Many patients use the internet as a source of health information and to create and share content of diverse quality of evidence, complementing and even competing with traditional sources of information.

ObjectivesTo evaluate differences between rheumatic patients who consult digital information sources (DISs) and those who do not (Non-DISs), and their perception of the credibility attributed to these sources by both groups.

Materials and MethodsAn observational cross-sectional study was conducted through an anonymous survey of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, and spondyloarthritis. Patients were asked about their search for information from different DISs or Non-DISs. Patients rated the credibility they assigned to the different sources on a scale of 0–10, where 0 was no credibility and 10 was the maximum possible credibility.

ResultsA total of 402 patients (79% female) were surveyed. Two hundred and seven (51%) had consulted at least one DIS during the previous year (DISs group). The DISs group had consulted a total of 5 DISs and Non-DISs (First-Third Quartile: 3–7) vs. 2 (First-Third Quartile: 1–3) in the Non-DISs group (P < .001). The number of searches in DISs was higher at younger ages (OR .97 95% CI .95–.99) and at higher levels of education (secondary vs. primary OR 2.0; 95% CI 1.05–3.85). The DISs group assigned higher credibility to Facebook and YouTube than the other patients (median credibility of 6/10 and 6/10 vs. 2/10 and 1/10 respectively; P < .001). However, they did not assign lower credibility to traditional sources.

ConclusionsDISs are more frequently consulted by a younger population with a higher level of education. These patients consult multiple sources, but do not assign lower credibility to traditional information sources.

Muchos pacientes utilizan internet como fuente de información sobre salud y para crear y compartir contenidos con diferente calidad de evidencia, que complementan incluso compiten con las fuentes tradicionales de información.

ObjetivosEvaluar diferencias entre pacientes reumáticos que consultan fuentes de información digitales (FID) y los que no lo hacen (NoFID) y las percepciones sobre la credibilidad que ambos grupos adjudican a estas fuentes.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional, transversal, mediante de una encuesta anónima, a pacientes con artritis reumatoide, lupus eritematoso sistémico, esclerosis sistémica y espondiloartritis. Se preguntó a los pacientes sobre la búsqueda de información en diferentes FID y NoFID. Cada paciente calificó la credibilidad que adjudicaba a las diferentes fuentes, en una escala de 0 a 10, donde 0 es ninguna credibilidad y 10 el máximo de credibilidad posible.

ResultadosSe encuestó a 402 pacientes (79% mujeres). Hubo 207 pacientes (51%) que habían consultado, al menos, a una FID en el año previo (Grupo FID). El Grupo FID había consultado en total 5 FID y NoFID (primer-tercer cuartil: 3–7) vs. 2 (primer-tercer cuartil: 1–3) en el Grupo NoFID (P < ,001). Las consultas a una FID fueron mayores a menor edad (OR 0,97, IC 95% 0,95−0.99) y a mayor nivel de educación (secundario vs. primario OR 2,0; IC 95% 1,05–3,85). El Grupo FID adjudicaba una mayor credibilidad a Facebook y YouTube que el resto (mediana de credibilidad de 6/10 y 6/10 vs. 2/10 y 1/10 respectivamente; P < ,001). Sin embargo, no adjudicaron una menor credibilidad que el resto a ninguna de las fuentes tradicionales.

ConclusionesLas FID son consultadas más frecuentemente por pacientes más jóvenes y que tienen un mayor nivel de educación. Estos pacientes consultan múltiples fuentes, pero no conceden una menor confianza a las fuentes tradicionales de información.

