Raynaud's phenomenon (RP) is an exaggerated vascular response to cold or stress that is manifested by changes in skin colour. It can be primary (PR) or secondary (SR).

ObjetivesThe objective of this systematic review of the literature (SLR) is to describe and analyse the main differences for the detection of vascular changes in RP between capillaroscopy (NC) and infrared thermography (IRT).

MethodsAn SLR following PRISMA guidelines in the following information sources: Medline, Cochrane, Pubmed, ClinicalKey and ScienceDirect. Inclusion criteria: observational or analytical articles published until September 2020, that included a population with RP (primary or secondary), with concomitant diagnostic evaluation using NC (microscopic or videocapillaroscopy) and IRT. In the construction of the search equations, MeSH terms (“Thermography”, “Microscopic Angioscopy”) and different keywords crossed with different Boolean operators were used. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in Systematic Reviews Checklist was used to assess the risk of bias. The SWiM guideline was followed to synthesize and present the results.

Results1397 articles were identified, of which, after screening and eligibility, five were included. They included different populations, evaluated with different equipment; two articles in children and three in adults. Predominantly Caucasian and female population, total of 403 individuals (79 minors). The two studies carried out in the paediatric population showed non-concordant results and the studies in the adult population showed similarities in their results (NC better discriminates PR from SR), but with different connective tissue pathologies associated with SR.

ConclusionsMicrovascular findings from two diagnostic tools (NC and IRT) are presented through the SLR when used concomitantly in RP. Through the 5 articles, it is not possible to conclude that there are clear differences or advantages/disadvantages in the preferential use of one of the two diagnostic techniques in RP, highlighting the value of NC for differentiating between PR and SR. Further studies are required to analyse differences between the two techniques.

El fenómeno de Raynaud (FR) es una respuesta vascular exagerada al frío o al estrés que se manifiesta por cambios de coloración de la piel; puede ser primario (RP) o secundario (RS).

ObjetivosEl objetivo de esta revisión sistemática de la literatura (RSL) es describir y analizar las principales diferencias para la detección de cambios vasculares en FR entre la capilaroscopia (NC) y la termografía infrarroja (TRI).

MétodosRSL siguiendo guías Prisma en las siguientes fuentes de información: Medline, Cochrane, Pubmed, ClinicalKey y ScienceDirect. Criterios de inclusión: artículos publicados hasta septiembre del 2020, observacionales o analíticos, que incluyeran población con FR (primario o secundario), con evaluación diagnóstica concomitante utilizando NC (microscópica o videocapilaroscopia) y TRI. En la construcción de las ecuaciones de búsqueda se utilizaron términos MeSH («Thermography», «Microscopic angioscopy») y diferentes «Keywords» cruzadas a través de diferentes operadores boleanos. Se utilizó la herramienta «Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in Systematic Reviews Checklist» para evaluar el riesgo de sesgo. Se siguió la guía SWiM para sintetizar y presentar los resultados.

ResultadosSe identificaron 1.397 artículos, de los que luego de cribado y elegibilidad, se incluyeron cinco. Contemplaron poblaciones diferentes, evaluadas con equipos diferentes, dos artículos en niños y tres artículos en adultos. La población fue predominante caucásica y de género femenino, en total 403 individuos (79 menores de edad). Los dos estudios realizados en población pediátrica presentan resultados no concordantes y los estudios en población adulta presentan similitudes en sus resultados (NC técnica diagnóstica que mejor discrimina RP de RS), pero con patologías del tejido conectivo asociadas a RS diferentes.

ConclusionesA través de RSL se presentan hallazgos microvasculares de dos herramientas diagnósticas (NC y TRI) cuando se utilizan de manera concomitante en el FR. No se puede concluir a partir de los cinco artículos que existan diferencias claras o ventajas/desventajas en el uso preferente de una de las dos técnicas diagnósticas en el FR; el valor de la NC destaca para la diferencia entre RP y RS. Se requieren nuevos estudios para analizar diferencias entre las dos técnicas.

Raynaud's phenomenon (RP) manifests with episodes of transient spasms of peripheral blood vessels, most often in response to cold. Characteristically, it presents three distinct phases comprising paleness, cyanosis, and erythema. This symptom may be accompanying some autoimmune diseases in Raynaud's syndrome. It is important to analyse the changes and evolution over time with the inclusion of new technologies in the diagnostic methods available for this phenomenon.1

There are different techniques available for the diagnosis of RP, some with higher costs, and others that offer the possibility of performing the diagnosis in the office, such as very low-cost portable systems. Nailfold capillaroscopy (NC) provides a non-invasive window into microcirculation and allows early identification of an underlying disorder in the patient presenting with RP. This is a simple, safe, and inexpensive method for the detailed study of circulation in a wide range of diseases. In NC, the highlighted techniques are conventional or microscopic and videocapillaroscopy.1 In RP, it not only allows a precise study of capillary circulation but also enables the distinction between primary and secondary RP.2,3

However, a new diagnostic tool is currently being used: thermography (IRT). This is a low-cost portable system that uses an infrared camera to identify skin temperature in different parts of the hands, measuring the radiation that is emitted according to micro- and macro vascularization.4

Recent studies have demonstrated the reliability of quantitative assessment using high-power videocapillaroscopy, although it is mandatory to ensure that the same segment of folds is examined on each occasion.5 However, it is relevant to establish the advantages and disadvantages of NC with IRT, since the latter is a low-cost test and is also easily accessible as it can be performed even during rheumatology consultation.

The recent development of low-cost thermography may lead to its increasing use. New versions of thermal imaging cameras can be connected to devices that potentially allow for thermal imaging by the rheumatologist in the clinic rather than in a specialized laboratory. However, there are caveats: mobile cameras have wider limits of accepted accuracy (i.e., the temperature recorded by mobile devices may be further from the "real" temperature by up to ±5% compared to ±1% for more specialized devices) and imaging in an outpatient clinic would not allow for the same sIRTct environmental standardization of a specialized laboratory.6–8

However, if these considerations are taken into account and mobile cameras are accepted as a method for rapid screening, to establish (for example) the existence of "negative" temperature gradients (fingertips are colder than the back of the hand) at standard level/room temperature, then thermography could be added to the base of the available evidence to the clinician in outpatient practice.5–7

It is important to review the existing literature to generate an academic resource that may be useful so that other working groups in the scientific community can assess the benefits and guide the proper use of these diagnostic methods, adapted to the needs and assistance of patients according to available resources.

Therefore, this systematic review of the literature aims to describe and analyse the microvascular findings and the main differences in the detection of RP between capillaroscopy and thermography.

