Since 2005, Portuguese listed companies have experienced an important institutional change, the mandatory adoption of new accounting standards (IFRS/IAS). European Union Regulation 1606/2002 made compliance with IFRS mandatory for the consolidated accounts of companies with securities traded on a regulated market. Existing literature suggests that accounting standards and country-specific characteristics affect the level of earnings management.

ObjectivesTherefore, the purpose of this paper is to analyze how accounting standards and the mandatory adoption of IFRS/IAS affect earning management in Portuguese listed companies.

MethodsIn order to do this, the paper analyze the evidence of earnings management, measured through discretionary accruals, after the adoption of IAS/IFRS by non-financial listed companies on Euronext Lisbon in the period 2005–2015. The Dechow et al. (2003) econometric model will be used, and empirical results indicate that non-financial listed companies in Portuguese stock exchange in the period 2005–2015 show evidence of discretionary accruals as a proxy for earnings management.

ResultsThus, the results suggest that after the adoption of IAS/IFRS there are still indications of earnings management in non-financial listed companies.

ConclusionsThis research will achieve two distinct contributions. First, filling a gap at the national level, given that there was no such study, that considered the analyzed period, and second, the enrichment of the literature on this subject, since it shows that in a country of continental Europe after the mandatory adoption of IFRS earning management continues to exist.

Desde 2005, las sociedades portuguesas que cotizan en bolsa han experimentado un importante cambio institucional: la adopción obligatoria de nuevas normas contables (IAS/IFRS). El Reglamento 1606/2002 de la Unión Europea establece que el cumplimiento de las nuevas normas es obligatorio para las cuentas consolidadas de las empresas con valores que cotizan en un mercado regulado. La bibliografía existente evidencia que las normas contables y las características específicas de cada país afectan al nivel de manipulación contable.

ObjetivosPor tanto, el propósito de este artículo es analizar cómo las normas de contabilidad y la adopción obligatoria de las IFRS afectan a la manipulación contable en las empresas portuguesas que cotizan en bolsa.

MétodosPara ello, se analiza la evidencia de la manipulación contable, medida a través de devengos discrecionales, tras la adopción de las IAS/IFRS por empresas no financieras que cotizan en Euronext de Lisboa en el período 2005-2015. El modelo econométrico de Dechow et al. (2003) y los resultados empíricos obtenidos indican que las empresas no financieras que cotizaban en la bolsa de valores portuguesa en el período 2005-2015 mostraban evidencia de devengos discrecionales como indicador de manipulación contable.

ResultadosPor tanto, los resultados muestran que después de la adopción de las IAS/IFRS todavía hay indicios de manipulación contable en las empresas no financieras que cotizan en bolsa.

ConclusionesEsta investigación logrará 2 contribuciones distintas: en primer lugar, cubrir una brecha a nivel nacional, dado que no existe ningún estudio que considere el período analizado, y segundo, permitir el enriquecimiento de la bibliografía sobre este tema, ya que muestra que en un país de Europa continental, después de la adopción obligatoria de las normas internacionales, continúan existiendo prácticas de manipulación contable.

Due to the consecutive financial scandals in the early twenty-first century in the United States (Enron, Xerox, WorldCom and Adelphia) and Europe (Parmalat and Ahold) we have become aware that the information disclosed by companies might not represent their true reality, thus tainting investors’ confidence in the information disclosed by companies and therefore in the financial markets (Jain & Rezaee, 2006).

These scandals, which shook Wall Street and had its origins in accounting tricks or simply incorrect practices, were only possible due to the complicity of several parties, showed that the instruments intended to supervise and monitor managers are not fully effective (Jain & Rezaee, 2006; Jensen, 2005).

In the European Union (EU) the effects of mandatory IFRS adoption are also an important topic (Alves & Antunes, 2010, 2011), however the impact of IFRS has remained controversial since its implementation, especially since the financial crisis (ICAEW, 2015). In this context, the study of issues such as earning managements becomes relevant.

The literature shows that the problem of earning management has been worrying researchers for several decades, and currently there are several lines of research in this field, developed mainly in the Anglo-Saxon countries (Mendes & Rodrigues, 2006). While the phenomenon of earnings management is widespread and widely discussed in the literature, in continental Europe it is a less developed theme when compared with the U.S., Canada, Australia and the UK.

In the last decade studies that have been made analyze the incentives for management (that literature relates to capital market pressures, compensation plans for managers, tax savings and the political costs) in the context of continental European countries (Baralexis, 2004; Coppens & Peek, 2005; Othman & Zeghal, 2006). These studies have contributed to understand the nature, purpose and implications of earnings management.

Earnings management may be acceptable by the flexibility of accounting rules allowing the adoption of accounting policies that permit managers to anticipate or defer the results in the desired direction, not violating accounting rules.

Some Portuguese researchers (Mendes & Rodrigues, 2006, 2007; Mendes, Rodrigues, & Esteban, 2012; Moreira, 2006a, 2006b) have already studied this problem, but there is still a long way to go in the investigation of this topic.

On the other side, Portuguese listed companies recently experienced an important institutional change, the mandatory adoption of new accounting standards (IFRS/IAS). Usually, accounting regulators such as the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB), attempt to increase the compatibility and value relevance of earnings information by developing an internationally acceptable set of accounting and financial reporting standards (Barth, Landsman, & Lang, 2008; Zhang, Uchida, & Bu, 2013). International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS/IAS), which has been adopted by numerous countries during the past two decades, is representative of such accounting standards. Consequently, the introduction of IFRS/IAS in 2005 provides us with an appropriate opportunity to examine whether accounting standards significantly affect the level of earnings management in Portuguese listed companies.

The effects of IFRS adoption on earning management are mixed. All around the world, some studies reports evidence supporting the claims of a positive impact (Ahmed, Chalmers, & Khlif, 2013; Chua, Cheong, & Gould, 2012; Iatridis, 2010; Iatridis & Rouvolis, 2010; Liu, Yao, Hu, & Liu, 2011; Zéghal, Chtourou, & Sellami, 2011). Others suggest a negative impact (Lin, Riccardi, & Wang, 2012; Paananen & Lin, 2009) or a no effect of IFRS adoption (Hung & Subramanyam, 2007; Tendeloo & Vanstraelen, 2005; Wang & Campbell, 2012).

