The editorial committee of the Revista de Contabilidad – Spanish Accounting Review has very kindly invited me to provide a brief presentation for the present issue of the journal, leaving the subject for discussion up to me. In taking this decision, I checked out the information on the ‘ResearchGate’ portal about my scientific production and found that the article entitled ‘Accounting for Intangibles: A Literature Review’, written in collaboration with Manuel García Ayuso and Paloma Sánchez,1 is by far the most read and cited article of all those I have published in international media; it has had 2064 readers and 303 citations [accessed on December 22nd, 2017]. This has led me, even though I am no longer, at this point in my life, as immersed in the research of this subject as I was at the time that paper was published, to prefer this topic over others that might have attracted my attention more recently.

Back in the day, 1998–2010, I was lucky enough to be involved in a series of interlinked European research projects, either aimed at the measurement and reporting of intangibles in the context of business innovation: MERITUM (1989–2001),2 E-KNOW.Net (2001–2003),3 PRIME (2004–2008)4 or else discussing accounting harmonization in Europe and its approach with respect to IFRS: HARMONIA (2000–2003),5 INTACCT (2007–2010).6 My participation in these research projects afforded me multiple contacts and international collaborations, which represented a major stimulus to my research career, giving rise to numerous international publications, but none of these has managed to achieve the level of dissemination reached by the article mentioned. I must, therefore, once more deal with intangibles at the present time.

Emphasizing intangiblesAt the present time, intangible assets are major creators of business value and a source of competitive advantage. Companies are more and more basing their success and survival on innovation and knowledge management and generation. Innovation covers the creation of new products and services, the implementation of new processes, changes in customer management and the ways of working or organizing business management, and the development of human resources, relationships and new markets. For this reason, innovation requires and leads to investment in abilities and in such intangibles as creativity, brand image, intellectual property and patents, i.e. the creation of intellectual capital for businesses.

Knowledge and constant innovation are currently the main factors contributing business value by giving rise to the generation of intangible items on which to base new processes and products, and these intangibles are in turn a source of further knowledge and innovations. In 2015, intangibles, also referred to as ‘intellectual capital’,7 represented 87% of the market capitalization of listed companies forming part of the S&P 500 stock-market index8; trade marks represent a large percentage of these assets, with expenditure on R&D often exceeding the net profits of these companies.

Having said that, and without prejudice to the more recent emergence of such intangibles as corporate reputation and corporate social responsibility (CSR). On the relevance of corporate reputation, suffice here a quote from Warren Buffett: ‘Act with honor and integrity: It takes twenty years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it; if you think about that, you’ll do things differently.’9 With respect to CSR, according to the Edelman 2016 Confidence Barometer, 80% of interviewees stated that a company must contribute to an improvement in the social and economic conditions of the environmental in which it operates.10

