Recovery in schizophrenia is a topic that generates not only major clinical attention but also a significant economic and social impact. Until seventy years ago, these patients remained held in psychiatric institutions or asylums, usually with no hope of reintegrating into the community. A narrative review of relevant literature was conducted in order to answer key questions regarding recovery in schizophrenia. Treatment objectives in schizophrenia have changed substantially: from expecting a modest control of psychotic symptoms to considering functional recovery as a possibility. Available evidence indicates that one in seven patients with schizophrenia will achieve functional recovery, which implies that remission of positive symptoms is not the ultimate goal of treatment but only a basis for better social and cognitive functioning that translates into better quality of life. This view until recently was not believed to be possible for this major mental disorder.

La recuperación funcional en la esquizofrenia es un tema que genera gran atención no solo clínica, sino también económica y social. Hasta hace pocas décadas, los pacientes esquizofrénicos permanecían recluidos en instituciones psiquiátricas o asilos, sin esperanza de reintegrarse a la comunidad. Se realizó una revisión narrativa de la literatura científica relevante, con el objetivo de responder a preguntas clave en relación con la recuperación en la esquizofrenia. Los objetivos terapéuticos en esquizofrenia han cambiado sustancialmente, de un tiempo en el que se esperaba un discreto control de los síntomas psicóticos al momento actual, cuando los esfuerzos terapéuticos se encaminan a que una proporción de pacientes alcancen la recuperación funcional. La evidencia disponible indica que 1 de cada 7 pacientes con esquizofrenia puede lograr la recuperación funcional, lo que implica la remisión sintomática no como meta final del tratamiento, sino como la base que permitirá alcanzar un mejor funcionamiento social y cognitivo que se traduce en mejor calidad de vida. Esta visión esperanzadora para este importante trastorno mental hasta hace poco no se creía posible.

Traditionally, schizophrenia has been defined as a severe, complex mental disorder, with a chronic and heterogeneous course.1 Eugen Bleuler, pioneer of psychiatry 100 years ago, published the book Dementia praecox oder die Gruppe der Schizophrenien [Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias],2 in which he described the chronic and incapacitating nature of schizophrenia. This bleak picture has lasted to this day, despite the extraordinary progress made in psychopharmacology and psychotherapies, but which has been insufficient to prevent schizophrenia being classed as one of the top 10 causes of disability in the world.3,4

Due to the severe functional deterioration associated with schizophrenia, the stigma that it generates, the psychosocial difficulties, the poor quality of life, the professional failure and family and social dependence, among other difficulties, it is clear that schizophrenia means more than delusions and hallucinations.5

Until now, the primary objective of treatment in schizophrenia has been focussed on reducing clinical symptoms (positive, negative and disorganised) and their consequences, such as symptomatic recurrence and hospitalisations.4 This approach, which is undoubtedly important, does not cover most of the daily problems faced by individuals with schizophrenia, and symptomatic improvement is not always accompanied by functional improvement. This is why only one in seven patients with symptomatic remission fulfil the functional recovery criteria.5,6

The information currently available on the aetiology, course and treatment of schizophrenia has piqued the interest of patients, families and healthcare professionals on the conceptualisation and meaning of functional recovery. Although the prognosis has been poor to date,6 another more promising vision has emerged which proposes that the course of schizophrenia is heterogeneous, which is why some patients could have a positive prognosis with adequate quality of life, autonomy, financial independence and satisfying interpersonal relationships.7

The objective of this study was to answer the following questions: ‘What does functional recovery in schizophrenia mean?’; ‘What proportion of patients achieve functional recovery?’; ‘What factors influence functional recovery?’; ‘What are the models of functional recovery in schizophrenia?’ and ‘What do patients themselves think about the topic?’

MethodsA narrative review of the relevant literature was carried out. The following search criteria were used: [recovery schizophrenia]; [rehabilitation schizophrenia] and [remediation schizophrenia]. The search was restricted to Spanish and English, and articles from which complete text was obtained, with no time limits. Articles were identified using PubMed, SciELO, Google Scholar and Cochrane. Meta-analyses, descriptive observational studies and systematic reviews which enabled the questions posed to be answered were selected.

ResultsA total of 413 references were identified with the specified search criteria, from which, after reading the title and the abstract, 60 which met the established criteria were selected. Of these, 59 were in English and only one was in Spanish. Three meta-analyses, three systematic reviews, 15 non-systematic reviews, nine descriptive studies, eight analytical studies, five experimental studies, three expert consensuses, one clinical practice guideline and one case report were included. Information obtained from six books and six patient comments were also included (Table 1).

