Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic autoimmune disease of variable severity with a tendency to flare up during its course. Without treatment, LN remains one of the main causes of end-stage renal disease and is also associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality. Currently, standard immunosuppression treatment (cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate) has managed to significantly preserve kidney function and improve survival. Unfortunately, a subset of patients with LN do not respond to initial immunosuppression treatment and is defined as refractory, constituting a great challenge given the scarce evidence of alternative therapies based on controlled clinical trials and that sometimes obtain unfavorable results. We also provide an update on the available therapies for refractory LN.

El lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) es una enfermedad autoinmune sistémica de severidad variable, con tendencia a presentar brotes en el trascurso de su evolución. Sin tratamiento la nefritis lúpica (NL) sigue siendo una de las principales causas de enfermedad renal en etapa terminal y también se asocia con un aumento en la morbimortalidad. En la actualidad, el tratamiento de inmunosupresión estándar (ciclofosfamida o micofenolato) ha logrado preservar de forma significativa la función renal y mejorar la supervivencia. Infortunadamente, un subconjunto de pacientes con NL no responde al tratamiento de inmunosupresión inicial y se define como refractario, lo cual constituye un gran desafío debido a la escasa evidencia de terapias alternativas fundamentadas en ensayos clínicos controlados, en ocasiones con resultados desfavorables. En este escrito se presenta una actualización de las terapias disponibles referentes a NL refractaria.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic autoimmune disease of variable severity, with a tendency to present flares during the course of its evolution. Immunological alterations, particularly the production of diverse antinuclear antibodies, are one of its determining characteristics. Both the innate and adaptive immune systems intervene in its pathophysiology, as well as the interaction between genes with environmental factors that cause sustained immunological alterations against autologous nucleic acids.1 The tissue damage attributed to the disease is caused by autoantibodies or deposition of immune complexes, mainly in the kidneys, heart, blood vessels, central nervous system, skin, lungs, muscles and joints, which lead to significant morbidity and an increased mortality.2

SLE has a marked female predominance, with almost 10 women patients for every man affected by the disease. The incidence varies between 0.3 and 31.5 cases per 100,000 individuals per year and has increased over the last 40 years, probably due to the recognition of milder cases. The prevalence worldwide even exceeds 50–100 cases per 100,000 adults.3 An average prevalence of 8.77/10,000 inhabitants has been estimated in Colombia from 2012 to 2016, being more frequent between 45 and 49 years of age. Likewise, a female:male ratio of 8.07:1 has been calculated, while the departments with the highest prevalence in descending order are: Bogotá, Antioquia and Valle del Cauca.4 The severity of the disease varies according to ethnic origin and is more severe in patients of African ancestry and in Latin Americans.

In a cohort of patients with recently diagnosed SLE, LN occurred in 38% of cases, during a mean follow-up of 4.6 years.5 Younger patients, especially men with high anti-DNA titers or moderate to severe activity assessed by validated activity indices, have a higher risk of developing renal involvement.6 According to the Latin American Lupus Study Group (GLADEL, for its acronym in Spanish) cohort, LN is present in 52% of patients with SLE in Latin America, and in Colombia it has been described that up to 55% develop renal involvement.7

It is worth highlighting that LN is the most frequent serious organic manifestation of SLE. Its clinical presentation is manifested by proteinuria (>0.5g per day) or protein/creatinine ratio in urine>0.5mg/mg, or urine protein>3+ by dipstick analysis.8 Unfortunately, about 35% of patients with LN do not respond to initial immunosuppression treatment and are defined as refractory, which constitutes a great challenge due to the scarce evidence of alternative therapies based on controlled clinical trials, sometimes with unfavorable results.9 This review id focused on describing and updating the treatments of refractory LN.

