Material flow cost accounting (MFCA) is a tool designed to encourage eco-efficiency in organizations by focusing on a reduction in use of materials and related improvements in economic performance of corporations. It provides a way to identify win–win situations where monetary and environmental performance can both be improved. But take-up by business is slow, which seems to go against the notion of strong competition driving economic performance. A recent standard, ISO 14051, has been produced by the International Organization for Standardization, and could bring substantial change to MFCA implementation and research. Drawing on Rogers (2003) theory of diffusion of innovation, and with a focus on the first two stages of the innovation-decision process, knowledge and persuasion, this study sought to analyze MFCA and predict how the 2011 release of ISO 14051 might be expected to influence take-up of MFCA by business, and what this might mean for future research. The analysis revealed that, when combined with ISO involvement, MFCA is well placed in terms of Rogers’ theory, with the future likely to see increased diffusion of MFCA and, as adoption rates increase, more opportunities for research in this area. Specific areas identified as a result of the analysis include: the introduction of new research methods, the need for theoretically informed research, and the potential to address new research questions previously considered impractical.

La contabilidad de costes del flujo de materiales (MFCA) es una herramienta diseñada para fomentar la eficiencia ecológica en organismos al centrarse en una reducción del uso de materiales y en las mejoras relacionadas con el rendimiento económico de las empresas. Permite identificar las situaciones beneficiosas para ambas partes en las que puedan mejorar tanto el rendimiento monetario como el ambiental. La Organización Internacional de Normalización ha creado recientemente el estándar ISO 14051, que podría suponer un cambio sustancial en la puesta en marcha de la MFCA y la investigación. Basándose en la teoría de difusión de la innovación de Rogers (2003) y centrando la atención en las primeras 2 fases del proceso de innovación-decisión, conocimiento y persuasión, el presente estudio pretende analizar la MFCA y predecir cómo se espera que el lanzamiento del ISO 14051 influya en la implantación de la MFCA por las empresas, y lo que esto significaría para las futuras actividades de investigación. El análisis reveló que, en combinación con el ISO, la MFCA está bien posicionada respecto a la teoría de Rogers, con una tendencia en el futuro de ver una mayor difusión de la MFCA y que, a medida que las tasas de puesta en marcha sean mayores, surgirán más oportunidades de investigación en este campo. Entre las áreas específicas identificadas como resultado del análisis se incluyen: la introducción de nuevos métodos de investigación, la necesidad de una investigación teóricamente informada y el potencial de enfrentarse a nuevas cuestiones de investigación anteriormente consideradas inviables.

Material flow cost accounting (MFCA) is an environmental management accounting (EMA) tool with the introduction of a new international standard, ISO 14051, likely to increase its take-up in the near future (ISO, 2011). EMA is the term used to describe the integration of physical and related monetary environmental information into the management accounting system (Jasch, 2006). EMA incorporates a variety of tools that can be physical or monetary; past or future-oriented; routinely generated or produced on an ad-hoc basis; and finally, they can have either a short or long-term focus (Burritt, Hahn, & Schaltegger, 2002). ISO 14051 defines MFCA as a “tool for quantifying the flows and stocks of materials in processes or production lines in both physical and monetary units” where ‘materials’ include energy and water (ISO, 2011, p. 3). These flows and stocks of materials are important because they pervade business practice (Jasch, 2006). The aim of MFCA is to provide information to management about opportunities for reducing materials use and improving monetary performance of businesses at the same time, an irresistible opportunity.

To date the potential implications associated with the release of ISO 14051 have gone almost unremarked within the literature. Given the contemporary nature of the topic it can be argued this is not unexpected. Nonetheless there is reason to believe this event could bring about substantial change for both MFCA application and research. Drawing on an analysis of extant literature and informed, in part, by Rogers’ (2003) theory on diffusion of innovation, it is the purpose of this paper to examine this potential and to identify related areas of importance for future MFCA practice and research. With especial focus on the innovation-decision process and, in particular, the importance of knowledge and persuasion to the diffusion of MFCA in the business population, the paper provides an in-depth analysis of MFCA and ISO 14051. In addition, by applying Rogers’ (2003) theory prospectively the paper demonstrates the potential for diffusion of innovation to be applied for analysing and predicting diffusion rates associated with new innovations, as well as those where the diffusion process appears to have stalled (Dunne, Helliar, Lymer, & Mousa, 2013).

The analysis and conclusions are expected to be of interest to practitioners, environmental accounting and management researchers, and those academics concerned about the interplay between movements towards sustainability and business.

The remainder of this paper is arranged as follows. The section “MFCA – a brief overview” provides a brief introduction to MFCA as a research topic. This is followed by “ISO 14051: implications for MFCA” which reflects upon the release of ISO 14051 and the ways in which this might influence MFCA take-up in practice. “A new era for MFCA research – directions and opportunities” considers areas for future research after which conclusions of the paper are drawn.

MFCA – a brief overviewMaterial flow cost accounting (MFCA) has been described as one of the most basic and well-developed EMA tools (Schaltegger & Zvezdov, 2015; Sulong, Sulaiman, & Norhayati, 2015). Given cost accounting is itself one of the most fundamental facets within contemporary management accounting it can be argued this observation is unsurprising. Notwithstanding this position a recent review undertaken by Christ and Burritt (2015) revealed poor take-up of MFCA by business, even though case-based research has consistently shown MFCA implementation to be associated with positive outcomes in a growing number of case organisations (for example, see Jasch & Danse, 2005; Scavone, 2006; Schaltegger, Viere, & Zvezdov, 2012).

As with EMA in general, MFCA is currently an unregulated activity. Hence it is up to individual organisations to determine the practices that are most appropriate to their operations. Case-based research has routinely revealed MFCA to provide a means to identify areas of inefficiency relating to material quantities and costs and, by doing so, make visible potential for cost reductions and eco-efficient outcomes. Thus, it is somewhat surprising evidence indicates few organisations are availing themselves of the practice. There are several potential reasons for this observation.

