fact that the prevalence in the population is low, skin picking disorder is likely to be under-reported, taking into account that it can be related to underlying diagnoses which determine the onset of scratching.

Case reportA 31-year-old woman went to the accident and emergency department for clinical symptoms which had started 18 months previously, with the appearance of ulcers on both lower limbs, which in the last 15 days had increased in size, had a bad odour, pain and discharge of purulent material. In the review of systems, she reported mixed insomnia, marked anxiety and hair loss. She did not have any other significant personal history. She was assessed by orthopaedics and dermatology, who found multiple exulcerations and rounded ulcers on the lower limbs, with suspected osteomyelitis and an immediate need to wash and surgical debridement, with subsequent biopsy (Fig. 1).

Furthermore, multiple superficial round lesions were documented, with serohaematic crusts with well-defined, non-infiltrated edges, and atrophic scars on the face, arms, back and glutes. The patient described them as self-inflicted and secondary to anxiety. An assessment by psychiatry was therefore requested; in this, affective symptoms of a depressive and anxious nature were reported, which had occurred daily since the age of 14 years, disproportionate for the stressors referred to as triggers and exacerbated in the face of arguments with her mother, with whom she revealed she had had a dysfunctional relationship since childhood. She also reported a history of consumption of alcohol and marijuana in adolescence, in addition to repetitive scratching behaviour of undetermined frequency by the patient, in order to control the affective symptoms described above, which have led to alterations in her social and relationship functioning (Fig. 2).

Given the presumptive diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder and skin picking disorder, pharmacological treatment was started with sertraline 50mg during the day (up to 100mg/day during hospitalisation), trazodone (50mg at night) and cognitive-behavioural psychotherapeutic intervention. The skin biopsy report was received, which revealed medium-sized vessel vasculitis consistent with polyarteritis nodosa. This only explained the lesions on the lower limbs, which were infected by the patient's actions. During her hospitalisation, she required multiple washes, debridements and covering with broad-spectrum antibiotics. The plastic surgery department considered that the patient was a candidate for covering with local or regional flaps on the lower limbs and the rheumatology department considered starting immunosuppression once the established antibiotic treatment was completed.

Furthermore, she adequately tolerated the established antidepressants, with significant improvement of anxiety, sleep pattern and scratching behaviours, as well as the lesions of her vascular disease.

DiscussionSkin scratching, a normal behaviour in mammals, can be considered pathological from a psychiatric point of view when it is a repetitive and persistent act.5 It tends to be a peripheral manifestation of a mood, anxiety, personality (obsessive or borderline) disorder, an intellectual disability or Tourette syndrome, and is a key symptom in obsessive compulsive disorder, dermatitis artefacta, body dysmorphic disorder and delusional parasitosis.5,6 For this reason, the nails and/or accessory tools such as tweezers and needles are often used,7 generating mild to severe tissue damage which can become complicated with infections to varying degrees (even becoming cellulitis) with permanent and disfiguring scars, and the consequent aesthetic and emotional damage.6,8,9 In prevalence studies carried out in the United States, it has been found that skin picking disorder is relatively common. In a study of 354 adult participants, 19 (5.4%) reported significant self-excoriation associated with malaise.10 In another study with 2513 telephone interviews, a prevalence of 1.4% was found.3

The age of onset of skin picking disorder varies significantly and can start early on in childhood or adolescence or be established in adult life in conjunction with another dermatological condition such as acne. The association of skin picking disorder and other psychiatric disorders is high; the most common comorbidities are depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, body dysmorphic disorder and trichotillomania.11

Individuals with skin picking disorder spend a considerable amount of time scratching, as well as dedicating additional time to inspecting lesions and compensatory camouflage behaviour (make-up, bandages, etc.).11,12 While biological and dermatological factors may cause the manifestation,2 the symptoms of the disorder continue due to a cycle of behavioural reinforcement characterised by a feeling of urgency and tension, followed by a feeling of relief and gratification.2 The face is one of the most common sites for the presentation of lesions, followed by the limbs. There is generally more than one site of scratching and excoriation. One study found an average of 4.5 sites with significant lesions.13

The nervous system and the skin have a common origin from the embryonic ectoderm. This is why, through lesions, the skin takes account of our emotional and mental state. In this light, psychiatric disease or dysfunctional psychosocial aspects can be recognised in 25–33% of dermatological patients.14 From a neurobiological perspective, common characteristics with trichotillomania have been found, such as higher density in the grey matter in the striatum, amygdala-hippocampal formation and in the convolution of the cingulum. Furthermore, disorganisation of the white matter tracts related to the interface of motor generation and suppression has also been found.15 Neuropsychological studies have found that individuals who suffer from skin picking disorder have cognitive disorders related to frontal functions such as deficit in the executive functions, impulsive components and tendency to inflexibility.16

With regard to pharmacological treatment, given the relationship described with obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders, the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) is recommended. Six open-label studies and one randomised study with placebo have been published (Simeon et al.17). The investigators found that one 10-week cycle of fluoxetine, with an average dose of 55mg/day, was associated with a significant reduction in two of the three outcome measurements. Other agents, including molecules with glutamatergic modulation, such as lamotrigine, have been studied with contradictory results.18 Some recent evidence sheds light on medicinal products with key anti-inflammatory and antioxidant action, such as N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) for the treatment of skin picking disorder and trichotillomania.18,19 In a recent randomised study of 66 participants with a diagnosis of skin picking disorder, a significant improvement was found with NAC compared to placebo. Of the 53 patients who completed the study, 15 of the 32 individuals who received N-acetyl cysteine (47%) had a significant objective improvement compared to four of the 21 individuals (19%) who received placebo (p=0.03), with an adequate tolerability profile.19

The most-studied non-pharmacological intervention is cognitive behavioural therapy. Habit reversal therapy or training (HRT) is designed to treat nervous habits and tics, in the circumstance that habits persist due to the response chain that is implemented in the face of limited awareness of the behaviour, the excessive practice of this behaviour and social tolerance towards them.20,21 The key elements of habit reversal therapy in skin picking disorder include self-monitoring, review of the appropriateness of the habit, training in a response which competes with the habit, social support and generalisation of the procedure.21,22 Teng et al. found that participants assigned randomly to HRT showed greater reduction of symptoms when finishing treatment and at follow-up after three months.20

ConclusionsDespite the prevalence and the impact of skin picking disorder, there are few studies from a clinical-therapeutic perspective. Most of the investigations are limited to trials with small samples and present methodological difficulties. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and psychopharmacological treatment with SSRIs are, for the time being, the most-used therapeutic modalities. There is great interest in the evaluation of molecules with key antiglutamatergic and antioxidant action, such as N-acetyl cysteine, with promising results.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Aranda M, Suárez GM, Henao AM, Oviedo GF. Trastorno de excoriación en una mujer con panarteritis nudosa. Reporte de caso. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2019;48:261–265.