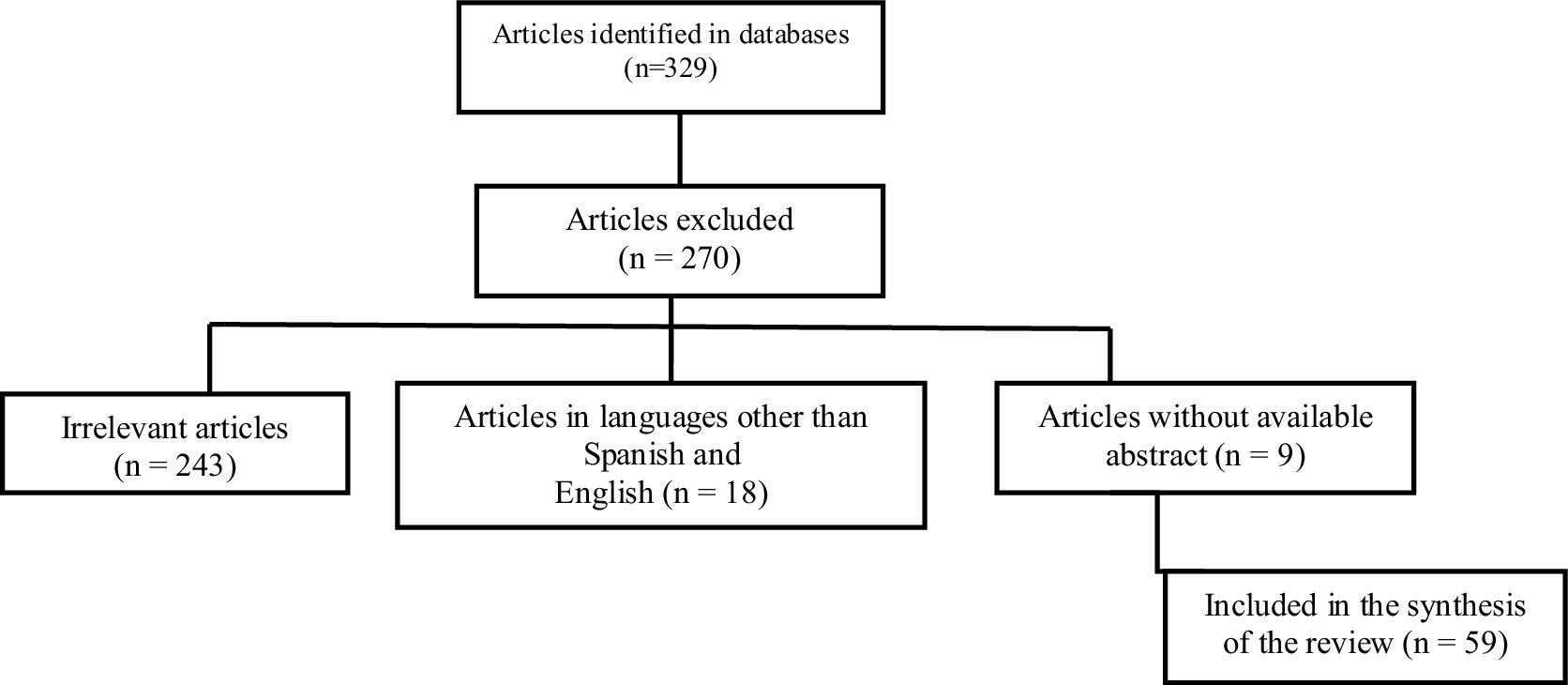

MethodologyA non-systematic narrative review of the literature in English and Spanish was conducted, in accordance with the objective of having the most updated information available for the articles referenced since 2019, in primary databases such as: PubMed, Embase and Lilacs. The medical subject headings terms used were: “refractory lupus nephritis”, “treatment” and “treatment of refractory or recurrent focal or diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis”, which were combined using Boolean operators (AND, OR). A flowchart detailing the search strategy is presented in Fig. 1.