Regarding the impact of IFRS adoption on earning management, the literature review carried out suggest that in countries like Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and Italy, firms were allowed to use IFRS and/or national GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) before 2005 and studies that analyze the impact of IFRS adoption on earnings management levels have been made (Barth et al., 2008; Gassen & Sellhorn, 2006; Goncharov & Zimmermann, 2006; Tendeloo & Vanstraelen, 2005). Nevertheless, the existing literature shows no consensus on the effects of (voluntary) adoption of the IAS/IFRS. Some authors argue that it caused a decrease in the level of discretionary accruals (Barth et al., 2008), but other studies show no change (Goncharov & Zimmermann, 2006) or the increasing of the level of discretionary accruals (Jeanjean & Stolowy, 2008; Tendeloo & Vanstraelen, 2005). On the other hand, many studies are based exclusively on adoption of IFRS on a voluntary basis, and only a few studies measure the impact of the regime transition, after the mandatory application of IFRS (Fernandes, 2007).1

The aim of this investigation is whether after the mandatory adoption of IAS/IFRS non-financial companies manipulate accounting results, measured through discretionary accruals. Moreover, the research question is: do listed nonfinancial companies in the Euronext Lisbon evidence accrual-based earnings management practices, after the adoption of IFRS?

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews the previous research on earnings management literature: approaches, concept, methods and measurement. This section is followed by a description of the methodology, research design and sample techniques employed in the study. Data analysis and results are reported in the subsequent section. Finally, concluding thoughts, limitations, implications and extensions for future research are presented.

Literature reviewTheoretical approachesThe concept of earnings management is supported by the idea that managers can alter the results to be reported (using different degrees of freedom in financial reporting or choosing or not to conduct transactions) and modify the stakeholders perception of results (Prencipe, Markarian, & Pozza, 2008). Therefore, and assuming that managers can change that perception, it is important to inquire about the reasons that lead managers to carry out this practice.

In recent years, there has been a lot of empirical research regarding the motivations behind earnings management (Kanagaretnam, Lobo, & Yang, 2004; Prencipe et al., 2008). According to Dechow, Sloan, and Sweeney (1996), there are two distinct points of view. One of them concerns academic research, which has focused on various contracting theories of earnings management and from which the ‘bonus hypothesis’ and the ‘debt hypothesis’ stand out. The other, emphasized by practitioners, relates to the role of accounting information in stockholders and creditors investment and lending decisions. As a result, two types of market imperfections, asymmetry of information and agency conflicts, support the existence of earning management.

However, the existing literature is not consensual. Beneish (2001) states that, if on the one hand, there is some scope for interpretation of earnings management as a way of signaling due to contractual incentives, on the other hand these incentives lead to opportunistic behaviors.

Thus, Beneish (2001) present two explanatory theories (approaches) of earnings management:

- (1)

The opportunistic approach: This approach lies in agency theory and believes that the subjectivity used by managers is disadvantageous, since earnings management leads to an inefficient allocation of resources and a change in the investors’ expectations regarding the company's future cash flows. Teoh, Welch, and Wong (1998), among others, fall into this approach and their results support the agency theory. Here, managers seek to mislead investors, distorting the financial information disclosed, i.e., managers materially alter the financial information that is provided, which damages investor's perception. Specifically, managers take advantage of information asymmetry between outsiders and themselves to maximize their utility in dealing with bonus plans, debt covenants and regulations.

- (2)

The informative approach: This approach, based on the signaling theory, argues that subjectivity is beneficial since it conveys to the market credible information not known by stakeholders, reducing information asymmetry. In other words, earning management is a powerful signaling mechanism through which inside information can reach the stockholders and the public (Jiraporn, Miller, Yoon, & Kim, 2008). Some authors (Arya, Glover, & Sunder, 2003; Guttman, Kadan, & Kandel, 2006; Healy & Palepu, 1993; Subramanyam, 1996; Tucker & Zarowin, 2006) have used this perspective. Managers introduce their own expectations about future cash flows in the financial reports, providing investors with greater information content.

The literature revealed that the majority of earnings management studies focused on the opportunistic approach both in the international (Beneish, 2001; Fonseca & González, 2008) and national context (Borralho, 2007; Fernandes, 2007; Santos, 2008).

According to the literature managers exercise accounting discretion to maximize their compensation (e.g. Healy & Palepu, 2001), and such opportunistic behavior increase the firm's agency costs (Francis, Olsson, & Schipper, 2005). It seems that the firm's agency costs are directly correlated to the amount of discretion in the selection of the firm's accounting procedures. However, the literature does also describe some cases in which granting management with increased accounting discretion, proved to moderate the firm's agency cost (Adut, Holder, & Robin, 2013). Here, predictable earnings can lower a firm's information risk, which can also lower the firm's costs (Kravet & Shevlin, 2010).

However, using accruals quality as the proxy for information risk, Francis et al. (2005) suggest the existence of some heterogeneity in managers’ behavior. “While many managers use discretionary accruals to improve the reporting quality (decreasing information uncertainty), previous research on earnings management has also documented how managers, in some time periods, make accounting choices that reduce accruals quality (increasing information uncertainty)” (Francis et al., 2005:324). And information risk increase when investors are concerned with managers’ discretionary accounting choices (Kravet & Shevlin, 2010).

Earnings managementIn the accounting literature, there is not a consensual definition regarding the manipulation of accounts and, different expressions are used to describe the same phenomenon such as earnings management and creative accounting. In this paper, we use the term earnings management to designate all forms of manipulation, with the exception of financial reporting fraud.

It is therefore considered that earnings management is the management intervention in the production process and reporting of accounting information in order to obtain certain self-benefits. The manipulation may further comprise the actual manipulation, in the sense that the manipulation of the results may result from the choice of the right moment for making funding or investments decisions (Schipper, 1989).

Accordingly, to Healy and Wahlen (1999) the phenomenon of earnings management occurs when managers use their own judgment in a discretionary manner, in the preparation of financial reporting and in the completion of certain transactions, with the objective of influencing stakeholders. When they try to adjust the values of certain accounts in order to comply with requirements imposed by contracts based on accounting data. A recent study (Halaoua, Hamdi, & Mejri, 2017) suggests that French and British firms manage their earnings in order to avoid losses, and decreases in earnings.

Ronen and Yaari (2008) classify earnings management in three distinct groups:

- (1)

White – White earnings management (beneficial) enhances the transparency of reports.

- (2)

Gray – Managing reports within the boundaries of compliance with bright-line standards (gray), which could be either opportunistic or efficiency enhancing (Ronen & Yaari, 2008).

- (3)

Black – Black earnings management involves absolute misrepresentation. It assumes practices intended to misrepresent or reduce transparency in financial statements.

Ronen and Yaari (2008) see as examples of a negative (black) earnings management definition the ones sustained by Schipper (1989) and Healy and Wahlen (1999). Ronen and Yaari (2008) see this last one as the one that best describes the manipulation of results. “Earning management occurs when management uses judgment in financial reporting and in structuring transactions to alter financial reports to either mislead some stakeholders about the underlying economic performance of the company or to influence contractual outcomes that depend on reported accounting numbers”(Healy & Wahlen, 1999:368).

It has to be noted that all three definitions are within the boundaries of the rules and regulations.

