To describe health-related QOL (HRQOL) in patients with musculoskeletal symptoms, compared to a population with other comorbidities, and a healthy population.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was carried out on an open population involved in a community-oriented program for control of rheumatic diseases (COPCORD) study in Colombia, using EQ-5D-3L for estimating QOL, and the health assessment questionnaire disability index (HAQ-DI) for functional capacity.

ResultsOut of the total 4020 individuals evaluated, 2274 had rheumatic diseases, 642 had non-rheumatic diseases, and 1104 were healthy subjects. Spondyloarthritis (SpA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients had more complaints regarding pain/discomfort and mobility. As for daily activities, the diseases that mostly affected them were systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and RA. RA and fibromyalgia (FM) patients had the worst scores as regards anxiety/depression and self-care dimensions. FM patients had the lowest QOL measured by EQ-VAS (57.7±26.2).

The most frequent non-rheumatic diseases were cardiovascular and mental disorders, with 20% of these patients having a moderate level of pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression.

The rheumatic patients reported a decrease in functional capacity (HAQ: 0.49), in contrast to the healthy population (0.01), and the population having other diseases (0.06).

ConclusionRheumatic disease patients in Colombia had the worst QOL compared to the healthy population and patients with other comorbidities. Rheumatic patients had greater functional limitations, even more so when having comorbidities. This study revealed potential factors of interest requiring the attention of public health authorities, and for improving patients’ QOL.

Describir la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en pacientes con síntomas musculoesqueléticos, en comparación con pacientes con enfermedades no reumáticas y una población sana.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio transversal en comunidad abierta, en personas involucradas en un programa orientado a la comunidad para el control de enfermedades reumáticas (COPCORD) en Colombia, utilizando el EQ-5D-3L para estimar la calidad de vida y el cuestionario de evaluación de la salud (HAQ- DI) para la capacidad funcional.

ResultadosSe evaluaron 4.020 individuos; 2.274 tenían enfermedades reumáticas, 642 tenían enfermedades no reumáticas y 1.104 eran sujetos sanos. Los pacientes con espondiloartritis (SpA) y artritis reumatoide (AR) tuvieron mayores quejas con respecto al dolor/malestar y la movilidad. En cuanto a las actividades diarias, los enfermos con lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) y AR fueron los más afectados. Los pacientes con AR y fibromialgia (FM) tuvieron las peores puntuaciones en ansiedad/depresión en las dimensiones de cuidado personal. Los pacientes con FM tuvieron la calidad de vida más baja medida por EQ-VAS (57,7±26,2).

Las enfermedades no reumáticas más frecuentes fueron los trastornos cardiovasculares y mentales; el 20% de estos pacientes tenía un nivel moderado de dolor/malestar y ansiedad/depresión.

Los pacientes reumáticos reportaron una disminución de la capacidad funcional (HAQ: 0,49); en contraste con la población sana (0,01) y la población con otras enfermedades (0,06).

ConclusiónLos pacientes con enfermedades reumáticas en Colombia tuvieron la peor calidad de vida en comparación con la población sana y los pacientes con otras enfermedades. Los pacientes reumáticos tuvieron una mayor limitación funcional, incluso más que los que tenían otras enfermedades. Este estudio reveló posibles factores relacionados con las enfermedades reumáticas que requieren la atención de las autoridades de salud pública con el objetivo de mejorar la calidad de vida de los pacientes.

Musculoskeletal (MSK) and connective tissue diseases represent a group of disorders having differing demographic, genetic and clinical features; they are characterized by pain and chronic inflammation, affecting the locomotor system, often being accompanied with generalized autoimmune phenomena-derived systemic involvement. Rheumatic diseases are the most commonly occurring chronic non-communicable diseases worldwide.1 The group is formed by around 200 entities including joint diseases, connective tissue diseases, spinal problems, soft tissue rheumatism with regional or generalized pain, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis.

Rheumatic diseases are the main cause of disability and quality of life (QOL) impairment in the Western hemisphere, significantly increasing economic costs/burden and absenteeism from work.2 Several sequelae are the result of advanced stages of the disease or as a product of the clinical flare-ups frequently accompanying them.3 The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study stated that 2112 deaths occurred in Colombia during 2013 as a consequence of rheumatic diseases (655 males and 1457 females).4 Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) statistics for 2013 stated that rheumatic disease patients’ life expectancy was 7.44 years lower than that established for cardiovascular diseases (86.35 years), making rheumatic diseases the fifth group (regarding 23 diseases analyzed) having lower life expectancy. Average loss regarding healthy life expectancy (HALE) was 46.65 years; even more so, this group of diseases occupies the second place concerning “priority causes of death” in Colombia.5

The Community Oriented Program for the Control of Rheumatic Diseases (COPCORD) is an epidemiological strategy designed to identify, prevent and control rheumatic diseases in developing countries; it was created by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR).6 Its use enables identifying potential intervention factors as public health strategies. A prevalence study of rheumatic diseases in a population over 18 years-old was carried out in Colombia (2014 to 2016) using an instrument for identifying patients having MSK symptoms. The study surveyed an open population in six Colombian regions; it included QOL and functional capacity questionnaires (i.e. the health assessment questionnaire disability index – HAQ-DI).7

This study describes health-related QOL (HRQOL) in patients with musculoskeletal symptoms, compared to a population with other comorbidities and a healthy population.

Patients and methodsThis was a cross-sectional, analytical study designed for people over 18 years-old. A probabilistic stratified sampling method involved using three stages. The first sampling stage consisted of selecting cartographic areas in each city, as defined by the Colombian National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE, Departamento Adminístrativo Nacional de Estadística). The second sampling stage involved blocking each sector using an urban analysis tool which classifies cities into blocks, houses, households and people (VIHOPE). The third stage concerned the homes in each block; all household members were surveyed. The sample size was calculated at 6528 individuals for a 1.5 sampling design effect and 14% sampling error.

The COPCORD questionnaire,8 adapted for Colombia, was used during the first stage by standardized interview.9 EQ-5D-3L was used for estimating health status and the HAQ-DI for measuring functional capacity.10 All individuals over 18 years old with non-traumatic symptoms of muscle pain, swelling, painful or joint stiffness, in the last seven days or on any occasion in their life were included in the study.

The EQ-5D is a generic instrument which estimates QOL and health status regarding five dimensions: mobility, self-care, habitual activities, pain or discomfort and anxiety or depression.11 Each dimension has three response categories (no problems, some or moderate problems and extreme problems). A patient's overall health status is rated on a vertical, visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) ranging from 0 to 100mm.12

The measurement of functional capacity was carried out using the HAQ-DI instrument that measures the functional capacity of patients in the last week. It is a self-applied questionnaire composed of 20 questions, which are synthesized in 8 categories, being the major functional limitation 3 and no limitation 0.13

All patients underwent a direct interview by trained interviewers using a structured form previously validated and culturally adapted to the Colombian population. The patients were informed about the objective of the study and the results that were intended to be obtained. If the patient agreed to participate in the study, an informed consent was signed. Patients who had rheumatic symptoms were evaluated by a rheumatologist who established whether or not a defined rheumatic disease was present.

