The 2010 Green Paper on Audit Policy by the European Commission has explicitly questioned the sufficiency of audit rotation rules established by European Union Members to guarantee auditor independence. In addition, the Paper clearly states that more research is needed regarding the effects of long audit tenures on independence. In this article, we have replicated the research by Ruiz-Barbadillo, Gómez-Aguilar, and Biedma (2005) about the effects of audit firm tenure on independence with more updated data. However, unlike them, we have performed panel data estimations instead of pooled regression. Our approach allows for a better control of individual unobserved heterogeneity, thus reducing potential problems caused by omitted variable bias. While Ruiz-Barbadillo et al. reported an unexpected positive effect of tenure on the likelihood of audit qualifications, we do not show any significant effect of tenure on the opinion of the audit report. Our results are robust to various sensitivity analyses.

El Libro Verde sobre Política de Auditoría elaborado por la Comisión Europea en 2010ha puesto en duda la suficiencia del marco regulatorio actual de la auditoría vigente en la Unión Europea para garantizar adecuadamente la independencia del auditor. Además, el documento reconoce explícitamente la necesidad de más investigación sobre los efectos en la independencia del auditor de relaciones de auditoría que se perpetúan en el tiempo. En este artículo, hemos replicado, con datos más actuales, la investigación de Ruiz-Barbadillo et al. Sin embargo, a diferencia de ellos, hemos utilizado un enfoque de datos de panel en lugar de una regresión agrupada. Nuestra aproximación permite controlar mejor los problemas derivados de la heterogeneidad no observada, reduciendo los problemas de sesgo debido a la omisión de variables. Ruiz-Barbadillo et al. obtuvieron el resultado inesperado que a mayor número de años auditados por un mismo auditor más probable era que el informe de auditoría presentara salvedades. Nuestros resultados, por el contrario, no muestran ningún efecto significativo de la duración de la relación con el auditor en la opinión del informe de auditoría. Los resultados obtenidos son robustos a los análisis de sensibilidad que se han realizado.

The growing importance of corporate governance matters for researchers and policy makers, particularly after the dot-com bubble and more recently the contemporaneous financial crisis, has motivated a large body of research on the quality of financial statements. The proliferation of corporate scandals as Enron, WorldCom, Parmalat and Lehman Brothers have posed serious concerns about the reliability of financial statements, since in none of these cases they showed the real situation of the firm.

The external auditor is the key figure to guarantee the quality of financial statements, and thus its role is crucial in the corporate governance scheme. When these statements have an unqualified opinion, participants in the financial markets assume they show the current situation of the firm. Nevertheless, the external auditor faces a conflict of interests regarding the relationship with the audited company that may undermine its credibility when judging its clients’ financial statements. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), passed largely as a reaction to corporate financial scandals of the dot-com era, attempted to improve the quality of financial statements of public companies in the U.S. Among other issues, the SOX included some provisions to strengthen auditor independence. With the same aim, corporate governance codes approved in numerous countries worldwide have included recommendations to guarantee auditor independence.

The length of auditor-client relationships constitutes a major issue in the auditor conflict of interest, because long relationships may cause auditor complacency about management decisions regarding the firm's financial statements. Following this view, the mandatory rotation of external auditors has long been suggested to improve independence. With this aim, the SOX required a study about the potential effects of imposing mandatory rotation. Although the results of the study did not support that auditor rotation increased the quality of financial reports, and therefore, it did not recommend mandatory rotation (Myers, Myers, & Omer, 2003), regulators finally established that lead audit partners and concurring partners could not perform audit services for the same client for more than five consecutive fiscal years. In addition, they also required a minimum five-year time-out period before a partner might return to audit a client. Similarly to the situation in the U.S., mandatory rotation of the audit partner is nowadays required in many countries.

The Green Paper on Audit Policy, (EC, 2010) by the European Commission, explicitly questions the sufficiency of the actual regulatory framework to guarantee auditor independence. The Paper also encourages additional research about the effects of long audit tenures on independence. In this line, the main motivation of this article is to provide new and updated evidence about the effects of audit tenure on independence. Besides, available research for low litigation risk countries following our approach is not only scarce (Ruiz-Barbadillo, Gómez-Aguilar, & Biedma, 2005; Vanstraelen, 2000) but also provides conflicting results. It should also be noted that both articles analyze the audit sector before the fall of Arthur-Andersen and the enforcement of the SOX. During the last decade, not only the audit sector has been subjected to important regulatory changes, but also, litigation risk seems to have increased even in low litigation risk countries. Therefore, as posed among others authors by Fargher and Jiang (2008) and Feldmann and Read (2010), results reported by previous research need to be updated.

