For most of the world's largest companies, reporting on non-financial information appears to be a continuing trend.

Communication of social and environmental dimensions of the company plays a key role in the sustainable development of organizations, and therefore should be investigated more in depth.

The aim of this empirical study is to analyse the extent to which Eurozone companies report on CSR indicators, according to the Integrated Scorecard Taxonomy Scoreboard of the Spanish Accounting and Business Association (AECA), and the factors that can influence its use.

A content analysis was conducted on the annual sustainability reports on the websites of 306 Eurozone companies listed in the STOXX Europe 600.

The results revealed an intensive use of corporate governance indicators, a moderate disclosure of environmental key performance indicators (KPIs), and a low use of social indicators. Our study also showed that there is an influence of sector, and the listing in DJSI on the extent of sustainability reporting.

Para la mayoría de las empresas más grandes del mundo, la presentación de información no-financiera en sus informes anuales parece ser una tendencia constante.

La comunicación de las dimensiones sociales y mediaombientales de la empresa desempeňa un papel clave en el desarrollo sostenible de las organizaciones y, por lo tanto, debería ser investigado más profundamente.

El objetivo de este estudio empírico es el de analizar el grado en que las empresas de la Eurozona informan sobre los indicadores de RSC recogidos en la “Integrated Scorecard Taxonomy” propuesta por la Asociación Española de Contabilidad y Administración de Empresas (AECA), y los factores que pueden influir en su utilización.

Se realizó un análisis de contenido de los informes anuales sobre RSC encontrados en las páginas web de las 306 empresas de la Eurozona que figuran en el STOXX Europe 600.

Los resultados revelan un uso intensivo de los indicadores de gobierno corporativo, un uso moderado de los indicadores medioambientales y un bajo uso de los indicadores sociales. Nuestro estudio también demuestra que el sector y la inclusión de la empresa en DJSI influyen el nivel de divulgación de los indicadores sostenibles.

We are currently witnessing a shift from traditional reporting models focused mostly on financial and historical data to new forms of reporting, which adopt the triple bottom line approach and thus also include corporate social responsibility disclosure. Companies have recently struggled with increased pressure from internal and external stakeholders to report not only on financial but also on their social and environmental performance. Triple bottom line reporting refers to corporate sustainability reporting, which includes non-financial key performance indicators (environmental, social). Therefore, it is dedicated to a broader set of stakeholders, not just shareholders (Ballou, Heitger, & Landes, 2006). Sustainability reports serve as a tool to change external perceptions, to instigate dialogue with stakeholders and to play an important role in communication and relationship building between the organisations and stakeholders. Hence, examining the reasons and methods of companies’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting appears a promising field of research, and sustainability reporting becomes the subject of increased attention from the business as well as the academic community.

Due to the pressure from different stakeholders to be more transparent about company's dealings, large listed companies have been forced to report beyond the obligatory income statement and disclose more information about their activities and their social and environmental impacts on society. The aim of this study is to analyse the response of Eurozone companies to the challenge of CSR reporting by adopting the framework developed by the Spanish Accounting and Business Association (AECA). This study also offers a validation of AECA's indicators at the Eurozone level providing new insights for further development of the Integrated Scorecard (IS) taxonomy, which is on its way to gaining wider international acceptance. Additionally, we aimed to identify the factors that can influence the level of CSR reporting. The results revealed an intensive use of corporate governance indicators, a moderate disclosure of environmental key performance indicators (KPIs) and a low use of social indicators. Our study also showed that there is an influence of sector, and the listing in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI) on the extent of sustainability reporting.

A considerable amount of literature has been published on CSR. The first serious discussions of that topic emerged during the 1950s, when Bowen introduced the idea of social responsibility of a businessman in a wider sphere than pure profit seeking. Hence it is a product of 20th century (Carroll, 1991). More recently, the importance of CSR behaviour of companies and the need for CSR reporting arose as a response to many corporate scandals, financial crises, climate change, the commitment to a lower-carbon future and concern about labour rights, product safety, poverty reduction, etc. (Noronha, Tou, Cynthia, & Guan, 2012). In other words, it became a necessary tool in order to seek sustainable development and should be more than just an effective public relations tool adopted by a company to increase corporate profitability (Tinker & Niemark, 1987).

CSR reporting is mostly voluntarily based, but there are some countries with regulations making disclosure on CSR mandatory. Regarding the non-financial reporting regulations, governments and stock exchanges play an important role in promoting it. They are responsible for issuing relevant legislation and standards concerning the mandatory disclosures on CSR issues (Noronha et al., 2012). In Europe, there are already some regulations regarding the CSR disclosure in countries like Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, Germany, France, United Kingdom, Switzerland, and France.

Over the last decade, various standards were promoted and elaborated at a global level. Marimon, Alonso-Almeida, and Rodríguez (2012) provide a brief classification of corporate responsibility standards including UN Global Compact Principles, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, GRI, ISO 26000, AA1000, ISO 14001 and SA88000. However, a need for an internationally recognised and generally accepted framework to achieve the uniformity in CSR reporting still persists.

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines, developed in 1997, deserve a particular attention as they are today the most widely used (Ballou et al., 2006; Roca & Searcy, 2012). GRI reports currently approach forty percent of all corporate responsibility reports worldwide (Marimon et al., 2012) and according to results reported by Welford (2004) and Rowe (2006), Europe has the highest number of certifications in the GRI. Outtes-Wanderley, Soares, Lucian, Farache, and de Sousa Filho Milton (2008) stressed that the reason behind this could be that developed nations such as Eurozone countries implement practical actions that stimulate CSR development. GRI disclosure is based on triple bottom line including three sets of indicators (economic, environmental and social). Even though GRI reporting has spread around the world, there is still criticism relating to the large number of indicators proposed (84 indicators), and the fact that it is quite expensive for companies to prepare the report in accordance with GRI standards, which might be the reasons for the ongoing reluctance of some companies to adopt this framework.

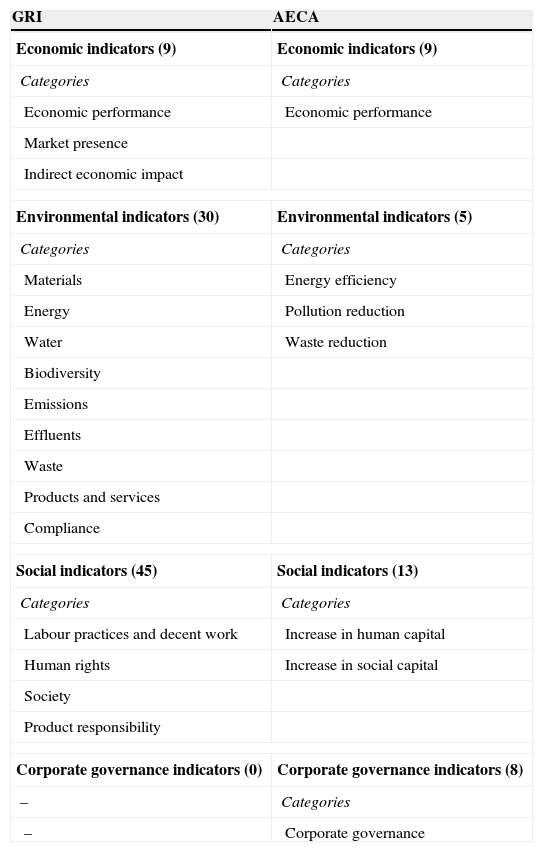

The Spanish Accounting and Business Association (AECA, Asociación Española de Contabilidad y Administración de Empresas) has developed an XBRL taxonomy for Integrated Reporting (Integrated Scorecard, IS), proposing a set of KPIs for the financial, social, environmental and corporate governance behaviour of companies. The use of the taxonomy is intended to promote comparability among companies, to increase corporate transparency and research in the field of CSR, in accordance with the requirements and proposals of the International Integrated Reporting Committee (IIRC). Among the proposed KPIs, there is a set of indicators for CSR and corporate governance (CG) that can be used to assess current reporting practices in that field. AECA's project should solve, for example, the lack of balance among the indicators in many frameworks and move from abstract to concrete indicators (e.g. GRI reports provide only a narrative part for corporate governance and no concrete indicators). In the Appendix 1, the main differences between AECA's Integrated Scorecard and GRI framework (version G3.1) are highlighted.

