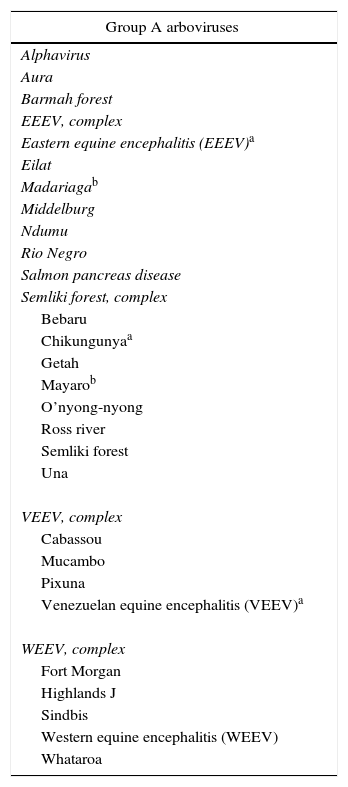

During the last two years, Latin America, in general, and Colombia, in particular, have seen the emergence in a significant part of their territory of new viral tropical infectious agents, not previously described in the region, especially of autochthonous transmission by arthropod vectors.1 The viruses that can be transmitted by this way (in addition to other possible routes, usually secondary) are called arboviruses. This term comes from ar – arthropod bo – borne, virus transmitted by arthropods (mosquitoes or ticks, mainly). In this denomination are found a wide number of viruses that belong to 4 groups, A, B, C and D, of which the most important are found in the groups A and B (Table 1).

Main relevant arboviruses in groups A and B.

| Group A arboviruses |

|---|

| Alphavirus |

| Aura |

| Barmah forest |

| EEEV, complex |

| Eastern equine encephalitis (EEEV)a |

| Eilat |

| Madariagab |

| Middelburg |

| Ndumu |

| Rio Negro |

| Salmon pancreas disease |

| Semliki forest, complex |

| Bebaru |

| Chikungunyaa |

| Getah |

| Mayarob |

| O’nyong-nyong |

| Ross river |

| Semliki forest |

| Una |

| VEEV, complex |

| Cabassou |

| Mucambo |

| Pixuna |

| Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEEV)a |

| WEEV, complex |

| Fort Morgan |

| Highlands J |

| Sindbis |

| Western equine encephalitis (WEEV) |

| Whataroa |

| Group B arboviruses |

|---|

| Flavivirus |

| Aroa |

| Cacipacore |

| Dengue, groupa |

| Gadgets Gully |

| Japanese encephalitis, group |

| Japanese encephalitis |

| Koutango |

| Murray Valley encephalitis |

| St. Louis encephalitis |

| Usutu |

| West Nile virusb |

| Jugra |

| Kadam |

| Kedougou |

| Kokobera, group |

| Modoc, group |

| Tick-borne encephalitis, group |

| Kyasanur forest disease |

| Langat |

| Louping ill |

| Omsk hemorrhagic fever |

| Phnom Penh bat |

| Powassan |

| Royal Farm |

| Tick-borne encephalitis |

| Yaounde |

| Yellow fever, groupa |

| Zikaa |

In group A is found the alphavirus genus (Table 1), which includes the chikungunya virus (CHIKV) and the Mayaro virus, both arthritogenic and circulating in Latin America; the first since 2014 in Colombia. Viruses such as the Ross River, Barmah forest, O’nyong-nyong, Sindbis, and Semliki forest, are also arthritogenic alphaviruses, which are not yet present in Latin America, but that could appear in a future time.1,2

In group B are included relevant viruses such as the dengue virus (DENV) and the Zika virus (ZIKV) (Table 1), which also produce rheumatologic manifestations, although with less commitment in extension and in time, in comparison with the alphaviruses.1,2

The clinical manifestations that these arboviruses can produce are similar. When there is a monoinfection, there are some characteristics of higher predominance in them, however, it has been demonstrated that there might be coinfections3,4 that would make more complex the syndromic diagnosis. For this reason it has been proposed to consider them altogether. For example, the ChikDenMaZika syndrome includes simultaneously CHIKV, DENV, Mayaro virus and ZIKV.5 Their clinical similarities appear to be related with their taxonomy and also with their phylogenetics. Indeed, an evolution is evident, as has been recently demonstrated in dengue (where apparently exists a fifth serotype, DENV-5) and in ZIKV (where an oceanic lineage and a Latin American lineage are recently described).6

The CHIKV infection is characterized, mainly, in its acute phase by fever and migratory bilateral severe polyarthralgias that involve especially joints of hands and feet, generating a significant disability. However, a considerable impact has been demonstrated not only in the acute phase of the disease (the first 3 weeks), but beyond in the sub-acute phase (3–12 weeks) and particularly in the chronic phase (from 12 weeks onwards). In Colombia, where the estimates indicate that more than 3 million cases could have been occurred between 2014 and 2015, a proportion close to 50% could be suffering or being at risk of developing the so-called post-chikungunya chronic inflammatory rheumatism (pCHIK-CIR), observed in multiple cohorts in Sucre,7 Tolima8 and Risaralda,9 confirming previous modeling studies10 and a meta-analysis.11 In summary, 56.6% of patients persisted with pCHIK-CIR beyond 12 weeks post-infection.7–9 Therefore, the pCHIK-CIR is a challenge for the Latin American Rheumatology.12

As it happened with the DENV, the CHIKV and the ZIKV came to stay. Although the epidemic phase of CHIKV ended up, an endemic condition is observed. In Colombia, a total of 18,317 cases of CHIKV have been reported during the first 31 weeks of 2016 (until August 6), 3949 in the Valle del Cauca, 2178 in Santander, 1560 in Tolima and 1415 in Risaralda.13 In the American continent also stands out that 247,626 cases have been notified until the week 32 of 2016 (August 12).14

In new preliminary data from 2 cohorts under follow-up, in Risaralda and Tolima, after one year of infection, is known that in the first of them, 45.6% of the subjects still persist with pCHIK-CIR (previous value <1 year: 53.7%), while in the second, 43.1% (previous value <1 year: 44.3%). These figures indicate the true chronic character of the pCHIK-CIR with the possibility of an inflammatory arthropathy which, in some cases, can be erosive and indistinguishable from a seronegative rheumatoid arthritis.15

As if CHIK were not enough, concern has been raised regarding the possible and nearby circulation of the Mayaro virus, an alphavirus that also can produce acute and chronic joint involvement.16 The country should be prepared, both in the primary and the specialized care, to face this new challenge that could supervene even this same year 2016. Mayaro already circulates in Brazil,17 Venezuela,18 Peru19 and Ecuador.20 A possible circulation in Colombia cannot be ruled out.5

For all these reasons, it becomes imperative to increase the research on these emerging arthritogenic arboviruses, where Rheumatology has a particularly important role not only in clinical,21,22 but also epidemiological and basic research, to better understand their implications not only in the acute phase, but also in the chronic, the risk factors associated with chronicity, the immunological mechanisms involved and the possible alternatives not only for palliative treatment but also for possible prevention and cure.

In conclusion, these arboviruses are having a considerable impact in terms of clinical commitment, disability and even costs,23–25 which entails greater reflection by the multiple specialties involved in their management and research, as is the case of Rheumatology, to generate in addition local research which would have a global repercussion, since Colombia is being the scenario of major contributions for Latin America regarding the pCHIK-CIR,26 and it should be also in the future for other emerging arthritogenic arboviruses.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Morales AJ, Anaya J-M. Impacto de las arbovirosis artritogénicas emergentes en Colombia y América Latina. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2016;23:145–147.