First, to date, MFCA literature has been largely driven by action-based case studies in which experienced academics have played a leading role in facilitating the implementation process (Heupel & Wendisch, 2003; Jasch, 2006; Schaltegger et al., 2012). Whether the case organisations would have engaged with MFCA in the absence of such involvement is unclear. Furthermore, the level of MFCA knowledge within organisations prior to involvement with this type of research remains unknown in most cases. In the absence of academic guidance and drive extant knowledge within the management group is likely to be very important when assessing the potential benefits of MFCA, given this can be expected to influence the implementation decision. Research has demonstrated MFCA to have substantial potential to lead to tangible economic and environmental improvements in a large range of organisations; however, if managers are not familiar with this research the sum of these benefits is likely to remain unnoticed.

Prior research has shown that even in Germany and Japan, two of the prime instigators responsible for early development of the MFCA tool, many companies remain ill-informed with regard to the MFCA process and few elect to implement the practice fully within their operations (Burritt & Tingey-Holyoak, 2012; Kokubu & Nashioka, 2005; Schaltegger, Windolph, & Herzig, 2011; Schmidt & Nakajima, 2013). Drawing on a study of sustainability management tools used in large German companies, Schaltegger et al. (2011) present evidence that the more well-known an environmental accounting tool is, the more likely it will be adopted in practice. Hence communication channels and publicity are important, and this is an area with regard to which the release of the ISO 14051: Material Flow Cost Accounting standard can be expected to be of great assistance. In light of this development it is the purpose of this paper to consider the following research question: (RQ) Given the recent release of ISO 14051, what is the likely future for MFCA research and implementation in practice?

The following section will commence this analysis by considering the release of ISO 14051 and why this event might be expected to impact MFCA practice and research.

ISO 14051: implications for MFCAA recent development that is likely to alter current perceptions and take-up of MFCA by business is the 2011 release of ISO 14051: Material Flow Cost Accounting by the International Organization for Standardization. The aim of this standard is to: […] offer a general framework for material flow cost accounting (MFCA). MFCA [being] a management tool that can assist organizations to better understand the potential environmental and financial consequences of their material and energy use practices, and seek opportunities to achieve both environmental and financial improvements via changes in those practices (ISO, 2011, p. v)

Despite limited evidence supporting its usefulness beyond manufacturing settings (Christ & Burritt, 2015; Papaspyropoulos, Blioumis, Christodoulou, Birtsas, & Skordas, 2012), the standard advocates MFCA as a tool that is applicable “to any organization that uses materials and energy, regardless of their products, services, size, structure, location, and existing management and accounting systems” (ISO, 2011, p. 1) (also see Jasch, 2009).

It is not the purpose of this section to describe the MFCA process in detail, nor to provide a timeline of MFCA development from inception to the present. There are other publications available for readers who are interested in a more comprehensive understanding of these topics (for example, ISO, 2011; Jasch, 2009; METI, 2007). Rather, it is the purpose of this section to reflect on how the release of ISO 14051 might be expected to increase knowledge and take-up of MFCA in practice. This information will then be used to assess research implications and identify feasible areas for future investigation.

In a recent review, Christ and Burritt (2015) observed theoretically driven MFCA research to be non-existent. Nonetheless theory has much to offer. For example, Rogers’ (2003) theory on Diffusion of Innovation offers a potential lens through which to understand how ISO 14051 might be expected to increase MFCA engagement by business. The following section will consider this potential in more detail.

Diffusion of innovation – drivers of take-upRogers’ (2003) seminal work and resultant theory on diffusion of innovation sought to provide an explanation for how technological and administrative innovations come to permeate specific populations. Sulong et al. (2015, p. 3) recently extended this notion to include MFCA with the authors describing the practice as “an innovative managerial technology”.