For the estimation of the QOL and functional limitation were included a total of 4020 individuals evaluated since May 2014 until June 2016. The final diagnosis was done by a group of internists and rheumatologists.

The group of rheumatic disease was defined using the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for the most frequent entities: osteoarthritis (OA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), gout, fibromyalgia (FM), systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) and spondyloarthritis (SpA). Patients having rheumatic symptoms secondary to Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection were confirmed by IgG or IgM serological assays. The rheumatic regional pain syndromes (RRPS), classification proposed by Alvarez-Nemegyie, was used for diagnosing soft-tissue rheumatism, including tendinopathies, bursopathies, entrapment neuropathies and enthesopathies not associated with systemic disease.14,15 The term non-specific musculoskeletal disease (NSMD) was used for describing pain symptoms, inflammation or stiffness of some skeletal muscle structure not classified into the previous categories. The study was a transversal observation, so the disease activity measures in rheumatic patients are lacking.

Other comorbidities without rheumatic diseases were categorized as “non-rheumatic diseases patients” according to the ICD-10 registry. Specifically, high blood pressure (HBP), diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer, tuberculosis (TB), psychiatric disorders, obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, stroke, epilepsy and migraine.

In case that patients with rheumatic disease had another comorbidity, they were grouped as “rheumatic disease and comorbidities”. The control group was classified as disease-free individuals, when a disease was ruled out.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc, version 22.0) was used for data analysis. Frequencies were calculated for nominal and categorical variables; measures of central tendency (mean) and dispersion (standard deviation) were determined for continuous variables. To compare the differences between groups the t-Student, U-Mann–Whitney, Wilcoxon or ANOVA were used according to the characteristics of variables. A p<0.05% statistical significance with 95% confidential interval (95%CI) were used.

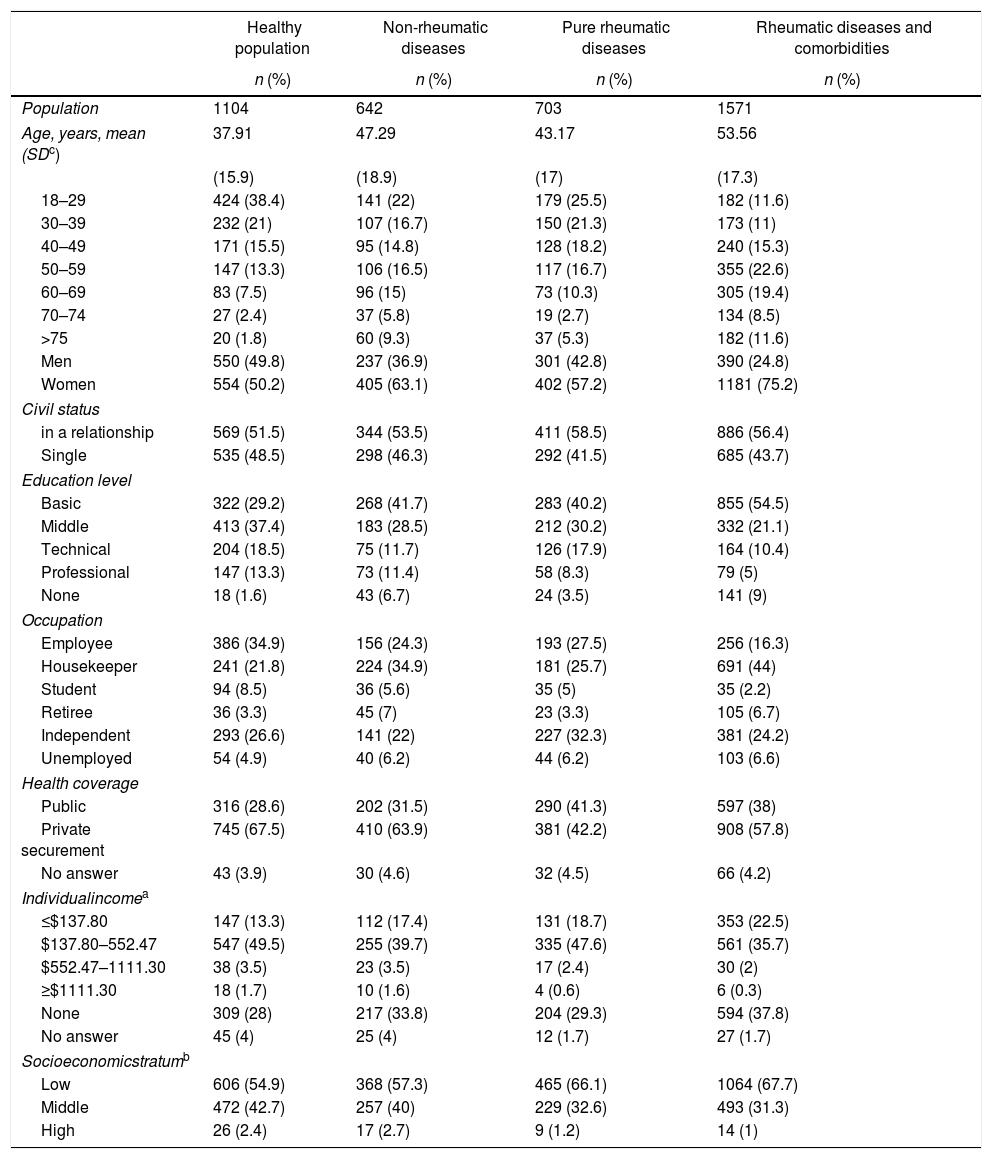

ResultsRheumatic diseases were confirmed in 2274 (57%) out of the total of 4020 individuals evaluated for this study; 642 (16%) were diagnosed as suffering from non-rheumatic diseases and 1104 (27%) were excluded and classified as healthy population. Interestingly, 69% (n=1571) of patients suffering from rheumatic diseases had one or more comorbidities. The majority of the population were women, in a relationship, with an educational level between basic and middle. Almost more than de 50% had a low socioeconomic stratum. There were no significant differences between the population groups (Table 1).

Sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of the adult Colombian population: COPCORD population.