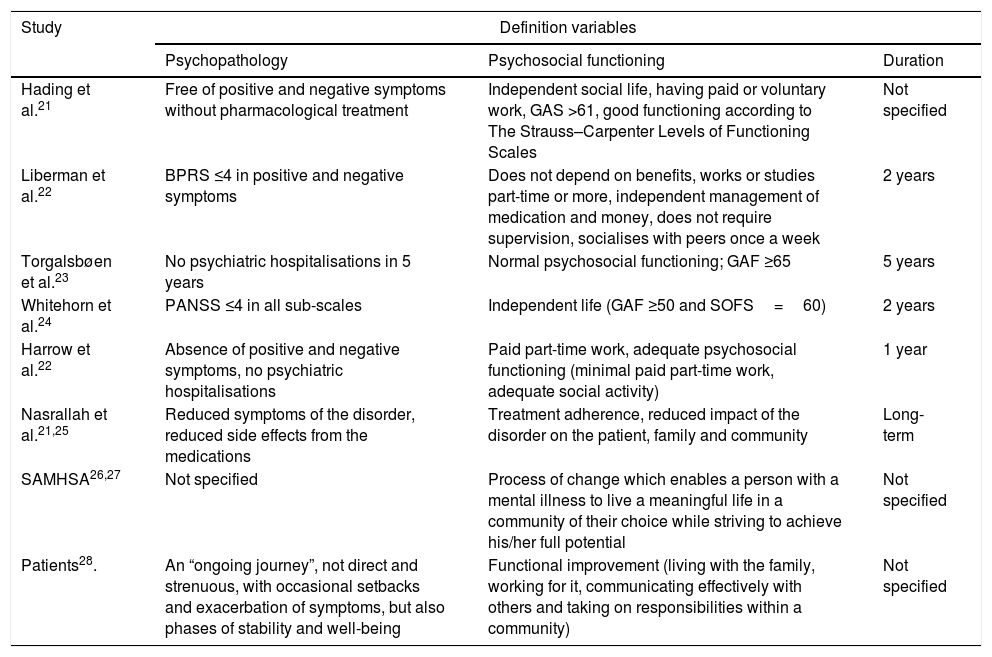

Conceptual definitions and recovery criteria in schizophrenia.

| Study | Definition variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychopathology | Psychosocial functioning | Duration | |

| Hading et al.21 | Free of positive and negative symptoms without pharmacological treatment | Independent social life, having paid or voluntary work, GAS >61, good functioning according to The Strauss–Carpenter Levels of Functioning Scales | Not specified |

| Liberman et al.22 | BPRS ≤4 in positive and negative symptoms | Does not depend on benefits, works or studies part-time or more, independent management of medication and money, does not require supervision, socialises with peers once a week | 2 years |

| Torgalsbøen et al.23 | No psychiatric hospitalisations in 5 years | Normal psychosocial functioning; GAF ≥65 | 5 years |

| Whitehorn et al.24 | PANSS ≤4 in all sub-scales | Independent life (GAF ≥50 and SOFS=60) | 2 years |

| Harrow et al.22 | Absence of positive and negative symptoms, no psychiatric hospitalisations | Paid part-time work, adequate psychosocial functioning (minimal paid part-time work, adequate social activity) | 1 year |

| Nasrallah et al.21,25 | Reduced symptoms of the disorder, reduced side effects from the medications | Treatment adherence, reduced impact of the disorder on the patient, family and community | Long-term |

| SAMHSA26,27 | Not specified | Process of change which enables a person with a mental illness to live a meaningful life in a community of their choice while striving to achieve his/her full potential | Not specified |

| Patients28. | An “ongoing journey”, not direct and strenuous, with occasional setbacks and exacerbation of symptoms, but also phases of stability and well-being | Functional improvement (living with the family, working for it, communicating effectively with others and taking on responsibilities within a community) | Not specified |

BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; GAS: Global Assessment Scale; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SAMHSA: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; SOFS: Social Occupational Functioning Scale.