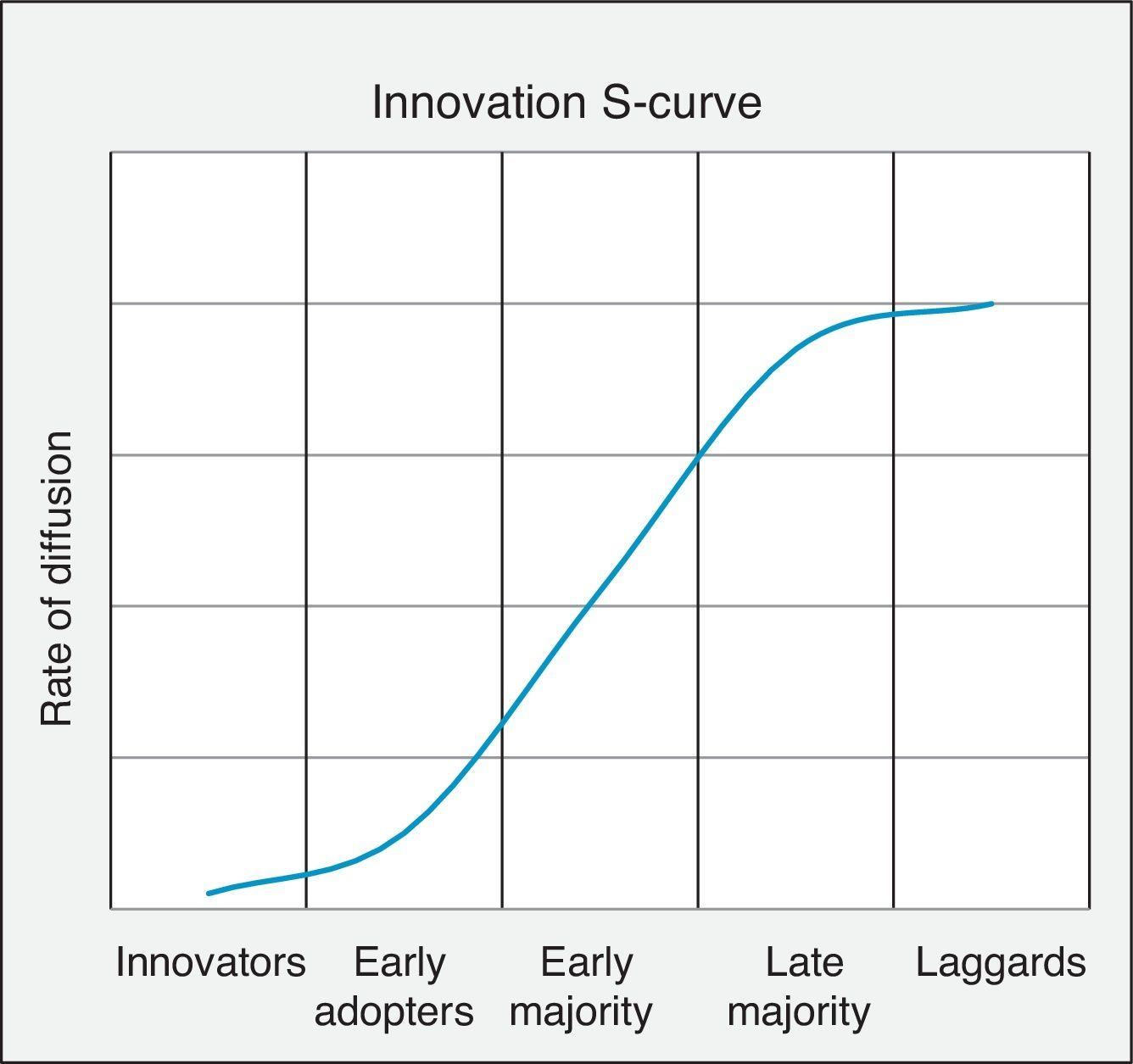

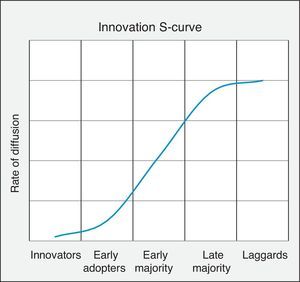

There are two elements within diffusion of innovation that are likely to be useful and applicable in the present context. First, Rogers (2003) argues that the cumulative rate at which an innovation is adopted within a population tends to follow a horizontal S-curve from innovators to laggards. Initial adoption tends to be slow led by innovators and early adopters after which implementation speeds up before dropping off again as the laggards finally get involved and a saturation point is attained. This notion is visually depicted in Fig. 1. Upon considering evidence of poor take-up of MFCA by business (for example, see Burritt & Tingey-Holyoak, 2012; Kokubu & Nashioka, 2005; Schaltegger et al., 2011), it can be argued that as an innovation MFCA lies towards the beginning of the S-curve; possibly around the ‘early adopters’ stage (Sisaye & Birnberg, 2012).

The innovation S-curve (adapted from Rogers, 2003).

Nonetheless it can be argued the current rate of adoption will not remain in perpetuity, with the release of ISO 14051 likely to move implementation of MFCA within the business population further along the innovation curve. However, in order to appreciate how this might occur, it is necessary to understand the innovation-decision process and to analyse ISO 14051 through this lens. This is another area with regard to which Rogers’ (2003) theory can greatly assist.