| Healthy population | Non-rheumatic diseases | Pure rheumatic diseases | Rheumatic diseases and comorbidities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Population | 1104 | 642 | 703 | 1571 |

| Age, years, mean (SDc) | 37.91 | 47.29 | 43.17 | 53.56 |

| (15.9) | (18.9) | (17) | (17.3) | |

| 18–29 | 424 (38.4) | 141 (22) | 179 (25.5) | 182 (11.6) |

| 30–39 | 232 (21) | 107 (16.7) | 150 (21.3) | 173 (11) |

| 40–49 | 171 (15.5) | 95 (14.8) | 128 (18.2) | 240 (15.3) |

| 50–59 | 147 (13.3) | 106 (16.5) | 117 (16.7) | 355 (22.6) |

| 60–69 | 83 (7.5) | 96 (15) | 73 (10.3) | 305 (19.4) |

| 70–74 | 27 (2.4) | 37 (5.8) | 19 (2.7) | 134 (8.5) |

| >75 | 20 (1.8) | 60 (9.3) | 37 (5.3) | 182 (11.6) |

| Men | 550 (49.8) | 237 (36.9) | 301 (42.8) | 390 (24.8) |

| Women | 554 (50.2) | 405 (63.1) | 402 (57.2) | 1181 (75.2) |

| Civil status | ||||

| in a relationship | 569 (51.5) | 344 (53.5) | 411 (58.5) | 886 (56.4) |

| Single | 535 (48.5) | 298 (46.3) | 292 (41.5) | 685 (43.7) |

| Education level | ||||

| Basic | 322 (29.2) | 268 (41.7) | 283 (40.2) | 855 (54.5) |

| Middle | 413 (37.4) | 183 (28.5) | 212 (30.2) | 332 (21.1) |

| Technical | 204 (18.5) | 75 (11.7) | 126 (17.9) | 164 (10.4) |

| Professional | 147 (13.3) | 73 (11.4) | 58 (8.3) | 79 (5) |

| None | 18 (1.6) | 43 (6.7) | 24 (3.5) | 141 (9) |

| Occupation | ||||

| Employee | 386 (34.9) | 156 (24.3) | 193 (27.5) | 256 (16.3) |

| Housekeeper | 241 (21.8) | 224 (34.9) | 181 (25.7) | 691 (44) |

| Student | 94 (8.5) | 36 (5.6) | 35 (5) | 35 (2.2) |

| Retiree | 36 (3.3) | 45 (7) | 23 (3.3) | 105 (6.7) |

| Independent | 293 (26.6) | 141 (22) | 227 (32.3) | 381 (24.2) |

| Unemployed | 54 (4.9) | 40 (6.2) | 44 (6.2) | 103 (6.6) |

| Health coverage | ||||

| Public | 316 (28.6) | 202 (31.5) | 290 (41.3) | 597 (38) |

| Private securement | 745 (67.5) | 410 (63.9) | 381 (42.2) | 908 (57.8) |

| No answer | 43 (3.9) | 30 (4.6) | 32 (4.5) | 66 (4.2) |

| Individualincomea | ||||

| ≤$137.80 | 147 (13.3) | 112 (17.4) | 131 (18.7) | 353 (22.5) |

| $137.80–552.47 | 547 (49.5) | 255 (39.7) | 335 (47.6) | 561 (35.7) |

| $552.47–1111.30 | 38 (3.5) | 23 (3.5) | 17 (2.4) | 30 (2) |

| ≥$1111.30 | 18 (1.7) | 10 (1.6) | 4 (0.6) | 6 (0.3) |

| None | 309 (28) | 217 (33.8) | 204 (29.3) | 594 (37.8) |

| No answer | 45 (4) | 25 (4) | 12 (1.7) | 27 (1.7) |

| Socioeconomicstratumb | ||||

| Low | 606 (54.9) | 368 (57.3) | 465 (66.1) | 1064 (67.7) |

| Middle | 472 (42.7) | 257 (40) | 229 (32.6) | 493 (31.3) |

| High | 26 (2.4) | 17 (2.7) | 9 (1.2) | 14 (1) |

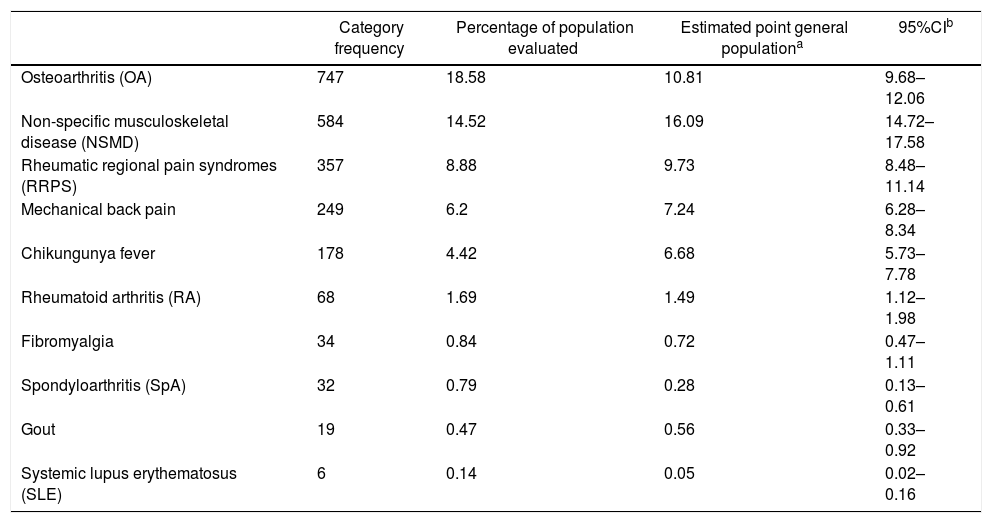

The most frequent rheumatic disease was OA, followed by NSMD (Table 2).

Frequencies regarding the categories of the people/patients evaluated in six Colombian cities.

| Category frequency | Percentage of population evaluated | Estimated point general populationa | 95%CIb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis (OA) | 747 | 18.58 | 10.81 | 9.68–12.06 |

| Non-specific musculoskeletal disease (NSMD) | 584 | 14.52 | 16.09 | 14.72–17.58 |

| Rheumatic regional pain syndromes (RRPS) | 357 | 8.88 | 9.73 | 8.48–11.14 |

| Mechanical back pain | 249 | 6.2 | 7.24 | 6.28–8.34 |

| Chikungunya fever | 178 | 4.42 | 6.68 | 5.73–7.78 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | 68 | 1.69 | 1.49 | 1.12–1.98 |

| Fibromyalgia | 34 | 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.47–1.11 |

| Spondyloarthritis (SpA) | 32 | 0.79 | 0.28 | 0.13–0.61 |

| Gout | 19 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.33–0.92 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) | 6 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.02–0.16 |

Inference population: rheumatic disease prevalence study of people over 18 years of age in Colombia. Sample size 6528. ** RRPS: rheumatic regional pain syndromes: rotator cuff tendinopathy, shoulder bicipital tendinopathy, lateral and medial epicondylalgia, Quervain's tendinopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, Dupuytren's contracture, trochanteric syndrome, anserine bursitis, Achilles tendonopathy, plantar talalgia.