Although the current shape of AECA's Integrated Scorecard is quite new and might be seen as only nationally valid, it belongs to the acknowledged taxonomies recognised by XBRL International as being in compliance with the XBRL Specification. This taxonomy was first internationally recognised in December 2007, and was known as RSC Taxonomy for Corporate Social Responsibility. The updated version known as RSC – CCI Scoreboard for Corporate Social Responsibility Taxonomy gained XBRL approval in June 2010 and the current version, IS-FESG Integrated Scoreboard Taxonomy, was approved in April 2013. This acknowledgement gives the AECA's IS international merit (XBRL, 2013).

As AECA's IS provides quite a comprehensive set of indicators responding to the needs of integrated reporting (with a reasonable number of indicators) which belong to the international XBRL standards, we decided to use it as a benchmark for the purposes of our study.

2Literature review and hypotheses2.1Previous studies on CSR reportingMovement towards sustainable development resulted in increased pressure from different stakeholder groups to report on ESG (environmental, social governance indicators). Consequently, over the past decade, companies have been asked to improve transparency in reporting on their CSR performance (Arvidsson, 2010; Dando & Swift, 2003). According to the survey conducted by KPMG (2011), 95% of the 250 largest global companies currently report on CSR issues. Hence, the area of reporting practices of companies appears to be a promising field of research for academics.

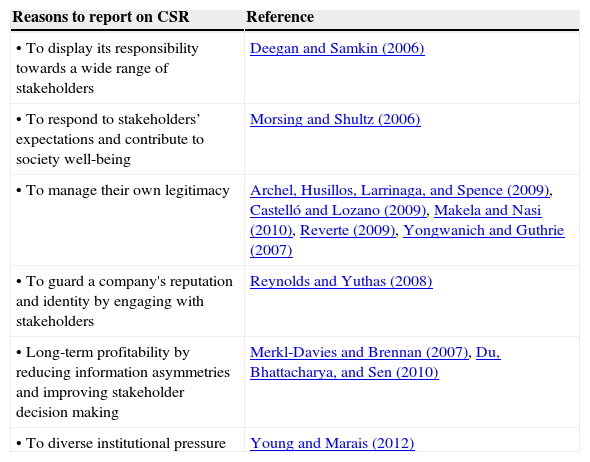

The study of Young and Marais (2012) can be considered a contribution to this field by conducting a content analysis of a number of studies regarding a company's CSR and providing an organised set of reasons why companies report on CSR. We organised this set of reasons in Table 1.

CSR reporting reasons.

| Reasons to report on CSR | Reference |

|---|---|

| • To display its responsibility towards a wide range of stakeholders | Deegan and Samkin (2006) |

| • To respond to stakeholders’ expectations and contribute to society well-being | Morsing and Shultz (2006) |

| • To manage their own legitimacy | Archel, Husillos, Larrinaga, and Spence (2009), Castelló and Lozano (2009), Makela and Nasi (2010), Reverte (2009), Yongwanich and Guthrie (2007) |

| • To guard a company's reputation and identity by engaging with stakeholders | Reynolds and Yuthas (2008) |

| • Long-term profitability by reducing information asymmetries and improving stakeholder decision making | Merkl-Davies and Brennan (2007), Du, Bhattacharya, and Sen (2010) |

| • To diverse institutional pressure | Young and Marais (2012) |

There is rich evidence and diverse studies conducted on the topic of CSR and reporting. However, our focus was on the literature which is the most relevant and connected to our study. Previous studies have used different measures to gauge CSR information disclosure varying from simple methods such as word, or page count of CSR reports to the level of standardized information in terms of the GRI guidelines or other internationally recognized guidelines (Ferrero, Garcia-Sanchez, & Cuadrado-Ballesteros, 2013).

The study of Font, Walmsley, Cogotti, McCombes, and Häusler (2012) focused on testing the gap between CSR claims and actual practices, benchmarking the practices of the companies operating in the European leisure market. Based on their findings, corporate reporting is not necessarily reflective of actual operations. Moreover, they point out an inward looking socio-economic policies with a little attention of impacts on the destination as well as a limited customer engagement approach.

The relation between corporate social responsibility reporting and controversial industry sectors has been previously examined as well. A further study by Weber, Diaz, and Schwegler (2012) analysed the performance of the financial sector with respect to CSR and sustainability and made a comparison between the financial sector and other sectors. Their findings suggest that financial sector performance is relatively low regarding CSR in general and sustainability reporting in contrast to critical sector affecting the environment and society by direct emissions or the use of resources. Similar conclusions were reported by Frynas (2010), Reverte (2012), Snider, Hill, and Martin (2003), and Young and Marais (2012).

Tewari and Dave (2012) analysed the CSR communication of companies through their sustainability reports; the sample included Indian Companies and Multinational Companies operating in the Information and Technology sector in India. For the purposes of their study, GRI was taken as a measure of comparison to gauge the standardization of the sustainability reports. According to their findings, sustainability reports as a medium of CSR communication are quite ignored and only a few companies publish the sustainability report. However, the quality of the reports was on a high level.

Other studies attempted to understand the link between CSR disclosures financial/stock performance. In fact, there is rich evidence suggesting that CSR disclosure is value-relevant (Al-Tuwaijri, Christensen, & Hughes, 2004; Graham, Harvey, & Rajgopal, 2005; Margolis & Walsh, 2001) and that there is a link between CSR transparency and the financial performance of the company (Graves & Waddock, 2000; Orlitzky, Schmidt, & Rynes, 2003; Van de Velde, Vermeir, & Corten, 2005). They argue that the loyalty of stakeholders, which is based on CSR communication-measured stakeholder engagement, in turn leads to higher company performance. However, there are still problems in measuring CSR and financial performance and there are also those who claim that CSR affects a company's performance adversely (Henderson, 2005; Jensen, 2001).

According to the survey conducted by KPMG (2011), Spain is the world's leading country for CSR reporting (Sierra, Zorio, & García-Benau, 2012). This is why AECA's Integrated Scoreboard provides an interesting context for our study. According to the GRI report from 2009, Spain is the country with the highest number of published GRI reports and President Obama highlighted Spain as an example of a leading country with renewable energies (Reverte, 2012).

Our study can be considered to be a new avenue for research as we are the first to explore the CSR reporting practices of Eurozone companies against AECA's Integrated Scorecard, which gained international recognition from XBRL standards in 2013 (XBRL, 2013). The contribution of our study is to provide an overview of CSR reporting practices in the Eurozone.

2.2Socio-political theoriesNumerous theories have been applied by academics intending to give meaning to the existence of corporate disclosure of financial and non-financial (CSR) information. One of the issues is the idea of the information asymmetry between the different stakeholders, which was developed by Agency Theory. According to this theory, companies use the disclosure of different information related to a company's performance in order to decrease these asymmetries (Cormier, Magnan, & Van Velthoven, 2005). Much empirical research has used legitimacy and stakeholder theory to study CSR reporting (Deegan, 2002). Both theories point out that CSR disclosure is a way of information asymmetry reduction and can be therefore an effective tool to legitimize the company's activities among the wide range of its stakeholders. Thus, these theories overcome the limitation of Agency theory, which is mostly focused on monetary considerations (Ferrero et al., 2013).

Regarding the legitimacy theory, many authors concluded that insights into CSR disclosure stem particularly from this theoretical framework (Branco & Rodrigues, 2006; Deegan, 2002; Gray, Kouhy, & Lavers, 1995). According to legitimacy theory, companies are allowed to operate as an entity when they adopt the practices which are in compliance with societal norms, expectations and values (Suchman, 1995). When it comes to CSR, it also implies that a company can gain legitimacy by voluntarily disclosing environmental and social information (Deegan, 2002). Van Staden and Hooks (2007) pointed out that a company can adopt either reactive or proactive approach towards achieving legitimacy. Reactive approach refers to the CSR communication of the company as a reaction to some negative or critical events. Proactive approach means that a company tries to prevent legitimacy concerns from arising.

