Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune inflammatory disease that presents great clinical heterogeneity, so that up to 60% of patients may develop lupus nephropathy (LN).

ObjectiveTo identify demographic, clinical, and biochemical characteristics of patients presenting with and without lupus nephritis at the time of SLE diagnosis in a cohort of Mexican patients

Materials and methodsThis is a cross-sectional, analytical, and single-centre study. Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables and the comparison was made with Pearson's Chi2 statistical test or Fisher's exact test. For the quantitative variables, their distribution was calculated and according to this, Student's t was used in case of normal distribution and Mann-Whitney U for those with free distribution.

ResultsOf 160 patients, 79 (49.37%) had LN. These individuals had a higher prevalence of serositis (14.3 vs. 8.1%, p = 0.048) and arterial hypertension (40.50% vs. 24.6%, p = 0.033), while those without LN had a higher prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis and joint disease (6 vs. 1%, p = 0.052), allergies (43.2 vs. 20.25%, p = 0.002), infections (23.45 vs. 10%, p = 0.020), and lower levels of C3 (52.25±28.7 vs. 74.6±32.2 mg/dl, p < 0.001).

ConclusionsThe characteristics described in our cohort are like those presented in other Latino and Asian series. However, the presence of concomitant infections at the time of SLE diagnosis has not been described and should be considered for future research.

El lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) es una enfermedad inflamatoria autoinmune que presenta una gran heterogeneidad clínica, por lo que hasta el 60% de los pacientes pueden desarrollar nefropatía lúpica (NL).

ObjetivoIdentificar las características demográficas, clínicas y bioquímicas de los pacientes que presentan NL y los que no la presentan en el momento del diagnóstico de LES en una cohorte de pacientes mexicanos.

Materiales y métodosEstudio transversal, analítico y de un solo centro. Se realizaron pruebas de normalidad y se aplicó t de Student o U de Mann Withney dependiendo del tipo de variable. Para determinar la diferencia entre las varibales se realizó prueba de chi-cuadrado o prueba exacta de Fisher.

ResultadosDe 160 pacientes, 79 (49,37%) presentaron NL, estos tuvieron una mayor prevalencia de serositis (14,3 vs. 8,1%, p = 0,048) e hipertensión arterial (40,50% vs. 24,6%, p = 0,033) y aquellos sin NL una mayor prevalencia de artritis reumatoide y afección articular (6 vs. 1%, p = 0.052), alergias (43,2 vs. 20,25%, p = 0,002), infecciones (23,45 vs. 10%, p = 0,020) y niveles más bajos de C3 (52,25±28,7 vs. 74,6±32,2 mg/dl, p < 0,001).

ConclusionesLas características descritas en nuestra cohorte son similares a las presentadas en otras series latinas y asiaticas. Sin embargo, la presencia de infecciones concomitantes al momento del diagnóstico de LES no había sido descrita y debe ser considerada para el futuro de nuevas investigaciones.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic and heterogeneous autoimmune inflammatory disease that can affect any part of the body. Most of its pathology is related to deposits of immune complexes in various organs, which activate the complement system and other mediators of inflammation. The symptoms vary from person to person, may appear and disappear, depending on the part of the body affected, and are classified as mild, moderate, or severe. Registry-derived studies have usually a large number of patients from non-experimental clinical settings and allow for more extensive follow-up than the one that can be achieved in clinical trials.1

Lupus nephropathy (LN) is one of the most serious complications of SLE, which can cause irreversible kidney damage if is not timely identified or treated appropriately. It is defined as an inflammatory kidney disease secondary to SLE activity, which occurs as a result of an abnormal immune response in which autoantibodies and immune complexes directly damage the glomerular structure and function.2 This nosology has a variable clinical presentation and can range from subnephrotic proteinuria or microhematuria to an evident picture of acute kidney injury. LN is present at the time of the diagnosis of SLE in 40–70%, with an exact incidence that depends on factors such as race, age, and gender.3 Up to 60–80% of patients diagnosed with SLE will develop urinary or renal function disorders at some point during the course of the disease.4 In general terms, it affects black, Asian and Latino individuals more, with a female-male ratio of 9:1.5,6