Adapted from Liberman et al.7

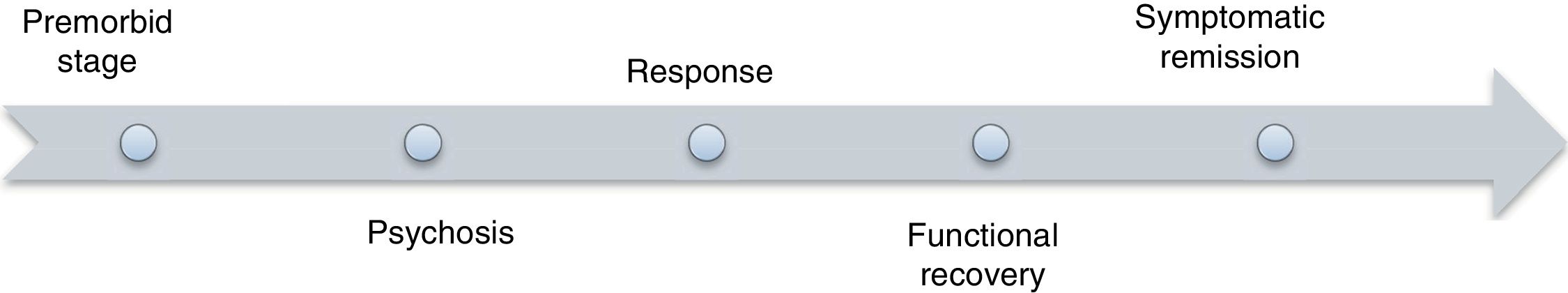

One of the difficulties when addressing this topic lies in the fact that the definitions are not universal.8,9 For researchers, recovery refers to a long period of remission of psychotic symptoms, while for clinicians it means an improved general functioning, and for patients the term is associated with the ability to return to being the person they were before and functioning in daily activities without needing to take medication.7,8 There is some consensus in that functional recovery in schizophrenia is the final stage of a process which starts with the response to pharmacological treatment and that ultimately, in some cases, will enable the remission of symptoms if factors such as adherence to treatment, improved cognitive functioning and others are presented (Fig. 1).

Definition of symptomatic remissionIn 2003, the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group,10 in view of the scientific evidence that the long-term course of the disorder was not as unfavourable as believed, defined symptomatic remission in schizophrenia as “the state in which the patient shows improvement in signs and symptoms, to such an extent that they do not interfere significantly in their behaviour and they are below the diagnostic threshold”.

Evaluation of symptomatic remissionSeveral proposals have been put forward to evaluate symptomatic remission. These include instruments such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),11 the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),12 the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)13 and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS),13 and a formula which makes it possible to calculate the percentage symptom reduction (initial SANS−final SANS×100/final SANS−30).14,15 The percentages of remission according to the above formula vary between 20% and 88% depending on the study.16–18 It has been said that this approach is positive because it does not require the total absence of symptoms, although six months of reduced symptoms are requested.19

What does functional recovery in schizophrenia mean?The therapeutic objectives in the treatment of schizophrenia have changed gradually, from a discreet expectation with regard to self-care, control of self-aggressive and hetero-aggressive behaviour, to the most effective control of psychotic symptoms.19 The model of “functional recovery” has recently been proposed, which requires symptomatic remission not as a final treatment goal, but instead as a base which makes it possible to achieve improved social and cognitive functioning and an improved quality of life, although not absolutely, since it is assumed that schizophrenia is a chronic condition for which there is no “cure”, but rather improvement.8,20

It is better to perceive functional recovery in schizophrenia as a multidimensional construct, instead of an objective condition or a specific level of functioning. Multiple authors have addressed the topic from various perspectives. However, the definition and criteria proposed by Liberman et al.7 are currently the most widely accepted and most widely used for clinical and research purposes (Fig. 1).

Definition of recovery according to patientsPatients’ definitions have emerged from the civil rights movement and political–social changes in relation to mental disorders.8 According to one schizophrenic patient, “a lot can be achieved when we detach ourselves from what we were and we determine what we are now, and what we can become”. This gives an idea of the existential transformation that these patients suffer when experiencing schizophrenia, of which little has been said up to now.29–31

Some patients, for example, feel that they are better people for having experienced the recovery from their illness, even when they admit that in the social role it transformed into a condition of minor importance.32 Another aspect that they highlight is that the path towards recovery is a “fight”, often marked by relapses and continuous adjustments.8 Of course, the perspectives of patients are diverse, and for some treatment is worse than the illness and is what “blocks the recovery”, which leads to them abandoning it and seeing this as a sign of their “progress”.33–36 A systematic review which included 25 articles from several European, American and Asian countries reported that patients perceived recovery not as a symptom-free state, but as understanding the illness and learning to live with the consequences of it.28

