Anorexia nervosa poses an important bioethical dilemma, since patients often refuse treatment despite the danger that this poses to their health, and it is not clear that their decision is autonomous. The aim of this study was to investigate the perceptions/performance of psychiatrists and clinical psychologists regarding the capacity and involuntary hospitalisation of patients with anorexia nervosa.

MethodsSeven psychiatrists, four clinical psychologists, and one third-year resident psychologist were interviewed. A qualitative research approach based on grounded theory was used.

ResultsThe data analysis showed that these professionals articulate patient care around one main category - hospitalisation as a last resort and the search for voluntariness, which implies a change in the usual healthcare dynamics. Around this central category, some important concepts emerge: role stress, informal coercion, weight, family and chronicity.

ConclusionsIt is concluded that the difficulty of reconciling professional demands can undermine the quality of care and job satisfaction itself, which highlights the need for reflection and research into the foundations of the responsibilities assumed.

La anorexia nerviosa plantea un importante dilema bioético, ya que los pacientes, a menudo, rechazan el tratamiento a pesar del peligro que ello supone para su salud, y no está claro que su decisión sea autónoma. El objetivo de este trabajo es investigar las percepciones/actuación de psiquiatras y psicólogos clínicos ante la capacidad y el internamiento involuntario de pacientes con anorexia nerviosa.

MétodosSe entrevistó a 7 psiquiatras, 4 psicólogas clínicas y 1 psicóloga residente de tercer año. Se utilizó un enfoque de investigación cualitativa basado en la teoría fundamentada.

ResultadosEl análisis de datos mostró que estos profesionales articulan la atención del paciente en torno a una categoría principal, a saber, el internamiento como último recurso y la búsqueda de la voluntariedad, lo que implica un cambio en la dinámica asistencial habitual. En torno a esa categoría central, se erigen algunos conceptos importantes; estrés de rol, coerción informal, peso, familia y cronicidad.

ConclusionesSe concluye que la dificultad de conciliar demandas profesionales puede suponer un menoscabo en la calidad de la asistencia y en la propia satisfacción laboral, lo que pone en evidencia la necesidad de reflexionar e investigar sobre los fundamentos de las atribuciones asumidas.

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious disorder that has high morbidity1 and mortality2 rates. One of the characteristics of AN is that those who have it often refuse treatment, despite the danger that this poses to their health, and deny the problem or seem to struggle to grasp the severity of their situation. Thus, AN poses an important bioethical quandary as resistance to treatment may be inherent to the disorder and it is not clear whether the decision to refuse treatment is autonomous.

According to Spanish legislation,3 a patient has the right to make decisions that may seem absurd or risky to others, provided that the treating doctor deems them to be mentally competent. The law that specifically regulates involuntary commitment, Article 763 of Law 1/2000 on Civil Procedure4 (hereinafter Art. 763 LCP) is vague on its own application, requiring that individuals “not be in a position to decide for themselves”.

Evaluating the capacity of individuals with AN may be complicated since individuals are normally competent when it comes to making decisions on all aspects of their lives, with the exception of matters relating to their body weight, and they may have good results on standard competence tests.5,6

Incapacity is generally understood to be related to mental impairment, but it is not identified with such impairment. Therefore, in the validation study of the Spanish version of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T), 27.5% of psychiatric patients and 17.5% of internal medicine patients were deemed incapable.7

In Spain, the mental health specialist, i.e. the clinical psychologist or psychiatrist, is responsible for evaluating patients and processing the reports required to have them involuntarily committed due to mental illness.8

Studies have been performed on psychiatrists’ and psychologists’ attitudes towards the implementation of involuntary treatment9–11 and a few studies have been conducted on AN in particular.12,13

Tan et al.12 surveyed a group of general psychiatrists, child and adolescent psychiatrists and psychiatrists with experience in eating disorders. Survey respondents generally supported the suitability of involuntary treatment of patients with AN and believed that AN impairs treatment-based decision-making capacity and self-care behaviours. In the study by Jones et al.,13 psychiatrists also generally supported the role of compulsory measures in the treatment of patients with AN.

Nevertheless, on considering the knowledge of the authors as a whole, no research has been performed on how these professionals perceive and act in healthcare situations marked by the aforementioned elements, i.e. the situation of a patient with AN who still has capacity in many aspects but who rejects a treatment deemed to be necessary to safeguard their health or life.

ObjectiveThe objective of this study is to investigate the perceptions and behaviour of psychiatrists and clinical psychologists in the care of patients with AN who reject treatment when their physical health is at risk.

MethodsThe design of this study requires a qualitative research method using the grounded theory approach. The essence of grounded theory is to construct theory from data gathered and analysed systematically throughout the research process.14 With this methodology, data collection, analysis and, finally, theory are closely connected. However, there is no single universally accepted way to apply grounded theory.15,16 It is worth differentiating between the positivist paradigm and the constructivist paradigm. The first focuses on cancelling out any type of bias attributable to the researcher, while the second considers bias an integral part of the social world to be researched.17

A researcher who applies grounded theory generally does not start a project with a preconceived theory but, instead, tackles the project from a specific field of study and cannot erase from their mind all the theory they know before beginning their research.18,19 By interpreting the field of research in this “grounded” way, grounded theory has been applied.