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines determine the presence of specific biochemical manifestations or histopathological findings in patients with SLE as essential for the definition of LN, which are classified into different categories associated with a prognosis and a particular therapeutic approach.7 When the clinical results are mild hematuria and proteinuria, the renal lesions are usually mesangial (classes I or II); if it manifests as nephritic syndrome or has a rapidly progressive behavior, there are usually active glomerular lesions (classes III and IV); when it presents as a pure nephrotic syndrome, it is frequent to find glomerular damage of membranous type (class V), and when there is chronic kidney disease, it is expected to find advanced sclerosing alterations (class VI).8,9 However, the clinical and histopathological presentation is very heterogeneous and clinical and laboratory findings prevent predicting with certainty the type and degree of the lesions.

Despite the advances in diagnosis and treatment, LN continues to be a complex and heterogeneous pathology, whose prognosis and evolution can vary widely from one patient to another,10 therefore, the objective of this study is to compare the demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics of those who debuted with LN, in contrast to those who did not present it at the time of diagnosis, in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of the profiles associated with this renal complication in the context of SLE in the Mexican population.

Materials and methodsThis is an analytical cross-sectional study that included 160 patients diagnosed with SLE, belonging to the LUPUS-IMMex cohort of the Hospital de Especialidades del Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI. The demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics of the subjects who presented LN at the time of the diagnosis of SLE were compared with those of the patients who did not present it. The cohort included patients with a diagnosis of SLE since the year 2009, who met classification criteria either from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1997, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) 2012, or the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)/ACR 2019. LN was defined as the presence of 24 -h proteinuria higher than 500 mg/day or microhematuria or deterioration of renal function, or those who had a renal biopsy compatible with LN at the time of the diagnosis of SLE. Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables and the comparison was made with Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s f statistical tests. The distribution of the quantitative variables was calculated and, according to this, Student's t test was used in the case of normal distribution and Mann-Whitney U test for those with free distribution. Any p-value < 0.05 is considered significant. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 was used.

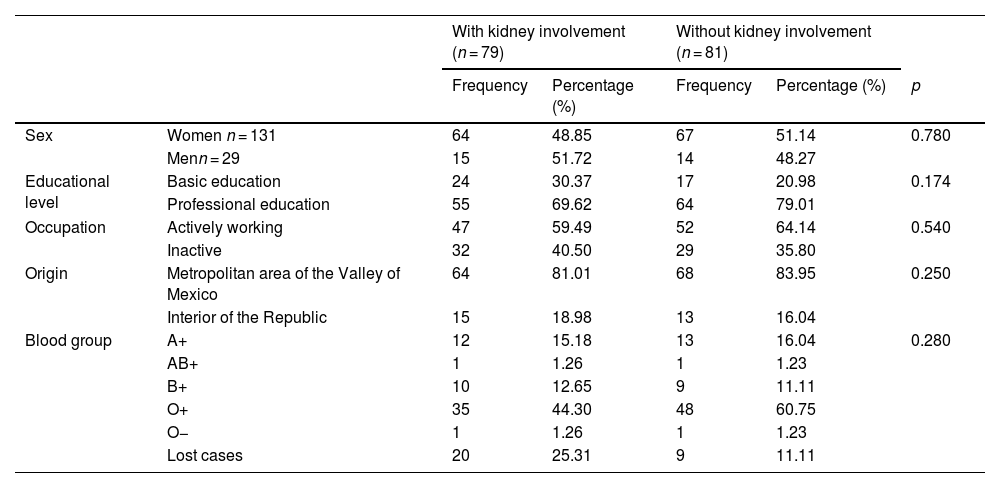

ResultsOf the 160 patients diagnosed with SLE, 79 (49.37%) had LN at the time of diagnosis. There was no significant difference in sociodemographic variables between those who debuted with LN and those who did not (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics.