This paper makes several contributions to the literature. Firstly and most importantly, the methodology we propose is robust compared with both Vanstraelen (2000) and Ruiz-Barbadillo et al. (2005) (hereafter RBGB). Despite the panel structure of their data, neither Vanstraelen (2000) nor RBGB used a panel data approach to undertake the analyses. Both papers performed a pooled logistic regression, although they did not mention any test on a likely autocorrelation pattern in their data. The main advantage of panel data estimation over pooled regression is that it allows controlling for individual unobserved heterogeneity. Since unobserved heterogeneity is the main problem in non-experimental research, this advantage becomes particularly useful. In the specific case of the investigation of audit qualifications, given the generally low explanatory power of the proposed models, there is a serious potential for an omitted variable bias, due to unobserved heterogeneity. In addition, unlike both Vanstraelen (2000) and RBGB, significance tests have been performed with robust standard errors. This issue becomes important because, due to the panel structure of the data, the error term will not be independent and identically distributed. Consequently, results reported by Vanstraelen (2000) and RBGB might suffer from methodological pitfalls. Secondly, we report new evidence about the effects of tenure on audit qualifications which do not support available evidence for the Spanish market. Unlike RBGB, reporting an unexpected strength of independence associated to longer tenures, we do not find a significant effect of tenure on independence. Finally, unlike both Vanstraelen (2000) and RBGB, which did not check the robustness of the reported results, our results are robust to various sensitivity analyses.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In section “Audit regulation in Spain”, we outline the regulation of the auditor–client relationship in Spain. In section “Review of the literature” we review previous research. In section “Research design”, we develop our model and explain the dataset. In section “Results” are discussed and section “Sensitivity analyses” are presented in section six. Finally, in section “Conclusion”, we summarize the main conclusions.

Audit regulation in SpainThe market for audit services in Spain started with the implementation of the 8th Directive on Company Law. With the main goal of increasing the reliability of the company's financial statements the Spanish Audit Law was enforced in 1988. The Law established the obligation for companies above a certain size to appoint an external auditor to issue a report about the company's financial statements. A change in the legislation in 1997 increased the minimum size for a company to be obliged to audit financial statements, and reduced approximately by a 20% the number of companies subject to audit (Garcıa-Benau, Ruiz-Barbadillo, Humphrey, & Husaini, 1999).

To safeguard auditor independence, the Spanish Audit Law established a set of criteria to regulate the auditor–client relationship. Accordingly, a multi-year contract was established with a length ranging between three and nine years. In addition, independently of the length of the initial contract, the re-election of the audit firm was not allowed. The imposition of a limit in the number of years a company could be audited by the same firm was equivalent to establish a mandatory auditor rotation rule. Nevertheless, both, the limit on the maximum number of years to be audited by the same firm, and the prohibition to renew the audit contract were abolished after a legal reform in 1995. Afterwards, auditors would be contracted for an initial period ranging between three and nine years, but after the expiration of the initial contract the company could renew the contract with the auditor on a yearly basis. A consensus exists that Spanish legislation has not been particularly strict in specifying safeguards to strengthen auditor independence (Gonzalo, 1995; Paz-Ares, 1996; Ruiz-Barbadillo, Gómez-Aguilar, De Fuentes-Barberá, & García-Benau, 2004). Although, from a legal point of view a company could break its audit contract only if a ‘just cause’ exists, given that the Law did not clarify what this just cause could be, a company could hire and fire its auditor without any time limitation (Gomez Aguilar & Ruiz-Barbadillo, 2000).

Similarly to the SOX in the U.S., the Spanish Financial Law was enforced in 2002 as a reaction to corporate financial scandals. During the process of approving the Law, an amendment was included containing the mandatory rotation of the audit firm every twelve years. According to this amendment, the external auditor would be hired for an initial period of three years and could be renewed for periods of three years, with a maximum of twelve years. After the expiration of this term, the change of the audit firm would be mandatory, and a minimum three-year period was required to re-hire the audit firm. This amendment elicited strong criticism from the auditing profession (Ruiz-Barbadillo, Gómez-Aguilar, & Carrera, 2006), which finally led to its withdrawal. At the end of the process, mandatory rotation was limited to change the audit team but not the audit firm.

Following the revised 8th Directive, the 27 member states of the European Union were required to adapt their national law systems. One important feature of this Directive was to establish audit partner rotation, although each State Member could voluntarily fix the maximum length of the auditor-client relationship. Therefore, in 2010 a new Spanish Audit Law was enforced establishing, among other issues, the mandatory rotation of the leading audit partner after seven years. In addition, a minimum two-year period is required for the re-auditing of the same firm. This reform, however, will not affect our results, since our research period ends in 2009.

Review of the literatureThe effects of tenure on auditor independence have been mostly addressed through the issuance of going-concern audit qualifications to financially stressed firms. Only Levinthal and Fichman (1988) for the U.S. and Vanstraelen (2000) and RBGB for Belgium and Spain, respectively, have included in the analysis all types of firms and audit qualifications. Although most evidence does not support a loss of independence with tenure, some evidence to the contrary also exists. While most authors agree that audit qualifications are less likely during the earlier years of engagement, they provide contradictory results about the relationship between tenure and audit qualifications after the initial period. Louwers (1998) and Carcello and Neal (2000), with samples of U.S. companies, did not support a loss of independence with tenure. Vanstraelen (2002) and Knechel and Vanstraelen (2007) reached a similar conclusion regarding the Belgian audit market. Both articles reported that the auditor's going-concern opinion did not appear to be significantly influenced by tenure. Knechel and Vanstraelen (2007) also observed that type I errors, defined as issuing a going-concern opinion to a company which did not file bankruptcy in the following year, appeared to be lower when tenure was longer. However, recent research available for the U.S. has provided contradictory results. While Lim and Tan (2010) reported a positive effect of tenure on the propensity to issue going-concern opinions to financially distressed firms, Gul, Basioudis, and Ng (2011) documented a negative effect.

