The analysis of songs as discursive practices contributes to the understanding of the social representations of mental disorders in specific populations, as has been suggested in the literature. The aim of this article is to expand the knowledge about the depictions of madness (a broader but less delimited concept than psychosis) in the popular music focussing on emerging themes and their cross relations within the discourses of the madness in Spanish punk.

Material and methodsQualitative research method. After the review of 3653 songs (1981–2010) insights from the Thematic Analysis of all the 163 identified lyrics of Spanish punk songs with the terms ‘mad,’ ‘madness’ or other related words are provided.

Results and discussionAfter a thorough discussion of the main themes, the expression of subculture’s identity became evident. Its otherness was recognizable on the exaltation of madness as loss of control or unpredictability as well as its links with crime, substance abuse or ideological opposition, among others.

ConclusionsThe idea of dangerousness linked to ‘madness’ emerges as a final pathway of different identified themes, suggesting a potential explanation for the general population attitudes towards the theme of madness.

La importancia de las canciones como prácticas discursivas para el acceso a las descripciones de los trastornos mentales en poblaciones específicas ha sido sugerida previamente. El presente estudio busca ampliar la literatura existente en torno a las ideas sobre la locura en la música popular, superando la mera descripción de usos y sentidos, para enfocarnos en los temas emergentes y sus interrelaciones en los discursos sobre la locura presentes en el punk español.

Material y métodosSe recurrió al análisis temático como estrategia de investigación cualitativa. Un análisis sistemático en 6 fases fue implementado. Después de revisar los contenidos presentes en una muestra de 3.653 canciones punk españolas (1981–2010), se realizó el análisis temático de las 163 obras en las que fue posible identificar los términos «loco», «locura» u otros relacionados.

Resultados y discusiónLos principales códigos temáticos identificados son abordados en detalle, destacando aspectos de afirmación identitaria propios de la subcultura expresados mediante la exaltación de la locura como descontrol, desenfreno e impredecibilidad, la asociación con la criminalidad y el consumo de tóxicos, o la oposición ideológica, entre otros.

ConclusionesLa relación locura-peligrosidad es una vía final común identificada entre las propuestas que emergen de las canciones analizadas, sugiriendo una explicación posible a las actitudes de la población general hacia « la locura», un concepto más amplio y pobremente definido que el de «psicosis».

“For sure we’re mad as goats and music doesn’t matter to us”. “We are mad as goats”. Urgente, 1983.

Psychiatry is a medical discipline closely related to historical and conceptual developments at the social level, since the beliefs, norms and values of a culture influence perceptions about what is considered a mental disorder or not.1 Thus, ideas and representations of mental disorders and their treatment vary according to cultural guidelines.2,3 These bidirectional relationships between culture and medicine are relevant in psychiatry due to the nature of its endeavour.

Apart from the descriptions of mental disorders in the press and other media, the influence of literature, television and cinema have contributed to a stigmatised perception of mental illness and psychiatric practice.4–11

Stigma is a broad concept that, from a social perspective, includes labelling, the generation of stereotypes and their subsequent separation, as well as the loss of status and discrimination of stigmatised subjects.12 Its manifestations range from social stigma to self-stigma and encompass people who suffer from mental disorders, as well as the professionals who care for them, treatments and institutions.4–11,13

Media analyses suggest that descriptions of people with mental disorders are characterised by an emphasis on violence and criminality, unpredictability and social incompetence,4,5,14,15 which furthers their stigmatisation.

In our opinion, these points are relevant in daily practice, since these and other representations emerge in patients and their relatives in different phases of the clinical encounter. In turn, stigma and discrimination have been identified as one of the main barriers to seeking psychiatric treatment.6,16

In this context, understanding popular ideas about mental disorders and identifying the social impact of the circulation of such ideas are particularly relevant. It has been suggested that artistic manifestations could operate as “cultural fossils”, allowing us to track social representations of psychiatric practice and mental disorders in a specific population and a specific period.17 The analysis of songs as discursive practices and their contribution to this field of study has previously been defended.18,19

Despite the aforementioned points and the interest in “madness” at an artistic level, representations of mental disorders in music have been poorly studied in the medical field, the focus being on the analysis of musical content referring to disorders due to substance use.17 Thus, the works related to the descriptions of “madness” are anecdotal.17 Among them, the descriptions in opera are the most recurrent (in particular, the “scenes of madness”)2,20,21 and, to a lesser extent, the relationships between rock and madness.17

The study of specific subcultures and constrained time periods is important, since - far from being restricted to topics of local interest - it allows us to reduce heterogeneity and enables comparison with other works of a similar nature. In this sense, comparing and contrasting the findings in Spanish punk music and the results of the study of Brazilian popular music18 has allowed the suggestion that some meanings of madness could be universal in popular culture (namely, the ideas of madness as “pathology”, “loss of control” and “opposition to reason”).22

Spanish punk has characteristics that make studying it attractive. On the one hand, it is a reference genre for other scenes and styles22 and, on the other, its evolution can be traced through its exponents from the early 1980s to the present day. This aspect is of interest if we look at the historical period in which the trajectory of Spanish punk is inscribed, the origins of which are close to the advent of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, from the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-III in 1979) and which evolved in parallel with Psychiatric Reform in Spain (1985) and the subsequent development of healthcare models.

We hypothesise that - in the context of punk as an attitude of questioning authority and social order - its proximity to socially marginalised groups may open a point of encounter with mental disorders and, in particular, with psychotic disorders as a paradigm of “what does not fit into a society of normal people”. On the other hand, substance use (which can operate as an identifying factor of the subculture, as a way of accessing altered mental states, as an expression of alienation, self-marginalisation or a search for evasion, or simply as a maladaptive mechanism of individuation and independence) can influence the appearance of comorbid psychiatric conditions. Along the same lines, there are descriptions of biographical data that link rock and punk with psychiatry and mental disorders.19,23

Finally, an advantage of studying this subculture resides in access to explicit, easily identifiable content that brings us closer to everyday expressions related to our object of study, which reduces interpretation bias and facilitates agreement between independent coders.

As a preliminary approach to the study of the social representations of psychosis, the present work seeks to delve into the study of references to “madness” (a cultural concept, broader than that of “psychosis”). The objective is to go beyond the mere description of uses and meanings, to focus on emerging themes and their interrelationships in the discourses of madness present in the analysed subculture.

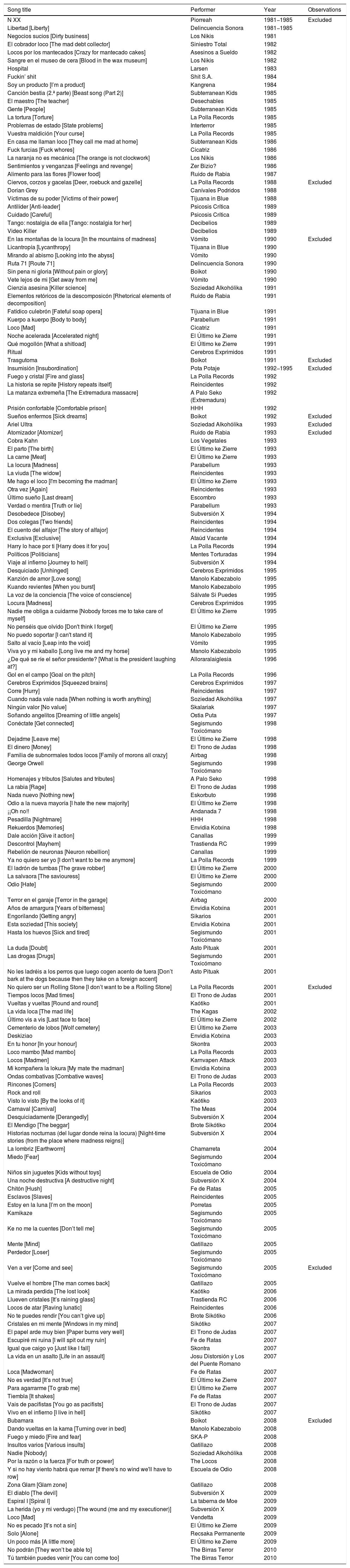

Material and methodsThe search focused on Spanish punk bands with albums released in the period 1981−2010. The list of musical groups contained in the Dictionary of Punk and Hardcore (Spain and Latin America),24 as well as other source documents25–28 and the review of web forums and specialised portals,29–31 guided the discography search, in order to obtain a broad and inclusive sample of material.

