Tofacitinib is an oral Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

ObjectiveTo conduct a post hoc analysis of tofacitinib efficacy and safety in Colombian patients enrolled in global phase III studies.

MethodsData were pooled from Colombian patients with RA across four phase III tofacitinib studies: ORAL Sync, ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo, and ORAL Start. Patients received tofacitinib 5 or 10mg twice daily, methotrexate (ORAL Start only), or placebo as single therapy (ORAL Start and ORAL Solo), or in combination with csDMARDs (ORAL Sync and ORAL Scan). Data were pooled from three studies with similar patient populations (Sync, Scan, Solo) for efficacy analyses, and from all studies for safety analyses, up to Month 24. The efficacy analysis excluded ORAL Start due to the methotrexate-naive patient population, and placebo and methotrexate groups, due to low patient numbers.

ResultsData pooled included 77 patients for efficacy, and 125 for safety analyses. Tofacitinib-treated patients showed improved American College of Rheumatology 20/50/70 response rates, a mean Disease Activity Score 28-4 (erythrocyte sedimentation rate), and a mean change from baseline in Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index. Improvements were sustained in Months 12–24, although patient numbers were low post-Month 12. The most frequently reported adverse events were anemia, headache, influenza, and increased blood creatine phosphokinase. No tuberculosis cases, serious adverse events, or deaths were reported, and few cases of herpes zoster or malignancies occurred.

ConclusionsTofacitinib reduced RA signs and symptoms, and improved physical function. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in this Colombian sub-population were consistent with data from global phase III studies.

Tofacitinib es un inhibidor oral de la janus kinasa para el tratamiento de la artritis reumatoide (AR).

ObjetivoAnálisis post hoc para evaluar la eficacia y seguridad de tofacitinib en los pacientes colombianos que participaron en los estudios globales de fase III.

MétodosLa información se obtuvo de los pacientes colombianos con AR que participaron en 4 de los estudios de tofacitinib de fase III: ORAL Sync, ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo y ORAL Start. Los pacientes recibieron tofacitinib 5 o 10mg 2 veces al día, ya sea en monoterapia (ORAL Start y ORAL Solo) o en combinación con csDMARDs (ORAL Scan y ORAL Sync), metotrexate (ORAL Start) o placebo. Para el análisis de eficacia se utilizaron 3 estudios que incluyeron poblaciones similares (Sync, Scan y Solo) y para el análisis de seguridad se utilizaron todos los estudios, hasta el mes 24. El análisis de eficacia excluyó tanto el estudio ORAL Start debido a población metotrexate naive como a los grupos placebo o metotrexate debido al bajo número de pacientes.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 77 pacientes para el análisis de eficacia y 125 para seguridad. Los pacientes tratados con tofacitinib mostraron mejorías en las tasas de respuestas del American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20/50/70, en el promedio del Disease Activity Score (DAS) 28-4 (velocidad de sedimentación globular) y en el cambio promedio desde la basal en el Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI). Las mejorías fueron sostenidas desde el mes 12 al mes 24, aunque el número de pacientes luego del mes 12 fue bajo. Los eventos adversos más frecuentemente reportados fueron anemia, cefalea, influenza e incremento de la creatin-fosfoquinasa sérica. No se reportaron casos de tuberculosis, eventos adversos serios o muertes. Ocurrieron casos poco frecuentes de herpes zoster y malignidades.

ConclusionesTofacitinib redujo los signos y síntomas de la AR y mejoró la función física. La eficacia y seguridad en esta subpoblación colombiana fue consistente con los resultados de los pacientes que participaron en los estudios globales de fase III.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a debilitating autoimmune disease that leads to chronic inflammation and destruction of the joints and surrounding tissues of the musculoskeletal system. Conservative estimates suggest that the prevalence rates for RA in the Latin American population (as a whole) range from 0.4% to 1.6%.1 A recent review of the epidemiology of RA in Colombia used medical records data to estimate the disease prevalence in Colombia to be 0.15%,2 and an analysis of RA prevalence specifically for African Colombians from Quibdo observed a period prevalence rate of 0.01%.3 However, a report from 2005 administrative sources estimated an overall Colombian prevalence of 0.9%.4 These low and varying prevalence rates may be due to genetic factors, under-diagnosis and reduced access to treatment.

Consistent with European and US guidelines,5,6 Latin American specific guidelines (Pan-American League of Associations for Rheumatology [PANLAR] and Grupo Latinoamericano de Estudio de Artritis Reumatoide [GLADAR]) state that RA treatment should control inflammation, minimize joint destruction and radiographic progression, preserve functional and work capabilities and improve quality of life.7 However, clinical management of RA in Latin American countries is subject to several challenges. For example, patient referral to specialist rheumatologists may be restricted or delayed, access to cost-effective medication, medical resources and public health services may be limited, and there is a lack of public policies and education surrounding RA.1,7–10 Early diagnosis and treatment is important for slowing the structural progression of RA11; however, in a survey of Colombian rheumatologists, 48.6% of respondents considered early RA to represent the first 3 months after onset of symptoms, yet 54.5% believed that patients were not referred to specialists until between 3 and 6 months after symptom onset.12

For patients with RA in Colombia, first-line treatment generally consists of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), followed by biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, for patients who do not show an adequate response to initial treatment.13–16 Screening for latent TB prior to initiation of bDMARDs is recommended in Latin American guidelines.7 As the incidence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) in Colombia is intermediate at 31 (range 24–39) cases per 100,000 population; both screening and monitoring for occurrence of TB during treatment is important in the Colombian patient population.17 In Colombia, tofacitinib is recommended in adult patients with RA after failure to csDMARDs or biologic therapy.16

Although bDMARDs have not previously been commonly prescribed in Colombia,2,12 a recent retrospective study has shown an increasing number of prescriptions for bDMARDs among the study cohort of patients with RA, with more than one-quarter receiving bDMARDs by the end of the study, with etanercept and abatacept the most frequently used.15 In the Colombian patient population, infliximab and adalimumab have previously been shown to improve functional capacity and quality of life in patients with refractory RA.18,19 However, traditionally, the low prescription of bDMARDs may be a consequence of the high costs associated with bDMARDs, and the requirement for close clinical and serologic monitoring of patients. A recent Colombian cross-sectional study showed that from one-third to half of patients attending a specialized care clinic were in remission according to disease activity score (DAS28 <2.6; DAS erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] 34.1% and DAS28 C-reactive protein [CRP] 49.5%),13 although it is important to note that acute phase reactant levels may not always reflect disease activity.20 A Colombian retrospective cohort analysis showed 42.9% of patients achieving remission defined as DAS28 ≤2.6,15 highlighting a requirement for alternative RA therapies. Moreover, although this remission rate may seem high, remission rates using different parameters, such as Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data (RAPID), Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI), often show lower remission rates.21,22