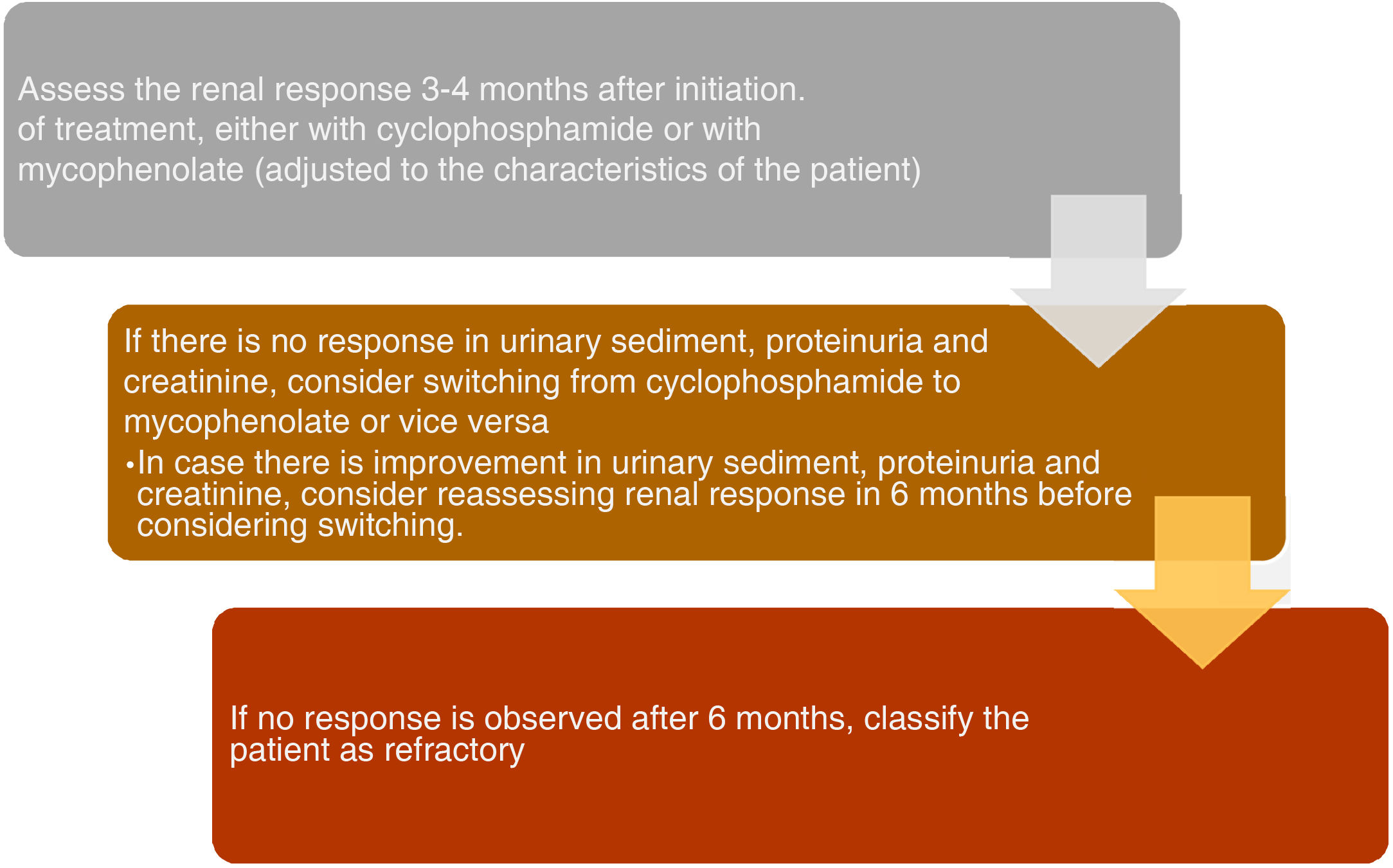

Definitions to assess the response to treatmentPatients who do not achieve a response to the initial immunosuppression treatment are defined as refractory or resistant. It should be noted that true resistance is very infrequent and certain cases are generally misclassified, particularly those that do not achieve complete adherence or present difficulties to continue the prescribed treatment regimen. Currently, there is no consensus on a clear definition of complete response with immunosuppressive treatment in patients with proliferative LN. For this reason, the incidence of refractory LN is variable. EULAR/ERA-EDTA guidelines define refractory disease as a lack of improvement within 3–4 months, failure to achieve a partial response after 6–12 months, or a complete response after 2 years of treatment.10,11

Complete response, which may take up to 3 years to be achieved, is characterized by inactive urinary sediment, decreased proteinuria to <0.5g/day and normal or stable creatinine.12 Because of this, the ACR recommendations suggest to maintain continuity of treatment with the selected induction regimen for another 6 months before considering to change it, unlike what is proposed by the EULAR/ERA-EDTA guidelines, which are in favor of an earlier change (in the first 3 months) since the renal damage is irreversible. Partial response refers to a reduction in proteinuria>50% to a non-nephrotic range (<3.5g/day), an inactive urine sediment and a normal creatinine, which is usually reached after 6–12 months of treatment.13,14

It has been considered to repeat the renal biopsy if the response to immunosuppressive treatment is not clear, specifically when it entails a change in therapeutic intervention. However, defining the response by proteinuria or by biopsy may result in misclassifying some patients as refractory, since many of them may have late or advanced presentations of the disease and may not have the potential to achieve remission due to chronic kidney damage.

The therapeutic approach for patients who are considered resistant to initial therapy, that is, those with clinical or histological evidence of active nephritis, varies with the drug used for induction and the severity of the disease. Those who do not achieve remission after 6 months with cyclophosphamide are switched to mycophenolate, or vice versa.15 Other therapeutic options such as calcineurin inhibitors, plasmapheresis or mesenchymal stem cell transplantation have been proposed, and a case report informs a favorable outcome of CAR-T cells targeting CD19.16 Below, each of these treatments is described according to the levels of evidence currently available.