ParticipantsUsing convenience sampling, a total of 7 psychiatrists, 4 clinical psychologists and 1 third-year resident psychologist participated. All of these, apart from 1 forensic psychiatrist and 2 psychiatrists who were experts in assessing capacity (understood as being specifically dedicated to this field or having produced scientific papers on the subject beyond the usual practice of psychiatry specialists), were experts in or worked at public facilities specialising in eating disorders (ED). The participants worked at establishments based in 5 provinces of Spain: Madrid (8), Ciudad Real (1), Albacete (1) Zaragoza (1) and Barcelona (1).

InstrumentsThe instrument used is a semi-structured, in-depth, individual interview based on a series of questions and topics prepared ad hoc from the script used by Sjöstrand et al.,20 adapted to research-specific objectives and healthcare circumstances in Spain.

The interview script was organised into the following content groups: a) legislation governing involuntary commitment and patient autonomy; b) usual clinical practice if a patient with AN refuses treatment; and c) conceptions of AN patient competence, and reasoning and experience concerning decisions about involuntary treatment.

ProceduresSemi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face (7) or by email (1) with the participants living in Madrid. All other interviews were conducted over the phone due to a lack of resources. With the exception of the interview conducted in writing by email, all interviews were recorded using a SONY ICD-PX370 voice recorder.

The interviews were transcribed and their content was analysed using the sequence proposed by Corbin et al.,14 adapted to the study objectives. QDA Miner Lite software was used to help with the analysis. The analysis process involved reading and re-reading the texts, with coding and re-coding according to text segments identifying an idea, to generate categories and their properties and then determine how the categories vary dimensionally. From the readings, coding and re-coding, categories emerged that were developed systematically and linked with sub-categories, which in turn allowed the initial codes to be re-coded in an iterative cleaning process. The categories increased in content density with the development of properties and dimensions until the point of theoretical saturation was finally reached, at which time the analysis of new information offered no new properties, dimensions or relationships. Categories were integrated and refined to expand the set of theory knowledge. As a result of the above, and especially memos, the analysis was completed, offering an explanatory structure around a core (central) category.

Attempts were made to guarantee the accuracy of the research by using the following essential components of grounded theory. The iterative data analysis occurred at the same time as data collection. Participants were deliberately selected afterwards for interviewing based on the analysis and emergent findings. Memos of preliminary findings were kept throughout the research process for use as building blocks of the new theory. Finally, checks to guarantee accurate data interpretation were performed in 3 ways: accuracy of understanding was verified throughout the interviews with the participants, initial interview results were validated with subsequent interviews, and a joint analysis was performed by both a male and female researcher not involved in prior steps as a triangulation method to verify the explanatory viability of the core category reached, until integrated, reduced and refined around an axis.

Ethical considerationsParticipants were informed of the purpose, procedure and expected benefits of the research prior to enrolment. They were also informed of guaranteed confidentiality and their entitlement to withdraw from the study and that, in the event of withdrawal, all recordings and transcriptions would be destroyed. An information leaflet was provided containing an example of an informed consent form signed by the researcher.

In fact, in order to ensure confidentiality and considering the method of contact with some participants, the extracts presented in this article only refer to participants by number, profession and whether they are ED specialists.

ResultsThe data analysis resulted in a core category that shows that psychiatrists and clinical psychologists express the need for care based around striving for voluntary acceptance of commitment when the patient’s physical health begins to be concerning, and involuntary commitment is only used as a last resort. This implies a change in the usual healthcare dynamics to find the situation where the patient’s physical health is less dire. Some important concepts emerge around this core category: role/organizational stress (cause of change), informal coercion (mechanism of change), body weight (trigger of change) and family and chronicity (decision modifiers).

Main category: last resort/striving for willingnessThe main idea brought out by psychiatrists and psychologists in almost all the interviews is that involuntary intervention must be the last resort in AN. For most participants, involuntary commitment is not desirable and is generally only advisable when the motive is to protect the patient’s life. The reason for avoiding involuntary commitment is based on 3 main aspects: it casts serious doubts on respect for the patient’s autonomy, it has a negative impact on the working alliance and, in many cases, it is ineffective in the long term.

“Involuntary admission is the option that generates the most stress in the delicate thread holding the therapeutic relationship together and it is only used in those cases where we believe there is a risk to the patient’s life” (Participant 1, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

“Here, we always, always try to get the patient to make the decision to be admitted voluntarily” (Participant 5, psychologist specialising in ED).

“Normally, and sometimes in a high percentage, involuntary admissions leave and do the same thing again. We prefer it if admission is voluntary” (Participant 9, psychologist specialising in ED).