Earnings management comprises practices within the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and practices that do not follow the GAAP (e.g. reservations by disagreement of the external auditor) whose goal is to distort materially the financial statements (Bedard & Johnstone, 2004). Regarding the use of flexibility in accounting standards, it is considered earnings management only if the intention is there (Dechow & Skinner, 2000; Dechow et al., 1996). If managers use the flexibility of accounting standards with the goal of making financial statements more informative for users by providing a truer picture of the situation of the company, then the situation is not understood as earnings management (Beneish, 2001; Healy & Wahlen, 1999; Schipper, 1989).

In theory it seems easy to distinguish earnings management, but in fact, it is difficult because there are accounting transactions considered to be in the limit (gray areas), where the ethical factor and value judgments are decisive in the decision to be taken.

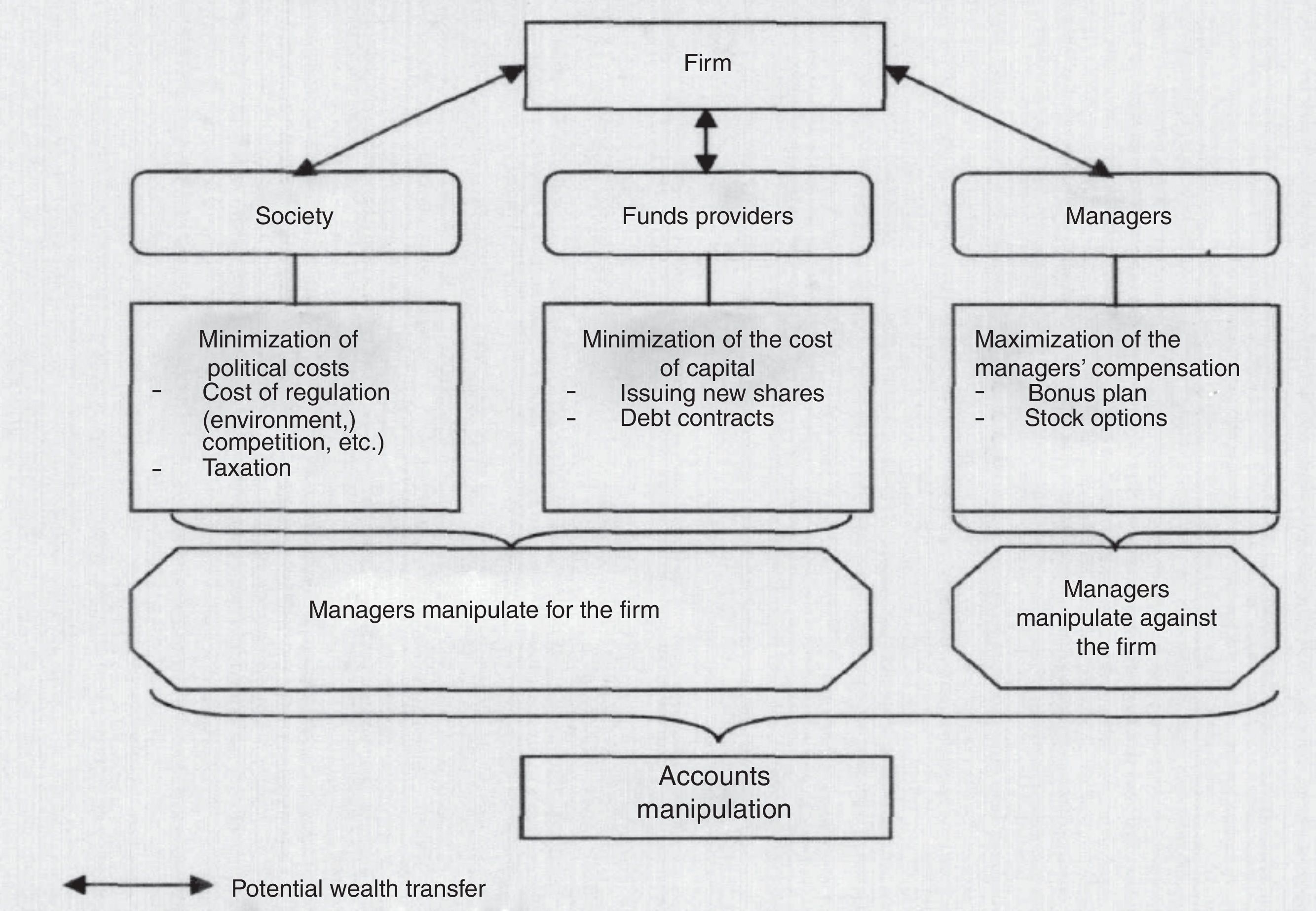

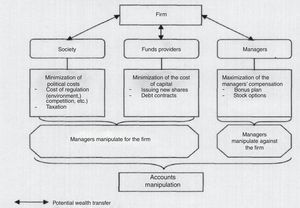

Managers manipulate in order to avoid costs or give certain benefits to the company itself and/or to secure benefits for themselves. According to Stolowy and Breton (2004), earnings management has the effect of modifying the allocation of wealth (see Fig. 1) generated between the company and society (political costs), capital providers (capital costs) and managers (compensation plans). Changing the allocation of wealth, instigated by different incentives to manipulation, can be obtained in order to create benefits for the company or benefits to other agents, such as managers (Stolowy & Breton, 2004).

Earnings management methodsGenerally, literature states two methods to apply earnings management: accrual management and real transactions. Accrual management occurs because there is sufficient flexibility in accounting standards to allow managers to make choices in accounting policies and accounting methods, in the accounting estimates and judgments, and in the record of realities that could have an accounting translation (recognition and measurement). Here, we can include the misapplication of accounting principles such as materiality, conservatism and matching principle; changes in the accounting methods; as well as in the classification of gains and extraordinary losses. The existing flexibility in financial reporting, namely the discretionary power that can be exerted over accruals, can serve to provide information on the real economic prospects of the company, reducing the information asymmetry between “internal” and “external” and thus adding value to the financial reporting (Schipper, 1989; Subramanyam, 1996).

The second method means that managers are manipulating reported earnings by structuring real transactions. They can alter the timing and scale of real activities throughout the accounting period in such a way that a specific earnings target could be met. This method is also named natural income manipulation, i.e., playing with the timing of transactions (Stolowy & Breton, 2004). The real decisions relate mainly to the choice of timing for making investments and/or financing.

The elimination of judgments and estimates does not represent the best way to improve the financial reporting system (Parfet, 2000). The elimination of the flexibility of the rules is not advisable, or even possible; however, unlimited flexibility is also not practicable given the need for some degree of certainty and safety (Healy & Wahlen, 1999).

The income manipulation tends to occur in accounting estimates such as depreciation, provisions and adjustments (impairment losses), in the accounting inventory methods (first in, first out method, weighted average method, …) and methods of assets depreciation (straight-line depreciation and declining balance). Although earnings management can also be practiced by changing accounting policies, this practice is less used by managers due to the obligation of disclosure in the financial statements (Osma & Noguer, 2005).