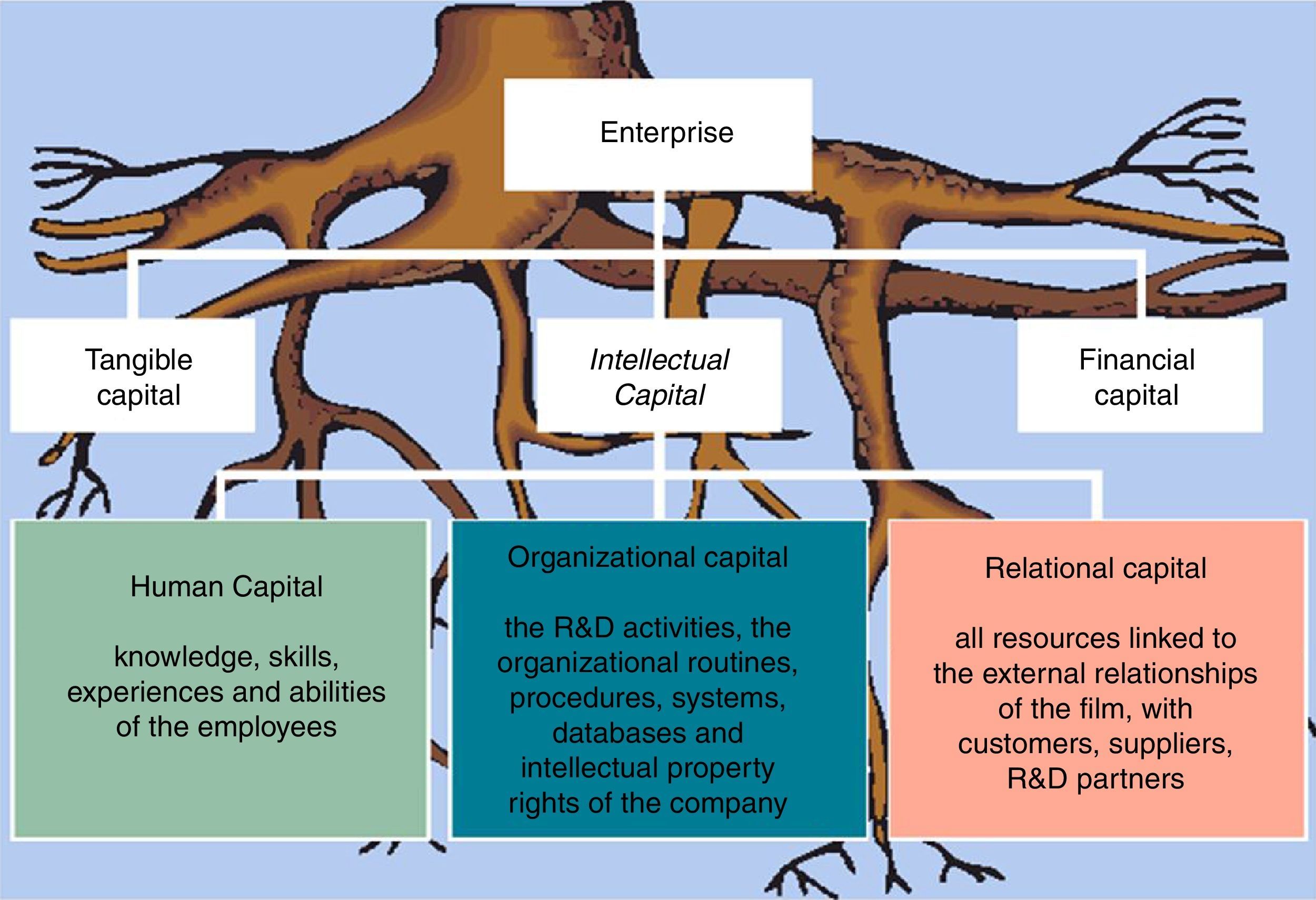

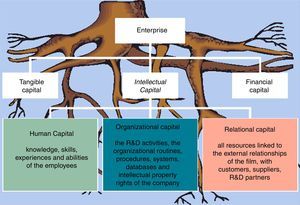

There are several definitions of intellectual capital and its components but it is common for a distinction to be drawn between human capital, organizational capital and relational capital (MERITUM, 2002: 3). Human capital reflects individual abilities, know-how, skills and expertise of a company's employees and executives. Organizational capital is the knowledge ensemble that remains in the company at the end of the day; it includes the company's patents, operating structures, administrative organization and information systems, its installed capacity, reputation and image, as well as its productive efficiency and corporate culture. Finally, relational capital is the set of resources linked the external relationships the company has with its clients, suppliers, shareholders or partners and its surroundings. This network of relationships can be represented as the roots enabling the growth of a tree, now and in future, as shown in the following diagram (Fig. 1).

Intellectual capital therefore refers to the status of relationships, the creation of value or the improvements in the skills and abilities of the people making up the company. These characteristics inherent to intangibles: tacit nature, difficulty for their transmission within the company and blurred ownership limits hinder both the extraction of value from this capital and also its valuation. On occasion, it is not even possible to establish its existence. All this hinders its definition, valuation, measurement, interpretation and management, and hence the communication of relevant information regarding its intangible components for the taking of decisions.

These difficulties, at the same time as posing a challenge, highlight how much remains to be investigated in the vast field represented by intangibles generated by business innovation and at the same time driving this innovation. Before referring expressly, however, to aspects relating to the management and reporting of intangibles, please allow us some brief notes on the main characteristics differentiating these elements from those of a tangible nature (Cañibano, García-Ayuso, & Sánchez, 2000).