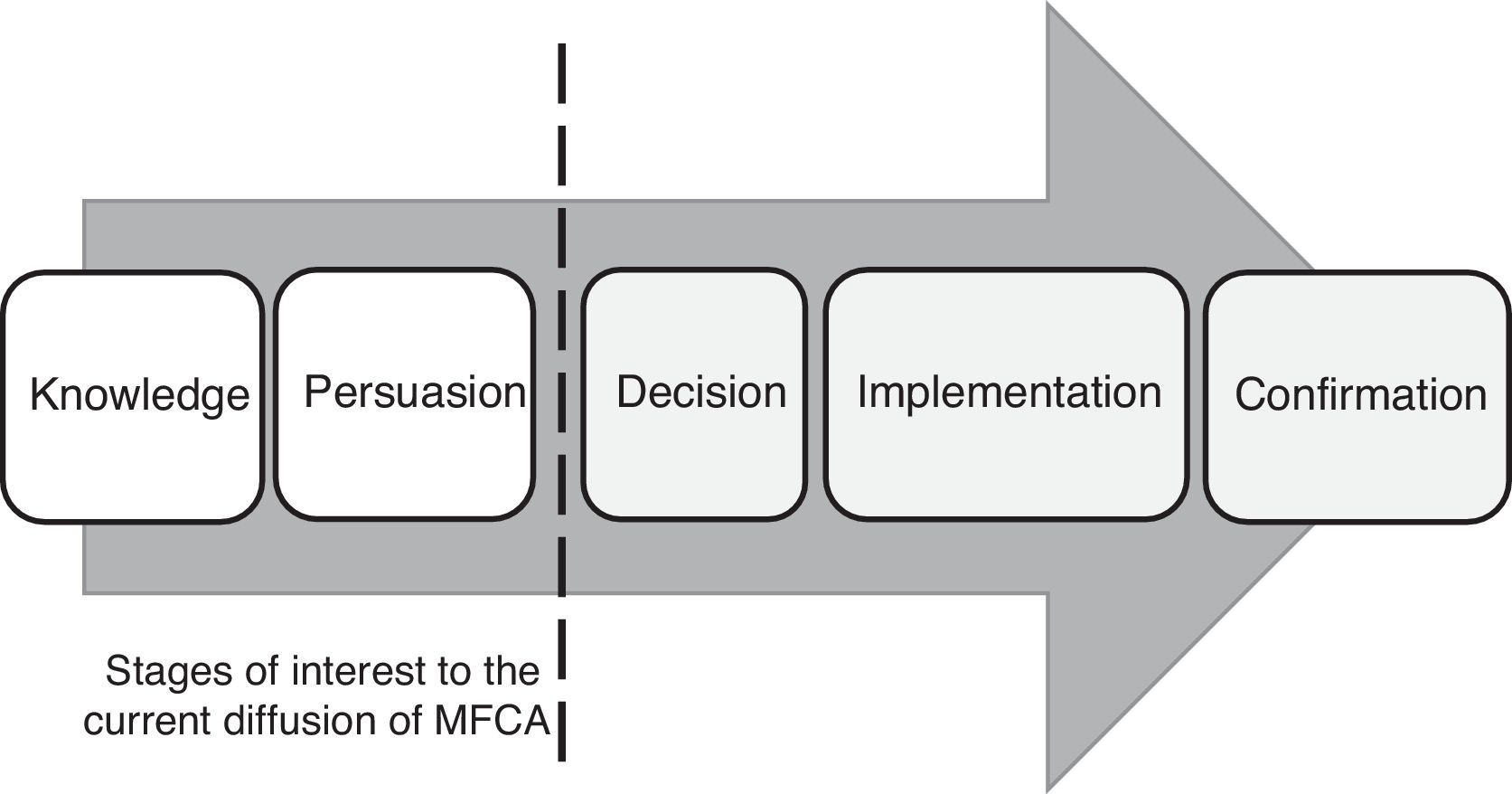

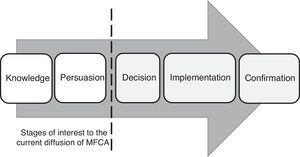

Rogers (2003) posits that when making the decision to adopt an innovation, organisations will observe a process that incorporates each of the following stages: knowledge; persuasion; decision; implementation; and confirmation (see Fig. 2) (for further information, please refer to Rogers, 2003). In the case of a new innovation or, as observed by Dunne et al. (2013), when the diffusion process associated with a more established innovation appears to have stalled, the knowledge and persuasion stages become very important. Given evidence suggesting low take-up of MFCA in practice, the early stages of the innovation-decision process become very important and it is here that the release of ISO 14051 can be expected to have a great influence. This potential will be discussed below.

The innovation-decision process (adapted from Rogers, 2003).

To date the promotion of MFCA has been largely driven by academics, the accountancy bodies (e.g. IFAC, 2005), select government initiatives (e.g. METI, 2007) and non-government organisations, including the United Nations (United Nations Division for Sustainable Development, 2001). Hence mainstream exposure to MFCA by the wider business community has been limited and, even when information is readily available, there is likely to be a lag between initial exposure and eventual take-up. Such a lag might explain the results obtained by Kokubu and Nashioka (2005) who, in 2005, found that only 6.5% of Japanese companies had partially implemented MFCA in their operations despite 73.5% of companies reporting knowledge of the practice. Given Japanese authorities only commenced promotion of MFCA in 2000 these results provide anecdotal evidence of a diffusion lag and should not be interpreted as providing evidence that the practice is not useful (Kokubu & Tachikawa, 2013).

It can be argued the release of ISO 14051 will expose the larger business community to MFCA on a level that has not been seen before within the EMA area. Such institutionalisation might lead to ISO involvement being different from previous initiatives. To begin, ISO is an international body with an international reputation for offering solutions to contemporary, and in some cases universal, business problems (Reynolds & Yuthas, 2008; Rezaee & Szendi, 2000). Many organisations will already have knowledge of, or experience with, ISO standards and while negative experience with other standards in the past might influence how some organisations view ISO 14051 (Hillary, 2004), in general it can be argued ISO involvement brings a new level of credibility to MFCA that has hitherto been absent. Furthermore, in order to survive, ISO relies on profitability from memberships, available experts that participate in projects, and selling standards. Hence it sets out to understand potential markets and pick winners. Diffusion of knowledge about the standards is key to success.

With a current membership in excess of 160 countries, ISO standards have an exceptionally wide reach (ISO, 2014). ISO standards are also popular with consultants resulting in a large number of outlets from which business organisations can obtain additional information and advice (Heras-Saizarbitoria & Boiral, 2013). In addition, the nature of standardisation means everyone working with ISO 14051 will be commencing from an identical foundation of definitions and assumptions (Schaltegger & Zvezdov, 2015). This should facilitate transferability of knowledge between countries and companies while also allowing reluctant managers to observe the experience of organisational peers before committing to full implementation within their own organisations (Sisaye & Birnberg, 2012).

Given prior research has shown external stakeholders to play an important role in “fostering innovation and diffusing knowledge” of new technologies, the role of consultancy firms as change agents in moving MFCA diffusion further along the innovation S-curve should not be underestimated and this is an area that would benefit from additional research (Cooper & Crowther, 2008; Dunne et al., 2013, p. 170; Rogers, 2003).

Thus far this section has described how the release of ISO 14051 might be expected to increase exposure and enhance the credibility associated with MFCA thereby increasing knowledge of the tool in practice. As previously discussed and also displayed in Fig. 2, this is the first step in the innovation-decision process (Rogers, 2003). However, while knowledge could reasonably be expected to increase the overall take-up of MFCA by business, as described by Schaltegger et al. (2011), it is not an end in itself. Indeed, ‘persuasion’ which represents the next step in the innovation-decision process is equally important to the ultimate diffusion of MFCA (refer to Figs. 1 and 2). The next sub-section will consider the facet of persuasion in more detail.

The characteristics of MFCA as an innovationRogers (2003) identified five characteristics inherent in all innovations that are likely to facilitate, or hinder, their diffusion to members within a population. Indeed, these attributes have been remarked as among the most crucial aspects in the innovation–adoption decision (Yazdifar & Askarany, 2012). According to Rogers (2003) these characteristics include: relative advantage over existing practice; compatibility with existing values, experience and needs of the potential adopter; overall complexity; observability, or the degree to which the results can be observed and communicated; and, finally, trialability, meaning the extent to which potential adopters can experiment with the innovation on a limited basis (Rogers, 2003).

Although MFCA has gone largely overlooked in the literature on diffusion of innovation, a recent study by Sulong et al. (2015) explicitly considered this interplay. Nonetheless, drawing on established literature from related areas it is possible to speculate as to how MFCA might be perceived by the business sector and how the release of ISO 14051 might contribute to, and potentially alter, these perceptions.

The first and arguably most pervasive attribute associated with the adoption of either technological or administrative innovations is relative advantage (Smerecnik & Anderson, 2011; Smith, Abdullah, & Abdul Razak, 2008). Relative advantage includes implementation costs, potential profitability or cost savings, the speed at which benefits are expected to be realised, time and effort required for implementation, ease of use, etc. (Rogers, 2003; Yazdifar & Askarany, 2012). In a recent study of MFCA implementation in an SME located in Malaysia, Sulong et al. (2015) suggest that if managers are able to see the potential for simultaneous economic and environmental improvement via MFCA, where other accounting and environmental management systems only allow for one or the other, it is likely the diffusion of MFCA will be faster. Similarly, Pérez-Méndez and Machado-Cabezas (2015) observe that if organisations are dissatisfied with their current accounting systems they will be more likely to consider and implement new management tools, like MFCA. Case-based research on MFCA provides evidence in support of this potential (Kurdve, Shahbazi, Wendin, Bengtsson, & Wiktorsson, 2015). For example, in Sulong et al. (2015) the case organisation was able to visualise areas of material inefficiency quickly and accurately calculate material losses that would otherwise have been hidden in general overhead accounts. This study also provides evidence of cost-effective implementation, which is likely to be an important consideration for many organisations.

