Small and medium-sized entities (SMEs) represent more than 95% of companies worldwide and account for more than 65% of employment. As a move towards SME harmonization, in 2009 the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) issued the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) for SMEs. Due to the lack of studies on adoption of IFRS for SMEs, we analyze the relationship between macroeconomic factors and countries’ decision to adopt IFRS for SMEs. Based on a sample of 84 adopters and non-adopters of IFRS for SMEs, both developed and developing countries, we find evidence that countries without a national set of financial accounting standards for SMEs, with experience of applying IFRS and a common law legal system are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs. These results may be due to low transaction costs, the importance of having some knowledge of IFRS reporting given its complexity and belonging to IFRS based countries facilitating adoption of IFRS for SMEs. Additionally, we find that European Union (EU) member countries are less likely to adopt the standard. Knowledge of macroeconomic factors affecting the decision to adopt IFRS for SMEs is useful for the various entities that define international accounting harmonization, such as the IASB, regulators and international accounting firms, since this information can help them to promote worldwide adoption of the standard.

Las pequeñas y medianas empresas (pymes) representan más del 95% de las empresas de todo el mundo y contabilizan más del 65% del empleo. Como paso hacia la armonización de las pymes, en 2009 el International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) emitió las International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) para las pymes. Debido a la falta de estudios sobre la adopción de las IFRS por las pymes, analizamos la relación entre los factores macroeconómicos y la decisión de los países de adoptar las IFRS para las pymes. Con base en una muestra de 84 adoptantes y no adoptantes de las IFRS para las pymes, tanto países desarrollados como en vías de desarrollo, encontramos evidencia de que los países sin un conjunto nacional de normas de contabilidad financiera para las pymes, con experiencia en aplicar las IFRS y un sistema legal de derecho común son más propensos a adoptar las IFRS para las pymes. Estos resultados pueden deberse a los bajos costos de transacción y la importancia de tener cierto conocimiento de los informes IFRS dada su complejidad y pertenencia a los países basados en las IFRS, lo que facilita la adopción de las IFRS por las pymes. Además, encontramos que los países miembros de la Unión Europea (UE) tienen menos probabilidades de adoptar la norma. El conocimiento de los factores macroeconómicos que afectan a la decisión de adoptar las IFRS para las pymes es útil para las diversas entidades que definen la armonización contable internacional, como el IASB, los reguladores y las empresas contables internacionales ya que esta información puede ayudarlos a promover la adopción mundial de la norma.

Since the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) for small and medium entities (SMEs) was issued in 2009 for SMEs that do not require public accountability, by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), 85 countries have required or permitted its use for SMEs’ financial reporting. However, several countries have not adopted or have rejected its adoption (IASB, 2009a, 2016, 2017). As well as the effects of the adoption of IFRS for SMEs on the quality of financial reporting, it is important to know the institutional characteristics of countries that adopt the standard. Since IFRS for SMEs is not mandatory, the contribution of countries’ institutional characteristics to its adoption becomes an important issue.

SMEs represent more than 95 percent of companies worldwide and account for more than 65 percent of employment (IASB, 2009a; IFAC, 2010). SMEs make a great contribution to job creation, technological innovation and economic output both for developed and developing countries (Chen, 2006). For instance, in Europe, SMEs accounted for 67% of total employment in 2010 and in the period 2002–2010 SMEs created 85% of the new jobs in the European Union (EU) (European Commission, 2012). Besides, SMEs represent 99.8% of non-financial companies and generate 57.4% of value added (European Commission, 2016). In the case of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) countries, SMEs are the main businesses, the largest employers and their contribution to economic output is significant (APEC, 2009).

In view of the importance of SMEs and the use of IFRS for SMEs in so many countries, the main objective of this study is to analyze whether there is a relationship between institutional factors and the adoption of IFRS for SMEs. This may help answer the question of why a country has adopted IFRS for SMEs.

Before the IASB issued IFRS for SMEs, countries adopted either their own national financial accounting standards or full IFRS for SMEs. The IASB believes that adopting IFRS for SMEs enhances SMEs’ access to international finance through harmonized and high quality financial information (IASB, 2009a). IFRS for SMEs is based on full IFRS with modifications reflecting the needs of those using SMEs’ financial statements and cost-benefit considerations (IASB, 2015). IFRS for SMEs is a stand-alone document with 5 sections, with a significantly reduced number of disclosures of around 300, compared to the full IFRS of 3000 disclosures and with reduced guidance (Perera & Chand, 2015). However, the IASB does not have any member with a SMEs background and the major comments about the new standard did not come from users. This is an issue since it may not fulfil the needs of users, and access to international funds is a very remote possibility, especially for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (Perera & Chand, 2015). The main perception of users is that IFRS for SMEs is too similar to the full IFRS (Quagli & Paoloni, 2012), but full IFRS are a set of complex, onerous and costly standards for SMEs (Perera & Chand, 2015).

The issue of a set of macroeconomic factors influencing accounting standards and practices in a country has already been studied (Anghel, 2013; Elliot & Elliot, 2013; Gray & Radebaugh, 2002; Nobes & Parker, 2000; Nobes, 1998). Several studies analyze the macroeconomic factors influencing their adoption for the consolidated financial statements of listed companies (Archambault & Archambault, 2009; Clements, Neill, & Stovall, 2010; Hope, Jin, & Kang, 2006; Lasmin, 2011; Ramanna & Sletten, 2014; Ritsumeikan, 2011; Shima & Yang, 2012; Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013). However, as far as we know, only Kaya and Koch (2015) study IFRS for SMEs by analysing the relation of macroeconomic factors with adoption at a country level. Most studies on IFRS for SMEs are about stakeholders’ perception of the costs and benefits of adoption (Albu et al., 2013; Kılıç, Uyar, & Ataman, 2014; Litjens & Bissessur, 2012; Uyar & Güngörmüş, 2013). Kaya and Koch (2015) study countries that have adopted IFRS for SMEs in 2013 and concluded that countries most likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs are those not capable of issuing their own set of financial accounting standards, those where full IFRS are applied for non-listed companies and those with a relatively low quality of governance institutions.

One important motivation is the lack of studies on adoption of IFRS for SMEs. It is important to study adoption of IFRS for SMEs for private companies that issue individual financial statements. Another motivation is to highlight the factors that could influence the adoption of IFRS for SMEs at a country level and not just at a microeconomic level. Besides, since IFRS for SMEs is not mandatory according to any supranational organization, the contribution of countries’ institutional characteristics to their adoption becomes an important issue to study.

Our sample includes 84 countries that have and have not adopted IFRS for SMEs at the end of 2015. We use a logit regression to examine whether institutional factors influence a country's decision to adopt IFRS for SMEs. We obtain information on the adoption status of each country from the IASB profile webpage (for instance, if the country has or has not adopted IFRS for SMEs and which set of accounting standards are in use). We study the following institutional factors: education, the availability of a national set of financial accounting standards for SMEs, familiarity with IFRS, legal system, foreign aid, quality of the national financial accounting standards and the relationship between accounting standards and tax rules. We could add more institutional factors, but as pointed out by Isidro, Nanda, and Wysocki (2016), adding more factors adds little incremental explanatory power. We expected that countries are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs if they have a higher education level, have no national set of financial accounting standards for SMEs, are more familiar with the application of IASB standards, have a common law legal system, are subject to a foreign aid programme, have a lower quality of national financial accounting standards and have a weak relationship between accounting and taxation. We also perform several robustness tests, for instance, measuring differently some of the independent variables.

The main results indicate that a country is more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs if it has no specific set of national financial accounting standards, if the legal system is common law and if it has more experience and familiarity with using IFRS. However, there is no evidence that the education level, foreign aid, quality of the national financial accounting standards and the relationship between accounting and taxation is related with the decision to adopt IFRS for SMEs. Because the European Union (EU) has not adopted IFRS for SMEs, unlike adoption of full IFRS, we study the influence of a country being a member of the EU. We find that those countries are less likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs, mainly because it would be necessary to make major changes in IFRS for SMEs to comply with the accounting directive (Kaya & Koch, 2015).