The analyses carried out by Levinthal and Fichman (1988) for the U.S. and Vanstraelen (2000) for Belgium represented two exceptions in the literature, since they did not limit to financially stressed companies or to going-concern opinions. Both articles concluded that long-term auditor–client relationships significantly increased the likelihood of unqualified audit reports. In addition, both papers agreed that auditors were more willing to issue unqualified reports in the first two years of engagement (the so-called ‘honeymoon period’ in the auditor–client relationship). Conversely, RBGB reported a positive and statistically significant effect of tenure on audit qualifications in Spain. The authors found this result surprising given the institutional characteristics of the Spanish audit market, most importantly the low risk of litigation. However, they considered that it could indicate that auditors were less willing to issue qualified reports during the initial period of engagement because they were more economically dependent of the client. Besides, this result did not support some other research in the Spanish market, which has analyzed the issuance of going-concern audit qualifications to financially distressed companies. Ruiz-Barbadillo et al. (2004) did not observe a significant effect of tenure on the likelihood of audit qualifications. Similarly, Ruiz-Barbadillo et al. (2006), following a panel data approach, concluded that long tenures did not affect audit qualifications, and, as Vanstraelen (2000), that short tenures made audit qualifications less likely. Finally, although the main interest in Jara and López (2007) research was not the implications of tenure on auditor independence, they did not find a significant effect of tenure on the likelihood of qualified reports. The loss of independence associated to tenure reported by Vanstraelen (2000) in Belgium is explained by the low litigation risk profile of the Belgian audit market. However, the strength of independence in longer tenures reported by RBGB is difficult to explain in terms of, either the litigation risk of the Spanish market, or results reported by related research for the Spanish market.

Research designModelTenure has potentially contradictory effects on audit quality as shown by DeAngelo's (1981) classical definition of audit quality as the joint probability an auditor will both detect (competence) and report (independence) material misstatements. The opposite effects of tenure on competence and independence could cause contradictory effects on the likelihood of audit qualifications. However, following previous research we have measured independence through the auditors’ propensity to issue a qualified report.

Accordingly, the research question states:

Does the likelihood of qualified audit reports decrease with tenure?

The issuance of qualified opinions will be influenced by the auditor's perceived consequences in the economic trade-off between the expected cost of the potential loss of a client, on the one hand, and the probability of being exposed to third-party lawsuits and loss of reputation, on the other. Available evidence indicates that the probability of switching the audit firm increases after a qualified report (e.g., Chow & Rice, 1982 and Krishnan, 1994 for the U.S.; Craswell, 1988 for Australia). Besides, Krishnan and Krishnan (1996) and more recently Fargher and Jiang (2008) have supported litigation risk as a major determinant of the auditor's opinion in the U.S. Therefore, in high litigation risk countries, where reputation is of most importance for the audit firm, auditors could be less willing to impair independence compared with the situation in low litigation risk countries. Although litigation risk might have increased in the Spanish market during the last decade, as suggested by the stronger supervisory role of the ICAC (Instituto de Contabilidad y Auditoría de Cuentas) and by the increase in the number of sanctions to auditors, Spain is still considered as a low litigation risk country. Accordingly, the following hypothesis has been stated:Hypothesis The likelihood of qualified reports should be lower in lengthy auditor–client relationships.

For the purposes of this research, audit reports with adverse opinion or disclaimer of opinion are considered qualified reports.

We have used a logistic model to address the effects of tenure on the likelihood of audit qualifications. The dependent binary variable is the auditor's opinion, coded 1 in case of a qualified opinion, adverse opinion or disclaimer of opinion, and coded 0 in case of an unqualified opinion. Our experimental variable is the number of consecutive years a company has been audited by the same firm. Similarly to RBGB, control variables include: the existence of losses; the level of inventories; an indicator of the solvency of the firm; the level of accruals; the size of the audited firm; and the type of audit firm. Unlike RBGB, given the panel structure of our dataset, we have performed a panel data logistic estimation.

Accordingly, we propose the following model:

where:OPINION is a binary variable indicating whether the audit report is unqualified or qualified.

PER is a binary variable with value of 1 if the company's net profit on year t is negative and 0 otherwise. EXTA is computed as the firm's inventories divided by total assets at the end of the year.

FRAC is an indicator of the probability of bankruptcy, as measured by Zmijewski (1984), with weights determined according to Carcello, Hermanson, and Huss (1995).

CCTA is computed as the ratio of working capital to total assets, as an indicator of the level of accruals.

TA is the natural log of the firm's total assets at the end of the year, as a proxy for size.

NM is a binary variable with value of 1 if the company is audited by a non-Big 4 audit firm and 0 otherwise.