Materials and methodsStudy type and designA systematic review of the literature.

PopulationDescriptive and analytical articles that met the selection criteria published in the following databases were included: Medline, Cochrane, ClinicalKey, Pubmed, and ScienceDirect. The age of the participants was not considered an exclusion criterion.

PICOP: patients with Raynaud's phenomenon

I: diagnosis by capillaroscopy

C: diagnosis by thermography

O: microvascular findings of the two tests

Selection criteriaInclusion criteriaResearch articles published until September 2020. Clinical IRTals, observational, cross-sectional, cohort, case-control, longitudinal studies, case series, and case reports, in humans that included populations with the following disease: RP (primary or secondary), with mention of these diagnostic evaluations: NC (microscopy or videocapillaroscopy) and IRT.

Exclusion criteriaAnimal models, in vitro vascular or cultures, narrative reviews, letters to the editor, book chapters, systematic reviews, and studies that included patients with different types of RP in which it was not possible to differentiate the diagnostic tests performed or their results, and the absence of comparison between NC and IRT.

Information sourcesA systematic review of the literature was conducted with a predetermined search strategy not limited to a database (Medline, Cochrane, Pubmed, ClinicalKey, ScienceDirect). Information from a secondary source was considered and the search pattern was sIRTctly followed to reduce the possibility of selection bias, as well as to have the possibility of replicating the search pattern by other researchers.

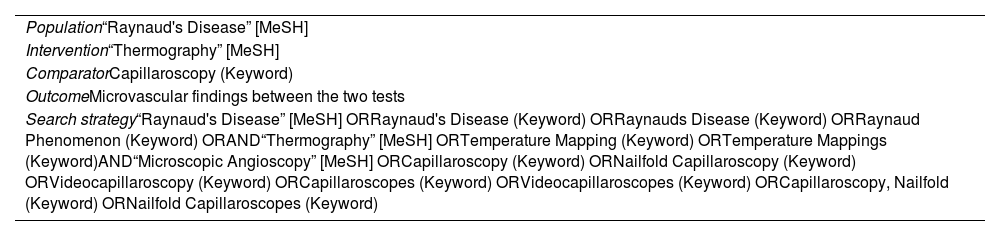

The search was carried out with a deadline of September 30, 2020. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms “Thermography” and “Microscopic angioscopy” were used. The keywords were included considering that population or diagnostic test with no MesH term according to the main objective of the search, and, in turn, to allow to find a greater number of articles to be screened in those cases in which an established MeSH term was already found.

In the construction of the search equations, each of the MeSH terms was crossed with the respective “Keywords”, using different Boolean operators (OR, AND, NOT) (see Table 1). Likewise, a gray literature search was applied. Study identification was not resIRTcted by language, age, or country of origin, yet the search was limited to humans. Abstracts and full-text articles were considered.

Search equation according to MeSH terms.

| Population“Raynaud's Disease” [MeSH] |

| Intervention“Thermography” [MeSH] |

| ComparatorCapillaroscopy (Keyword) |

| OutcomeMicrovascular findings between the two tests |

| Search strategy“Raynaud's Disease” [MeSH] ORRaynaud's Disease (Keyword) ORRaynauds Disease (Keyword) ORRaynaud Phenomenon (Keyword) ORAND“Thermography” [MeSH] ORTemperature Mapping (Keyword) ORTemperature Mappings (Keyword)AND“Microscopic Angioscopy” [MeSH] ORCapillaroscopy (Keyword) ORNailfold Capillaroscopy (Keyword) ORVideocapillaroscopy (Keyword) ORCapillaroscopes (Keyword) ORVideocapillaroscopes (Keyword) ORCapillaroscopy, Nailfold (Keyword) ORNailfold Capillaroscopes (Keyword) |

The following search arms were combined:

((((Raynaud's Disease [MeSH Terms])) OR (Raynaud's Disease)) OR (Raynaud's Disease)) OR (Raynaud's Phenomenon).

((Thermography [MeSH Terms]) OR (Temperature Mapping)) OR (Temperature Mappings).

(((((((Microscopic Angioscopy [MeSH Terms]) OR (Capillaroscopy)) OR (Nailfold Capillaroscopy)) OR (Videocapillaroscopy)) OR (Capillaroscopes)) OR (Videocapillaroscopy)) OR (Capillaroscopy, Nailfold)) OR (Nailfold capillaroscopes).

Information gathering techniquesThe information was collected from a secondary source, in the following order, according to the Prisma9 guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analysis, considering the phases of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion: first, a search pattern was created according to the previously described strategy in Table 1; second, this search pattern was run independently by the two authors, in the following databases: Medline, Cochrane, Pubmed, ClinicalKey, and ScienceDirect. The information available in these databases was reviewed; third, a review of the articles was performed in line with the screening and elimination of duplicates phase, according to the Prisma9 guideline; fourth, having the number of articles without duplicates, a review of the titles and a summary of said articles was made; fifth, of the articles that met selection criteria and allowed the research question to be answered, those were selected to carry out the analysis of the full-text content; and finally, in a blind manner, after solving the disagreements by consensus during this identification phase, the same authors conducted the review and full-text analysis, independently, of the content of the articles that met the mentioned criteria. From there, the evidence was extracted to be able to identify the main differences in the detection of RP between NC and IRT.

In the same way, in addition to what was published in the aforementioned databases, a search was included in the "grey literature" that corresponds to experiences published in journals not included in the Index Medicus or other databases (thesis, abstracts from conferences, pharmaceutical industry reports, etc.).

All relevant data referring to the assessment with NC (videocapillaroscopic or microscopic) and protocols used before its performance, concomitant pharmacological intervention (if any, for example, vasodilators), the diagnostic comparator (IRT, type of device, technique aspects, use of mobile phones, type of radiation, etc.), and the context in which the two diagnostic tests have been used (early diagnosis, late follow-up, test in response to treatment, etc.). Likewise, the outcome measures in their maximum number, according to the different possible microvascular findings, primarily in data searching on the similarities and differences within the two techniques, were evaluated. Data related to the safety of diagnostic techniques, in case of being informed, were also extracted.

Information processingAll the studies obtained through the search were synchronized with the Rayyan®10 web and mobile application program, validated for systematic searches. A spreadsheet in Excel format was designed with information on the primary (full-text review) and final articles (review of final articles) in separate sheets. During the selection phase, the Mendeley Desktop v1.19.2 software was used to evaluate full-text PDF articles, considering compliance with the eligibility criteria.

The variables that were analyzed were: country, year of publication, authors, journal, main and secondary study results, methodological evaluation, type of epidemiological design, estimates, main results, and conclusions.

