Modifying the immune response induced by biological therapies and the recently approved JAK inhibitors has significantly altered the treatment and monitoring of chronic autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.1,2 While these agents are generally well-tolerated, post-marketing surveillance data reveal a frequent association with adverse events, including allergic, immunological, infectious, and other unwanted reactions.3 Therefore, effective risk management in therapy involves closely monitoring patients to identify, prevent, and minimize events that could potentially compromise their safety during the use of these drugs.4

In 2016, the Asociacion Colombiana de Reumatologia (ASOREUMA) published a set of recommendations for the safe use of biological therapies in clinical practice.5 In Colombia, the estimated prevalence of patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving biological therapies is 14.7%, while 1.3% are prescribed JAK inhibitors.6

The purpose of this document is to provide updated information to help rheumatologists, related specialists, and other healthcare professionals effectively manage the risks associated with the use of biological therapies and targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs in patients with chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. A panel of experts from ASOREUMA, after reviewing the available evidence, presents recommendations for managing risks when prescribing these therapies in various clinical scenarios, such as cancer, surgery, tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis, vaccination, cardiovascular disease, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. Implementing these recommendations in daily clinical practice aims to minimize potential adverse effects associated with these treatments and ensure proper follow-up care for patients.

MethodsParticipants and consensus formulationA multidisciplinary development group, consisting of eight clinical experts from rheumatology, infectious diseases, and pulmonology, was formed. All members had extensive experience in prescribing and monitoring therapy with biologic or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs in patients with various diseases. An independent methodological team (Epithink Health Consulting) supported the development of the consensus. All members of the development group disclosed their interests, and none had conflicts of interest regarding their participation in the consensus (see Appendix A, Supplementary material 1).

During a group session, the team defined the questions to be updated and the new questions to be addressed as part of this consensus. The selection criteria were based on the following factors: 1) relevance to current clinical practice, 2) new relevant evidence on effectiveness and safety, 3) new relevant evidence on changes in the clinical context, 4) the need to update a specific question, and 5) the priority for updating that question.

Searching and selecting evidenceSystematic searches for relevant evidence were conducted for each research question. The evidence that informs this consensus is presented in the Supplementary Material. Different search strategies were employed for each topic, aiming to achieve the best balance between sensitivity and specificity. These strategies were written in English. Literature searches were performed in the MEDLINE-PubMed database (including the In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations section); EMBASE (from 1947 to the search date); EBM Reviews-Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (since 2005); the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects; and LILACS.

Two methodological experts screened the search results by title and abstract, applying predefined selection criteria based on the guiding thematic questions (Appendix A, Supplementary material 2). Posters, abstracts, and letters to the editor were excluded from the review. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus. The selected references were then reviewed in full text, and their inclusion was determined in collaboration with the clinical experts. The results of this process are summarized in a PRISMA7 flowchart for each reviewed topic (Appendix A, Supplementary material 2).

Delphi methodThe evidence for each question was reviewed, and relevant information was extracted to develop a questionnaire. In the next phase, eight additional clinical experts from different disciplines joined the panel. The first round of consensus was conducted in a blinded, virtual, and asynchronous manner. Based on the evidence and clinical experience, the experts assessed their level of agreement with risk management statements related to the prescription of biological therapies or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs in Colombia, using a Likert scale. The group's level of agreement was determined through analysis of the first round (Appendix A, Supplementary material 3). Following this, a synchronous session was held to discuss the contents and conduct a second round of assessments, leading to the formulation of the final recommendations.

Other topics that were not subject to updates can be found in the consensus document Risk Management for the Prescription of Biological Therapies.5

Ethical considerationsThis study did not require approval from an ethics committee or informed consent, as it did not involve research subjects.