RituximabRituximab has been considered one of the first treatment alternatives when there is therapeutic failure with mycophenolate and cyclophosphamide. However, the evidence in refractory LN comes from open-label studies, which causes some uncertainty regarding its effectiveness. Despite this, it has shown favorable results in certain cohort studies in which the treatment has been effective in different ethnic groups and for different definitions of refractory LN.17–19 In addition, many differences have been presented regarding the method of evaluation of the response to rituximab, since in some studies the SLAM activity index was used, while in others the British Lupus Isles Assessment Group Index (BILAG) or the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Measure (SLEDAI) were used.20

According to a meta-analysis, the mean follow-up of the patients has been 60 weeks, and rituximab has achieved a surprising overall response rate of 74% in refractory cases. The authors of this study demonstrated a better response rate (either complete or partial) in class III LN, but less frequent in classes IV and V,21 while another meta-analysis estimated a complete response rate of 51% and a partial one of 27%.22 There has been certain variability in the treatment regimens used, but in general the protocol for the treatment of lymphoma (375mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks) or the protocol based on rheumatoid arthritis (1000mg on days 1 and 15) has been applied, with slight modifications in some cases.

The RING study (NCT01673295) is an international randomized clinical trial that recruits patients with the objective of testing the efficacy in achieving a complete renal response in patients with LN with persistent proteinuria (≥1g/day) with at least 6 months of standard therapy. In Colombia, a cohort of 42 patients with severe and refractory SLE treated with rituximab after lack of response to glucocorticoids and at least one other immunosuppressive medication was described.

A reduction in the requirement for glucocorticoids was observed and from the first follow-up at 3 months, 28% achieved complete remission and 36% achieved partial remission, according to the proteinuria. These response criteria were maintained for 12 months.23 Taken together, all this evidence strongly supports the use of rituximab in patients not sufficiently controlled with the initial treatment. Given the determining role that B cells play in the pathogenesis of the disease, and the results that have been shown today, research focused on B cell depletion as one of the main treatment objectives continues.

BelimumabIt has been demonstrated that an increase in BAFF is associated with an early relapse of the disease (usually in less than 1 year). In general, a significant increase in BAFF levels has been described after rituximab treatment, while after 6–8 months, when B-cell repopulation was ongoing, the BAFF levels decreased to basal levels.24 This finding suggests that B cells depletion alone fails to achieve the expected clinical response and that the combination with BAFF inhibition could have a synergistic effect. Moreover, sequential therapy with rituximab and belimumab has been used successfully in several patients with refractory LN and may be a promising therapeutic approach, particularly in patients who present early relapses.25,26

In addition to the reduction of BAFF levels, it has been shown that the combination of rituximab and belimumab significantly reduces the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps.27 To date, the only study published is the BEAT-Lupus, in which the 52 patients who participated received rituximab for lupus nephritis and were divided into the belimumab and placebo groups. There were no restrictions regarding the use of prednisolone or immunosuppressive drugs for the patients who entered the study. The primary endpoint was the decrease in anti-double-stranded DNA antibody levels at 12 weeks (mean of 86 vs.108 IU/mL, P=.004), 24 weeks (69 vs. 99, P<.0001) and 52 weeks (47 vs.193, P=.0003).

A decrease in severe flares was also observed (BILAG A) (3 severe flares versus 10 with placebo, HR 0.27, P=.032). The time until the first moderate or severe flare (BILAG A or 2B) had a trend towards improvement, without statistical significance (8 flares versus 14, P=.14). Safety data were similar in both arms of the study.28 The BLISS BELIEVE study suggests a design to establish the superiority of belimumab in the proposed combinations of the three treatment arms (placebo, rituximab or standard treatment), which allows better long-term observation of a true clinical remission and its durability, as well as to assess more accurately the safety aspects of the drug (final publication is expected).29

In the CALIBRATE study, the addition of belimumab to a treatment regimen with rituximab and cyclophosphamide was safe in patients with refractory LN. This regimen decreased the maturation of transitional B cells to mature naive cells during reconstitution and enhanced negative selection of autoreactive B cells. The clinical efficacy did not improve; however, the study did not have enough statistical power to evaluate the effectiveness of belimumab and was designed primarily to evaluate its safety.30 It is important to highlight that the risk of progression to end-stage renal disease in patients with class IV LN is close to 30%, so the growing evidence of these therapies turns out to be very promising to avoid this outcome.31 It is unknown, if there is a contraindication to the administration of rituximab, whether treatment with other anti-CD20 drugs such as obnituzumab and ofatumumab can obtain the same results, although the latter has been used successfully in a patient with life-threatening refractory LN.32