The search strategy has been registered in the Mendeley Data repository (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/5w9fbp3wyj/1 DOI: 10.17632/5w9fbp3wyj.1).

Error and bias controlBeing a secondary source investigation, results were subject to the quality of the information of the published articles; however, for the final review, compliance with criteria was considered according to the type of epidemiological design, compliance to objectives, information analysis, and the authors` research articles conclusions.

A review of the articles was done in duplicate, with two different researchers, who finally reviewed compliance with criteria to identify the level of evidence of the selected articles. Publication, selection, and observer biases were all considered.

Data analysis and presentation techniquesFor the analysis and presentation of results, the role of the reviewers was to try to explain the possible causes of results variations of the primary articles, since these may be due to chance, study design, sample size, or how the exposure (or intervention) and outcomes were measured.

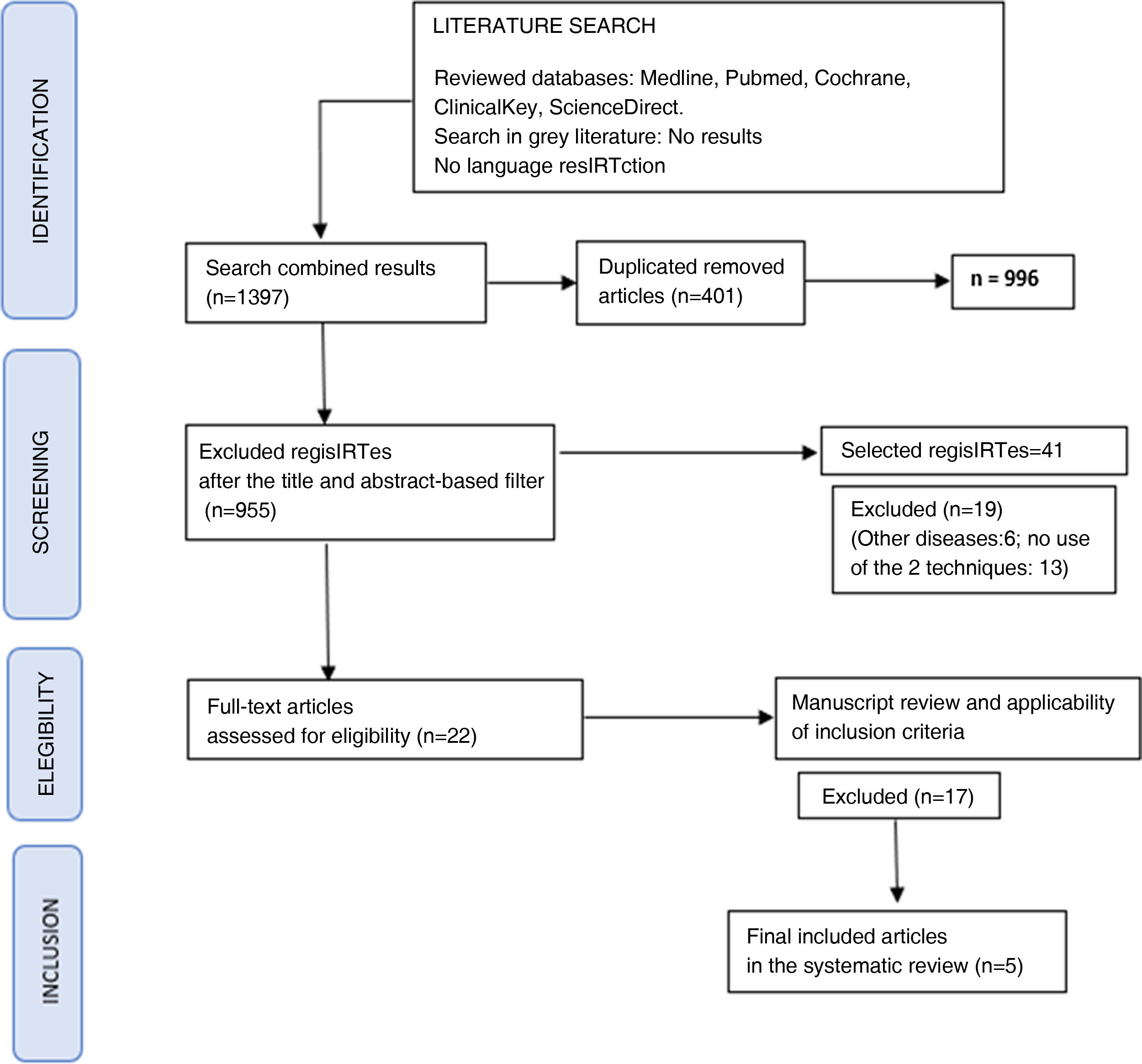

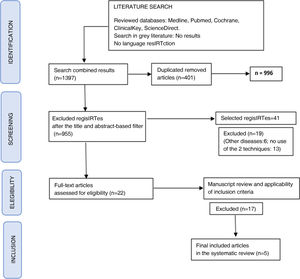

Regarding the presentation of results, all the steps of the review development process were detailed in a clear and organized way. A flowchart (Prisma flowchart) was prepared, which represents the article selection process, specifying the initial number of potentially eligible articles according to the performed search, up to those finally included, specifying the reasons why papers that were not finally considered were excluded. Similarly, the graphical representation of the results of the included studies was performed.

A narrative extraction was carried out on the tools used to measure outcomes, including quantitative data referring to effect measures, such as means, standard deviations, medians, and p values (in the case of being informed by the source articles, although these cannot be statistically grouped). A comprehensive search of the source articles was carried out on the concordance value of the microvascular findings between the two tests, if any (to estimate the common effect), and the statistical tools to calculate it. Studies were grouped according to their design. A synthesis without meta-analysis was proposed as a qualitative data analysis and not a quantitative analysis, given the heterogeneity of the articles, following the suggested SWIM11 guideline. For this purpose, the outcomes related to the type of classification of the microvascular findings were assessed (in all the articles that reported them), according to the two techniques, being the type of capillaroscopic pattern12 (according to the EULAR Study Group on Microcirculation in Rheumatic Diseases and the Scleroderma Clinical IRTals Consortium Group on Capillaroscopy, or others if described) and thermal pattern findings detailed in IRT. Consequently, and following the Prisma9 guideline, the variables to be evaluated were, for NC: category 1, non-scleroderma pattern (normal or non-specific abnormalities), and category 2, early, active, or late scleroderma pattern. For IRT: digital basal temperature, the temperature on the back, temperature gradient, and post-test cold test at different temperature levels.