The Internet has revolutionized the field of communication and information for patients. According to a survey conducted by the National Statistics Institute of Spain, in 2019, 72% of the population searched for information on health issues on the Internet.1 Universal access to the Internet and the use of smartphones allow patients to easily and instantly access (whether from home, work or even from the public road) an inexhaustible source of information.2

According to data from 2019, at that time there were 450 million Internet users in Latin America and the Caribbean,3 so it is foreseeable that digital information sources (DIS) will end up displacing traditional information media such as television, radio or the written press.4,5

A better clinical evolution, a better quality of life and less damage have been observed in patients who receive sufficient information about their condition and participate in decision-making with their treating medical teams, especially those related to the therapeutic strategies offered.6

On the other hand, some authors have suggested that access to information sources through search engines such as Google (or, as many people colloquially mention, “Dr. Google”) can result in patients arriving over-informed or even “self-diagnosed” to the medical consultation and that confront clinical criteria, undermine the credibility of the treating doctor's management and hinder the processes of diagnosis and treatment.7–9

For this reason, the following study was carried out, which aimed to evaluate if there are characteristics that differentiate patients who consult DIS from those who do not, and if there are differences in the credibility that both groups of patients attribute to the traditional sources of information, to the digital ones and, in particular, to those provided by their medical teams.

Materials and methodsIt was taken a database that was part of a work published in 2022,10 which aimed to analyze the frequency of use, search intention and level of credibility of 12 selected sources of information in rheumatology: information about the disease given by the doctor during medical care in the office, talks to the community by health professionals, scientific associations, patient organizations, other patients with the same disease, family members, friends or neighbors, written press, television, radio, books, Facebook and YouTube.

Briefly, an anonymous survey was conducted during the rheumatological consultation to outpatients over 18 years of age, who had been diagnosed for at least six months. It was decided to carry out the surveys taking advantage of the scheduled appointment, to avoid asking patients to return on another occasion exclusively to complete the survey. There were no other inclusion/exclusion criteria beyond signing the informed consent and answering the survey.

The surveys were conducted by the authors between April 2019 and March 2020. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis (SSc), and spondyloarthritis, including patients with psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, were surveyed.

They were asked if in the last year:

- 1

They had obtained information about their rheumatic disease from any of the 12 sources selected. They were requested to clarify whether they had consulted information about their rheumatic disease from any other source not identified in the survey and, if so, to clarify which source they had consulted.

- 2

Each patient rated the credibility they attributed to the different sources of information, on a scale of 0–10, where 0 is no credibility and 10 is the maximum possible credibility.

- 3

The patients were asked about their search intention, defined as the place where they would like to obtain information about their rheumatic disease if they wanted to do so today.

The patients were divided into two groups, according to whether:

- 1

They had consulted, at least, one DIS (DIS group), which included: Facebook, YouTube and other sources on the Internet (Twitter, Google or other search engines).

- 2

They had only consulted traditional sources of information (non-DIS group), which included: the doctor during the consultation, other patients with the same disease, relatives, neighbors or friends, associations of patients with the same disease, talks to the community by health professionals, scientific associations, written press, radio, television and books.

Demographic data, educational level (1: primary; 2: secondary; 3 tertiary or university), time of evolution of the disease in years, availability of a computer or cell phone with Internet access, participation in social networks and reading of digital written media on the Internet were collected. It was recorded whether the patients had any health coverage, whether they received health benefits from entities financed by contributions and mandatory contributions from workers and employers, whether they were treated in public or private hospitals, and also whether they had been surveyed in health centers in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires or outside it.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of all variables was carried out, with frequency and percentage for categorical variables, while for continuous variables the mean with the standard deviation or the median with the first quartile (Q1) and the third quartile (Q3) were used, as appropriate according to the distribution of the variable. Nominal variables were assessed in two independent groups with the chi-square test. Student's t-test was used to compare means. Medians were compared using Mann-Whitney/Kruskal-Wallis. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed: in the multivariate analysis, “having searched for information in DIS” was considered the outcome variable. A P-value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Epi Info version 7.2.5.0 and the R software (Epi Info™, http://wwwn.cdc.gov/epiinfo/) were used for the statistical analysis.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the bioethics committee and all patients signed informed consent.

ResultsOverall resultsA total of 402 patients, of which 318 (79%) were women and the rest were men were surveyed. There were 207 patients (51%) who had consulted at least one DIS in the previous year (DIS group).