Tofacitinib is an oral Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of RA. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 and 10mg twice daily (BID) have been demonstrated in patients with moderately to severely active RA and various treatment histories in randomized global phase II23–28 and phase III29–34 studies of up to 24 months’ duration, and in long-term extension (LTE) studies with up to 114 months of observation.35–37 Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib specifically in Latin American populations have been analyzed previously in Phase III and LTE studies, due to differences in epidemiology and treatment guidelines compared with global populations. 38,39 In this post hoc analysis, the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID was evaluated in a subpopulation of Colombian patients included in the global phase III studies in RA.

MethodsPatientsThis analysis included data from Colombian patients enrolled in four global phase III studies of tofacitinib for the treatment of RA. Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria have previously been reported in detail for each individual study.16,29–31,33 In summary, eligible patients were aged ≥18 years and had a diagnosis of moderately to severely active RA based on American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20/50/70 response rate criteria.40 Patients were excluded if they had recent, current or serious chronic infections; active or inadequately treated latent TB infection; history of recurrent herpes zoster, disseminated herpes zoster, or disseminated herpes simplex; hepatitis B or C; human immunodeficiency virus; evidence or history of malignancy, other than adequately treated or excised non-metastatic basal or squamous cell cancer of the skin, or cervical carcinoma in situ; and evidence or history of lymphoma or lymphoproliferative disease.

Study designsData were analyzed from four phase III double-blind, randomized, controlled studies of 6–24 months’ duration that included patients from Colombia: ORAL Sync [NCT00856544; 12 months],30 ORAL Scan [NCT00847613; 24 months],31 ORAL Solo [NCT00814307; 6 months]29 and ORAL Start [NCT01039688; 12-month data-cut, study was ongoing, database not locked].33 These studies included patients who had previously had an inadequate response to methotrexate (ORAL Scan), or ≥1 bDMARD or csDMARD (ORAL Sync and ORAL Solo). Patients enrolled in ORAL Start were naïve to methotrexate treatment (defined as no prior treatment or ≤3 weekly doses). In ORAL Scan, ORAL Sync and ORAL Solo, patients were randomized to receive tofacitinib 5mg BID, tofacitinib 10mg BID, placebo advanced to tofacitinib 5mg BID, or placebo advanced to tofacitinib 10mg BID. In the ORAL Sync and ORAL Scan studies, placebo patients who did not achieve ACR20 at Month 3 were advanced to tofacitinib treatment according to randomization. All remaining placebo patients advanced to tofacitinib treatment at Month 6. All placebo patients advanced to tofacitinib treatment at Month 3 in ORAL Solo. In ORAL Start, patients were randomized to receive tofacitinib 5mg BID, tofacitinib 10mg BID, or methotrexate 10mg per week titrated to 20mg per week over the course of 8 weeks, and maintained for the duration of the study. Study drug was administered either as monotherapy (in ORAL Solo and ORAL Start), or in combination with background methotrexate (ORAL Scan) or csDMARDs (ORAL Sync). Further information on study initiation, completion dates and Principal Investigators is shown in Supplementary Table 4.

All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, and were approved by Institutional Review Boards and/or Independent Ethics Committees at each of the investigational centers participating in the study. All patients provided written informed consent.

Efficacy endpointsEfficacy endpoints assessed up to Month 24 included: ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 response rates; mean Disease Activity Score (DAS)28-4 (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]) scores; and mean change from baseline in Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) scores.

Safety endpointsEndpoints included reporting of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs, discontinuations due to AEs, and mortality cases. Malignancy events were adjudicated by an independent adjudication committee, which carried out a blinded review of each biopsy case with at least two independent, board-certified pathologists. Major cardiovascular AEs and all deaths were adjudicated by a blinded, independent, external cardiovascular safety endpoint adjudication committee for all phase III studies. Patients were screened for latent or untreated TB before enrollment, in accordance with the protocol for patients using bDMARDs in other Latin American countries.41,42 All available safety data were analyzed up to Month 24.

Statistical analysisAll efficacy and safety analyses were based on observed cases (i.e. no imputation of missing values) in the full analysis set (FAS), which included all patients who were randomized and received at least one dose of study treatment (tofacitinib, placebo or methotrexate). Efficacy analyses were assessed using FAS pooled data from three studies (ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo and ORAL Sync). Patients from ORAL Start were not included in efficacy analyses as they were a methotrexate-naïve population, and therefore represented a different patient population versus the populations in the other three studies. Efficacy data are reported for tofacitinib groups only, as patient numbers in the placebo and methotrexate groups were too low for meaningful comparison. Safety analyses were performed on FAS data pooled from all four studies (ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo, ORAL Sync and ORAL Start). Despite low patient numbers in some groups, safety data are reported for all groups for completeness. All analyses were descriptive in nature, and general trends were described. Due to small sample sizes, no statistical hypothesis testing was performed; therefore, all differences described in the Results section refer to numerical differences only.