Quality of evidenceThe two authors independently evaluated the level of evidence of the selected studies, applying the Joanna Briggs Institute level of evidence checklist.13

Additionally, the studies selected and considered for definitive inclusion were assessed for methodological quality before their inclusion in the review. Standardized tools for critical appraisal of the evidence from the JBI The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in Systematic Reviews Checklist were used, according to the different types of epidemiological designs of the articles that were included to assess the risk of bias.

Ethical considerationsFor the development of this systematic review, current national and international guidelines that seek to protect human participants in medical research and guarantee compliance with legal provisions14 were considered. Within national regulations, following Resolution 8430 of 1993, this systematic review is considered risk-free research.

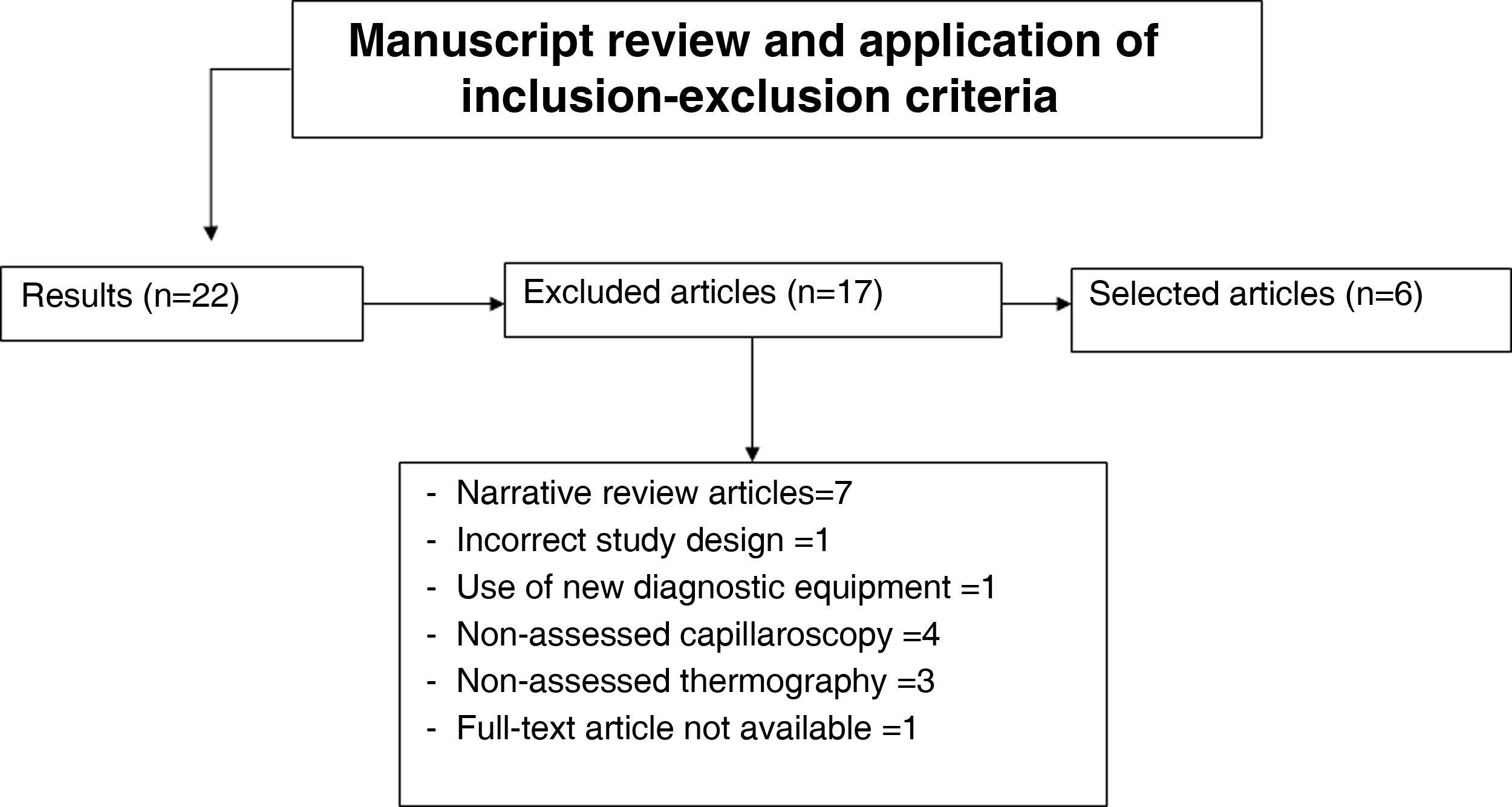

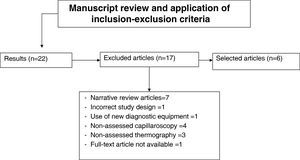

ResultsSearch resultsIn this systematic review, the number of articles found in the databases was 1397, of which 401 were discarded because they were duplicates. Two initial filters were carried out: the first by title and the second by the abstract content; consequently, 41 articles remained, of which 19 were excluded (another disease [n = 6]; no use of the two diagnostic tools [n = 13]). Due to their eligibility, 22 articles were selected for full-text reading. When reviewing these manuscripts and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 17 papers were rejected: seven narrative review articles, one incorrect study design, one used new diagnostic equipment [thermographic duosensor], four did not evaluate NC as a technique, three did not assess IRT as a technique, and one with no full-text availability for its revision.

All 22 articles were available in the databases in full text, except for one written in Polish; despite an extensive search on the internet, carried out both by the researchers and through bibliographic resource management centers of the institutions to which the authors are affiliated, not possible to obtain. An email was sent to the author, personally and directly, without obtaining a response. Finally, five articles15–19 were selected to be included in the systematic review (see Table 2 Description of the full-text articles and those included in the final review). Of these, three had a case-control and two had cross-sectional designs.