TEN indicates the length of the auditor-client relationship. It has been measured as the number of consecutive years the company has been audited by the same firm (TENURE). Alternatively, we have included two dichotomous variables: TENURE<3 is defined as one for those observations with less than three years of tenure and zero otherwise; similarly, TENURE>9 is one for those observations in which tenure is 10 years or more, and zero otherwise.

The discussion of the expected effects of control variables on the probability of qualified reports is based on RBGB. Companies experiencing losses will face a higher probability of receiving a qualified report. Thus, a positive coefficient is expected for PER. The explanation would be that firms having losses will be more likely to involve themselves in earnings management activities (e.g., Defond and Jiambalvo, 1993; Firth, 2002), thus making audit qualifications more likely. The auditing of inventories may represent serious difficulties because it involves two audit assertions: valuation and completeness (McDaniel, 1990). Consequently, as posed by Simunic (1980), audit fees were higher for those firms with relatively large amounts of inventories. In addition, audit errors (Firth, 2002) and lawsuits against auditors (St. Pierre and Anderson, 1984) are frequently caused by inventories. Therefore, we expect a positive coefficient associated to EXTA. FRAC measures the probability of bankruptcy based on Zmijewski (1984), where higher values indicates a higher probability of bankruptcy. Similarly to the predicted effect for PER, previous research (e.g., Kluger & Shields, 1991) supports that financially stressed companies will be more likely to participate in earnings management activities, thus making qualified opinions more likely. Accordingly, we expect a positive coefficient associated to FRAC. Regarding variable CCTA, although RBGB explicitly recognized the limitations of working capital divided by total assets as a measure of earnings management, they included this variable as a proxy of discretionary accruals. Following RBGB we expect a positive coefficient associated to CCTA. Following previous research (e.g., Krishnan, 1994; Lennox, 2000), the likelihood of audit qualifications is higher for small than for big companies. Such effect is usually explained in terms of the higher costs for the audit firm of losing large clients. Thus we expect a negative coefficient associated to TA. Finally, previous research has shown that the opinion of the audit report depends on the characteristics of the incumbent auditor. Accordingly, Big 4 auditors show an incentive to provide higher quality audits consistent with their brand name reputation (Khurana & Raman, 2004), and thus are expected to show a higher propensity to issue qualified reports (e.g., Dopuch & Simunic, 1982; Carey & Simnett, 2006). Therefore, we expect a positive coefficient for variable NM.

Sample and datasetOur sample is formed by the companies quoted in the Spanish Stock Exchange (SIBE market) during the research period: 2001–2009. Data regarding independent variables in the model has been provided by Thomson Reuters Knowledge, while information about the nature of audit reports has been obtained from the Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores (CNMV). Financial information has been taken from consolidated accounts. The year 1990 is the first year available for our experimental variable TEN. Since control variables in our model include liquidity and debt ratios, similarly to previous research, banks and financial companies have been removed from the sample. After removing all companies which have not been listed throughout the entire research period, we have arrived at a total of 83 companies and, given the nine-year period, 747 firm-year observations. Nevertheless, in 30 cases information about at least one variable included in the analysis was not available. Consequently, our dataset has been finally formed by 717 firm-year observations. In this research, we have examined 717 audit reports, 605 of them unqualified, and 112 with a qualified opinion. Therefore, qualified audit reports represent 16% of total reports examined, similar to the 15% reported by RBGB.

In 2002, after the Enron scandal, the Spanish branch of Arthur Andersen merged with Deloitte. For the purposes of this research, we have considered that all companies audited by Arthur Andersen in 2001 and then by Deloitte in 2002 have not changed the audit firm. In our view, this merge will not affect our results, because in practically all cases the audit partner did not change in 2002. Therefore, the potential threats for independence persist.

In Table 1, we show the 717 reports classified by year and type of auditor opinion. As seen by the table, the percentage of qualified reports has ranged between a maximum of 23% in year 2001 and a minimum of 10% in year 2006. In RBGB these percentages are 19 and 12, respectively.

Classification of audit reports by year and auditor opinion.