For some professionals, involuntary commitment is delayed as much as possible, even if it means accepting a certain level of risk to the patient’s physical health. “It is always better to have the patient’s cooperation in eating disorders. And therefore, I generally tend to risk a lot. So if I admit a patient it is because I have no other choice and we can’t risk that the patient die or have a serious complication” (Participant 10, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

This does not change the fact that early intervention is desirable. “The longer you take to decide they need admitting, the worse it is for the patient. Because things will go backwards. That is what almost always happens. There may be the odd case, but not many. Because it is very hard to recover if you are very low” (Participant 3, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

Be that as it may, the result of striving for willingness does not always go the way you hoped and it may be necessary to resort to involuntary commitment in the end. “Look, since things are not always simple, you have to risk it a bit in the sense of the bond and all that with the patient. Because you knew this patient was going to be admitted, but you tried to get them to accept it in a way that was more pleasant for the patient. You haven’t managed this, for whatever reason, maybe because you haven’t explained things well or you should have gone straight to involuntary admission… maybe you didn’t know early enough how to suggest things in a more appropriate manner and therefore you didn’t achieve voluntary admission and you need to change things up because, in your opinion, you cannot discharge them” (Participant 4, psychologist specialising in ED).

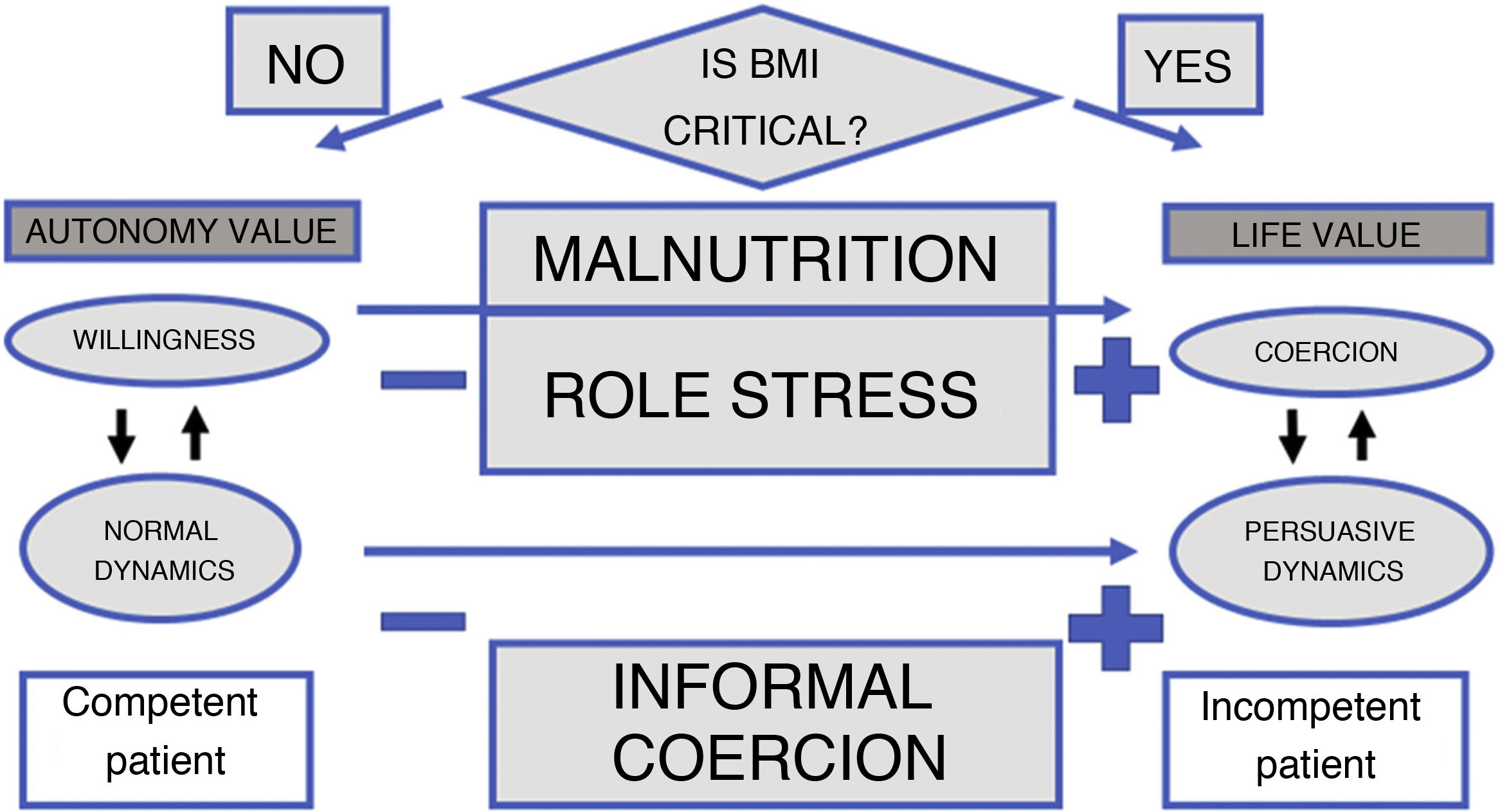

Change of dynamics (consequence)The therapeutic relationship in AN is conditioned by the patient’s physical circumstances and two different types of healthcare dynamics can be distinguished (Fig. 1):

- 1

Normal dynamics, patient focused: if the patient has a body weight that is not critical, that is acceptable, that does not cause the professional to suggest the need for urgent intervention, the therapeutic relationship is conventional and the professional relates to the patient in a way that is less coercive, aimed more at getting to the bottom of the problem than at tackling the physical urgency of the case. Patient autonomy is the priority. The professional is relatively comfortable with patient autonomy since the objective is to achieve an improvement that does not generate a life-threatening emergency and, therefore, does not raise the need for an involuntary intervention. The patient is normally deemed competent.