Investment in intangible assets is clearly very different from investment in tangible assets. Investing in intangible assets generally entails greater risk and, for this same reason, a higher return is expected from them. As opposed to what happens with tangible assets, intangibles are capable of simultaneous use; by way of example, consider the case of an airline, with restrictions on the capacity of its fleet (tangible) versus the versatility of its booking system (intangible). Whereas tangible assets tend to follow the law of diminishing returns, this does not happen with intangibles because of the cumulative nature of knowledge; intangibles are usually characterized by requiring high sunk costs11 and low incremental costs, as often happens, for instance, in such sectors as the pharmaceutical industry or information and communications technologies. Given their great versatility, the only factor limiting the use of intangibles is the market, something that does not happen with tangible items subject to other kinds of restrictions. Lastly, we must not overlook the immense potential of the networked use of intangibles, with the consequential economies derived from this circumstance.

These inherent characteristics of intangible resources and activities generate differences between the (extensive) economic concept of intellectual capital and the much more limited accounting concept of an intangible asset that is used as the basis for drawing up the third-party financial reporting information that companies have to publish from time to time. It is precisely the existence of intangible assets not recognized for accounting purposes that explains a large part of the well-known discrepancy between market capitalization and the book value of companies. There is a considerable distance between these two values, as has repeatedly been made clear in the specialized literature, particularly in one of the earliest studies of this matter (Lev & Zarovin 1999).

Back to the fray with reporting of intangiblesIn an attempt to classify the successive contributions to the debate on intangibles, some more recent papers (Guthrie et al., 2012; Dumay & Garanina, 2013, Dumay, 2016) have divided this process into the following four phases or stages:

- (1)

During the late 1980s and the 1990s, the various contributions attempted to create a conceptual framework for intellectual capital in order to help visualize these invisible resources and therefore enable them to be measured and ultimately reported. Their methodological foundation lies in “grounded theory”. The most significant authors in this period were Kaplan and Norton (1992), Edvinson (1997) and Stuart (1997).

- (2)

Starting in the early part of this century, we are told (Dumay, 2013:12) that researchers continued to emphasize the measurement and reporting of intangibles, with the MERITUM (2002) Guidelines being considered a ‘seminal’ work. As one of the co-authors, it should like to point out that this texts goes far beyond that content, as these Guidelines devote an entire chapter to managing intellectual capital, and delves more deeply into the concepts of ‘critical intangible’ and ‘commercially exploitable intangible’, both closely linked to business strategies. Other studies also considered relevant are the Danish IC Reporting (Mouritsen et al., 2003) and the European project, InCaS.12

- (3)

Guthrie et al. (2012) pointed out that a new research approach was emerging around that time, based in practice on how businesses used their intellectual capital. This approach not only considers value in monetary terms but also treats other values incorporated into the products and services addressed to clients and other third parties as valuable and important. A transformation is being wrought in research into intellectual capital in pursuit of engagement in the company's internal processes, as already discussed in fact in the MERITUM (2002) Guidelines referenced above.

- (4)

In an attempt to push the envelope further, Dumay (2016) one more redrafted the aims of research into intellectual capital, highlighting that the aim of reporting on intellectual capital is not appropriate; for Dumay, the myth of value creation based on better reporting has not worked and so must be ‘buried’.13 It is necessary to help organizations disclose what previously had been kept secret or was simply unknown. It is not a matter of reporting but revealing, by means other than reports, information that affects intellectual capital, albeit not classified as such.

We have to agree that the emphasis placed on reporting intangibles at the time has failed to achieve its goals, as the reference framework for accounting information has not changed enough to accommodate a more flexible valuation criterion for these, assuming one of the proposals submitted (Lev, Cañibano, & Marr, 2005:42), or to supplement an estimation in this respect via the notes to the accounts. On the other hand, there are indeed new reporting obligations on sustainability and social responsibility, but these too have failed to achieve the mandatory inclusion of information about intangibles.

Is it possible now, with the new EU directive on non-financial information,14 to expect any disclosure of information on intangibles or intellectual capital among non-financial information? At the present time, after its transposition, this directive will be compulsory in Spain for listed companies and other public interest entities. Non-financial reports of this kind could be subjected to verification by an independent professional, similar to the auditor's report accompanying the company's financial statements.