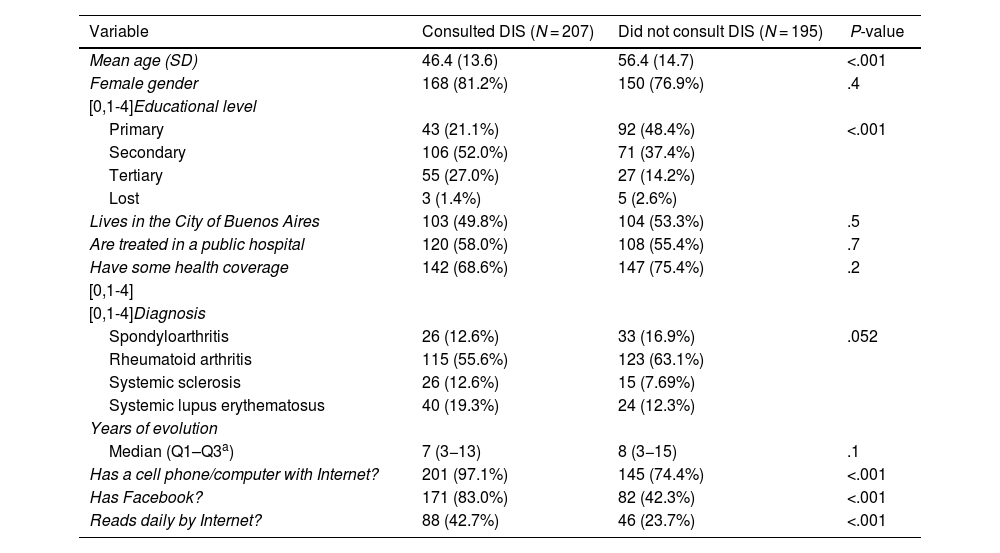

As can be seen in Table 1, the patients who had consulted DIS were younger and had a higher educational level. Patients in the DIS g9*roup had, to a greater extent, a telephone or computer with Internet access, a Facebook page, and read digital written media more frequently.

Characteristics of the patients surveyed according to whether they had consulted digital information sources (DIS) or not.

| Variable | Consulted DIS (N = 207) | Did not consult DIS (N = 195) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 46.4 (13.6) | 56.4 (14.7) | <.001 |

| Female gender | 168 (81.2%) | 150 (76.9%) | .4 |

| [0,1-4]Educational level | |||

| Primary | 43 (21.1%) | 92 (48.4%) | <.001 |

| Secondary | 106 (52.0%) | 71 (37.4%) | |

| Tertiary | 55 (27.0%) | 27 (14.2%) | |

| Lost | 3 (1.4%) | 5 (2.6%) | |

| Lives in the City of Buenos Aires | 103 (49.8%) | 104 (53.3%) | .5 |

| Are treated in a public hospital | 120 (58.0%) | 108 (55.4%) | .7 |

| Have some health coverage | 142 (68.6%) | 147 (75.4%) | .2 |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Diagnosis | |||

| Spondyloarthritis | 26 (12.6%) | 33 (16.9%) | .052 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 115 (55.6%) | 123 (63.1%) | |

| Systemic sclerosis | 26 (12.6%) | 15 (7.69%) | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 40 (19.3%) | 24 (12.3%) | |

| Years of evolution | |||

| Median (Q1–Q3a) | 7 (3−13) | 8 (3−15) | .1 |

| Has a cell phone/computer with Internet? | 201 (97.1%) | 145 (74.4%) | <.001 |

| Has Facebook? | 171 (83.0%) | 82 (42.3%) | <.001 |

| Reads daily by Internet? | 88 (42.7%) | 46 (23.7%) | <.001 |

In general, the number of sources consulted by patients in the DIS group was higher: median of five information sources (Q1–Q3: 3–7) vs. 2 (Q1–Q3: 1–3) in the rest (P < .001).

When the search intention and the level of credibility were assessed, they were also higher in the patients who had consulted DIS: median of 6 (Q1–Q3: 4–9) vs. median of 3 (Q1–Q3: 2–6) in the rest (P < .001).

