The COVID-19 Fear Scale (FCV-19S) is the most widely used instrument to assess fear of coronaviruses. Although preliminary analyses of the Brazilian–Portuguese version showed promising data for the 7-item version, several studies in Latin America suggest that the 5- and 6-item versions present better psychometric indicators.

ObjectiveTo replicate and compare the Brazilian–Portuguese version of the (FCV-5S), studying its homogeneity and dimensionality.

MethodsA total of 1003 adults between 18 and 78 voluntarily participated. The data were analyzed through exploratory factorial analysis and structural equations modeling. A Multiple Indicators and Multiples Causes model (MIMIC) was used to check the differential functioning of each item regressed on age. Likewise, Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega were calculated for FCV-5S. Finally, as a test of nomological validity, the mean scores and standard deviation between men and women were compared after testing similarity invariance.

Results73.3% were younger adults (18–44 years old), 71.3% were women, and 59.7% had a university education. The 5-item version (FCV-5S) of the COVID-19 Fear Scale has better goodness-of-fit indicators than the 6-item version for a one-factor structure. FCV-5S accomplish with invariance by gender and partial invariance by age in the general population of Brazil.

ConclusionsThe FCV-5S has a dimensional structure with partial invariance by gender and age and can be used to assess COVID-19 fear in the general population in Brazil.

La escala de miedo COVID-19 (FCV-19S) es el instrumento más utilizado para evaluar el miedo al coronavirus. Aunque los análisis preliminares de la versión brasileño-portuguesa mostraron datos promisorios para la versión de 7 ítems, varios estudios en América Latina sugieren que las versiones de 5 y 6 ítems presentan mejores indicadores psicométricos.

ObjetivoReplicar y comparar la versión brasileño-portuguesa de la FCV-5S estudiando su homogeneidad y su dimensionalidad.

MétodoParticiparon voluntariamente 1.003 adultos de entre 18 y 78 años. Los datos se analizaron mediante análisis factorial exploratorio y modelización de ecuaciones estructurales. Se utilizó un modelo de Indicadores Múltiples y Causas Múltiples (MIMIC) para comprobar el funcionamiento diferencial de cada ítem sobre la edad. Asimismo, se calcularon el alfa de Cronbach y el omega de McDonald para la FCV-5S. Por último, como prueba de validez nomológica, se compararon las puntuaciones medias y la desviación típica entre hombres y mujeres tras comprobar la invarianza de similitud.

ResultadosEl 73,3% fueron adultos más jóvenes (18-44 años), el 71,3% mujeres y el 59,7% tenían estudios universitarios. La versión de 5 ítems (FCV-5S) de la escala de miedo COVID-19 presenta mejores indicadores de bondad de ajuste que la versión de 6 ítems para una estructura unifactorial. La FCV-5S presentó invarianza por género e invarianza parcial por edad en la población general de Brasil.

ConclusionesLa FCV-5S tiene una estructura dimensional con invarianza parcial por género y edad y puede ser utilizada para evaluar el miedo a la COVID-19 en la población general de Brasil.

The high infection, mortality rates of COVID-19 brought a significant increase in fear and anxiety levels, which increased the damage caused by the disease.1,2 In addition, COVID-19 has generated in the population a sense of insecurity, symptoms of anxiety and depression.3–5

Brazil had the highest rates of COVID-19-related infections and deaths in Latin American.6 The chances of developing mental health disorders in Brazil due to the pandemic were higher than in European countries and are related to aggravated socioeconomic issues during the pandemic.7 Considering the impact of COVID-19 on mental health worldwide, it is critical to develop studies about this issue to comprehend and better understand short- and long-term effects on the general population.8 The main instrument to measure some mental health effects of the pandemic is the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S). It has been validated and used in several languages and cultures.1,9,10

