Patients with fibromyalgia experience pain at a constant and incapacitating pace. It is still a complex entity yet to be fully understood but meanwhile affects patients in every aspect of their lives.

ObjectiveThe purpose of this study is to describe what living with fibromyalgia means for Peruvian women and how it affects their family, work, and social lives in 2021.

Materials and methodsThe study has a qualitative design with a phenomenological approach; snowball sampling and theoretical saturation sample size; 10 patients were interviewed through semi-structured in-depth interviews. An ideographic and a nomothetic analysis were conducted, divergences and convergences in the statements were sought and units of analysis were obtained.

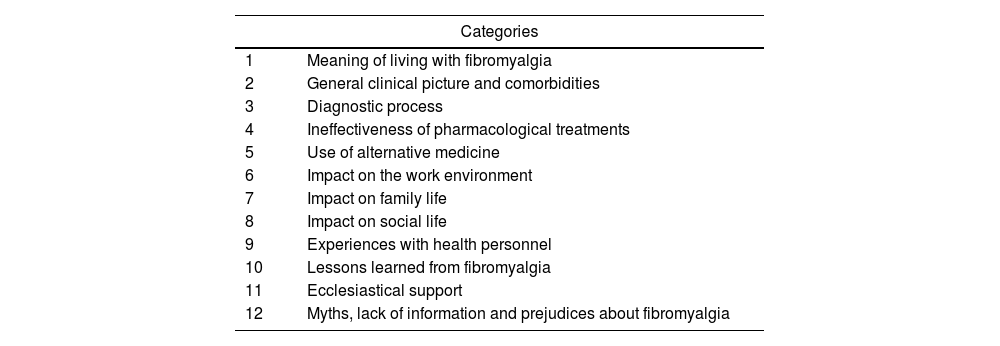

ResultsThere were 12 categories: meaning of fibromyalgia, clinical picture, complications and sequelae, diagnostic process, impact on work, impact on family life, impact on social life, experience with health personnel, lessons learned from fibromyalgia, ecclesiastical support, and myths, misinformation, and prejudices about fibromyalgia.

ConclusionThe experiences and the clinical picture are diverse, the family remains an active and reliable support network for patients, unlike social and work lives, where there is a lack of initiative or empathy towards patients. In light of our findings, we expect healthcare workers and the public in general to learn and see beyond “just histrionics” or “attention seekers” and thus improve the patient's quality of life.

Los pacientes con fibromialgia experimentan dolor a un ritmo constante e incapacitante. Esta es una entidad compleja, parcialmente comprendida, que afecta todos los aspectos de la vida del paciente.

ObjetivoEl propósito de este estudio es describir el significado de vivir con fibromialgia para las mujeres peruanas, y cómo afecta su vida familiar, laboral y social en el 2021.

Materiales y métodosDiseño cualitativo con enfoque fenomenológico; muestreo de bola de nieve y tamaño de muestra por saturación teórica; se entrevistó a 10 pacientes por medio de entrevistas en profundidad, semiestructuradas, y se aplicó un análisis ideográfico y nomotético; se buscaron divergencias y convergencias en los enunciados, y se obtuvieron unidades de análisis.

ResultadosSe encontraron 12 categorías: significado de la fibromialgia, cuadro clínico, complicaciones y secuelas, proceso diagnóstico, impacto en el trabajo, impacto en la vida familiar, impacto en la vida social, experiencia con el personal de salud, lecciones aprendidas de la fibromialgia, apoyo eclesiástico y mitos, desinformación y prejuicios sobre la fibromialgia.

ConclusiónLas experiencias y el cuadro clínico son diversos, la familia permanece como una red de apoyo activa y confiable para los pacientes, en contraste con el entorno social y laboral, que no muestran empatía hacia los pacientes. A la luz de nuestros hallazgos, esperamos que los trabajadores de la salud y el público en general aprendan y vean este problema más allá de conceptos como «solo histrionismo» o «buscadores de atención», y así mejorar la calidad de vida del paciente.