Over the years, a number of proxies were used to test legitimacy theory. A study conducted by Ratanajongkol, Davey, and Low (2006) noted a positive relationship between the industry and the extent of CSR disclosure. The result of this study was also supported by other authors such as Gray et al. (1995) and Amran and Devi (2008), who stated that companies operating in more environmentally sensitive sectors disclose more CSR information than those operating in less sensitive sectors. Hoffman (1999) stressed that companies operating within the same sector and country share many stakeholders who are interested in their practices. Thus, they create some kind of institutional context in which they benchmark each other in order to gain societal acceptance of their activities and legitimise their practices. Similarly, Gray et al. (1995) suggest that the reporting practices are related to industry and country effects highlighting the consistency with the legitimacy theory. Additionally, Castelló and Lozano (2009) claimed that belonging to the DJSI is an example of moral legitimacy. Thus, a membership in the DJSI is basically like spreading the message that the actions of the company are in compliance with the expectations of the society, and this could be considered a direct reflection of the corporate legitimacy. Campbell (2000), based on the observations emerging from his study, stated that a company discloses non-financial information such as those related to environmental or social issues, as a strategy to manage its legitimacy by showing that its activity is in keeping with social norms and beliefs and that it is acting in an environmentally responsible way.

Other authors adopted the stakeholder approach based upon the Stakeholder Theory (Longo, Mura, & Bonoli, 2005; Papasolomou-Doukakis, Krambia-Kapardis, & Katsioloudes, 2005; Uhlaner, van Goor-Balk, & Masurel, 2004). Stakeholder theory was first introduced in 1984 by Freeman and the core of this theory holds that companies have a social responsibility, meaning that they are obligated to consider the interests of all stakeholders groups affected by their actions. Therefore, not only shareholders but also other stakeholders of the company such as suppliers, customers, employees, etc. should be considered relevant in the decision-making process of the company. A company should seek to provide a balance between the interests of its diverse stakeholders and CSR reporting might be an effective tool to satisfy their information needs and minimize the information asymmetry. According to Freeman (1984) companies try to achieve higher transparency in order to gain the approval of its diverse stakeholders. CSR reporting is therefore used to engage with different stakeholders groups that are deemed essential for the viability of the company (Roberts, 1992; Ullmann, 1985). Additionally, stakeholder theory is considered to be easy to grasp by practitioners. The AECA's Integrated Scorecard is consistent with this theory in a sense that it provides information to all stakeholders by grouping the key performance indicators into four subcategories: economic, social, governance and environmental.

2.3HypothesesPrevious studies on CSR reporting have shown that there is a strong country effect influencing the level of sustainability reporting (Cormier & Magnan, 2007; Outtes-Wanderley et al., 2008; Waddock, 2008; Young & Marais, 2012) well grounded in the legitimacy theory. The country represents an institutional context in which the company has to legitimize its activities. Its effect may embed different aspects such as governance system and regulation (Delbard, 2008), employment protection and labour conditions (Crossland, 2007), environmental protection regulations (Antal & Sobczak, 2007) and others. As in recent years in Europe, where the issue of a public debt as a % of GDP has arisen, contribution to the debate on the country effect may be to explore whether the country's public debt can explain some differences in CSR reporting. Therefore, we divided the Eurozone countries into two groups: countries with a public debt below EU average (Austria, Finland, Germany, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, Spain), and countries above EU average (Belgium, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy and Portugal) (US Central Intelligence Agency, 2013). This led us to formulate our first hypothesis:H1 There is a relationship between the CSR disclosure and the country where the company is headquartered.

Many studies found a link between industry where the company operates and its CSR reporting practices (Azim, Ahmed, & Islam, 2009; Outtes-Wanderley et al., 2008). The previous research conducted by Azim et al. (2009) and Ogrizek (2002) revealed that financial services represent the leading sector. The study of Frynas (2010) stressed the high rank in terms of CSR reporting by the oil and gas sector. Outtes-Wanderley et al. (2008) came to the conclusion that the energy sector, banking and telecommunications report the most on sustainability. Hence, these studies are contradictory to the approach adopted by Young and Marais (2012), who distinguish the industry type in terms of high/low risk. Reverte (2012) also divided the industries based on their environmental sensitiveness. Similarly, Snider et al. (2003) stressed that companies operating in an industry with higher social and environmental impacts face stronger stakeholder demands for greater transparency. Facing this scrutiny, these companies are required to legitimize their actions more than companies operating in low risk sectors. As communication plays an important role in the legitimacy process, CSR disclosure might be a very effective tool to manage the perception and reputation of the company (Cho, Roberts, & Patten, 2010). Thus, based on the previous research, legitimacy theory, and stakeholder theory, in the present study two groups of industry sectors were created based on their critical/non-critical impact on the environment. Our second hypothesis was established:H2 There is a relationship between the CSR disclosure and the industry which the company operates in.

Over the past decade, CSR has gained even higher importance. The companies have been subjected to stricter financial scrutiny, and the growing expectations of different stakeholder groups led to pressure to address not only financial information, but also the information about environmental and social behavior reflecting the sustainability aspects of the company (Arvidsson, 2010; Skoloudis & Evangelinos, 2009). In 1999, the Dow Jones Sustainability Index was launched and currently is the world's most reliable benchmark for sustainability. The study of Castelló and Lozano (2009) stressed that belonging to the DJSI is an example of moral legitimacy. The DJSI family indexes comprise five different indexes from different economic zones. Listing considers a number of factors like business economics, corporate and risk management, branding, labour policies, social and environmental performance, etc. Therefore, being a member of the DJSI is a signal of CSR leadership showing that the activities of the company are congruent with the expectations of society, which represents a direct reflection of a company's legitimacy (Cho, Guidry, Hageman, & Patten, 2012; Fowler & Hope, 2007). It is therefore likely that a connection exists between the extent of reporting on AECA's CSR indicators and the fact that the company is listed in DJSI. Assuming that companies striving for the legitimacy intent to protect their membership in the index, they are more likely to disclose CSR information. According to this, our third hypothesis was formulated:H3 The extent of reporting on CSR indicators is associated with whether the company is listed in DJSI.

To examine the extent to which Eurozone companies report on CSR, a sample of 306 companies listed in the STOXX Europe 600 index (companies headquartered in the country with Euro currency) was explored. The sample included 19 subsectors and 12 countries. A content analysis of the annual reports (or separated sustainability reports) published on the official websites was conducted. The data were collected in 2012.

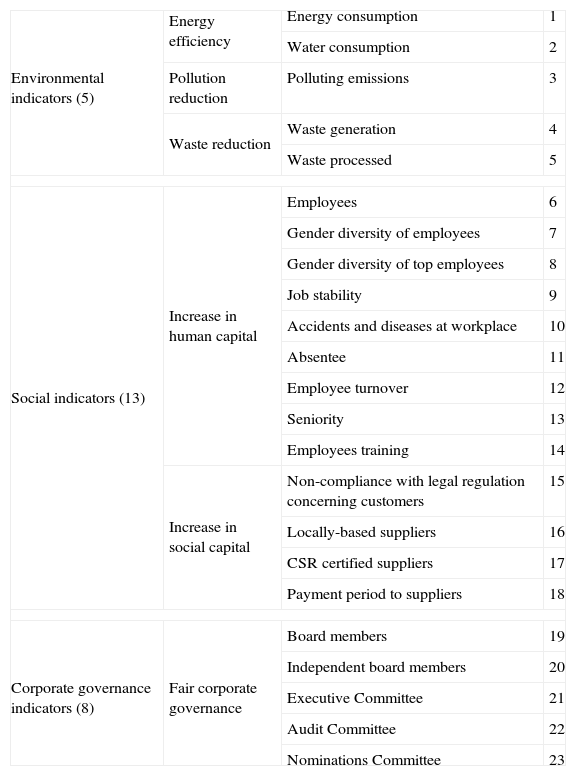

3.2Dependent variablesTo measure the extent of reporting, an index was developed, which was constructed by applying the AECA's indicators (Table 2). The index was calculated on a scale from 0 to 26, depending on the information which was or was not included in the sustainability report. A point has been assigned for each of the concrete indicators presented in the sustainability report of the company. Thus, the index consists of 26 indicators divided into three groups (environmental, social, and corporate governance indicators). Subsequently, three subindexes were created, an environmental reporting index (0–5), social reporting index (0–13), and corporate governance reporting index (0–8).