This study makes several contributions. One contribution is that we show that macroeconomic factors can influence the adoption of IFRS by SMEs. Another contribution is that we extend the results of Kaya and Koch (2015), regarding the year of study and the variables used. Moreover, the study includes many developed and developing countries, with many similarities, compared to studying full IFRS, due to the type of companies (small ones, preparing mainly individual financial statements, without complex transactions and organizational structures and non-listed). Understanding whether institutional factors are associated with the adoption of IFRS for SMEs is useful not only for researchers but also for accounting standards setters, governments, financial market regulators, investors, preparers, and most importantly, for the IASB, which can use our findings to promote more effectively the adoption of IFRS for SMEs, or even change the standard.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section two presents a literature review and hypotheses. The third section presents the sample and the regression model. The fourth section discusses the results. The fifth section presents the conclusions and the limitations of the study.

Literature review and development of hypothesesBecause of the growing internationalization of economic trade and globalization of businesses and financial markets, national financial accounting standards could no longer satisfy the needs of users (Barth, 2008; Judge, Li, & Pinsker, 2010; Kılıç et al., 2014; Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006). The importance of having a harmonized set of accounting standards not only for listed companies but also for non-listed ones has grown, and therefore the IASB developed, besides full IFRS, the IFRS for SMEs. The project began in 2003 and IFRS for SMEs was published on 9 July 2009. IASB thinks that as IFRS for SMEs harmonizes and enhances the quality of financial statements, this will facilitate access to international finance (IASB, 2009a).

Francis, Khurana, Martin, and Pereira (2008) find evidence that microeconomic and macroeconomic factors influence the company's voluntary adoption. They show that microeconomic factors are more important than macroeconomic ones in developed countries and the opposite occurs in developing countries. This conclusion can reduce the strength of the influence of institutional factors on adoption of IFRS for SMEs (or full IFRS) when the study includes both developed and developing countries, but only when that option is available. However, the adoption of IFRS for SMEs could be used as a mechanism to reduce conflicts of interest between tax authorities and creditors and SMEs management (Kolsi & Zehri, 2013). Coercive isomorphism as a mechanism to support institutional isomorphism can help to explain adoption of IFRS for SMEs, by the formal or informal pressure to adopt by some organizations (Judge et al., 2010; Kossentini & Othman, 2014). Another form of isomorphism is normative isomorphism, which refers to collective values that standardize thoughts within institutional environments, and this could lead accounting professionals to put pressure in favour of adopting IFRS for SMEs (Judge et al., 2010; Kossentini & Othman, 2014).

Macroeconomic factors affect and explain accounting practices, and these include the history of a colonial country, the stage of its economic development, financial system, political system, legal system, educational system and culture, among other factors (Anghel, 2013; Elliot & Elliot, 2013; Gray & Radebaugh, 2002; Nobes & Parker, 2000; Nobes, 1998). For Alhashim and Arpan (1992), the most important factors influencing accounting are economic, social, the legal system, culture and political system. Here, several studies focus on the microeconomic factors related to firm characteristics that affect adoption of IFRS (Affes & Callimaci, 2007; Francis et al., 2008; Leuz & Verrecchia, 2000; Murphy, 1999), while others focus on macroeconomic factors that could be determinants of IFRS adoption (Archambault & Archambault, 2009; Clements et al., 2010; Hope et al., 2006; Lasmin, 2011; Ramanna & Sletten, 2014; Shima & Yang, 2012; Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013).

Based on previous studies about the determinant factors of IFRS adoption and on the specificities of IFRS for SMEs, the factors chosen are education level, the availability of a national set of financial accounting standards for SMEs, familiarity with IFRS, the legal system, foreign aid, the quality of national financial accounting standards and the relationship between accounting standards and tax rules (Archambault & Archambault, 2009; Delcoure & Huff, 2015; Felski, 2015; Johnson, 2011; Judge et al., 2010; Kaya & Koch, 2015; Kolsi & Zehri, 2013; Kossentini & Othman, 2014; Lasmin, 2011; Ramanna & Sletten, 2009; Shima & Yang, 2012; Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013).

Education levelGermon, Meek and Mueller (1987) found a positive relationship between education level and the competence of accountants, and Radebaugh (1975) and Mueller (1968) revealed the influence of education level on accounting practices. Financial accounting standards are less developed when accountants have little experience and knowledge of complex accounting issues, and if the professional body is developed and strong it is more likely to develop a sophisticated and rigorous set of financial accounting standards (Ding, Hope, Jeanjean & Stolowy, 2007). Indeed, accountants’ lack of training in applying IFRS for SMEs is one of the main obstacles to implementing the standard (Albu et al., 2013; Albu, Albu, & Alexander, 2014; Kılıç et al., 2014; Perera & Chand, 2015; Roberts & Sian, 2006; Uyar & Güngörmüş, 2013). Besides, the preparers of European countries say that IFRS for SMEs is not suitable in a European context because of the difficulty in applying the standard, since it is too similar to the full IFRS despite efforts to simplify it (Quagli & Paolini, 2012). Full IFRS are very complex and require deep knowledge not only of accounting but also of finance (Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013). Education level could be used as a proxy for normative isomorphism, this being a mechanism that supports institutional isomorphism (Judge et al., 2010; Kossentini & Othman, 2014).

Although there is no specific measure of accountants’ level of knowledge (Judge et al., 2010), Carus (2002) and Choi and Meek (2008) showed a relationship between education level and accountants’ expertise, and this is used by Archambault and Archambault (2009), Shima and Yang (2012) and Zeghal and Mhedhbi (2006) in their studies of the influence of macroeconomic factors on adoption of full IFRS.

We expect that countries with more education are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs, because preparers of financial statements and stakeholders will be able to read, understand and apply IFRS for SMEs. This is shown for full IFRS adoption by Archambault and Archambault (2009), Judge et al. (2010) and Shima and Yang (2012) and in the case of developing countries by Kolsi and Zehri (2013), Zeghal and Mhedhbi (2006) and Zehri and Chouaibi (2013). However, in the only study of IFRS for SMEs, no relationship is found between education level and the likelihood of adopting IFRS for SMEs (Kaya & Koch, 2015). Thus, the first hypothesis is:H1 Countries with higher education levels are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs.

Issuing IFRS for SMEs was the IASB's answer to countries that were looking for a simplified version of the full IFRS (Jermakowicz & Epstein, 2010), mainly countries which did not have an accounting system for those companies and therefore could adopt that financial accounting standard without incurring costs in developing their own standards (Chua & Taylor, 2008; Irvine, 2008; Pacter, 2009) and considering full IFRS adoption too complex for SMEs (Dang-Duc, 2011; IASB, 2009a; Quagli & Paoloni, 2012; Tyrrall, Woodward, & Rakhimbekova, 2007). In EU countries, companies have to prepare at least individual financial statements in accordance with the accounting directives (the fourth and seventh ones), IFRS for SMEs being optional. Moreover, IFRS for SMEs does not serve the objective of reducing the administrative burden and it is incompatible with the accounting directives. Besides, in some countries financial accounting is used for tax purposes and dividends (Quagli & Paolini, 2012). For example, countries such as Lebanon, Slovakia, Austria and Russia think that SMEs should prepare financial statements for tax purposes (Perera & Chand, 2015). All these could imply changing the law or even changing IFRS for SMEs.

Thus, we expect that countries without their own set of financial accounting standards for SMEs are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs. Chamisa (2000) found that countries are less likely to adopt the financial accounting standards of another country, and countries with their own national financial accounting standards would be less likely to adopt another set of standards because they may lose their power in establishing standards (Johnson, 2011; Kaya & Koch, 2015). Therefore, the following hypothesis is:H2 Countries without a national set of financial accounting standards for SMEs are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs.