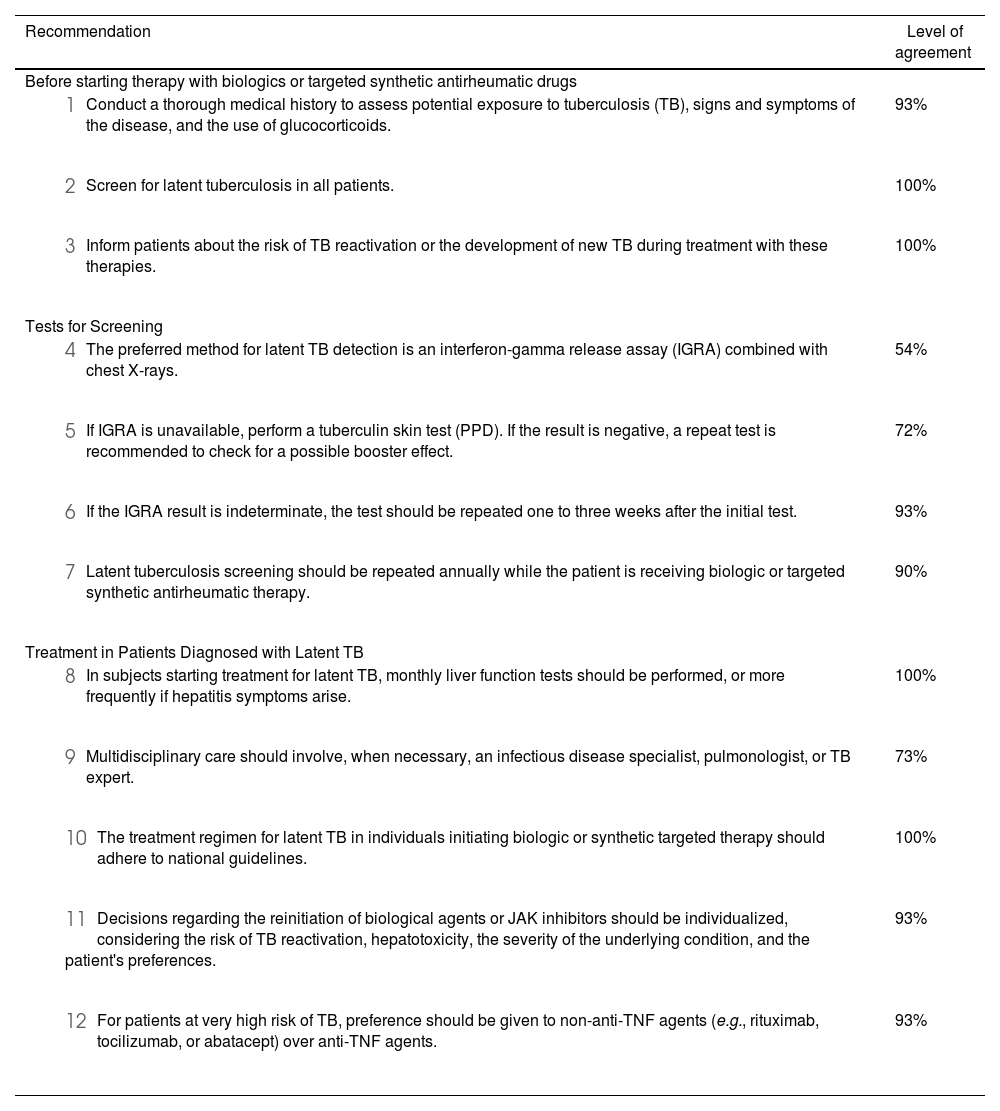

ResultsRecommendations for risk management in the use of biological therapies or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugsLatent tuberculosis (LTB)Current guidelines recommend screening for latent tuberculosis (LTB) in all individuals being considered for treatment with targeted biologic or synthetic agents, regardless of their TB risk factors.8 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends using both the purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) to diagnose LTB and reduce the risk of false negatives.9 Evidence, largely from observational studies, suggests that adding IGRA to standard practice10,11 may improve the identification of LTB cases.12–14 However, in Colombia, where IGRA availability is limited, screening and follow-up continue to rely on PPD testing and chest X-rays.15 This is especially important since a negative IGRA or PPD result does not fully exclude active TB or rule out LTB. In all cases, clinical professionals are encouraged to assess each patient's TB risk and the type of therapy being considered about the likelihood of TB reactivation, considering the high frequency of positive tuberculin tests in Colombian patients with rheumatoid arthritis, even before starting biological therapy.16

Screening should be periodically reassessed during therapy with biologics or synthetic targeted antirheumatic drugs, especially if risk factors emerge or change over time. While there is no consensus on the exact frequency of reassessments, annual monitoring is generally recommended,17–22 particularly in countries with a high prevalence of TB,8 even for those receiving isoniazid prophylaxis.23–25

Various regimens are available for treating LTB, including isoniazid9,26–28 alone or in combination with rifampicin28 or rifapentine.8 This consensus panel supports adherence to national guidelines, which recommend six months of self-administered isoniazid treatment with monthly follow-ups, or a short-term, weekly regimen with isoniazid and rifapentine for three months under supervised treatment.15 Although chemoprophylaxis studies suggest that TB reactivation cannot always be fully prevented during long-term anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy, periodic assessments are necessary to detect reactivation cases during biological therapy.29

There is evidence of an increased risk of TB reactivation with products such as monoclonal antibodies against TNF,30–35 followed by JAK inhibitors and agents targeting interleukin (IL-1).36 Studies of biological agents other than anti-TNF therapies have limitations in quality and performance, particularly in low TB-prevalence settings, leading to an assumption of a theoretical, but lower, risk of TB reactivation.37–40 The risk of reactivation or de novo TB appears to be relatively low with treatments such as apremilast, ustekinumab, secukinumab, and rituximab. Nonetheless, LTB screening should always precede the initiation of biological therapy or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs,41 particularly as the use of immunosuppressive drugs like glucocorticoids may increase the risk of TB.