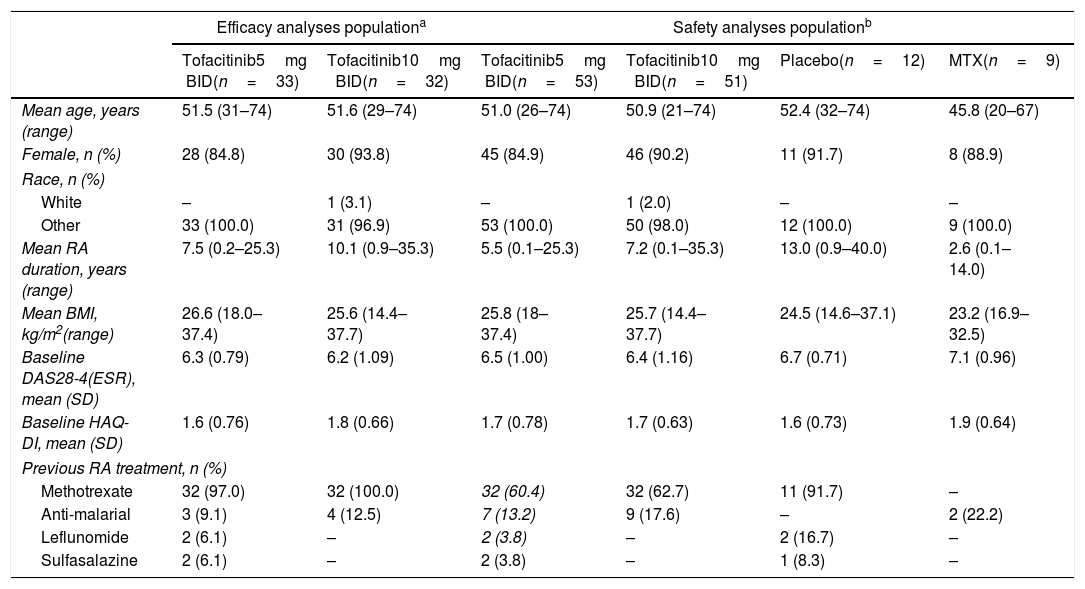

ResultsPatientsIn total, 77 Colombian patients from three studies (ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo and ORAL Sync) were included in the efficacy analysis, and 125 Colombian patients from four studies (ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo, ORAL Sync and ORAL Start) were included in the safety analyses. Baseline demographics and characteristics were generally similar across treatment groups within the efficacy and safety analyses populations, although in the safety population the mean duration of RA was higher in the placebo groups and both the mean duration of RA and mean age were lower in the methotrexate-treated groups versus the other treatment groups (Table 1).

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics by treatment sequence for patients included in the efficacy and safety analyses.

| Efficacy analyses populationa | Safety analyses populationb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tofacitinib5mg BID(n=33) | Tofacitinib10mg BID(n=32) | Tofacitinib5mg BID(n=53) | Tofacitinib10mg BID(n=51) | Placebo(n=12) | MTX(n=9) | |

| Mean age, years (range) | 51.5 (31–74) | 51.6 (29–74) | 51.0 (26–74) | 50.9 (21–74) | 52.4 (32–74) | 45.8 (20–67) |

| Female, n (%) | 28 (84.8) | 30 (93.8) | 45 (84.9) | 46 (90.2) | 11 (91.7) | 8 (88.9) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | – | 1 (3.1) | – | 1 (2.0) | – | – |

| Other | 33 (100.0) | 31 (96.9) | 53 (100.0) | 50 (98.0) | 12 (100.0) | 9 (100.0) |

| Mean RA duration, years (range) | 7.5 (0.2–25.3) | 10.1 (0.9–35.3) | 5.5 (0.1–25.3) | 7.2 (0.1–35.3) | 13.0 (0.9–40.0) | 2.6 (0.1–14.0) |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2(range) | 26.6 (18.0–37.4) | 25.6 (14.4–37.7) | 25.8 (18–37.4) | 25.7 (14.4–37.7) | 24.5 (14.6–37.1) | 23.2 (16.9–32.5) |

| Baseline DAS28-4(ESR), mean (SD) | 6.3 (0.79) | 6.2 (1.09) | 6.5 (1.00) | 6.4 (1.16) | 6.7 (0.71) | 7.1 (0.96) |

| Baseline HAQ-DI, mean (SD) | 1.6 (0.76) | 1.8 (0.66) | 1.7 (0.78) | 1.7 (0.63) | 1.6 (0.73) | 1.9 (0.64) |

| Previous RA treatment, n (%) | ||||||

| Methotrexate | 32 (97.0) | 32 (100.0) | 32 (60.4) | 32 (62.7) | 11 (91.7) | – |

| Anti-malarial | 3 (9.1) | 4 (12.5) | 7 (13.2) | 9 (17.6) | – | 2 (22.2) |

| Leflunomide | 2 (6.1) | – | 2 (3.8) | – | 2 (16.7) | – |

| Sulfasalazine | 2 (6.1) | – | 2 (3.8) | – | 1 (8.3) | – |

BID: twice daily; BMI: body mass index; DAS28-4(ESR): Disease Activity Score28-4(erythrocyte sedimentation rate); HAQ-DI: Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; Other: Black/Asian/Hispanic; MTX: methotrexate; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SD: standard deviation.