The analysis of intangibles as a management toolRegardless of the foregoing with respect to reporting and in order to emphasize the management vision implied by an analysis of intangibles, not only after 2012 but even earlier as shown in the MERITUM Guidelines (2002), I have included here an extract from a report produced in the now distant 2003 at the request of the Office of the President of Real Madrid football club, in view of the accounting controversy that arose at the time.

A member of the previous Governing Council of that sports entity submitted a complaint to the Spanish accounting authority, ICAC, regarding the accounting treatment given to the revenue derived from the sale of stakes in the “Set of Rights” that we will be referring to below, with the argument that, in the accounting sphere, this revenue was similar to that obtained by television sports broadcasts and that it should therefore accrue over the term of the contract's duration. These are obviously two completely different transactions, with the first implying revenue from the sale of an intangible on the date of the contract, whereas the second refers to the revenue produced and recognized on each of the dates corresponding to the effective provision of the service. This was how it was also understood by the ICAC when it proceeded to dismiss the allegations.

At the start of the 2000–2001 financial year (July 1st, 2000), the Real Madrid football club held certain intangibles that were not recognized for accounting purposes on its balance sheet.

Although there is a long-standing refrain stating that what isn’t recognized for accounting purposes does not exist, the fact of the matter is that the emergence of the knowledge-based economy has proved the existence of considerable intangible elements that are critical for the creation of value in a company; they not only exist but are decisive for the generation of the company's future profits.

The mere existence of such intangible elements does not generate value; it is necessary for them to be identified by the management, especially those of a critical nature, i.e. those directly associated with the company's strategic goals, and for the necessary means to be provided to turn these into commercially exploitable intangible assets.

Following the elections held on June 16th, 2000, a new Governing Council led by Florentino Pérez took over at Real Madrid and, after examining the practices applied by certain leading international teams, identified the club's brand and image as well as the image of Real Madrid's players as critical intangibles and then implemented the means for turning these into commercially exploitable intangible assets, adapting the Club's internal organization to the new strategic goal established, and seeking co-operation agreements with other entities with experience in the promotional business to be developed.

The so-called “Set of Rights” (corresponding to Merchandizing, Club Image and Players’ Images, Internet and Distribution) is simply an accumulation of the commercially exploitable intangibles we have been referring to, as they arise as a consequence of the strategic decisions adopted by the new Governing Council of Real Madrid and the subsequent actions taken. In other words, it is a new business to be developed, with expectations of future profits that have gradually materialized more and more over time.

The co-operative agreement entered into with “Accionariado y Gestión” (in the Caja Madrid Group) and “Sogecable” represented the sale by Real Madrid of percentage stakes of 20% and 10%, respectively, in the preceding intangible assets for a total amount of 19.5 billion pesetas. Given the accounting recognition of these intangibles at the time, most of the costs originated by the same were charged to expenses; as a result, the amount on the balance sheet was small, so the difference between the amount received and the amount recorded on the balance sheet came to 19.3 billion pesetas, which were posted to accounts as the extraordinary profit from the sale of intangible fixed assets, as prescribed by the General Table of Accounts in force.

The aforesaid stakes gave their respective registered holders the right to participate in the profits derived from exploitation of the business mentioned, with the purchasers assuming all the risks inherent to the same, identical to those assumed by Real Madrid with its remaining 70% stake, which it continues to hold. This is therefore a definitive sale that is not conditional on any variation in the revenue that might arise in future in the exploitation of the business indicated.

On the other hand, it should be noted that the corresponding amounts were collected practically immediately, with all the deferred sums collected in full during 2001.

In view of these circumstances: definitive transactions, total transfer of the risk and collection of the price, it is appropriate to recognize this revenue for accounting purposes as income in the financial year in which the stakes in the business associated with the commercial exploitation of the intangibles in question were sold for the corresponding amount.

Term for the sale of intangible assetsThe physical, human and financial resources compete among possible alternative uses within a company, i.e. they are rival with each other. If an aircraft and its corresponding crew is assigned to a particular route, it cannot simultaneously cover another route, thus giving rise to a missed opportunity. On the other hand, intangible assets may be capable of being used simultaneously; an airline's booking system (organizational capital) can handle an unlimited number of clients, and no opportunities are missed.