In a similar vein, Schaltegger et al. (2012) used MFCA expeditiously to demonstrate areas of inefficiency at a beer brewing facility in Vietnam. Not only did this study identify energy and water use double that of an equivalent facility in Germany, MFCA allowed the management team a better understanding of where energy and water were used within their facilities. These two studies suggest there are many advantages associated with MFCA that are likely to appeal to business organisations looking for efficiency gains and the potential for cost reductions.

Furthermore, it can be argued ISO 14051 has a number of advantages over other environmental standards such as ISO 14001, which will also appeal to corporate managers. For example, ISO 14051 is a guidance standard as opposed to a certification standard. What this means is that the standard relies on “self-motivated implementation” (Castka & Balzarova, 2008, p. 231). The lack of certification allows for cost effective implementation which may assist with oft cited arguments that the benefits associated with implementation of certified accounting and/or environmental standards do not justify the immediate and long-term costs that often accompany adoption (e.g. annual or bi-annual audit costs) (Chavan, 2005).

The preceding section provides evidence to suggest that MFCA and the related ISO 14051 standard have much to recommend them to contemporary managers in terms of relative advantage. However, this is only the first characteristic observed by Rogers (2003). Compatibility, the second, will be discussed next.

Compatibility concerns the degree to which MFCA and ISO 14051 as innovations are likely to be consistent with the values and goals of the organisation (Yazdifar & Askarany, 2012). MFCA, because of its ability to generate both monetary and environmental performance gains, is likely to be consistent with the values of organisations that are concerned with efficiency and minimising areas of environmental concern, while also being compatible with economic objectives which remain a pervasive element of contemporary business practice (Christ & Burritt, 2015; Godschalk, 2008). Given MFCA has been described as an extension of the cost accounting system, within their current records many organisations will already have much of the information required to undertake MFCA (Scavone, 2006; Schaltegger et al., 2012). While this may not always apply to the small or micro-sized, it is anticipated many organisations will be well placed to engage with MFCA activities (Jasch, 2009).

The compatibility of ISO 14051 with other management systems and standards also requires discussion. It has already been observed that many organisations are familiar with various ISO standards (Reynolds & Yuthas, 2008; Rezaee & Szendi, 2000). In many cases these standards are designed to be complimentary. For example, ISO 14051 like most of the standards in the 14000 and 9000 series encourages a focus on a plan-do-check-act cycle (PDCA) designed to foster continuous improvement (ISO, 2011). Hence it is likely ISO 14051 will be especially well placed in organisations and with management teams that have had previous experience with one or more ISO standards.

The third characteristic that Rogers (2003) observed to be associated with the rate at which innovations diffuse to a population is complexity. Adopters tend to favour simplicity when deciding which innovations to implement within their organisations. If an innovation is difficult to use and/or understand, it is less likely potential adopters will make the decision to implement it. In the study of Sulong et al. (2015) it was observed that “employees from various units in the [case organisation] were able to understand the concepts in MFCA comparatively easily”. Kasemset, Sasiopars, and Suwiphat (2013) concur with this observation noting the presentation of MFCA is often easy to understand even by non-specialists in the management team. Indeed, the nature of MFCA teams is transdisciplinary requiring, for example, the expertise of engineers and accountants to be integrated for successful implementation within organisations (Tingey-Holyoak & Burritt, 2012; Tingey-Holyoak, Pisaniello, & Burritt, 2014).

Further to the above, it can be argued the release of ISO 14051 will reduce the level of complexity for potential adopters even further. For example, this standard includes a clear overview of terms and definitions, purpose and scope, as well as easy to understand examples which clearly demonstrate the interplay between material flow and cost. Five case examples are also included. At only 46 pages in length the document is both concise and precise which is likely to appeal to time-stressed managers who may be more able to appreciate the benefits of MFCA as an organizational innovation (ISO, 2011).

The penultimate attribute noted by Rogers (2003) as having potential to hasten the diffusion process is observability. Sulong et al. (2015) describe this trait as being “whether MFCA results are easily observed and communicated to others”. Previous research has shown MFCA to be a process that can produce results over a short period of time (Jasch & Danse, 2005; Scavone, 2006; Staniskis & Stasiskiene, 2005). Furthermore, the process of expressing material flow information in monetary terms is likely to be a selling point with business managers given it is still the financial bottom-line which dictates business decisions in a large number of corporate organisations (Godschalk, 2008; Staniskis & Stasiskiene, 2006). The observability of MFCA was noted in Sulong et al. (2015) with case organisation, Alpha, able to articulate easily and explain their MFCA experience to the other organisations involved with the Malaysia Productivity Corporation's MFCA project. Similarly in a study presented by Nakano and Hirao (2011) it was easier to convince the business networks of three Japanese companies on the merits of MFCA in comparison with life-cycle analysis; the latter being more complicated and lacking the monetary element.

Although it is unclear how the release of ISO 14051 may contribute to, or enhance, the observability of MFCA as an innovation, the standard does include numerous examples, especially within Annex A through C, of how the physical and monetary information generated from MFCA might be presented (e.g. tables, flow charts) (ISO, 2011). It is possible these examples will provide useful guidance to organisations as to the best way to present MFCA information. For example, previous research has shown flow models to be a useful way of communicating material flow information (Heupel & Wendisch, 2003; Kokubu & Tachikawa, 2013). However, at this time the proposed role for ISO 14051 outlined above is conjectural and further research investigating how ISO 14051 might contribute to the observability of MFCA information would be beneficial.

The final attribute associated with the diffusion of innovation in a population is trialability (Rogers, 2003). This attribute refers to the extent to which an organisation can experiment with MFCA prior to full implementation. The trialability of MFCA is well documented in extant literature. Indeed, evidence suggests early experiments with MFCA within organisations are usually confined to pilot projects that involve either a single process or product line (IFAC, 2005; Scavone, 2005; Staniskis & Stasiskiene, 2006). Hence organisations are able to implement MFCA on a limited basis which should allow them to assess whether the practice is likely to be feasible and useful given their current activities and position. This feature was found to be important in the case study presented by Sulong et al. (2015) with the case organisation able to conduct three trial runs with MFCA to assess its suitability to their operations. From here organisations can then decide to extend their MFCA activities to include other processes, the entire organisation or, in its most developed form, their entire supply chain (METI, 2007; Nakano & Hirao, 2011).