| With kidney involvement (n = 79) | Without kidney involvement (n = 81) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | p | ||

| Sex | Women n = 131 | 64 | 48.85 | 67 | 51.14 | 0.780 |

| Menn = 29 | 15 | 51.72 | 14 | 48.27 | ||

| Educational level | Basic education | 24 | 30.37 | 17 | 20.98 | 0.174 |

| Professional education | 55 | 69.62 | 64 | 79.01 | ||

| Occupation | Actively working | 47 | 59.49 | 52 | 64.14 | 0.540 |

| Inactive | 32 | 40.50 | 29 | 35.80 | ||

| Origin | Metropolitan area of the Valley of Mexico | 64 | 81.01 | 68 | 83.95 | 0.250 |

| Interior of the Republic | 15 | 18.98 | 13 | 16.04 | ||

| Blood group | A+ | 12 | 15.18 | 13 | 16.04 | 0.280 |

| AB+ | 1 | 1.26 | 1 | 1.23 | ||

| B+ | 10 | 12.65 | 9 | 11.11 | ||

| O+ | 35 | 44.30 | 48 | 60.75 | ||

| O− | 1 | 1.26 | 1 | 1.23 | ||

| Lost cases | 20 | 25.31 | 9 | 11.11 | ||

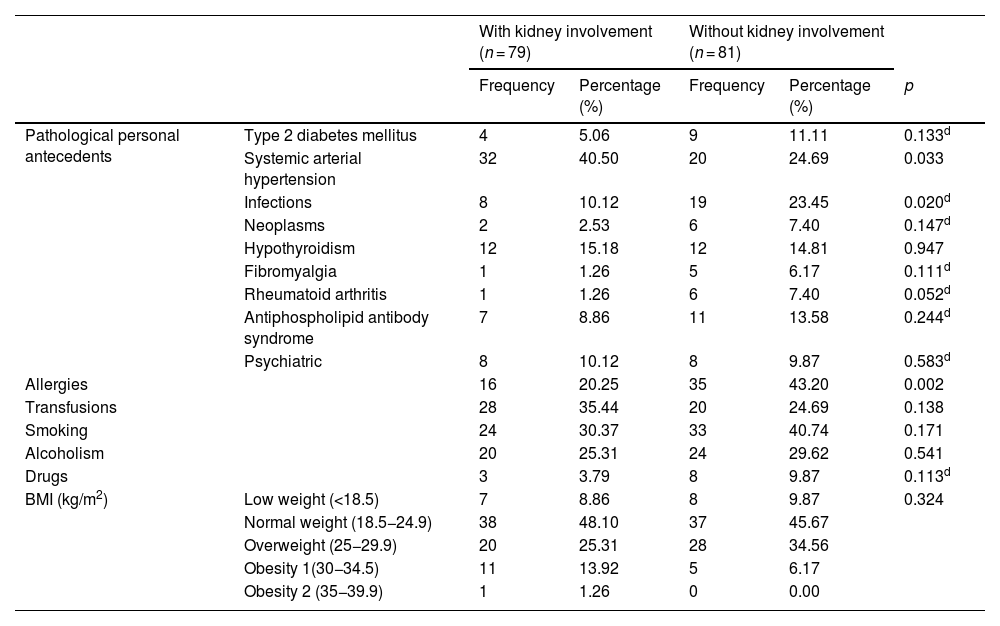

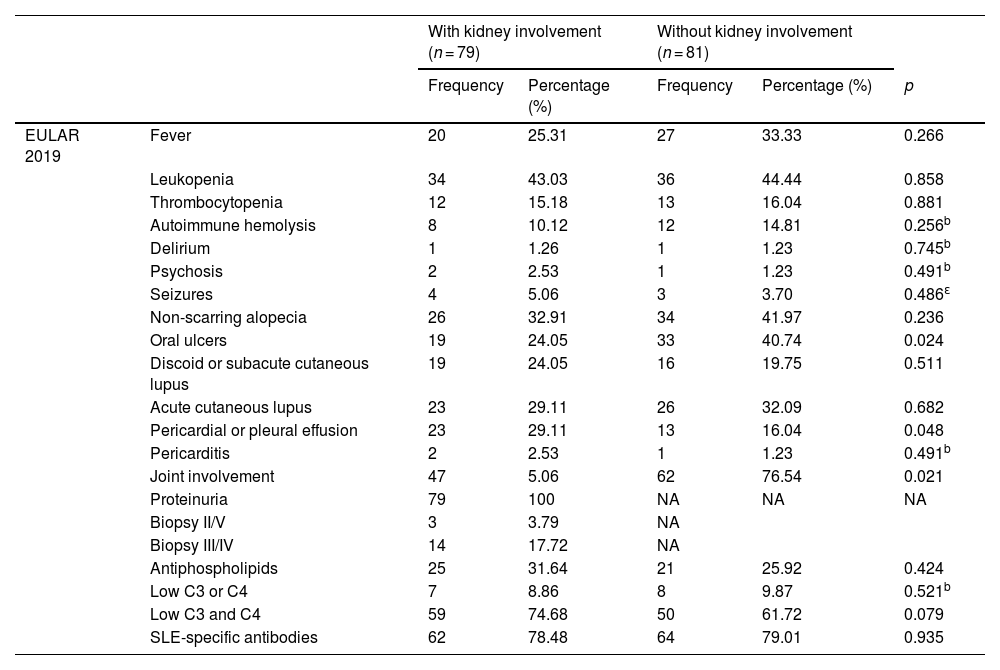

As can be seen in Table 2, systemic arterial hypertension, defined as blood pressure levels higher than 130/80 mmHg, was more frequent in the patients with LN (40.50%, p = 0.033). The presence of infectious processes (23.45%), allergies (43.20%), rheumatoid arthritis (7.40%) (p = 0.020, p = 0.002 and p = 0.052, respectively) and oral ulcers (p = 0.024) is more frequent in patients without LN (Table 3). Pericardial or pleural effusion (p = 0.048) was more common in patients with LN, as well as the decrease in complement fractions 3 and 4 (p < 0.079). Those with LN, unlike patients without LN, had higher levels of total cholesterol (199.00 mg/dL [165.70–248.70 mg/dL] vs. 142.00 mg/dL [127.00–172.60 mg/dL], p < 0.001), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) (119.66±63.26 mg/dL vs. 82.38±39.65 mg/dL, p = 0.037) and triglycerides (244.97±105.37 mg/dL vs. 168.90±101.84 mg/dL, p = 0.009) (Table 4).