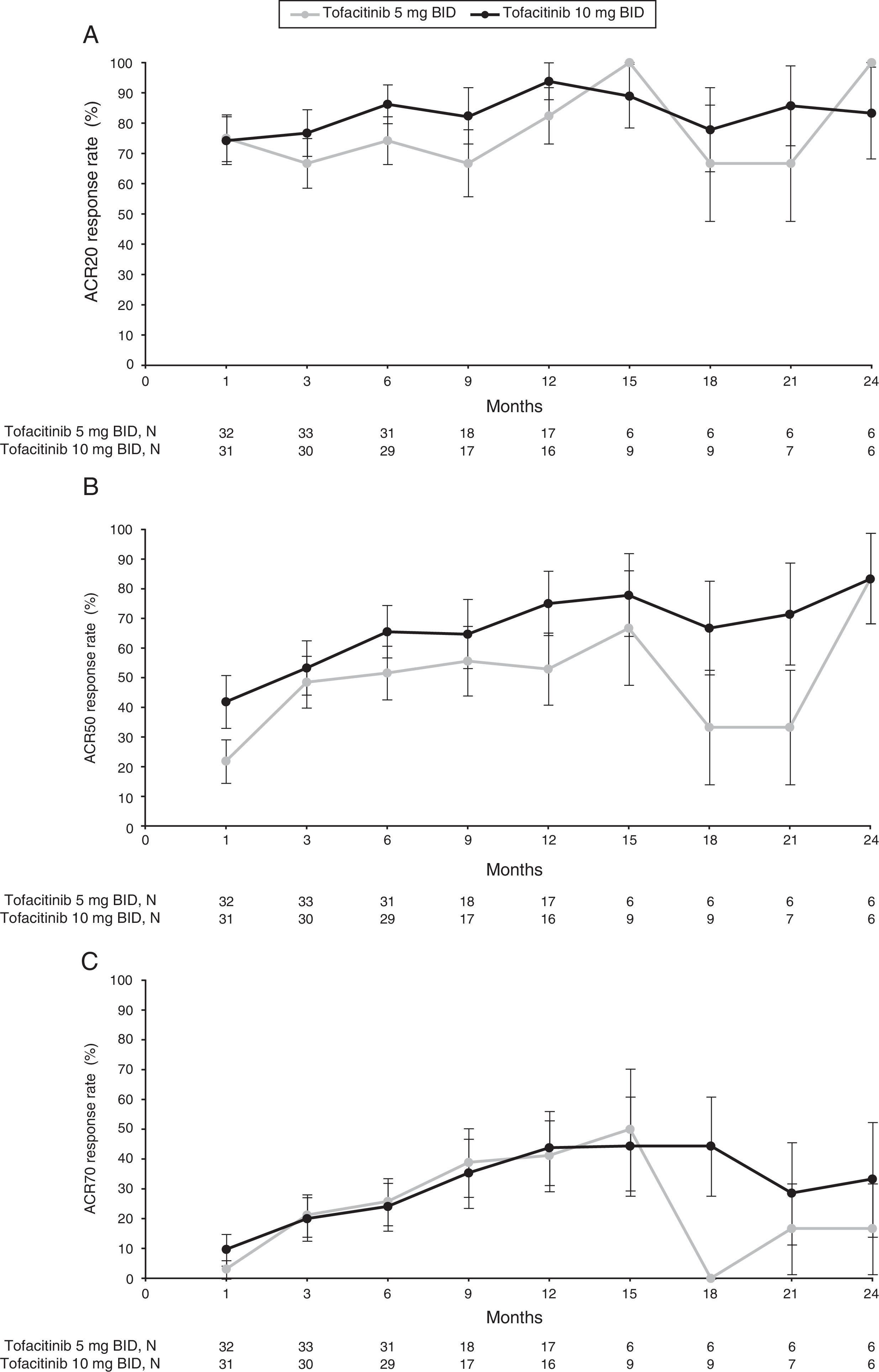

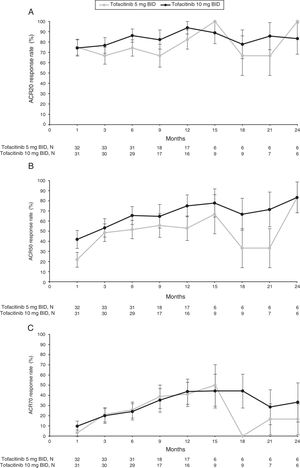

At Month 1, ACR20 response rates for both tofacitinib 5mg BID (75.0%) and tofacitinib 10mg BID (74.2%) were similar. Between Month 3 and Month 9, ACR20 responses ranged from 66.7–to 74.2% and 76.7–86.2% for tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID, respectively (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 1). By Month 12, ACR20 response rates for both tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID groups improved further (82.4% and 93.8%, respectively). Therefore, although patient numbers reduced after Month 6, ACR20 response rates across all treatment groups were generally sustained to Month 12 (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 1). After Month 12, patient numbers were low; however, improvements in ACR20 responses appeared to be generally sustained through Month 24 (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 1).

Proportion of responders for (A) ACR20, (B) ACR50 and (C) ACR70 (SE) over time for the tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID groups in the efficacy subpopulation (FAS, observed).

ACR20/50/70: American College of Rheumatology 20/50/70 response rates; BID: twice daily; FAS: full analysis set; SE, standard error.

N represents the numbers of patients with non-missing ACR response. Efficacy analyses were based on three studies: ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo and ORAL Sync.

ACR50 response improved over time for both tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID groups from Month 1 (21.9% and 41.9%, respectively), and from Month 3 (48.5% and 53.3%, respectively) through to Month 12 (52.9% and 75.0%, respectively) (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table 1). Tofacitinib 10mg BID appeared to show higher ACR50 responses than tofacitinib 5mg BID, although no formal statistical analysis was performed. From Month 12 to Month 24, patient numbers were low for both tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID groups, and ACR50 responses ranged from 33.3–83.3% and 66.7–83.3%, respectively (Fig. 1B and SupplementaryTable 1).

Similarly, ACR70 response rates improved over time for both tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID groups from Month 1 (3.1% and 9.7%, respectively), and from Month 3 (21.2% and 20.0%, respectively) through to Month 12 (41.2% and 43.8%, respectively) (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Table 1). ACR70 responses were comparable among both tofacitinib groups from Month 3 to Month 12. From Month 12 to Month 24, ACR70 responses varied over time with tofacitinib 5mg BID (0–50.0%), and were generally sustained with tofacitinib 10mg BID (28.6–44.4%); however, patient numbers for these time points were low (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Table 1).