| Year | Unqualified reports | Qualified reports | Total |

| 2001 | 56 (77%) | 17 (23%) | 73 |

| 2002 | 65 (82%) | 14 (18%) | 79 |

| 2003 | 69 (84%) | 13 (16%) | 82 |

| 2004 | 69 (84%) | 13 (16%) | 82 |

| 2005 | 71 (87%) | 11 (13%) | 82 |

| 2006 | 73 (90%) | 8 (10%) | 81 |

| 2007 | 71 (89%) | 9 (11%) | 80 |

| 2008 | 65 (81%) | 15 (19%) | 80 |

| 2009 | 66 (85%) | 12 (15%) | 78 |

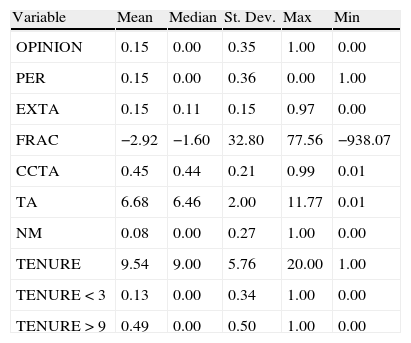

Table 2 shows some descriptive statistics about the independent variables used in the multivariate logistic regression. Focusing on TENURE, the average audit tenure in our sample is almost 10 years, with a maximum of 20 years. Further, while only 13% of cases show firm-audit relationships of two years or less (TENURE<3), in 49% of cases it is 10 years or more (TENURE>9). RBGB reported an average tenure of seven years with a maximum of 11 years. These figures are comparable because both papers, RBGB and our work, use 1990 as the first year available for tenure. Therefore, we could conclude that audit tenures experienced a considerable increase in the past decade. Our sample shows a strong concentration of the audit market by Big4 auditors, representing 92% of the total reports, in line with the figures reported by CNMV (2009) (95 and 96% in 2008 and 2009, respectively). This value is considerably higher compared to the 60% reported by RBGB.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Mean | Median | St. Dev. | Max | Min |

| OPINION | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| PER | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| EXTA | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.97 | 0.00 |

| FRAC | −2.92 | −1.60 | 32.80 | 77.56 | −938.07 |

| CCTA | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.99 | 0.01 |

| TA | 6.68 | 6.46 | 2.00 | 11.77 | 0.01 |

| NM | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| TENURE | 9.54 | 9.00 | 5.76 | 20.00 | 1.00 |

| TENURE<3 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| TENURE>9 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

Variable definitions:

OPINION is a binary variable indicating whether the audit report is unqualified (score 0) or qualified, adverse or disclaimer (score 1).

PER is a binary variable with score 1 if the company's net profit on year t is negative and 0 otherwise.

EXTA is computed as the firm's inventories divided by total assets at the end of the year.

FRAC is an indicator of the probability of bankruptcy, as measured by Zmijewski (1984).

CCTA is computed as the ratio of working capital to total assets, as an indicator of level of accruals.

TA is the natural log of the firm's total assets at the end of the year, as a proxy for size.

NM is a binary variable with score 1 if the company is audited by a non-Big 4 audit firm and 0 otherwise.

TENURE is the number of consecutive years the company has been audited by the same firm.

TENURE<3 is a binary variable with score 1 if tenure is two years or less and 0 otherwise.

TENURE>9 is a binary variable with score 1 if tenure is ten years or more and 0 otherwise.

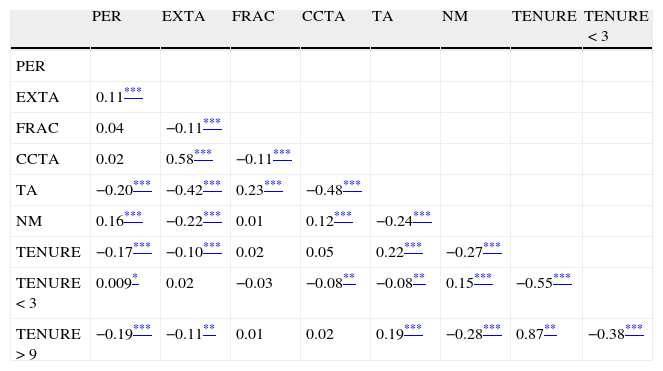

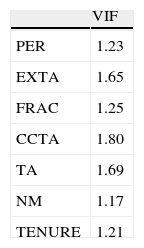

Table 3 shows Pearson's correlation coefficients, together with significance levels, for the independent variables used in the multivariate logistic regression. Interestingly, the positive and significant correlation between TENURE and TA shows that big companies tend to have lengthy audit relationships. Similarly, companies audited by Big4 auditors also have longer tenures compared with companies audited by nonBig4 firms. These results are supported when tenure is measured through the two dichotomous variables. As expected, we observe that nonBig4 auditors tend to audit relatively small companies, and that large firms are more able to avoid losses than small firms. Since correlation coefficients between independent variables are rather low (the maximum correlation coefficient, in absolute terms, between variables simultaneously included in the estimation is 0.58), multicollinearity will hardly affect our estimation results. Nevertheless, we have calculated variance inflation factors (VIF), shown in Table 4, in order to rule out the negative potential effects of multicollinearity in our estimation results. As expected, VIF show very low values (the maximum value is 1.80 for variable CCTA with an average of 1.43), thus supporting our previous view that multicollinearity will not affect our results.

Pearson correlations and levels of significance between independent variables.

| PER | EXTA | FRAC | CCTA | TA | NM | TENURE | TENURE<3 | |

| PER | ||||||||

| EXTA | 0.11*** | |||||||

| FRAC | 0.04 | −0.11*** | ||||||

| CCTA | 0.02 | 0.58*** | −0.11*** | |||||

| TA | −0.20*** | −0.42*** | 0.23*** | −0.48*** | ||||

| NM | 0.16*** | −0.22*** | 0.01 | 0.12*** | −0.24*** | |||

| TENURE | −0.17*** | −0.10*** | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.22*** | −0.27*** | ||

| TENURE<3 | 0.009* | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.08** | −0.08** | 0.15*** | −0.55*** | |

| TENURE>9 | −0.19*** | −0.11** | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.19*** | −0.28*** | 0.87** | −0.38*** |