A list was made of the musical groups most frequently referred to in the different source documents,24–31 which included 177 bands. Among the songs contained in their discographies, only those sung in Spanish were included. Instrumental songs, musicalised poems, and versions of songs by other groups were excluded from the analysis. Repeated songs were considered only once (first version).

Of a total of 5647 songs that met the inclusion criteria, a sample of 3653 songs that did not include psychotic disorders as the main theme was randomly selected. The sample size was calculated considering a heterogeneity of 50%, for a confidence level of 95% and a minimum margin of error (1%). The lyrics included were reviewed by two independent coders in search of references to the terms: “loco” [crazy, mad], “locura” [madness], the different forms of the verb “enloquecer” [go crazy], “demente” [insane], “demencia” [insanity], as well as other related words of colloquial use. This phase led to the identification of 174 songs, of which 11 were excluded because of specific mentions of madness, without a clarifying context that made them susceptible to analysis (Appendix 1).

We opted for the analysis of songs whose main themes were not linked to psychosis, taking into account the cultural load of the term “madness” and our objective of broadening the vision of the meanings assigned to it at the popular level, as an initial exploratory phase, before undertaking the study of the more concrete field of the social representations of psychoses.

Although each song was considered as the main context unit, they could contain one or more themes related to madness. The concept of “reference” was used to indicate each one of the mentions to the different themes identified. This explains why the total number of references is higher than the number of songs. Repetitions of the same sentence (e.g. in the chorus) were not added to the total frequency of references, and were considered only once for each song.

For the analysis of the material, the qualitative strategy of thematic analysis (TA) was used. TA is a systematic method for the identification, organisation and understanding of the patterns of meaning present in a data set.32 It was considered appropriate for our objective considering its accessibility, flexibility, systematisation32 and the consequent possibility of replication, in addition to its greater analytical depth with respect to other qualitative strategies, such as, for example, content analysis.

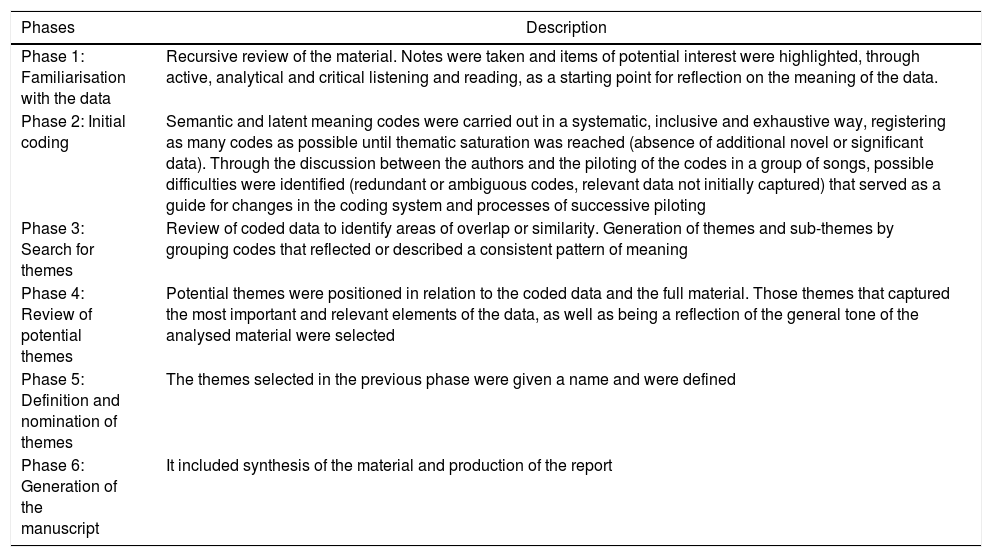

The TA structure proposed by Braun and Clarke32,33 was used for a systematic analysis in six phases (Table 1). The participation of two independent coders was aimed at optimising internal consistency. Discrepancies were resolved without difficulty through discussion between the authors.

Phases of the thematic analysis implemented in 163 punk songs (Spain, 1981–2010).

| Phases | Description |

|---|---|

| Phase 1: Familiarisation with the data | Recursive review of the material. Notes were taken and items of potential interest were highlighted, through active, analytical and critical listening and reading, as a starting point for reflection on the meaning of the data. |

| Phase 2: Initial coding | Semantic and latent meaning codes were carried out in a systematic, inclusive and exhaustive way, registering as many codes as possible until thematic saturation was reached (absence of additional novel or significant data). Through the discussion between the authors and the piloting of the codes in a group of songs, possible difficulties were identified (redundant or ambiguous codes, relevant data not initially captured) that served as a guide for changes in the coding system and processes of successive piloting |

| Phase 3: Search for themes | Review of coded data to identify areas of overlap or similarity. Generation of themes and sub-themes by grouping codes that reflected or described a consistent pattern of meaning |

| Phase 4: Review of potential themes | Potential themes were positioned in relation to the coded data and the full material. Those themes that captured the most important and relevant elements of the data, as well as being a reflection of the general tone of the analysed material were selected |

| Phase 5: Definition and nomination of themes | The themes selected in the previous phase were given a name and were defined |

| Phase 6: Generation of the manuscript | It included synthesis of the material and production of the report |