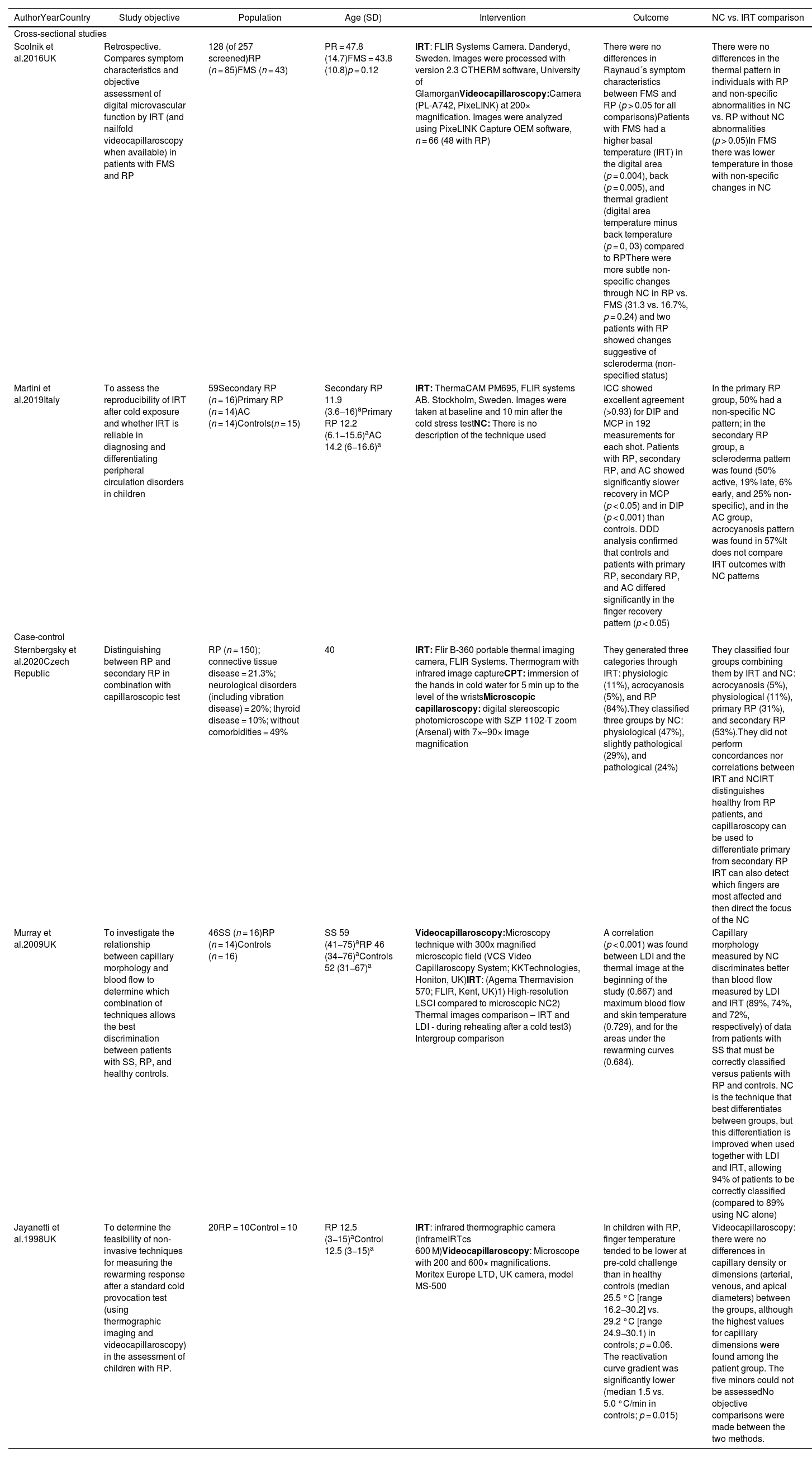

Characteristics of the studies included in this systematic review of the literature.

| AuthorYearCountry | Study objective | Population | Age (SD) | Intervention | Outcome | NC vs. IRT comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||

| Scolnik et al.2016UK | Retrospective. Compares symptom characteristics and objective assessment of digital microvascular function by IRT (and nailfold videocapillaroscopy when available) in patients with FMS and RP | 128 (of 257 screened)RP (n = 85)FMS (n = 43) | PR = 47.8 (14.7)FMS = 43.8 (10.8)p = 0.12 | IRT: FLIR Systems Camera. Danderyd, Sweden. Images were processed with version 2.3 CTHERM software, University of GlamorganVideocapillaroscopy:Camera (PL-A742, PixeLINK) at 200× magnification. Images were analyzed using PixeLINK Capture OEM software, n = 66 (48 with RP) | There were no differences in Raynaud´s symptom characteristics between FMS and RP (p > 0.05 for all comparisons)Patients with FMS had a higher basal temperature (IRT) in the digital area (p = 0.004), back (p = 0.005), and thermal gradient (digital area temperature minus back temperature (p = 0, 03) compared to RPThere were more subtle non-specific changes through NC in RP vs. FMS (31.3 vs. 16.7%, p = 0.24) and two patients with RP showed changes suggestive of scleroderma (non-specified status) | There were no differences in the thermal pattern in individuals with RP and non-specific abnormalities in NC vs. RP without NC abnormalities (p > 0.05)In FMS there was lower temperature in those with non-specific changes in NC |

| Martini et al.2019Italy | To assess the reproducibility of IRT after cold exposure and whether IRT is reliable in diagnosing and differentiating peripheral circulation disorders in children | 59Secondary RP (n = 16)Primary RP (n = 14)AC (n = 14)Controls(n = 15) | Secondary RP 11.9 (3.6−16)aPrimary RP 12.2 (6.1−15.6)aAC 14.2 (6−16.6)a | IRT: ThermaCAM PM695, FLIR systems AB. Stockholm, Sweden. Images were taken at baseline and 10 min after the cold stress testNC: There is no description of the technique used | ICC showed excellent agreement (>0.93) for DIP and MCP in 192 measurements for each shot. Patients with RP, secondary RP, and AC showed significantly slower recovery in MCP (p < 0.05) and in DIP (p < 0.001) than controls. DDD analysis confirmed that controls and patients with primary RP, secondary RP, and AC differed significantly in the finger recovery pattern (p < 0.05) | In the primary RP group, 50% had a non-specific NC pattern; in the secondary RP group, a scleroderma pattern was found (50% active, 19% late, 6% early, and 25% non-specific), and in the AC group, acrocyanosis pattern was found in 57%It does not compare IRT outcomes with NC patterns |

| Case-control | ||||||

| Sternbergsky et al.2020Czech Republic | Distinguishing between RP and secondary RP in combination with capillaroscopic test | RP (n = 150); connective tissue disease = 21.3%; neurological disorders (including vibration disease) = 20%; thyroid disease = 10%; without comorbidities = 49% | 40 | IRT: Flir B-360 portable thermal imaging camera, FLIR Systems. Thermogram with infrared image captureCPT: immersion of the hands in cold water for 5 min up to the level of the wristsMicroscopic capillaroscopy: digital stereoscopic photomicroscope with SZP 1102-T zoom (Arsenal) with 7×–90× image magnification | They generated three categories through IRT: physiologic (11%), acrocyanosis (5%), and RP (84%).They classified three groups by NC: physiological (47%), slightly pathological (29%), and pathological (24%) | They classified four groups combining them by IRT and NC: acrocyanosis (5%), physiological (11%), primary RP (31%), and secondary RP (53%).They did not perform concordances nor correlations between IRT and NCIRT distinguishes healthy from RP patients, and capillaroscopy can be used to differentiate primary from secondary RP IRT can also detect which fingers are most affected and then direct the focus of the NC |