The evidence concerning the optimal timing for starting or restarting biological therapies in patients undergoing LTB treatment is not well-defined and remains variable.23,42 Most studies suggest that biologics can be initiated or resumed three to six weeks after starting LTB chemoprophylaxis.28,43 However, this timing should be individualized based on factors such as the patient's risk of developing active TB, the potential for hepatotoxicity with LTB treatment, the severity of the underlying disease, and patient preference.44Table 1 summarizes the recommendations for monitoring and treating LTB.

Summary of recommendations on latent tuberculosis and the use of biological therapies or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs.

| Recommendation | Level of agreement |

|---|---|

| Before starting therapy with biologics or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs | |

| 93% |

| 100% |

| 100% |

| Tests for Screening | |

| 54% |

| 72% |

| 93% |

| 90% |

| Treatment in Patients Diagnosed with Latent TB | |

| 100% |

| 73% |

| 100% |

| 93% |

| 93% |

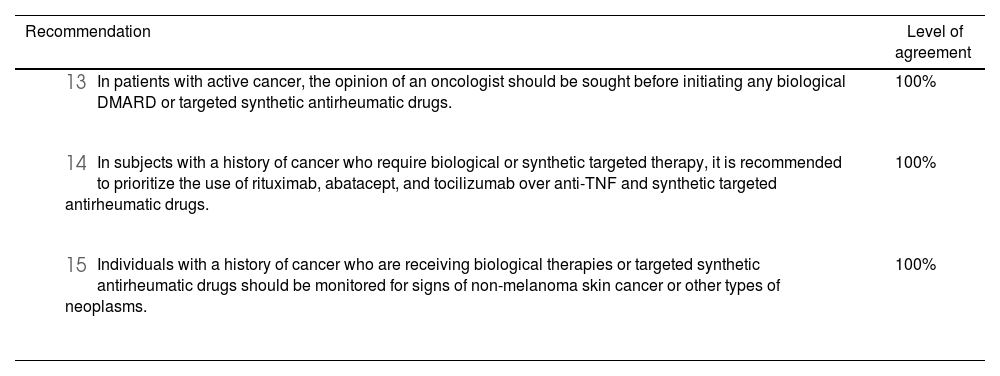

Evidence from meta-analyses of clinical trials45–48 generally supports the safety of biologic therapies (anti-TNF,49–52 JAK inhibitors, IL-17A inhibitors,53 IL-23A inhibitors,53 IL-6 inhibitors,49,51,54 rituximab,49,50,55 IL-1 inhibitors,50 and abatacept56) in patients with a history of malignancy. However, some cohort registries suggest, though inconclusively, an increased risk of malignancy with long-term use of anti-TNF therapy.49,55 These studies recommend against the use of biologic drugs in patients with active cancer,49 while some guidelines advise against using anti-TNF therapies in patients with pre-existing cancer, preferring instead conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), rituximab, abatacept, or tocilizumab.49

When considering the use of biologic or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs in subjects with a history of cancer, several factors must be taken into account. These include an individualized assessment of patient values and preferences, the stage of the disease, prognosis, potential for cure, life expectancy, and quality of life.49 It is also crucial to assess potential interactions between chemotherapy, glucocorticoids, the type of cancer, and the use of biologic or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs, as well as the overall risk-benefit profile of starting these therapies. Similarly, the panel considered that, in cases of active cancer and high disease activity, the involvement of an oncologist in the therapeutic decision-making process is essential. Table 2 outlines the recommendations for risk management in patients with cancer.

Summary of recommendations in the context of cancer and the use of biological therapies or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs.

| Recommendation | Level of agreement |

|---|---|

| 100% |

| 100% |

| 100% |

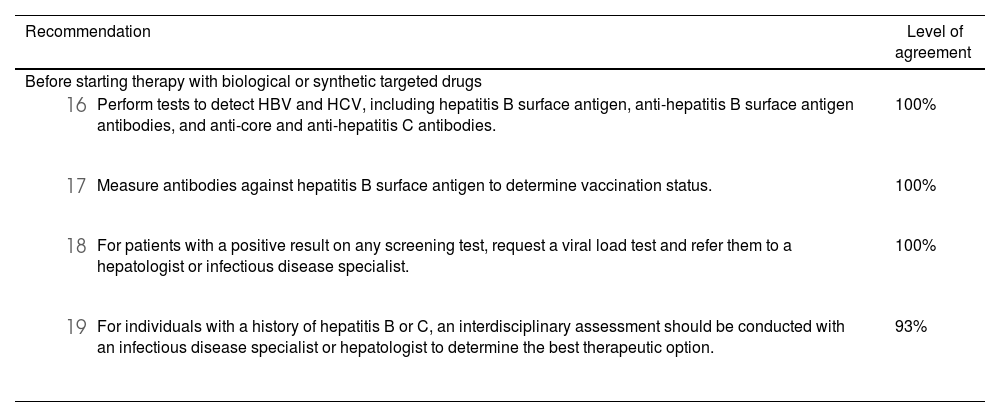

Based on the evidence, due to the potential risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation associated with therapy, all patients should be tested for viral hepatitis before initiating biologic or synthetic targeted agents.57 Testing for HBV surface antigen (HBsAg), anti-HBV surface antigen antibody (HBsAb), or anti-HBV core antibody (HBcAb) is recommended.58 In patients with positive test results, HBV-DNA levels should be assessed to differentiate between active carriers, who should be treated before starting biologic or synthetic targeted antirheumatic drugs. For inactive HBV carriers, prophylactic treatment should be initiated before starting immunosuppressive therapy59 and continued for at least six to twelve months after completing treatment with immunosuppressive drugs.57,60