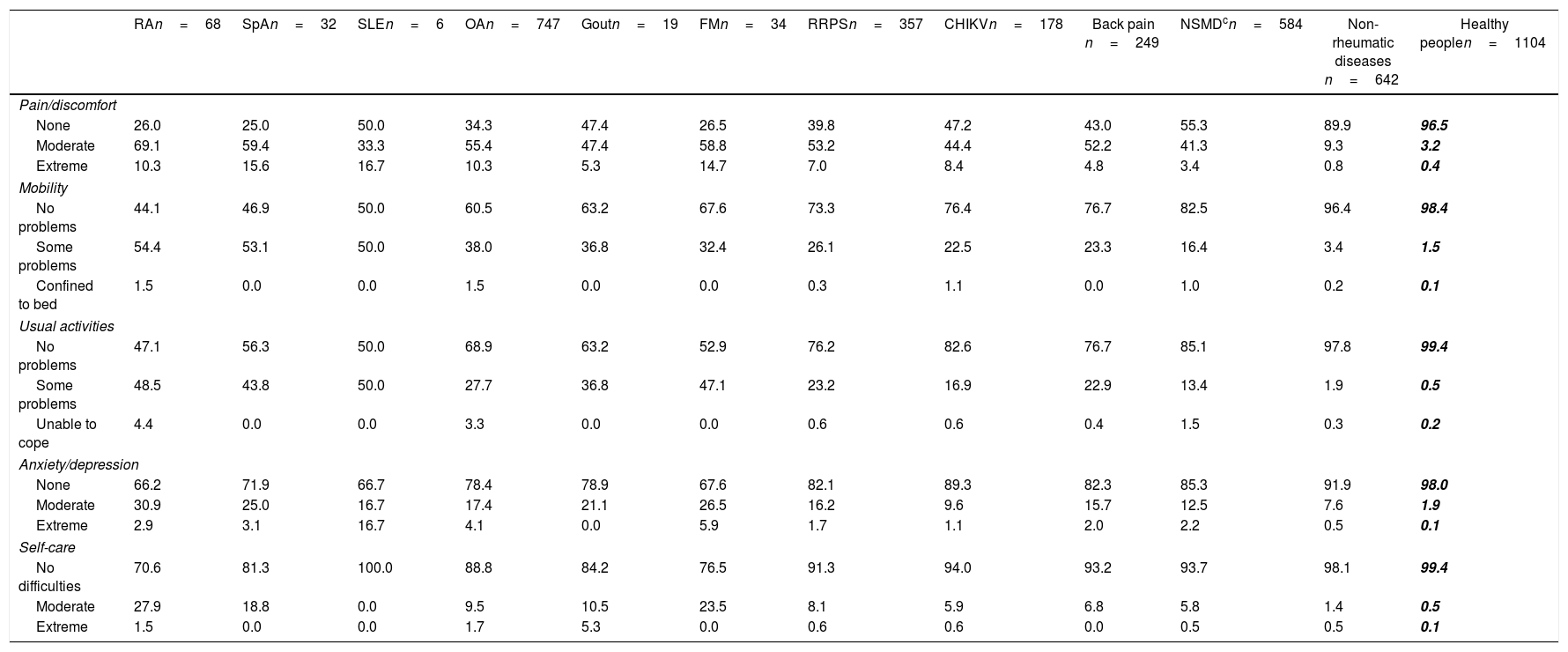

Regarding the five domains of the EQ-5D-3L instrument, only 25% of SpA and 26% of RA patients had no pain or physical discomfort compared to the disease-free population and patients having other pathologies (p<0.0001). In the mobility item, 98.4% of the disease-free people interviewed did not report any walking problems, while more than 50% of RA and SpA patients stated having some problems with mobility (p<0.000). Almost all healthy people experienced no difficulty in performing daily activities; however, around 50% of RA and SLE patients reported having some problems (p<0.000). In terms of anxiety and depression, FM (32.4%), RA (33.8%) and SLE (33.4%) patients were the most affected, this being statistically significant when compared to disease-free people (p<0.000). RA (29.4%) and FM (23.5%) patients experienced moderate difficulties regarding personal care when compared to disease-free people (p<0.000) (Table 3).

Quality of life (QOL) measured by EQ-5D-3La regarding rheumatic and non-rheumatic patients and healthy people (open population study).b

| RAn=68 | SpAn=32 | SLEn=6 | OAn=747 | Goutn=19 | FMn=34 | RRPSn=357 | CHIKVn=178 | Back pain n=249 | NSMDcn=584 | Non-rheumatic diseases n=642 | Healthy peoplen=1104 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain/discomfort | ||||||||||||

| None | 26.0 | 25.0 | 50.0 | 34.3 | 47.4 | 26.5 | 39.8 | 47.2 | 43.0 | 55.3 | 89.9 | 96.5 |

| Moderate | 69.1 | 59.4 | 33.3 | 55.4 | 47.4 | 58.8 | 53.2 | 44.4 | 52.2 | 41.3 | 9.3 | 3.2 |

| Extreme | 10.3 | 15.6 | 16.7 | 10.3 | 5.3 | 14.7 | 7.0 | 8.4 | 4.8 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Mobility | ||||||||||||

| No problems | 44.1 | 46.9 | 50.0 | 60.5 | 63.2 | 67.6 | 73.3 | 76.4 | 76.7 | 82.5 | 96.4 | 98.4 |

| Some problems | 54.4 | 53.1 | 50.0 | 38.0 | 36.8 | 32.4 | 26.1 | 22.5 | 23.3 | 16.4 | 3.4 | 1.5 |

| Confined to bed | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Usual activities | ||||||||||||

| No problems | 47.1 | 56.3 | 50.0 | 68.9 | 63.2 | 52.9 | 76.2 | 82.6 | 76.7 | 85.1 | 97.8 | 99.4 |

| Some problems | 48.5 | 43.8 | 50.0 | 27.7 | 36.8 | 47.1 | 23.2 | 16.9 | 22.9 | 13.4 | 1.9 | 0.5 |

| Unable to cope | 4.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Anxiety/depression | ||||||||||||

| None | 66.2 | 71.9 | 66.7 | 78.4 | 78.9 | 67.6 | 82.1 | 89.3 | 82.3 | 85.3 | 91.9 | 98.0 |

| Moderate | 30.9 | 25.0 | 16.7 | 17.4 | 21.1 | 26.5 | 16.2 | 9.6 | 15.7 | 12.5 | 7.6 | 1.9 |

| Extreme | 2.9 | 3.1 | 16.7 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| Self-care | ||||||||||||

| No difficulties | 70.6 | 81.3 | 100.0 | 88.8 | 84.2 | 76.5 | 91.3 | 94.0 | 93.2 | 93.7 | 98.1 | 99.4 |

| Moderate | 27.9 | 18.8 | 0.0 | 9.5 | 10.5 | 23.5 | 8.1 | 5.9 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| Extreme | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

a Q-5D-3L dimension values are expressed in %.

b COPCORD: community-oriented program for the control of rheumatic diseases.

c RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SpA: spondyloarthritis; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; OA: osteoarthritis; FM: fibromyalgia; RRPS: rheumatic regional pain syndromes (rotator cuff tendinopathy, shoulder bicipital tendinopathy, lateral and medial epicondylalgia, Quervain's tendinopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, Dupuytren's contracture, trochanteric syndrome, anserine bursitis, Achilles tendonopathy, plantar talalgia); NSMD: non-specific musculoskeletal disease; non-rheumatic diseases: HBP, DM, cardiovascular disease, cancer, TBC, psychiatric disorders, obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, stroke, epilepsy, migraine.