Pain is a complex concept, both for patients and for health care workers. One of the diseases in which this symptom is cardinal is fibromyalgia, which submits the patient to chronic pain and limits their social lives, work and family circles.1 It is a prevalent health problem. In Lambayeque, northern Peru, the prevalence rate was 2.99% in 20132; fibromyalgia prevalence in general population varies between 0.2 and 6.6%, in women between 2.4 and 6.8%, in urban areas between 0.7 and 11.4% and in rural areas between 0.1 and 5.2%.3

In different studies, the statements and phrases of patients are recurrent: “… there are things that I can no longer do like I used to”; these expressions show that their life is conditioned to painful crises,4 with an impact on their quality of life and mental health. On the other hand, there is well-documented evidence in relation to the limitations in physical activity and depression.5

In spite of the existence of several quality clinical practice guidelines,6,7 the response to pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment is partial; patients do not adhere to the treatment and abandon it, opting for empirical solutions or alternative therapies, which differ from patient to patient.8 Added to this is the fact that they feel misunderstood in their pain and that doctors often ignore both the diagnostic process and the own understanding of the patient.9

Patient-centred medicine and shared decision-making had proven to be a useful tool in this problem,10 as well as an adequate doctor–patient relationship,11 as the way they cope with their illness is affected by uncertainty and insecurities regarding their complex condition.12

In order for the patient to incorporate the disease into their life, it is necessary to develop coping. This process is the end result of a dichotomy dictated by self-efficacy and catastrophism. Self-efficacy is the ability of the individual to recognise his/her own strengths and skills from which he or she will take the course of action in a given situation. Catastrophism, on the other hand, conditions the magnification of pain, its redundancy and the inability to cope with it,13,14 leading the patient into a perpetual state of negativism and fear of the future.15

The interpretative meaning of each patient may vary according to the place of origin, customs, life experience, health system, among other determining factors. In Peru, for this disease, the evidence about the meaning that patients give to their ailment and how this allows them to cope successfully or catastrophically with their suffering is unknown.

This study was conceived since it is a frequent entity, with an impact on quality of life of patients, with little recognition and absence of local information that could help to understand and manage personalised care. The objective of the study was to understand the meaning of living with fibromyalgia in Peruvian female patients and how this meaning is presented in social, work and family aspects.

MethodsType and designStudy with a qualitative approach, interpretative paradigm, phenomenological type, to construct the meanings that people attribute to their experiences.

Population, sample and samplingThe population initially intended for the study were patients with fibromyalgia seen in rheumatology and/or internal medicine clinics of a high complexity hospital of the Ministry of Health in Lambayeque, Hospital Regional, in northern Peru, located through ICD 10 M79.0 during 2019 (70 patients, women were chosen instead of men for the study since prevalence is higher than among the last ones). When a group of 15 people with an address closer to the hospital were contacted by telephone, they all refused to participate. Therefore, the recruitment strategy was changed: we contacted a group of patients treated in the same hospital by the internist (FLJ), who is the researcher of this study. The first patient was contacted, from which other patients were located through communication between them (snowball sampling); the sample size was 10 participants: Lambayeque (08) (northern Peru), Piura (01) (northern Peru) and Lima (01) (central coast), a number at which thematic saturation and data redundancy were achieved. Data collection was made between January and May 2021 via Zoom videocalls. Each interview was recorded with the platform's video recording tool and then transcript to a Microsoft Word document. Also, copies of each recording and the manuscripts were uploaded to a Google Drive storage, patients gave consent before their interviews.

Exclusion criteriaNot considered for the study.

Inclusion criteriaWomen over 18 years of age, working away from home and who agreed to participate by signing the informed consent.

Data collection techniques and instruments07 semi-structured in-depth interviews (Annex 1 in the Appendix. Supplementary data) were conducted virtually via the Zoom platform and recorded in the cloud, with a 30-min duration. On the other hand, three participants answered the questions in a text sent via WhatsApp, as they did not wish to connect via Zoom or answer by telephone; for these participants, in the event of any doubts, were added as new contacts via WhatsApp to go deeper into the object of study, completing the necessary information. Field notes were obtained from the interviews and videos. The researcher in charge of the data collection (CRMJ) was a human medicine intern, with no previous contact with the patients and trained by a licenced graduate in nursing, university lecturer, qualitative researcher with expertise in phenomenology and statement analysis (RDM).

Analysis planCJRDM was in charge of the data analysis, which was manual, without the help of any software. To analyse the data, the phenomenological trajectory was followed16; everything that the patient expressed about their illness and their perception was written down in the description in order to then generate units of meaning; then, the reduction phase of the units, the ideographic analysis to delimit the repetitions or convergences in the statements, and finally the nomothetic analysis. CJRDM looked for convergences (essence in the coincidences of the people) and divergences (opposites in the subject's coincidences) that reflect the experiences of the interviewees. Finally, RDM reviewed the process and the results of the categories found.