While studies indicate a very low risk of hepatitis C virus (HCV) reactivation, particularly with anti-TNF agents, testing for anti-HCV antibodies and, if positive, HCV-RNA levels should be conducted in all patients receiving biologic or synthetic targeted therapies.17,61 Patients with detectable HCV-RNA should be monitored during treatment and referred to a hepatologist or infectious disease specialist for antiviral therapy as needed.62,63Table 3 provides a summary of recommendations related to viral hepatitis.

Summary of recommendations regarding viral hepatitis and the use of biological therapies or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs.

| Recommendation | Level of agreement |

|---|---|

| Before starting therapy with biological or synthetic targeted drugs | |

| 100% |

| 100% |

| 100% |

| 93% |

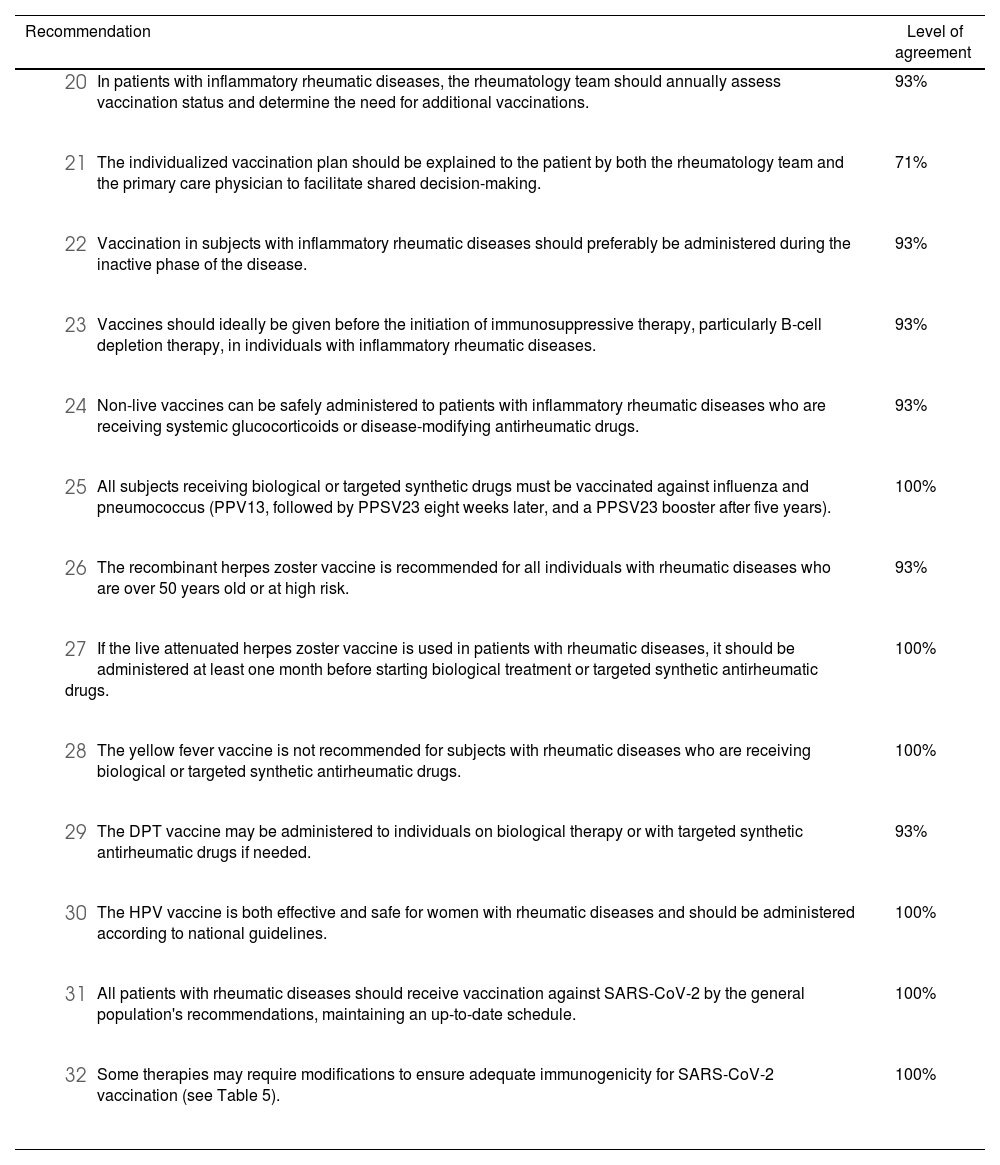

Table 4 summarizes the recommendations for vaccine use in patients receiving biologics and JAK inhibitors. Studies on the influenza vaccine in patients treated with anti-TNF agents have shown that lower antibody titers do not correlate with reduced seroprotection.64 Appropriate immune responses have also been observed in individuals treated with rituximab, abatacept, tocilizumab,64,65 secukinumab,66,67 and JAK inhibitors.68–70