Calcineurin inhibitorsThe evidence for calcineurin inhibitors has also changed significantly in terms of their efficacy and safety in refractory LN. The most representative inhibitors within this group are cyclosporine and tacrolimus. Both drugs have been studied extensively in LN, especially in Asia, with increasing evidence of their efficacy in refractory LN. Cyclosporine binds to its cytoplasmic receptor, cyclophilin, and the resulting drug-receptor complex binds to calcineurin and interferes with the production of IL-2, leading to a selective and reversible inhibition of the T-lymphocyte-mediated immune response. In addition to its strong immunosuppressive action, it has been demonstrated that cyclosporine has direct antiproteinuric effects. This last mechanism is related to the stabilization of actin in podocytes.33

Tacrolimus binds to a different cytoplasmic receptor, FK binding protein-12, which then interacts with calcineurin.34 It is worth highlighting that this group of medications is able to reduce proteinuria using non-immune mechanisms, which imply a great bias regarding the wrong interpretation of a favorable clinical response. In addition, proteinuria levels have been taken as one of the main endpoints in several of their studies, so the interpretation of a renal response must be evaluated together with other variables such as creatinine levels and urinary sediment. In a prospective, open-label randomized study for the induction treatment of LN, “multitarget” therapy, which includes glucocorticoids, tacrolimus and MMF, was investigated and was demonstrated to be superior to intravenous cyclophosphamide in the induction of remission at 6 months. The observed difference was mainly attributed to a better response of class IV and V or combined IV/V LN.35

It should be highlighted that many patients had received cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate before randomization and the vast majority received intermediate doses of glucocorticoids. The complete renal remission rate in the intention-to-treat analysis was significantly higher (50% vs. 5%) in the “multitarget” therapy group, while the partial response did not differ between both treatment groups.36 In a prospective observational study conducted in China, tacrolimus (2 or 3mg, according to the body weight) was added to the treatment in 26 patients resistant to cyclophosphamide. Complete response was observed in 38.5% and partial response in 50%, accompanied by a decrease in proteinuria from 6.9g/day to 1.11g/day, together with a significant decrease in SLEDAI. Remarkably, the patients classified as non-responders had class III LN in the renal biopsy.37

The response of the refractory cases (classes IV and V or combined IV/V) was also observed in a Korean study, with a response rate of 78%. The proteinuria decreased from a baseline creatinine/protein ratio of 2.19 to 0.44g/g of creatinine, after 12 months. Despite these favorable results, the mean dose of prednisolone remained higher than 10mg/day in the last follow-up.38 According to the observations of the efficacy of tacrolimus, treatment with cyclosporine A has also achieved good response rates in refractory LN. A series of 6 refractory cases with LN who received cyclosporine A because they did not achieve remission after mycophenolate (2−3g per day) has been described. The addition of cyclosporine A (2.6–3.7mg/kg/day) led to a reduction in proteinuria from 2.4g/day to 0.5g/day. Four patients achieved complete remission, one had partial remission and the other did not reach any response.39

Although numerous studies have demonstrated that calcineurin inhibitors have a good safety profile, some warnings come into consideration. The first of them is that their intrinsic hemodynamic effect (decrease in the glomerular filtration rate due to intrarenal vasoconstriction) could lead to acute kidney injury or even to irreversible chronic nephrotoxicity.40 The second is the difficulty of adjusting the dose, since their blood concentration must be monitored by levels. The third is that hypertension and hyperglycemia are important complications inherent to their continuity.41 Finally, the secondary hemolytic uremic syndrome, due to direct endothelial damage, can become a life-threatening adverse event.42 A new calcineurin inhibitor, voclosporin, has recently demonstrated its efficacy over placebo in a phase II clinical study and has been tested in a phase III study (AURORA 1), being another promising option for the treatment of refractory LN.43

Extracorporeal therapy, plasmapheresis and immunoadsorptionThe evidence for extracorporeal therapy such as plasmapheresis and immunoadsorption in refractory LN is minimal, since it is mainly based on case reports and observational studies. A randomized controlled trial, conducted by the Lupus Nephritis Collaborative Study Group, examined the effectiveness of plasmapheresis when added to standard therapy in patients with severe LN without achieving improvement in clinical outcomes.44 The most consistent scientific evidence suggests that the addition of extracorporeal therapy could be effective in the treatment of pregnant women with signs of active disease, antiphospholipid syndrome or refractory LN.45,46