- 2

Persuasive dynamics, aimed at convincing the patient: when the patient starts to get close to a body weight or body mass index (or other indicators, such as kalaemia, etc.) that clearly put the patient’s physical health at risk, the professional starts to experience some role stress as, on the one hand, he/she must continue to act in such a way as to respect patient autonomy and take care of the therapeutic relationship, but at the same time has a duty of care and even the perceived duty of imposing unwanted care. Life is the number one factor. The professional is in a less comfortable situation, exacerbated by being aware of the possibility of psychological ineffectiveness of the intervention and the damage it may cause to the interpersonal relationship and healing. In this situation, forms of informal coercion may be used to make the patient accept commitment. The patient is deemed incompetent.

Physical deterioration of the patient places challenging demands on psychiatrists and psychologists. Respect for the patient’s decision (autonomy) is complicated by: the obligation to reverse the patient’s physical deterioration if the patient is deemed to not be competent. “… I have an ethical and legal obligation to protect and take care of you, even if you are not competent to do this yourself” (Participant 10, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

In other words, professionals must respect the patient’s decision but, at the same time, try to get them to receive a treatment that they reject. They describe this as difficult, complex, subjective, etc. “… I am aware that you must be very respectful of the patient’s autonomy but this, especially with patients with ED, is sometimes very difficult” (Participant 12, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

“It is something that is very complicated to resolve. It is also not at all scientific either, or anything that you can explain in simple terms, and you need to assess so many areas that go beyond medical criteria, you need to assess many areas because a great many factors play a role in people’s lives, apart from our physiology and our body, many factors that are no less important than others and you have to explore them all. And with all of this, in the end you make a decision, a decision that is ultimately subjective in the end” (Participant 4, psychologist specialising in ED).

Such demands pose different levels of difficulty. On the one hand, patients with AN have some special characteristics that make the therapeutic process more difficult. “Interpersonal distrust is very important. So these are aspects that would be difficult in any patient. The thing is that in patients with ED, this is quite normal, like everyday functioning” (Participant 9, psychologist specialising in ED).

On the other hand, ordering involuntary commitment requires that the patient’s lack of capacity first be determined since it would not be legally possible if the patient were deemed competent for making decisions. Nevertheless, it is not easy to assess capacity in patients with AN. “I think that, in other cases, you probably don’t have as many questions in your mind when it comes to assessing capacity, but I think that in these people, many more doubts may arise because I think they are somewhat more capable of creating a very logical and well-constructed argument to explain their decisions to you, their decision to not eat or adopt certain behaviours, or whatever. So I think this may pose more problems, yes” (Participant 8, general psychiatrist). “If we all have that doubt, it is because there is of course some level of competence, right? Because if you clearly think a patient is incompetent, why does a doctor who can see that a person has no cognitive capacity to make decisions decide not to admit such a person? In other words, if I admit patients with other diseases so calmly, why don’t I with this disease?” (Participant 2, general psychiatrist).

A patient is normally deemed competent to make decisions. And this capacity is usually identified with the desire to be healed and willingness. “Most people with ED are of course competent to decide on their care. All patients visiting our centre do so voluntarily…” (Participant 1, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

However, not even this conception of the patient is unanimous. “I have had patients with anorexia with a very good knowledge of the disease, good mental capacity and good awareness of the risk they were taking, but that is not the norm. It is not usually like this. But there are a few” (Participant 12, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

This poses a difficulty when it comes to deciding on involuntary commitment and it means that the final criterion for admission is physical risk. “…Actually, whenever involuntary admission is ordered, it is not due to a mental cognitive condition, but rather to the physical condition. It is ordered when that minimum BMI limit that is life-threatening has been exceeded. It is a matter of life or death, the patient’s living condition, since the patient cannot, of course, continue to not eat and we are going to force them to eat, even if this is via a nasogastric or intravenous tube, because there are even people who refuse to drink water, and it is this situation that results in involuntary commitment” (Participant 2, general psychiatrist). “But normally the difference that may exist between another psychotic episode or another type of problem that results in them being admitted to psychiatric units tends to be due to the physical and medical risk to their life. This is what is at stake, this is what is at risk” (Participant 9, psychologist specialising in ED).

Moreover, although the patient is deemed incapable, taking involuntary measures that are rejected by the patient may cause extreme harm to the therapeutic relationship and, consequently, recovery in the long term. “Even then it is a very complex situation because, potentially in the short term, if there is an imminent risk to the patient’s life, I believe the patient then does not have the capacity to decide and we, as professionals, have to make the decision, for involuntary admission or whatever. But it is true that this has implications for the therapeutic process and it is necessary to see how this is handled with the patient” (Participant 5, psychologist specialising in ED).

Informal coercion (mechanism of change)Attempts to achieve voluntary acceptance of commitment are made through mechanisms of informal coercion, which arise less frequently in situations where the patient’s physical health is not at risk. Participants are aware that, within the range of possible interactions, not everything is permitted. “So we must not manipulate or coerce, but we can influence and condition; in fact, it is part of our job” (Participant 8, general psychiatrist). “Of course we have the right, the obligation to try and persuade them. We are here to help patients (…). But by persuading them, not forcing them, by respecting their autonomy, respecting their autonomous decision regarding the right that every human has” (Participant 11, general psychiatrist).