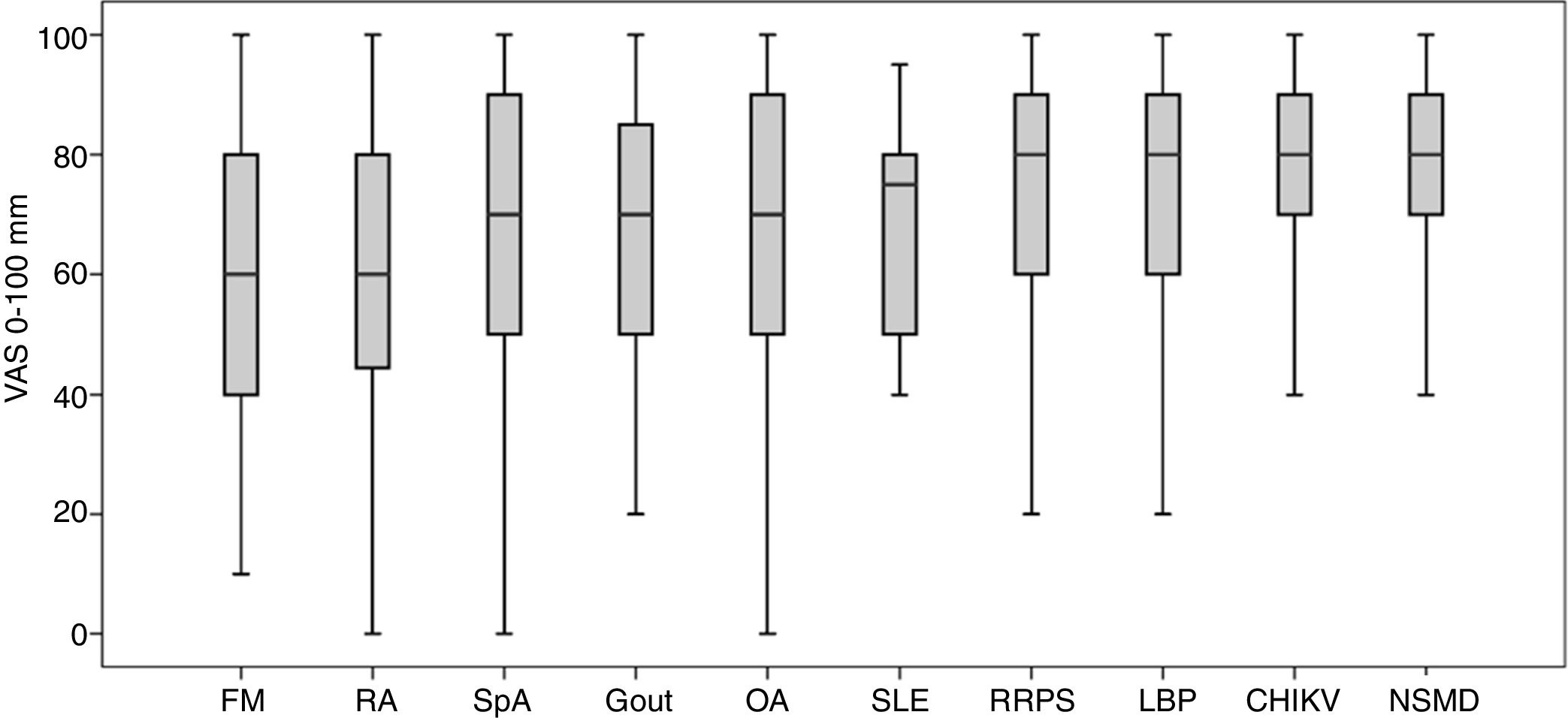

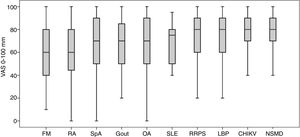

The EQ-5D-3L estimated FM patients as having the worst QOL (57.7±26.2), followed by RA patients (59.8±24.7). Fig. 1 shows the results for all groups of patients analyzed by EQ-5D-3L (Fig. 1).

Rheumatic patients’ QOL in Colombia estimated by EQ-5D-3L: 0–100mm. FM: fibromyalgia, RA: rheumatoid arthritis, SpA: spondyloarthritis, OA: osteoarthritis, SLE: generalized lupus erythematosus, RRPS: rheumatic regional pain syndromes, CHIKV: Chikungunya fever, NSMD: non-specific musculoskeletal disease.

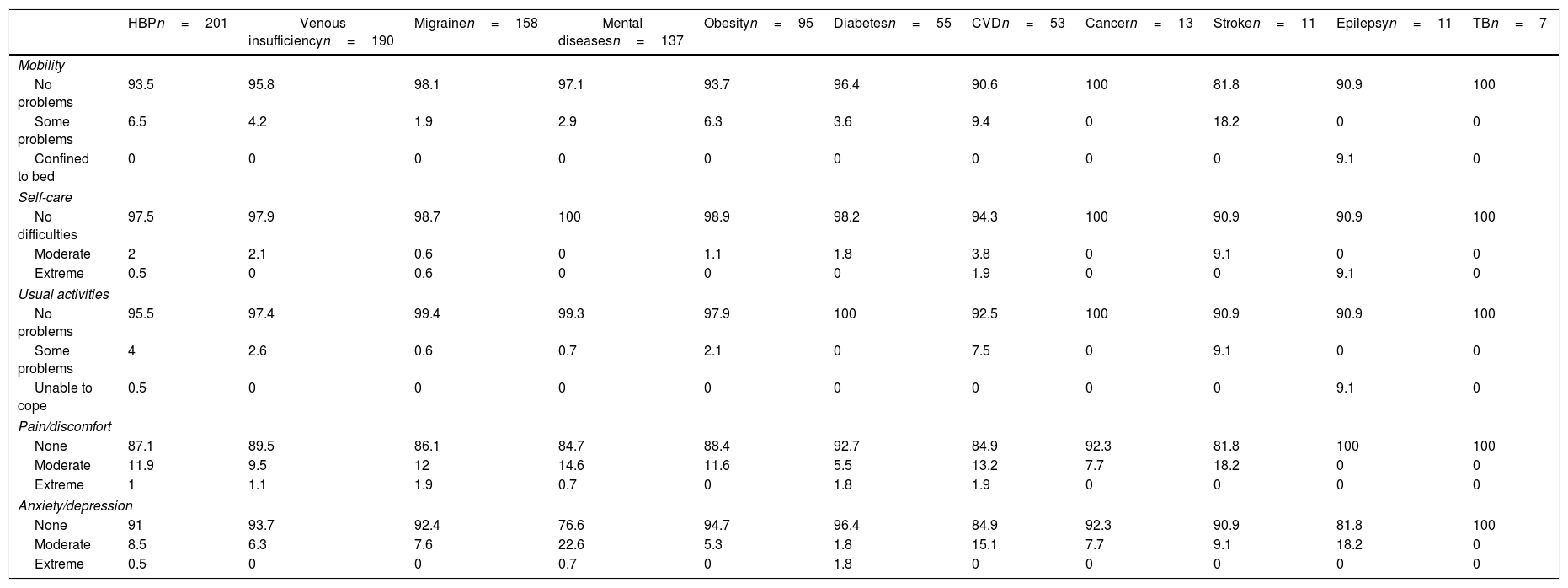

The main non-rheumatic diseases found in the open population studied were HBP, venous insufficiency, migraine and mental disorders. Regarding EQ-5D-3L dimensions, 20% of these group of patients reported moderate involvement of pain and physical discomfort as well as anxiety and depression, 20% of patients suffering from CVD reported moderate mobility limitation and 10% of epilepsy patients had severe compromise. Patients suffering from cardiovascular diseases reported moderate difficulty in carrying out daily activities (Table 4).