Immunoadsorption has replaced plasmapheresis in many countries because patients experience fewer systemic effects and secondary adverse events, especially hemorrhages, anaphylactic complications, and life-threatening infections.47–49 In addition, it has advantages in the elimination of specific antibodies, as has been demonstrated in a large observational study.50 Among the more representative studies, one which included 8 patients with refractory disease, who underwent immunoadsorption, received cyclophosphamide and achieved an improvement in the levels of proteinuria and creatinuria was described.51 Extracorporeal therapy could be a reasonable option in patients with a refractory disease course or in those who have an absolute contraindication to the intensification of conventional treatment, particularly those who present with a severe infection at the same time as the renal flare.

Mesenchymal stem cell transplantationIn some studies, allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation has been used with good results. MSCs have immunomodulatory functions, including their ability to stimulate the differentiation and proliferation of regulatory T cells.52 In one study, MSC transplantation was performed in 15 patients with refractory LN. After 12 months of follow-up, the proteinuria decreased from 2505mg/day to 858mg/day. Along with this result, a significant improvement in SLEDAI was also observed, with a decrease from 12.2 to 3.2 in the same observation period. There were no life-threatening side effects after the procedure, unlike what happens in autologous stem cell transplant.53

In a follow-up study of the same group, a remission rate of 60.5% and a relapse rate of 22.4% were established.54 Another subsequent multicenter study that included the majority of patients with LN reported remission and a partial clinical response in 27.5% and 32.5%, respectively. The overall survival rate during the 12-month follow-up period was 92.5%, with no procedure-related deaths.55 Despite being a quite promising therapy, more experience, technological development and highly qualified personnel are required in Colombia to apply it systematically.

Alternative immunosuppressive therapyThere are few data on alternative treatments; it has been described that mizoribine, an immunosuppressant that inhibits the inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, was used in a Japanese series of 17 patients with resistant LN. After 24 months, a decrease in the urinary excretion of proteins from 194 to 114mg/dl was observed.56 A series of 7 patients with LN who presented failure to cyclophosphamide is described, for which additional treatment with high doses of immunoglobulin (1–6 cycles of 400mg/kg for 5 days) was indicated, and a significant reduction in proteinuria was achieved at the 6-month follow-up, accompanied with an increase in albumin and a decrease in serum cholesterol.57

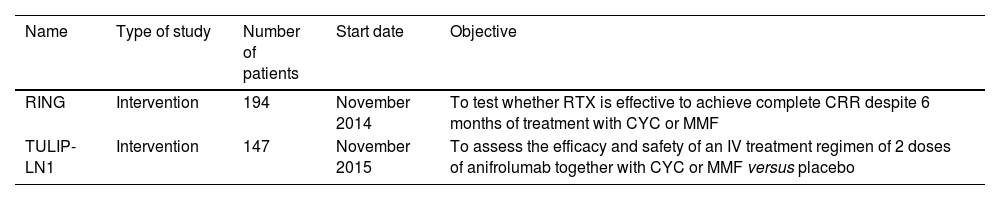

Emerging therapies have not achieved good results and in many studies patients with NL have been excluded (such as in the cases of abatecept and epratruzumab). The TULIP-LN1 study, which examines the efficacy of anifrolumab in active proliferative LN, is ongoing (NCT02547922) awaiting to obtain favorable results. The most representative ongoing clinical studies are presented in Table 1.

Ongoing clinical studies.

| Name | Type of study | Number of patients | Start date | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RING | Intervention | 194 | November 2014 | To test whether RTX is effective to achieve complete CRR despite 6 months of treatment with CYC or MMF |

| TULIP-LN1 | Intervention | 147 | November 2015 | To assess the efficacy and safety of an IV treatment regimen of 2 doses of anifrolumab together with CYC or MMF versus placebo |

CYC: cyclophosphamide; MMF: mycophenolate; CRR: complete renal response; RTX: rituximab.

General supportive measures in all patients with focal or diffuse LN include dietary sodium and protein restriction, control of blood pressure, minimization of proteinuria with inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, use of antimalarials (unless there is any contraindication) and treatment of dyslipidemia.58 In addition, some patients may present concomitant thrombotic microangiopathy. The potential causes of thrombotic microangiopathy in patients with SLE include the thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, the complement-mediated, and the nephropathy due to antiphospholipid antibodies syndrome.42 The exclusion of these differential diagnoses or progression to membranous LN should be considered before evaluating treatment refractoriness, since both entities may require completely different treatment approaches.