In Portugal, the existing flexibility in accounting standards is hardly used for manipulation purposes. The close relationship between accounting and taxation makes professionals avoid situations, which give rise to corrections in the declaration of revenues (IRC Model 22). To avoid these situations, companies tend to follow closely the tax-imposed criteria. However, the tax policy encourages the income manipulation in some situations. For example, Marques, Rodrigues, and Craig (2011) evaluated the extent to which the tax policy “special on account payment” encourages the Portuguese companies to manipulate the results. They have concluded that companies with higher tax rates reduce the results to near zero, i.e., firms with tax rates on higher average income are more likely to develop practices of earnings management than other firms.

The accounting standards flexibility allows that managers develop most practices of earnings management, through decisions that do not generate impacts on cash flows, being this modality less expensive than hiring the services of a professional. Several studies demonstrate this behavior at the level of adjustments for doubtful debts (McNichols & Wilson, 1988); by changing the cost formulas for inventories (Sweeney, 1994); by changing the amortization methods (Keating & Zimmerman, 2000; Sweeney, 1994); by changing the estimated useful lives of the assets (Keating & Zimmerman, 2000); through assets and deferred tax liabilities (Phillips, Pincus, & Rego, 2003).

Real activities manipulation consists of managers actions that divert the company from its normal course of operational practices, to reach a certain level of results. Thus, stakeholders are induced to accept that level of income as the normal result of business (Roychowdhury, 2006).

In a long-term perspective, these actions do not always contribute to the increased value of the company as it may have a negative effect on cash flows of future periods. As an example, overproduction generates excess inventory in stock, which must be sold in future periods. Although a flow of funds can be expected, the company assumes, during a certain period, an increase in storage costs (Roychowdhury, 2006).

In some situations managers prefers real activities manipulation, because it is unlikely that auditors discuss with managers certain issues, for example, the research and development investment policy. So, manipulation through real activities is used when significant differences exist between the results of pre-manipulation and the desired results, bearing in mind that the last ones might not be achieved with the use of estimates and/or changes in accounting policies (Roychowdhury, 2006).

In the literature, the following methods of real activities manipulation were identified (Dechow & Skinner, 2000; Gunny, 2005; Healy & Wahlen, 1999; Roychowdhury, 2006; Zang, 2007):

- (1)

Reduction of expenses on research and development and/or advertising, transferring the allocation of resources to subsequent periods.

- (2)

Increased sales by giving larger discounts or more favorable credit conditions (this situation generates higher cash flows that will be reduced when the company restores its activity). Other practices are to increase significantly the volume of sales at the end of a certain year, at the beginning of the following year, if it accepts its return by the customers. In both cases, these situations fall within the boundary that divides the normal earnings management from the company normal business management.

- (3)

Increased production exceeds demand (production to stock), leading to a lower unit cost (fixed costs spread over more units) which in turn leads to the reporting of higher operating margins on sales already made.

The existence of these methods has been studied in several works. For example, Roychowdhury (2006) investigated whether firms make operational decisions related to sales, production levels and discretionary spending to avoid reporting losses and thus manipulate accounting information. Gunny (2005) studied the future consequences of operational decisions associated with the manipulation of accounting results; i.e., he examined whether these decisions affect the company's ability to generate cash flows and profit in the future. Zang (2007) resorted to cost-benefit analysis to see if firms with more rigid accounting take more operational decisions handling the accounting information, than the remaining companies.

Earnings management measurementIn the earnings management literature, several authors have used different methods in order to understand the reasons why managers manipulate; how they do it and, which consequences have those actions. However, identify and measure the results of the firms earnings management is a complicated task. It is difficult to recognize whether or not the company violates GAAP, by practicing an aggressive or conservative accounting (Dechow & Skinner, 2000; Vinciguerra & O’Reilly-Allen, 2004). Many accounting choices are on the border of manipulation of the results. However, to identify the manipulation several authors have indicated the intent of the executive to disguise the real economic performance of companies and the use of discretion over the accounts to act opportunistically expropriating shareholders (Healy & Wahlen, 1999). However, companies have certain flexibility in the application of accounting standards, which is likely to lead to manipulation of results, via the accruals to recognize in each accounting period.

Despite the fact that manipulation of results may occur through changes in accounting policies, the literature is unanimous in stating that managers, given the mandatory disclosure of financial statements, rarely use this practice (Osma & Noguer, 2005).

The limited flexibility of the normative regarding cash flows makes the handling of this part of the results more difficult, expensive, and easily detectable. Therefore, and although there are studies that investigated the results manipulation analyzing the cash flows (Roychowdhury, 2006), the literature has focused on the analysis of the accruals component, since it is here that there is a greater possibility of manipulation (e.g. accounting methods, assumptions and estimates).

Earnings management is usually examined using discretionary accruals (Ahmed et al., 2013), specific accruals (Dechow, Ge, & Schrand, 2010), earnings smoothing (Ahmed et al., 2013; Barth et al., 2008) or positive earnings threshold (Barth et al., 2008; Gilliam, Heflin, & Jeffrey, 2015). And, there are several authors who consider that discretionary accruals manipulation is the most common form of manipulation because it is less expensive, more difficult to be detected by the market (Healy & Palepu, 1993; Watts & Zimmerman, 1990) and more difficult to audit, given the subjective nature of the judgments involved (Spathis, Doumpos, & Zopounidis, 2002).

Studies seeking to detect evidence of manipulation, whether within specific studies of earnings management (e.g. Jones, 1991), or studying the quality of results (e.g. Burgstahler, Hail, & Leuz, 2006), do it, usually through the analysis of accruals. In this research line, several authors (Bartov, Gul, & Tsui, 2001; Bowman & Navissi, 2003; Dechow, Sloan, & Sweeney, 1995; Jones, 1991) suggest the use of discretionary accruals as an indicator of earnings management.

The model of Jones (1991) and the modified version proposed by Dechow et al. (1995) have been the most used in the literature that uses the aggregate accruals. This model is able to decompose accruals into discretionary and non-discretionary accruals. According to Xiong (2006), the modified Jones model controls the changes in the economic transactions environment and the credit policies for sales. However, as in the Jones model (1991), we cannot guarantee that all economic conditions are captured by the explanatory variables. The modified Jones model has been one of the most widely used models in the calculation of discretionary accruals (Bartov et al., 2001; Becker, DeFond, Jiambalvo, & Subramanyam, 1998; Davidson, Stewart, & Kent, 2005; DeFond & Subramanyam, 1998; Osma & Noguer, 2005), but some criticism has emerged recently (Ball & Shivakumar, 2006; Moreira & Pope, 2007).

Although several models based on accruals had been developed, detection of earnings management continues to be based largely on the solution initially proposed by Jones (1991), which was subject to subsequent adjustments with the emergence of the modified-Jones model (Dechow et al., 1995) and other variants (e.g. Dechow et al., 2003).