The trialability aspect of MFCA is well articulated with the ISO 14051 standard. Indeed the standard goes so far as to recommend trial projects focussing on areas of greatest potential benefit. For example: The boundary can encompass a single process, multiple processes, an entire facility, or a supply chain at the discretion of the organization. However, it is advisable to focus initially on a process or processes with potentially significant environmental and economic impacts – emphasis added (ISO, 2011, p. 10)

Hence it is probable that increased exposure to ISO 14051 will highlight the trialability inherent in MFCA to potential adopters. Based on Rogers’ (2003) work and other studies which have drawn on diffusion of innovation as a framework, it can be argued this will facilitate the speed at which MFCA is likely to diffuse to the business population (Damanpour & Schneider, 2009).

Other factors associated with diffusionBefore discussing the potential for new research in the MFCA area, it is necessary briefly to discuss several other factors shown by previous research to be associated with the diffusion of innovations to a population. In her 2002 paper, Wejnert suggests that in addition to the characteristics of the innovation itself, the rate at which an innovation is adopted can also be affected by the characteristics of innovators and environmental context the latter of which is of especial interest to MFCA.

Wejnert (2002, p. 299) posits that the ultimate rate of diffusion is likely to be associated with organisational factors such as geographical settings, societal culture, political conditions and global uniformity. Even though the International Organization for Standardization has an international standing, as discussed in the section on “ISO 14051 – increased exposure and credibility”, it is possible the rate of MFCA diffusion might be affected by such environmental aspects. For example, in some countries, such as Japan, cultures appear more resistant to change whereas others like the US tend to foster the spread of innovations (Hofstede, 2001). In contrast, other researchers suggest countries like Japan, which is characterised by a high level of uncertainty avoidance, will tend towards higher levels of environmental activism (Ho & Taylor, 2007). Given scant attention has been extended to understanding cross-cultural differences in MFCA adoption within past literature, it would be interesting, as noted by Meade and Islam (2006), to observe and model how national culture affects the diffusion process of administrative innovations like MFCA. Indeed, with ISO 14051 providing a platform of identical definitions for organisations regardless of the societal culture in which they operate, there is an opportunity to investigate the way in which culture influences the eventual level of take-up of MFCA, as well as the way in which it is promoted and implemented. This could be observed cross-sectionally and over time. Prior research suggests such enquiry could prove insightful (Griffith & Yalcinkaya, 2008; Maitland, 1999). It would be especially interesting, for example, to consider how the release of ISO 14051 influences diffusion of MFCA in Germany and Japan as two of the main instigators behind historical MFCA development. In summary, although it is probable that different aspects of environmental context will ultimately influence ISO 14051 diffusion and MFCA take-up, future research will be required to ascertain exactly how this will occur in practice.

Drawing on diffusion of innovation, this section offered evidence suggesting that the release of ISO 14051 is likely to afford MFCA a more prominent place on the corporate agenda. Based on the innovation-decision process presented in Fig. 2, ISO 14051 will afford MFCA more exposure and credibility, increasing knowledge of the practice in the target population, as discussed in the section on “ISO 14051 – increased exposure and credibility”. It is also well placed in terms of the innovation attributes described by Rogers (2003) which, based on previous research on diffusion, should position MFCA well in terms of ‘persuasion’ – an important step in determining the ultimate decision to adopt, or not adopt, the management tool. Taken collectively these developments suggest the future will see increased corporate engagement with MFCA. What this might mean for research activities is examined in the next section.

A new era for MFCA research – directions and opportunitiesAs the diffusion of MFCA in the business population increases and the rate of adoption shifts along the S-curve from innovators and early adopters to the early majority (see Fig. 1), new opportunities for research in the MFCA field can be expected. Directions for future research can be divided into several categories which include the feasibility of new research methods, possibilities for theoretically driven projects and the potential to address new research questions previously considered impractical. Each of these directions will be considered below.

As previously mentioned and also observed in a recent review by Christ and Burritt (2015), to the present time MFCA research has been primarily driven by action-based case studies. Although this research was important to the early development of the MFCA tool (Escobar-Rodríguez & Gago-Rodríguez, 2012), as more organisations begin to engage with the practice it should be possible to move beyond this one-dimensional focus. For example, in the immediate term it would be useful to conduct case studies and comparative case studies of organisations that have voluntarily implemented MFCA based on exposure to the ISO 14051 standard. Understanding the difficulties that emerge when experienced researchers are not present onsite might provide useful insight that can be used for future MFCA promotion.

As evidence emerges of increased MFCA take-up, other research methods will also become viable. These include interview based initiatives and large scale quantitative projects (e.g. surveys) in which statistical analysis is employed. For example, it would be of use to conduct interview and survey-based research with consultants who are involved with the promotion and implementation of the ISO standards. Given this group has been identified as potentially important change agents in the diffusion of administrative and technological innovations (Heras-Saizarbitoria & Boiral, 2013), they may be able to provide unique insight into how MFCA is perceived by business managers and also the barriers and enablers that may exist to hinder or support its implementation across a wider population and in multiple settings. Likewise interviews with, or surveys of, accounting education providers as potential change agents towards sustainability would assist gaining an understanding of how MFCA would fit in mainstream accounting curricula or as a modular addition (Peer & Stoeglehner, 2013).

Further to the above it would also be helpful to follow MFCA development longitudinally to see how it develops over time. Given current levels of MFCA take-up place it towards the beginning of the innovation S-curve and with ISO 14051 likely to advance future MFCA adoption as previously discussed, researchers are in the unique position of being able to observe the process of MFCA diffusion over time. The potential for new knowledge and insight becomes even more apparent when one considers that, to date, the literature on diffusion of innovation has been primarily concerned with the study of innovations that are already fully diffused (Yazdifar & Askarany, 2012). While not wishing to disparage this type of research, there is much that can be learned over a period of time from following the diffusion process (Bohlmann, Calantone, & Zhao, 2010).