Antecedents and clinical characteristics.

| With kidney involvement (n = 79) | Without kidney involvement (n = 81) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | p | ||

| Pathological personal antecedents | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 4 | 5.06 | 9 | 11.11 | 0.133d |

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 32 | 40.50 | 20 | 24.69 | 0.033 | |

| Infections | 8 | 10.12 | 19 | 23.45 | 0.020d | |

| Neoplasms | 2 | 2.53 | 6 | 7.40 | 0.147d | |

| Hypothyroidism | 12 | 15.18 | 12 | 14.81 | 0.947 | |

| Fibromyalgia | 1 | 1.26 | 5 | 6.17 | 0.111d | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 | 1.26 | 6 | 7.40 | 0.052d | |

| Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome | 7 | 8.86 | 11 | 13.58 | 0.244d | |

| Psychiatric | 8 | 10.12 | 8 | 9.87 | 0.583d | |

| Allergies | 16 | 20.25 | 35 | 43.20 | 0.002 | |

| Transfusions | 28 | 35.44 | 20 | 24.69 | 0.138 | |

| Smoking | 24 | 30.37 | 33 | 40.74 | 0.171 | |

| Alcoholism | 20 | 25.31 | 24 | 29.62 | 0.541 | |

| Drugs | 3 | 3.79 | 8 | 9.87 | 0.113d | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Low weight (<18.5) | 7 | 8.86 | 8 | 9.87 | 0.324 |

| Normal weight (18.5−24.9) | 38 | 48.10 | 37 | 45.67 | ||

| Overweight (25−29.9) | 20 | 25.31 | 28 | 34.56 | ||

| Obesity 1(30−34.5) | 11 | 13.92 | 5 | 6.17 | ||

| Obesity 2 (35−39.9) | 1 | 1.26 | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| With kidney involvement (n = 79) | Without kidney involvement (n = 81) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 27 (20−35) | 28 (23−38) | 0.249b | |||

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 24.75 (±4.70) | 24.00 (±3.87) | 0.282c | |||

BMI: body mass index; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; p: χ2.