Jacksonh and Pitman (2001) argue that omissions in Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) provide a degree of discretion for the executive to act opportunistically and intentionally in the distortion of the accounting and financial information presented in the financial statements. One way to measure the effects of opportunistic behavior of executives in accounting decisions is through discretionary accruals (Nelson, Elliott, & Tarpley, 2002), which are considered as proxies to measure the manipulation of results. Hence, it is difficult to identify potential handling practices resulting from the application of GAAP, using statistical models and accounting information ex-post (Dechow & Skinner, 2000; Healy & Wahlen, 1999).

Methodology, research design and sampleMethodologyQuantitative research in accounting as in other fields of knowledge includes planning, sample selection, data collection and analysis methods. This research process is influenced by three sequential factors: ontology, epistemology and methodology (Chua, 1986). The research methodology depends on the phenomenon to study (Ryan, Scapens, & Theobald, 2002).

Ontology is formed by the philosophical assumptions of the researcher about the nature of reality; i.e., it addresses the way the researcher sees reality (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, & Jackson, 2008). Epistemology are the assumptions of the researcher on the best ways to investigate the nature of the world and the establishment of “truth”, i.e., it deals with the question of the construction of scientific knowledge (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008).

Researchers classify accounting research in three paradigms (Baxter & Chua, 2003): (1) positivist research – mainstream in accounting (2) interpretive research and (3) critical analysis. We chose positivist research by considering the type of evidence to be obtained is reconcilable with an objective conception of reality (Bhimani, 2002; Chua, 1986), considering it as something external to the researcher, and the existence of a logic of rationality in the decision supported by the accounting information (Bhimani, 2002), characteristics of the paradigm of positivistic research (Chua, 1986).

The positivist research looks at reality as objective and independent of the investigator (Ahrens & Chapman, 2006; Chua, 1986; Hopper & Powell, 1985; Ryan et al., 2002). According to Chua (1986), the positivist paradigm is characterized by the fact that the observation of phenomena is separated from theory and it can be used to validate it.

In epistemological terms, positivism professes that knowledge comes from observation and generalization of observed phenomena, using quantitative methods that relate dependent and independent variables to test previously established hypotheses (Ahrens & Chapman, 2006; Ryan et al., 2002). The positivist methodology is based on a hypothetical-deductive process to explain causal relationships (Chua, 1986; Ryan et al., 2002).

To some authors (e.g. Vieira, 2009) the problem of positivist research is in its assumptions. However, positivists have challenged the various criticisms, stating that the realism of assumptions is irrelevant from a theoretical approach. The quality of the theory depends on its ability to predict phenomena and generate hypotheses to be tested later (Ryan et al., 2002; Wickramasinghe & Alawattage, 2007).

Research designOur sample firms consist of Portuguese non-financial companies listed on the Euronext Lisbon stock Exchange from 2005 through 2015. The final sample consists of 533 firm-years observations over the sample period. All are large or medium-sized companies of five different sectors: Materials, Industry and Construction; Oil and Energy; Consumer Services; Consumer Goods; Technology and Communication. The choice of the Portuguese non-financial companies listed on the Euronext Lisbon was due to the following facts: They have adopted compulsory the IAS/IFRS. Chand (2005) and Alp and Ustundag (2009) have proved the existence of challenges in the implementation of IAS/IFRS by European companies. The challenges not only occurred during the period of national adaptation to EU policies but also during the implementation of this legislation. A major obstacle to European accounting harmonization lies in the differences between the accounting practices of member countries, which make the implementation of IFRS an extremely complex process (Fontes, Rodrigues, & Craig, 2005; Rodrigues & Craig, 2006).

Corporate financial data are obtained from the CMVM (Comissão do Mercado e de Valores Mobiliários).

Below, we will describe the various steps of the research.

Objective: To establish the existence of evidence of earning management practices.

Step 1: we conducted research in the bulletins of Euronext Lisbon and in the CMVM website (annual accounts) to identify non-financial listed companies.

Step 2: we collected on the CMVM website the reports and accounts of companies and we performed the analysis of these reports.

Step 3: we tested the modified-Jones Model (2003).

Step 4: we inferred about the existence of evidence of earning management practices.

In the selection of the population for the year 2005, we based our studies in the Euronext Lisbon Daily Bulletin (Official Market Quotations) and the CMVM (annual financial statements and studies: Audit Reports of the companies with securities listed on December 31st, 2005). Subsequently, we consulted the Euronext Lisbon Daily Bulletin (Official Market Quotations) and the CMVM financial statements and included the companies admitted to listing. Between 2011 and 2015, non-financial companies listed in 2011 were considered for analysis purposes.

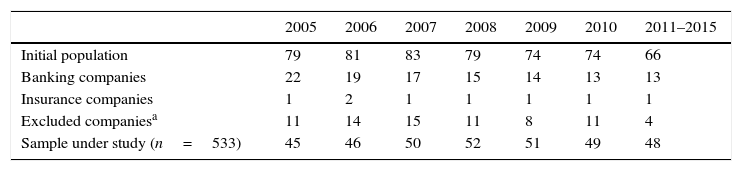

The following table (Table 1) summarizes the construction of the study sample used to estimate the model.

Study sample.

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011–2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial population | 79 | 81 | 83 | 79 | 74 | 74 | 66 |

| Banking companies | 22 | 19 | 17 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 13 |

| Insurance companies | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Excluded companiesa | 11 | 14 | 15 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 4 |

| Sample under study (n=533) | 45 | 46 | 50 | 52 | 51 | 49 | 48 |

Financial companies were excluded due to their accounting specificities. According to Ruiz-Barbadillo, Gómez-Aguilar, Fuentes-Barberá, and García-Benau (2004) the interpretation of financial ratios differs significantly from the rest of the companies (non-financial), and it may change the interpretation of the results. Therefore, we eliminated companies in the financial sector due to the structure of working capital (Klein, 2002) and, because there are differences in the process of formation of accruals (Osma & Noguer, 2005). As with other studies, we have excluded financial firms and insurance companies due to the specific rules to which they are subjected (Becker et al., 1998; Kim, Chung, & Firth, 2003; Myers, Myers, & Omer, 2003).

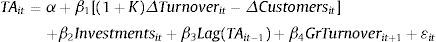

Based on the modified-Jones model (Dechow et al., 2003) we have replaced the sales turnover in order to study all the companies in the study population (some companies only provide services). We also proceeded to the replacement of fixed assets for investments (investment properties, tangible fixed assets and intangible assets) given the impact they have on operating income through depreciation, amortization and impairment losses. The variables are deflated by total assets at the end of the year to reduce heteroscedasticity and to allow comparisons between companies.

Following, we present the model already with changes:

(MODEL 1)What:

- •

TAit: total accruals of firm i in period t, deflated by total assets at the end of the period t.

- •

Turnoverit: Variation of the turnover of firm i of period t−1 for period t, deflated by total assets at the end of the period t.

- •

Customers Δ: variation of customers’ accounts of firm i of period t−1 for period t, deflated by total assets at the end of the period t.