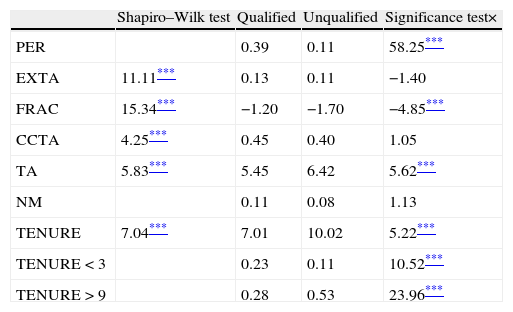

Before the estimation of the multivariate logistic regression, we have performed a univariate analysis of differences of means for subsamples of firms with qualified and unqualified audit reports. As expected, the Shapiro–Wilk test shown in Table 5 reveals that the hypothesis of normality is rejected for all independent variables, thus we have performed the Mann–Whitney test of differences of medians in order to assess the statistical significance of these differences. Median values of independent variables for each subsample, jointly with results of Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables and Pearson's chi-square test for the dichotomous variables PER, NM, TENURE<3 and TENURE>9 are shown in Table 5. Regarding our experimental variable TENURE, firms with unqualified reports show significantly longer tenures compared with firms with qualified reports (P-value<0.01). This result suggests a loss of independence with tenure, and is contrary to RBGB who reported that firms with unqualified reports had relatively shorter tenures. The same result is provided when audit tenure is measured through the two dichotomous variables TENURE<3 and TENURE>9. In both cases differences are statistically significant (P-value<0.01). We also observe significant differences between the two groups of firms in the predicted direction for variables: PER, FRAC and TA. Therefore, losses and lower levels of solvency are positively associated with a higher frequency of audit qualifications. Conversely, size is negatively associated with audit qualifications. Finally, no significant differences between the two groups of firms are observed for variables: EXTA, CCTA and NM.

Median values of independent variables for firms with qualified and with unqualified reports. For qualitative variables PER, NM, TENURE<3 and TENURE>9 mean values are provided.

| Shapiro–Wilk test | Qualified | Unqualified | Significance test× | |

| PER | 0.39 | 0.11 | 58.25*** | |

| EXTA | 11.11*** | 0.13 | 0.11 | −1.40 |

| FRAC | 15.34*** | −1.20 | −1.70 | −4.85*** |

| CCTA | 4.25*** | 0.45 | 0.40 | 1.05 |

| TA | 5.83*** | 5.45 | 6.42 | 5.62*** |

| NM | 0.11 | 0.08 | 1.13 | |

| TENURE | 7.04*** | 7.01 | 10.02 | 5.22*** |

| TENURE<3 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 10.52*** | |

| TENURE>9 | 0.28 | 0.53 | 23.96*** |

Significance tests:

Mann–Whitney test of differences of medians for variables: EXTA, FRAC, CCTA, TA, TENURE.

Pearson's chi-square test for the dichotomous variables: PER, NM, TENURE<3, TENURE>9.