The original scale was developed in Iran.1 Other studies were designed to produce more psychometric evidence and evaluate the scale in different settings.11,12 A first Brazilian–Portuguese version was validated, showing promising evidence about the FCV-19S, using preliminary analysis and maintaining the 7-item structure.13

The FCV-19S Scale was assessed in 1687 Colombians adults; exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were performed and a 5-item and 6-item version presented better indicators, showing promising evidence about those shorter versions.14 This 5-item version of the FCV-19S was also evaluated in the general population in Argentina, showing a stable unidimensional structure, good internal consistency and invariance by age group.15 Shorter versions of the measurement instruments offer greater guarantees of unidimensionality, and more reproducible psychometric indicators in different contexts and samples.16 However, the Fear COVID-5 (FCV-5S) Scale has not been evaluated in the Brazilian population. Therefore, the present study aims to replicate and compare the Brazilian–Portuguese version of the (FCV-5S), studying its homogeneity and dimensionality.

Methods sample and data collection proceduresA total of 1003 adults voluntarily participated in an online survey using a snowball sampling strategy. The inclusion criteria were being a Portuguese-speaking resident in Brazil, being 18 years or older. Participants were recruited from online advertisements, e-mail campaigns, TV and radio campaigns, social media. Informed consent was obtained electronically before data were collected from the participants.

MeasurementsSociodemographic variablesWe evaluate sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, educational level, and employment status.

Fear of COVID-19The Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) was developed by Ahorsu et al.1 The original scale is made up of seven items that offer five levels of agreement as a response: “Totally disagree,” “disagree,” “neither agree nor disagree,” “agree,” and “totally agree.” The answers are scored from 1 to 5, with scores between 7 and 35. For comparison purpose, the current study, we used the Colombian version14 which consists of 6 items and four answer options: “never,” “seldom,” “almost always” and “always.” The higher the score, the greater the fear of COVID-19. The frequency was preferred over the agreement in the response pattern by the most culturally relevant linguistic use for a symptom.17 Similarly, an even number of options were taken to avoid the central response's tendency in the cases of odd options.18 We used similar procedures for replication proposals. The Colombian version of FCV-19S was translated from Spanish to Portuguese language. First, the scale was translated by a researcher expert in psychometrics, fluent in Spanish and Portuguese. Then, another translator with background in Psychology, who is fluent in Spanish and Portuguese, proceeded the back-translation of the Portuguese version into Spanish, and the difference with the version of the independent translator was discussed. Both direct and reverse translations were compared to determine equivalence, and cultural appropriateness was verified between authors. The translation into Portuguese approved by the research team went to the second stage of evaluating appearance validity.

Statistical analysisThe data were analyzed through exploratory factorial analysis and structural equations modeling using R version 3.5.3 and RStudio version 11.463. In the first part, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out using psych package19 after proving that the items met a latent factor with the Bartlett sphericity test,20 and the Kaiser sample adequacy test-Meier-Olkin, KMO,21 communalities, factor loadings, Eigenvalue and explained variance were observed for Fear of COVID-6 Scale. Likewise, Cronbach's alpha,22 and McDonald's omega were calculated as internal consistency measures.23

Next, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using lavaan package,24 and Satorra-Bentler's chi-square, chi-square/df, RMSEA, CFI, TLI, and SRMR were calculated using as estimator a weighted least squares adjusted by means and variances (WLSMV) taking into account the ordinal level of measurement of the items. Given the lack of acceptable fit, several versions of five items were tested. The only version with a satisfactory fit was the one from which item 4, (FCV-5S), was omitted. For the (FCV-5S), the steps of an EFA were repeated with the calculation of KMO, Bartlett's test, communalities, factor loadings, eigenvalue, and percentage of the explained variance. Subsequently, mean, standard deviation, corrected correlation between an item and total score, and Cronbach's alpha were observed if the item was omitted. In the CFA, good indicators of fit were calculated for the total sample and by gender. This approach was taken as a measure of invariance of the instrument.

A Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Analysis was conducted using semTools package25 to check internal validity testing the hypothesis of invariance among gender considering the same ordinal structure with WLSMV estimator and theta parameterization. The samples were compared based on the configural (same item structure), metric (same item structure and factorial loadings), scalar (all previous constraints plus same thresholds) and latent averages models of invariance. This last one level considered all previous levels of invariance and additional equality between latent mean. Considering the fact that the large size of the samples makes it more likely that the chi-squared values will present significant differences lower than 0.01, differences in the CFI of each model were considered as evidence of invariance.26 A Multiple Indicators and Multiples Causes model (MIMIC) was used to check the differential functioning of each item regressed on age. Likewise, Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega were calculated for FCV-5S. Finally, as a test of nomological validity, the mean scores and standard deviation between men and women were compared after testing similarity invariance; a significantly higher score was expected in women.27

ResultsA total of 1003 of adults participated in the final analysis. The age of participants was between 18 and 78 (M=35.0159521, SD=14.1081418, ME=30, IQR=23–46). Younger adults (age 18–44) were more frequent (73.3%), female (71.3%), college or university education (59.7%), single (58.4%) and employed (83.0%) (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics (N=1003).

| Overall (N=1003) | |

|---|---|

| Age_years | |

| 18–29 | 488 (48.7%) |

| 30–44 | 247 (24.6%) |

| 45–64 | 251 (25.0%) |

| 65 or more | 17 (1.7%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 715 (71.3%) |

| Male | 288 (28.7%) |

| Education | |

| College or university | 599 (59.7%) |

| High school or less | 265 (26.4%) |

| Postgraduate | 139 (13.9%) |

| Marital_status | |

| Free union | 37 (3.7%) |

| Married | 328 (32.7%) |

| Separated or widowed | 52 (5.2%) |

| Single | 586 (58.4%) |

| Employed | |

| No | 171 (17.0%) |

| Yes | 832 (83.0%) |

Bartlett's chi-square test 3571.53; df=15; p<0.01 and KMO=0.88. The communalities were observed between 0.45 and 0.753, and the factor loadings between 0.67and 0.86 (Table 2). A factor was retained, with an eigenvalue of 3.63 that explained 60% of the variance.

Communalities and loadings of the Fear of COVID-6 Scale.

| Item | Communality | Loadings |

|---|---|---|

| 1. It makes me uncomfortable to think about coronavirus-19 | 0.45 | 0.671 |

| 2. My hands become clammy when I think of coronavirus-19 | 0.59 | 0.768 |

| 3. I am afraid of losing my life because of coronavirus-19 | 0.479 | 0.692 |

| 4. When watching news and stories about coronavirus-19 on social media, I become nervous or anxious | 0.69 | 0.831 |

| 5. I cannot sleep because I am worrying about getting coronavirus-19 | 0.664 | 0.815 |

| 6. My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting coronavirus-19 | 0.753 | 0.868 |