Ethical aspectsThe principles of Elio Sgreccia's personalist ethics were considered: defence of physical life, totality, freedom and responsibility.17 At moments during the interview, when the patient was affected by recalling painful experiences, the interview was paused momentarily and she was reminded about her freedom to continue or not with the interview. Each participant was given a code consisting of the letter P, followed by a sequential Arabic numeral and finally the initials of the city of origin. An informed consent form was used (Annex 2 in the Appendix. Supplementary data) in which the confidentiality of the information, the free participation and the possibility of not answering any question were specified. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidad Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo: Annex 3 in the Appendix. Supplementary data.

ResultsThere were 10 participants; all women aged 35–59 years, five were married, three were single, two divorced; only seven had between one and three children. Their professions ranged from nurses, teachers, housewives; about comorbidities, 2/10 had hypothyroidism; none of the participants had rheumatological comorbidities.

Once the analysis of the study units was completed, they were organised into the following twelve categories (Table 1).

Categories of meaning found.

| Categories | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Meaning of living with fibromyalgia |

| 2 | General clinical picture and comorbidities |

| 3 | Diagnostic process |

| 4 | Ineffectiveness of pharmacological treatments |

| 5 | Use of alternative medicine |

| 6 | Impact on the work environment |

| 7 | Impact on family life |

| 8 | Impact on social life |

| 9 | Experiences with health personnel |

| 10 | Lessons learned from fibromyalgia |

| 11 | Ecclesiastical support |

| 12 | Myths, lack of information and prejudices about fibromyalgia |

The majority of patients expressed the meaning of “living with pain”, “coexisting” with it or learning to do so, which affects their quality of life and daily performance, from getting out of bed to putting on shoes or carrying a bag to work. “You want to be healthy, and you cannot; you learn to live with the pain […]” (P6CIX). “To live with these pains, because they will be present throughout the life of a person” (P1CIX). “It means that I live with all the symptoms permanently: chronic muscle pain, fatigue, insomnia” (P10CIX).

In some patients, the meaning varied considerably; optimistic attitudes were observed when considering the problem as an “opportunity” or “adaptation”, taking the illness as a starting point to empathise with other patients from a professional point of view, or to make changes in personal life by progressively accepting the illness. “At the same time it was a learning experience, a lecturer at the university told me to take that experience as a learning experience. I have been able to cope with it and when I have a patient with the same disease I will know how to treat it” (P5CIX).

For other patients, the experience was “something terrible” and “limiting”; one of the interviewees showed catastrophism, stating that fibromyalgia has reduced her quality of life in all aspects, to the point of being bedridden and dependent on other people on days of crisis. “It is very bad because I was processing my disability due to illness and doctors are not sensitive to illnesses that they do not know about or that they have not been taught about at the university or when they studied. It is difficult because society itself does not understand or comprehend, people think that it is about someone who does not want to do things, or does not want to socialise” (P3PIURA). “Fibromyalgia, both for me and for other patients and because we know how cruel this disease is to human beings, means limitations in many aspects of life, it changes your personal life and limits you, it is a disease that becomes a nightmare for the patient” (P7CIX).

All patients mentioned severe and permanent pain as the cardinal symptom, as well as inability to open their hands in the morning; others reported “dizziness”, “trembling”, “hot flushes”, “sleep disorders”, as well as gastrointestinal discomfort, anxiety/depression symptoms and joint pain. Some interviewees commented that after a demanding physical activity they had pain and fatigue the next day. “There are days when it is so limiting and it hurts to the tips of my hair” (P2LIM). “The day I do more, a busy day, with an activity, that day I end up exhausted, very tired, the next day I can’t get out of bed. It is not that I do not feel like it, my body just will not let me; my buttocks hurt, my shoulders, when it is time to put on shoes or walk” (P3PIURA). “Living with fibromyalgia is getting used to pain, dizziness, trembling; sometimes knowing at moments that something might happen to me, knowing that stress can lead to other illnesses” (P4CIX). “[…] Restless legs syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, osteoarthritis, anxiety […]” (P10CIX).

The presence of hypothyroidism as a comorbidity was observed in two patients.