This characteristic of intangible assets, namely their possible simultaneous and repetitive use without diminishing their usefulness, explains why companies consider these to be major value generators. Their returns are only limited by the size of the market, not by the scarcity of the asset in question.

This characteristic is important when considering the sale of an asset of this nature because these items do not have diminishing returns and a predetermined working life, as would be the case of a transportation item, a machine or a building, but rather they are elements than can have more value the more they are used, which makes it advisable to establish a limited period, in view of the price agreed and the level of return expected, in line with the corresponding business risk.

The sale of a stake in the business consisting in the commercial exploitation of certain intangible assets of Real Madrid (Brand and the image of the Club and its players) must logically contemplate a limited term because the asset being sold, involving as it does an intangible, will continue to exist in the long term but its value can change radically depending on the use being made of it. If this use intensifies, the greater expectations of future profits will increase the value of the item, whereas it will have the opposite effect if it ceases to be used. The establishment of a term is logical for both parties: for the vendor, because it will continue to preserve its long-term potential to generate profits, and for the purchaser because the term established enables it to recover its investment together with the corresponding business return.

We are talking here of selling the use of an entity's image, so it is difficult to contemplate the possibility of a sale of such an asset class in perpetuity, even in the scenario where the Governing Council had the power to adopt irreversible decisions on the Club's distinctive hallmarks. Prudence would make it advisable to sell only that part of the image whose value can be estimated over a reasonable period of time. This is precisely what Real Madrid did, by initially estimating a term of eleven years, with the possibility of an additional extension for a further five years.

Following the sales transactions involving commercially exploitable intangibles undertaken in the 2000–2001 financial year, there was another transaction in the 2002–2003 financial year, which reduced the stake held by Accionariado y Gestión (in the Caja Madrid Group) by 7.5%, a stake that it had passed, via Real Madrid, to Media Cam Production Audiovisual, S.L. Both companies, “Accionariado y Gestión” and “Media Cam” saw their exploitation term extended to thirteen years, while at the same time accepting clauses that enabled them to reduce or extend the term when the profitability achieved exceeded certain percentages or when an agreed minimum percentage was not achieved. In this way, by combining the term and the return, Real Madrid reserved for itself any superprofits that might arise from the commercial exploitation of the said intangibles, without prejudice to stimulating its investor through the extension of the term to enable it to achieve a particular level of profitability.1515 This policy of linking term and return has been applied in the commercial exploitation of some other intangibles, such as, for example, administrative concessions granted by the State for the operation of motorways.

These latter considerations do not alter the essence of the commercially exploitable intangibles as described above and whose characteristics have been highlighted, nor do they alter the accounting treatment applied to the sales transactions for stakes in the business for their commercial exploitation.

Accounting of the tax effect corresponding to the sales transaction for the stakes in intangible assetsThe intangibles sold were generated by the Club over a period of time (we are talking about its brand and its image), although the actions needed to turn them into commercially exploitable assets had not been taken; the costs originated by the same had been posted to accounts in their day, although, in view of the generally accepted criteria in place in this regard, the amounts recorded on the balance sheet were quite scant, with the remainder forming part of the successive Profit and Loss Statements.

From an accounting perspective, it is appropriate to recognize the corresponding tax impact, consisting in posting 25% of the 19.3 billion pesetas the amount of the sale came to, namely 4.825 billion pesetas, as a liability for deferred taxes, as reflected in Real Madrid's Annual Accounts closed as of June 30th, 2001.

In conclusionIn accordance with the conceptual reasoning applied as set out above, the accounting criteria applied by Real Madrid in its Annual Accounts closed as of June 30th, 2001, with regard to the sale of the “Set of Rights” or, in our words, “commercially exploitable intangibles”, are compliant with Accounting Principles and Rules Generally Applied in Spain, as was accredited by the auditors of the said Annual Accounts.

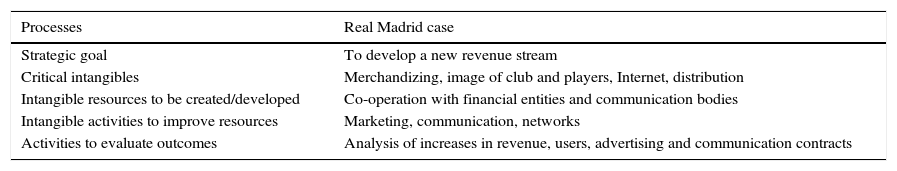

We consider the preceding case to be a good exponent of the analysis of intangibles from a strategic standpoint, aimed at the development of a new revenue stream for the sports club. First it identified the critical intangibles for achieving its goal sand then, by making them ‘commercially exploitable’ through the endowment of additional resources based on co-operation with other companies and the performance of activities for their improvement and subsequent valuation.