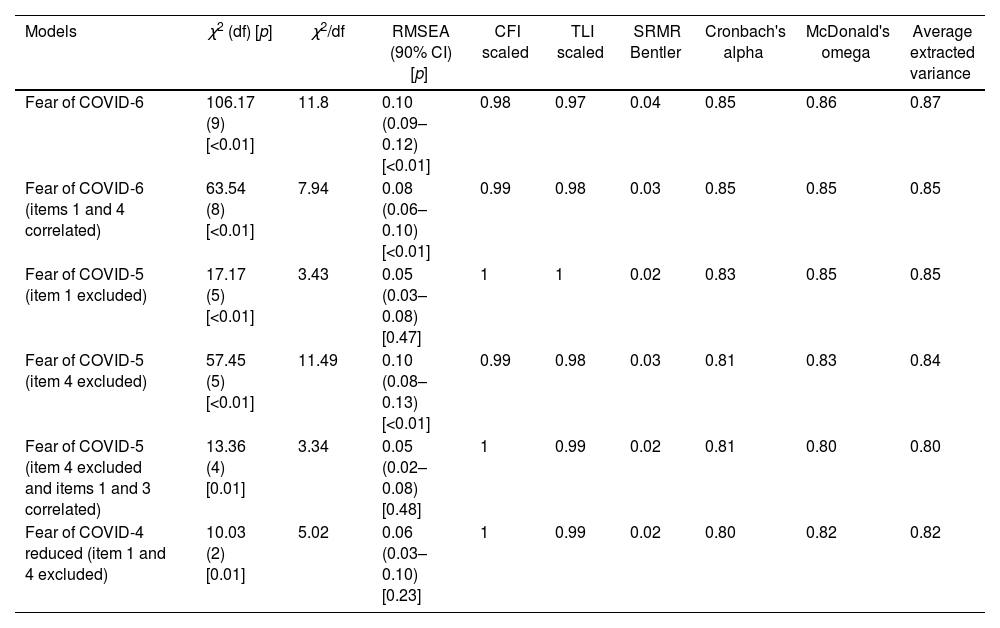

A CFA was made for, assuming a one-dimensional structure of six items. However, by virtue of the results, several alternative models were tested (Table 3).

Factor structure of various models of the Coronavirus Fear Scale.

| Models | χ2 (df) [p] | χ2/df | RMSEA (90% CI) [p] | CFI scaled | TLI scaled | SRMR Bentler | Cronbach's alpha | McDonald's omega | Average extracted variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of COVID-6 | 106.17 (9) [<0.01] | 11.8 | 0.10 (0.09–0.12) [<0.01] | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| Fear of COVID-6 (items 1 and 4 correlated) | 63.54 (8) [<0.01] | 7.94 | 0.08 (0.06–0.10) [<0.01] | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.03 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| Fear of COVID-5 (item 1 excluded) | 17.17 (5) [<0.01] | 3.43 | 0.05 (0.03–0.08) [0.47] | 1 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| Fear of COVID-5 (item 4 excluded) | 57.45 (5) [<0.01] | 11.49 | 0.10 (0.08–0.13) [<0.01] | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.03 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| Fear of COVID-5 (item 4 excluded and items 1 and 3 correlated) | 13.36 (4) [0.01] | 3.34 | 0.05 (0.02–0.08) [0.48] | 1 | 0.99 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Fear of COVID-4 reduced (item 1 and 4 excluded) | 10.03 (2) [0.01] | 5.02 | 0.06 (0.03–0.10) [0.23] | 1 | 0.99 | 0.02 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

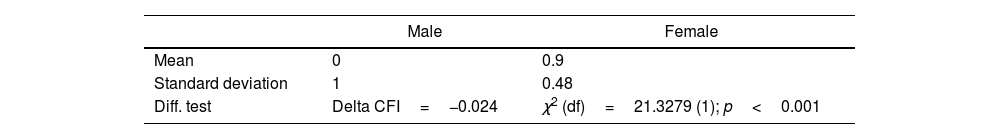

Gender invariance was observed at configural, metric (loadings), scalar (thresholds), and for latent means considering scaled chi-squared difference test with p<0.05 in all conditions and delta CFI <0.0. Fixing male latent mean as zero and comparing with female using a partial invariance model female had a 0.9 mean on Fear of COVID Scale (Tables 4 and 5).