Both full IFRS and IFRS for SMEs are principles based, IFRS for SMEs being a simplified version of the full IFRS. Even if IFRS for SMEs is less complex than full IFRS, it is still too complex for SMEs (Perera & Chand, 2015***). Therefore, we can conclude that countries that have adopted full IFRS are more experienced and familiar with implementing IFRS for SMEs. For instance Hong Kong, Malaysia, Chile and Uruguay have adopted IFRS for SMEs, but with a few modifications, and they also use full IFRS for listed companies. On the other hand, Bolivia, China, Egypt, Indonesia, India and Japan have adopted neither full IFRS nor IFRS for SMEs. This could lead us to expect that countries that do not have any familiarity with full IFRS will be less likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs. It is the first time this factor has been studied, and the third hypothesis is:H3 Countries more familiar with applying IASB standards are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs.

Being part of a certain group of countries is a factor that can influence an accounting system (Nobes, 1998). Legal systems are divided in common law and code law and this is a factor influencing countries’ accounting standards (Doupnik & Slater, 1995; Nobes, 1983). The common law system is based on English law and is shaped by precedents from judicial decisions (including the United Kingdom (UK) and its former colonies such as the United States (US), Canada, Australia, and India). The main governance model is the financial market, the main users of financial accounting data are investors and creditors and the State is not a privileged user. The code law system originated in Roman law, using statutes and comprehensive codes (including France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, Netherlands, Italy; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, 1998). The main users of financial accounting figures are creditors and the State is greatly involved in the process of setting standards. In particular, banks are the main creditors. The IFRS are the result of the common law legal system (Botzem & Quack, 2009), and this could influence IFRS adoption, as corroborated by the findings of Felski (2015), Kolsi and Zehri (2013)Kossentini and Othman (2014), Shima and Yang (2012) and Zehri and Chouaibi (2013). However, Hope et al. (2006) did not find any influence of the legal system on IFRS adoption. Kaya and Koch (2015) find the same influence of the legal system on adoption of IFRS for SMEs. Hence, our fourth hypothesis is:H4 Countries with a common law legal system are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs.

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) help developing countries with financing difficulties by lending money, and providing technical and training support in applying the best practices in several areas, namely in financial reporting (Irvine, 2008; Neu & Gomez, 2006; Neu & Ocampo, 2007). The World Bank emphasises the importance of financial reporting in its development strategy for better financial markets and accountability (Kaya & Koch, 2015). One of the long-term benefits of adopting IFRS for SMEs is better lending conditions from the IMF and the World Bank (Gordon, Loeb, & Zhu, 2012). As IASB financial accounting standards are known worldwide, countries subject to a foreign aid programme have an incentive to adopt them (Mir & Rahaman, 2005). Romania, Jordan, Egypt, Kazakhstan, Pakistan and Zimbabwe are just a few examples of countries that the World Bank, the IMF, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) or the Asian Development Bank (ADB) demanded IFRS adoption for lending money (Al-Akra, Ali, & Marashdeh, 2009; Albu, Albu, Bunea, Calu, & Girbina, 2011; Ashraf & Ghani, 2005; Chamisa, 2000; Hassan, 2008; Mir & Rahaman, 2005; Tyrrall et al., 2007). The World Bank Reports on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSC) in Bosnia and Herzegovina (2010), Mauritius (2011) and Slovenia (2014) recommend the use of IFRS for SMEs. Foreign aid can be seen as a proxy for coercive isomorphism, which is one mechanism of institutional isomorphism (Judge et al., 2010; Kossentini & Othman, 2014). Judge et al. (2010), Kossentini and Othman (2014) and Lasmin (2011) showed the positive influence of foreign aid on full IFRS adoption. However Ramanna and Sletten (2014) and Kaya and Koch (2015) did not find any evidence of that influence, and Archambault and Archambault (2009) found a negative influence of foreign aid on full IFRS adoption. These mixed results lead us to the fifth hypothesis:H5 Countries subject to a foreign aid programme are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs.

The objective of changing the set of financial accounting standards is to improve financial reporting (Daske & Gebhardt, 2006). Knowing this, Ramanna and Sletten (2009) and Kaya and Koch (2015) show that in countries where the quality of financial accounting standards is high IFRS adoption is less likely, since the cost of changing is high. Examples of countries with high quality national financial accounting standards are Australia, France, Germany, Canada and the US, and these have not so far adopted IFRS for SMEs (Perera & Chand, 2015). Since the main users of SMEs’ financial reporting are the government and banks, managers do not like to allocate resources to the accounting system, and the latter are not satisfied with the quality of financial reporting. Albu et al. (2013) find evidence for the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Turkey, and Kılıç et al. (2014) for Turkey, that adoption of IFRS for SMEs would improve the transparency and quality of accounting information. Thus the sixth hypothesis is:H6 Countries with high quality national financial accounting standards are less likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs.

In several countries the main user of SMEs’ financial reporting is considered to be the tax authority (Al-Akra et al., 2009; Albu et al., 2013, 2014, 2011; Jermakowicz & Gornik-Tomaszewski, 2006; Perera & Chand, 2015). Nevertheless, the main purpose of IFRS for SMEs is not to satisfy tax authority needs (IASB, 2009b, 2015). In some countries, SMEs have to comply with some tax rules in their financial reporting and full IFRS adoption would be an administrative burden (Albu et al., 2013; Bohušová & Blašková, 2012). When standard setters are dependent on the government and taxes rules are accounting based, the focus of accounting standards is on taxation and compliance (Felski, 2015). The control and legitimacy of the standard setter in financial reporting in Romania prevents IFRS adoption (Albu et al., 2014). The main reason for IFRS adoption in Brazil in 2007 was the reduction of the tax authority's influence on financial reporting (Rodrigues, Schmidt & Dos Santos, 2012). Phuong and Nguyen (2012) point out that the strict link between taxation and accounting in Vietnam may limit the success of IFRS adoption. This is also one of the main obstacles to IFRS adoption in Tunisia (Trabelsi, 2010). Felski (2015), Kossentini and Othman (2014), Shima and Yang (2012) and Kaya and Koch (2015) found evidence that the importance of tax rules negatively influences IFRS adoption. This leads to our seventh hypothesis:H7 Countries with a strong relationship between accounting standards and tax rules are less likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs.