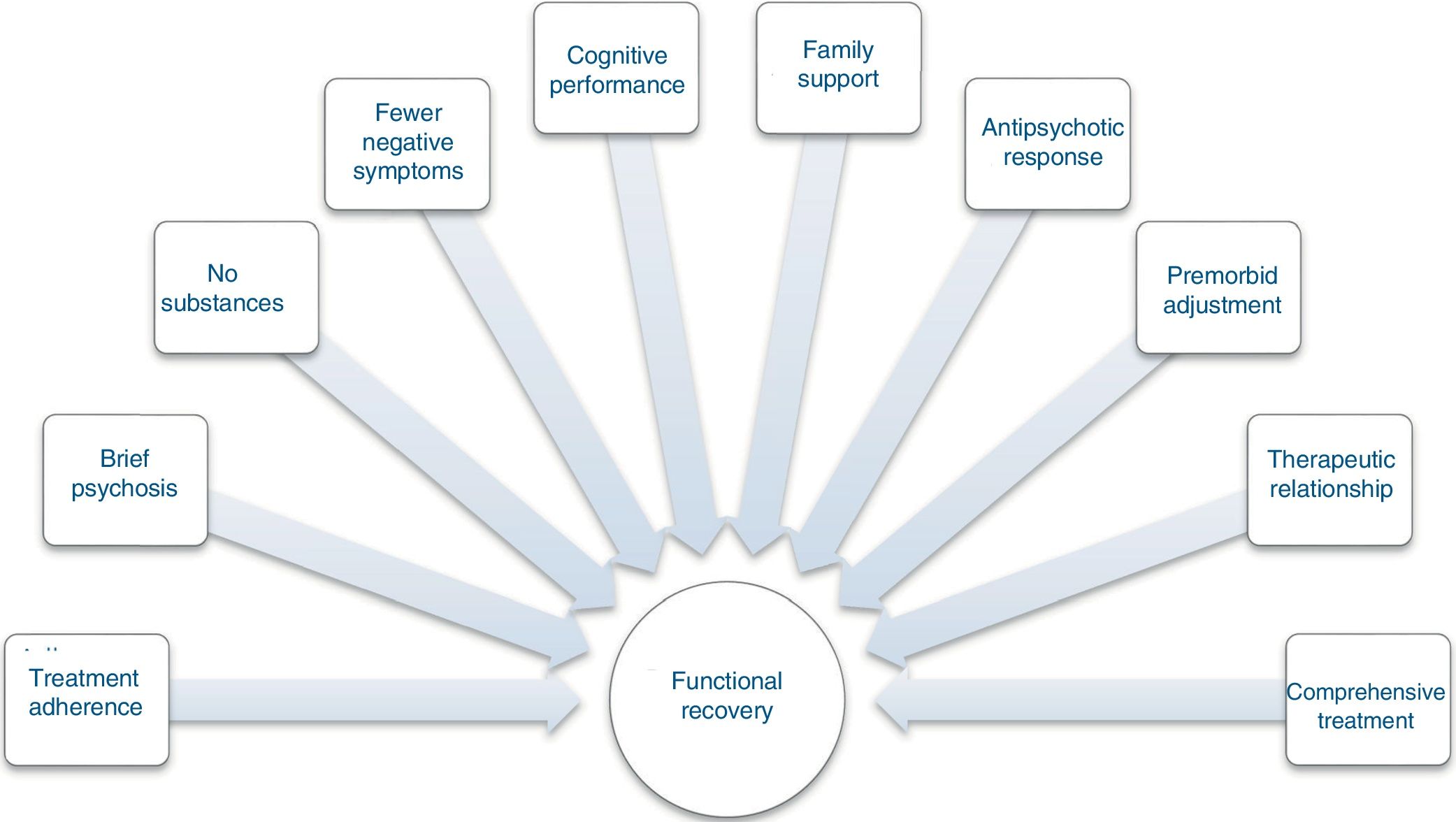

Factors that influence functional recoveryThere are multiple factors associated with functional recovery in schizophrenia. Functional recovery depends on multiple characteristics of the patient, as well as external factors and the treatment, which makes it complicated to predict who will achieve it22 (Fig. 2).