| Murray et al.2009UK | To investigate the relationship between capillary morphology and blood flow to determine which combination of techniques allows the best discrimination between patients with SS, RP, and healthy controls. | 46SS (n = 16)RP (n = 14)Controls (n = 16) | SS 59 (41−75)aRP 46 (34−76)aControls 52 (31−67)a | Videocapillaroscopy:Microscopy technique with 300x magnified microscopic field (VCS Video Capillaroscopy System; KKTechnologies, Honiton, UK)IRT: (Agema Thermavision 570; FLIR, Kent, UK)1) High-resolution LSCI compared to microscopic NC2) Thermal images comparison – IRT and LDI - during reheating after a cold test3) Intergroup comparison | A correlation (p < 0.001) was found between LDI and the thermal image at the beginning of the study (0.667) and maximum blood flow and skin temperature (0.729), and for the areas under the rewarming curves (0.684). | Capillary morphology measured by NC discriminates better than blood flow measured by LDI and IRT (89%, 74%, and 72%, respectively) of data from patients with SS that must be correctly classified versus patients with RP and controls. NC is the technique that best differentiates between groups, but this differentiation is improved when used together with LDI and IRT, allowing 94% of patients to be correctly classified (compared to 89% using NC alone) |

| Jayanetti et al.1998UK | To determine the feasibility of non-invasive techniques for measuring the rewarming response after a standard cold provocation test (using thermographic imaging and videocapillaroscopy) in the assessment of children with RP. | 20RP = 10Control = 10 | RP 12.5 (3−15)aControl 12.5 (3−15)a | IRT: infrared thermographic camera (inframeIRTcs 600 M)Videocapillaroscopy: Microscope with 200 and 600× magnifications. Moritex Europe LTD, UK camera, model MS-500 | In children with RP, finger temperature tended to be lower at pre-cold challenge than in healthy controls (median 25.5 °C [range 16.2−30.2] vs. 29.2 °C [range 24.9−30.1) in controls; p = 0.06. The reactivation curve gradient was significantly lower (median 1.5 vs. 5.0 °C/min in controls; p = 0.015) | Videocapillaroscopy: there were no differences in capillary density or dimensions (arterial, venous, and apical diameters) between the groups, although the highest values for capillary dimensions were found among the patient group. The five minors could not be assessedNo objective comparisons were made between the two methods. |

AC: acrocyanosis; CPT: cold pressure test; DDD: distal-dorsal difference; SD: standard deviation; DIP: distal interphalangeal joints; SS: systemic sclerosis; FMS: fibromyalgia; RP: Raynaud's phenomenon; ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; LDI: laser Doppler imaging; LSCI: laser speckle contrast imaging; MCP: metacarpophalangeal joints; NC: capillaroscopy; p: p-value; UK: United Kingdom; IRT: infrared thermography.

The Prisma supplementary check table was prepared (see Annex 1 in additional material). A summary of the search process is presented below, using the Prisma diagram, according to systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines9 (see Figs. 1 and 2).

Evidence synthesisPopulationThe studies were carried out mainly in the Caucasian population (three in the United Kingdom17–19, one in Italy15, and another in the Czech Republic16). A total of 403 individuals were enrolled, of which 79 were minors. The mean age of all the studies comprises a wide range, since there are two studies with a pediaIRTc population (G. Martini – S. Jayanetti) with an approximate mean age of 12 years, while the other three articles16–18 included an adult population, with a mean age of 48 years. The predominant gender was females.

In the pediaIRTc population, there is no concordance in the results of the two analyzed papers. Martini et al.15 state that in NC there is a high possibility of poor image quality, due to several factors, such as the need to collaborate to keep the hand steady or damage of the periungual region by nail-biting, traumatism of fingers/nails, or infections. Another limitation is that the growing microvascular network gradually changes to a mature adult form, thus non-specific microvascular abnormalities such as capillary tortuosity may be evidenced. Jayanetti et al.19 mentioned that the measurement of capillary dimensions by videocapillaroscopy is feasible in children, although only in those over five years. Despite this, in the study by Jayanetti et al., children were not matched by sex and age (it is known, in adults, that cutaneous blood flow of the hands is greater in men than in women). Additionally, none of the children studied had a definite RP, and the question of whether the rewarming pattern differs between children with primary and secondary RP could not be solved.

EquipmentOf the five articles included,15–19 two included videocapillaroscopy,18,19 two conventional or microscopic NC16,17 and one did not describe well the NC technique used.15 The equipment used for NC had different models with variations in zoom range and image magnification; however, despite these differences, two authors agree in categorizing NC (conventional or videocapillaroscopy) as the method that best helps to differentiate primary from secondary RP.16,17

For IRT, one of the articles used a FLIR B-360 Systems16 portable thermal imaging camera and in the other studies, FLIR Systems cameras and 600 M infrared cameras.

DiseasesMost of the studies include RP, but three articles included fibromyalgia (FMS)-associated RP,18 systemic sclerosis (SS),17 and acrocyanosis.15 Only one of the articles (Scolnik et al.18) is not conclusive in its final results and recommends additional prospective studies to verify their findings. The authors mention that they do not support an association between FMS and digital microvascular dysfunction and suggest that RP symptoms in FMS may be caused by different mechanisms than those observed in primary RP or secondary to autoimmune diseases.18

Primary and secondary Raynaud's phenomenonOnly two of the articles16,17 use both techniques (IRT and NC) to differentiate primary from secondary FR from RS. In these two articles, conventional or microscopic NC is used as a diagnostic technique.

Sternbersky et al.16 maintain that NC is the ideal diagnostic method to distinguish primary from secondary RP. Instead, IRT is the technique that best differentiates healthy patients from those with RP. Murray et al.17 reports that NC is the technique that best discriminates SS, RP, and healthy controls. However, if the goal is to differentiate between healthy controls and secondary RP subjects, rather than detect underlying connective tissue disease, then IRT is the method of choice.

DifferencesIt is not possible to establish differences since both techniques are different and assessed completely heterogeneous populations. In the case of the two studies conducted in pediaIRTc population,15,19 non-concordant results were found, and although it seems that the studies in the adult population16–18 presented similar results (microscopic NC as the diagnostic technique that best discriminates primary from secondary RP), the secondary RP-associated connective tissue diseases are completely different. A common effect measure could not be calculated as no statistical analyzes were performed comparing the two techniques in the primary articles, which could have led to a common estimated analysis.