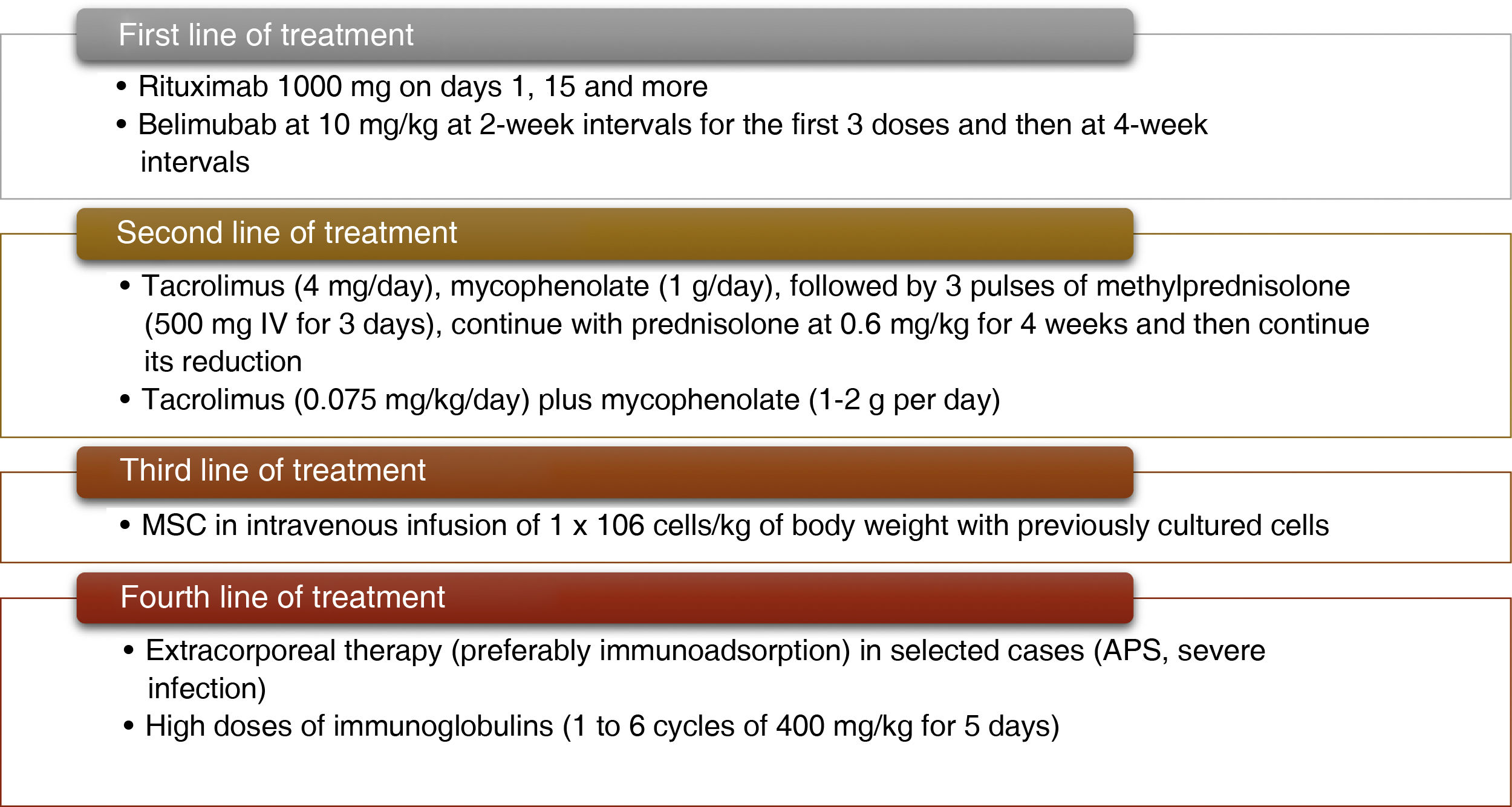

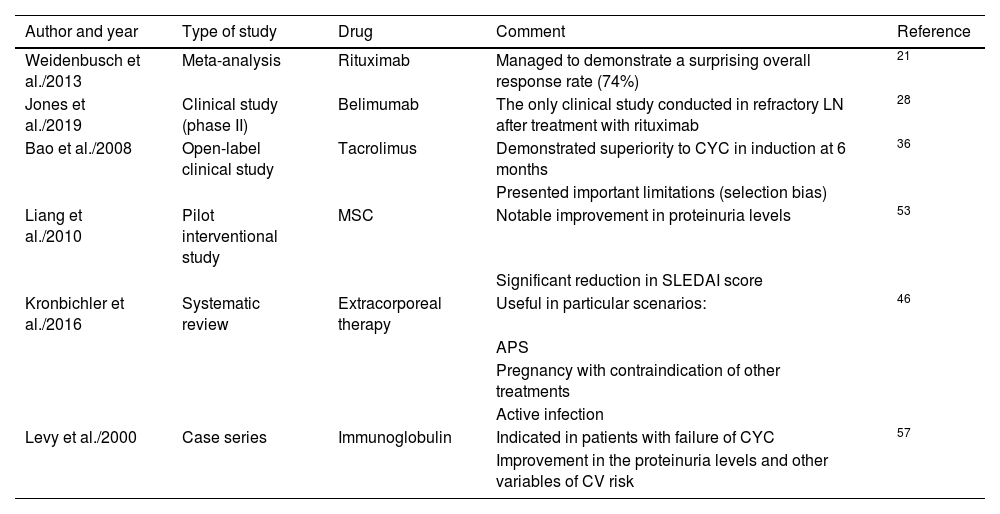

Finally, Fig. 2 describes how a patient is classified as refractory, while Fig. 3 shows the hierarchical order of the treatment for refractory LN. Furthermore, the most relevant articles that support the recommendations of the treatment lines mentioned in Fig. 3 are shown in Table 2.

Most representative articles to establish the lines of treatment in hierarchical order.

| Author and year | Type of study | Drug | Comment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weidenbusch et al./2013 | Meta-analysis | Rituximab | Managed to demonstrate a surprising overall response rate (74%) | 21 |

| Jones et al./2019 | Clinical study (phase II) | Belimumab | The only clinical study conducted in refractory LN after treatment with rituximab | 28 |

| Bao et al./2008 | Open-label clinical study | Tacrolimus | Demonstrated superiority to CYC in induction at 6 months | 36 |

| Presented important limitations (selection bias) | ||||

| Liang et al./2010 | Pilot interventional study | MSC | Notable improvement in proteinuria levels | 53 |

| Significant reduction in SLEDAI score | ||||

| Kronbichler et al./2016 | Systematic review | Extracorporeal therapy | Useful in particular scenarios: | 46 |

| APS | ||||

| Pregnancy with contraindication of other treatments | ||||

| Active infection | ||||

| Levy et al./2000 | Case series | Immunoglobulin | Indicated in patients with failure of CYC | 57 |

| Improvement in the proteinuria levels and other variables of CV risk |

MSC: mesenchymal stem cells; CV: cardiovascular; CYC: cyclophosphamide; APS: antiphospholipid syndrome; SLEDAI: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index.

Currently, novel treatments are known with good clinical results, as shown in the case of sequential therapy with rituximab and belimumab, given that they present better efficacy and safety profiles. According to the available evidence, these medications are considered the first line of treatment in refractory LN. They are