Age and gender invariance of the FCV-5S.

| Models | χ2 (df) [p] | χ2/df | RMSEA (90% CI) [p] | CFI scaled | TLI scaled | SRMR Bentler | Cronbach's alpha) | McDonald's omega | Average extracted variance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |||||||

| Configural | 10.222 (10) [0.421] | 1 | 0.047 (0.018–0.076) [0.516] | 0.998 | 0.995 | 0.256 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| Loadings | 12.5 (14) [0.566] | 1 | 0.04 (0.011–0.065) [0.724] | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.244 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| Thresholds | 22.643 (23) [0.482] | 1.33 | 0.035 (0.01–0.055) [0.887] | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.265 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| Means | 207.146 (29) [<0,01] | 0.75 | 0.12 (0.106–0.134) [<0.01] | 0.958 | 0.971 | 0.026 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.81 | 0.86 |

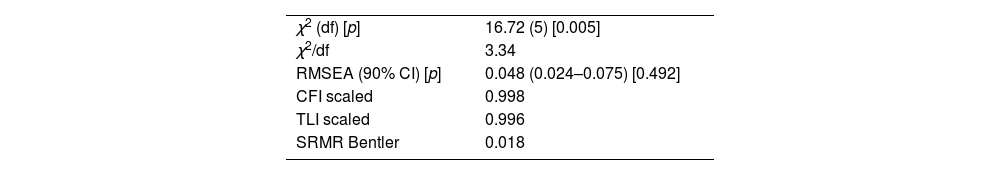

A mimic (multiple indicators and multiple causes) was used to check how age could influence in each item functioning. Good fit index was observed with CFI and TLI >0.99 (Table 6).

Same item's structure was kept with loading varying from 0.69 to 0.88. Even though age showed association with two items function (item 2 and item 4) with p<0.05 the standardized estimate was lower than −0.01.

DiscussionIn this investigation, new evidence was found in favor of fear COVID-6, it was observed that the six items version grouped a latent factor. From the AFE the fear COVID-6 grouped a latent factor, with an eigenvalue of 3.63 that explained 60% of the variance, which is consistent with a previous study in the general Colombian population.14 However, in the CFA phase the fear COVID-6 showed poor goodness-of-fit indicators, so it was necessary to evaluate several models where it was found that FCV-5S presented the best psychometric performance, a fact that reproduces previous results in Mexican, Argentinean, and Colombian populations.14,15,28 For this reason, several models were tested, of which the one with five items, was the one with the best fit indicators (subtracting the first “It makes me uncomfortable to think about COVID-19”). The 5-item version (FCV-5S) of the COVID-19 Fear Scale has better goodness of fit indicators than the 6-item version for a one-factor structure. FCV-5S accomplish with invariance by gender, partial invariance by age in the general population of Brazil.

The configuration of the 5-item version of the scale is justified by the fact that from the original FCV-19S study there was evidence of the problematic psychometric performance of the items 1 and 4 with lower factor loadings than the others,1 a situation that was confirmed in several studies such as in the Italian general population,12 and in Saudi Arabia.29 Interestingly, items 1 (“I am more afraid of coronavirus-19”), and item 4 (“When I see news and stories about coronavirus-19 on social networks, I get nervous or anxious”) also have a shared meaning compared to the rest, as they are general questions about the fear of COVID-19 or the feeling of discomfort when thinking about COVID-19.14 These findings suggest high local dependence, and covariation between items that could compromise the reliability of the scale.30,31

The FCV-5S showed invariance by gender at the configural, metric (loadings), scalar (thresholds), and for the latent means considering the scalar chi-squared difference test with p<0.05 in all conditions and delta CFI <0.0. Setting the male latent mean to zero and comparing it with the female latent mean using a partial invariance model, the female had a mean of 0.9 on the covariance fear scale.

The analysis of invariance in terms of internal validity as a requirement for a good instrument can be analyzed by considering only configurational invariance, loadings, and thresholds.32 When these levels of invariance are achieved, it is possible to compare the group means equally by comparing the latent means. In this case when the male latent mean was set to zero and compared to the female latent mean using a partial invariance model, the female had a mean of 0.9 on the scale, confirming gender invariance in this sample. On the contrary, FCV-5S showed lack of gender invariance in a general sample of the population of Peru and Argentina.15,33,34 On the other hand, analysis of a sample of 809 adults from the general population in Romania found invariance of scale items across gender groups through differential item functioning analysis and the graded response model (GRM).35 These differences in the level of invariance by gender in these studies could well be explained by the disproportionate distribution between men and women, conditions that are not suitable for conducting an invariance analysis.32