Summary of vaccination recommendations for patients on biological therapies or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs.

| Recommendation | Level of agreement |

|---|---|

| 93% |

| 71% |

| 93% |

| 93% |

| 93% |

| 100% |

| 93% |

| 100% |

| 100% |

| 93% |

| 100% |

| 100% |

| 100% |

Similarly, the efficacy and safety of pneumococcal vaccination have been assessed in various populations with autoimmune diseases.64,68,71–74 These studies indicate no significant impairment in vaccine response or serious adverse events in patients treated with different biological or synthetic targeted antirheumatic drugs, including rituximab, tocilizumab, abatacept, tofacitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib. However, long-term studies on the persistence of humoral responses and immunological memory are still lacking.75

In contrast, evidence regarding the immunogenicity and safety of herpes zoster (HZ) vaccines in patients with rheumatic diseases suggests that the recombinant vaccine performs better than the live attenuated vaccine, although both vaccines have acceptable efficacy, and a similar rate of serious adverse events compared to the general population.76–79 The live attenuated HZ vaccine is more cost-effective in individuals aged 60 to 69 years.80

Women with rheumatic diseases who are undergoing immunosuppressive treatment are at higher risk than the general population for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and subsequent cervical cancer.81,82 The quadrivalent HPV vaccine is well tolerated, reasonably effective, and does not appear to increase disease activity.83–85 Additionally, evidence suggests that anti-TNF therapies do not affect seroconversion following vaccination.86,87

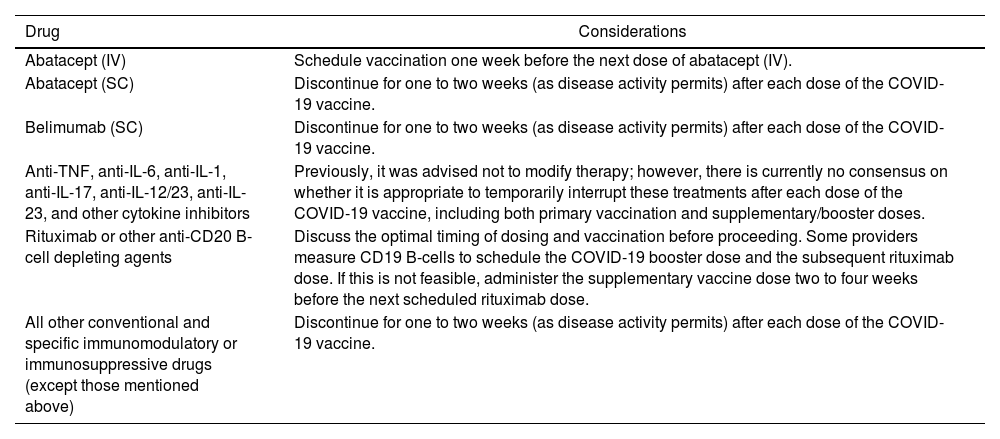

Currently, available data on the correlation between antibody titers and immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are limited. It is known, however, that the immune response in subjects with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases receiving systemic immunomodulatory therapies is typically reduced in both magnitude and duration compared to the general population.88–92 Aside from known allergies to vaccine components, there are no additional contraindications for COVID-19 vaccination in this patient group, where the benefits of vaccination generally outweigh the risks of new-onset autoimmunity.89 To enhance immunogenicity, modification of DMARD treatment around the time of vaccination is recommended89,93,94 (Table 5). Finally, individual cases should be assessed in consultation with infectious disease specialists, especially when considering the timing of vaccination about starting biologic therapy or JAK inhibitors. In cases where patients have a history of herpes infection or are on high-dose glucocorticoids or other immunosuppressants, the timing of vaccination may need to be adjusted. In all instances, healthcare professionals should carefully review the medication insert for each drug regarding vaccination safety and potential interactions.