- •

Investmentsit: account balances of Tangible Fixed Assets, Intangible Assets and Properties Investment firm i at the end of the period t, deflated by total assets at the end of the period t.

- •

Lag (TAit−1): total accruals of firm i in period t−1, deflated by total assets at the end of the period t−1 (lagged total accruals).

- •

GrTurnoverit+1: growth of turnover in the next period, calculated by variation the turnover of firm i of period t to the period t+1, deflated by the turnover of firm i of the period t.

- •

k: correction factor, which captures the expected variations in customer accounts, due to the variation of the turnover of firm i of the period t−1 for the period t deflated by total assets at the end of the period t.

- •

¿it: regression error.

- •

α, β1, β2, β3 and β4: Estimated coefficients by equation.

The estimation of discretionary accruals in the Jones and Jones modified models is done in two phases:

- (1)

To be able to estimate discretionary accruals, it is necessary to calculate the total of accruals.Total accruals=Operating income−Operating Cash flows (Moreira, 2009).

- (2)

The Jones or the modified-Jones model measure non-discretionary accruals according to the level of property, plant and equipment (investment), variations in sales (turnover) and customers, for each sector of activity and for all years.As we have already seen, all variables are deflated by total assets at the end of the year2 to reduce heteroscedasticity and so that they can make comparisons between companies3.

Having adopted the modified-Jones model (Dechow et al., 2003) and deflating the same variables by total assets in the previous period (although previous research use the net assets of the previous year) we have chosen to use the asset value of the year as Gallén, Begoña, and Inchausti (2005), because we use consolidated accounts, which show significant variations in some situations, due to changes in the consolidation perimeter.

According to Moreira (2006b) manipulated results tend to leave traces in accounting. It seeks to detect evidence of this manipulation, through specific studies of earnings management (e.g. Jones, 1991) or studies of the quality of results (e.g. Burgstahler et al., 2006), using analysis of accruals. Thus, they disaggregate accruals into two components: a non-discretionary part (NDAC), which is assumed to be the level that the company would report if there was no manipulation and the discretionary part (DAC), obtained by difference from the total accruals, which corresponds to the measurement of the manipulation performed.

The accruals models are used to accomplish this breakdown, playing an important role in empirical research in accounting (Moreira, 2006a). Despite its limitations, the Jones model (1991) has had and continues to have relevance, being one of the most used in empirical research (Peasnell, Pope, & Young, 2000). Many alternative models are based on the Jones model, or reconciled with it (Moreira, 2006a). In short, the Jones models (Dechow et al., 1995; Jones, 1991) were and are widely used in research in accounting (Algharaballi & Albuloushi, 2008; Bergstresser & Philippon, 2006; Chen, Lin, & Zhou, 2005; Ecker, Francis, Olsson, & Schipper, 2013; Gore, Pope, & Singh, 2007; He, Yang, & Guan, 2010; Jones, Krishnan, & Meleudrez, 2008; Klein, 2002; Rusmin, 2010).

Data analysis and resultsThe application of the theoretical linear regression model (1) allowed us to estimate the value of discretionary accruals for each firm in the years 2005–2015, which is the main objective of its implementation.

Discretionary accruals were estimated from the values of errors and waste (εit) obtained from the application of the model itself which allowed us to identify evidence of earnings management in companies during the examined period. We consider that there is evidence of earnings management when the errors or residuals are different from zero, i.e., when there are discretionary accruals.

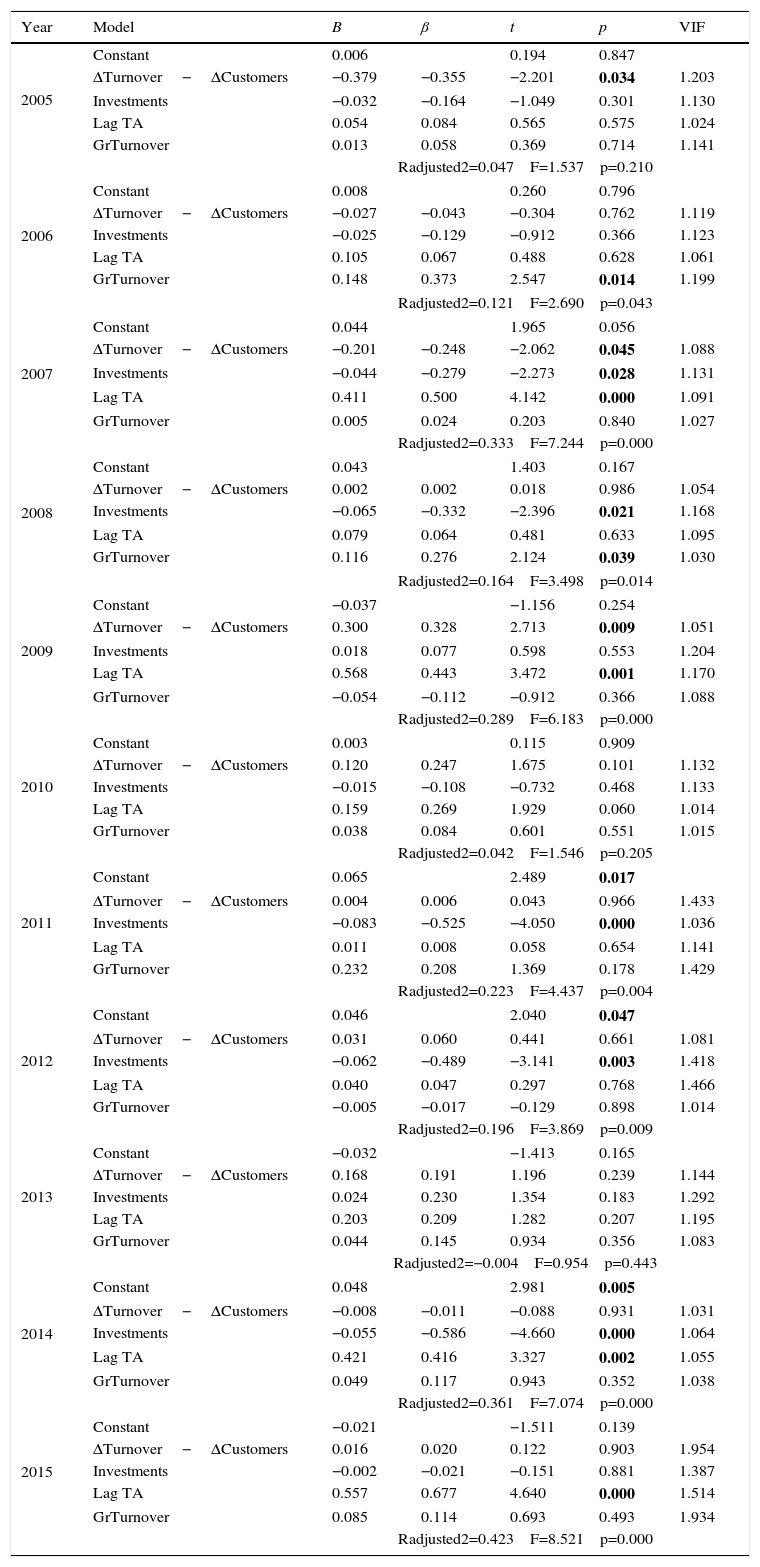

Analyzing the results in Table 2 we are allowed to verify that the model did not reveal itself statistically significant in 2005 (F=1.537, p=0.210), 2010 (F=1.546, p=0.205) and 2013 (F=0.954; p=0.443). The explanatory power of the model ranged from −0.4% in 2013 to 42.3% in 2015. The fact that the values of Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) being relatively low suggests the absence of multicollinearity problems among the variables in the model (Table 2).