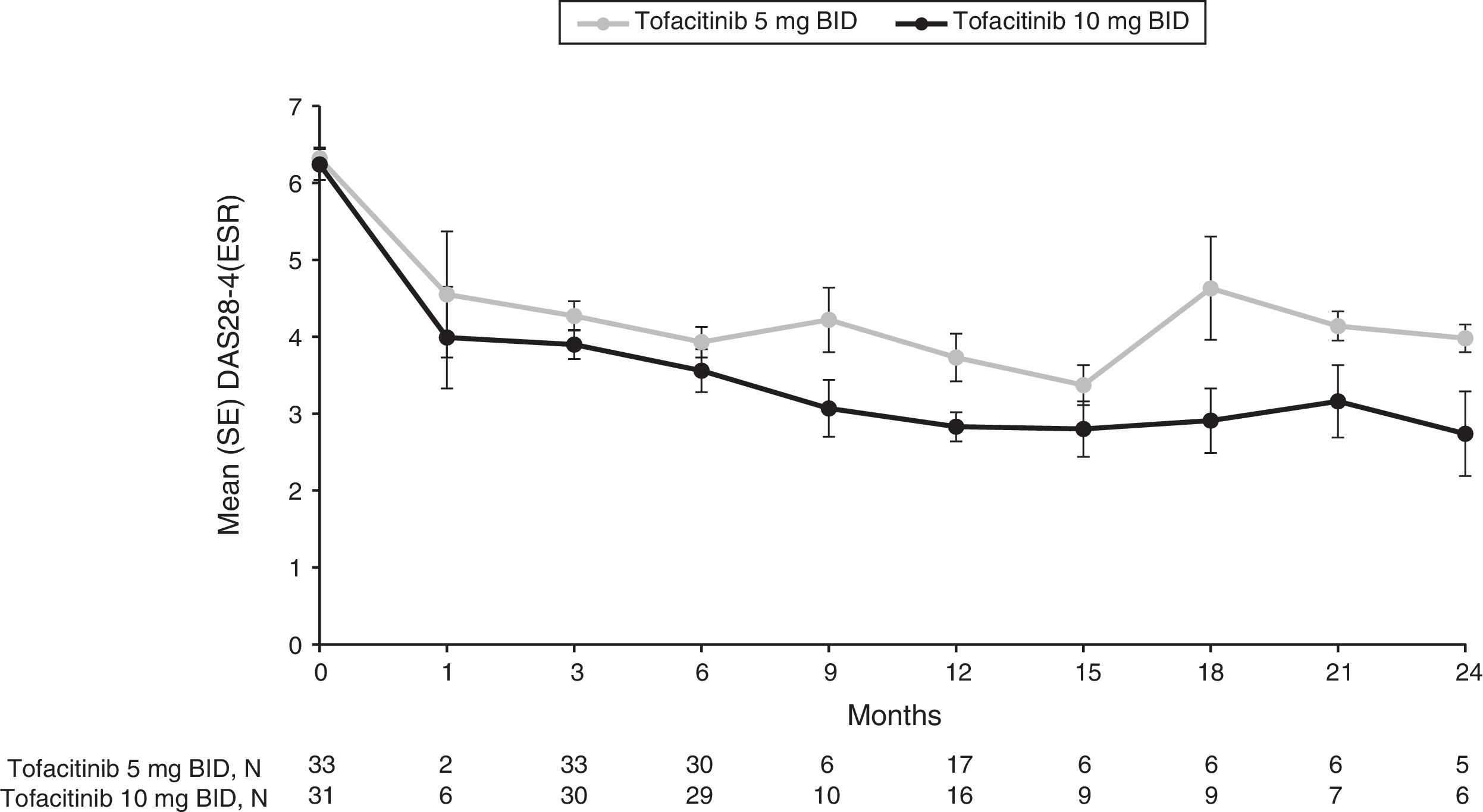

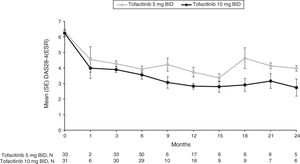

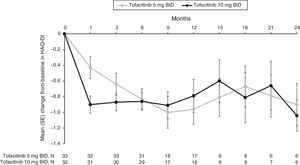

Mean DAS28-4(ESR) steadily improved over time for both tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID groups from baseline (6.3 and 6.2, respectively), to Month 1 (4.6 and 4.0, respectively), to Month 3 (4.3 and 3.9, respectively) and through to Month 12 (3.7 and 2.8, respectively) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). Although patient numbers were low after Month 12, improvements in mean DAS28-4(ESR) appeared to be generally sustained through to Month 24 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2).

Mean (SE) DAS28-4(ESR) over time for the tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID groups in the efficacy subpopulation (FAS, observed).

BID: twice daily; DAS28-4(ESR): Disease Activity Score-erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FAS: full analysis set; SE: standard error.

N represents the numbers of patients with non-missing DAS28-4(ESR). Efficacy analyses were based on three studies: ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo and ORAL Sync.

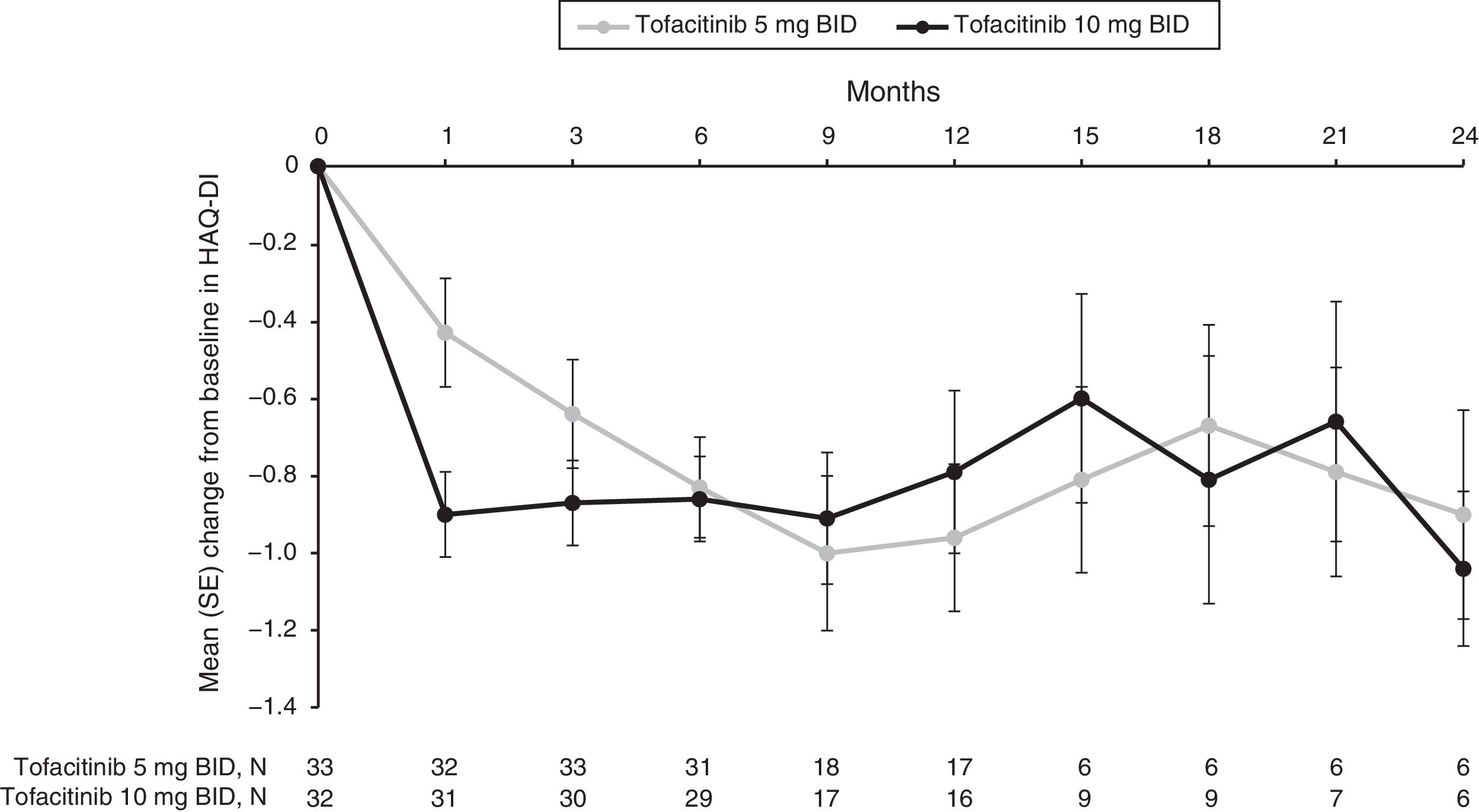

Improvements from baseline in mean HAQ-DI scores were observed for both tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID groups as early as Month 1 (−0.4 and −0.9, respectively), and were sustained over time to Month 3 (−0.6 and −0.9) through to Month 12 (−1.0 and −0.8) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 3). Although patient numbers were low after Month 12, improvements in mean HAQ-DI scores appeared to be generally sustained through to Month 24 (−0.9 and −1.0, respectively).