preferred particularly in cases of class III LN, although they may be useful in more severe cases or in those with late presentation. Unlike rituximab and belimumab, calcineurin inhibitors have shown better response rates in advanced stages of the disease (LN classes IV and V or combined IV/V) with greater reductions in proteinuria levels.

It should be taken into account that proteinuria may not accurately reflect renal activity in these cases, either due to chronic and irreversible damage to the glomerulus, or due to the direct antiproteinuric effect of this group of drugs. A major limitation is that the majority of the evidence comes from Asian patients, which greatly prevents the extrapolation of the results. Added to this, it has previously been demonstrated that the responses to different treatments vary by ethnic origin, and the results may not be reproducible in patients of African or Latin American descent. Other important difficulties are that patients require careful monitoring of kidney function, drug levels, and surveillance of other comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension, which can be aggravated by the side effects. Extracorporeal therapy could be an option in patients with a refractory course or in those who have an absolute contraindication to intensification of conventional treatment, such as in the case of an active infection.

MSC transplantation appears to be a promising and safe treatment, with very few side effects. Unlike autologous stem cell transplantation, studies with higher levels of evidence are required to implement it systematically. For their part, the available studies of alternative immunosuppressive therapies have been very discouraging. According to current data, it is possible that immunoglobulin has some benefit, however, in the series described, prolonged cycles have been required, with an exponential increase in costs. It is expected that anifrolumab may have good results in LN to consider it later in studies of refractory LN.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.