Factors related to functional recovery in schizophrenia. Adapted from Liberman et al.7

Liberman et al.7 identified 10 factors associated with functional recovery (Fig. 2). In a meta-analysis, Jääskeläinen et al.37 identified that studies carried out in economically poorer countries reported higher proportions of social and functional recovery than more economically developed countries (19% versus 13%). As protective factors they identified resilience, less stigma and improved self-image.37

One of the most important expectations for patients, families and clinicians is the deterioration in quality of life, understood as individual perception in relation to goals and expectations in the context of own values and culture. Some researchers have identified psychotic symptoms as factors which deteriorate patients’ quality of life,37–39 while a study carried out by Xiang et al.,39 which included 200 schizophrenic patients, found that depressive symptoms were the only independent factor associated with worse quality of life.

Factors which have been associated with a lower likelihood of recovery are depressive symptoms, the adverse effects of medication,6,40,41 less cerebral asymmetry,42 early onset of the condition, a lower educational level, impulsivity, family history of schizophrenia43 and anxiety.37

Factors that influence recovery according to patientsIt has been found that the negative perception of patients themselves on their recovery process acts as a risk factor for recovery, while those who do not consider themselves ill, due to lack of introspection, cannot be considered in functional remission.4 Denial of the disorder itself can be encouraged by therapeutic nihilism and stigma of the disorder.41

The following were identified as factors that promote recovery according to the patients themselves: (a) having a doctor who maintains an optimistic view of recovery, who motivates them to change and to take part actively in the treatment41; (b) who informs and educates them actively; (c) who takes into account their needs and desires44; (d) who teaches them strategies to resolve daily life problems44,45; and (e) who teaches them how to use their time effectively.46

Recovery modelsUntil the end of the 1960s, the Rehabilitation Model for schizophrenia was used in the United States. From this point on, a social movement emerged with which the patients sought to empower themselves from their condition process by forming organisations and associations with the aim of fighting for the dignity and freedom of those who are mentally ill. These individuals started to document their own experiences, in addition to giving their opinions and perceptions with regard to functional recovery.47