The intensity of the pain was also variable, in some cases showing as tolerable, and in others becoming highly disabling. Also, all patients agreed that it was generalised. “Hypothyroidism also has its own thing, you have to see how to get to know this disease, learn how to handle it, learn what you have to do and also see the things that limit you so that you can cope day to day, how you are going to handle it so that everything goes smoothly and without any imbalance” (P8CIX).

The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was a long process for the patients, since it required several years and several specialists; one interviewee noted that it was “something new”; a second one mentioned being relieved to know that it was not a malignant condition. “It was concluded that it was seronegative arthritis, yes, but apart from that I had a fibromyalgia condition and that was a new term” (P7CIX). “When I was diagnosed I thanked God a lot because it is a chronic disease but not malignant. I was grateful to God. I took it calmly, but, little by little, it is progressing […]” (P4CIX).

Accepting the diagnosis involved going through different stages, from sadness and uncertainty due to disbelief about the disease, to the final acceptance, as one person described. “At the beginning, youth and ignorance made me think that the doctor was wrong […] I have gone through multiple stages: anguish, depression, intense pain, incomprehension, annoyance, anger […]” (P9CIX).

At the other extreme, for some of them, knowing their diagnosis was a relief as it showed a disease that grouped all the symptoms and was not an invention or whim of theirs. However, they also expressed uncertainty about the future, whether they would be able to stand on their own or be dependent on others. “Vindication because at last the disease I was diagnosed with encapsulated all the symptoms I was suffering from, uncertainty because they said I would have to change my pace of life and I knew little about the disease” (P10CIX).

The general opinion of the patients was that conventional pharmacological treatment was ineffective in controlling or making pain more tolerable. They also commented on the unsuccessful escalation from oral to parenteral therapy and the increasing titration of medicine doses for pain relief. On the other hand, they mentioned the increasing financial expenditure, as certain medications are not covered by their health insurance. “I control the pain with Miodel® or Tensodox®; it is not daily, but if it is handy I do not take anything, I do not want to exceed with the medication” (P4CIX). “[…] I am not very much into taking medication, I try to handle the pain to a certain extent and not make use of medication” (P7CIX). “At the end of every consultation I came out with a bag of pills and, even though it is true, they had a good effect; they also had a counterproductive one and side effects that were not good for me. So, I said: “I am either taking it or I am not”, “I am going to have to manage this dose”; you learn to manage doses and do several things in order to get better” (P8CIX).

The adverse effects of these medications are often pronounced, affecting work performance or making family activities difficult. “They started with an amount in milligrams. I got to take 350mg Cymbalta (Duloxetine), and I started with 50mg pregabalin and ended up with 200mg; then I do not remember because I was doping or they made me sleep until noon the next day” (P3PIURA).

The intention to seek alternative treatments for the ineffectiveness of painkillers and antidepressants prescribed by doctors was evident in all of them. The statements mentioned cannabis oil, natural medicines with herbs and infusions, changes in diet, vitamin and mineral supplementation, swimming, adequate rest and sleep, spirituality, electro modulation, aromatherapy, massage therapy, physiotherapy, among others. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, some patients had abandoned certain therapies due to quarantine and social distancing regulations, but tried to adapt and even get supplies to take home. “On a bad day the pain twists you and, rather than curse, I start to pray; I have a prayer called “Contemplative Prayer” and I offer Him (God) my illness to help me” (P2CIX). “Cannabis does not heal you, but it calms the pain and gives you a better quality of life. We had a talk and I have been taking cannabis oil for two years now, it does not totally calm my pain […]” (P3CIX). “[…] I take everything that is natural, including straws, nuts, quinoa, sesame, green juices and from that I try to improve things and I also listen to the music I love” (P4CIX).

In some cases, they choose to combine these alternative methods with conventional pharmacotherapy. “To treat muscle pain I sometimes take painkillers and use muscle relaxants combined with massage sessions with ointments” (P1CIX).

Concern was expressed about poor work performance due to disabling pain or the adverse effects of medication, in addition to their responsibilities such as holding high positions or having employees under their responsibility. They reported fear of being fired and having a lower family income. “At work, I was given light tasks, but even so, the workload as head of an area stresses you and contributes to exacerbating symptoms” (P9CIX). “In my professional life, I had prolonged medical breaks because of all this; it makes you think … The institution is going to say: “This person has so many medical breaks; I do not want a person like that in my staff”. All of this became a vicious circle” (P8CIX).