Thus far this section has considered the potential for new research methods in the study of MFCA in practice. However, theoretical explanations for MFCA also require further study. In their recent review of the MFCA literature, Christ and Burritt (2015) found theoretically driven research within this literature to be non-existent. A recent exception is the study of Sulong et al. (2015) who use diffusion of innovation to examine MFCA in a case study of a Malaysian company. The discussion presented here also drew on diffusion of innovation to describe how the release of ISO 14051 might be expected to increase future engagement with MFCA by business. While future research which examines the interplay between diffusion of innovation and MFCA take-up would certainly be beneficial, there are many other theories that could prove equally insightful. The need for strong theoretical foundations as a base from which to develop future business research has also been observed by Argilés and Garcia-Blandon (2011) who additionally draw attention to the importance of replication in the furthering of knowledge.

Lewin (2014), in a recent editorial for Management and Organization Review, observed significant crossover between theories in management research, many of which examine “the same and/or overlapping phenomena”, which might explain the low variance obtained in a large number of management studies (Lewin, 2014, p. 168). What this means for future MFCA research is that researchers should not confine themselves to any one theoretical approach and look instead for contrast and complementarity between them. For example, the limited take-up of MFCA observed in past research raises the question as to when MFCA works. Context and performance are likely to be important elements in this process an understanding of which will be required to formulate an answer to this question. Hence it can be argued contingency theory, which identifies different contextual settings for decision making, would be useful for this purpose (Chenhall, 2003).

Other theories seek to explain drivers of and catalysts for organisational practice. Examples include, but are not limited to, institutional theory, stakeholder theory, and legitimacy theory. In order to examine how these theories might relate to MFCA implementation, it is necessary first to have a sufficient population of adoptees from which to draw a sample. Such adoption should be self-motivated and not driven by active involvement by academics if conclusions based on large databases of information and associated inter-subjectively testable statistical analysis are to be valid. Hence, use of these theories will only be feasible at a time when diffusion of MFCA is more advanced and explanatory rather than exploratory case research possible. Furthermore, theory development relies, in part, on the use of multiple and complimentary research methods (Kong & Thomson, 2009; Wynekoop & Russo, 1997). As adoption levels increase it will be possible to examine MFCA using the full range of qualitative and quantitative research methods available to the contemporary researcher as discussed earlier in this section (Gable, 1994). This will lead to a more comprehensive understanding of MFCA and wider theoretical and empirical generalisations which can be used to guide practice. In summary, there are many opportunities for theory driven MFCA research that are likely to emerge in the immediate future; however, most of these opportunities will only become viable once time has passed and implementation rates improved.

The release of ISO 14051 will also change the type of research questions that can be asked in future projects. For example, it will be useful to examine how the release of this standard changes perceptions and take-up of MFCA by the business sector. This paper used diffusion of innovation and prior research in related areas to speculate as to how this event might impact the overall level of MFCA engagement. Thus, it would be useful to examine the sectors in which this is likely to occur. Although MFCA has been suggested as being useful to organisations regardless of the sector or industry in which they operate (Christ & Burritt, 2015; ISO, 2011), this is an area that needs to be empirically examined. Furthermore, with over 160 member countries involved with the International Organization for Standardization, it can be expected that organisations across multiple cultures might start experimenting with MFCA activities. As alluded to in the section on ‘other factors associated with diffusion’, this should provide a unique opportunity to study how national culture affects both the implementation and effectiveness of MFCA in different settings.

With regard to release of the ISO standard it should also be possible to conduct a more thorough investigation of barriers and facilitating factors that drive MFCA in practice. The role of consultants, as previously discussed, could be a useful avenue to examine in this regard. How ISO 14051 changes perceptions of MFCA among business managers, and as an extension EMA in general, would also benefit from study. For example, to what extent does the standardisation process work to legitimise MFCA in the eyes of the business community? Also, to what extent do the proposed economic and environmental benefits outlined in ISO 14051 correspond with the actual experience within organisations that choose to apply the standard? It may be there are certain conditions under which tangible benefits will be more likely to be realised and this would benefit from further research. For example, in larger organisations it is likely there will many functions involved with the MFCA process (Burritt et al., 2002) and a greater understanding of the interplay between these functions (e.g. who is involved with preparing MFCA data, how is MFCA data communicated to different departments, etc.) would be beneficial. Indeed, ISO 14051 specifically promotes the need for teamwork across functions with the information provided by MFCA designed to support decisions within multiple areas of the business (ISO, 2011).

Finally, although it has been suggested that the release of ISO 14051 can be expected to increase MFCA take-up by the business population, this does not necessarily mean every organisation will maintain its involvement with the practice. Indeed, it is conceivable that a number of organisations will decide to abandon the practice in favour of other management and accounting systems. In these cases it would interesting to understand why this decision is made. For example, did the expected benefits of MFCA as articulated in ISO 14051 result in unreasonable expectations on the part of managers? The section on ‘ISO 14051: implications for MFCA’ notes that one of the benefits associated with MFCA is its trialability. However, ISO 14051 also argues that in establishing pilot projects and trials “it is advisable to focus initially on a process or processes with potentially significant environmental and economic impacts” (ISO, 2011, p. 10). Hence an important question might be how organisations select the process or product to include in such trials. ISO 14051 assumes that organisations will be able to adequately assess which processes are likely to bring about the greatest potential for benefit. However, as seen and discussed earlier, the study of Schaltegger et al. (2012) found this assumption is not always reasonable. Poor selection at the trialability stage could reasonably lead to early abandonment of MFCA even if the practice does in fact have potential to be useful in other areas of the organisation. Given pilot projects and trials are likely to be important to the ultimate diffusion of MFCA, understanding how trials are selected and how they impact further implementation decisions will also be an important area for future study.