EQ-5D-3L dimensions regarding patients suffering non-rheumatic comorbidities.

| HBPn=201 | Venous insufficiencyn=190 | Migrainen=158 | Mental diseasesn=137 | Obesityn=95 | Diabetesn=55 | CVDn=53 | Cancern=13 | Stroken=11 | Epilepsyn=11 | TBn=7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility | |||||||||||

| No problems | 93.5 | 95.8 | 98.1 | 97.1 | 93.7 | 96.4 | 90.6 | 100 | 81.8 | 90.9 | 100 |

| Some problems | 6.5 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 6.3 | 3.6 | 9.4 | 0 | 18.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Confined to bed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.1 | 0 |

| Self-care | |||||||||||

| No difficulties | 97.5 | 97.9 | 98.7 | 100 | 98.9 | 98.2 | 94.3 | 100 | 90.9 | 90.9 | 100 |

| Moderate | 2 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 0 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 0 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Extreme | 0.5 | 0 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | 9.1 | 0 |

| Usual activities | |||||||||||

| No problems | 95.5 | 97.4 | 99.4 | 99.3 | 97.9 | 100 | 92.5 | 100 | 90.9 | 90.9 | 100 |

| Some problems | 4 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 0 | 7.5 | 0 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Unable to cope | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.1 | 0 |

| Pain/discomfort | |||||||||||

| None | 87.1 | 89.5 | 86.1 | 84.7 | 88.4 | 92.7 | 84.9 | 92.3 | 81.8 | 100 | 100 |

| Moderate | 11.9 | 9.5 | 12 | 14.6 | 11.6 | 5.5 | 13.2 | 7.7 | 18.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Extreme | 1 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 0 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anxiety/depression | |||||||||||

| None | 91 | 93.7 | 92.4 | 76.6 | 94.7 | 96.4 | 84.9 | 92.3 | 90.9 | 81.8 | 100 |

| Moderate | 8.5 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 22.6 | 5.3 | 1.8 | 15.1 | 7.7 | 9.1 | 18.2 | 0 |

| Extreme | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

EQ-5D-3L dimension values are expressed in %.

a HBP: high blood pressure, CVD: cardiovascular disease, TB: tuberculosis.

b Mental disorders: anxiety, nervousness or depression.

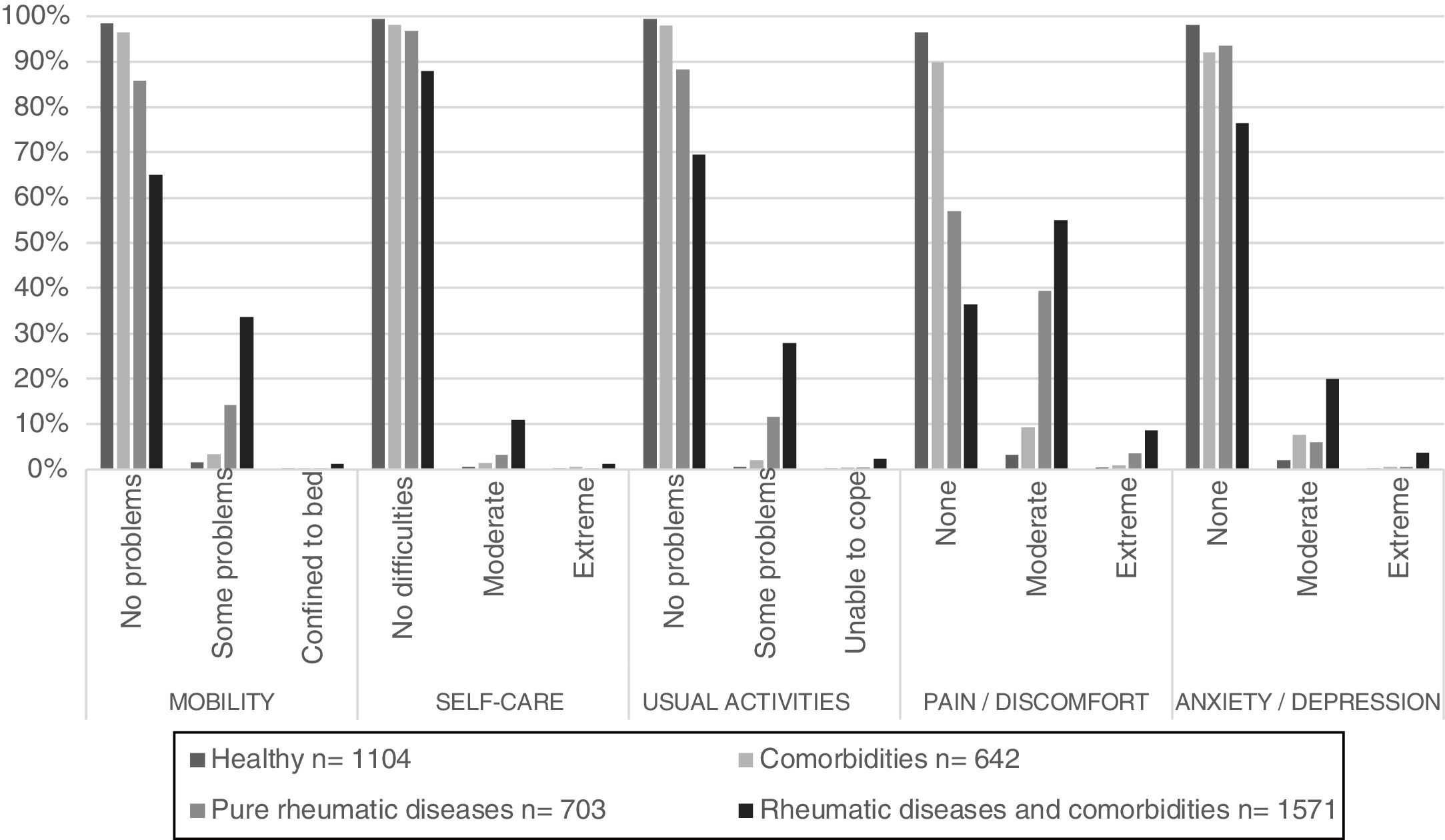

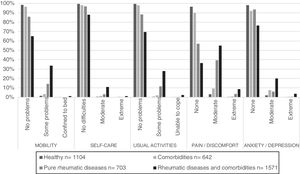

Reported QOL for the healthy population and patients having non-rheumatic diseases followed a very similar pattern. Patients suffering from rheumatic diseases and comorbidities had greater QOL involvement, predominately regarding pain and physical discomfort, moderate difficulty being documented in more than 50% of the patients (Fig. 2).