Mean (SE) change from baseline in HAQ-DI (SE) over time for the tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID groups in the efficacy subpopulation (FAS, observed).

BID: twice daily; FAS: full analysis set; HAQ-DI: Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; SE: standard error.

N represents the numbers of patients with non-missing HAQ-DI. Efficacy analyses were based on three studies: ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo and ORAL Sync.

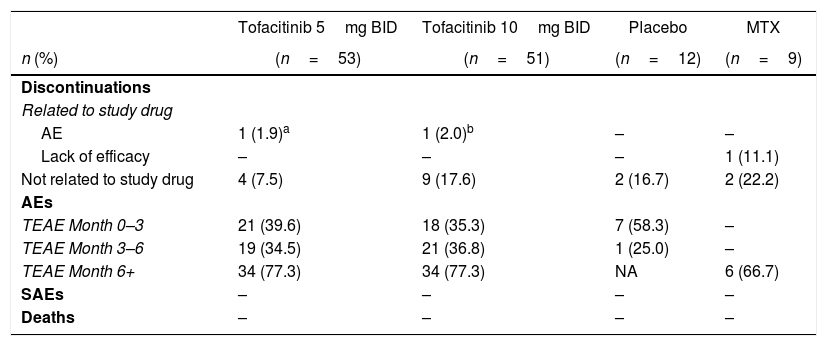

In total, 15 patients receiving tofacitinib treatment discontinued from the studies; 13 of these discontinuations were considered unrelated to study drug, and two patients (one each in the tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID groups) discontinued due to AEs related to study drug (Table 2). No serious AEs or deaths were reported in any treatment group. A higher proportion of patients reported treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) after Month 6 compared with the Month 0–3 and Month 3–6 treatment periods (Table 2).

Summary of safety outcomes for all treatment groups.

| Tofacitinib 5mg BID | Tofacitinib 10mg BID | Placebo | MTX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | (n=53) | (n=51) | (n=12) | (n=9) |

| Discontinuations | ||||

| Related to study drug | ||||

| AE | 1 (1.9)a | 1 (2.0)b | – | – |

| Lack of efficacy | – | – | – | 1 (11.1) |

| Not related to study drug | 4 (7.5) | 9 (17.6) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (22.2) |

| AEs | ||||

| TEAE Month 0–3 | 21 (39.6) | 18 (35.3) | 7 (58.3) | – |

| TEAE Month 3–6 | 19 (34.5) | 21 (36.8) | 1 (25.0) | – |

| TEAE Month 6+ | 34 (77.3) | 34 (77.3) | NA | 6 (66.7) |

| SAEs | – | – | – | – |

| Deaths | – | – | – | – |

AE: adverse event; BID: twice daily; MTX: methotrexate; NA: not applicable; SAE, serious adverse event; TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event.

Patient discontinued due a persistent elevation in function liver tests (alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyltransferase), but not adjudicated SAE

Placebo patients advanced to tofacitinib 5 or 10mg BID at Month 3 or 6, depending on American College of Rheumatology 20 response rate.

Safety analyses were based on data from four studies: ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo, ORAL Sync and ORAL Start.