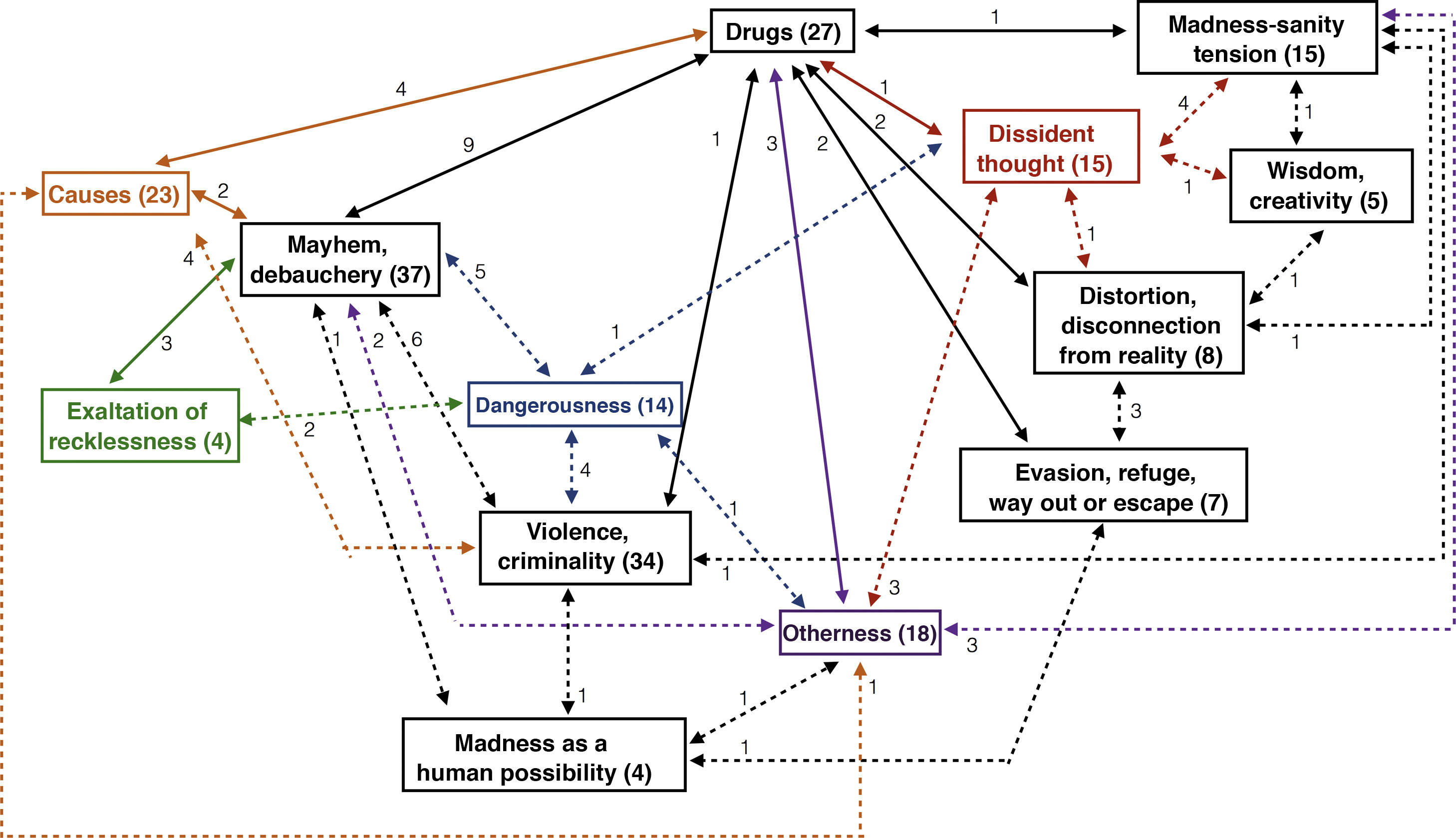

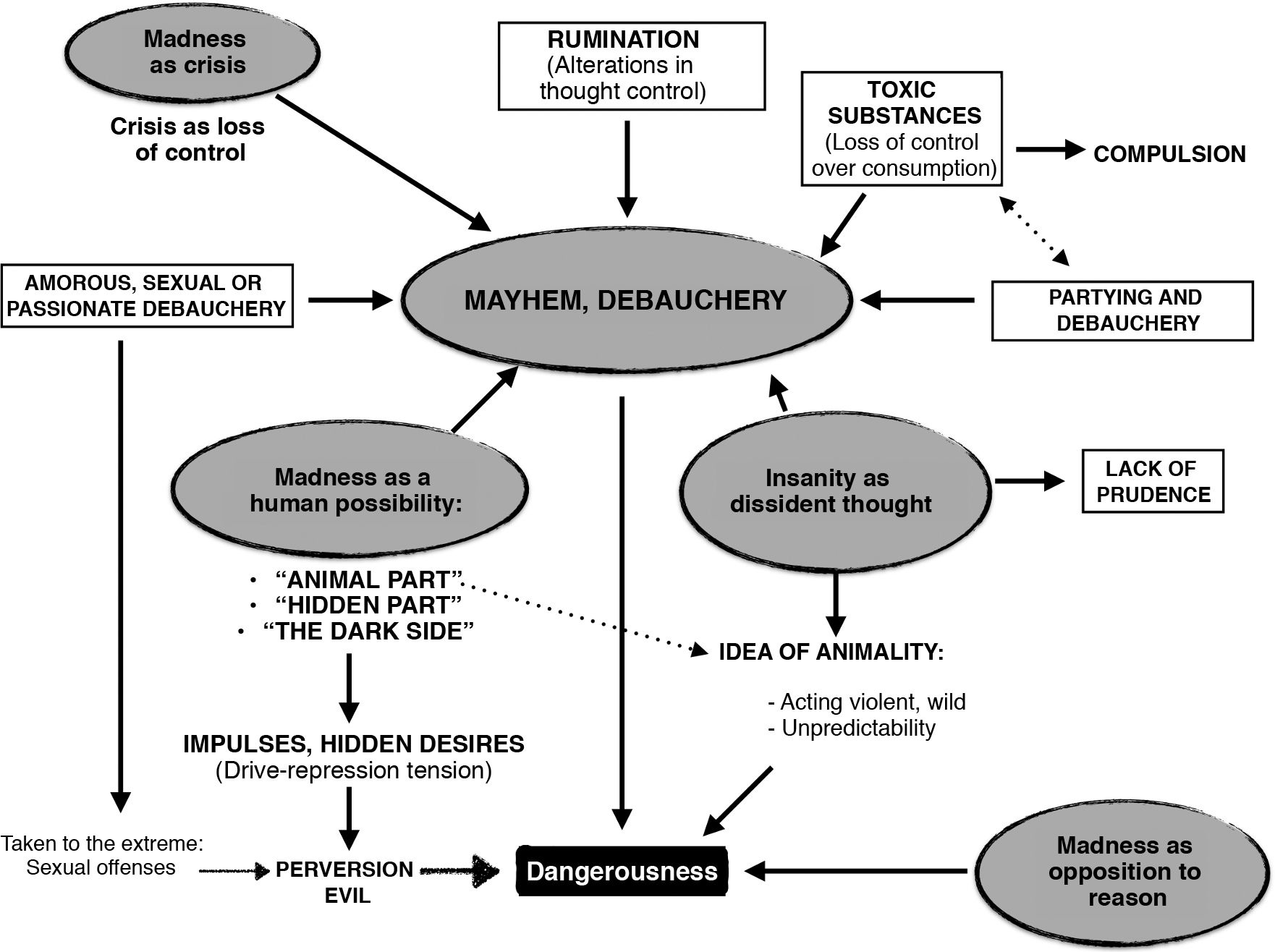

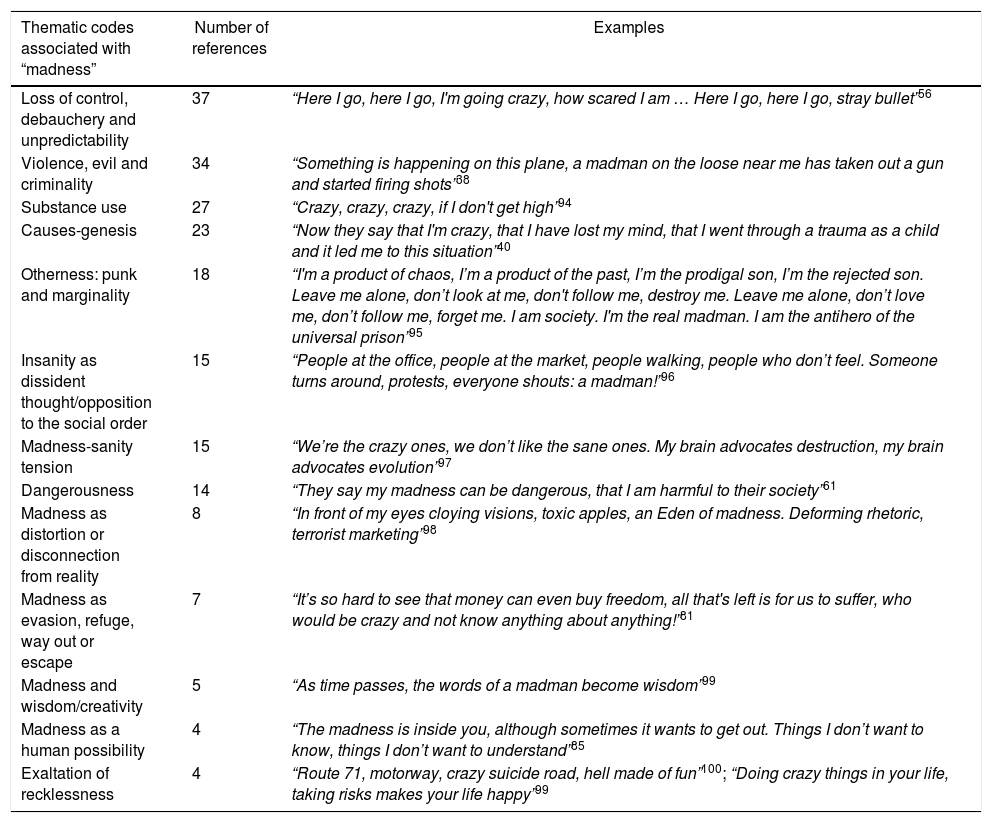

A total of 214 references were identified in the 163 songs. Among them, a great variety of thematic codes associated with the different uses of the word “madness” were found (Table 2). Each thematic code coexisted with at least one of the other subjects, on average, 80% of the time. Fig. 1 graphically summarises the identified relationships.