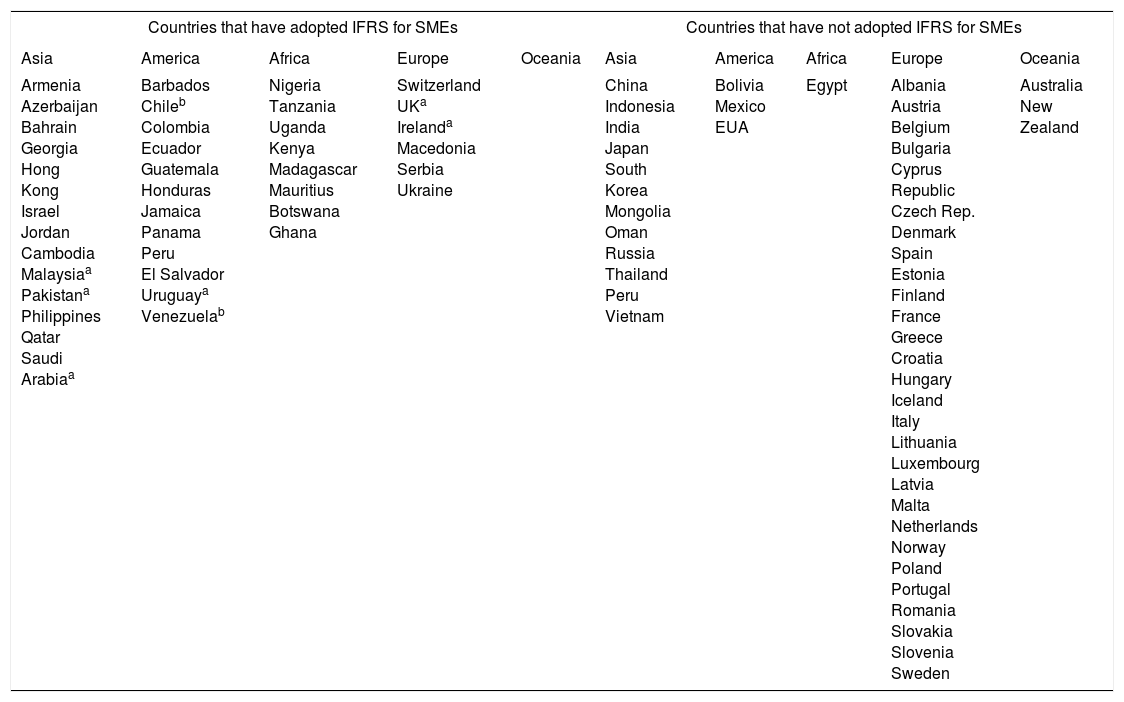

We use the IASB website that contains the country profiles of IFRS and IFRS for SEMs adoption (IASB, 2016). Starting from 143 countries, our final sample is composed of 84 countries spread over five continents for which information is fully available. The sample includes two groups of countries, one group of 39 countries that have adopted IFRS for SMEs with or without changes, and another group of 45 countries, non-adopters of IFRS for SMEs until March 2016. Table 1 shows the list of countries, and most countries adopting IFRS for SMEs are from Asia (13 countries), America (12 countries) and Africa (8 countries). The least adopting countries are from Europe (29 countries). The only two countries from Oceania included are non-adopters. Nevertheless, the adoption of IFRS for SMEs is dynamic, so the number of adopters increases over time. The data on institutional factors are gathered from the World Bank, IASB (2016), CIA World Factbook, The Global Competitiveness Report by the World Economic Forum (WEF) (2011) and PwC (2011) as shown in Table 2. The information on IFRS for SMEs adoption, national set of financial accounting standards and familiarity with IFRS variables is from 2016, for education level and foreign aid it is based on an average of 2005–2009, for quality of national financial accounting standards it is 2010 and for the relationship between accounting standards and tax rules it is 2011 as presented in Table 2.

Sample of countries by region.

| Countries that have adopted IFRS for SMEs | Countries that have not adopted IFRS for SMEs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | America | Africa | Europe | Oceania | Asia | America | Africa | Europe | Oceania |

| Armenia Azerbaijan Bahrain Georgia Hong Kong Israel Jordan Cambodia Malaysiaa Pakistana Philippines Qatar Saudi Arabiaa | Barbados Chileb Colombia Ecuador Guatemala Honduras Jamaica Panama Peru El Salvador Uruguaya Venezuelab | Nigeria Tanzania Uganda Kenya Madagascar Mauritius Botswana Ghana | Switzerland UKa Irelanda Macedonia Serbia Ukraine | China Indonesia India Japan South Korea Mongolia Oman Russia Thailand Peru Vietnam | Bolivia Mexico EUA | Egypt | Albania Austria Belgium Bulgaria Cyprus Republic Czech Rep. Denmark Spain Estonia Finland France Greece Croatia Hungary Iceland Italy Lithuania Luxembourg Latvia Malta Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal Romania Slovakia Slovenia Sweden | Australia New Zealand | |

Measurement and data source.

| Panel A: Dependent variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable name | Variable label | Measurement |

| IFRSsme | IFRS for SMEs | Variable that takes the value of 1 if the country adopts IFRS for SMEs by March 2016 and 0 otherwise. |

| Panel B: Independent variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable name | Variable label | Measurement | Data source | Expected sign |

| EDU | Education level | Enrolment at university (average in the period 2005–2009 of students enrolled at university in the total population of that age). | World Bank. | + |

| NGAAP | National set of financial accounting standards for SMEs | 1 if the country has a set of financial accounting standards for SMEs and 0 otherwise. | IASB (2016). | − |

| IFRS | Familiarity with full IFRS | 1 if full IFRS are permitted or required for listed companies and 0 otherwise. | IASB (2016). | + |

| LAW | Legal system | 1 if the country has a common law system and 0 otherwise. | CIA World Factbook, or if not available, from the La Porta et al. (1998) classification. | + |

| AID | Foreign aid | Foreign aid in gross domestic product (average for the period 2005–2009). | World Bank. | + |

| QUA | Quality of the national financial accounting standards | Quality of auditing and accounting standards on a scale from 1 to 7. | The Global Competitiveness Report (WEF, 2011). | − |

| TAX | Relationship between accounting standards and tax rules | 1 if taxable income is based on accounting income and 0 otherwise. | PwC (2011). | − |

| LGDP | Log of GDP | Log of gross domestic product. | World Bank. | − |

| DEV | Development of a country | 1 if the country is developed and 0 otherwise. | World Bank. | − |

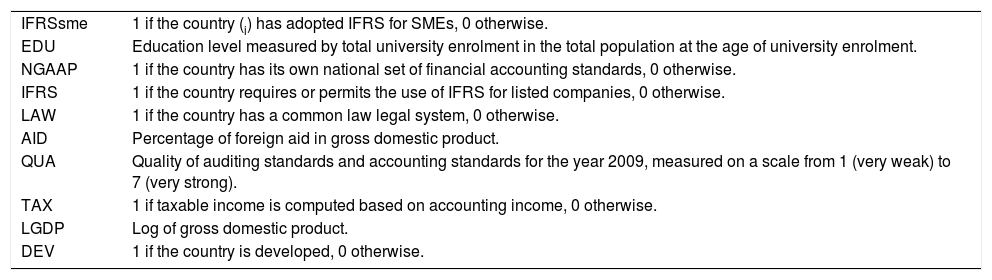

We use the following logit model to test our hypotheses since the dependent variable is dichotomous. The model was used in several studies on IFRS adoption (Archambault & Archambault, 2009; Clements et al., 2010; Hope et al., 2006; Kaya & Koch, 2015; Lasmin, 2011; Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013):

where| IFRSsme | 1 if the country (i) has adopted IFRS for SMEs, 0 otherwise. |

| EDU | Education level measured by total university enrolment in the total population at the age of university enrolment. |

| NGAAP | 1 if the country has its own national set of financial accounting standards, 0 otherwise. |

| IFRS | 1 if the country requires or permits the use of IFRS for listed companies, 0 otherwise. |

| LAW | 1 if the country has a common law legal system, 0 otherwise. |

| AID | Percentage of foreign aid in gross domestic product. |

| QUA | Quality of auditing standards and accounting standards for the year 2009, measured on a scale from 1 (very weak) to 7 (very strong). |

| TAX | 1 if taxable income is computed based on accounting income, 0 otherwise. |

| LGDP | Log of gross domestic product. |

| DEV | 1 if the country is developed, 0 otherwise. |

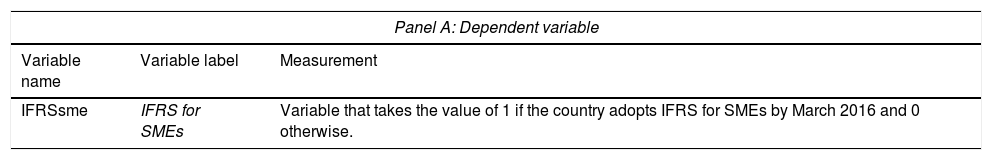

To measure the adoption of IFRS for SMEs we use a dichotomous variable that takes the value of 1 if the country adopts IFRS for SMEs and 0 otherwise (Archambault & Archambault, 2009; Clements et al., 2010; Hope et al., 2006; Lasmin, 2011; Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013). Some studies add to the variable if the country has adopted IFRS voluntarily or as mandatory and if for all companies or just for some (Judge et al., 2010; Kossentini & Othman, 2014; Ramanna & Sletten, 2009, 2014; Shima & Yang, 2012). Both measures have limitations, since the reason for adopting IFRS for SMEs is different between countries and over time. In this study we consider adoption of IFRS for SMEs both if adoption is voluntary or mandatory as at March 2016, knowing that IFRS for SMEs is mandatory for only two countries in the sample. Most previous studies use the Deloitte IASplus database in the classification of full IFRS adopters and non-adopters (Archambault & Archambault, 2009; Clements et al., 2010; Hope et al., 2006; Lasmin, 2011; Ramanna & Sletten, 2014; Shima & Yang, 2012; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013). Since the information on IFRS for SMEs is not updated, we use the country profile information of the IASB. The variables of the study are summarized in Table 2.