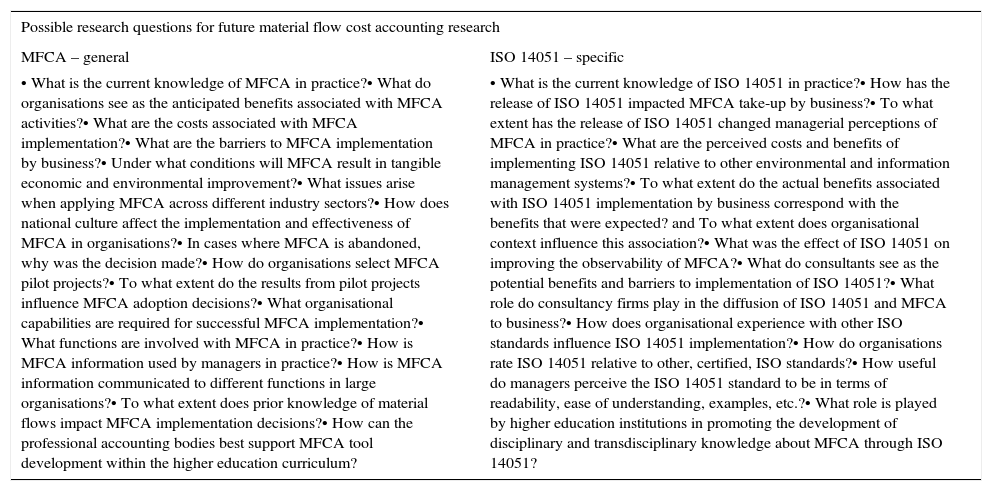

It should be noted that the proposed methods, theories and research questions presented above do not represent an exhaustive list and they should not be treated as such. Rather it was the purpose of this section to demonstrate the many areas and opportunities for future research into MFCA in practice and how the recent release of ISO 14051 can be expected to increase these opportunities. A list of potential research questions, further to those presented above is provided in Table 1. Given MFCA has been noted as being among the most fundamental EMA tools, and that previous research has consistently shown take-up of generic EMA activities by business to be limited, there is also an opportunity to learn from the MFCA experience with a view to developing improved EMA tools and more effective promotional activities in the future.

Possible questions for future MFCA research.

| Possible research questions for future material flow cost accounting research | |

|---|---|

| MFCA – general | ISO 14051 – specific |

| • What is the current knowledge of MFCA in practice?• What do organisations see as the anticipated benefits associated with MFCA activities?• What are the costs associated with MFCA implementation?• What are the barriers to MFCA implementation by business?• Under what conditions will MFCA result in tangible economic and environmental improvement?• What issues arise when applying MFCA across different industry sectors?• How does national culture affect the implementation and effectiveness of MFCA in organisations?• In cases where MFCA is abandoned, why was the decision made?• How do organisations select MFCA pilot projects?• To what extent do the results from pilot projects influence MFCA adoption decisions?• What organisational capabilities are required for successful MFCA implementation?• What functions are involved with MFCA in practice?• How is MFCA information used by managers in practice?• How is MFCA information communicated to different functions in large organisations?• To what extent does prior knowledge of material flows impact MFCA implementation decisions?• How can the professional accounting bodies best support MFCA tool development within the higher education curriculum? | • What is the current knowledge of ISO 14051 in practice?• How has the release of ISO 14051 impacted MFCA take-up by business?• To what extent has the release of ISO 14051 changed managerial perceptions of MFCA in practice?• What are the perceived costs and benefits of implementing ISO 14051 relative to other environmental and information management systems?• To what extent do the actual benefits associated with ISO 14051 implementation by business correspond with the benefits that were expected? and To what extent does organisational context influence this association?• What was the effect of ISO 14051 on improving the observability of MFCA?• What do consultants see as the potential benefits and barriers to implementation of ISO 14051?• What role do consultancy firms play in the diffusion of ISO 14051 and MFCA to business?• How does organisational experience with other ISO standards influence ISO 14051 implementation?• How do organisations rate ISO 14051 relative to other, certified, ISO standards?• How useful do managers perceive the ISO 14051 standard to be in terms of readability, ease of understanding, examples, etc.?• What role is played by higher education institutions in promoting the development of disciplinary and transdisciplinary knowledge about MFCA through ISO 14051? |

This paper considers whether a new era for MFCA implementation and research has arisen with the catalyst being a new eco-efficiency tool, ISO 14051, an international Material Flow Cost Management Standard. With a focus on the first two stages of Rogers’ (2003) diffusion of innovation theory, knowledge and persuasion, his five characteristics in all innovations were applied in order to assess potential effectiveness of ISO 14051 as the catalyst for changing the take-up of MFCA. Based on the evidence examined the conclusion is that there appears to be high potential for rapid uptake of MFCA in practice and a rich agenda of research opportunities opened up by the introduction of the new ISO 14051 standard.

In terms of relative advantage over existing practice and consistency with existing organisational goals it is found that ISO 14051 as a guidance standard, by bringing together monetary and physical information as a foundation for efficiency measures, is likely to motivate adoption by managers and speed up MFCA diffusion in a cost-effective way. Familiarity of organisations with comparable ISO quality and environmental management standards, and associated terminology and concepts, will reduce complexity and could also ease managers into accepting MFCA with its potential for continuous improvement in environmental and monetary performance. The foundation in juxtaposing observable monetary measures and improved productivity could help increase MFCA's appeal to organisations, but little is known at this point. Finally, the potential for piloting MFCA within organisational functions and segments increases its trialability while keeping risk of unsuccessful trials to a minimum. The literature examined and arguments presented suggest MFCA is now well placed as an environmental management accounting tool to persuade take-up by managers.

In addition, a rich range of directions for future research on MFCA is identified. These can apply to MFCA generally, or ISO 14051 in particular. First is the feasibility of applying new research methods to gather evidence in a systematic manner and strengthen arguments for improving natural and monetary capital. Statistically based quantitative and longitudinal research into barriers and enablers of MFCA implementation are wholly absent at present. Second is the potential for theoretically driven projects. No theoretical foundations have so far been applied in research into the net benefits of MFCA thus providing an opportunity for inter-subjectively testable research into the applicability of individual and multiple theories. Finally there is potential to address new general MFCA and specific ISO 14051 research questions which are summarised in Table 1 for convenience.

With the developing processes of consideration, take-up or rejection of MFCA by companies over time, rich opportunities arise both for researchers and practitioners to understand better the tangible and intangible drivers and barriers, by industry, by sector, by culture and by size of organisation.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare not to have any conflict of interest.