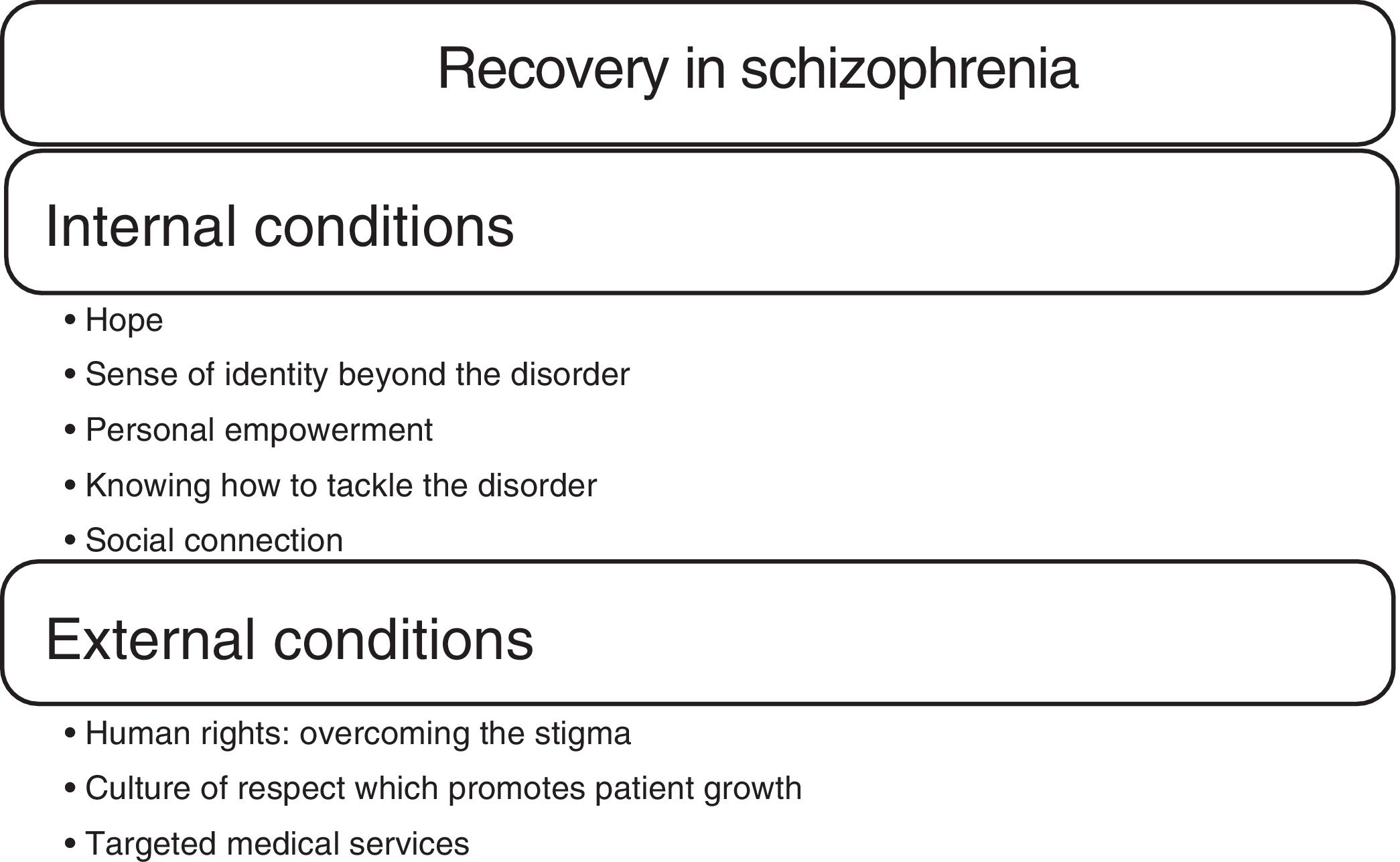

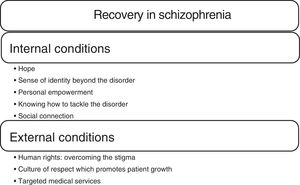

More recently, Jacobson et al.48 have understood the recovery model in schizophrenia based on internal and external conditions (Fig. 3). Andresen, for her part, describes the meanings of recovery through a continuum with three identifiable points: the medical model; the rehabilitation model and the empowerment model.32 The first assumes that the mental disorder is a physical condition and recovery is the return to the previous state of general functioning, which implies cure.29 The second argues that, although the disorder is incurable, the person can improve without returning to the level of functioning that he or she had before the onset of the disorder49; this model claims that the person learns to live well despite the limitations of his or her disability.32 Finally, the empowerment model argues that the mental disorder does not have a biological basis, but that it is a sign of severe emotional suffering in light of stress factors that the patient can overcome from understanding, optimism and autonomy, as well as recovering and resuming their previous social function.50

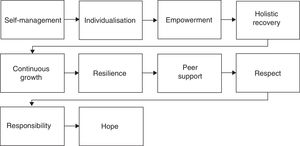

Phases of the recovery model32Patients go through different phases in the recovery process, which have been described in the following manner:

- •

Procrastination: characterised by the denial of symptoms, confusion and despair.

- •

Awareness: the person considers that recovery is possible.

- •

The person understands that he or she is more than just a sick person.

- •

Preparation: the recovery work starts, the person recognises his/her strengths and weaknesses, learns about the mental disorder and the services available, acquires skills that make the recovery easier and participates in groups.

- •

Reconstruction: the person works to build a positive identity, achieve goals, make him or herself responsible for the management of the disorder and assume control of his or her own life.

- •

Growth: the person is not completely symptom-free, but knows how to manage the disorder and achieve well-being.