Replicating the same scheme for the process of identifying resources and intangible activities as in the MERITUM Guidelines (4.1 Figure 3) to the preceding Real Madrid case, we would obtain the following diagram:

| Processes | Real Madrid case |

|---|---|

| Strategic goal | To develop a new revenue stream |

| Critical intangibles | Merchandizing, image of club and players, Internet, distribution |

| Intangible resources to be created/developed | Co-operation with financial entities and communication bodies |

| Intangible activities to improve resources | Marketing, communication, networks |

| Activities to evaluate outcomes | Analysis of increases in revenue, users, advertising and communication contracts |

This focus of the analysis of intangibles on the company's management, taking into account its strategic aim, has been studied by an author highly characterized in this field, namely Baruch Lev (Lev & Gu, 2016), after highlighting the constant deterioration in the usefulness and relevance of financial reporting for investment decisions over the last half century, a process that has gained in momentum in recent decades. Financial reporting no longer reflects the factors that create value and give businesses a substantive competitive advantage.

The following are pointed out as examples of types of information that would be important for investors, quite apart from that provided through financial reporting:

- -

The company's strategy, i.e. how it executes its business model.

- -

Major indicators, such as the number of new clients.

- -

In the case of vehicle insurance companies, the frequency of accidents and their severity.

- -

Among pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, the results of their clinical trials.

- -

Among oil and gas businesses, confirmed variations in known reserves.