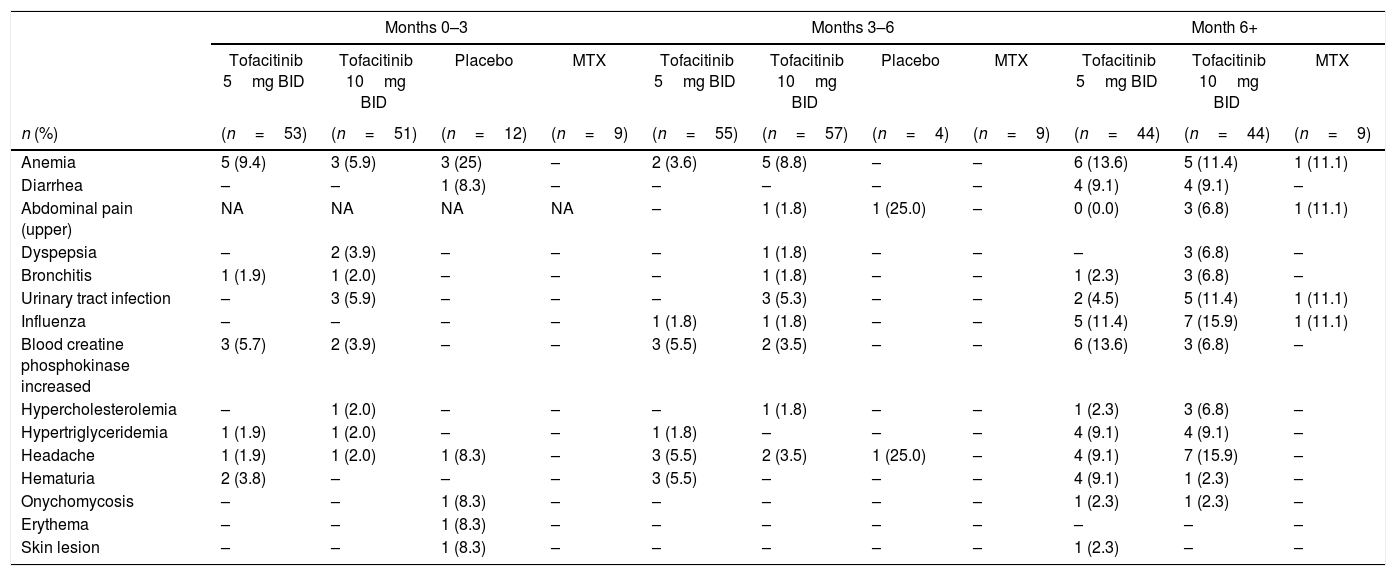

During the first 3 months of treatment, the most frequently reported TEAEs were anemia for the placebo and tofacitinib 5mg BID groups, and anemia and urinary tract infection for the tofacitinib 10mg BID group; no TEAEs were reported in the methotrexate group (Table 3). One case each of hypotension and hematoma were with tofacitinib 5mg BID and one case of hypertensive crisis was reported with tofacitinib 10mg BID. Between Months 3 and 6, the most frequently reported TEAEs were hematuria, headache and increased blood creatine phosphokinase with tofacitinib 5mg BID, and anemia with tofacitinib 10mg BID. One case of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC; basal cell carcinoma) malignancy was reported in the tofacitinib 10mg BID group between Months 3 and 6. No TEAEs were reported in patients receiving methotrexate, and no particular TEAE was more frequent in the placebo group. Post-Month 6, the most frequently reported TEAEs for tofacitinib-treated patients were anemia, headache, influenza and increased blood creatine phosphokinase; no particular TEAE was more frequent in the methotrexate group (Table 3). Differences were observed between AEs reported for patients receiving tofacitinib 5 or 10mg BID post-6 months, with a higher number of reported headaches, influenza and gastrointestinal disorders (upper abdominal pain and dyspepsia) in patients receiving tofacitinib 10mg BID compared with those receiving tofacitinib 5mg BID. Post-Month 6, there was one other reported case of NMSC (basal cell carcinoma) malignancy in the tofacitinib 10mg BID group, and a single reported case of herpes zoster in the tofacitinib 5mg BID group; no other cases of herpes zoster were reported. One case each of tachycardia was reported with tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID, respectively. There were no reported cases of TB, opportunistic infections, serious infections or gastrointestinal perforations.

Most frequently reported TEAEs (≥5%) in any treatment group.

| Months 0–3 | Months 3–6 | Month 6+ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tofacitinib 5mg BID | Tofacitinib 10mg BID | Placebo | MTX | Tofacitinib 5mg BID | Tofacitinib 10mg BID | Placebo | MTX | Tofacitinib 5mg BID | Tofacitinib 10mg BID | MTX | |

| n (%) | (n=53) | (n=51) | (n=12) | (n=9) | (n=55) | (n=57) | (n=4) | (n=9) | (n=44) | (n=44) | (n=9) |

| Anemia | 5 (9.4) | 3 (5.9) | 3 (25) | – | 2 (3.6) | 5 (8.8) | – | – | 6 (13.6) | 5 (11.4) | 1 (11.1) |

| Diarrhea | – | – | 1 (8.3) | – | – | – | – | – | 4 (9.1) | 4 (9.1) | – |

| Abdominal pain (upper) | NA | NA | NA | NA | – | 1 (1.8) | 1 (25.0) | – | 0 (0.0) | 3 (6.8) | 1 (11.1) |

| Dyspepsia | – | 2 (3.9) | – | – | – | 1 (1.8) | – | – | – | 3 (6.8) | – |

| Bronchitis | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.0) | – | – | – | 1 (1.8) | – | – | 1 (2.3) | 3 (6.8) | – |

| Urinary tract infection | – | 3 (5.9) | – | – | – | 3 (5.3) | – | – | 2 (4.5) | 5 (11.4) | 1 (11.1) |

| Influenza | – | – | – | – | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.8) | – | – | 5 (11.4) | 7 (15.9) | 1 (11.1) |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 3 (5.7) | 2 (3.9) | – | – | 3 (5.5) | 2 (3.5) | – | – | 6 (13.6) | 3 (6.8) | – |

| Hypercholesterolemia | – | 1 (2.0) | – | – | – | 1 (1.8) | – | – | 1 (2.3) | 3 (6.8) | – |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.0) | – | – | 1 (1.8) | – | – | – | 4 (9.1) | 4 (9.1) | – |

| Headache | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (8.3) | – | 3 (5.5) | 2 (3.5) | 1 (25.0) | – | 4 (9.1) | 7 (15.9) | – |

| Hematuria | 2 (3.8) | – | – | – | 3 (5.5) | – | – | – | 4 (9.1) | 1 (2.3) | – |

| Onychomycosis | – | – | 1 (8.3) | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | – |

| Erythema | – | – | 1 (8.3) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Skin lesion | – | – | 1 (8.3) | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (2.3) | – | – |

BID: twice daily; MTX: methotrexate; NA: not applicable; TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event.

Placebo patients could advance to tofacitinib 5 or 10mg BID at Month 3 depending on American College of Rheumatology 20 response rate; all remaining placebo patients advanced at Month 6 to tofacitinib 5 or 10mg BID. Abdominal pain upper was not listed for Month 0–3.

Safety analyses were based on data from four studies: ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo, ORAL Sync and ORAL Start.

This post hoc analysis of the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in Colombian patients with RA demonstrated that tofacitinib 5mg BID and tofacitinib 10mg BID reduced the signs and symptoms of RA, as measured by ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 response rates and mean DAS28-4(ESR), and improved physical function, as measured by mean change from baseline in HAQ-DI. Although patient numbers were low post-Month 12, efficacy improvements were generally sustained through to Month 24 in the tofacitinib 5 and 10mg BID groups. Demographics were generally similar among the Colombian populations studied here and the global data, with the exception of race, where the majority of Colombian patients were non-white; however, additional analysis of this category was not conducted. Mean RA duration was generally slightly shorter (excluding placebo which was higher) and HAQ-DI was generally higher in the data reported here, compared with global data for these studies.29–34,38,39

Similar improvements in efficacy outcomes at Month 3 were observed for Colombian patients receiving tofacitinib 5mg BID and tofacitinib 10mg BID, compared with the Latin American population in tofacitinib phase III studies and generally similar efficacy outcomes compared with LTE studies.38 The efficacy analyses presented here showed that ACR response rates, change from baseline in HAQ-DI, and mean DAS28-4(ESR) were also generally similar compared with the global phase III RA population.29–34,38

Unlike many bDMARDs, which require subcutaneous or intravenous administration, tofacitinib is administered orally. This may be particularly beneficial in Colombia, where some patients may not have easy access to resources related to transportation, storage and administration of these medications. However, patients receiving tofacitinib do require routine monitoring of neutrophils, lymphocytes, hemoglobin, liver enzymes and lipids, as well as baseline screening for TB and viral hepatitis. 43 Our results for Colombian patients with RA support the global findings that tofacitinib could provide an effective oral alternative to bDMARDs.