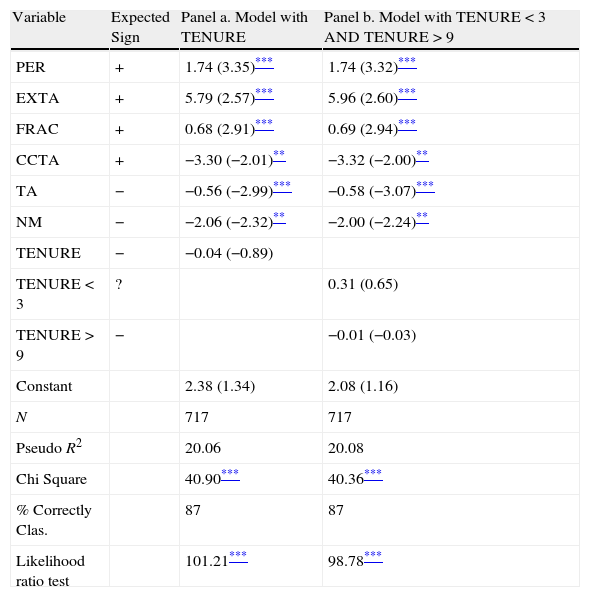

After the univariate analysis, we have carried out the investigation of the joint effect of the proposed variables on the likelihood of qualified reports, with a panel data estimation of the multivariate logistic model. Since most of our companies show unqualified reports for each of the years included in our research period, the use of a fixed effects logistic model would imply the loss of most a majority of our dataset. Thus, we have used a random effects logistic model. Significance tests have been implemented with robust standard errors. Table 6 shows the results of the estimation of the model with TENURE (panel A) and with TENURE<3 and TENURE>9 (panel B). Regarding panel A, the overall model is significant [P-value<0.000], with an adjusted pseudo R2 of 20%, slightly above the 18% reported by RBGB. The model correctly classifies 87% of cases [72% in RBGB]. It is important to note that the likelihood ratio test supports the use of a panel data estimation [Chi-Square=101.21; P-value<0.000], rather than the pooled logistic approach. Our variable of interest, TENURE, shows a negative coefficient, indicating that audit qualifications are less likely as tenure increases. However, the effect is not statistically significant at the required levels. Results from the univariate analysis suggested a loss of independence in long audit tenures. Nevertheless, the univariate analysis does not consider potential research confounds. Conversely, the multivariate approach controls for potential differences across the sample that may confound simple univariate comparisons (Becker, Defond, Jiambalvo, & Subramanyam, 1998). Therefore, according to the results provided by the estimation of the logistic model, we conclude that the length of the auditor–client relationship does not significantly affect the opinion of the audit report. Results do not support the hypothesis developed in the fourth section of this research. Similarly to RBGB we conclude that long audit tenures do not seem to compromise independence. However, unlike these authors we do not observe stronger levels of independence associated to longer tenures. Since both, the research period and the sample of firms are different in this paper and in RBGB, results are not directly comparable. Additionally, the estimation method is different between our paper and RBGB. While RBGB used pooled regression we have performed panel data estimation. The lack of significance of tenure on the likelihood of audit qualifications supports Ruiz-Barbadillo et al. (2006) investigation of the issuance of going-concern qualified opinions to financially distressed firms. Our main result contradicts available evidence reported by Vanstraelen (2000) for the Belgian market, showing that audit qualifications were less likely in lengthy audit engagements. However, in Vanstraelen's research, since control variables failed to account for the company's financial health, this result could be due to a variable omission problem. It should be noted that subsequent research for the Belgian audit market, limited to going-concern audit qualifications (Knechel & Vanstraelen, 2007) and including financial ratios among the regressors, has concluded that tenure did not have a significant effect on audit qualifications.

Results from random effects panel logistic regressions on the probability of issuing qualified opinions. Parameters estimates with z-values in parentheses.

| Variable | Expected Sign | Panel a. Model with TENURE | Panel b. Model with TENURE<3 AND TENURE>9 |

| PER | + | 1.74 (3.35)*** | 1.74 (3.32)*** |

| EXTA | + | 5.79 (2.57)*** | 5.96 (2.60)*** |

| FRAC | + | 0.68 (2.91)*** | 0.69 (2.94)*** |

| CCTA | + | −3.30 (−2.01)** | −3.32 (−2.00)** |

| TA | − | −0.56 (−2.99)*** | −0.58 (−3.07)*** |

| NM | − | −2.06 (−2.32)** | −2.00 (−2.24)** |

| TENURE | − | −0.04 (−0.89) | |

| TENURE<3 | ? | 0.31 (0.65) | |

| TENURE>9 | − | −0.01 (−0.03) | |

| Constant | 2.38 (1.34) | 2.08 (1.16) | |

| N | 717 | 717 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 20.06 | 20.08 | |

| Chi Square | 40.90*** | 40.36*** | |

| % Correctly Clas. | 87 | 87 | |

| Likelihood ratio test | 101.21*** | 98.78*** |

Focusing on control variables, in all cases they show significant effects on the probability of audit qualifications. Besides, with the only exception of CCTA, significance is observed in the predicted direction. Evidence supporting the results of the univariate analysis is observed for: PER, FRAC and TA. We also report significant effects for variables EXTA, CCTA and NM, although the univariate analysis did not provide significant differences for these variables depending on the nature of the audit report. Results for control variables support, for the most part, previous evidence reported by RBGB. Firms with solvency problems (FRAC) and those experiencing losses (PER) show higher probabilities of audit qualifications. As expected, non-Big4 auditors are less willing to issue qualified reports. The level of stocks (EXTA) positively affects the likelihood of audit qualifications. Similarly to RBGB but contrary to our initial predictions, CCTA shows a negative effect on the probability of qualified reports. In our opinion, this result could be due to the shortcomings of CCTA as a proxy of discretionary accruals, as explicitly recognized by RBGB. Besides, since working capital is also an indicator of liquidity, it seems rather reasonable that more liquid firms (those firms with higher values of CCTA) show a lower probability of audit qualifications. Regarding the effects of size, RBGB reported an unexpected positive sign for the coefficient associated with the variable TA, although only marginally significant. In our estimation, the effect of size on the likelihood of audit qualifications is negative, as expected, and highly significant (P-value<0.01), indicating that the probability of audit qualifications decreases with size.

Table 6 (panel B) shows the estimates of the model with the dichotomous variables TENURE<3 and TENURE>9. Results are very similar to those reported for the model with TENURE. Coefficients associated to TENURE<3 and TENURE>9 are not statistically significant at the usual levels. Therefore, our main conclusion that audit tenure does not impair independence is robust to various measures of tenure. Besides, since the coefficient associated to TENURE<3 is not significant, we conclude that a ‘honeymoon period’, as defined by Levinthal and Fichman (1988), does not seem to exist in the Spanish audit market. Results regarding control variables also remain unchanged.