Thematic codes identified in association with the uses of “mad” or “madness” in 163 punk songs (Spain, 1981–2010).

| Thematic codes associated with “madness” | Number of references | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of control, debauchery and unpredictability | 37 | “Here I go, here I go, I'm going crazy, how scared I am … Here I go, here I go, stray bullet”56 |

| Violence, evil and criminality | 34 | “Something is happening on this plane, a madman on the loose near me has taken out a gun and started firing shots”38 |

| Substance use | 27 | “Crazy, crazy, crazy, if I don't get high”94 |

| Causes-genesis | 23 | “Now they say that I'm crazy, that I have lost my mind, that I went through a trauma as a child and it led me to this situation”40 |

| Otherness: punk and marginality | 18 | “I'm a product of chaos, I’m a product of the past, I’m the prodigal son, I’m the rejected son. Leave me alone, don’t look at me, don't follow me, destroy me. Leave me alone, don’t love me, don’t follow me, forget me. I am society. I'm the real madman. I am the antihero of the universal prison”95 |

| Insanity as dissident thought/opposition to the social order | 15 | “People at the office, people at the market, people walking, people who don’t feel. Someone turns around, protests, everyone shouts: a madman!”96 |

| Madness-sanity tension | 15 | “We’re the crazy ones, we don’t like the sane ones. My brain advocates destruction, my brain advocates evolution”97 |

| Dangerousness | 14 | “They say my madness can be dangerous, that I am harmful to their society”61 |

| Madness as distortion or disconnection from reality | 8 | “In front of my eyes cloying visions, toxic apples, an Eden of madness. Deforming rhetoric, terrorist marketing”98 |

| Madness as evasion, refuge, way out or escape | 7 | “It’s so hard to see that money can even buy freedom, all that's left is for us to suffer, who would be crazy and not know anything about anything!”81 |

| Madness and wisdom/creativity | 5 | “As time passes, the words of a madman become wisdom”99 |

| Madness as a human possibility | 4 | “The madness is inside you, although sometimes it wants to get out. Things I don’t want to know, things I don’t want to understand”85 |

| Exaltation of recklessness | 4 | “Route 71, motorway, crazy suicide road, hell made of fun”100; “Doing crazy things in your life, taking risks makes your life happy”99 |

Schematic representation of the relationships between the different thematic codes associated with the uses of “loco” [mad] and/or “locura” [madness] in 163 punk songs (Spain, 1981–2010). The arrows indicate the thematic codes that were related (in each arrow, the number of shared references).

Most of the references associated “madness” with loss of control, debauchery and unpredictability (17.29%; N = 37); secondly, with violence, evil and criminality (15.89%; N = 34), and thirdly, with the use of substances (12.62%; N = 27) (Table 2). The most relevant thematic groups are described below.

Punk, madness and mayhemThe relationships between madness, mayhem, debauchery and unpredictability constitute the most frequent thematic group. This was found linked to references to violence, criminality and dangerousness (together, 29.73%; N = 11) and, secondly, to the relationship between madness and substance use (24.32%; N = 9). Links with identity aspects of the subculture were also found (results are presented in the section “Punk otherness: madness and marginality”).

Criminal, violent and dangerousThirty-four references to criminality and violence were identified. The descriptions of crimes included 16 cases of homicide, two of robbery, two of sexual crimes and one of kidnapping. Two additional mentions of murders were identified. However, they did not describe the “madman” as the perpetrator34 or “madness” as the cause.35

In the 16 homicide descriptions, nine presented the “madman” as a murderer36–44; three attributed the murders to state policies or “mad governments”45–47; in two songs, the homicides appeared linked to the idea of madness as sexual tension or sadism48,49; and finally, in two songs the word “crazy” was alluded to in relation to homicidal behaviours,50,51 but rather expressing the idea of loss of control (“crazy to shoot”, “they have gone crazy”).

In most of the songs that linked “madness” and criminal behaviour (N = 12), there were no specific references to violence or dangerousness.

Regarding violence, six songs contained specific references (unrelated to the ideas of criminality or dangerousness).52–57 The descriptions identified comprised the following dimensions: social agitation52; intertextuality53; violence as one more dimension of life in society54; violence and “madness” attributed to machismo55; violence as a reaction or response to violence exerted by the social system56; and, finally, punk as a way of managing unpleasant emotional states or violent and destructive impulses: “I need to shake off my aggressiveness in a brutal dance. I need to break everything, go crazy … If you don't want to explode, you should de-stress”.57

Regarding the associations between “madness” and dangerousness, five songs presented specific references (with no relation to other overlapping themes).58–62 Of these, two focused on the dangerousness on the person himself, attributing it to “madness”: “they say my madness can be dangerous”61 or “get away from me (…) everyone will tell you that I'm a raving lunatic”.62 In the remaining three cases, the danger was attributed to third parties, in a critical context with social functioning.58–60 Finally, in six songs the idea of dangerousness was found coupled with violence or crime36–38,63–65 and in two cases, mayhem.66,67

Drugs, punk and madnessThis is the issue that, on an individual level, was most related to ideas of madness and lack of control. In the nine references that presented these associations, four cases linked loss of control with craving phenomena or withdrawal symptoms, three cases with states of intoxication and two cases with consumption in general (without specifying of what).

The second topic related to the use of toxic substances was that of the causes proposed for “madness” (N = 4; 14.81% of the references to “substances and madness”), whose results are set out in the corresponding section.

On the other hand, it was also possible to find relationships between the consumption of toxic substances and the ideas of madness and otherness (N = 3; 11.11%), that is, the use of substances coupled with “madness” as a sign of identity and a way of being different.

Finally, four references to the relationships between toxic substance consumption and madness coexisted with the associations between madness, avoidance or disconnection from reality (Fig. 1).

Regarding the substances specified in the different references, the most frequent was alcohol (N = 8), followed by LSD (N = 3) and cocaine (N = 2). Other substances described were: heroin (N = 1), amphetamines (N = 1), cannabis (N = 1), tobacco (N = 1) and inhalants (N = 1). Eleven references did not specify the type of toxic substance.