Nevertheless, the limits between coercion and legitimate persuasion are not always easy to establish and types of relationship that even the participants consider questionable sometimes enter into play. “I mean that the line with coercion is sometimes blurred. And we, even the young doctors, are still used, even to a paternalist point, to saying I know what is best for you. And based on this, on the fact that I know what is best for you, I force you to a certain point, or I try to oblige you or to push you and not to convince you to do something” (Participant 12, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

In some cases, coercion even reaches the point of becoming institutionalised, in the sense that it governs the operating procedures of healthcare facilities. “I actually know that almost all wards adopt a reward-based system: if you meet your goals, you gain weight, you take your prescribed rests or other things or allow the tube to be inserted or whatever, then you get rewards, you can go out to have a smoke, your parents can come to visit you, you get permission to go home at the weekend… If you don’t comply, then we will take things away” (Participant 5, psychologist specialising in ED).

If efforts of persuasion are not enough, then involuntary intervention is chosen. The basic reasons for this are fundamentally to safeguard the patient’s life and, to a lesser extent, to restore autonomy and to focus on early interventions in AN. “As I have already said, when doctors are faced with a situation of a borderline BMI, the situation is probably also fairly clear - it is borderline - there is a risk of death so we are going to admit the patient. Even if that admission is only to increase the BMI and is in no way going to change everything else causing the symptoms or clinical status. It is simply to get you away from that level of risk to your life” (Participant 2, general psychiatrist).

Body weight (trigger of change)As observed, indicators that are not strictly psychopathological, especially body weight or BMI, are of great importance. Body weight is established as a category with attributes that go beyond the physical magnitude. Body weight triggers the alarm signal. “…Whenever involuntary admission is ordered, it is not due to a mental cognitive condition, but rather to the physical condition. It is ordered when that minimum BMI limit that is life-threatening has been exceeded” (Participant 2, general psychiatrist).

It is related to the patient’s decision-making capacity. Body weight (or BMI) is one of the key elements affecting the decision to admit the patient and its importance is justified by the effects of malnutrition on mental processes. “Capacity is related to weight loss insofar as weight loss organically produces an obsession for weight and food” (Participant 1, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

Visibility is an important feature in AN. “Until that emaciated state becomes so evident that you can see it and you can’t avoid seeing it” (Participant 2, general psychiatrist).

Chronicity (decision modifier)Participants find differences between the quality of decisions made by first-time and chronic patients. “After 10 years of the disease, the patient has learned and has even been able to learn to be aware of the disease and that there are certain symptoms that the patient has and recognises they have. The key is to go patient by patient; to assess that patient’s individual case. It is not the same at the beginning as 10 years on. And understanding, appreciation and reasoning will be different because the patient has learned to reason” (Participant 11, general psychiatrist).

Although predominant, acceptance of the improved decision-making quality of chronic patients is not unanimous. “My experience is that the capacity to be able to decide is generally much more involved in chronic patients. Perhaps due to their severity, perhaps because the most serious patients become chronic, because chronic patients are precisely the ones who have more difficulties in this sense” (Participant 12, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

Nevertheless, this does seem to support the idea that involuntary commitment in chronic patients is less suitable given the limited hope of success. “An 18-year-old patient who has recently been diagnosed with AN and who can dream of being cured because he has only had the disease for 6 months if admission is involuntary and I force him to eat and reach a healthy weight is not the same as a patient who has had the disease for 20 years and for whom I already know that dreams of a cure are very unlikely” (Participant 12, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

For chronic patients, it is accepted that there may be treatment objectives that are more unobtrusive and more in line with the patient’s preferences. “In more chronic patients, your aim is perhaps to reduce harm, which is not as much their recovery as ensuring that the patient has a sufficiently adequate life” (Participant 5, psychologist specialising in ED).

Family (decision modifier)Family is a category of extraordinary importance as it arises systematically without being mentioned by the interviewer. Family can become a de facto decision maker: “…what sometimes, often, encourages admission is family pressure” (Participant 2, general psychiatrist).