EQ-5D-3L regarding patients suffering comorbidities, rheumatic diseases and healthy people. Pure rheumatic diseases: RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SpA: spondyloarthritis; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; OA: osteoarthritis; FM: fibromyalgia; RRPS: rheumatic regional pain syndromes (rotator cuff tendinopathy, shoulder bicipital tendinopathy, lateral and medial epicondylalgia, Quervain's tendinopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, Dupuytren's contracture, trochanteric syndrome, anserine bursitis, Achilles tendonopathy, plantar talalgia); NSMD: non-specific musculoskeletal disease ** Comorbidities: HBP, DM, cardiovascular disease, cancer, TBC, psychiatric disorders, obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, stroke, epilepsy, migraine.

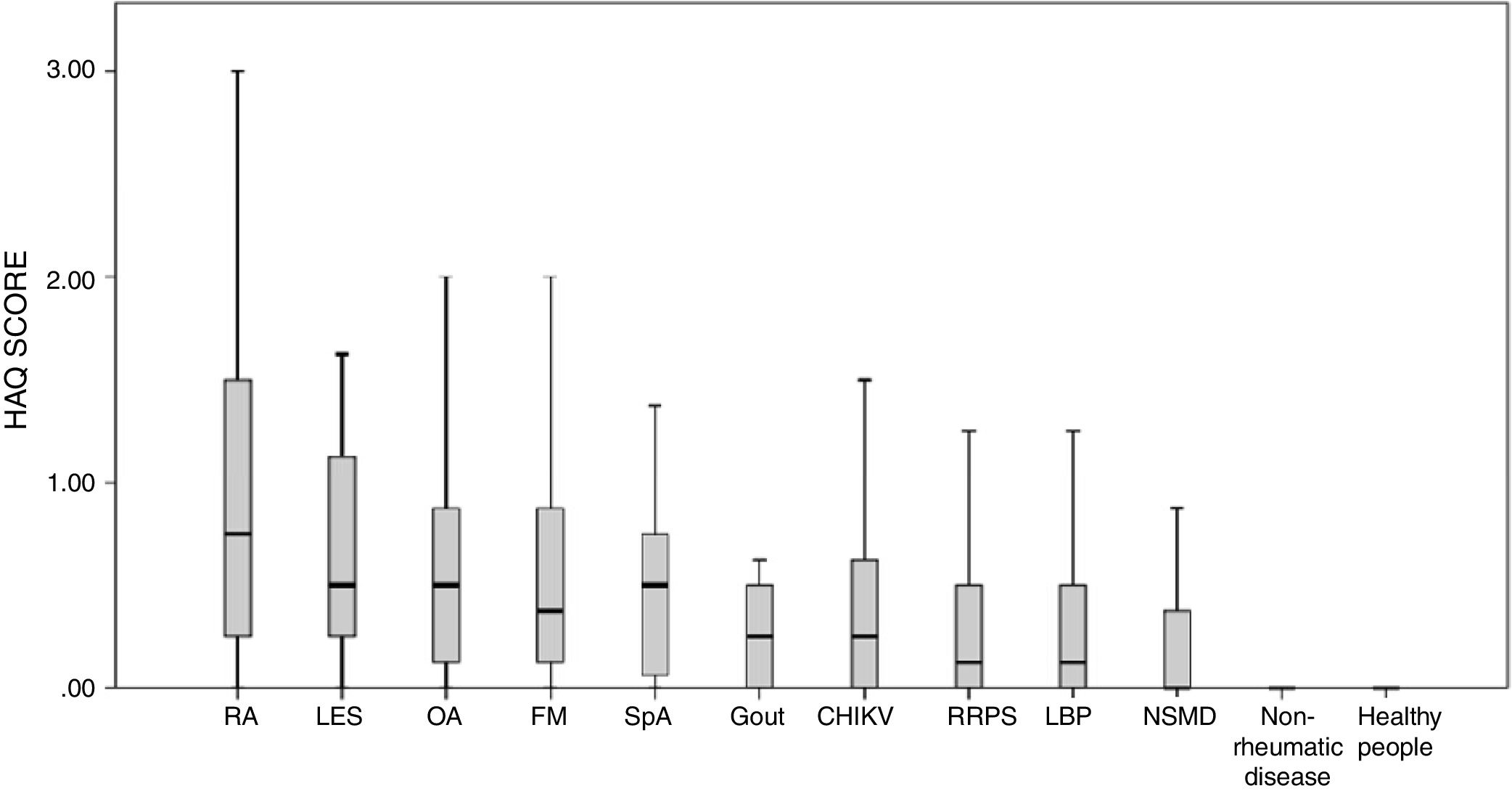

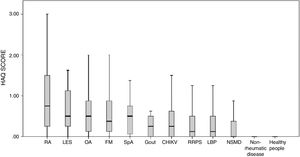

HAQ-DI results revealed that rheumatic disease patients had a higher degree of functional limitation than disease-free people and non-rheumatic patients. RA patients’ score was 0.88±0.72 compared to 0.06±0.22 for non-rheumatic diseases and 0.01±0.14 for healthy people. The HAQ-DI score for the remaining diseases was 0.67 (SD±0.62) for SLE, 0.59 (SD±0.58) for OA, 0.56 (SD±0.57) for FM and 0.52 (SD±0.43) for SpA. Rheumatic patients suffering comorbidities had a mean HAQ-DI score of 0.50±0.55 (Fig. 3).

Rheumatic disease and non-rheumatic disease patients and the healthy population's functional capacity (HAQ-DI scores). ** RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SpA: spondyloarthritis; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; OA: osteoarthritis; FM: fibromyalgia; RRPS: rheumatic regional pain syndromes (rotator cuff tendinopathy, shoulder bicipital tendinopathy, lateral and medial epicondylalgia, Quervain's tendinopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, Dupuytren's contracture, trochanteric syndrome, anserine bursitis, Achilles tendonopathy, plantar talalgia); NSMD: non-specific musculoskeletal disease; LBP: low back pain. ** Non-rheumatic diseases: high blood pressure, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, TB, mental disorders, obesity, venous insufficiency of lower limbs, stroke, epilepsy, migraine.

According to the five dimensions evaluated by EQ-5D-3L, healthy and non-rheumatic patients had a good state of health compared to rheumatic patients. Rheumatic disease patients reported deterioration regarding the following aspects: pain/physical discomfort, mobility and daily activities.

The use of the EQ instrument in rheumatic diseases is limited. As far as our knowledge goes, the available studies are from countries with economic and social differences compared to our country, factors that can influence the results. Goulia et al. documented pain, functional limitations and psychological disorders being independently associated with physical QOL in a population of younger and older Greek patients suffering from chronic rheumatic diseases. The impact of pain was higher in the young population, having greater psychosocial consequences.16 Pain, functional limitation, anxiety, depression and the presence of comorbidities were the actors associated with poor QOL in a population of Greek rheumatic patients described by Anyfanti et al.17

Rheumatic disease patients (particularly RA patients) had the lowest QOL measured by EQ-5D-3L in our research; SpA and SLE patients closely followed them. Similar findings regarding HRQOL perception have been reported in other studies. Inflammatory arthritis patients have been evaluated in the United Kingdom and they classified their disease as having low health status by HRQOL. Pain was the predominant deterioration factor regarding QOL in this group; patients often scored states as being “worse than death” on the EQ-5D.18