Classification criteria for SLE.

| With kidney involvement (n = 79) | Without kidney involvement (n = 81) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | p | ||

| EULAR 2019 | Fever | 20 | 25.31 | 27 | 33.33 | 0.266 |

| Leukopenia | 34 | 43.03 | 36 | 44.44 | 0.858 | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 12 | 15.18 | 13 | 16.04 | 0.881 | |

| Autoimmune hemolysis | 8 | 10.12 | 12 | 14.81 | 0.256b | |

| Delirium | 1 | 1.26 | 1 | 1.23 | 0.745b | |

| Psychosis | 2 | 2.53 | 1 | 1.23 | 0.491b | |

| Seizures | 4 | 5.06 | 3 | 3.70 | 0.486ε | |

| Non-scarring alopecia | 26 | 32.91 | 34 | 41.97 | 0.236 | |

| Oral ulcers | 19 | 24.05 | 33 | 40.74 | 0.024 | |

| Discoid or subacute cutaneous lupus | 19 | 24.05 | 16 | 19.75 | 0.511 | |

| Acute cutaneous lupus | 23 | 29.11 | 26 | 32.09 | 0.682 | |

| Pericardial or pleural effusion | 23 | 29.11 | 13 | 16.04 | 0.048 | |

| Pericarditis | 2 | 2.53 | 1 | 1.23 | 0.491b | |

| Joint involvement | 47 | 5.06 | 62 | 76.54 | 0.021 | |

| Proteinuria | 79 | 100 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Biopsy II/V | 3 | 3.79 | NA | |||

| Biopsy III/IV | 14 | 17.72 | NA | |||

| Antiphospholipids | 25 | 31.64 | 21 | 25.92 | 0.424 | |

| Low C3 or C4 | 7 | 8.86 | 8 | 9.87 | 0.521b | |

| Low C3 and C4 | 59 | 74.68 | 50 | 61.72 | 0.079 | |

| SLE-specific antibodies | 62 | 78.48 | 64 | 79.01 | 0.935 | |

| With kidney involvement (n = 79) | Without kidney involvement (n = 81) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EULAR 2019 score | 24.22 (±7.22) | 19.42 (±5.04) | 0.013a | |||

Anti-DNA: anti-deoxyribonucleic antibodies; C3 and C4: complement proteins 3 and 4; EULAR: European League Against Rheumatism; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; p: χ2.

Interquartile range from 25 to 75 (IQR 25–75).

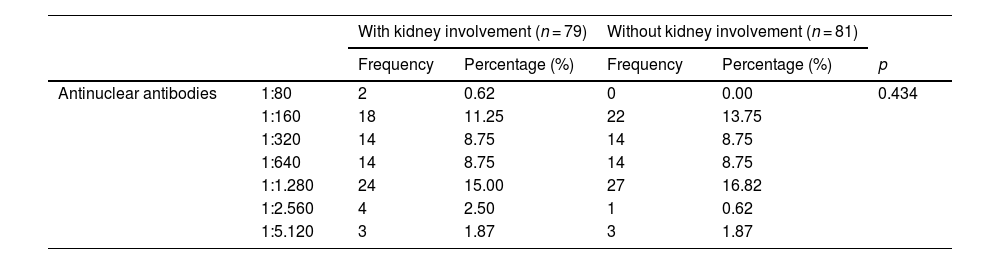

Biochemical characteristics.

| With kidney involvement (n = 79) | Without kidney involvement (n = 81) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | p | ||

| Antinuclear antibodies | 1:80 | 2 | 0.62 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.434 |

| 1:160 | 18 | 11.25 | 22 | 13.75 | ||

| 1:320 | 14 | 8.75 | 14 | 8.75 | ||

| 1:640 | 14 | 8.75 | 14 | 8.75 | ||

| 1:1.280 | 24 | 15.00 | 27 | 16.82 | ||

| 1:2.560 | 4 | 2.50 | 1 | 0.62 | ||

| 1:5.120 | 3 | 1.87 | 3 | 1.87 | ||

| With kidney involvement (n = 79) | Without kidney involvement (n = 81) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-DNA (IU/mL) | 265.00 (46.60−664.00) | 258.50 (80.32−624.75) | 0.912 c | |||