Considerations for the timing of immunomodulatory therapy and COVID-19 vaccination.

| Drug | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Abatacept (IV) | Schedule vaccination one week before the next dose of abatacept (IV). |

| Abatacept (SC) | Discontinue for one to two weeks (as disease activity permits) after each dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. |

| Belimumab (SC) | Discontinue for one to two weeks (as disease activity permits) after each dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. |

| Anti-TNF, anti-IL-6, anti-IL-1, anti-IL-17, anti-IL-12/23, anti-IL-23, and other cytokine inhibitors | Previously, it was advised not to modify therapy; however, there is currently no consensus on whether it is appropriate to temporarily interrupt these treatments after each dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, including both primary vaccination and supplementary/booster doses. |

| Rituximab or other anti-CD20 B-cell depleting agents | Discuss the optimal timing of dosing and vaccination before proceeding. Some providers measure CD19 B-cells to schedule the COVID-19 booster dose and the subsequent rituximab dose. If this is not feasible, administer the supplementary vaccine dose two to four weeks before the next scheduled rituximab dose. |

| All other conventional and specific immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive drugs (except those mentioned above) | Discontinue for one to two weeks (as disease activity permits) after each dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. |

Moderate level of recommendation based on consensus from the American College of Rheumatology Guidance for COVID-19 Vaccination in Patients with Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases: Version 4.

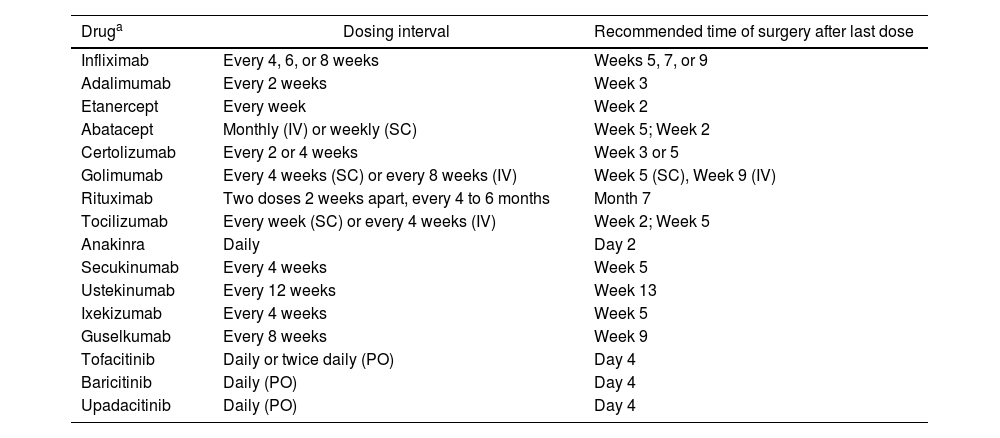

Evidence from meta-analyses95–99 has reported an increased perioperative risk of infection, and the risk-benefit balance of continuing or discontinuing biologic or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs should be carefully considered. The American College of Rheumatology and the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons guidelines 100 recommend discontinuing biologic drugs 1 to 13 weeks before surgery, depending on the half-life of the specific drug (Table 6). Recent meta-analyses have shown a significant increase in postoperative infectious complications in patients on anti-TNF therapy,97 recommending that anti-TNF agents be withheld for two half-lives before surgery99 and restarted two to three weeks post-surgery, provided wound healing is satisfactory.101

Management of biologics and other drugs in the perioperative setting for patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

| Druga | Dosing interval | Recommended time of surgery after last dose |

|---|---|---|

| Infliximab | Every 4, 6, or 8 weeks | Weeks 5, 7, or 9 |

| Adalimumab | Every 2 weeks | Week 3 |

| Etanercept | Every week | Week 2 |

| Abatacept | Monthly (IV) or weekly (SC) | Week 5; Week 2 |

| Certolizumab | Every 2 or 4 weeks | Week 3 or 5 |

| Golimumab | Every 4 weeks (SC) or every 8 weeks (IV) | Week 5 (SC), Week 9 (IV) |

| Rituximab | Two doses 2 weeks apart, every 4 to 6 months | Month 7 |

| Tocilizumab | Every week (SC) or every 4 weeks (IV) | Week 2; Week 5 |

| Anakinra | Daily | Day 2 |

| Secukinumab | Every 4 weeks | Week 5 |

| Ustekinumab | Every 12 weeks | Week 13 |

| Ixekizumab | Every 4 weeks | Week 5 |

| Guselkumab | Every 8 weeks | Week 9 |

| Tofacitinib | Daily or twice daily (PO) | Day 4 |

| Baricitinib | Daily (PO) | Day 4 |

| Upadacitinib | Daily (PO) | Day 4 |

SC: Subcutaneous; IV: Intravenous; PO: Oral route.