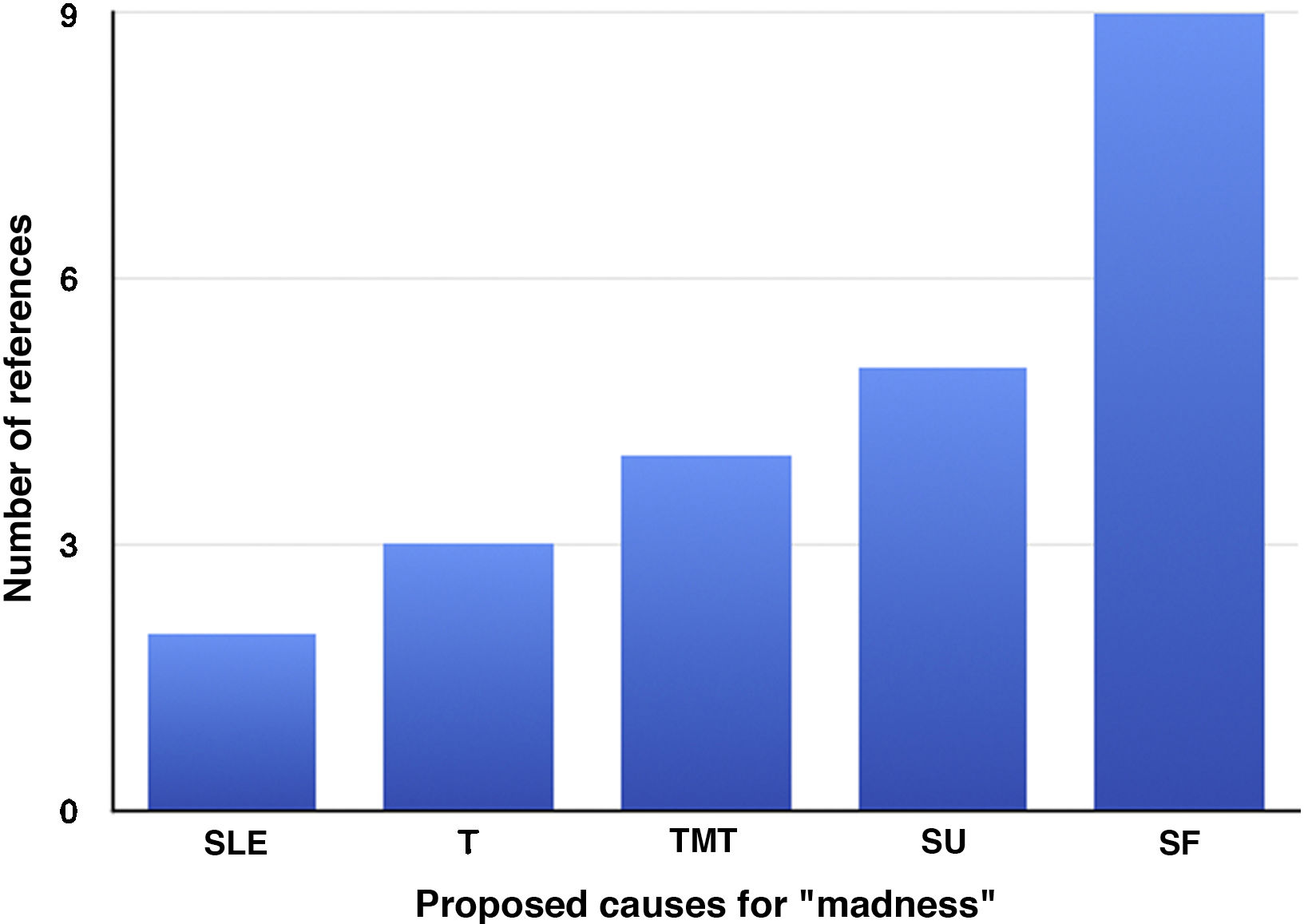

Madness and its causesTwenty-three references alluded to the causes of madness (Fig. 2). In six of them, social factors were described,37,42,44,68–70 including in two cases the expression “going crazy” as an equivalent to “loss of control”, while “madness” was associated with mood disorders, disappointment and disenchantment with the way of life and the functioning of society,68 or hatred and resentment resulting from social confrontation.69

In the rest of the songs with references to psychosocial causes, the description of “madness” associated with mass murders was striking. Among the attributed causes present in these songs there are: narcissistic-type psychological dynamics (“No one is alone because there is no one who can understand him, they cannot understand that he wants his chance never to be a nobody again”)37; copycat effect (“Nobody is someone you already know, finally he is front page news. And other nobodies are thinking of following in his footsteps”)36; violence in film and television (“Who educated his alienated mind? He always dreamed of the big screen. Being the best at shooting a gun, like his action hero”; “Who was to blame for so much horror? Maybe war or the television set (…) Days and nights of TV addiction, something burns inside him”)42,44; experiences of fear and humiliation (“blinded by humiliation, he decided to empty the magazine (…) hatred and revenge, the product of fear”).42

Regarding the descriptions of substance use, relationships were established between “going crazy” and the consumption of toxic substances in five songs, in two of which social conditions were added: current way of life and social organization,71 marginalisation and begging.72 Associations with psychotic symptoms were rarely explicit in this group of songs, alluding more generally to psychological distress. It was also possible to find allusions to loss of control73 and references to the use of television as an example of behavioural addiction: “It is difficult to go out when you are hooked. You are absorbed by images from another dimension, you are going crazy with so much video (…) watching so much television …”.74

On the other hand, in four cases the cause of “madness” was attributed to “thinking too much”, an expression whose equivalence is closer to anxious phenomena than psychotic ones: “You are going crazy from thinking too much, a lump in your throat, you have to vomit it up”.75 Meanwhile, the idea of “madness” as equivalent to “despair” appeared in two cases.76,77 In both, the presence of adverse life events (diagnosis of terminal illness, hospitalisation, agony, loss of freedom) was attributed as the cause.

Finally, in three songs it was possible to find references to trauma as a factor related to the origin of madness: “Now they say that I am crazy, that I have lost my mind, that I went through a trauma as a child and it led me to this situation”.40

Disconnected: madness as an escapeThe thematic overlap was high between the references to madness as a disconnection or distortion of reality and those that exhibited it as an exit or escape from an intolerable reality.

In the songs analysed, those who are socially comfortable, have no contact with a majority reality or do not understand the needs of a disadvantaged majority “is disconnected”: “Swindling politicians have the power, led by a madman who doesn't want to see anything …”,78“What is the president laughing at, if his prisons are full of people? (…) Could it be how well his current account is doing or has the president gone crazy?”.79 On the other hand, it is implicitly proposed that those who do not enjoy a socially comfortable position “disconnect” in order to “deactivate”, through evasion and the concealment or distortion of reality (television, media, marketing, football, drugs, etc.).

As for the distortion of reality, on the one hand, there appears the idea of an intentional distortion (marketing, subliminal power, the media, among others), as anticipated in the previous paragraph, in order to hide, cancel and appease, and, on the other hand, the implicit idea –although a minority in terms of frequency– of an unintended distortion of reality as a result of states of infatuation.

It was also possible to identify songs where madness appears as a desired state, a refuge: “Don’t let it abandon me, I don’t want it to go, madness is the refuge and there I hide my soul”.80 In some cases, the use of toxic substances (colloquially referred to as “ponerse ciego” [getting wasted] in the example cited below) appears as a way of accessing altered mental states (“being crazy”) to evade reality: “It’s so hard to see that money can even buy freedom, all that's left is for us to suffer, who would be crazy and not know anything about anything! But I'm getting wasted and I have to hide …”.81

Punk, dissident thought and madness: the otherness of the madmanDespite not being the majority, there were recurring explicit references to dissident thought as “madness” or to the “madman” as a critic of the social order. Despite the fact that this topic bears similarities with the “madness-sanity” dichotomy (a category with frequent allusions to a “sick” or “crazy” social system), the thematic overlap between the two was low (four shared references out of a total of 26).