Results of the model 1 for the years 2005–2015 (univariate linear regression).

| Year | Model | B | β | t | p | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Constant | 0.006 | 0.194 | 0.847 | ||

| ΔTurnover−ΔCustomers | −0.379 | −0.355 | −2.201 | 0.034 | 1.203 | |

| Investments | −0.032 | −0.164 | −1.049 | 0.301 | 1.130 | |

| Lag TA | 0.054 | 0.084 | 0.565 | 0.575 | 1.024 | |

| GrTurnover | 0.013 | 0.058 | 0.369 | 0.714 | 1.141 | |

| Radjusted2=0.047 F=1.537 p=0.210 | ||||||

| 2006 | Constant | 0.008 | 0.260 | 0.796 | ||

| ΔTurnover−ΔCustomers | −0.027 | −0.043 | −0.304 | 0.762 | 1.119 | |

| Investments | −0.025 | −0.129 | −0.912 | 0.366 | 1.123 | |

| Lag TA | 0.105 | 0.067 | 0.488 | 0.628 | 1.061 | |

| GrTurnover | 0.148 | 0.373 | 2.547 | 0.014 | 1.199 | |

| Radjusted2=0.121 F=2.690 p=0.043 | ||||||

| 2007 | Constant | 0.044 | 1.965 | 0.056 | ||

| ΔTurnover−ΔCustomers | −0.201 | −0.248 | −2.062 | 0.045 | 1.088 | |

| Investments | −0.044 | −0.279 | −2.273 | 0.028 | 1.131 | |

| Lag TA | 0.411 | 0.500 | 4.142 | 0.000 | 1.091 | |

| GrTurnover | 0.005 | 0.024 | 0.203 | 0.840 | 1.027 | |

| Radjusted2=0.333 F=7.244 p=0.000 | ||||||

| 2008 | Constant | 0.043 | 1.403 | 0.167 | ||

| ΔTurnover−ΔCustomers | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.018 | 0.986 | 1.054 | |

| Investments | −0.065 | −0.332 | −2.396 | 0.021 | 1.168 | |

| Lag TA | 0.079 | 0.064 | 0.481 | 0.633 | 1.095 | |

| GrTurnover | 0.116 | 0.276 | 2.124 | 0.039 | 1.030 | |

| Radjusted2=0.164 F=3.498 p=0.014 | ||||||

| 2009 | Constant | −0.037 | −1.156 | 0.254 | ||

| ΔTurnover−ΔCustomers | 0.300 | 0.328 | 2.713 | 0.009 | 1.051 | |

| Investments | 0.018 | 0.077 | 0.598 | 0.553 | 1.204 | |

| Lag TA | 0.568 | 0.443 | 3.472 | 0.001 | 1.170 | |

| GrTurnover | −0.054 | −0.112 | −0.912 | 0.366 | 1.088 | |

| Radjusted2=0.289 F=6.183 p=0.000 | ||||||

| 2010 | Constant | 0.003 | 0.115 | 0.909 | ||

| ΔTurnover−ΔCustomers | 0.120 | 0.247 | 1.675 | 0.101 | 1.132 | |

| Investments | −0.015 | −0.108 | −0.732 | 0.468 | 1.133 | |

| Lag TA | 0.159 | 0.269 | 1.929 | 0.060 | 1.014 | |

| GrTurnover | 0.038 | 0.084 | 0.601 | 0.551 | 1.015 | |

| Radjusted2=0.042 F=1.546 p=0.205 | ||||||

| 2011 | Constant | 0.065 | 2.489 | 0.017 | ||

| ΔTurnover−ΔCustomers | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.043 | 0.966 | 1.433 | |

| Investments | −0.083 | −0.525 | −4.050 | 0.000 | 1.036 | |

| Lag TA | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.058 | 0.654 | 1.141 | |

| GrTurnover | 0.232 | 0.208 | 1.369 | 0.178 | 1.429 | |

| Radjusted2=0.223 F=4.437 p=0.004 | ||||||

| 2012 | Constant | 0.046 | 2.040 | 0.047 | ||

| ΔTurnover−ΔCustomers | 0.031 | 0.060 | 0.441 | 0.661 | 1.081 | |

| Investments | −0.062 | −0.489 | −3.141 | 0.003 | 1.418 | |

| Lag TA | 0.040 | 0.047 | 0.297 | 0.768 | 1.466 | |

| GrTurnover | −0.005 | −0.017 | −0.129 | 0.898 | 1.014 | |

| Radjusted2=0.196 F=3.869 p=0.009 | ||||||

| 2013 | Constant | −0.032 | −1.413 | 0.165 | ||

| ΔTurnover−ΔCustomers | 0.168 | 0.191 | 1.196 | 0.239 | 1.144 | |

| Investments | 0.024 | 0.230 | 1.354 | 0.183 | 1.292 | |

| Lag TA | 0.203 | 0.209 | 1.282 | 0.207 | 1.195 | |

| GrTurnover | 0.044 | 0.145 | 0.934 | 0.356 | 1.083 | |

| Radjusted2=−0.004 F=0.954 p=0.443 | ||||||

| 2014 | Constant | 0.048 | 2.981 | 0.005 | ||

| ΔTurnover−ΔCustomers | −0.008 | −0.011 | −0.088 | 0.931 | 1.031 | |

| Investments | −0.055 | −0.586 | −4.660 | 0.000 | 1.064 | |

| Lag TA | 0.421 | 0.416 | 3.327 | 0.002 | 1.055 | |

| GrTurnover | 0.049 | 0.117 | 0.943 | 0.352 | 1.038 | |

| Radjusted2=0.361 F=7.074 p=0.000 | ||||||

| 2015 | Constant | −0.021 | −1.511 | 0.139 | ||

| ΔTurnover−ΔCustomers | 0.016 | 0.020 | 0.122 | 0.903 | 1.954 | |

| Investments | −0.002 | −0.021 | −0.151 | 0.881 | 1.387 | |

| Lag TA | 0.557 | 0.677 | 4.640 | 0.000 | 1.514 | |

| GrTurnover | 0.085 | 0.114 | 0.693 | 0.493 | 1.934 | |

| Radjusted2=0.423 F=8.521 p=0.000 | ||||||

The most relevant values that are explained in the text are highlighted in bold.

