The Patient Health Questionnaire (Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9]) is a 9-item instrument designed to screen for major depressive episode in the past 2 weeks according to the criteria of the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual.1 The PHQ-9 is popular because countless research studies have tested its psychometric performance in different populations.2,3

In Colombia, compared to a structured clinical interview, the PHQ-9 showed a sensitivity of 90.4% and a specificity of 81.7% in primary care consultants with a cut-off point of ≥7.4 A two-dimensional factor structure was observed for the PHQ-9, which adequately adjusted to the data of university students studying health sciences. The first factor (non-somatic symptoms) brought together items 1, 2, 6 and 9 and the second (somatic symptoms), items 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8.5 Lastly, the PHQ-9 has shown high internal consistency, with Cronbach's alpha values between 0.80 and 0.83.4,6

Psychometric performance is highly variable between different samples of participants, meaning that adequate psychometric properties of a scale in one group do not guarantee the same performance in another with different social and cultural characteristics; this, therefore, calls for validation studies to be carried out in dissimilar contexts, to obtain comparable and acceptable behaviour.7

Validation of instruments is only an illusion because it is generally statistical or inferential. Psychometric indicators are not “properties” of the measurement scales, but rather reflect only the response pattern of the participants.7 The cut-off points to define cases must always be determined for each population.8 The factor structure can show different numbers of factors.9 Moreover, the observed internal consistency of the scales is usually more stable than the cut-off point and the factor structure. However, it is the least reliable and accurate indicator of reliability and validity.10 Internal consistency is very sensitive to the number of items and response options and must also be calculated separately for each factor of a bidimensional or multidimensional scale.11 Calculating internal consistency is a relatively more straightforward, simpler and cheaper process than estimating the number of factors or the best cut-off point for a population. This is why internal consistency is sometimes reported in scientific publications as an indicator of validity and reliability.12

Given the need to quickly have validity and reliability indicators of the PHQ-9 in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic to screen for a major depressive episode in different contexts, this study aimed to perform a factor analysis and calculate the internal consistency of PHQ-9 in COVID-19 survivors in Santa Marta, Colombia.

We had the participation of 330 COVID-19 survivors, aged from 18 to 89 (mean, 47.7 ± 15.2 years); 61.5% were female; 62.4% had a university education; 66.1% were married or in a long-term relationship and 71.2% had low family income. Participants completed the PHQ-9 online. Each item offers four response options which are scored from 0 to 3; the higher the score, the greater the risk of depression.1 Exploratory factor analyses (EFA) and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were performed and Cronbach's alpha was calculated.13 The analysis was performed with the Jamovi 1.8.2 program. This study was approved by an independent ethics committee (Minute 002 of the ordinary meeting, 26 March 2020).

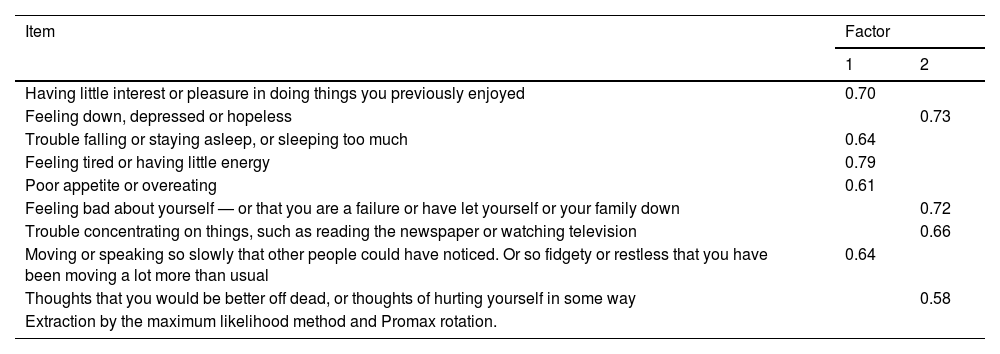

The EFA showed KMO coefficient = 0.86; Bartlett's χ2 = 3,985.3 (df = 54; p < 0.001) and two factors: factor 1 (non-somatic) (items 1, 3, 4, 5 and 8) with an eigenvalue of 4.2 (46.3% of the variance), and factor 2 (somatic) (items 2, 6, 7 and 9) with an eigenvalue of 1.1 (12.5% of the variance). The correlation between the factors was 0.59. The CFA confirmed the adequate two-dimensional structure: Satorra-Bentler χ2 = 97.1; gl = 26; p < 0.001; χ2/df, 3.8, RMSEA = 0.09 (90% confidence interval, 0.07−0.11), CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.90 and SRMR = 0.05. The PHQ-9 showed α = 0.85; factor 1, α = 0.81, and factor 2, α = 0.75. Table 1 shows the factor loadings.

Factor loadings of the PHQ-9 in COVID-19 survivors.

| Item | Factor | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Having little interest or pleasure in doing things you previously enjoyed | 0.70 | |

| Feeling down, depressed or hopeless | 0.73 | |

| Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | 0.64 | |

| Feeling tired or having little energy | 0.79 | |

| Poor appetite or overeating | 0.61 | |

| Feeling bad about yourself — or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down | 0.72 | |

| Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | 0.66 | |

| Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed. Or so fidgety or restless that you have been moving a lot more than usual | 0.64 | |

| Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or thoughts of hurting yourself in some way | 0.58 | |

| Extraction by the maximum likelihood method and Promax rotation. | ||

The PHQ-9 presented a two-dimensional structure, as reported by Cassiani Miranda et al.5 However, there were differences in the items retained from each dimension. The internal consistency of the PHQ-9 was similar to that previously reported.4,6 The goodness-of-fit indicators of the CFA and Cronbach's alpha are acceptable parameters of validity and reliability of the PHQ-9.10,11,14 However, it is necessary to establish the best cut-off point for a major depressive episode in COVID-19 survivors.8 The "validation" of measurement instruments in psychiatry is an endless process, which is repeated and has to be corroborated each time the instrument is applied to a particular sample.7 Provisionally, the PHQ-9 can be used to screen for depression, given the high frequency of depression observed among COVID-19 survivors,15 thereby reducing the likelihood of worsening or chronicity.16

In conclusion, the PHQ-9 shows a two-dimensional structure and each dimension high internal consistency. These psychometric indicators indicate acceptable validity and reliability. It is necessary to determine the best cut-off point for a major depressive episode in COVID-19 survivors.

FundingThe Universidad del Magdalena funded Adalberto Campo-Arias and John Carlos Pedrozo-Pupo.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare for the conduct of this research.

To the Universidad del Magdalena for its support in the conduct of the study.