Indicators of the AECA's integrated scorecard.

| Environmental indicators (5) | Energy efficiency | Energy consumption | 1 |

| Water consumption | 2 | ||

| Pollution reduction | Polluting emissions | 3 | |

| Waste reduction | Waste generation | 4 | |

| Waste processed | 5 | ||

| Social indicators (13) | Increase in human capital | Employees | 6 |

| Gender diversity of employees | 7 | ||

| Gender diversity of top employees | 8 | ||

| Job stability | 9 | ||

| Accidents and diseases at workplace | 10 | ||

| Absentee | 11 | ||

| Employee turnover | 12 | ||

| Seniority | 13 | ||

| Employees training | 14 | ||

| Increase in social capital | Non-compliance with legal regulation concerning customers | 15 | |

| Locally-based suppliers | 16 | ||

| CSR certified suppliers | 17 | ||

| Payment period to suppliers | 18 | ||

| Corporate governance indicators (8) | Fair corporate governance | Board members | 19 |

| Independent board members | 20 | ||

| Executive Committee | 21 | ||

| Audit Committee | 22 | ||

| Nominations Committee | 23 | ||

With regard to legitimacy and stakeholder theory, a number of independent variables (predictors) widely applied in previous studies were used (Bazley, Brown, & Izan, 1985; Larran & Giner, 2002; Utama, 2012; Wagenhofer, 1990). Respectively, we aimed to determine whether the country of origin (H1), industry (H2), and listing in DJSI (H3) are predictors of the level of CSR disclosure measured by the designed index.

For the purposes of our study, Eurozone countries were divided into two groups: countries with a public debt below EU average (Austria, Finland, Germany, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, Spain), and countries above EU average (Belgium, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy and Portugal) (US Central Intelligence Agency, 2013). Coding schema was designed as follows: “1” for countries with a public debt below EU average and “0” otherwise.

Regarding the industry, our sample includes 19 supersectors which were further divided into two groups, critical and non-critical sectors (coding: “1” for critical and “0” otherwise), adopting a similar approach to Cho et al. (2010), and Cho and Patten (2007) who were using a dichotomous one/zero coding scheme to separate companies that operate in an environmentally sensitive/non-sensitive sector.

Furthermore, we distinguished companies based on whether they are listed on the DJSI. Subsequently, two groups of companies were created, those which were listed on the DJSI (1) and those which were not (0). Similar approach was applied by Castelló and Lozano (2009), Fowler and Hope (2007), and Cho et al. (2012).

3.4Control variablesAdditionally, we tested two control variables, profitability and the size of the company, and their relationship with CSR disclosure.

According to Tagesson, Blank, Broberg, and Collin (2009), most studies have reported a positive relationship between the size of the company and the extent of CSR disclosure. The size of the company was used as a control variable in many previous studies regarding its influence on the level of sustainability reporting (Gallo & Christensen, 2011; Levy, Szejnwald, & de Jong, 2010; Moroney, Windsor, & Aw, 2011; Simnett, Vanstraelen, & Chua, 2009). There is an assumption that larger companies are subject to greater pressure in terms of responding to stakeholder demands and that is why they tend to report more on their CSR practices in order to legitimize their activities (Burke, Logsdon, Mitchell, Reiner, & Vogel, 1986). The size was usually measured by the number of employees (Sharma, 2002) or the natural logarithm of total assets as a proxy for the company size (Clarkson, Li, Richardson, & Vasvari, 2008; Trotman & Bradley, 1981). In our case, the size of the company was measured by the logarithmically transformed market capitalization. Accordingly, we expect that the extent of CSR reporting is positively associated with the company size.

Based on the literature, most applications of value relevance of CSR disclosure focused on accounting variables (Brammer & Pavelin, 2008; Holthausen & Watts, 2001; Ohlson, 1995). Previous studies analysing the relationship between sustainability reporting and a company's financial performance using profitability as a financial variable were, for example, conducted by Clarkson et al. (2008) and Sierra et al. (2012). Nevertheless, the researchers reached opposing conclusions. Studies conducted by Al-Tuwaijri et al. (2004), Graves and Waddock (2000), Margolis and Walsh (2001), McWilliams, Siegel, & Wright (2006), Orlitzky et al. (2003), Shadewitz and Niskala (2010), and Van de Velde et al. (2005) found a positive relationship between the sustainability disclosure and the company's financial performance. On the other hand, Carnevale, Mazzuca, & Venturini (2012), Henderson (2005), Jensen (2001), and Levy et al. (2010) came to the contradictory results. Seeking to contribute to this debate, we tried to measure the relationship between the CSR reporting and the financial performance of the company. To measure profitability for the purposes of the present study, we used the net profit margin. We assume that there is a positive relationship between the profitability of the company and CSR reporting.

3.5Independent and control variables testingFor variables testing, different statistical methods were applied. On the univariable level, Mann–Whitney test and Spearman coefficient were used for non-parametric dependent variables, while t-test and Pearson correlation coefficient were applied for parametric dependent variables. Regarding the multivariate statistics, the ordinary least squares (OLS) model as well as the cluster analysis was conducted.

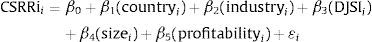

With regard to the ordinary least squares (OLS), the association between the CSR index and the proposed variables such as country, industry, listing in DJSI, size, and profitability was evaluated by estimating the following OLS regression:

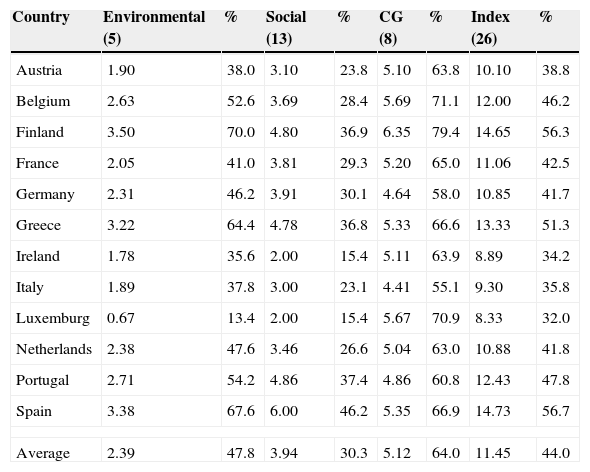

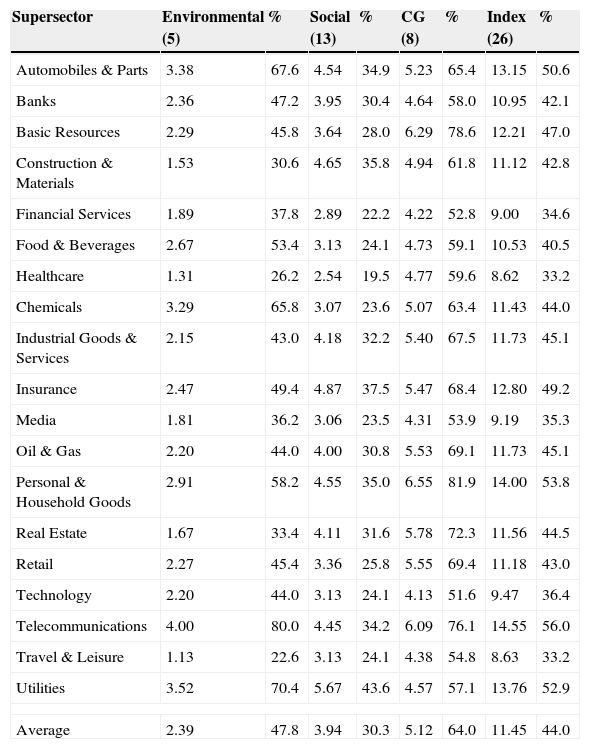

where CSRRii=Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting Index (reporting on environmental, social, and corporate governance indicators) of the company i, countryi=dummy variable: 1 is given when the company is headquartered in the country with the public dept below the European average and 0 otherwise, industryi=dummy variable: 1 is given when the company operates in critical sector and 0 otherwise; DJSIi=dummy variable: 1 is given when the company is included in DJSI and 0 otherwise; sizei=size of the company i measured by market capitalization; profitabilityi=profitability of the company i measured by net profit; ¿i=residual term of the company i; β0 is a constant, β1 to β5 are the coefficients.4Results4.1Descriptive statisticsThe extent to which Eurozone companies report on CSR and CG according to the AECA's framework is shown in Tables 3 and 4 (average index per country) and 4 (average index per super-sector). The average disclosure index was 11.45 (44% of the 26 KPIs to be reported). The average sub-indexes were 2.39 (47.8%) for environmental disclosure, 3.94 (30.3%) for social KPIs and 5.12 (64%) for corporate governance indicators.

Average index per country.

| Country | Environmental (5) | % | Social (13) | % | CG (8) | % | Index (26) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 1.90 | 38.0 | 3.10 | 23.8 | 5.10 | 63.8 | 10.10 | 38.8 |

| Belgium | 2.63 | 52.6 | 3.69 | 28.4 | 5.69 | 71.1 | 12.00 | 46.2 |

| Finland | 3.50 | 70.0 | 4.80 | 36.9 | 6.35 | 79.4 | 14.65 | 56.3 |

| France | 2.05 | 41.0 | 3.81 | 29.3 | 5.20 | 65.0 | 11.06 | 42.5 |

| Germany | 2.31 | 46.2 | 3.91 | 30.1 | 4.64 | 58.0 | 10.85 | 41.7 |

| Greece | 3.22 | 64.4 | 4.78 | 36.8 | 5.33 | 66.6 | 13.33 | 51.3 |

| Ireland | 1.78 | 35.6 | 2.00 | 15.4 | 5.11 | 63.9 | 8.89 | 34.2 |

| Italy | 1.89 | 37.8 | 3.00 | 23.1 | 4.41 | 55.1 | 9.30 | 35.8 |

| Luxemburg | 0.67 | 13.4 | 2.00 | 15.4 | 5.67 | 70.9 | 8.33 | 32.0 |

| Netherlands | 2.38 | 47.6 | 3.46 | 26.6 | 5.04 | 63.0 | 10.88 | 41.8 |

| Portugal | 2.71 | 54.2 | 4.86 | 37.4 | 4.86 | 60.8 | 12.43 | 47.8 |

| Spain | 3.38 | 67.6 | 6.00 | 46.2 | 5.35 | 66.9 | 14.73 | 56.7 |

| Average | 2.39 | 47.8 | 3.94 | 30.3 | 5.12 | 64.0 | 11.45 | 44.0 |

Average index per super-sector.

| Supersector | Environmental (5) | % | Social (13) | % | CG (8) | % | Index (26) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automobiles & Parts | 3.38 | 67.6 | 4.54 | 34.9 | 5.23 | 65.4 | 13.15 | 50.6 |

| Banks | 2.36 | 47.2 | 3.95 | 30.4 | 4.64 | 58.0 | 10.95 | 42.1 |

| Basic Resources | 2.29 | 45.8 | 3.64 | 28.0 | 6.29 | 78.6 | 12.21 | 47.0 |

| Construction & Materials | 1.53 | 30.6 | 4.65 | 35.8 | 4.94 | 61.8 | 11.12 | 42.8 |

| Financial Services | 1.89 | 37.8 | 2.89 | 22.2 | 4.22 | 52.8 | 9.00 | 34.6 |

| Food & Beverages | 2.67 | 53.4 | 3.13 | 24.1 | 4.73 | 59.1 | 10.53 | 40.5 |

| Healthcare | 1.31 | 26.2 | 2.54 | 19.5 | 4.77 | 59.6 | 8.62 | 33.2 |

| Chemicals | 3.29 | 65.8 | 3.07 | 23.6 | 5.07 | 63.4 | 11.43 | 44.0 |

| Industrial Goods & Services | 2.15 | 43.0 | 4.18 | 32.2 | 5.40 | 67.5 | 11.73 | 45.1 |

| Insurance | 2.47 | 49.4 | 4.87 | 37.5 | 5.47 | 68.4 | 12.80 | 49.2 |

| Media | 1.81 | 36.2 | 3.06 | 23.5 | 4.31 | 53.9 | 9.19 | 35.3 |

| Oil & Gas | 2.20 | 44.0 | 4.00 | 30.8 | 5.53 | 69.1 | 11.73 | 45.1 |

| Personal & Household Goods | 2.91 | 58.2 | 4.55 | 35.0 | 6.55 | 81.9 | 14.00 | 53.8 |

| Real Estate | 1.67 | 33.4 | 4.11 | 31.6 | 5.78 | 72.3 | 11.56 | 44.5 |

| Retail | 2.27 | 45.4 | 3.36 | 25.8 | 5.55 | 69.4 | 11.18 | 43.0 |

| Technology | 2.20 | 44.0 | 3.13 | 24.1 | 4.13 | 51.6 | 9.47 | 36.4 |

| Telecommunications | 4.00 | 80.0 | 4.45 | 34.2 | 6.09 | 76.1 | 14.55 | 56.0 |

| Travel & Leisure | 1.13 | 22.6 | 3.13 | 24.1 | 4.38 | 54.8 | 8.63 | 33.2 |

| Utilities | 3.52 | 70.4 | 5.67 | 43.6 | 4.57 | 57.1 | 13.76 | 52.9 |

| Average | 2.39 | 47.8 | 3.94 | 30.3 | 5.12 | 64.0 | 11.45 | 44.0 |

Countries with the highest average index were: Spain 14.73 (56.7%), Finland 14.65 (56.3%), Greece 13.33 (51.3%), Portugal 12.43 (47.8%) and Belgium 12 (46.2%). The lowest rate was detected in Luxemburg 8.33 (32%), Ireland 8.89 (34.2%), Italy 9.30 (35.8%) and Austria 10.10 (38.8%). The highest average sub-indexes, 70% and above, were: Finland (70%) for environmental disclosure and Finland (79.4%), Belgium (71.1%) and Luxembourg (70.9%) for corporate governance indicators. No country was found to report on social KPIs beyond 50%.

The highest average index was detected in the super-sectors: Telecommunications 14.55 (56%), Personal and Household Goods 14 (53.8%), Utilities 13.76 (52.9%) and Automobiles and Parts 13.15 (50.6%). The lowest were: Healthcare 8.62 (33.2%), Travel and Leisure 8.63 (33.2%), Financial Services 9 (34.6%), Media 9.19 (35.3%) and Technology 9.47 (36.4%). The highest average sub-indexes, 70% and above, were: Telecommunications (80%) and Utilities (70.4%) for environmental disclosure and Personal and Household Goods (81.9%), Basic Resources (78.6%), Telecommunications (76.1%) and Real Estate (72.3%) for corporate governance indicators. No super-sector was found to report on social KPIs beyond 50%.