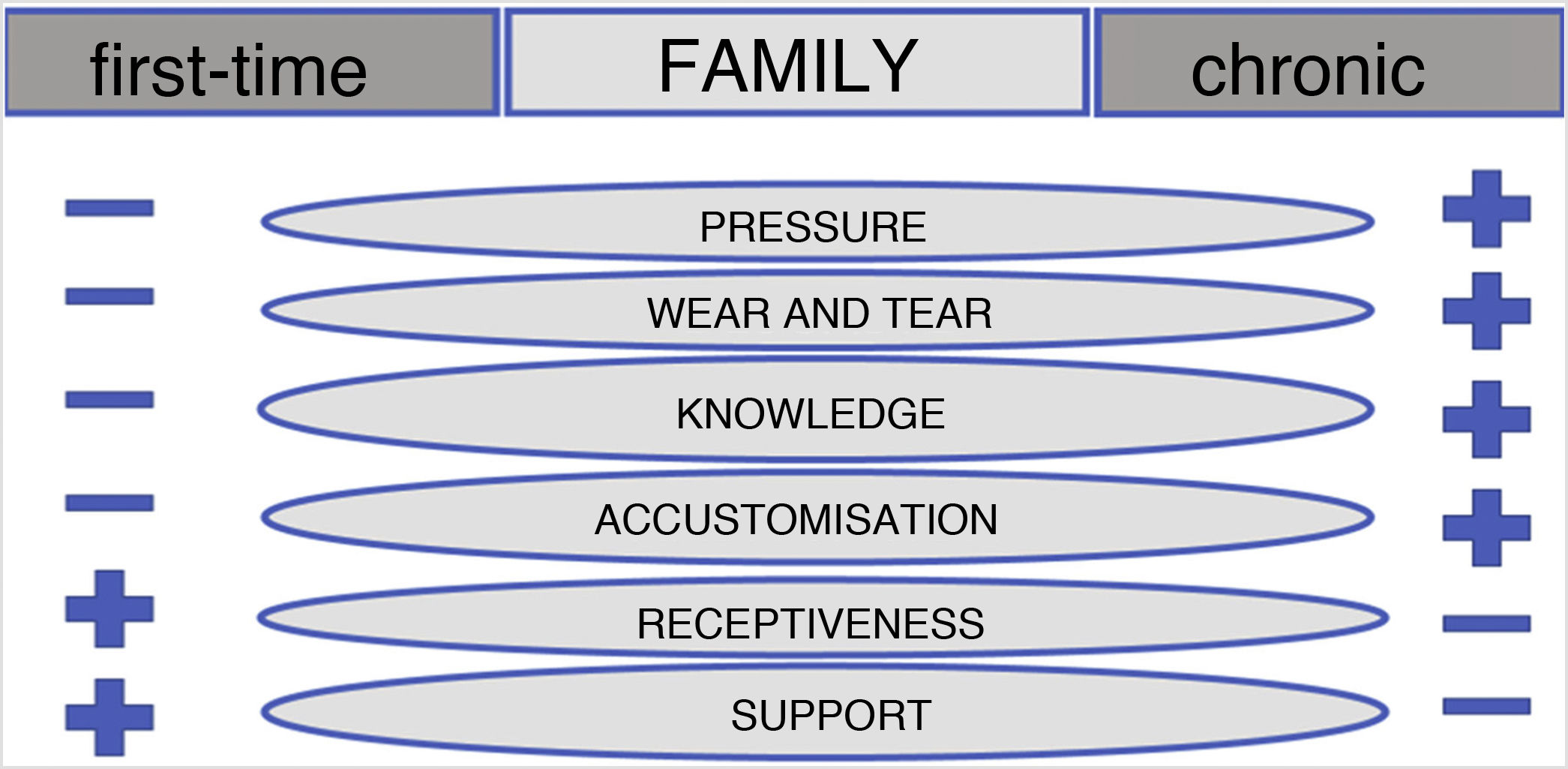

In this context, family presents a series of properties with different dimensions, which will allow us to differentiate between two types of family, first-time or chronic, in relation to the type of patient, first-time or chronic (Fig. 2).

The families of chronic patients put more pressure on the healthcare professional, partly thanks to their better overall knowledge (of the disorder, of the different healthcare facilities, of the influence of the pressure they exert, etc.) and also as a result of the increased wear and tear that the many years of disease have had on them. Their level of patient support is lower, as is their receptiveness of medical indications. It is possible that they have become used to the disorder, which may reduce their ability to detect warning signs. The families of first-time patients tend to act in the opposite manner.

DiscussionThe objective of this study was to investigate how psychiatrists and clinical psychologists perceive and manage care when patients with AN reject treatment and this puts their physical health at risk.

The results show that these professionals face serious difficulties when performing their professional duties. Objectives that are sometimes incompatible (healthcare and respect for patient autonomy) lead to the concept of role stress.21,22

It is important that professionals consider the ultimate cause of such opposing demands and whether this situation is avoidable. The ultimate root can be found in the fact that part of this discussion is outside the scope of science and is related more to the scope of ethics. Professionals find themselves in a situation where they are required to make decisions outside their technical ability. And although this dates back to days of old, it has perhaps become a relic that is incompatible with modern-day autonomist legislation.

It seems evident that the difficulties faced by the participants may be reduced if their mission were the simple dispensation of technical care, more akin to that offered by specialists not practising within the scope of mental health. Medical staff are trained to diagnose and assess the type of treatment available to the patient. But the decision or infliction of treatment options goes far beyond such training.

Let’s stop on this idea. The ethical attribution poses an obstacle to the normal course of the therapy and produces a change in dynamics that may prevent true therapeutic progress by making the basic aim of therapy to convince the patient. We must not overlook the fact that this product of adequate therapy and perhaps as a result of greater awareness of the disease, it may finally be decided to follow the treatment option that includes commitment, with which the professional’s actions are aimed at bending their resistance.