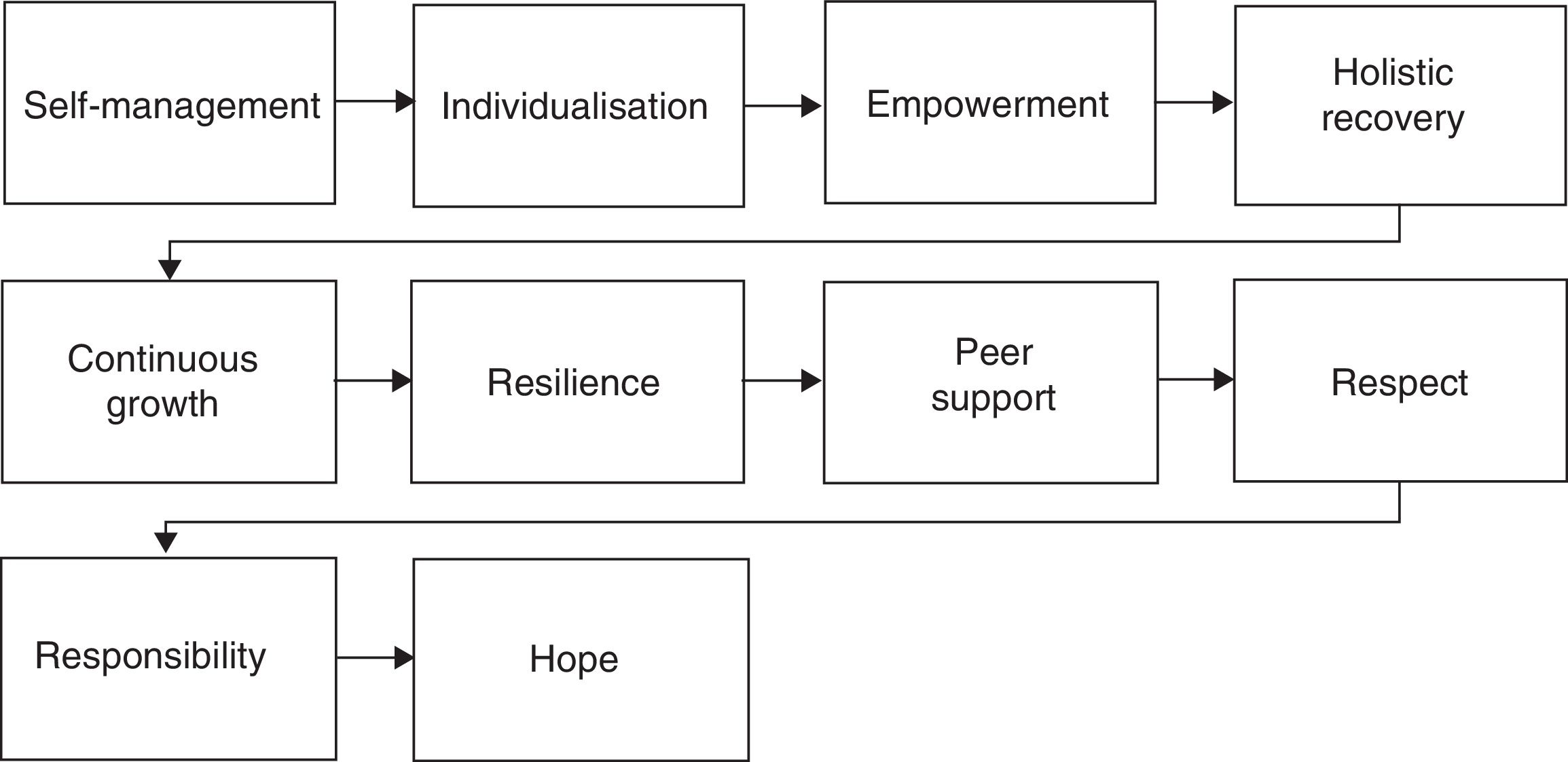

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines the 10 components that make it possible to achieve functional recovery in schizophrenia; hope is the key component, as it is the catalyser of the recovery process, and is a protective factor against the vulnerability of stress and stigma26,27 (Fig. 4).

What proportion of patients with schizophrenia recover?The schizophrenia treatment guideline of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) establishes that the treatment response time can be between one and two years to go from an acute phase with florid symptoms to a stabilisation phase, and subsequently to a recovery phase.51

Starting with the Vermont Longitudinal Study, today there are more than 20 recent clinical trials focused on the long-term outcome of schizophrenia, with different methodologies and definitions, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions. However, between 20% and 70% of individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia seem to have good outcomes, with a substantial reduction of symptoms, good quality of life and functionality during long periods. The modal percentage of patients with good outcomes is 50%.8,21,52

A meta-analysis carried out by Finnish and Australian researchers reported that the rate of annual recovery from schizophrenia is 1.4%, which indicates that of every 100 people with schizophrenia per year, one or two will fulfil functional recovery criteria, and approximately 14% will fulfil them after 10 years.53

In a study that used the criteria proposed by Lieberman et al. and included 118 young people followed-up for five years, 47.2% (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 36.0–58.4%) of the subjects achieved symptomatic remission, and 25.5% (95% CI, 16.1–34.7%) had adequate social functioning after two or more years. Only 13.7% (95% CI, 6.4–20.9%) fulfilled the symptomatic and functional recovery criteria after two or more years. After three years, 9.7% continued to fulfil the criteria; 12.3% did so after four years, and 13.7% did so after five years.41,42 A meta-analysis that included 50 articles found that 13.5% (95% CI, 8.1–20.0%) of patients achieved functional recovery.53

Taking the above into account, if the operational criteria are met, recovery from an episode is equivalent to recovery from schizophrenia.41 A need that persists is to develop psychometric scales to evaluate objectively social participation, empowerment and hope, among other aspects.8,54

Therapeutic approaches in schizophreniaThe treatments validated for schizophrenia are varied. They include treatment with psychotropic drugs, which have been the cornerstone, programmes against substance abuse, psychoeducation, social skills training, therapy and family psychoeducation, community treatment and employment with support. These last four psychosocial treatments are supported by scientific evidence that suggests they offer a greater chance for psychosocial functioning to improve and schizophrenia relapses to diminish.41,55

Some of these non-pharmacological therapies supported by scientific evidence are presented below.