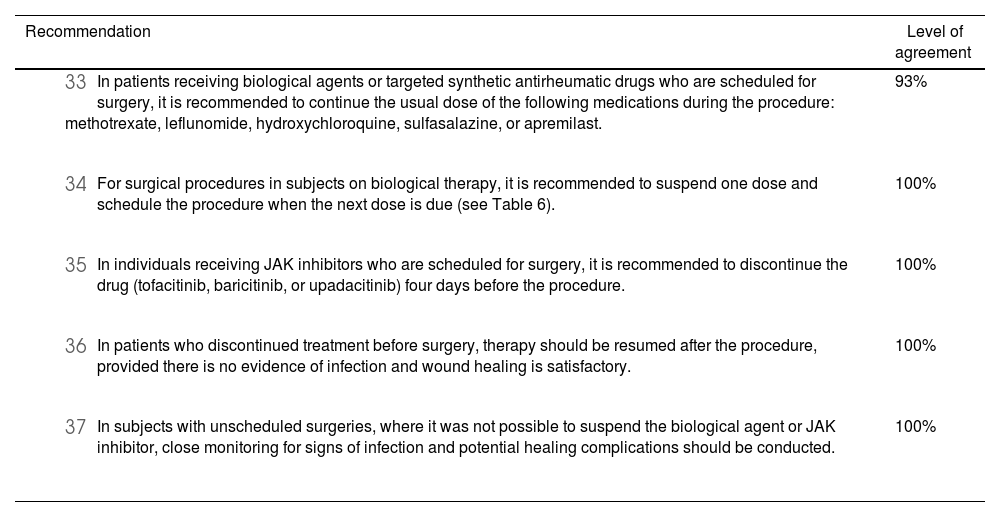

Close monitoring of wound healing and signs of systemic inflammatory response is critical, particularly in emergency surgeries where discontinuation of biologic therapy was not possible. This is especially important in patients with other risk factors for infection, such as increased disease activity, glucocorticoid use, smoking, diabetes,99 or a high risk of wound dehiscence.102 Biologic therapy should be resumed as soon as possible after complete wound healing.103,104Table 7 outlines recommendations for surgical procedures in individuals using biologics or JAK inhibitors.105

Summary of recommendations for surgical interventions in patients receiving biological therapies or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs.

| Recommendation | Level of agreement |

|---|---|

| 93% |

| 100% |

| 100% |

| 100% |

| 100% |

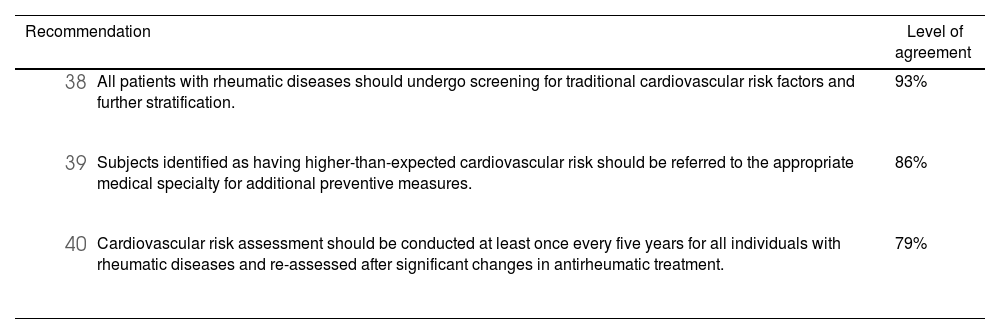

Several DMARDs, including anti-TNF agents, abatacept, and IL-6 inhibitors, appear to improve various markers of cardiovascular disease105 (such as significant reductions in leptin and resistin, along with an increase in adiponectin and reduction in the atherogenic and insulin resistance indices) and reduce cardiovascular events in cohort studies of patients with rheumatic diseases.106–108 In subjects with atherosclerosis treated with tofacitinib106 and those with rheumatoid arthritis managed with anti-TNF agents or JAK inhibitors,109 cohort studies have shown a slight decrease in carotid intima-media thickness. However, it remains unclear whether this improvement is due to a reduction in overall disease activity or to specific atheroprotective effects. Clinical trials with tocilizumab110 and baricitinib111 have shown a significant increase in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, with no significant differences in major cardiovascular outcomes. Targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs may carry a slightly higher risk of thrombotic events than standard therapy in some patients, but the evidence is limited, and long-term clinical studies are needed.112

Current recommendations for cardiovascular risk screening are based on international guidelines and expert consensus.113 The panel emphasizes the importance of risk stratification, using the Framingham scale adapted for Colombia, by any physician on the multidisciplinary care team. Individualized decisions should be made to assess and mitigate cardiovascular risk in patients on targeted biological or synthetic therapies (see Table 8).

Summary of recommendations regarding cardiovascular disease in patients receiving biological or targeted synthetic antirheumatic therapies.