Punk otherness: madness and marginalityIn 18 references, the idea of otherness was explicitly identified (Table 2). The concept of otherness is a common notion in different branches of the social sciences. In general, it can be described as a means of identity-shaping by recognising a different other. At the social level, this process will lead to the generation of subordinate groups where some subjects will embody the norm (valued identity) in opposition to the “other”, usually devalued.82 Thus, in the songs analysed, the “madman” is exhibited as a social “other”, part of an excluded, marginal and different minority. The appraisal of this difference and the distancing of the majority contribute to the shaping of identity aspects, a “crazy” way of being that historically has been related to the distinctive features of rock, in general, and punk, in particular: “my madness mixes with your acceleration (…) it shows, it feels, we know we are different”83; “Making madness a way of life”.84

In three cases, madness as an expression of punk otherness constituted the thematic core by itself. Thus, the most common was that it was found as a complementary or superimposed theme on others. In 15 of the 18 references, there were associations with other thematic areas (dissident thinking, madness-sanity tension, use of toxic substances, dangerousness, mayhem, causes of madness).

Madness as a human possibilityAlthough a minority theme in terms of references (N = 4), the idea of madness as a human possibility is an interesting aspect identified in Spanish punk songs.85–88 In this regard it was possible to find references to the irrationality of human nature (exhibited through war conflicts): “Illusions and feelings are now food for the black flowers of man's madness”,87 as well as a “hidden” part that exists in human beings and that in certain situations can “come out” and show itself: “(I’m) going to let go, to release my fears, to show the madman that we all hide …”86; “Madness is inside me, although sometimes it wants to get out”.85

DiscussionThe coexistence of various themes associated with madness was the norm. This is due, on the one hand, to the fact that the contents of the songs are not usually monographic and, on the other, because different themes may be related in some cases and, in others, express different nuances within a thematic area to which they are subordinate. For example, it is plausible to suggest relationships between substance use and loss of control, debauchery and unpredictability. Thus, the use of toxic substances may correspond to a manifestation (or cause) of loss of control or behavioural disturbances, or be closely related to the idea of debauchery. Similarly, links between the themes “madness and substance use” and “madness as evasion or disconnection from reality” can be hypothesised. However, when analysing the overlap between themes, the aforementioned relationships were only identified in a minority of cases within a wide variety of thematic associations.

Regarding the ideas of disconnection and distortion of reality, none of the cases coincided with the loss of reason or judgement in a psychopathological sense. In some songs, “disconnecting” appeared as a way out: evasion and escape from a reality that becomes intolerable. This idea could also be identified in some cases in relation to substance use. In these, the ideas of madness closest to psychosis portrayed disconnection from reality as a solution or escape.

Regarding the proposed causes for “madness”, it is important to contextualise that they did not necessarily allude to causes for psychoses, since - as has been suggested previously - the concept of “madness” refers to a cultural term whose uses and meanings exceed the specific area of psychotic disorders. However, among those songs that alluded to “madness” as psychosis, the effect of traumatic events was the most present (and probably the most explicit) causal factor in the Spanish punk imagination.

The otherness of the “madman” was manifested as a critical reflection of the social system, showing similarities with those references to the madness-sanity dichotomy. In this sense, it could be argued that both thematic groups are manifestations of the same idea (critical views of the social system), only that in one case the figure of the “madman” is the dissident person while, in the other, the “madness” is attributed to the social organisation, the political or economic system. Thus, the question that remains is “who is the madman?” The truth is that, at the level of ideological differences, the figure of the “madman” is always attributed to an “other”; that is, the dissident is a “madman” for the social majority, while the social system is described as “mad” by those who have an opposite view, evidencing the underlying power dynamics where the madman occupies the position of devalued identity, after their labelling and subsequent separation. In short, the madman is “the other”: “I walk on one side, you walk on the other. Tell me who will be right: you, me, or neither of us. You think I’m crazy. I think you're crazy”.89

Regarding the more constructive dimensions, it is worth highlighting the references to the use of music as a coping mechanism, an aspect that has been described in other musical genres, such as heavy metal.90

Finally, it was possible to intuit some relationships with ideas coming from psychoanalysis (first and second topology). These may have penetrated the popular imagination, allowing certain rudiments of the ideas of repression or the unconscious to be identified in the reviewed content: “Madness lurks behind the doors of my mind, like glass in a thousand pieces tearing the subconscious”.88 In a sense, the idea of madness as a hidden and repressed part of human nature is related to ideas from Fusar-Poli and Madini,91 who referring to the Pink Floyd song The Dark Side of the Moon argue that “the dark side of the moon” (a part that is “always there, though invisible, waiting to be exposed”) would correspond to a metaphor of madness, or more globally, of human irrationality. The authors alternatively propose that “the dark side of the moon” could reflect that hidden side that is presumed present in every human being, an equivalent to the Freudian idea of the unconscious91 and, more precisely, the Jungian archetype of the shadow.92

Although assumed to be part of human nature, it is important to take into account how that hidden side connects with the idea of animality. Thus, a hidden facet of the human being includes his wild, instinctual and animal side. This equivalence between madness and animality (and, therefore, irrationality, mayhem, violence and, ultimately, dangerousness), despite being proclaimed in many of the songs analysed, is part of one of the negative visions of madness that are found throughout history.

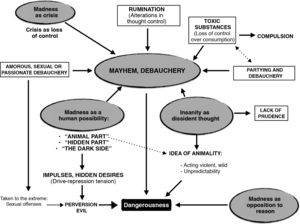

In light of our data, it is possible to propose the hypothesis of dangerousness as a common final route for a good number of the issues identified, which leads to the establishment of an idea of insanity that promotes stigmatisation. As represented in Fig. 3, madness as loss of control is at the base of different identified themes (madness as crisis, madness as rumination, madness and consumption of toxic substances, madness as partying or amorous debauchery); in turn, the themes “madness as opposition to reason” and “madness as human possibility” converge towards the idea of animality, where the acting out of impulses, unpredictability and wild and violent actions are close to the idea of debauchery and mayhem. This “wild”, “animal”, “unbridled” or “out of control” behaviour leads towards the connotation of dangerousness. The topic “madness as dissident thought” completes the picture, where the challenge to the social order is understood as dangerous in itself, at the same time that it connects with the idea of crisis, social disorder and chaos. Thus, the negative evaluations of madness and the madman can be largely explained by the attributions of dangerousness that they are the object of.

Dangerousness as a common final path for negative representations of insanity. Violence and crime are not included in the graph, given their direct link with the idea of dangerousness. Some of the violent and criminal acts described in the analysed songs may be included in the themes “Madness as opposition to reason” and “Madness as human possibility”.

McDonald23 has highlighted how some songs with provocative lyrics evoke the most violent imagery in psychiatry. Along the same lines, a kind of rhetoric of shock is suggested through madness as a staging of self-marginalisation and opposition, so typical of punk, to socially acceptable behaviours.

For his part, Thompson92 proposes noise as the sound emulation of madness, since reason is posed as a domain of language and noise would correspond to “the incomprehensible”. The noise and the punk aesthetic appeal to abjection, repulsiveness, fostering a mixture of fear and fascination.92 Thus, the associations established between violence, crime, evil, dangerousness and madness were not uncommon in our sample.

In short, madness is constituted as one of the forms of expression of the punk identity built from opposition to and difference from the social moulds of the majority, proclaiming itself as a challenge to normality and order, as well as a danger to society. Thus, the other is not only different or devalued, it is also dangerous.

TA allowed us to understand how the idea of otherness, so important in the identity affirmation of the punk subculture, can be expressed through the figure of the madman, encompassing provocative dimensions that challenge social patterns by exalting madness. Thus, madness as a staging of punk otherness is a theme that can be found, to a greater or lesser extent, as a backdrop to the various other themes. For example, the appraisal of debauchery, mayhem and unpredictability attributed to madness, as well as the exaltation of recklessness, are part of the hallmarks of punk (idea of chaos); the consumption of toxic substances can also be found in the service of identity construction or as a form of evasion, escape or self-marginalisation. Insanity as a thought opposed to the established order constitutes another of the facets of otherness, as well as many cases that express the health-disease, madness-sanity, normality-abnormality tension: “We abhor normal life, we go headlong towards our end. Only by turning everything upside down will we be able to stand up. Damn normality! (…) I want to be crazy, damn rules, fucking legality!”.93 In the relationships established between wisdom and madness, and even in the provocative exaltation of violence, criminality and social dangerousness, it is possible to find traces of punk otherness. In this way, although it is not explicitly found in the majority of references, it is impossible to think about the social representations of madness in punk without taking this dimension into account.