The residue analysis allowed us to validate the assumptions for the application of the linear regression model given that the errors have a normal distribution and have zero covariance, i.e., they evidence to be independent.

An overall assessment of the results of the standardized regression coefficients (β) allows us to state that the value of total accruals tends to increase with increasing lagged total accruals and with growth of the turnover and tend to move in opposite direction depending on the increase of the remaining variables.

Determining the statistical significance of the predictor variables and analyzing each of the years we found that, in 2005, only the variable “ΔTurnover−Δ Clients” shows a statistically significant predictor power and its increase tends to contribute to the reduction of total accruals (β=−0.355, p=0.034). In 2006, the only variable with predictive power is “CrTurnover”, an increased in its value contributes to the increase in total accruals (β=0.373, p=0.014). In 2007, the variables emerged as having predictor power, statistically significant, “ΔTurnover−Δ Clients” “Investment” and “Lag AT”. Increasing values of the first two tend to contribute to lower the total accruals (β=−0248, p=0.045 and β=0.279, p=0.028) while increasing the third variable tends to increase the values of total accruals (β=0.500, p=0.000). In 2008, emerged as predictors the “Investment” and “CrTurnover”. The increase of the former tends to contribute to the decrease in the value of total accruals but the increase of the values of the second tends to contribute to the increase of total accruals (β=−0332, p=0.021 and β=0.276, p=0.03). In 2009, “ΔTurnover−Δ Client” and “Lag AT” emerged as the predictor variables. The increase in the values of any of these variables tends to contribute to the increase of total accruals (β=0.328, p=0.009 and β=0.443, p=0.001).

In 2010, only the variable “Lag AT” showed a predictive power statistically significant at 10%, and the increase of the values of this variable tend to contribute to the increase in the values of total accruals (β=0.269, p=0.060). In 2011, only the variable “Investments” proved to be a significant predictor and the increase of values tends to contribute to the decrease in the value of total accruals (β=−0.525, p=0.000). In 2012, only the variable “Investments” proved to be a significant predictor and an increase of the values of this variable tends to contribute to the decrease in the value of total accruals (β=−0.489; p=0.003). In 2013, no variable showed a statistically significant predictive power. In 2014, the following variables appeared to have a statistically significant predictive power: “Investments” and “Lag TA”. An increase in the value of “Investments” tends to contribute to a decrease in the value of total accruals (β=−0.586; p=0.000). While the increase of the second variable “LagTA” tends to increase the values of the total accruals (β=0.416; p=0.002). Finally, in 2015, only the variable “Lag TA” proved to be a significant predictor and an increase in its value tends to contribute to the increase of total accruals (β=0.677; p=0.000).

The coefficient of determination (R2adjusted) ranged from −0.4% in 2013 to 42.3% in 2015. The test of the predictive ability of the models revealed that only in 2005 (F=1.537, p=0.210), 2010 (F=1.546, p=0.205) and 2013 (F=0.950; p=0.443) this ability was not statistically significant.

After presenting the results of model 1 we confronted these results with the literature.

Consistent with previous empirical evidence (Davidson et al., 2005; Dechow et al., 2003; Jones, 1991; Osma & Noguer, 2005; Peasnell et al., 2005), we found a positive coefficient on the explanatory variables involving sales (ΔTurnover−ΔClients) and a negative coefficient (2005–2008, 2010–2012 and 2014–2015) for the variable investments.

In the literature review it was found a lack of consensus on the effects of adoption (voluntary) of the IAS/IFRS, for some authors it caused a decrease in the level of discretionary accruals (Barth et al., 2008), but other studies show no change (Goncharov & Zimmermann, 2006) or the increasing of the level of discretionary accruals (Tendeloo & Vanstraelen, 2005). In this study, the model results allow us to conclude that there is evidence of earnings management in companies during the period analyzed.

The explanatory power of the model, given by R2adjusted, reveals low indicators during the period of 2005–2015, varying between −0.4% and 42.3%. It is found that −0.4% to 42.3% of the variation in total accruals is explained by the explanatory variables (not discretionary accruals) and the remaining is due to other not specified factors that are included in the random variable (discretionary accruals) (¿) (Pestana & Gageiro, 2008). These results allow us to conclude that there is evidence of earnings management in non-financial listed companies in the period 2005–2015.

The linear relationship between the dependent variable and the explanatory variables is statistically significant during the period, except in 2005, 2010 and 2013, i.e., the model proves to be adequate to describe the relationship (Pestana & Gageiro, 2008) in most of the period.

ConclusionsThis final section presents some reflection on the results of research undertaken especially in terms of their contributions to the improvement of theoretical knowledge and practical research. Some limitations and suggestions for future research are presented.

Motivated by the current debate regarding the adoption of IFRS, we recall that our research question was as follows: do nonfinancial companies listed in the Euronext Lisbon evidence accrual-based earnings management practices, after the adoption of IFRS/IAS?

To answer the research question a literature review and an empirical study were done, using a sample of non-financial Portuguese companies listed on Euronext Lisbon. After the data collection for the period 2005–2015 (533 firm-years observations) and the analysis of audit reports, we tested the Jones modified model (Dechow et al., 2003). The research results, provided by Model 1, show that non-financial companies after the mandatory adoption of IAS/IFRS (2005) present evidence of earning management practices, similar to what happens in other countries (Barth et al., 2008; Goncharov & Zimmermann, 2006; Tendeloo & Vanstraelen, 2005).

This investigation provides a contribution to the literature, since it shows that in a country of continental Europe, more than a decade after the mandatory adoption of IAS/IFRS, earning management continue to exist as has happened before in Anglo-Saxon and other countries (Baralexis, 2004; Othman & Zeghal, 2006). Consequently, we contribute to the debate about the relative benefits and costs of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) adoption.

While it is important to study the behavior of earnings management, this research is not without limitations. Among others, it recognizes the need to come to use other proxies to classify companies as manipulators of the results; the need to use a larger sample size and the importance of considering other models and analysis methodologies.

Following this investigation, it seems important to develop a research to examine the issue of earnings management in unlisted companies and make a comparative analysis of listed and unlisted companies. In 2010, unlisted companies have adopted an Accounting Standards System that is based on International Accounting Standards (IAS/IFRS), it seems important to analyze the earning management behavior of companies in the face of a major regulatory change.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Fernandes’ study (2007) analyzed the impact of IFRS on earnings management for the Iberian Peninsula for the periods 2002–2004 (pre-IFRS) and 2005–2006 (post-IFRS).

The modified-Jones model (Dechow, Richardson, & Tuna, 2003) predicts deflation by total assets at the end of period t−1, but due to the consolidation of accounts, particularly changes in the perimeter of the consolidation, we chose as Borralho (2007) by the end of the period t.