Advantages and disadvantagesThe use of IRT over NC is seen as a possible advantage in the pediaIRTc population, due to technical ease at the time of its performance, since the periungual region may be damaged in children due to nail/finger trauma (eg, nail-biting) or associated infections.15 In the other studies, it was not possible to distinguish other types of advantages or disadvantages of one technique over the other.

SecurityNone of the articles described complications or side effects after performing the diagnostic techniques studied. This narrative description of the evidence synthesis was reviewed and grouped according to the SWIM guideline (see Annex 2 for additional material).

Quality of evidenceIn this systematic review of the literature, the level of evidence was as expected, with the prior knowledge of the absence of research or randomized controlled clinical IRTals in current literature.

The level of evidence of the five articles15–19 was 3b, following the Joanna Briggs list (see Annex 3 in additional material). According to the analysis of quality and level of evidence, the three reviewed articles complied with more than 50% of the items (risk of bias close to 50%).

DiscussionIn the present systematic review of the literature, to the knowledge of the authors, the microvascular findings of these two diagnostic tools, NC (microscopic or videocapillaroscopy) and IRT, when used concomitantly in RP, were assessed for the first time. Although this disease is not very prevalent, the complications that occur in secondary RP are very serious and disabling, and the quantification of the microvascular alterations that occur in patients with RP secondary to connective tissue disease is notoriously difficult, which makes it necessary to improve the timely diagnostic process.

Objective measures are needed to help distinguish primary from secondary RP, determine its nature, and performing careful monitoring in those with secondary disease to determine its association with other disorders.1

According to the latest expert consensus on NC and image analysis conducted in 2020,12 NC is a non-invasive and safe tool for evaluating microcirculation morphology, increasingly used by international clinicians, both in daily practice and in the research context, to differentiate primary from secondary RP, predicting disease progression, and monitoring treatment effects.

The gold standard for the evaluation of RP is high magnification videocapillaroscopy. The capillaroscopic pattern for the development of connective tissue disease has a high predictive value (47%)20; nailfold NC is indicated in all patients with Raynaud's symptoms.

In their review article, Herrick and Murray6 point out that NC is the method that best helps to differentiate primary from secondary RP, referring to microvascular findings in the nailfold as normal in primary RP, but abnormal in most patients with secondary RP. Such results are shared in the same way by Lambova in his review article in 2016.20 However, some authors consider that videocapillaroscopes are relatively expensive and require special training.21 Nonetheless, this has been refuted by more recent studies, such as the capillaroscopy study group of the Pan American League of Rheumatology (PANLAR),22 which found that there is moderate agreement among rheumatologists for the identification of SS videocapillaroscopy patterns and substantial agreement, regardless of previous experience in identifying normal and abnormal images. The agreement for active and late pattern identification is higher than for early pattern.

Some researchers suggest that for those who do not have access to this resource, a low magnification dermatoscope or USB microscope (conventional–microscopic) can be used, in which the capillaries are directly visualized through an optical magnification system of approximately 10−100×, mainly in the finger nailfold.23

On the other hand, IRT measures surface temperature, an indirect measure that assesses digital vascular function. Until now, it is a technique with which few rheumatologists are familiar; its use has been limited mainly to specialized centers and research.

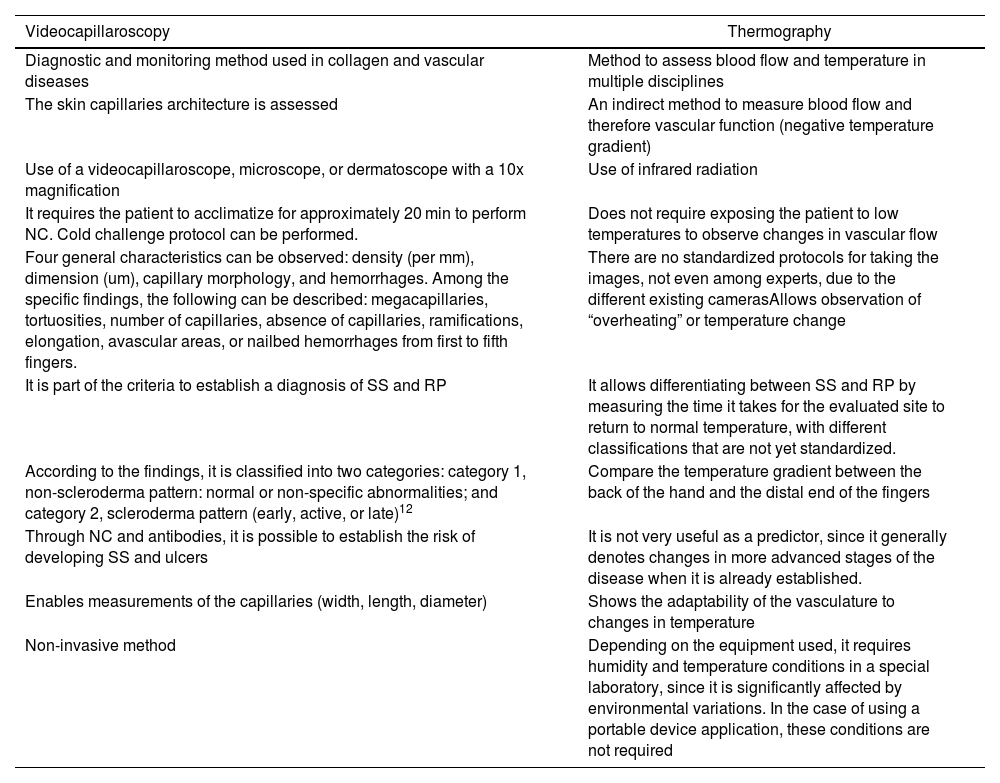

Recently, the performance of low-cost thermography was tested through portable cameras connected to mobile devices,24 and it stands out that it is a novel and portable tool, but with a lower sensitivity than the wide-field microscope, which works acceptably, even in inexperienced hands. However, there are no studies that show that it can replace NC. Table 3 depicts some characteristics of the NC and IRT.