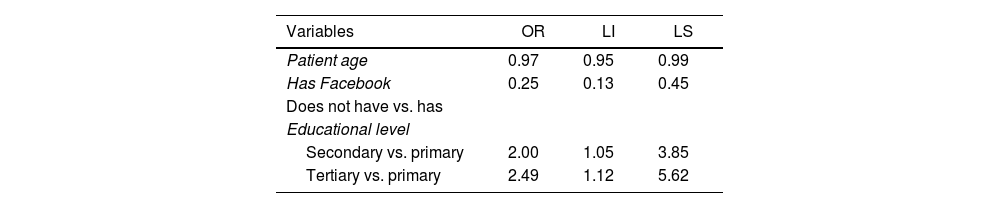

Multivariate analysisThe results of the variables are presented together in Table 2 and it is concluded that the opportunity to make a query in DIS:

- -

Is reduced by 3% as the patient's age increases by one year.

- -

It is higher with a higher educational level: it is twice higher for the patients who had secondary level with respect to those with primary level and 2.5 times higher for the patients of tertiary level, compared with those who had primary education.

- -

It is 75% lower if the patient did not have Facebook.

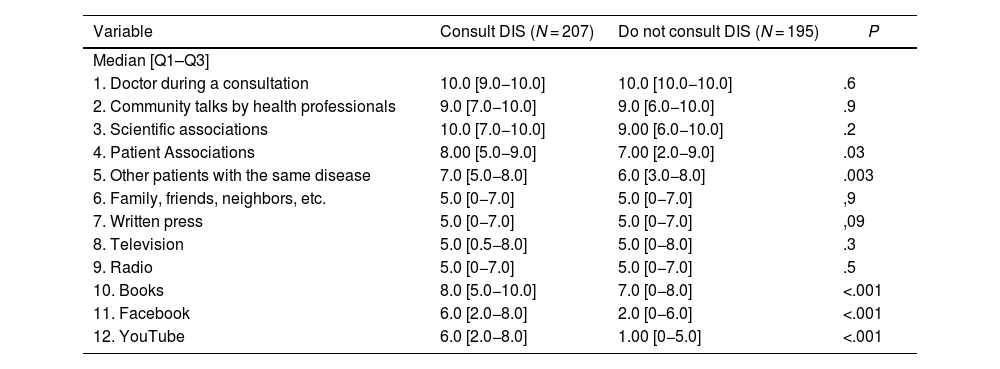

Patients who had consulted DIS attributed greater credibility to Facebook and YouTube than the rest. However, they did not have less credibility than the rest in any of the traditional sources. On the contrary, they had greater credibility in books, in “Other patients with the same disease” and in “Organizations of patients with the same disease” (Table 3). In particular, no differences were observed between the two groups in the level of credibility they attributed to the treating physician or to scientific associations as a source of information.

Level of credibility from 12 selected sources of information, described by respondents, depending on whether they consulted digital sources of information (DIS) or not.

| Variable | Consult DIS (N = 207) | Do not consult DIS (N = 195) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median [Q1–Q3] | |||

| 1. Doctor during a consultation | 10.0 [9.0−10.0] | 10.0 [10.0−10.0] | .6 |

| 2. Community talks by health professionals | 9.0 [7.0−10.0] | 9.0 [6.0−10.0] | .9 |

| 3. Scientific associations | 10.0 [7.0−10.0] | 9.00 [6.0−10.0] | .2 |

| 4. Patient Associations | 8.00 [5.0−9.0] | 7.00 [2.0−9.0] | .03 |

| 5. Other patients with the same disease | 7.0 [5.0−8.0] | 6.0 [3.0−8.0] | .003 |

| 6. Family, friends, neighbors, etc. | 5.0 [0−7.0] | 5.0 [0−7.0] | ,9 |

| 7. Written press | 5.0 [0−7.0] | 5.0 [0−7.0] | ,09 |

| 8. Television | 5.0 [0.5−8.0] | 5.0 [0−8.0] | .3 |

| 9. Radio | 5.0 [0−7.0] | 5.0 [0−7.0] | .5 |

| 10. Books | 8.0 [5.0−10.0] | 7.0 [0−8.0] | <.001 |

| 11. Facebook | 6.0 [2.0−8.0] | 2.0 [0−6.0] | <.001 |

| 12. YouTube | 6.0 [2.0−8.0] | 1.00 [0−5.0] | <.001 |

Q1: first quartile; Q3: third quartile.