Finally, the study of the social representations of mental disorders through the examination of the productions of popular culture can bring us closer to the uses and meanings present in a given population. Future studies focusing specifically on the descriptions of psychoses, as well as the replication of this work in other subcultures and populations, are necessary to advance in this field of knowledge. Moreover, the analysis of the impact of this content on the attitudes and dispositions of the audiences is an area that is not yet broadly explored and open to investigation.

Ethical aspectsNon-interventional study that uses public data, without personally identifiable private information.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

| Song title | Performer | Year | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| N XX | Piorreah | 1981−1985 | Excluded |

| Libertad [Liberty] | Delincuencia Sonora | 1981−1985 | |

| Negocios sucios [Dirty business] | Los Nikis | 1981 | |

| El cobrador loco [The mad debt collector] | Siniestro Total | 1982 | |

| Locos por los mantecados [Crazy for mantecado cakes] | Asesinos a Sueldo | 1982 | |

| Sangre en el museo de cera [Blood in the wax museum] | Los Nikis | 1982 | |

| Hospital | Larsen | 1983 | |

| Fuckin’ shit | Shit S.A. | 1984 | |

| Soy un producto [I’m a product] | Kangrena | 1984 | |

| Canción bestia (2.ª parte) [Beast song (Part 2)] | Subterranean Kids | 1985 | |

| El maestro [The teacher] | Desechables | 1985 | |

| Gente [People] | Subterranean Kids | 1985 | |

| La tortura [Torture] | La Polla Records | 1985 | |

| Problemas de estado [State problems] | Interterror | 1985 | |

| Vuestra maldición [Your curse] | La Polla Records | 1985 | |

| En casa me llaman loco [They call me mad at home] | Subterranean Kids | 1986 | |

| Fuck furcias [Fuck whores] | Cicatriz | 1986 | |

| La naranja no es mecánica [The orange is not clockwork] | Los Nikis | 1986 | |

| Sentimientos y venganzas [Feelings and revenge] | Zer Bizio? | 1986 | |

| Alimento para las flores [Flower food] | Ruido de Rabia | 1987 | |

| Ciervos, corzos y gacelas [Deer, roebuck and gazelle] | La Polla Records | 1988 | Excluded |

| Dorian Grey | Canívales Podridos | 1988 | |

| Víctimas de su poder [Victims of their power] | Tijuana in Blue | 1988 | |

| Antilíder [Anti-leader] | Psicosis Crítica | 1989 | |

| Cuidado [Careful] | Psicosis Crítica | 1989 | |

| Tango: nostalgia de ella [Tango: nostalgia for her] | Decibelios | 1989 | |

| Video Killer | Decibelios | 1989 | |

| En las montañas de la locura [In the mountains of madness] | Vómito | 1990 | Excluded |

| Licantropía [Lycanthropy] | Tijuana in Blue | 1990 | |

| Mirando al abismo [Looking into the abyss] | Vómito | 1990 | |

| Ruta 71 [Route 71] | Delincuencia Sonora | 1990 | |

| Sin pena ni gloria [Without pain or glory] | Boikot | 1990 | |

| Vete lejos de mi [Get away from me] | Vómito | 1990 | |

| Cienzia asesina [Killer science] | Soziedad Alkohólika | 1991 | |

| Elementos retóricos de la descomposicón [Rhetorical elements of decomposition] | Ruido de Rabia | 1991 | |

| Fatídico culebrón [Fateful soap opera] | Tijuana in Blue | 1991 | |

| Kuerpo a kuerpo [Body to body] | Parabellum | 1991 | |

| Loco [Mad] | Cicatriz | 1991 | |

| Noche acelerada [Accelerated night] | El Último ke Zierre | 1991 | |

| Qué mogollón [What a shitload] | El Último ke Zierre | 1991 | |

| Ritual | Cerebros Exprimidos | 1991 | |

| Trasgutoma | Boikot | 1991 | Excluded |

| Insumisión [Insubordination] | Pota Potaje | 1992−1995 | Excluded |

| Fuego y cristal [Fire and glass] | La Polla Records | 1992 | |

| La historia se repite [History repeats itself] | Reincidentes | 1992 | |

| La matanza extremeña [The Extremadura massacre] | A Palo Seko (Extremadura) | 1992 | |

| Prisión confortable [Comfortable prison] | HHH | 1992 | |

| Sueños enfermos [Sick dreams] | Boikot | 1992 | Excluded |

| Ariel Ultra | Soziedad Alkohólika | 1993 | Excluded |

| Atomizador [Atomizer] | Ruido de Rabia | 1993 | Excluded |

| Cobra Kahn | Los Vegetales | 1993 | |

| El parto [The birth] | El Último ke Zierre | 1993 | |

| La carne [Meat] | El Último ke Zierre | 1993 | |

| La locura [Madness] | Parabellum | 1993 | |

| La viuda [The widow] | Reincidentes | 1993 | |

| Me hago el loco [I'm becoming the madman] | El Último ke Zierre | 1993 | |

| Otra vez [Again] | Reincidentes | 1993 | |

| Último sueño [Last dream] | Escombro | 1993 | |

| Verdad o mentira [Truth or lie] | Parabellum | 1993 | |

| Desobedece [Disobey] | Subversión X | 1994 | |

| Dos colegas [Two friends] | Reincidentes | 1994 | |

| El cuento del alfajor [The story of alfajor] | Reincidentes | 1994 | |

| Exclusiva [Exclusive] | Ataúd Vacante | 1994 | |

| Harry lo hace por ti [Harry does it for you] | La Polla Records | 1994 | |

| Políticos [Politicians] | Mentes Torturadas | 1994 | |

| Viaje al infierno [Journey to hell] | Subversión X | 1994 | |

| Desquiciado [Unhinged] | Cerebros Exprimidos | 1995 | |

| Kanzión de amor [Love song] | Manolo Kabezabolo | 1995 | |

| Kuando revientes [When you burst] | Manolo Kabezabolo | 1995 | |

| La voz de la conciencia [The voice of conscience] | Sálvate Si Puedes | 1995 | |

| Locura [Madness] | Cerebros Exprimidos | 1995 | |

| Nadie me obliga a cuidarme [Nobody forces me to take care of myself] | El Último ke Zierre | 1995 | |

| No penséis que olvido [Don't think I forget] | El Último ke Zierre | 1995 | |

| No puedo soportar [I can't stand it] | Manolo Kabezabolo | 1995 | |

| Salto al vacío [Leap into the void] | Vómito | 1995 | |

| Viva yo y mi kaballo [Long live me and my horse] | Manolo Kabezabolo | 1995 | |

| ¿De qué se ríe el señor presidente? [What is the president laughing at?] | Alloraralaiglesia | 1996 | |

| Gol en el campo [Goal on the pitch] | La Polla Records | 1996 | |

| Cerebros Exprimidos [Squeezed brains] | Cerebros Exprimidos | 1997 | |

| Corre [Hurry] | Reincidentes | 1997 | |

| Cuando nada vale nada [When nothing is worth anything] | Soziedad Alkohólika | 1997 | |

| Ningún valor [No value] | Skalariak | 1997 | |

| Soñando angelitos [Dreaming of little angels] | Ostia Puta | 1997 | |

| Conéctate [Get connected] | Segismundo Toxicómano | 1998 | |

| Dejadme [Leave me] | El Último ke Zierre | 1998 | |

| El dinero [Money] | El Trono de Judas | 1998 | |

| Familia de subnormales todos locos [Family of morons all crazy] | Airbag | 1998 | |