There were no reported cases of serious AEs, serious infections, or deaths in any of the treatment groups, and the overall safety profile of tofacitinib was generally similar between the Colombian subpopulation and both the global phase III RA population29–34 and the Latin American population.38 However, in interpreting these findings it is important to acknowledge that the global and Latin American populations included a larger number of patients, with greater total tofacitinib exposure analyzed, compared with the Colombian subpopulation. Two cases of NMSC malignancies were reported in the tofacitinib 10mg BID group. No cases of lymphoma, or lymphoproliferative disorders were reported in Colombian patients.

No cases of TB were reported in this Colombian subpopulation, which is consistent with the low incidence reported in the Latin American and global phase III and LTE populations. 29-34,38,39,44 It is important to note that patients enrolled into tofacitinib clinical trials were screened for latent or untreated TB before enrollment, and it is recommended that all patients (including those from countries where TB is not endemic) should be screened for TB before initiating tofacitinib treatment, as is already the case for patients using bDMARDs in other Latin American countries.41,42 Furthermore, previous reports have indicated that the risk of developing TB while receiving immunosuppressant therapy varies according to the background TB rate in the underlying population.44–47 The latest World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report listed incidence of TB in Colombia as intermediate, therefore monitoring for TB as a possible AE of special interest was important in this population.17

Overall, fewer AEs, serious AEs and deaths were reported for the Colombian subpopulation compared with the Latin American and global populations; however, this is most likely the result of the small sample size in the Colombian subpopulation.29–34,38,39 Investigator-reported increases in blood creatine phosphokinase were observed in some patients receiving tofacitinib in this Colombian subpopulation; however, proportions of events were no higher than in the long-term extension studies in the Latin American population.38 Similarly, throughout the entire global RA program generally, mean values for serum creatine phosphokinase remained within normal reference ranges.48

Treatment with bDMARDs can increase the risk of infections and infestations compared with csDMARDs in patients in Latin American countries.49,50 No opportunistic infections or serious infections were reported in this analysis of Colombian patients, and there was one case of non-serious herpes zoster in the tofacitinib 5mg BID group; however, it should be noted that the comparatively low Colombian patient numbers may not enable generalization to the wider population. In the global tofacitinib studies, increased rates of herpes zoster were observed with tofacitinib treatment compared with placebo, but reports of complicated herpes zoster events have been rare for tofacitinib-treated patients in longer-term studies.29–35,51 Therefore, there were no cases of TB, opportunistic infection, gastrointestinal perforation, or serious cardiovascular AEs, and few cases of herpes zoster or malignancies were reported in Colombian patients receiving tofacitinib in these phase III studies. However, it remains important to routinely monitor patients for these AEs, as is already recommended in Colombian guidelines for other immunosuppressant therapies.14,16

With the exception of ORAL Start, in which patients were MTX-naïve, the patient populations among ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo and ORAL Sync were generally very similar and were DMARD-IR. Therefore, this post hoc analysis was somewhat limited by the use of pooled data, which can provide a heterogeneous patient population. Moreover, there were some differences in designs and methodologies of the phase III studies included in this analysis. As such, efficacy analyses included patients from ORAL Scan, ORAL Solo and ORAL Sync only, as patients in ORAL Start were methotrexate-naïve, and represented a different patient population that was not directly comparable. A greater proportion of Colombian patients were identified as non-white compared with the global populations; however, further investigation of race within the non-white listing category was not conducted. At all time points, patient numbers in the placebo and methotrexate groups were too low to allow meaningful comparison to be made with the tofacitinib groups, and therefore the exclusion of these groups from efficacy analyses limits the interpretation of the findings. For completeness, placebo and methotrexate groups were included in the safety analysis; however, the placebo group was smaller and had shorter exposure than the tofacitinib groups, which limits meaningful between group comparisons. Another important limitation of this post hoc analysis is the low patient numbers for all groups post-Month 12. Due to these low patient numbers, efficacy outcomes for tofacitinib groups post-Month 12, and any safety differences between active treatment and placebo post-Month 12, should be interpreted with caution. Due to the small sample sizes of this analysis of the Colombian sub-population, no formal statistical analyses were conducted. Also analyses were not powered to identify differences in efficacy or safety between treatment groups, therefore, conclusions are not definitive and are based on descriptive analyses only.

ConclusionTwo studies observed that from one-third to half of patients with RA in Colombia may be achieving remission;13,15 as such, there may be an unmet clinical need in Colombia for new RA therapies that can improve treatment outcomes for patients who have an inadequate response to csDMARDs and bDMARDs. Our results suggest that tofacitinib 5mg BID and tofacitinib 10mg BID were efficacious over 12 months (Month 24 data also presented) for the treatment of RA in Colombian patients in phase III studies; this was consistent with the findings from the global phase III and Latin American populations.

The data presented here for the Colombian sub-population suggest that there are no major differences in terms of efficacy or safety compared with patients from Latin American or global populations. Therefore, no significant differential factor emerged between the Colombian populations and other populations, which may be important when considering that incidences of some infections and neglected tropical diseases are more frequent in Latin American countries.52,53

Both tofacitinib doses demonstrated a manageable safety profile in the Colombian subpopulation. Overall, our results support the favorable benefit-risk of tofacitinib as an oral alternative to bDMARDs for the treatment of patients with RA in Colombia.

FundingThis study was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Author roles and contributionsAll authors meet the criteria for authorship and have approved the final article.

Conflict of interestP Vélez and W Otero Escalante have no conflicts of interest to declare. JJ Jaller has no conflicts of interest to declare. EG García and K Persand were employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc at the time the studies were conducted. R Rojo, D Chapman, and G Matiz are employees of Pfizer Inc.

The authors would like to thank the patients, investigators and study teams involved in the studies included in this analysis. The authors would also like to thank Elaine Hoffman for providing statistical support. Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Rebecca Douglas, PhD, CMC Connect, a division of Complete Medical Communications Ltd, Macclesfield, UK and was funded by Pfizer Inc, New York, NY, USA in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2015;163:461–464). This analysis was previously presented in poster form at Asociación Colombiana de Reumatología Medellín, Colombia, August 15–18, 2013.54