The year 2009 is used as the reference period to measure the explanatory variables in the decision to adopt IFRS for SMEs, since IFRS for SMEs was issued by IASB in July 2009 (IASB, 2009a). Whenever possible, the explanatory variables are measured using data from 2009 or the average from the previous years (2005–2009). All the explanatory variables are macroeconomic and none are microeconomic.

The role of education in the adoption of IFRS is confirmed by several studies (Archambault & Archambault, 2009; Judge et al., 2010; Kolsi & Zehri, 2013; Shima & Yang, 2012; Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013). Education level could be measured by literacy rates (Archambault & Archambault, 2009; Shima & Yang, 2012; Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013). Other ways to measure education level are the percentage of primary school enrolment (Felski, 2015), the average enrolment in secondary schools as a percentage of the total population (Judge et al., 2010; Lasmin, 2011) and total enrolment at university, expressed as a percentage of the total population at the age of university enrolment (Kaya & Koch, 2015; Kossentini & Othman, 2014). In this study, we use the last since most professional accountants should have a first degree and we expect a positive influence on adoption of IFRS for SMEs.

Information about the existence of a country's own national financial accounting standards for SMEs is gathered from the IASB profile for each country. We expect a negative influence on adoption of IFRS for SMEs.

The first set of standards issued by the IASB were the IFRS, mainly to satisfy investors’ needs, having been adopted by 119 countries especially for listed companies (Jorissen, Lybaert, & Van de Poel, 2006; Quagli & Paoloni, 2012). This data is obtained from the IASB profile. We expect a positive influence on adoption of IFRS for SMEs if countries permit or require the use of IFRS for listed companies.1

The type of legal system is usually treated as a dichotomous variable that takes the value of 1 for common law countries and 0 for code law countries (Archambault & Archambault, 2009; Hope et al., 2006; Kaya & Koch, 2015; Shima & Yang, 2012; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013). In this study we use the same measure and expect a positive influence on adoption of IFRS for SMEs.

Foreign aid is measured as a percentage of loans in gross domestic product and this could influence IFRS for SMEs adoption (Lasmin, 2011; World Bank, 2015). This measure is used by Archambault and Archambault, (2009), Felski (2015), Judge et al. (2010) and Lasmin (2011) and is gathered from the World Bank (2016). We expect a positive influence of foreign aid on adoption of IFRS for SMEs.

To measure the quality of the national financial accounting standards we use the index of The Global Competitiveness Report 2009–2010 (Bohušová & Blašková, 2012; Kaya & Koch, 2015). We expect a negative influence of this variable on adoption of IFRS for SMEs.

The relationship between accounting standards and tax rules is measured by a binary variable that takes the value of 1 if taxable income is based on accounting income and 0 otherwise (Kaya and Koch, 2015; Kossentini and Othman, 2014). This information is obtained from PwC (2011). The influence expected is that the closer the relationship between accounting standards and tax rules the less likely is adoption of IFRS for SMEs.

This study uses two control variables, one for controlling the size of the country, which is the log of gross domestic product, and another to control for country development, which is the country's level of development (Felski, 2015; Hope et al., 2006; Judge et al., 2010; Kaya & Koch, 2015). Economic factors are important determinants of the development of accounting systems (Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006). One way to control for the size of the country could be to use adopter and non-adopter countries of the same size, as do Zeghal and Mhedhbi (2006). Hope et al. (2006) use gross domestic product per capita. Kaya and Koch (2015) use the log of gross domestic product. This study uses the log of gross domestic product for the period 2005–2009 (World Bank, 2016), expecting a negative relation with adoption of IFRS for SMEs.

To compare countries, some studies include only developing countries in their samples (Kolsi & Zehri, 2013; Lasmin, 2011; Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013) or emergent countries (Delcoure & Huff, 2015; Kossentini & Othman, 2014). Some of the institutional factors studied are likely to be more applicable to developing countries than to developed ones. Because this study includes several types of countries it is necessary to control for this, and a binary variable is used with the value of 1 for developed countries and 0 otherwise and a negative relation is expected with adoption of IFRS for SMEs. This information is gathered from the World Bank (2015).

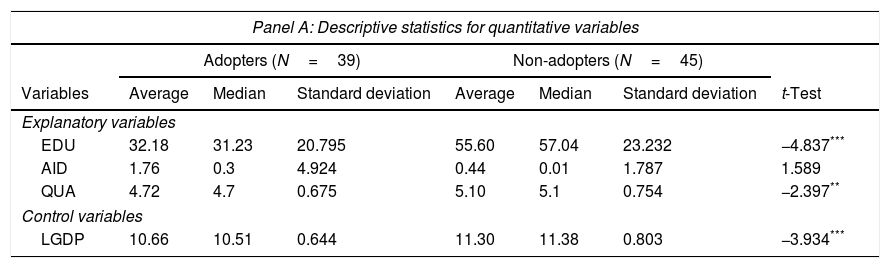

Results and findingsDescriptive statisticsThe descriptive statistics are presented in Table 3. The parametric t-test (and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney) of difference in means across adopters and non-adopters rejects the null hypothesis of no difference at the 10% level (excluding the variables of foreign aid (AID) and relationship between accounting standards and tax rules (TAX)). The mean of education level (EDU), quality of the national financial accounting standards (QUA) and size of the country (LGDP) is lower in adopters than in non-adopters, which confirms expectations. The frequency of the use of full IFRS for listed companies (IFRS) is lower in non-adopter countries as well as the availability of a national set of financial accounting standards (NGAAP). More countries have a common law legal system than a code law legal system (LAW).

Descriptive statistics.

| Panel A: Descriptive statistics for quantitative variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adopters (N=39) | Non-adopters (N=45) | ||||||

| Variables | Average | Median | Standard deviation | Average | Median | Standard deviation | t-Test |

| Explanatory variables | |||||||

| EDU | 32.18 | 31.23 | 20.795 | 55.60 | 57.04 | 23.232 | −4.837*** |

| AID | 1.76 | 0.3 | 4.924 | 0.44 | 0.01 | 1.787 | 1.589 |

| QUA | 4.72 | 4.7 | 0.675 | 5.10 | 5.1 | 0.754 | −2.397** |

| Control variables | |||||||

| LGDP | 10.66 | 10.51 | 0.644 | 11.30 | 11.38 | 0.803 | −3.934*** |

| Panel B: Descriptive statistics for qualitative variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adopters (N=39) | Non-adopters (N=45) | ||||

| Variables | Frequency | Frequency | t-Test | U-test | |

| Independent variables | |||||

| NGAAP | 1 | 36% | 93% | −6.646*** | −5.536*** |

| 0 | 64% | 7% | |||

| IFRS | 1 | 95% | 82% | 1.865* | −1.775* |

| 0 | 5% | 18% | |||

| LAW | 1 | 41% | 13% | 2.920*** | −2.862*** |

| 0 | 59% | 87% | |||

| TAX | 1 | 87% | 80% | 0.885 | −0.875 |

| 0 | 13% | 20% | |||

| Control variables | |||||

| DEV | 1 | 23% | 62% | −3.912*** | −3.583*** |

| 0 | 77% | 38% | |||

Significant at 0.01.