| George Orwell | Segismundo Toxicómano | 1998 | |

| Homenajes y tributos [Salutes and tributes] | A Palo Seko | 1998 | |

| La rabia [Rage] | El Trono de Judas | 1998 | |

| Nada nuevo [Nothing new] | Eskorbuto | 1998 | |

| Odio a la nueva mayoría [I hate the new majority] | El Último ke Zierre | 1998 | |

| ¡¡Oh no!! | Andanada 7 | 1998 | |

| Pesadilla [Nightmare] | HHH | 1998 | |

| Rekuerdos [Memories] | Envidia Kotxina | 1998 | |

| Dale acción [Give it action] | Canallas | 1999 | |

| Descontrol [Mayhem] | Trastienda RC | 1999 | |

| Rebelión de neuronas [Neuron rebellion] | Canallas | 1999 | |

| Ya no quiero ser yo [I don't want to be me anymore] | La Polla Records | 1999 | |

| El ladrón de tumbas [The grave robber] | El Último ke Zierre | 2000 | |

| La salvaora [The saviouress] | El Último ke Zierre | 2000 | |

| Odio [Hate] | Segismundo Toxicómano | 2000 | |

| Terror en el garaje [Terror in the garage] | Airbag | 2000 | |

| Años de amargura [Years of bitterness] | Envidia Kotxina | 2001 | |

| Engorilando [Getting angry] | Sikarios | 2001 | |

| Esta soziedad [This society] | Envidia Kotxina | 2001 | |

| Hasta los huevos [Sick and tired] | Segismundo Toxicómano | 2001 | |

| La duda [Doubt] | Asto Pituak | 2001 | |

| Las drogas [Drugs] | Segismundo Toxicómano | 2001 | |

| No les ladréis a los perros que luego cogen acento de fuera [Don’t bark at the dogs because then they take on a foreign accent] | Asto Pituak | 2001 | |

| No quiero ser un Rolling Stone [I don’t want to be a Rolling Stone] | La Polla Records | 2001 | Excluded |

| Tiempos locos [Mad times] | El Trono de Judas | 2001 | |

| Vueltas y vueltas [Round and round] | Kaótiko | 2001 | |

| La vida loca [The mad life] | The Kagas | 2002 | |

| Último vis a vis [Last face to face] | El Último ke Zierre | 2002 | |

| Cementerio de lobos [Wolf cemetery] | El Último ke Zierre | 2003 | |

| Deskiziao | Envidia Kotxina | 2003 | |

| En tu honor [In your honour] | Skontra | 2003 | |

| Loco mambo [Mad mambo] | La Polla Records | 2003 | |

| Locos [Madmen] | Karnvapen Attack | 2003 | |

| Mi kompañera la lokura [My mate the madman] | Envidia Kotxina | 2003 | |

| Ondas combativas [Combative waves] | El Trono de Judas | 2003 | |

| Rincones [Corners] | La Polla Records | 2003 | |

| Rock and roll | Sikarios | 2003 | |

| Visto lo visto [By the looks of it] | Kaótiko | 2003 | |

| Carnaval [Carnival] | The Meas | 2004 | |

| Desquiciadamente [Derangedly] | Subversión X | 2004 | |

| El Mendigo [The beggar] | Brote Sikótiko | 2004 | |

| Historias nocturnas (del lugar donde reina la locura) [Night-time stories (from the place where madness reigns)] | Subversión X | 2004 | |

| La lombriz [Earthworm] | Chamarreta | 2004 | |

| Miedo [Fear] | Segismundo Toxicómano | 2004 | |

| Niños sin juguetes [Kids without toys] | Escuela de Odio | 2004 | |

| Una noche destructiva [A destructive night] | Subversión X | 2004 | |

| Chitón [Hush] | Fe de Ratas | 2005 | |

| Esclavos [Slaves] | Reincidentes | 2005 | |

| Estoy en la luna [I’m on the moon] | Porretas | 2005 | |

| Kamikaze | Segismundo Toxicómano | 2005 | |

| Ke no me la cuentes [Don’t tell me] | Segismundo Toxicómano | 2005 | |

| Mente [Mind] | Gatillazo | 2005 | |

| Perdedor [Loser] | Segismundo Toxicómano | 2005 | |

| Ven a ver [Come and see] | Segismundo Toxicómano | 2005 | Excluded |

| Vuelve el hombre [The man comes back] | Gatillazo | 2005 | |

| La mirada perdida [The lost look] | Kaótiko | 2006 | |

| Llueven cristales [It’s raining glass] | Trastienda RC | 2006 | |

| Locos de atar [Raving lunatic] | Reincidentes | 2006 | |

| No te puedes rendir [You can’t give up] | Brote Sikótiko | 2006 | |

| Cristales en mi mente [Windows in my mind] | Sikótiko | 2007 | |

| El papel arde muy bien [Paper burns very well] | El Trono de Judas | 2007 | |

| Escupiré mi ruina [I will spit out my ruin] | Fe de Ratas | 2007 | |

| Igual que caigo yo [Just like I fall] | Skontra | 2007 | |

| La vida en un asalto [Life in an assault] | Josu Distorsión y Los del Puente Romano | 2007 | |

| Loca [Madwoman] | Fe de Ratas | 2007 | |

| No es verdad [It’s not true] | El Último ke Zierre | 2007 | |

| Para agarrarme [To grab me] | El Último ke Zierre | 2007 | |

| Tiembla [It shakes] | Fe de Ratas | 2007 | |

| Vais de pacifistas [You go as pacifists] | El Trono de Judas | 2007 | |

| Vivo en el infierno [I live in hell] | Sikótiko | 2007 | |

| Bubamara | Boikot | 2008 | Excluded |

| Dando vueltas en la kama [Turning over in bed] | Manolo Kabezabolo | 2008 | |

| Fuego y miedo [Fire and fear] | SKA-P | 2008 | |

| Insultos varios [Various insults] | Gatillazo | 2008 | |

| Nadie [Nobody] | Soziedad Alkohólika | 2008 | |

| Por la razón o la fuerza [For truth or power] | The Locos | 2008 | |

| Y si no hay viento habrá que remar [If there's no wind we'll have to row] | Escuela de Odio | 2008 | |

| Zona Glam [Glam zone] | Gatillazo | 2008 | |

| El diablo [The devil] | Subversión X | 2009 | |

| Espiral I [Spiral I] | La taberna de Moe | 2009 | |

| La herida (yo y mi verdugo) [The wound (me and my executioner)] | Subversión X | 2009 | |

| Loco [Mad] | Vendetta | 2009 | |

| No es pecado [It’s not a sin] | El Último ke Zierre | 2009 | |

| Solo [Alone] | Recsaka Permanente | 2009 | |

| Un poco más [A little more] | El Último ke Zierre | 2009 | |

| No podrán [They won’t be able to] | The Birras Terror | 2010 | |

| Tú también puedes venir [You can come too] | The Birras Terror | 2010 |

Please cite this article as: Pavez F, Saura E, Marset P. «Estamos como una cabra»: un análisis temático de la locura en la música punk española (1981–2010). Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:116–129.

![Schematic representation of the relationships between the different thematic codes associated with the uses of “loco” [mad] and/or “locura” [madness] in 163 punk songs (Spain, 1981–2010). The arrows indicate the thematic codes that were related (in each arrow, the number of shared references). Schematic representation of the relationships between the different thematic codes associated with the uses of “loco” [mad] and/or “locura” [madness] in 163 punk songs (Spain, 1981–2010). The arrows indicate the thematic codes that were related (in each arrow, the number of shared references).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/25303120/0000005000000002/v1_202106050654/S2530312021000291/v1_202106050654/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)