| Recommendation | Level of agreement |

|---|---|

| 93% |

| 86% |

| 79% |

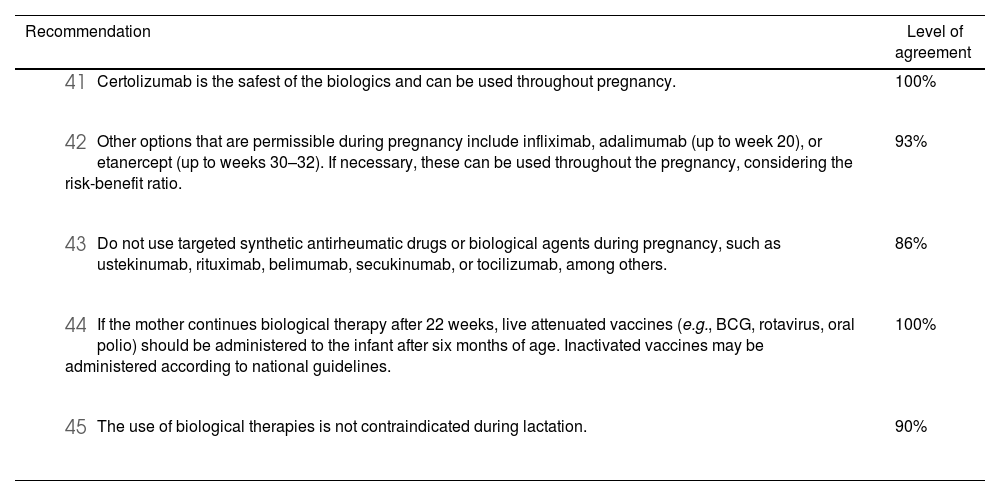

Overall, studies on the long-term effects of targeted biological or synthetic drugs during pregnancy or lactation on child health and development are limited and often of low quality. Therefore, factors specific to the disease—such as treatment indications, drug dosage, disease activity, degree of systemic inflammation, organ involvement, comorbidities, other medications, and the risk of disease flare during pregnancy—must be carefully considered. Drug-related factors, including molecular structure, the likelihood of crossing the placental barrier, exposure duration, and the timing of administration, along with clinically significant and long-term effects on the newborn exposed in utero, should also be considered.114 Additionally, factors such as personal experience with a particular drug, its availability in the country, and its teratogenic classification are important considerations.

Studies indicate that women who wish to become pregnant and are on biological therapy do not have higher rates of spontaneous abortion or congenital malformations compared to pregnant women who used biologics before pregnancy.115 The best quality studies assessing safety during pregnancy have been conducted for certain drugs. The highest placental transfer has been reported for infliximab and adalimumab, low for etanercept, and extremely low for certolizumab.116,117 Recommendations regarding the timing of drug use during pregnancy are based on evidence of potential associations with adverse fetal events.118–121

Based on available data, maternal use of anti-TNF agents is considered compatible with breastfeeding.122 Although data are limited, it is believed that the transfer of these biologics from serum to breast milk is minimal (0.1–1%).123,124 Regarding the safety of biologics or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs, while the evidence is limited, no risks have been found in infants, so their use during breastfeeding can generally be considered safe.

In all cases, healthcare providers are advised to review the drug insert for specific safety information regarding use during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Table 9 summarizes recommendations for care during these periods.

Summary of recommendations for the use of biological therapies or targeted synthetic antirheumatic drugs during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

| Recommendation | Level of agreement |

|---|---|

| 100% |

| 93% |

| 86% |

| 100% |

| 90% |

Evidence suggests an association between hypogammaglobulinemia and repeated use of drugs such as rituximab, depending on the cumulative dose.125–127 Subsequent rituximab treatments in patients have led to further reductions in immunoglobulin levels, justifying the monitoring of immunoglobulin concentrations and persistent hypogammaglobulinemia.

There is insufficient evidence regarding the measurement of immunoglobulins before initiating rituximab. However, based on clinical immunologists' experience, baseline immunoglobulin G (IgG) measurement is used as a predictor of infection risk, with subsequent measurements to assess the drug's effects. Forty-three percent of the expert panel approved baseline IgG measurement, and 79% recommended its evaluation before each rituximab cycle. This remains a controversial issue; thus, factors such as age, history of recurrent infections, and specific clinical circumstances should guide clinical judgment on the frequency of immunoglobulin testing.

Consensus updateThe need to update this consensus should be reassessed in three years or earlier if relevant evidence emerges that alters the indications. This decision will be subject to ASOREUMA considerations.

Declaration of editorial independenceThe updated consensus was developed independently, transparently, and impartially by the development group. Funding entities did not influence on the content or final document.

FinancingThis consensus was supported by three unrestricted financial contributions from Janssen Colombia, Novartis Colombia, and Abbvie SAS Colombia.

Conflict of interestConflict of interest were declared by all participants at the start of the process, before the expert consensus. Declarations are provided in Supplementary material Appendix A1, Declaration of Interests.

We would like to thank the extended panel of experts for their contributions to the discussion and final recommendations: Santiago Bernal Macias (internist, rheumatologist, epidemiology specialist), Juan Carlos Cataño Correa (internist, infectious disease specialist), Jeimmy Andrea Chaparro Sanabria (rheumatologist), Oscar Jair Felipe Díaz (internist, rheumatologist), María Constanza Latorre Muñoz (internist, rheumatologist), Diana Marcela Muñoz Urbano (rheumatologist), Jorge Luis Quinteros Barrios (internist, pulmonologist), Luis Orlando Roa Pérez (internist, rheumatologist, economics specialist), and Wilmer Gerardo Rojas Zuleta (internist, rheumatologist).