Notes: EDU is education level measured by total enrolments at university. NGAAP is 1 if the country has its own national set of financial accounting standards, 0 otherwise. IFRS is 1 if the country requires or permits the use of IFRS for listed companies, 0 otherwise. LAW is 1 if the country has a common law legal system, 0 otherwise. AID is foreign aid as a percentage of gross domestic product. QUA is the quality of auditing standards and accounting standards. TAX is 1 if taxable income is computed based on accounting income, 0 otherwise. LGDP is the log of gross domestic product. DEV is 1 if the country is developed, 0 otherwise.

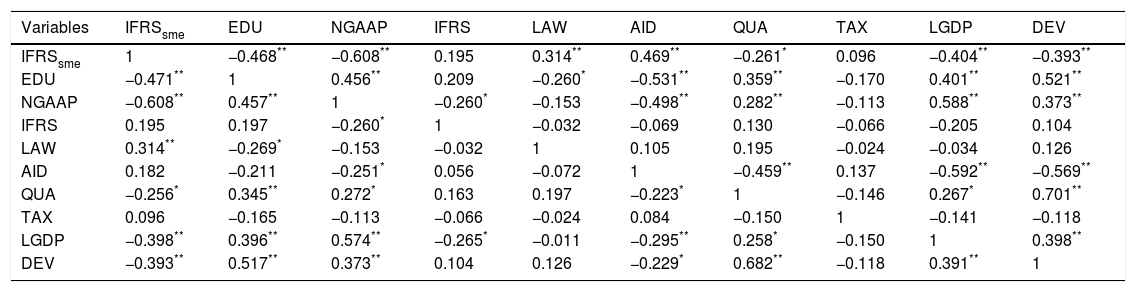

Table 4 show the Pearson correlations below the diagonal and the Spearman correlations above the diagonal. This correlation matrix is to examine whether multicollinearity is a potential issue. All the correlations are below 0.80. To confirm that collinearity does not affect our results we performed a multicollinearity test as shown in Table 5. We find that all variance inflation factors (VIF) are below the standard acceptable level of three (Judge, Hill, Griffiths, Lutkepohl, & Lee, 1988). Even though there is no statistical correlation among the macroeconomic factors, Isidro et al. (2016) state that many of the macroeconomic factors could be economically correlated. To avoid having two or more factors explaining the same and to identify them we could perform a principal factor analysis. To test if principal factor analysis is suitable we perform the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test and the value is 0.526, meaning that the correlation between the variables is weak and therefore the principal component analysis is not suitable. We ran the regression adding the variables one by one and in a different sequence. Two possible variables could be eliminated, AID and TAX, but the results are very similar to those we present.

Pearson and Spearman correlations.

| Variables | IFRSsme | EDU | NGAAP | IFRS | LAW | AID | QUA | TAX | LGDP | DEV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFRSsme | 1 | −0.468** | −0.608** | 0.195 | 0.314** | 0.469** | −0.261* | 0.096 | −0.404** | −0.393** |

| EDU | −0.471** | 1 | 0.456** | 0.209 | −0.260* | −0.531** | 0.359** | −0.170 | 0.401** | 0.521** |

| NGAAP | −0.608** | 0.457** | 1 | −0.260* | −0.153 | −0.498** | 0.282** | −0.113 | 0.588** | 0.373** |

| IFRS | 0.195 | 0.197 | −0.260* | 1 | −0.032 | −0.069 | 0.130 | −0.066 | −0.205 | 0.104 |

| LAW | 0.314** | −0.269* | −0.153 | −0.032 | 1 | 0.105 | 0.195 | −0.024 | −0.034 | 0.126 |

| AID | 0.182 | −0.211 | −0.251* | 0.056 | −0.072 | 1 | −0.459** | 0.137 | −0.592** | −0.569** |

| QUA | −0.256* | 0.345** | 0.272* | 0.163 | 0.197 | −0.223* | 1 | −0.146 | 0.267* | 0.701** |

| TAX | 0.096 | −0.165 | −0.113 | −0.066 | −0.024 | 0.084 | −0.150 | 1 | −0.141 | −0.118 |

| LGDP | −0.398** | 0.396** | 0.574** | −0.265* | −0.011 | −0.295** | 0.258* | −0.150 | 1 | 0.398** |

| DEV | −0.393** | 0.517** | 0.373** | 0.104 | 0.126 | −0.229* | 0.682** | −0.118 | 0.391** | 1 |

Significant at 0.05.

Notes: Pearson correlation coefficients are shown below the diagonal and the Spearman correlation coefficients are shown above the diagonal. IFRSsme is 1 if the country has adopted IFRS for SMEs by March 2016, 0 otherwise. EDU is education level measured by total enrolments at university. NGAAP is 1 if the country has its own national set of financial accounting standards, 0 otherwise. IFRS is 1 if the country requires or permits the use of IFRS for listed companies, 0 otherwise. LAW is 1 if the country has a common law legal system, 0 otherwise. AID is foreign aid as a percentage of gross domestic product. QUA is the quality of auditing standards and accounting standards. TAX is 1 if taxable income is computed based on accounting income, 0 otherwise. LGDP is the log of gross domestic product. DEV is 1 if the country is developed, 0 otherwise.

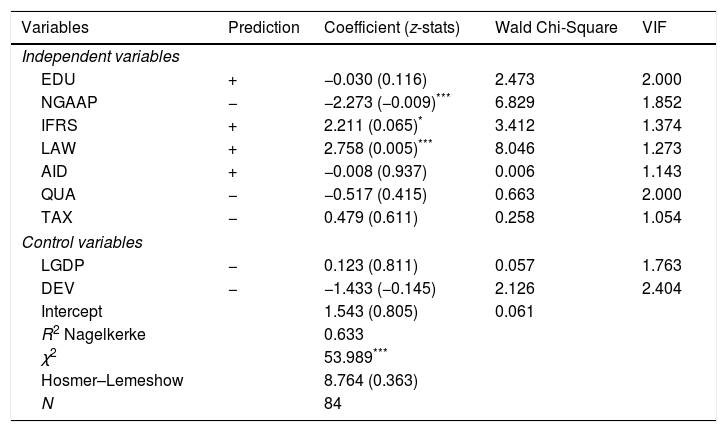

Logit regression results of adoption of IFRS for SMEs.

| Variables | Prediction | Coefficient (z-stats) | Wald Chi-Square | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | ||||

| EDU | + | −0.030 (0.116) | 2.473 | 2.000 |

| NGAAP | − | −2.273 (−0.009)*** | 6.829 | 1.852 |

| IFRS | + | 2.211 (0.065)* | 3.412 | 1.374 |

| LAW | + | 2.758 (0.005)*** | 8.046 | 1.273 |

| AID | + | −0.008 (0.937) | 0.006 | 1.143 |

| QUA | − | −0.517 (0.415) | 0.663 | 2.000 |

| TAX | − | 0.479 (0.611) | 0.258 | 1.054 |

| Control variables | ||||

| LGDP | − | 0.123 (0.811) | 0.057 | 1.763 |

| DEV | − | −1.433 (−0.145) | 2.126 | 2.404 |

| Intercept | 1.543 (0.805) | 0.061 | ||

| R2 Nagelkerke | 0.633 | |||

| χ2 | 53.989*** | |||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow | 8.764 (0.363) | |||

| N | 84 | |||

Significant at 0.01.

Notes: EDU is education level measured by total enrolments at university. NGAAP is 1 if the country has its own national set of financial accounting standards, 0 otherwise. IFRS is 1 if the country requires or permits the use of IFRS for listed companies, 0 otherwise. LAW is 1 if the country has a common law legal system, 0 otherwise. AID is foreign aid as a percentage of gross domestic product. QUA is the quality of auditing standards and accounting standards. TAX is 1 if taxable income is computed based on accounting income, 0 otherwise. LGDP is the log of gross domestic product. DEV is 1 if the country is developed, 0 otherwise.