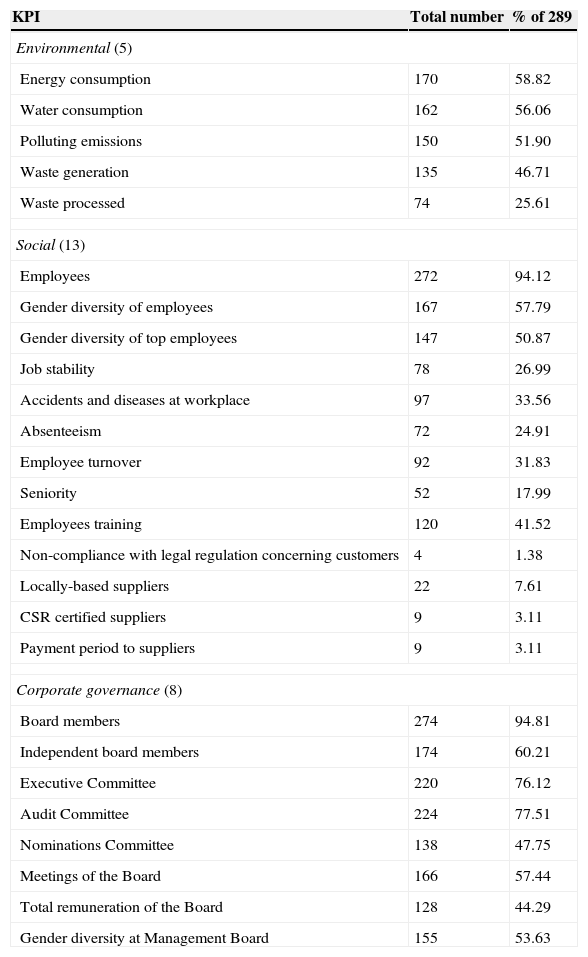

Regarding KPIs’ acceptance/usage (Table 5): the highest reporting activity was detected on indicators such as Board members (94.81%), number of employees (94.12%), Audit Committee (77.51) or Executive Committee (76.12). More than 50% of companies were reporting on energy and water consumption, polluting emissions, gender diversity of employees and top employees, independent board members, meetings of the board and gender diversity at management board. Finally, the representation of social KPIs other than human capital indicators was extremely low, i.e. non-compliance with legal regulation concerning customers (1.38%), CSR certified suppliers (3.11%), payment period to suppliers (3.11%) or locally based suppliers (7.61%).

Reporting on AECA's non-financial (NI) indicators by Eurozone companies.

| KPI | Total number | % of 289 |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental (5) | ||

| Energy consumption | 170 | 58.82 |

| Water consumption | 162 | 56.06 |

| Polluting emissions | 150 | 51.90 |

| Waste generation | 135 | 46.71 |

| Waste processed | 74 | 25.61 |

| Social (13) | ||

| Employees | 272 | 94.12 |

| Gender diversity of employees | 167 | 57.79 |

| Gender diversity of top employees | 147 | 50.87 |

| Job stability | 78 | 26.99 |

| Accidents and diseases at workplace | 97 | 33.56 |

| Absenteeism | 72 | 24.91 |

| Employee turnover | 92 | 31.83 |

| Seniority | 52 | 17.99 |

| Employees training | 120 | 41.52 |

| Non-compliance with legal regulation concerning customers | 4 | 1.38 |

| Locally-based suppliers | 22 | 7.61 |

| CSR certified suppliers | 9 | 3.11 |

| Payment period to suppliers | 9 | 3.11 |

| Corporate governance (8) | ||

| Board members | 274 | 94.81 |

| Independent board members | 174 | 60.21 |

| Executive Committee | 220 | 76.12 |

| Audit Committee | 224 | 77.51 |

| Nominations Committee | 138 | 47.75 |

| Meetings of the Board | 166 | 57.44 |

| Total remuneration of the Board | 128 | 44.29 |

| Gender diversity at Management Board | 155 | 53.63 |

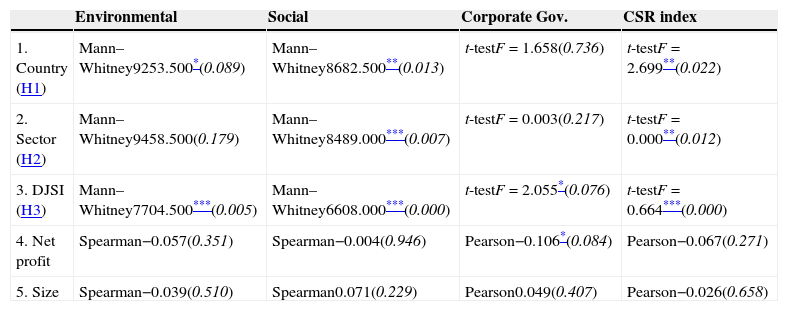

The set of hypotheses analysed the impact of three independent variables (country, sector, listing in DJSI) and two control variables (size and profitability) on the extent of CSR reporting against AECA's framework. As a dependent variable (CSR reporting index) implies a normal distribution (mean=11.45, median=12.00, mode=10.00), parametric alternatives of correlation index and tests were applied to measure the relationship between the variables.

To measure the median variances between the dependent variable – CSR reporting index and binary variables such as country (0=country with the public debt above the European average, 1=country with the public debt below the European average), sector (0=non-critical sector, 1=critical or environmentally sensitive sector) and the listing in DJSI (0=not listed, 1=listed), the t-test was applied. For the scale variable, size of the company (based on the market capitalisation) and net profit, Pearson correlation coefficient was applied. The results are presented in Table 6.

Hypotheses and control variables testing.

| Environmental | Social | Corporate Gov. | CSR index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Country (H1) | Mann–Whitney9253.500*(0.089) | Mann–Whitney8682.500**(0.013) | t-testF=1.658(0.736) | t-testF=2.699**(0.022) |

| 2. Sector (H2) | Mann–Whitney9458.500(0.179) | Mann–Whitney8489.000***(0.007) | t-testF=0.003(0.217) | t-testF=0.000**(0.012) |

| 3. DJSI (H3) | Mann–Whitney7704.500***(0.005) | Mann–Whitney6608.000***(0.000) | t-testF=2.055*(0.076) | t-testF=0.664***(0.000) |

| 4. Net profit | Spearman−0.057(0.351) | Spearman−0.004(0.946) | Pearson−0.106*(0.084) | Pearson−0.067(0.271) |

| 5. Size | Spearman−0.039(0.510) | Spearman0.071(0.229) | Pearson0.049(0.407) | Pearson−0.026(0.658) |

This implies that companies listed in DJSI have higher CSR reporting index compared with those not listed. There was also a relationship found between the companies operating in an environmentally sensitive sector and their tendency to report more on CSR practices. Another finding which emerged from this study was that the companies headquartered in countries with public debt lower than the European average tend to have higher sustainability disclosure as well.

These hypotheses were confirmed on the probability level p<0.05 (H1 and H2) and p<0.01 (H3). Hence, it can be concluded that the results support the hypotheses H1–H3.

Based on the result of Pearson's correlation coefficient, it can be concluded that there is no correlation between the CSR disclosure level and the size or profitability of the company. Thus, the size and profitability of the company do not affect the CSR reporting practices as the p-value was higher than 0.05 in both cases. Hence, the control variables analysed in this study were not supported.

Furthermore, we examined the impact of chosen factors (country, sector, DJSI, net profit, size) on the partial disclosure indexes (social, environmental and corporate governance). As environmental and social index do not show a normal distribution, non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney) and correlation coefficient (Spearman) were applied. There was a normal distribution found for corporate governance indicator and, therefore, the parametric alternatives such as t-test and Pearson correlation coefficient were applied. These results can also be seen in Table 6.

According to the results in our study, there was a sector effect detected on the social and total CSR index. A country effect was detected on the environmental, social, and total CSR index. Furthermore, DJSI listing effect on the environmental, social, corporate governance, and total CSR index was found as well. Regarding the profitability, a very low negative correlation was found between the net profit and corporate governance reporting index.

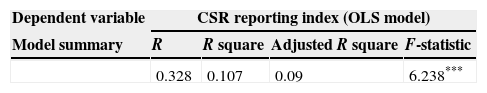

4.3Multivariate statistics – the ordinary least square (OLS) methodIn order to examine in depth the factors influencing a CSR index, the multivariate statistics was applied as can be seen in Table 7. To measure the impact of all tested variables on the extent of CSR reporting, the least squares method was applied, the model has been explained previously.