Social skillsThis training aims to improve social functioning and achieve an independent social life. It is based on the fact that behaviour is subject to change and that patients can learn with observation and direct instruction or role play.56

Cognitive behavioural therapyCognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) addresses symptoms that can improve social functioning and quality of life. Initially, CBT in psychosis was aimed at positive symptoms, but recently greater attention has been paid to applying this model to negative symptoms.57

Hogarty's cognitive enhancement therapy includes cognitive training and group therapy. A randomised trial with 81 patients found improvement in neurocognition, social cognition and social adaptation.55

Cognitive adaptation trainingCognitive adaptation training (CAT) proposed by Velligan et al.58 is a compensatory cognitive rehabilitation programme that uses support in the home and the environment (e.g. alarms, signals and checklists) to facilitate independence in the home environment. CAT has been used to improve adherence to medication, hygiene, self-care, space management, free time and social activities.

Errorless learningErrorless learning proposed by Kern et al.59 is based on carrying out a certain task without errors and the subsequent learning of complex tasks. It promotes the training of stimulus-response connections, where the fundamental principle is the elimination of errors during learning (cornerstone) and the automation of the response.

Social cognitive trainingSocial cognition has been defined as “the ability to construct representations of the relationships between oneself and others and to use these representations flexibly to guide social behaviour”. Social cognitive training is a multifaceted concept that tries to make schizophrenic patients perceive, interpret and generate more assertive responses with regard to intentions, willingness and emotions of the people they interact with on a daily basis.60

In schizophrenic patients, impairments have been reported in four areas: (a) perception of affection, due to inability to “know how to read” facial expressions of emotions; (b) social perception, this is the ability to judge from non-verbal cues or gestures of others; (c) attributional style, which refers to how individuals explain the causes of positive and negative events in their lives, and (d) theory of mind, the ability to understand how others have mental states that differ from their own and from this to make correct inferences on the content of those mental states.55

Training of affect recognitionTraining of affect recognition (TAR) by Wolwer et al.59 proposes improving recognition of facial emotions. A study which included 77 patients with the objective of comparing TAR, neurocognitive rehabilitation and routine treatment showed improvement in the perception of facial expressions when TAR was implemented, but there was no improvement in verbal learning or in long-term memory.

DiscussionFunctional recovery in schizophrenia is a recent concept for an old problem if it is considered that, until 60 years ago, schizophrenic patients were sometimes detained for life in asylums or mental institutions. The development of antipsychotic drugs and other psychotropic drugs offered schizophrenic patients the possibility of “deinstitutionalising” and returning to society to face new challenges derived from the “social reintegration” process.9

Although from a clinical point of view the initial focus of treatment in schizophrenia consisted of keeping the patient free of psychotic symptoms, relapses and hospitalisations, from the functional recovery perspective and the viewpoint of the expectations of patients, families and society in general, the objective was far from being fulfilled. It was necessary to include other success criteria, such as achieving a productive life, recovering autonomy and achieving a life of well-being.61

The scientific evidence currently available has made it possible to verify the need to incorporate psychosocial treatments into treatment strategies for schizophrenic patients by means of integrated programmes of pharmacological treatment and psychosocial rehabilitation. Some countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Australia and New Zealand, among others, have included the concept of functional recovery in mental health policies for patients with schizophrenia.62

Further research into the topic is required to establish which are the best pharmacological and psychosocial strategies to offer schizophrenic patients the best opportunity to achieve functional recovery.

ConclusionsFunctional recovery in schizophrenia involves not only remission of symptoms, but achieving greater autonomy to manage one's own life. Until recently, this promising view for this significant mental disorder was not thought possible. The available evidence indicates that one in every seven patients with schizophrenia can achieve functional recovery if adequate pharmacological and psychosocial treatment is available.

More studies with improved methodology and which make it possible to understand how a greater number of patients can be helped to achieve functional recovery in schizophrenia are required.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Silva MA, Restrepo D. Recuperación funcional en la esquizofrenia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2019;48:252–260.