Table 5 presents the main results of the logit regression for the influence of macroeconomic factors on adoption of IFRS for SMEs. Adoption of IFRS for SMEs is explained by 63.3 percent by the model. The χ2 test is significant and we can conclude that the model is reliable. The same conclusion is reached by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, since we cannot reject the null hypotheses. The results show that countries without a national set of financial accounting standards, countries with a common law legal system and those familiar with IFRS are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs, which is in line with the second, third and fourth hypotheses, since the coefficients are statistically significant at least at a 10% level. However, the other coefficients are not statistically significant, meaning it is not possible to confirm the other hypotheses. That is, it is not possible to confirm that the education level influences the likelihood of adopting IFRS for SMEs (as in Kaya & Koch's (2015) study), that countries subject to a foreign aid programme are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs (as in the study by Hope et al. (2006) regarding IFRS), or that countries with high quality financial accounting standards and a strong relationship between accounting standards and tax rules are less likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs.

These results suggest that the most important institutional factors influencing the decision to adopt IFRS for SMEs are familiarity with, and experience of IFRS financial reporting, implying that the transition costs are lower and confirming the importance of having some experience of IFRS reporting due to its complexity and the need for thorough knowledge of accounting and finance. Since the IASB harmonization project is controlled by countries that have a common law legal system, naturally these countries are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs. If the country has no complete set of national financial accounting standards of its own, the adoption of IFRS for SMEs is understandable, as this avoids all the costs of developing a complete set of accounting standards, despite the likelihood of difficulty in application due to being too similar to full IFRS. We can conclude that education, the quality of national financial accounting standards and the relationship between accounting and tax are important factors, but for full IFRS adoption, as is pointed out by several studies, but not for adopting IFRS for SMEs, because countries usually decide to adopt full IFRS first. Not finding any relationship between foreign aid and adoption of IFRS for SMEs confirms the mixed results found for full IFRS adoption.

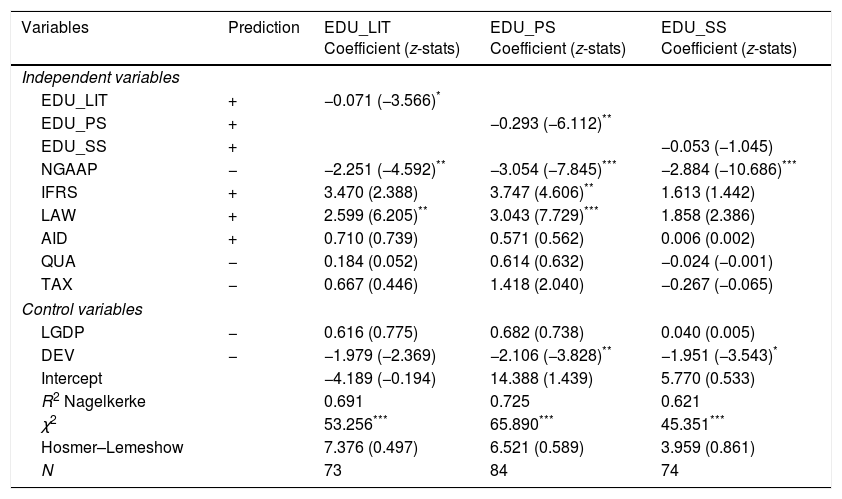

Robustness and additional testsEducation level could be measured using the average literacy rate for men and women aged 15 years or more (EDU_LIT) (Shima & Yang, 2012; Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013), the percentage of primary school enrolment (EDU_PS) (Felski, 2015) and the percentage of secondary school enrolment (EDU_SS) (Judge et al., 2010; Lasmin, 2011). Table 6 shows those results. The results are changed, measuring education level by the literacy rate (EDU_LIT) and percentage of primary school enrolment (EDU_PS). Education level reduces the likelihood of adopting IFRS for SMEs, since the coefficient is negative and statistically significant. This could be explained by the fact that highly educated professional accountants could themselves develop a set of financial accounting standards (Ding et al., 2007) and the lack of qualified accounting professionals lets them define a set of accounting standards, the easiest way being to adopt an established set of accounting standards such as IFRS for SMEs (Kossentini & Othman, 2014).

Logit regression results of adoption of IFRS for SMEs – different measures of education level.

| Variables | Prediction | EDU_LIT Coefficient (z-stats) | EDU_PS Coefficient (z-stats) | EDU_SS Coefficient (z-stats) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | ||||

| EDU_LIT | + | −0.071 (−3.566)* | ||

| EDU_PS | + | −0.293 (−6.112)** | ||

| EDU_SS | + | −0.053 (−1.045) | ||

| NGAAP | − | −2.251 (−4.592)** | −3.054 (−7.845)*** | −2.884 (−10.686)*** |

| IFRS | + | 3.470 (2.388) | 3.747 (4.606)** | 1.613 (1.442) |

| LAW | + | 2.599 (6.205)** | 3.043 (7.729)*** | 1.858 (2.386) |

| AID | + | 0.710 (0.739) | 0.571 (0.562) | 0.006 (0.002) |

| QUA | − | 0.184 (0.052) | 0.614 (0.632) | −0.024 (−0.001) |

| TAX | − | 0.667 (0.446) | 1.418 (2.040) | −0.267 (−0.065) |

| Control variables | ||||

| LGDP | − | 0.616 (0.775) | 0.682 (0.738) | 0.040 (0.005) |

| DEV | − | −1.979 (−2.369) | −2.106 (−3.828)** | −1.951 (−3.543)* |

| Intercept | −4.189 (−0.194) | 14.388 (1.439) | 5.770 (0.533) | |

| R2 Nagelkerke | 0.691 | 0.725 | 0.621 | |

| χ2 | 53.256*** | 65.890*** | 45.351*** | |

| Hosmer–Lemeshow | 7.376 (0.497) | 6.521 (0.589) | 3.959 (0.861) | |

| N | 73 | 84 | 74 | |

Significant at 0.01.

Notes: EDU is education level measured by total enrolments at university. NGAAP is 1 if the country has its own national set of financial accounting standards, 0 otherwise. IFRS is 1 if the country requires or permits the use of IFRS for listed companies, 0 otherwise. LAW is 1 if the country has a common law legal system, 0 otherwise. AID is foreign aid as a percentage of gross domestic product. QUA is the quality of auditing standards and accounting standards. TAX is 1 if taxable income is computed based on accounting income, 0 otherwise. LGDP is the log of gross domestic product. DEV is 1 if the country is developed, 0 otherwise.

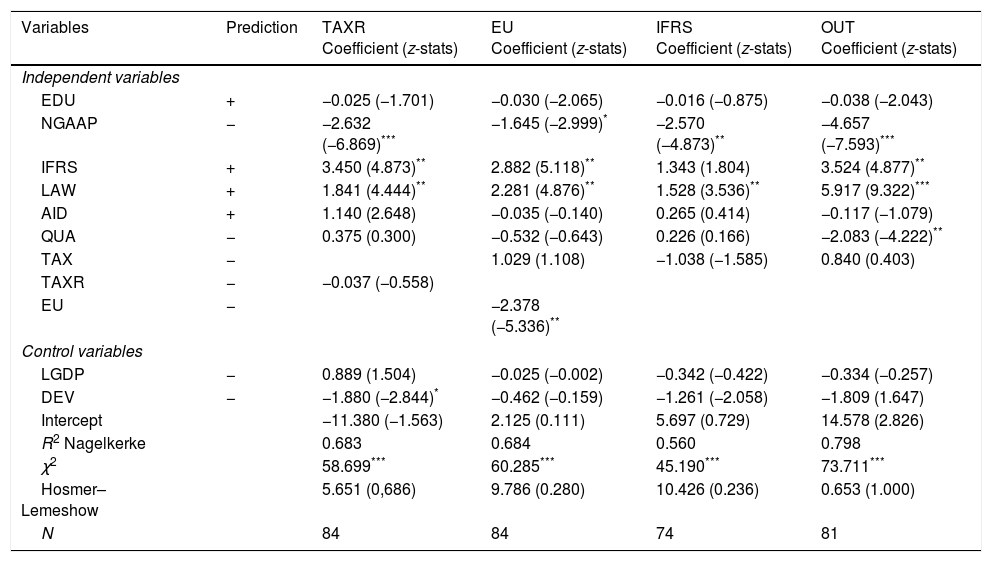

The relationship between accounting and taxation could be measured as the percentage of tax revenue in gross domestic product (TAXR). Countries where tax revenue is higher are supposed to have more control of managing their resources and more stable financial environments, which implies less likelihood of adopting IFRS for SMEs (Kaya & Koch, 2015). The result is the same (not statistically significant at 10%) as the main model, as can be seen in Table 7 (column TAXR), and so it is not possible to conclude there is an influence on the country's decision to adopt IFRS for SMEs.