Moreover, several participants expressed the intention not to let the disease affect this aspect of their lives. One of the patients, however, was forced to resign her job due to the intensity of the symptoms and having had an emergency situation at work. In the case of health workers, they all agreed that they did not feel supported by their colleagues, who minimised their symptoms or simply did not believe that the disease existed, despite their training in biomedical sciences. “I have always been active, I have always worked, but there came a moment when I worked with 4 tramadols, I could not take it anymore and I fainted in the office, then I said “I cannot take it anymore”, because I could not really work” (P3PIURA). “One day they even took me out of the office to the emergency room because my chest hurt so much […]” (P3PIURA).

All patients reported strong family and, in some cases, marital support, understanding of the pain even though they could not directly objectify it. Likewise, they reported family adaptations when the interviewees could not participate in family activities or help with household chores. However, they also reported conflicts in the family when pain crises were intense. “In family life, thank God my daughters and husband understand me and try to support me in everything” (P3CIX). “My family was very supportive” (P6CIX). “With my family, I am calmed, well. When I rest a bit, the pain goes away” (P5CIX). “My young children saw me crying and cried with me, they grew up seeing me taking medication; I was worried about their interpretation of the situation (having fibromyalgia)” (P9CIX).

The main limitations that appeared in the statements were: not being able to spend time with their children, to help them with homework or to prepare them for exams, with feelings of guilt and not being “good mothers”, as well as not being able to enjoy outdoor activities, walks, or trips due to the degree of physical activity involved. “I cannot carry my grandson because I feel like he will fall or break my back or arm if I pick him up and that is frustrating. My daughter sometimes tells me “Let's go for a walk with the baby, so you can play with him in the park”, but I cannot sit and I have to stand, or carry a chair because I cannot sit on the grass and I am not that old; that is limiting and that is how I have harmed them” (P2LIM). “[…] I want to sit with the laptop, study endpoints or some PowerPoint presentations with the kids, but I feel totally bad; my husband is on his side with his remote work. I felt not like a good mum or an adequate woman, but at least I feel understood. But I do not know for how long” (P4CIX).

Social support was not homogeneous for all of them; some explained that their friends supported them in coping with the disease and forgetting the pain, and others stated that they felt misunderstood when they did not attend meetings due to pain, medical rest or simply wanting to sleep. “I was someone who went out with her friends, we toasted and I drank my liquor, the normal thing, I never smoked cigarettes; what was possible is now forbidden […] I distanced myself from my friends, many of them, sometimes they do not understand me and they think I am “vain”” (P6CIX). “When you are like that (in pain) you cannot have a social life. When there was a celebration or a birthday and they invite you to go, even if you feel in good spirits despite the pain, you think “How can I go if I am supposed to be on medical rest, I am in a poor condition”. There were a lot of things I could not do when one thing got in the way of the other”. “Socially you are limited by the fact that you have to rest early, you cannot stay awake and sleep has to be restful” (P7CIX). “Socially, everything is quiet. In fact, with them I distract myself a bit at work, I forget about the pain, and I feel better at home with my family” (P6CIX).

Most of the interviewees mentioned that, during the diagnostic process or afterwards, they had negative experiences with health personnel, due to disbelief in the existence of this problem. They expressed dissatisfaction at being constantly referred to multiple specialists, with time delays and inadequate attitudes by the personnel. “I would like doctors to be more concerned, to study more, to be more aware of this disease so that they can treat us better. I have not met any doctor that at least put themselves in our place; I do not want them to say “poor thing”, but I have met doctors who are very “strained”” (P3PIURA). “That the doctors treat us well. Sometimes you go for medicine and some of them answer us well, but not all of them. Some explain very well how to take the medication, they explain the benefits of resting, tell us to rest. Just as there are some who explain you well, there are others who do not” (P6CIX). “It is frustrating with the doctors because they took too long to reach a diagnosis, and there were many years of incomprehension, treating me like a paranoid lunatic and having had symptoms of everything and in the end nothing” (P2LIM). “I remember going to an orthopaedic specialist, he told me it was not fibromyalgia. I felt bad. You feel in the air, it would be good that a doctor by chance say “Let us study, what else do you have”, but he just dismissed it and said “You are faking it and you come here wanting me to give you a medical break”. I did not want a medical break, I wanted him to treat me, to give me a treatment” (P8CIX).