A similar study of rheumatic disease prevalence was carried out in Portugal in adults over 18 years-old (21.2% prevalence); rheumatic disease patients had low EQ-5D-3L scores regarding all dimensions. Such marked QOL deterioration was directly related to anxiety symptoms and HAQ scores were significantly high. Rheumatic diseases had a high impact on patients’ QOL and functional capacity, as in our results, though polymyalgia rheumatica patients had the worst QOL in this population, having higher scores than those for inflammatory diseases such as RA and SLE.19

There has been growing interest in Colombia in studying rheumatic disease-related QOL using instruments validated and reproduced in other countries. Regarding RA, the disease activity impact was studied through a questionnaire in 2003 using the Quality of Life-Rheumatoid Arthritis (QOL-RA) scale. Depression, disability, pain, anxiety and low QOL symptoms were associated with RA activity regardless of age, gender and/or illness duration. Depression was directly correlated with anxiety, pain and disability and inversely correlated with QOL; such results indicated that RA activity significantly affected the patients’ state of mental health, QOL and family dysfunction. The authors proposed a holistic conception as a fundamental part of RA patients’ therapy (20).20 However, Colombian RA patients’ had a better QOL regarding all QOL-RA dimensions compared to that of participants in studies from the USA (of both Anglo-Saxon and Latin American origin).21

Colombian SLE and FM patients’ deterioration regarding anxiety and depression aspects is striking. Meszaros et al., published meta-analysis results in 2012, reporting a 39% depression prevalence, making this one of the most frequently occurring clinical manifestations of central nervous system involvement in SLE patients. The authors also related the origin of anxiety and depression to the moment of diagnosis being confirmed.22

The Short Form 36 (SF-36) health survey/questionnaire was used with a group of female Japanese SLE patients in 2015; it was found that such SLE patients had poorer QOL due to physical role deterioration, overall health perception, social functioning and emotional health. Sleep disturbance had a greater impact on the emotional domain (OR: 10.7 1.88–61.1 95%CI, p=0.008), this being higher than that related to chronic organic damage which mainly affected physical aspects.23

Colombian SLE patients’ perception of their disease has been explored recently using the focus group analysis technique. Most patients revealed negative consequences concerning all aspects of their lives, having some degree of temporary or permanent limitation affecting their daily activities or even justifying absenteeism. This research described an external perception (family, healthcare providers or work environment) which patients “simulated” and, socially, only recognized their disease state when reaching critical conditions. Progress toward a holistic biopsychosocial conception/vision was thus emphasized to optimize such patients’ QOL.24 The poor relationship between activity index-evaluated disease improvement and SLE patients’ perspective of their well-being has previously been described; HRQOL improvement should thus be considered an integral part of established treatments’ effectiveness.25

Another SF-36-based study involving a sample of Colombian SLE patients demonstrated a QOL deterioration produced by the disease, pain being the symptom having the greatest impact (without reducing anxiety and depression symptoms’ importance).26

Our EQ-5D-3L results revealed that FM patients were classified as having the worst QOL, worse than for inflammatory disease patients (i.e. RA, SpA and SLE); such findings were consistent with previous studies in Colombia.27,28 HRQOL has been assessed on 171 FM patients in the USA using EQ-5D-31. These patients had the worst QOL regarding other conditions related to generalized chronic pain, i.e. related to functional impairment due to pain, poor sleep pattern, lower productivity, greater comorbidities, greater chronic use of analgesics and increased costs.29 FM has thus been proposed as a complex dimensional disorder, rather than a simple representation of chronic pain so as to involve considering the impact on these patients’ QOL, especially regarding aspects related to physical function, fatigue and associated mental disorders involving depression and/or anxiety.30

Pain and discomfort accounted for the most frequently occurring alterations considering the OA patients evaluated in our research (55.4%), greater than that for other dimensions such as mobility and the performance of daily activities. These findings were similar to the results of a study involving a sample of the Cuban population. Patients suffering pain secondary to OA of the hip and knee were rated as having the worst QOL.31 Results similar to ours have been reported in Australian (71.3mm EQ-5D)32 and North American population samples (74.4±16.7 EQ-5D).33

Another aspect considered in our research was using HAQ to evaluate functional limitations produced by rheumatic diseases. Rheumatic patients generally had limitations on their mobility and ability to perform daily activities. The mean amount of rheumatic patients was 0.49, higher than that recorded in the disease-free population (0.01) and the population suffering from other non-rheumatic diseases (0.06). RA patients had the greatest functional limitation (0.88 HAQ) followed by SLE and OA. Our results/scores were similar to those reported for the aforementioned Portuguese population,19 greater than those for Peruvian patients’ functional limitation recorded in a COPCORD stage 1 study (0.38)34 and lower than those described for a Brazilian COPCORD study (BRAZCO) (1.09).35 The progression of rheumatic patients’ functional limitation related to aspects specific to the disease and systemic complications must be considered; disability related to these diseases is directly related to early death, greater socioeconomic impact and incapacity for work.36

Physical disability regarding rheumatic diseases is influenced by cognitive, affective and behavioral factors related to the way in which patients manage pain- and fear-associated depression.37 Taking into account the strong association between depression and physical and psychological QOL, effective therapeutic interventions should include comprehensive rehabilitation models combining both physical and psychological aspects as the only way to improve the patients’ QOL.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first population study using EQ-5D for estimating HRQOL regarding Colombian rheumatic patients. Such patients had the worst QOL and greater deterioration concerning functional capacity; it was thus inferred that this population group would be associated with greater healthcare service consumption. This study's results will facilitate developing models for estimating the economic impact in relation to the burden of rheumatic diseases in Colombia, a fundamental element for reducing healthcare inequity and designing intervention strategies through primary and secondary prevention programs for patients’ welfare and that of their environment.

Our study had some limitations regarding the reduced systemic disease sample size (i.e. SLE secondary to its low prevalence in the open population) and the absence of EQ-5D-3L reference values for the Colombian population.

ConclusionsColombian patients suffering from rheumatic diseases had a significant decrease in QOL and functional capacity compared to that for the general population. Such deterioration was greater in rheumatic patients suffering from cardiovascular comorbidities and psychiatric disorders. RA patients’ mobility was the most affected, as was their ability to perform daily activities and all stressed the accompanying pain and discomfort. Factors susceptible to intervention must be recognized in the comprehensive care of patients suffering from rheumatic diseases to improve QOL standards and reduce long-term functional limitations.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThe project was approved by the Universidad de La Sabana Faculty of Medicine's research subcommittee and ethics committee (Code MED-191-2015). All patients included in the study signed an informed consent form. Information confidentiality was maintained following Declaration of Helsinki principles.

Availability of data and materialsAll complementary information including forms, databases, tables and secondary statistical analyses are available to interested parties. Please do not hesitate to contact the authors.

Funding statement and disclosuresThis study had the financial support of the Asociación Colombiana de Reumatología (Acta N° 156, May 31, 2014), and La Universidad de La Sabana, which guarantees the complete realization of the project. All other authors declare no conflicts.

Consent for publicationAll the authors have known and reviewed the manuscript and have given their authorization for the submission and publication.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflicts of interest. No financial support or benefits from commercial sources, or any additional conflict of interest exist with regard to this work.