| C3 (mg/dL)a | 52.25 (±28.76) | 74.59 (±32.21) | 0.000 b | |||

| C4 (mg/dL) | 6.30 (2.90−10.57) | 8.30 (3.83−13.10) | 0.087 c | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL)a | 10.60 (±2.39) | 11.36 (±3.14) | 0.099 b | |||

| Leukocytes (cells/mm3)* | 5,768.99 (±331.25) | 5.908.31 (±602.26) | 0.804 b | |||

| Lymphocytes (cells/mm3)a | 1,214.80 (±100.10) | 1,227.85 (±130.47) | 0.937 b | |||

| Neutrophils (cells/mm3) | 3,600 (2,225−5,525) | 3,115 (2,080−5,225) | 0.748 c | |||

| Platelets (×103 cells/mm3)a | 229.88 (±109.68) | 221.92 (±111.08) | 0.066 b | |||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 89.00 (87.75−100.00) | 91,00 (82,50−102,50) | 0.541 c | |||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.03 (0.71−1.93) | 0.71 (0.63−0.86) | 0.000 c | |||

| Total proteins (g/dL)a | 5.49 (±1.14) | 6.84 (±1.13) | 0.000 b | |||

| Albumin(g/dL)a | 2.55 (±0.78) | 3.58 (±0.71) | 0.000 b | |||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 199.00 (165.75−248.75) | 142.00 (127.00−172.50) | 0.000 c | |||

| Cholesterol LDL (mg/dL)a | 119.66 (±63.26) | 82.38 (±39.65) | 0.037 b | |||

| Cholesterol HDL (mg/dL)a | 41.99 (±20.35) | 42.00 (±18.41) | 0.998 b | |||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL)a | 244.97 (±105.37) | 168.90 (±101.84) | 0.009 b | |||

| Lactic dehydrogenase (IU/L) | 332.00 (215.25−447.75) | 321.00 (243.25−445.00) | 0.763 c | |||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.30 (0.22−0.48) | 0.44 (0.30−0.88) | 0.003 c | |||

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.18 (0.12−0.28) | 0.22 (0.14−0.32) | 0.067 c | |||

| C-reactive protein (g/dL) | 1.03 (0.29−9.44) | 1.33 (0.34−12.20) | 0.393 c | |||

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/hour)a | 36.38 (±3.32) | 29.86 (±2.68) | 0.127 b | |||

| Proteinuria on general urine examination (mg/dL) | 500 (150−791) | 0 (0−100) | 0.000 c | |||

| Creatinine clearance in 24-h urine (ml/min/1.73 m2 BSA)a | 76.25 (±6.44) | 107.69 (±10.85) | 0.030b | |||

| Proteins in 24-h urine (mg/24 h) | 2,400 (900−5,250) | 193 (139−315) | 0.000c | |||

| CKD-EPI (mL/min) | 84.20 (39.00−117.50) | 106.25 (86.55−122.48) | 0.001 c | |||

Anti-DNA: anti-deoxyribonucleic antibodies; C3 and C4: complement proteins 3 and 4; CKD-EPI: Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; HDL: high-density lipoproteins; LDL: Low-density lipoproteins; IU: International Units; p: χ2.