It would be different if an adequate nutritional condition were deemed necessary to achieve reversal of the psychopathological state. This idea is acceptable but invalidates the option to postpone involuntary treatment until the patient’s life is at risk and instead requires early implementation of such treatment. In fact, some authors warn that delaying commitment could become a double-edged sword if it helps turn the disorder into a chronic condition.23

We must not forget the patient’s possible lack of capacity. If this were determinable, which raises questions,5,6,24,25 and there were proof of the patient’s incapacity, it would be necessary to determine whether there is a more appropriate decision maker than the patient themselves23 and whether this should necessarily be the treating doctor. De Miguel26 believes that a request by the doctor to commit a patient is not only illegal (this should be the decision of the healthcare facility’s director) but also immoral (the doctor should not be involved in decisions that undermine his/her legitimate trust with the patient).

To answer the question of whether a type of care that allows psychologists and psychiatrists to focus exclusively on tackling the psychopathological problem and not be constrained by other matters is a good idea, it may be appropriate to once again compare their role with that of other healthcare professionals outside the field of mental health. Any patient would reject the care of a healthcare professional who is trying to convince or force them to be committed. And if the professional believes that, after such rejection, a patient can hide his/her incapacity, the best thing would be to ask mental health specialists to evaluate the patient’s capacity. Although it is sometimes thought that such justification can only be made by mental health professionals due to their increased evaluative knowledge, the importance of safeguarding the therapeutic relationship by referring this mission to another professional must not be overlooked.

A similar mechanism could perhaps be used in mental health to improve the doctor-patient relationship. This makes perfect sense since, as already mentioned, incapacity is related to, but not identified with mental impairment.7

It is also important not to forget that these patients evoke particularly intense countertransference reactions.27 Professionals are not immune to such reactions and a common countertransference response is to react with coercion and control.28–30

If another professional were to evaluate the patient’s capacity, the change in healthcare dynamics may not be so apparent since the professional stress situation would be reduced as a result of not adding a new mission that is hard to reconcile. If the patient is competent, the decision is their own to make. If the patient is not competent, involuntary commitment should be assessed. And this leads us to another debate - who should decide? And even who should decide who should decide?

Informal coercionOur finding that informal coercion is used is consistent with earlier publications. For García,31 informal coercion is present in all of the countries studied (including Mexico and Spain) and in all of its evaluated forms (persuasion, interpersonal influence, inducement and threat), but also in other modes (deceit, blackmail or leading attitude). It seems that the disapproval of informal coercion in theory is overridden in psychiatric practice.32

The infrequent use of formal legal compulsion is based on lesser coercive tactics that are used ubiquitously to control treatment resistance in patients with eating disorders.33 The fact that the procedure outlined in Art. 763 LCP is not used does not mean that commitment represents the patient’s free decision. Some extracts support this. “In other words, she accepts it, she accepts it, but don’t leave me alone for long, because I have only agreed because you have manipulated me and I see that I don’t have a choice” (Participant 7, psychologist specialising in ED).

Without going into the suitability of admission, it seems inappropriate to label these ways of agreeing to commitment as voluntary. The literature mentions this and discusses to what extent the line between coercion and excessive leverage and social pressure may become blurred. For example, in the MacArthur Coercion Study involving psychiatric patients, 40% of the patients admitted voluntarily said that they believed they would have been involuntarily committed if they had rejected voluntary admission.34

CapacityIt has been shown that one of the difficulties experienced by psychologists and psychiatrists is the complexity of the requirement to evaluate the capacity of patients with AN. The literature warns us of this complexity. (Lack of) appreciation is the most important element to consider when evaluating capacity in anorexia nervosa.6 The patient may understand and process the medical information but may not be able to associate it with him/herself. The difficulty lies in the fact that standard capacity criteria do not reflect difficulties that are truly relevant in treatment rejection by AN patients, especially some values that seem to be determined by the disorder itself.5 However, deciding which values are or are not valid would in itself introduce a subjective and morally complex element into the assessment of mental capacity.6

Disease awareness is also a very complex concept.35,36 Arbel et al.37 understand that disease awareness in AN is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon or a unitary concept but rather a melting-pot of superimposed dimensions or awareness systems, ranging from awareness of having a mental disease and its consequences to the delusional idea surrounding body image. Therefore, the assessment of capacity in dichotomous terms is perhaps a fantasy.

Despite everything, lack of disease awareness or appreciation are often used as an argument to justify involuntary commitments. In reality, a lack of awareness or appreciation does not medically justify any intervention on a person opposed to that intervention. It only describes a certain amount of difficulty recognising the disease itself.

Willingness and the conception of patient autonomy may be related in a peculiar manner that must be taken into consideration. Some professionals tend to identify competence with willingness or a desire to be healed. Kendall38 warns us of this risk, i.e. the possibility of confusing the patient’s attempts to make decisions that deviate from the treatment plan with evidence that the patient is controlled by the AN and cannot make treatment decisions in an autonomous, competent manner, which then justifies paternalism. However, acceptance does not indicate capacity in the same way as rejection does not indicate incapacity, although, in cases of risk to the patient’s health, this may be a warning sign suggesting the need for assessment.39

Confusing willingness with competence also results in a specific use of Art. 763 LCP. “Voluntary-involuntary” in the mind of healthcare personnel is sometimes interpreted as “without opposition-with opposition”. The legal interpretation establishes that involuntary commitment is due to the patient’s lack of capacity to make decisions, regardless of whether the patient opposes admission.40,41 Nevertheless, even when legal control seems to be necessary, it is also true that the legal procedure that this entails is not without its faults from a therapeutic point of view. This aspect should perhaps be considered for future research.