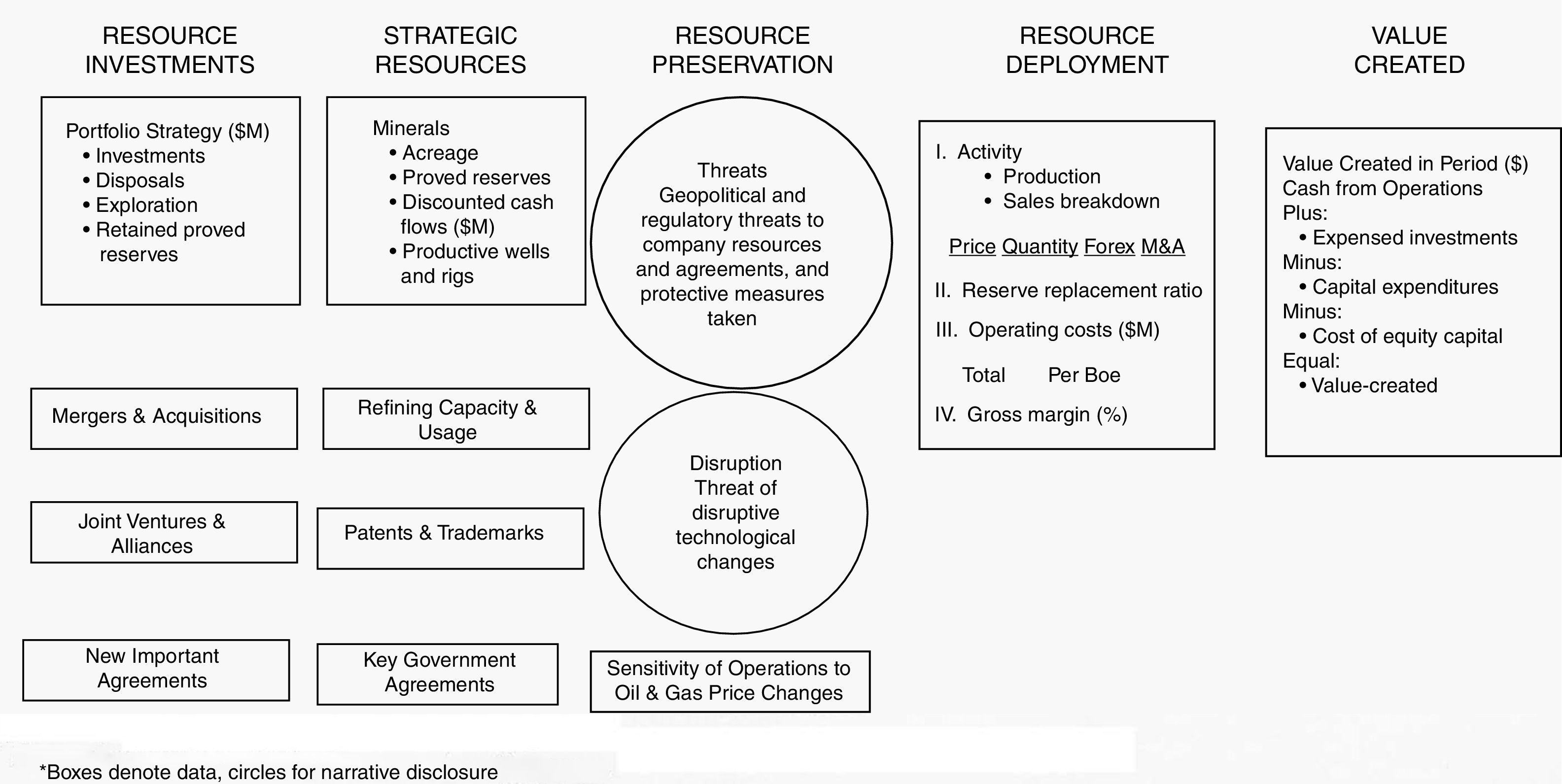

These circumstances led to the proposal of a new complete information paradigm for investors and executives in the 21st century: ‘The report on strategic resources and their consequences’. The resources the report is to provide are those of strategic value in modern companies, such as patents, trademarks, technology, natural resources, operating licences, clients, business platforms and the company's relationships with third parties. These basically concern intangible concepts included within intellectual capital.

In order to depict these ideas in a summarized form, the aforesaid authors present a report template in the work cited and they apply it to the industries mentioned above. We reproduce below the report on strategic resources and their consequences with respect to oil & gas companies (Fig. 2).

Strategic resources and their consequences with respect to oil & gas companies.

It is worth noting the effort made to compile a suite of highly relevant information in the model presented; without doubt, this has influenced (and will continue to influence) the information disclosed in practice by companies in the sector indicated. For our part, we have been able to confirm that Repsol now distributes information of this type through some of the reports accompanying its Annual Accounts and Management Report, such as the report on hydrocarbon exploration and production activities, including details on investments and results, strategic resources, such as proven reserves, mining rights, exploring activities and others.

In shortWherever traditional financial and accounting information cannot reach, other kinds of information, starting from an analysis of intangibles, may facilitate the disclosure of the critical elements creating value. Call it a report on strategic resources or give it some other name, but publish it. As was said at the beginning, we are immersed in an economy of the intangible; today more than ever before, intangibles are important creators of business value and a source of competitive advantage. Let us never lose sight of that.

Professor Emeritus.

Published in: Journal of Accounting Literature, vol. 19, 2000, pp. 102-130. Reprinted in: Readings on Intangibles and Intellectual Capital, Cañibano, L. and P. Sánchez (Editors), AECA, Madrid 2004.

Measuring Intangibles To Understand and Improve Innovation Management.

A European Research Arena on Intangibles.

Policies for Research and Innovation in the move toward the European Research Area.

Accounting Harmonisation and Standardization in Europe: Enforcement, Comparability and Capital Market Effects.

The European IFRS Revolution: Compliance, Consequences and Policy Lessons.

This has been highlighted in the MERITUM Guidelines: 3. Conceptual framework.

http://www.kpmgblogs.es/el-valor-de-la-reputacion-y-los-intangibles-en-el-contexto-economico-actual/.

https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/267618.

http://www.pacificlatam.com/investigaciones/barometro-de-la-confianza-2016/.

Overheads caused by past decisions.

http://www.incas-europe.org/home/index.html.

Then I declared IC reporting dead and flashed up on the screen a tombstone with the epitaph ‘Intellectual Capital Reporting: 1994-2012’.

Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups.

This policy of linking term and return has been applied in the commercial exploitation of some other intangibles, such as, for example, administrative concessions granted by the State for the operation of motorways.