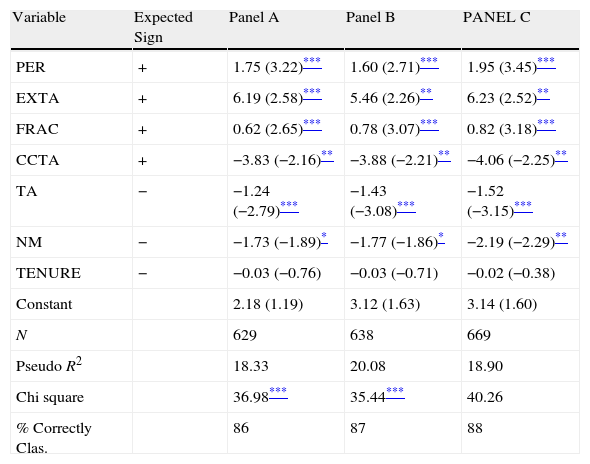

Sensitivity analysesWe have performed various sensitivity analyses in order to check the robustness of our results. All sensitivity analyses have been limited to the model with TENURE. First and most importantly, we want to rule out the potentially negative effects of measurement errors in our variable TENURE. As in RBGB, the first year available for this variable in this research was 1990. Since the first year of our research period is 2001, for those companies which did not change the auditor during the whole period 1990–2001, the value of TENURE in year 2001 was 12 years. However, we do not know the actual value of TENURE, since it could be 12 years or more. Such circumstance affects 21 companies in our sample representing 88 firm-year observations. Therefore, we have re-estimated our model after removing these observations. As it can be seen from Table 7 (panel A), results remain largely unchanged, compared with those reported by Table 6 (panel A). The second sensitivity analysis has been performed to control for the peculiarities of the year 2002. The year 2002 was an abnormal year for the audit market, not only because the fall of Arthur Andersen but also due to the enactment of the Financial Act. Therefore, we have re-estimated our model without including any observations from the year 2002. Table 7 (panel B) shows that results do not change compared with those reported for the whole research period. Finally, similar to Carey and Simnett (2006) research on the effects of tenure concerning the likelihood of a going-concern qualified opinion in the Australian market, we have included a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of our results to companies switching audit firms. As shown by Chow and Rice (1982), auditors’ switching could be indicative of low accounting quality. Thus, for those companies switching auditors our proposed model might not adequately capture the likelihood of audit qualifications. Accordingly, we have re-estimated the model after removing all observations with one year of tenure. As in the previous analyses, results shown by Table 7 (panel C) remain largely unchanged.

Sensitivity analyses. Panel A: Measurement of TENURE. Panel B: Effects of year 2002. Panel C: Auditor's switches.

| Variable | Expected Sign | Panel A | Panel B | PANEL C |

| PER | + | 1.75 (3.22)*** | 1.60 (2.71)*** | 1.95 (3.45)*** |

| EXTA | + | 6.19 (2.58)*** | 5.46 (2.26)** | 6.23 (2.52)** |

| FRAC | + | 0.62 (2.65)*** | 0.78 (3.07)*** | 0.82 (3.18)*** |

| CCTA | + | −3.83 (−2.16)** | −3.88 (−2.21)** | −4.06 (−2.25)** |

| TA | − | −1.24 (−2.79)*** | −1.43 (−3.08)*** | −1.52 (−3.15)*** |

| NM | − | −1.73 (−1.89)* | −1.77 (−1.86)* | −2.19 (−2.29)** |

| TENURE | − | −0.03 (−0.76) | −0.03 (−0.71) | −0.02 (−0.38) |

| Constant | 2.18 (1.19) | 3.12 (1.63) | 3.14 (1.60) | |

| N | 629 | 638 | 669 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 18.33 | 20.08 | 18.90 | |

| Chi square | 36.98*** | 35.44*** | 40.26 | |

| % Correctly Clas. | 86 | 87 | 88 |

Research concerning auditor independence has been strongly encouraged by the European Commission's publication of the Green Paper on Audit Policy, (EC, 2010). The document questions that the actual regulatory framework established by the revised 8th Directive on Company Law, could suffice to guarantee auditor independence. The main goal of this research has been to provide new evidence regarding the effects of tenure on auditor independence, without restricting the analysis to audit qualifications for reasons of going-concern and to financially stressed firms. Previous research in low litigation risk environments by Vanstraelen (2000) and RBGB have provided contradictory results. Contrary to Vanstraelen (2000) who reported a negative and statistically significant effect of tenure on the likelihood of qualified opinions, and RBGB who concluded in the opposite way, our results indicate that tenure does not affect the opinion of the audit report. It should also be noted that both papers analyzed the tenure-audit qualification relationship before the fall of Arthur Andersen and the enactment of the SOX. The important changes suffered by the audit profession during the last decade have made it necessary to update previous research. Therefore, regarding the concerns expressed by the Green Paper, our results show that long audit tenure relationships do not seem to impair independence in the Spanish market. As a proof of soundness, results regarding control variables show significance in the predicted direction in all cases. It should also be noted that our results are robust to various measures of audit tenure, to potential measurement errors in our experimental variable tenure and to situations of auditors’ switching.

Results reported in this research involve some rather straightforward implications for policy-makers. Auditor rotation rules are supposed to provide some benefits in terms of auditor independence, while they will also involve an increase in learning costs for the audit sector associated to new clients. Our results show that establishing a mandatory rotation rule for the audit firm would not contribute to enhance independence, while it would undoubtedly increase costs for the audit sector.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors want to thank the useful comments made by the anonymous referees. We are also grateful to Isabel García-Sánchez for her help during the editorial process.