Body weightBody weight is an element that the participants systematically associate with capacity. In effect, the research warns us of various behavioural and neuropsychological disorders related to being underweight. However, it is important to be somewhat cautious when considering how this relationship works. It seems that the consequences of starvation explain behaviours of binge-eating42 and that the relationship between insight and BMI may no longer be significant when possible confounding factors are controlled.36

Linking malnutrition with capacity raises two different, but closely related key issues. The first is, why does a well-nourished brain stop eating? The second is based on why a behaviour is justified by the lack of nutrients if such deficit is not present in the beginning. The fundamental aspect lies in the fact that passing a given BMI threshold is not proof of incapacity.43

From this, we can deduce that since involuntary commitment is considered as a last resort, this implies that a lack of capacity is present before making this decision and that a life-threatening criterion simply has to be exceeded to make the involuntary intervention more legitimate. Although the idea that weight loss affects capacity is accepted, this discourse cannot be contaminated with the false belief that capacity is lost as a result of exceeding a given BMI threshold.6 Obviously this does not prevent capacity assessments from being performed at different times, as capacity “is defined for a given moment and a specific task”.39

As we have seen, one characteristic of body weight is its visibility. One hypothetical consequence of this visibility is the possibility of a “horns” effect,44 which is understood to be the negative impact of one characteristic on the assessment of another unrelated characteristic (capacity in this case), which leads us to consider that the patient is less competent than he/she really is: “Because how can you think you are fat when you are clearly just skin and bones? How? But they feel fat. And yes, of course they develop behaviours that, let me reiterate, as you say, they can’t be right in the head, right?” (Participant 2, general psychiatrist).

Potential research on this matter is suggested.

Family and chronicityThe importance of family is consistent with the robust references to this in the literature.45,46 Family may help enormously in the therapeutic process but it may also apply pressure that makes the psychiatrist or psychologist’s professional activity more difficult. It is worth noting that some of this pressure could be reduced if the family were relieved of the burden of having to make decisions regarding involuntary interventions.

With regards to chronicity, particular sensitivity towards the implementation of involuntary interventions in patients who have been suffering for many years has been observed among participants. This may help avoid therapeutic futility or obstinacy. In this sense, limited hopes of success are a key element. Regarding capacity, some interventions remind us of those kinds of transcending functions of the self that Yager47 speaks of or the notion of life awareness with disease,23 which seem to give a better quality to the chronic patient’s decision.

Is it impossible to apply principles of bioethics?Everything said so far seems, to some extent, to support recent publications by authors such as Giordano,25 in the sense that the exceptional circumstances characterising AN provide moral reasons for partially overriding customary principles for making ethical decisions. This author states that coercive treatment in patients with chronic anorexia must be limited due to the limited hopes of success and the view that early paternalist intervention may be more justifiable, ethically speaking, than later coercive intervention.

Cognitive dissonanceThe potential use of both formal involuntary actions and unwanted mechanisms of informal coercion lead to decisions that cause unease in healthcare professionals. “Using a nasogastric tube is horrible. But the thing is it must sometimes come to that or the patient will die” (Participant 7, psychologist specialising in ED).

It is worth investigating whether this could give way to mechanisms promoting reduction of cognitive dissonance48 due to the similarity with the circumstances that the literature reports as conducive to this.49,50

One potential undesirable consequence would be if, after choosing the option of involuntary commitment, with all the emotional burden that this entails, the professional decided to continue with this type of action in order to blindly adapt his/her care to information supporting such actions, thereby reducing the professional’s unease.

Some extracts suggest the possibility that mechanisms promoting reduction of cognitive dissonance may be in use. Let’s look at an interpretation of three fragments; the sole purpose of this interpretation is to encourage reflection and, if applicable, to sow a seed for future research, but under no circumstances is it to be used as evidence.

Normalisation of the deviant situation. A situation that appears to deviate from the most desirable situation is taken as being normal. “The thing is that we always generally try to make the patient accept it voluntarily. Of course they don’t say to you ‘yes I want to’” (Participant 7, psychologist specialising in ED).

Harmonious interpretation of the demand. The patient’s demand is interpreted in such a way as to not generate unease, even if this implies distancing yourself from the literal sense of the words. “…I interpret it (rejection) more as a way of asking for help rather than as actual conviction” (Participant 10, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

Justification. Attempts are made to find elements that reinforce the idea of the need to act in the way in which they were trained. “…Coercion, well sometimes you have no other choice” (Participant 12, psychiatrist specialising in ED).

ConclusionsThis study shows that psychiatrists and clinical psychologists are subject to demands that can be difficult to reconcile when the physical health of a patient with anorexia nervosa deteriorates. This forces them to change the usual therapeutic dynamics to try and reconcile such demands in the best way possible. This shows the need to reflect on and investigate the basis for any attributions assumed, alternatives, if applicable, and effects that this may have on the patient’s care and on the healthcare personnel’s work satisfaction.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.