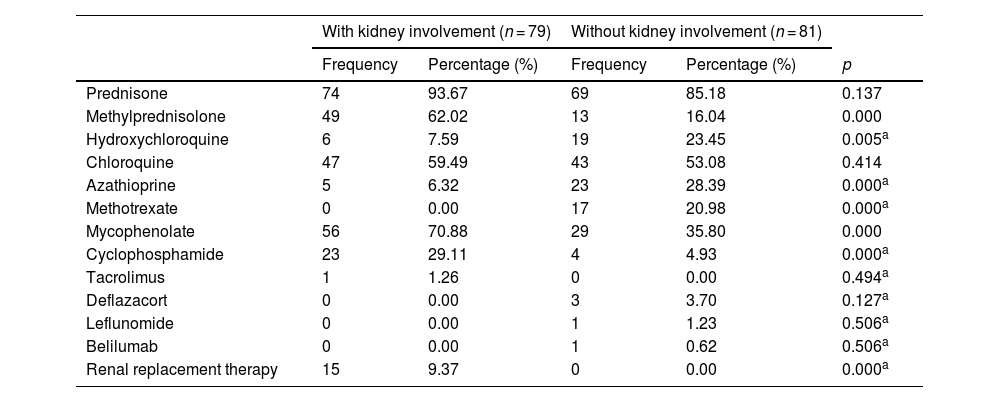

The most commonly used drugs for the treatment of LN were methylprednisolone (30.62%), mycophenolate mofetil (34.99%) and cyclophosphamide (14.37%) (p < 0.001); the most commonly used in patients without LN were hydroxychloroquine (11.87%), azathioprine (14.27%) and methotrexate (10.62%) (p < 0.05) (Table 5).

Treatment.

| With kidney involvement (n = 79) | Without kidney involvement (n = 81) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | p | |

| Prednisone | 74 | 93.67 | 69 | 85.18 | 0.137 |

| Methylprednisolone | 49 | 62.02 | 13 | 16.04 | 0.000 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 6 | 7.59 | 19 | 23.45 | 0.005a |

| Chloroquine | 47 | 59.49 | 43 | 53.08 | 0.414 |

| Azathioprine | 5 | 6.32 | 23 | 28.39 | 0.000a |

| Methotrexate | 0 | 0.00 | 17 | 20.98 | 0.000a |

| Mycophenolate | 56 | 70.88 | 29 | 35.80 | 0.000 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 23 | 29.11 | 4 | 4.93 | 0.000a |

| Tacrolimus | 1 | 1.26 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.494a |

| Deflazacort | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 3.70 | 0.127a |

| Leflunomide | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.23 | 0.506a |

| Belilumab | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.62 | 0.506a |

| Renal replacement therapy | 15 | 9.37 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.000a |

p: χ2.

LN is a common complication in patients with SLE, and its prevalence varies depending on the race. In Asian countries, its presence has been reported in 40–80%, in the Hispanic population in 40–60%, in the African population in 50–60%, in the European in 20–45% and in Caucasians in 14–23%.11–14 In this study of patients belonging to the LUPUS-IMMex cohort of the Hospital de Especialidades de Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, the prevalence was 49.37%, similar to that already reported in the Hispanic, Asian, and African populations. Gui et al., in an Asian cohort of 8,713 patients with SLE, found that males developed LM more frequently than females (43.60 vs. 36.20%),15 just like that was reported in a European cohort where LN affects more men than women (61 vs. 32%).16 In our research this trend does not change and, although the result did not have statistical significance, the condition in men corresponds to 51.72% and in women to 48.85%.

In the present study, arterial hypertension was more frequent in women with lupus nephropathy (33 vs. 10%, p = 0.001). Due to the role of the kidney in the control of the blood pressure, the patients who debuted with LN had a higher prevalence of systemic arterial hypertension. There is a complex interaction between genes, sex hormones and the environment in the development of arterial hypertension in SLE, local mediators (such as cytokines and reactive oxygen species) contribute to local inflammation that ultimately negatively affects the renal function.17 The variation in renal hemodynamics, due to direct damage at the glomerular and tubular level, alters the renal capacity to excrete sodium and water, with subsequent hydrosalpinx retention, which contributes to the development of hypertension.18 On the other hand, vascular dysfunction, which has been indirectly demonstrated (by brachial artery flow measurements) in patients with SLE, is associated with accelerated atherosclerosis, which favors the development of hypertension.19 SLE is a chronic autoimmune disorder that predominantly affects women of reproductive age. Various studies have demonstrated that there are alterations in the metabolism of endogenous estrogens that can affect the immune system and increase the production of cytokines, leading to endothelial dysfunction and, therefore, alterations in the blood pressure.20