OLS model summary.

| Dependent variable | CSR reporting index (OLS model) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model summary | R | R square | Adjusted R square | F-statistic |

| 0.328 | 0.107 | 0.09 | 6.238*** | |

| Independent variables | Coef. | t-test | Sig. | Collinearity statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| (Constant) | 9.863 | 21.062 | 0.000 | ||

| Country | 0.850 | 1.596 | 0.176 | 0.948 | 1.055 |

| Sector | 1.301 | 2.488*** | 0.008 | 0.985 | 1.016 |

| DJSI | 2.271 | 4.117*** | 0.000 | 0.982 | 1.019 |

| Net profit | 0.000 | −1.304 | 0.142 | 0.987 | 1.014 |

| Size | −1.33E−05 | −0.965 | 0.793 | 0.974 | 1.027 |

| Dependent variable | Environmental reporting index (OLS model) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model summary | R | R square | Adjusted R square | F-statistic |

| 0.208 | 0.043 | 0.025 | 2.364** | |

| Independent variables | Coef. | t-test | Sig. | Collinearity statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| (Constant) | 1.959 | 9.359 | 0.000 | ||

| Country | 0.305 | 0.240 | 0.206 | 0.944 | 1.059 |

| Sector | 0.172 | 0.236 | 0.466 | 0.982 | 1.018 |

| DJSI | 0.680 | 2.736*** | 0.007 | 0.979 | 1.022 |

| Net profit | 8.460E−05 | 0.668 | 0.505 | 0.986 | 1.014 |

| Size | −3.682E−06 | −0.594 | 0.553 | 0.973 | 1.027 |

| Dependent variable | Social reporting index (OLS model) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model summary | R | R square | Adjusted R square | F-statistic |

| 0.302 | 0.091 | 0.074 | 5.273*** | |

| Independent variables | Coef. | t-test | Sig. | Collinearity statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| (Constant) | 3.046 | 12.037 | 0.000 | ||

| Country | 0.383 | 1.319 | 0.188 | 0.944 | 1.059 |

| Sector | 0.759 | 2.664*** | 0.008 | 0.982 | 1.018 |

| DJSI | 1.055 | 3.507*** | 0.001 | 0.979 | 1.022 |

| Net profit | 0.000 | −1.459 | 0.146 | 0.986 | 1.014 |

| Size | −1.162E−06 | −0.155 | 0.877 | 0.973 | 1.027 |

| Dependent variable | Corporate governance reporting index (OLS model) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model summary | R | R square | Adjusted R square | F-statistic |

| 0.201 | 0.041 | 0.022 | 2.217* | |

| Independent variables | Coef. | t-test | Sig. | Collinearity statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| (Constant) | 4.928 | 24.363 | 0.000 | ||

| Country | 0.103 | 0.445 | 0.657 | 0.944 | 1.059 |

| Sector | 0.308 | 1.351 | 0.178 | 0.982 | 1.018 |

| DJSI | 0.466 | 1.937* | 0.054 | 0.979 | 1.022 |

| Net profit | 0.000 | −1.832* | 0.068 | 0.986 | 1.014 |

| Size | −7.970E−06 | −1.330 | 0.185 | 0.973 | 1.027 |

*<0.1

**<0.05

***<0.01

According to the results shown in Table 7, based on the least squares method (R-squared=0.107, significance=0.000), we reached the conclusion that the CSR reporting index depends simultaneously on the sector where the company operates and its listing in DJSI. Even though the univariable analysis suggested a country effect, the multivariate statistics rejected this assumption based on the high significance level (for the CSR reporting index and all sub-indexes respectively). Very low negative correlation between the net profit and the corporate governance reporting index was detected as well as on the univariable level. The assumption that a multicollinearity might cause the exclusion of country in multivariate statistics was rejected because VIF factors are low (about 1) in all cases.

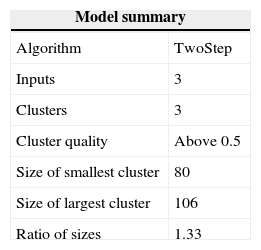

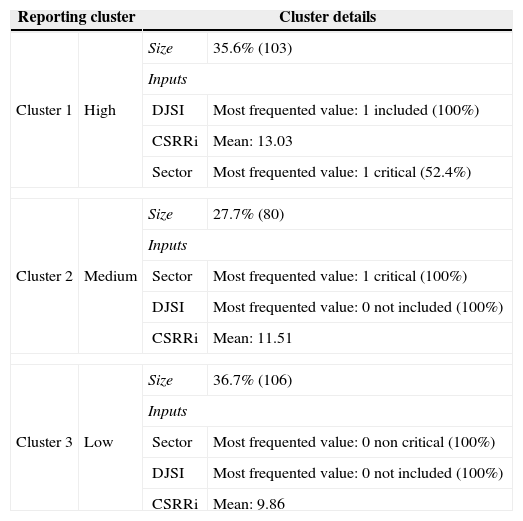

4.4Cluster analysisTo complete the statistics and confirm the results of the OLS, a cluster analysis with the three inputs: CSR reporting index, listing in DJSI, and sector was conducted. Model summary is provided in Table 8. The index measuring the cohesion and separation was above 0.5 which suggests a good cluster quality. Similarly, the ratio of sizes was under the acceptable level (1.33).

As the output of the cluster analysis, three clusters were obtained (Table 9). The first cluster represents 35.6% of the sample and refers to the group with the high extent of reporting (CSR reporting index mean: 13.03). This cluster includes the companies listed in DJSI and operating mainly in the critical sector. The second cluster consists of 27.7% companies from the sample and represents a group with the medium extent of CSR reporting (CSR reporting index mean: 11.51). This cluster includes only critical sector, but none of the companies were listed in DJSI. The third cluster includes 36.7% of the companies with the lowest extent of CSR reporting (CSR reporting index: 9.86). In this cluster all companies were from non-critical sector and none of them were included in DJSI.

Clusters.

| Reporting cluster | Cluster details | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | High | Size | 35.6% (103) |

| Inputs | |||

| DJSI | Most frequented value: 1 included (100%) | ||

| CSRRi | Mean: 13.03 | ||

| Sector | Most frequented value: 1 critical (52.4%) | ||

| Cluster 2 | Medium | Size | 27.7% (80) |

| Inputs | |||

| Sector | Most frequented value: 1 critical (100%) | ||

| DJSI | Most frequented value: 0 not included (100%) | ||

| CSRRi | Mean: 11.51 | ||

| Cluster 3 | Low | Size | 36.7% (106) |

| Inputs | |||

| Sector | Most frequented value: 0 non critical (100%) | ||

| DJSI | Most frequented value: 0 not included (100%) | ||

| CSRRi | Mean: 9.86 | ||

Firstly, we analysed the extent to which Eurozone companies report on CSR indicators according to the Spanish Accounting and Business Association's (AECA) framework. Secondly, we tried to find the factors influencing the extent of CSR reporting and explain the reasons for the low presence of social indicators.

According to our findings, the extent of Eurozone companies’ reporting practices on AECA's KPIs can be described as follows: an intensive use of corporate governance indicators, a moderate disclosure of environmental KPIs and a low use of social indicators. It should be highlighted that within the latter, the use of human capital indicators is also moderate, while other social indicators have an extremely low presence. The logic behind these findings is that regulated/compulsory information like corporate governance has to be disclosed more intensively than voluntary information like environmental or social information. Consequently, representativeness of AECA's KPIs for Eurozone companies can be considered high for corporate governance indicators, medium for environmental and social (human capital) KPIs and very low for social (other than human capital) indicators.

Secondly, we analysed different factors that can influence the extent of reporting. Size of the company has been used in a number of studies as a control variable that has an influence on the CSR disclosure (Burke et al., 1986; Tagesson et al., 2009). Haniffa & Cooke, 2005Haniffa and Cooke (2005, p. 395) and Branco and Rodrigues (2006) stated that large companies are socially more visible and, therefore, also more exposed to public scrutiny. Their studies show that there is a relationship between the size of the company and the extent of CSR disclosure. However, the results of our study are in contradiction to those authors as there was no significant correlation found.