The little empathy shown towards them could increase uncertainty, either before or after the diagnosis, and the lack of understanding makes them feel undervalued. Only one patient mentioned that, just as there are doctors who do not show any interest in the patients or any understanding of the disease, there are also those who take the time to explain to the patient the reason for her symptoms and clarify other doubts in the outpatient clinic.

10. Lessons learned from fibromyalgiaWithin the limitations encountered in many aspects of their lives, there are participants who were able to obtain certain lessons learned from this disease. Even though it is recognised that they have abandoned activities or are not able to do things at the same pace as before, there is a gain and it is reflected in the desire to support other patients with the same diagnosis, both on a personal and professional level, as well as the acquisition of new values, such as resilience. “Resilience would be the most adequate, you have to learn to make the best of this situation” (P8CIX). “At the same time it was a learning experience, a lecturer at the university told me to take that experience as a learning experience. I have been able to cope with it and when I have a patient with the same disease I will know how to treat it” (P5CIX).

In addition, the recognition that this disease has no cure, but rather control, evidences a certain level of resignation. “It would be to find the medicine for this disease, several doctors who have treated me tell me that there is no cure” (P6CIX).

Faith and spirituality, offering the pain to God, contribute to a certain extent to let patients to cope with their pain by giving it a meaning linked to the religion they profess, where they no longer act according to their own will, but according to the will of God and his infinite wisdom. “The Church has helped me a lot, I belong to the Neocatechumenal Way and we are a vertex of the Catholic Church, we are catechists and responsible for a community, and, in this, the Lord is the one who has helped us as a family to accept the precariousness of health, and them as Christian children (his children) not to abandon their parents in conditions of old age or illness” (P2LIM). “Our strength is that we are Catholic, we have a spiritual priest and he speaks to us. That priest said that fibromyalgia and those who suffer from it are a bit distant from the Lord, that it is very different to go to mass than for you to pray and fulfil the commandments of the Lord to the full. Not only did I hear the priest say that, but another person from the Church said that maybe I have an emptiness […] But the main thing is the spiritual part, that is what encapsulates everything as a fundamental pillar; having God is everything, if we have him close to us, he strengthens us” (P4CIX).

The interviewees expressed that in their environment there was a lot of misinformation about this health problem, which contributes to the minimisation of the symptoms.

This discourages patients, who not only have to deal with generalised pain, asthenia and other symptoms, but also with the disbelief of others, being labelled as “actresses” who want medical breaks from work. “Socially, people still believe that (fibromyalgia) is a story, that you are lying, that you say “I have fibromyalgia” and they look at you, they are silent; I mean, do they ignore or criticise? I think they criticise or they put a label on you “This lady is crazy” [laughs] It is an assumption” (P9CIX). “In the beginning, when I wanted to be heard, I clearly remember a colleague who shouted: “How is it possible that she's in pain, if I see her stunning! I hardly see this credible”. I am not one to complain because if I get tired, I ask; other colleagues may get tired and my tiredness is just a little more […] I felt a little misunderstood at that moment by that colleague and even doctors, what they say to you feels like mockery. “Here comes the pain lady” “But doctor, I want you to listen to me, I have this …”” (P4CIX). “You go on the internet to look for information about this disease. There is a lot to discuss, to read, to know a bit more. There is still a gap” (P7CIX). “Spreading about the disease for people to know about it is very important, this way they understand what you go through and learn to accept your symptoms and that you got fibromyalgia; it is not that you are faking it, you are not making it up” (P8CIX).

Fibromyalgia is a disease that presents different nuances and permanently modifies the life of a person. It disrupts aspects of their lives and eventually, patients come to accept it as part of their lives. Acceptance of the pain can reduce pain intensity, disability, anxiety and depression18; however, this aspect is not seen in these patients. Psychological flexibility, through acceptance and commitment to cope with the disease, improves their lives.19 Psychotherapy has demonstrated to improve their pain, mental health and disability.20,21 It is striking that the term “psychotherapy” appears only tangentially in the statements. The support of psychologists/psychiatrists was not mentioned and perhaps, this finding could mean a “medicalisation” of this disease, which requires an interdisciplinary approach with the support of mental health professionals. Likewise, physical therapy (massage therapy) was only tangentially mentioned in the statements as a component of their treatments. The various clinical practice guidelines6,7 recommend its inclusion as a fundamental tool in the management and prognosis.21 This finding is a reason for further research and investigation.