In this study it has been observed that the patients who consult DIS correspond to a group of younger people with a higher educational level. Although they have greater confidence in DIS and consult more sources of information regarding their illness than the rest of the people, this does not imply that they feel less confidence in the information provided by the doctor during the consultation or in traditional sources of information.

In a review article published in 2020 on the use of social networks in rheumatology, the authors recognized that the discussion was no longer whether or not to accept the use of DISs, but rather how well doctors would adapt to them.11

According to a publication by the Pan American League of Rheumatology Associations (Panlar) in 2016, 10% of all Internet users worldwide are from Latin America. In addition, Facebook is the social network with more users in the region (more than 1.8 million users), followed by YouTube, which has 1.3 million users.12

Several studies analyzed videos on rheumatic diseases published on YouTube.

In general, an acceptable level of quality and reliability of information has been reported, which is usually higher in videos generated by academic associations or professional institutions. However, published studies indicate that patients should be alerted about the existence on the Internet of misleading information or medical propaganda generated by individuals or for-profit organizations.13–22

In an article published in 2015 regarding the education of patients with RA in Latin America and the Caribbean, it was pointed out that older patients did not have the same ease as younger ones in accessing the Internet and therefore educational materials should be designed according to their needs. In addition, although the publication of educational videos on YouTube was not discouraged, it was suggested the participation of multidisciplinary teams in the preparation of the content.23

An Argentinian study published in 2018, which was carried out with 496 patients with RA, reported that around 20% of patients turned to the Internet as a source of information. As in this work, the authors reported that patients who turned to the Internet had a significantly younger average age.24

In a study conducted with 13,262 social network users, online posts about ankylosing spondylitis were analyzed. Users could be patients or people who provided support or care to individuals who needed assistance for this condition. The majority of topics (60%) focused on discussing the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis, while the remaining topics addressed issues such as the psychological impact, medical literature, and consequences of the disease. It was observed that 80% of users under 49 years of age used social networks and this percentage increased as age decreased.25

Regarding education, in an online survey of more than 400 patients with RA and osteoarthritis, it was found that as the patients' level of education increased, so did their search for information about their medication.26

This study has the following limitations: since the survey was carried out taking advantage of a scheduled consultation, even if it was an anonymous survey, it is possible that there is a bias in the opinion of patients about their treating physician. In addition, although both scientific associations and patient organizations have mixed models that also include digital channels (e.g., Facebook and YouTube), it was decided to analyze them together with other traditional sources.

To carry out this study, patients with conditions that are very common in rheumatology, such as osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, which characteristically affect older patients, were not included.

In this work, patients evaluated 12 sources of information. The systematic analysis of the information contained in each source is left for other scientific productions.

As strengths, this study has allowed the inclusion of more than 400 patients of different ages and educational levels, where more than 85% had a computer or cell phone with Internet access. The patients who answered the survey presented 4 clinical conditions that are very relevant in the specialty, such as RA, psoriatic arthritis, lupus and SSc.

ConclusionsThe fact that a patient seeks information from an DIS does not mean that he/she has less confidence in his or her treating physicians or in traditional sources of information. On the other hand, if scientific information is to be disseminated through DIS, it should be considered that the population that most frequently accesses these sources tends to consult multiple sources, is younger and has a higher educational level.

FundingNone.

The authors would like to thank Professor Ana Insausti for her collaboration in the translation of the abstract and the Clinical Research Unit of the Argentine Society of Rheumatology (Unisar) for their advice on the study.