A number of studies focused on analysing whether the financial performance has an impact on the CSR practices. However, their findings are often contradictory. In our study, we measured the relationship between the extent of CSR disclosure and the financial variables related to the profitability of the company (net profit). The study conducted by Sharma (2002) revealed that there is a relationship between the CSR practices and corporate financial performance. On the other hand, Carnevale et al. (2012) did not find any significant correlation between those variables. The results of our study also suggest that there is no significant correlation between the level of CSR disclosure and corporate financial performance.

Most studies also found that the sector where the company operates may have an impact on its disclosure practices. Research conducted by Gray et al. (1995), Amran and Devi (2008), Branco and Rodrigues (2008) and many others pointed out that disclosure practices and the extent of CSR disclosure differ significantly across industries. Thus, companies operating in more environmentally sensitive sectors disclose more in comparison with other sectors. Regarding the results which emerged from our study, sector effect was confirmed on the univariable as well as on the multivariate level adopting the OLS method. Additionally, the results of the cluster analysis revealed that companies operating in critical sector belong to the clusters of companies with the higher rates of CSR disclosure. These results are in line with legitimacy theory.

Based on the univariable statistics results of our study, the country where the company operates has also an impact on the extent of reporting. This finding is also explained and supported by legitimacy theory. However, our multivariate statistics using the least square method rejected a country effect.

There was, nevertheless, a positive relationship found between the extent of disclosure and listing in DJSI confirmed also by cluster analysis, where companies listed in DJSI belonged to the clusters of companies reporting more extensively on their CSR information.

6ConclusionAlthough the reporting on non-financial performance is not compulsory in most of the countries, there is an increased number of different groups of stakeholders that are demanding this disclosure in order to make informed decisions. Over time, a number of frameworks and standards have been proposed in relation to how to report on nonfinancial information but there is still an ongoing need for a systematic, standardized, and unified format of a CSR reporting framework.

AECA's Integrated Scorecard represents a set of concrete, measurable indicators based on various nationally and internationally accepted frameworks such as AA 1000, Caux Round Table Principles, DOMINI 400, EIRIS, EMAS, Ethical Trading Initiative, FTSE4 Good Index, Global Compact, GRI, ISO 9000 and 14001, SA8000.

An XBRL taxonomy was created based on the proposed Integrated Scorecard including not only financial, but also social, environmental, and corporate governance KPIs aiming to facilitate comparability and interchange of data. In June 2010, the taxonomy was for the first time officially acknowledged by XBRL, which gives AECA's IS international merit. The updated version, which also includes corporate governance indicators, IS-FESG Integrated Scoreboard Taxonomy, was approved by XBRL International in April 2013.

Using this framework we examined the CSR reporting practices in the Eurozone countries. Additionally, we tested a number of factors, which are well grounded by legitimacy and stakeholder theory to identify their possible effects on the extent of CSR disclosure finding that sector and DJSI membership are the strongest factors influencing the level of non-financial disclosure.

Practical implication in this study is also a validation of AECA's indicators at the Eurozone level providing new insights for further development of the IS taxonomy, which is on its way to gaining wider international acceptance. Our first recommendation refers to the consideration of new key performance indicators based on the fourth version of GRI guidelines, G4, which was launched in May 2013. Although the GRI still recognize reports based on G3, G3.1 versions, reports published after 31 December 2015 should be prepared in accordance with G4 guidelines. Among the objectives of the new version is, for example, the harmonisation with other reporting standards. Thus, G4 offers guidance on how to link sustainability reporting and integrated reporting, aligned with the IIRC. Furthermore, there are new and revised disclosures related to supply chain (disclosure including practice, screening, assessment and remediation) together with the value-chain materiality assessment describing the company's impact throughout the entire value chain. Stricter governance and remuneration disclosure are also required through new indicators such as: the ratio of executive compensation to median compensation, the ratio of executive compensation to lowest compensation, or the ratio of executive compensation increase to median compensation. Other new disclosure requirements refer to ethics and integrity, anti-corruption and public policy, and emissions and energy.

The current version and intention of IIRC and its effort regarding the harmonisation with other reporting standards (such as GRI) is already a big step forward for sustainability reporting. However, the product of IIRC, IR itself, has indeed much bigger potential. Although the narrative explanation on how a company creates and sustains value is important, it should be connected to quantitative disclosure as well.

Regarding the comparability, the integrated report will clearly vary from one company to another as each company will describe its own unique value creation story differently. But to enhance comparability, data disclosed in IR could be provided in a standardized digital file (XBRL) based on electronic tags for each individual item of data. Additionally, these specific XBRL tags should be embedded into the IR. This way, an automated processing of KPIs by computer software will be enabled (helping also to decrease the complexity of information) and narrative explanation of a quantitative item will be provided within the text in IR.

Our second recommendation refers to build some kind of Integrated Reporting navigation chart combining already existing XBRL elements with hyperlinks to all digital objects such as pdf files containing financial and sustainability reports, Youtube videos and social media channels providing details and a wider context of reported information. This way, the standardized XBRL data could effectively connect narrative explanation regarding the environmental, social, and governance performance with the quantitative data. Thus, applying the embedded XBRL taxonomy would enable better comparison and interchange of corporate data as well as seeing the evolution and possible impacts of reported KPIs in a wider context of sustainability. The navigation chart would also allow the connection of information into a coherent and integrated whole, which is one of the most important principles of IR. Having only quantitative KPIs does not completely explain the business model of the company and how corporate strategy affects corporate performance and corporate value.

Another practical implication is highlighting the scarcity of reporting on social indicators by Eurozone companies due to the lack of regulations in this area, which might be the reason why companies are less willing to report on them in comparison with environmental and governance indicators. Based on the existing regulation already adopted by some of the Eurozone countries on governance and environmental issues, we can have quite a good picture about companies’ actions in these areas. However, due to the lack of regulation regarding the reporting on social indicators such as non-compliance with legal regulations concerning customers, locally based suppliers, certified suppliers, and payment period to suppliers, we are omitting an extremely important part, a social aspect, in terms of sustainable development of our society. Hence, offering the results of our study, we would like to highlight the importance of regulation in the area of reporting on social indicators related not only to employees, but also to customers and suppliers.

Our results open up new avenues for future research. We analysed the extent of CSR reporting on the international level focusing on Eurozone companies. Therefore, further study might be extended to consider also the other economic areas. An interesting line of research could be to map the evolution of the CSR disclosure in those countries. Additionally, further study might check other factors that could have an impact on the extent of reporting (ROA, ROE, free float, etc.), while adopting more advanced statistical method. Even though more studies have examined whether investors attribute a significant value to the information provided in CSR reports, Wahba (2008) concludes that the value of CSR disclosure has not yet been investigated properly, and it is not clear how the reporting on CSR issues affects the firm value (measuring the stock price or price to book ratio). Therefore, we believe that it is important to analyse whether the efforts made by companies to report on their CSR practices are appreciated by investors or not.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare not to have any conflict of interest.

Differences between GRI and AECA's framework

| GRI | AECA |

|---|---|

| Economic indicators (9) | Economic indicators (9) |

| Categories | Categories |

| Economic performance | Economic performance |

| Market presence | |

| Indirect economic impact | |

| Environmental indicators (30) | Environmental indicators (5) |

| Categories | Categories |

| Materials | Energy efficiency |

| Energy | Pollution reduction |

| Water | Waste reduction |

| Biodiversity | |

| Emissions | |

| Effluents | |

| Waste | |

| Products and services | |

| Compliance | |

| Social indicators (45) | Social indicators (13) |

| Categories | Categories |

| Labour practices and decent work | Increase in human capital |

| Human rights | Increase in social capital |

| Society | |

| Product responsibility | |

| Corporate governance indicators (0) | Corporate governance indicators (8) |

| – | Categories |

| – | Corporate governance |