The meaning of the disease was described in all patients, the most common being “learning to live with the pain”. In spite of its multiple upheavals and limitations, knowing that it would be permanent and partially limiting allows them to design different strategies to cope with it.22

Some interviewees expressed frustration at not being able to carry out household chores or participate with other family members, which makes them feel excluded. Briones et al. approach this specific type of limitation from a historical gender perspective, in which the woman is profiled as the one responsible for the household par excellence, taking care of everyone and maintaining order; failure to do so generates feelings of uselessness and comparisons with healthy women, as well as comments from third parties and feeling that they have no control over their lives.4

A very important aspect was the relief of knowing what their condition was. This is a very important starting point in the concept of self-care or self-management. In chronic diseases, it enables individuals to control their health status and to make effective behavioural, cognitive and emotional responses necessary for a satisfying life throughout their lives.23 Knowing what they have, learning to handle and accept it, and knowing the triggers that can generate symptoms, is very important.

The partial efficacy of the pharmacological component is widely described.24 Adverse effects, cost and lack of health insurance coverage may increase anxiety. The drowsiness produced by the different schemes can potentially alter their quality of life. This reality was noted in the participants.

An interesting finding was the use of alternative medicine. In relation to the use of herbs, in a meta synthesis from 2021, Tsiogkas et al., in seven studies analysing the efficacy of garlic, ginger, turmeric, cinnamon and saffron in various rheumatic diseases, including fibromyalgia, found that the methodological quality and bias of the studies did not allow a conclusion of proven usefulness.25

One patient mentioned the use of “herbs”. The reference to cannabis as a treatment alternative is striking. Khurshid et al., in a systematic review of 22 studies (observational and experimental), found that a significant analgesic effect was observed in several of them, with few adverse effects. However, they mention that the types of cannabinoids, the form of presentation, the long-term effect, the treatment time and the dependency possibilities did not allow their definitive inclusion in the therapeutic arsenal yet.26 Another systematic review of 10 studies and 1.136 patients found that medical cannabis could be beneficial for some people with this condition, but that more studies are needed to confirm efficacy, the most effective type of cannabis to use and how the clinical results would be evaluated.27 In our country, the use of this type of treatment for this condition is not authorised. It is an interesting line of research that can be explored.

On the other hand, aerobic exercise28 was also mentioned in the statements, although only by a few interviewees. It has been shown to be effective in palliating pain, improving mood and sleep. The structuring of these therapeutic alternatives by the health services in hospitals of the Ministry of Health in our country is far from being organised. The “fragmentation” of the patient or the search for these alternatives in private entities by the patient is a limitation that must be considered.

Adequate family support was observed in all the interviewees, which is consistent with the findings of other studies,29 in which the family circle is sympathetic to the suffering of the patients and adapts to their new needs. Family support is fundamental and it is important to promote it within health service programmes. However, it is also important to approach the family, as there is evidence that in more than 50% of patients, there is a negative impact on the relationships between the patient and the partner and with other family members.30 This is another alternative to be studied.

In the social and work circles, the same kind of willingness to listen, care, understand or adapt to the new routines or needs of the interviewees was not shown, and inadvertently, people around them do not believe in their symptoms. They need to understand that they are part of their support network and should be as involved as family members.31 Lack of information about the disease and mechanistic/biological concepts of the disease contribute to this.

The same was evident with health personnel and their role in the diagnostic process and subsequent handling of fibromyalgia. Several studies show a lack of support and disbelief in the existence of fibromyalgia, to the point of categorising them as “problematic” or “exaggerated” women, considering that patients go to doctors in order to be heard and obtain a diagnosis.32 Briones, in a Spanish qualitative study in 2018, found three categories of responses in interviews with health care providers: a. “Fibromyalgia patient: the woman who complains”, b. “It is a health problem of women, and men are a privileged minority”, and c. “The attitude of the providers revolved around the question Are they really suffering or faking it?”.33

On the other hand, 3/10 of the patients were nursing graduates, and their statements show the incomprehension of their colleagues. It is possible that a mechanistic/biomechanical view of illness by health science personnel contributes to thinking that someone who “looks good” or whose ancillary tests are “normal” cannot be ill.34 Also, as one of the patients interviewed expressed, there are doctors who are a hopeful contrast, who recognise patients as such and do not fall into stigma.35

The path to diagnosis was long for all patients; most of them were referred to different specialists without getting answers and being medicated with analgesics with partial relief of the pain experienced. Diagnostic delays of up to 23 years have been reported.9 Mistreatment and stigmatisation by healthcare personnel and patient uncertainty about their condition can cloud the prognosis.29,35

The terms “learning” and “resilience” also appeared in the statements. Both terms, especially the latter, have been studied in these patients; in fact, their presence allows these patients to cope with the burden of this disease with tools learned in the past.36 One possibility is that patients, faced with the chronicity of their symptoms, seek out information that is now widely available and may have learned this terminology.