Logit regression results of adoption of IFRS for SMEs – additional analysis.

| Variables | Prediction | TAXR Coefficient (z-stats) | EU Coefficient (z-stats) | IFRS Coefficient (z-stats) | OUT Coefficient (z-stats) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | |||||

| EDU | + | −0.025 (−1.701) | −0.030 (−2.065) | −0.016 (−0.875) | −0.038 (−2.043) |

| NGAAP | − | −2.632 (−6.869)*** | −1.645 (−2.999)* | −2.570 (−4.873)** | −4.657 (−7.593)*** |

| IFRS | + | 3.450 (4.873)** | 2.882 (5.118)** | 1.343 (1.804) | 3.524 (4.877)** |

| LAW | + | 1.841 (4.444)** | 2.281 (4.876)** | 1.528 (3.536)** | 5.917 (9.322)*** |

| AID | + | 1.140 (2.648) | −0.035 (−0.140) | 0.265 (0.414) | −0.117 (−1.079) |

| QUA | − | 0.375 (0.300) | −0.532 (−0.643) | 0.226 (0.166) | −2.083 (−4.222)** |

| TAX | − | 1.029 (1.108) | −1.038 (−1.585) | 0.840 (0.403) | |

| TAXR | − | −0.037 (−0.558) | |||

| EU | − | −2.378 (−5.336)** | |||

| Control variables | |||||

| LGDP | − | 0.889 (1.504) | −0.025 (−0.002) | −0.342 (−0.422) | −0.334 (−0.257) |

| DEV | − | −1.880 (−2.844)* | −0.462 (−0.159) | −1.261 (−2.058) | −1.809 (1.647) |

| Intercept | −11.380 (−1.563) | 2.125 (0.111) | 5.697 (0.729) | 14.578 (2.826) | |

| R2 Nagelkerke | 0.683 | 0.684 | 0.560 | 0.798 | |

| χ2 | 58.699*** | 60.285*** | 45.190*** | 73.711*** | |

| Hosmer–Lemeshow | 5.651 (0,686) | 9.786 (0.280) | 10.426 (0.236) | 0.653 (1.000) | |

| N | 84 | 84 | 74 | 81 | |

Significant at 0.01.

Notes: EDU is the education level. NGAAP is 1 if the country has its own national set of financial accounting standards, 0 otherwise. IFRS is 1 if the country requires or permits the use of IFRS for listed companies, 0 otherwise. LAW is 1 if the country has a common law legal system, 0 otherwise. AID is foreign aid as a percentage of gross domestic product. QUA is the quality of auditing standards and accounting standards. TAX is 1 if taxable income is computed based on accounting income, 0 otherwise. TAXR is the percentage of tax revenue in gross domestic product. LGDP is the log of gross domestic product. EU is 1 if the country is a member of the EU or 0 otherwise. DEV is 1 if the country is developed, 0 otherwise.

The European Commission has decided not to adopt IFRS for SMEs, mainly because of incompatibility between the accounting directive and IFRS for SMEs, but it can be adopted voluntarily. Running the regression with a new variable with the value of 1 if the country is a member of the EU or 0 otherwise (EU), the coefficient of this new variable is negative and statistically significant, meaning that EU countries are less likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs (column EU of Table 7).

Including the countries that are considering the adoption of IFRS for SMEs as adopters in the sample (IFRS), the results are very similar (column IFRS of Table 7) to the main model (Table 5).

Lastly, if we eliminate outlier observations (removing Switzerland, Mongolia and Oman from the sample) the results are very similar (column OUT of Table 7), except for the variable of the quality of national financial accounting standards, which ends up being statistically significant, leading us to conclude that in the case of a lower quality of national financial accounting standards adoption of IFRS for SMEs is more likely.

ConclusionsPrevious studies found a relationship between institutional factors and full IFRS adoption (Archambault & Archambault, 2009; Clements, Neill, & Stovall, 2010; Hope, Jin, & Kang, 2006; Lasmin, 2011; Ramanna & Sletten, 2014; Ritsumeikan, 2011; Shima & Yang, 2012; Zeghal & Mhedhbi, 2006; Zehri & Chouaibi, 2013), but there is a lack of studies on the adoption of IFRS for SMEs. It is very important to study SMEs considering that they represent more than 95 percent of companies worldwide and make a great contribution to job creation, technological innovation and economic output. Using a sample of 84 countries and a logit regression, we analyze the influence of institutional factors on countries’ decision to adopt IFRS for SMEs, for both developed and developing countries. The results show that countries without a national set of financial accounting standards, that permit or require the use of full IFRS for listed companies and have a common law legal system, are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs. An explanation for this could be that adopting IFRS for SMEs reduces the costs of developing their own financial accounting standards. Being familiar with, and experienced in, the IFRS environment implies a reduction in transaction costs as well being better prepared to deal with its complexity. Being part of a certain group of countries partially explains adoption of IFRS for SMEs. However, regarding education level, foreign aid, quality of the national financial accounting standards and the relationship between accounting standards and tax rules, there is no evidence of those factors influencing the country level decision to adopt IFRS for SMEs. However, if education level is measured by the literacy rate and the percentage of primary school enrolment, we conclude that countries with a lower education level are more likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs, which could be explained by the lack of qualified accountants able to develop a set of financial accounting standards in the country. The quality of national financial accounting standards and the relationship between accounting and tax are important factors but for full IFRS adoption and not for adopting IFRS for SMEs. No relationship between foreign aid and adoption of IFRS for SMEs is simply confirmation of the mixed results found for full IFRS adoption. Performing more tests we conclude that EU members are less likely to adopt IFRS for SMEs, because the EU has not adopted the standards and there are inconsistencies between the accounting directive and IFRS for SMEs. The results show that IFRS for SMEs is mainly used in developing countries and there are more countries that permit its use instead of obliging SMEs to use it.

These findings may be of interest to accounting research as well to IASB, by giving empirical evidence of the main institutional factors that could be related to adopting IFRS for SMEs. Moreover, we conclude that even considering that the IASB financial accounting standards are an example of the best accounting practices, not all countries have adopted IFRS for SMEs, which may confirm that institutional factors are one reason for not doing so (Nobes, 1998; Gray & Radebaugh, 2002).

The main limitations of this study lie in the sample selection, as this is dependent on the availability of data for every variable and the lack of detail in country profiles in the IASB. Another limitation is that the adoption of IFRS for SMEs is not the same as adopting the best accounting practices and the number of countries adopting IFRS for SMEs is constantly changing. Another way to study the relationship between institutional factors and adoption of IFRS for SMEs would be through case studies.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interests.

This variable assumes the value of 0 even if IFRS is permitted in the following cases: (a) IFRS are not much used (Japan and Madagascar); (b) IFRS are restricted to a few companies that comply with several requirements (Japan); (c) IFRS are not formally adopted (Madagascar); (d) IFRS are just used by the financial industry (Saud Arabia).