In patients with SLE, infections are largely considered a complication of the immunosuppressive treatment. In the study by Wang et al.,21 a prevalence of 25.9% of severe infections was reported in the first 12 months after the diagnosis of SLE, even in the absence of immunosuppressive therapy, and a lymphocyte count <1.0 × 109/L was found as a risk factor. In our study, the prevalence of infections at the time of the diagnosis of SLE was higher in the population without LN, while the most frequent infections were viral (SARS-CoV-19 infection, influenza, hepatitis A, human papillomavirus and dengue). The concomitant occurrence of infectious processes and allergies at the time of the diagnosis of SLE could be related to intrinsic factors, which include dysfunction of the immune system characterized by alteration in chemotaxis and abnormal production of T cells.22 Wang et al.21 described as risk factors for the development of infections in the first four months after the onset of SLE, regardless of immunosuppressive treatment, a SLE disease activity index >10 points, a peripheral lymphocyte count <0.8 × 109/L and a serum creatinine >9 mg/dL. In our study, the EULAR score among the patients with infections ranged between 13–35 points and only 33% had lymphocytes lower than <0.8 × 109/L; in addition, infectious processes were more frequent in patients without kidney damage.

Regarding the EULAR 2019 classification criteria for SLE, the presence of arthritis and oral ulcers was documented with greater recurrence in the group of patients without renal involvement; on the other hand, the presence of hypocomplementemia and serositis (pleural or pericardial effusion) was more frequent in the group with renal involvement. Our findings were similar to those reported by Zhao et al.23 in a Chinese cohort of 2,104 patients, in which the prevalence of LN, leukocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypocomplementemia, and double-stranded DNA antibodies (anti-dsDNA) was significantly higher in patients with serositis (p < 0.05). It usually reflects the activity of SLE in general, so its association in those with LN is not uncommon.

Although the proportion of patients who debut concomitantly with renal involvement and joint manifestations is lower, this relationship has a prognostic status to the evolution and progression of the disease. Ginzler et al. consider that the presence of arthritis at the time of the diagnosis is a significant predictor of the progression of lupus nephritis (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.13; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.14–3.97; p = 0.018).24 On the other hand, in the study conducted by Kaplan et al., they found that patients with a positive rheumatoid factor are less likely to develop nephritis than those with a negative rheumatoid factor and without arthralgia.25,26 Li et al.27 establish that there is a greater number of people with rheumatoid arthritis concomitant with the diagnosis of SLE in patients without renal involvement. (5 vs. 26%, p < 0.05).

Hypocomplementemia is a common characteristic in the population with a diagnosis of SLE. In this sense, we were able to identify a notable tendency towards the coexistence of this characteristic at the expense of serum levels of C3 in the LN group, which coincides with various studies that report results similar to ours and attribute this association to the severity of the disease.28 Likewise, patients with hypocomplementemia also have a higher prevalence of proteinuria, hematuria, decreased kidney function, and disease activity compared to those with normal complement levels.29 Chen et al. propose the theory that this phenomenon is due to an overexpression of the alternative complement pathway at the glomerular level by a overexpression of factor B. which demonstrates that when using LNP023, a molecule capable of inhibiting the overexpression of factor B, the debut of the patients with kidney disease is less frequent.30

It is expected that in subjects with LN, the levels of serum protein and lipid profiles are altered to a greater extent than in those with SLE without LN, given the pathophysiology of the nephrotic and nephritic syndrome, renal manifestations characteristic of patients with LN. In those in whom nephrotic syndrome predominates, there is an increase in the synthesis of cholesterol and triglycerides at the hepatic level, with alteration of the lipid profile.31

The remission induction treatment established by the international guidelines mentions the use of pulses of methylprednisolone followed by mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide according to the chosen scheme and, subsequently, maintenance treatment with mycophenolate or azathioprine.32,33 In our study, these drugs were the most commonly used in the group of patients who debuted with renal activity, in accordance with the international guidelines in force at the time.

ConclusionsThe sociodemographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics of the patients who presented LN at the time of SLE diagnosis in our cohort are similar to those described in Latin and Asian series, since these are the groups in which SLE manifests itself more aggressively. To our knowledge, the presence of concomitant infections at the time of diagnosis in patients with SLE has not been described and should be considered for future research.

Ethical considerationsThe protocol was submitted and approved by the research and ethics committee of the Hospital de Especialidades del Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI.

FundingThis work has not received any type of funding.