With regard to age, FCV-5S showed partial invariance, as items 2 and 4 are influenced by age, although the influence is small. Confirmatory factor analysis in this sample showed that the factor loadings and regression of each item by age yielded values in the regression coefficients that show how much age influences item response. This behavior was also observed in a study in Peru, where factorial invariance was found only for those over 40, but invariance between men and women was not met (ΔCFI=0.02) (ΔCFI=0.02).33

Implications for the public healthThis research focused on obtaining new evidence on the ability of a scale to measure fear of COVID-19. It is obvious that COVID-19 produces fear, however, its adequate measurement as a latent variable can help to understand the association with other matters of interest, such as compliance with health regulations, discrimination or the mental consequences derived from the pandemic.36,37

The FCV-5S can be considered to show good psychometric performance and may be useful for measuring fear of COVID-19 in the general population of Brazil. The short one-dimensional versions have the advantage that they evaluate the core aspects of the construct validly and reliably, require less time to complete, and can be used by people of all educational levels and income.16

Therefore, it can be recommended for use in large-scale epidemiological studies, studies evaluating the efficacy of psychological interventions, and to identify the presence of fear of COVID-19 in the population of Brazil. Studies proposed to evaluate analyses of invariance of this scale should adjust sample designs by sex and age to obtain reliable measures of the sex invariance of this instrument, especially in Latin American populations.

As stated before, the intention to achieve this scale is to have an adequate measure of fear of COVID-19 that can be associated with explanatory models of behavior around the pandemic. Previous experiences show that fear does not necessarily produce the best public health outcomes and that in some populations, such as adolescents, fear can be an attractive risk-taking factor.38 On the contrary, fear can produce inappropriate or unsustainable responses over time. Additionally, fear-based behavior change can produce counterproductive effects, such as distrust and confrontation with the authorities.39

LimitationsThe adequate sample size and the excellent process of linguistic adaptation of the scale are some of the strengths of the present study. However, the results of this study have to be analyzed in light of the following limitations. To assess the variable fear of coronavirus, a self-reported measure was used, which may be influenced by factors such as social desirability, recall bias and other common method biases.

In addition, test–retest reliability was not assessed to determine the stability of the scale over time. Another limitation has to do with the type of sampling. Because of the convenience sampling; this does not meet the characteristics of a random sampling, since the probability of participation in the survey is not known. Therefore, the sample is not considered to be representative of the general Brazilian population. The sample configuration represents a methodological limitation as the number of male participants may be so small that it does not meet the minimum conditions necessary for invariance analysis.32

Future researchIn accordance with the constraints, it is considered that, is considered that future studies should evaluate the reproducibility of the scale. In addition, studies using other methodologies are recommended (e.g., in-depth qualitative interviews, diary studies).

In order to gain further insight into the construct validity of the scale it is recommended to examine item performance with more robust models based on the item response theory.40

Future studies using nationally representative studies are needed to confirm the results reported here. From the previous annotations it is possible to carry out investigations with probabilistic population samples, to rule out biases related to the self-selection of those who make up the sample.

It is important to carry out other studies in which the fear of COVID-19 is associated with other latent variables, such as knowledge about the virus and the pandemic, beliefs regarding prevention, vaccination, as well as regarding the myths related to this public health emergency. This would allow us to know more about the nature of the measurement of COVID-19 and thus build a structure around the concept.

ConclusionsThe FCV-5S has a dimensional structure with partial invariance by gender and age and can be used to assess coronavirus fear in the general population in Brazil. More information on the psychometric properties of the scale could be gathered from these same applications.

FundingThis work was funded the researchers’ own resources.

Conflict of interestsThe authors do not have conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.