Characteristics of videocapillaroscopy and thermography.

| Videocapillaroscopy | Thermography |

|---|---|

| Diagnostic and monitoring method used in collagen and vascular diseases | Method to assess blood flow and temperature in multiple disciplines |

| The skin capillaries architecture is assessed | An indirect method to measure blood flow and therefore vascular function (negative temperature gradient) |

| Use of a videocapillaroscope, microscope, or dermatoscope with a 10x magnification | Use of infrared radiation |

| It requires the patient to acclimatize for approximately 20 min to perform NC. Cold challenge protocol can be performed. | Does not require exposing the patient to low temperatures to observe changes in vascular flow |

| Four general characteristics can be observed: density (per mm), dimension (um), capillary morphology, and hemorrhages. Among the specific findings, the following can be described: megacapillaries, tortuosities, number of capillaries, absence of capillaries, ramifications, elongation, avascular areas, or nailbed hemorrhages from first to fifth fingers. | There are no standardized protocols for taking the images, not even among experts, due to the different existing camerasAllows observation of “overheating” or temperature change |

| It is part of the criteria to establish a diagnosis of SS and RP | It allows differentiating between SS and RP by measuring the time it takes for the evaluated site to return to normal temperature, with different classifications that are not yet standardized. |

| According to the findings, it is classified into two categories: category 1, non-scleroderma pattern: normal or non-specific abnormalities; and category 2, scleroderma pattern (early, active, or late)12 | Compare the temperature gradient between the back of the hand and the distal end of the fingers |

| Through NC and antibodies, it is possible to establish the risk of developing SS and ulcers | It is not very useful as a predictor, since it generally denotes changes in more advanced stages of the disease when it is already established. |

| Enables measurements of the capillaries (width, length, diameter) | Shows the adaptability of the vasculature to changes in temperature |

| Non-invasive method | Depending on the equipment used, it requires humidity and temperature conditions in a special laboratory, since it is significantly affected by environmental variations. In the case of using a portable device application, these conditions are not required |

SS: systemic sclerosis; NC: capillaroscopy; RP: Raynaud phenomenon.

An interesting group in which IRT represents a promising and reliable instrument to diagnose and monitor peripheral circulation disorders could be the pediaIRTc population; in this group, IRT is a trustworthy and reproducible method, which could be used to avoid complications when other diagnostic tools are employed. In the present review, one of the studies15, demonstrates this, and mentions IRT as a diagnostic method capable of evaluating thermal images to distinguish primary from secondary RP and acrocyanosis, based on the analysis of the rewarming pattern of acrocyanosis in children; however, the authors15 highlight different sources of poor quality.

On the other hand, some experts differ from the previous concept, such as Jayanetti et al.19, authors of one of the studies included in this review, who disagree with the use of IRT as a tool for assessing childhood RP. Their study19 was the first to conduct a detailed evaluation of capillary dimensions in children using videocapillaroscopy and demonstrated that cold challenge testing and measurement of capillary dimensions are feasible in children with RP, as well as that these children have abnormal overheating.

Finally, these two techniques (IRT and NC) may play a role in the diagnosis and evaluation of childhood RP, and although the findings are not similar in the two studies, they do provide some recommendations for further studies in this population.

In this review, additional studies16–18 conducted in the adult population were analyzed, which offer some similar results to each other.

Sternbersky et al.16 demonstrated that the combined results of IRT and microscopic NC determined the final diagnosis (Table 1). IRT distinguishes healthy patients from those with RP, and microscopic NC can be used to differentiate primary from secondary RP. IRT can also detect which fingers are most affected and can direct the focus of the NC. It could be concluded from this study that, being non-invasive, the IRT examination is a safe method for patients, including a cold-pressure test (CPT). However, the use of a CPT is contraindicated for patients with critical digital ischemia, where it could cause significant progression. Unfortunately, the authors did not perform an assessment of concordance between the two diagnostic tests to conclude comparing the two techniques, and additionally, more studies would be required to demonstrate the diagnostic performance using the two techniques. Murray et al.17 used microscopic laser Doppler, IRT, and NC imaging to measure cutaneous blood vessel function and nailfold capillary morphology. The key finding of this study was that capillary morphology as measured by NC discriminates better than blood flow (as measured by laser Doppler and IRT between patients with SS, RP, and controls. However, classification is further improved if all three techniques are combined, allowing 94% of patients (compared to 89% using NC alone) to be correctly classified. Scolnik et al.18 compared symptom characteristics and objective assessment of digital microvascular function using IRT (and nailfold videocapillaroscopy when available) in patients with FMS (reporting Raynaud symptoms) and primary RP. There were no differences in the thermal pattern in individuals with RP and non-specific NC abnormalities when compared with RP patients without NC abnormalities. Additional prospective studies are required to verify these findings.

Although it is true that in this systematic review of the literature few studies were found that compared NC with IRT, it is worth mentioning that the latter has been compared with other techniques. In this regard, Wilkinson et al.24 compared IRT with speckle contrast laser for primary RP and found that both demonstrated good potential as outcome measures; laser speckle contrast, standard IRT, and mobile thermography had very high convergent validity.

This study has the following weaknesses: the search strategy protocol was not registered in the Prospero repository, although it was registered in the Mendeley Repository Data, following the Prospero guidelines. Likewise, the characteristics of the different populations studied are heterogeneous (two studies in the pediaIRTc population, and three studies in adults), with no possibility of matching, either by sex or age.

There is wide variability in secondary RP-associated disorders (FMS, acrocyanosis, SS), with different objectives in each of the studies15,17,18; in one of the papers, the capillaroscopic technique used was unclear.15

The variables and outcomes to be analyzed did not use a common effect measure across the studies; therefore, they prevented its estimate in all papers.

ConclusionsAccording to the findings of this systematic review of the literature, it is not possible to compare the results of NC against IRT or to conclude that there are clear differences or advantages/disadvantages in the preferential use of one of the two diagnostic techniques in RP; however, there are promising findings in each of them. The NC has had a good development when compared with IRT for the differentiation between primary and secondary RP, evidenced in two of the reviewed articles16,17; in addition, it allows monitoring of patients and their evolution or response to medical treatment. Its usefulness has been widely demonstrated and its results are solid within the SS diagnostic algorithm in research that does not use IRT as a comparative diagnostic tool; in general, it has good reproducibility, regardless of previous experience in identifying normal and abnormal images. IRT is a diagnostic method that could allow the differentiation of healthy patients from those with primary and secondary RP, and it could be a method indicated in the pediaIRTc population due to the low risk of lesions secondary to videocapillaroscopy when CPT is used; however, the level of evidence of the study prevents drawing solid conclusions in this topic. Additional studies are required to determine the usefulness of the combination of the two techniques in the RP diagnostic algorithm.

This systematic review of the literature is intended to be a support tool for future researchers, encouraging the expansion of knowledge in these areas, especially considering the technological advances in NC and IRT that open up great possibilities for the timely diagnosis of RP.

FinancingThis study did not require financial resources provided by the entities to which the authors belong; it was approved by the corresponding research committees.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the topic and the results of this study.