The spiritual approach to fibromyalgia handling was present during the interviews; some patients found prayer and the Catholic religion to be the support they needed to cope with the disease. Religion emerged as another support network, something that contributes to coping with the disease and provides greater life satisfaction.37 This finding was common in our study; however, there is evidence from another study that found negative correlations between spirituality with physical role and emotional role scores on the SF-36 quality of life questionnaire.38 These findings probably need to be explored in a qualitative-quantitative study.

The limitations of the study include that in some of the interviews people did not turn on the cameras during the interview, not appreciating body language or facial gestures as they narrated their experiences. Another limitation is that in 4/10 of the interviews, WhatsApp was used for the answers to the in-depth questions. While it is true that we cannot speak of “bias”, this could lead to differences in the data collection. In this respect, there is evidence of the use of these technologies in the times in which we live, both in quantitative and qualitative studies such as this study.39,40 Social distancing, travel bans and other restrictions have had practical implications for the traditional method of face-to-face data collection. New technology has also paved the way for exploring alternative data collection methods for conducting qualitative interviews. This quick transition has been made possible by a rapid process of digitisation, which has accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, qualitative interviews conducted via video, telephone and online are valid and reliable alternatives to traditional face-to-face interviews. Furthermore, these interview methods could reform the notion that face-to-face interviews are the gold standard, as interviews conducted remotely serve their purpose in a more cost-effective manner while promoting inclusiveness and equality in research.40

Another limitation to mention is that the interpretation of the data was done by a single researcher and that the credibility criterion (where the results are contrasted with the participants) was not met.

Finally, we must also mention that the magnification of symptoms in patients may appear in the context of a pandemic, due to fear of infection and social isolation with activation of neuro-humoral mechanisms or related to a SARS cov2 infection, which has been found to produce very similar rheumatological symptoms, even in recovered patients.41 This must be kept in mind for future research to explore the best ways to approach and care for these patients.

ConclusionsFibromyalgia holds a complex and diverse range of meanings. Experience varies among patients, and the clinical onset, as well as symptoms differ. “To live with pain” becomes something common, directly or indirectly surging during the interviews and constitutes the near future vision for the disease. A particular contrast was witnessed as fibromyalgia was taken as an opportunity to help and empower people going through the same process. Whilst the family sphere becomes a safety network for most patients, the social and work spheres show themselves unwilling to believe the patient and have a null display of flexibility, even when the pain becomes too much to be physically bearable. Healthcare workers become part of the problem, as well, given the lack of empathy and the quick dismissal of the patient, regarding fibromyalgia as “Non-existent” or just histrionics. Conventional medication has proven to be partial effective, on the other side, alternative therapies (massages, swimming, exercise, cannabis oil) end up being patient's main choice to deal with pain and other symptoms. By making this research, we expect local practitioners to start paying concern to fibromyalgia and stop dismissing patients who already put up pain and criticism and resort to a medical consult looking for answers that, sometimes, take up to years to be found.

NoteThis work was part of the Thesis to obtain the Graduate Degree in Medicine of Consuelo Matilde Rivera-Miranda Giral. It can be found in the digital repository of Universidad Católica Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo at url: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12423/4573.

Authors’ contributionsCRMJ: conceptualised the idea, collected data, wrote the first version of the manuscript, reviewed the last version of the manuscript; RDM: conceptualised the idea, collected data, reviewed the last version of the manuscript; FLJ: conceptualised the idea, supervised the research team, reviewed the last version of the manuscript.

Ethical approvalThe interviewed patients gave their informed consent for the study and publication of the final manuscript. The study was evaluated and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo Catholic University with the resolution: No. 066-A-2022-USAT-FMED, Chiclayo, May 17, 2022.

FundingThis article has been financed with the authors’ own resources.

Conflict of interestThe authors deny having conflicts of interest.

To all the patients who participated in this study.