To compare the inter-practice variability in lipid metabolism laboratory tests requested by General Practitioners in Spain using appropriateness indicators and investigate the variability according to the different characteristics of the geographical regions.

Materials and methods141 clinical laboratories were invited to participate from diverse regions across Spain. We obtained the number of serum cholesterol, high-density cholesterol (HDL-cholesterol) and triglycerides requested by General Practitioners for the year 2012. Two types of appropriateness indicators were calculated: test requests per 1000 inhabitants and ratio of related tests requests (HDL-cholesterol/cholesterol, triglycerides /cholesterol). The indicators results obtained in different setting, with different type of management and in different geographical areas were compared.

ResultsWe obtained production statistics from 76 laboratories who attended a population of 17,679,195 inhabitants from 13 Communities throughout Spain. 5,823,053 cholesterol, 4,544,663 HDL-cholesterol and 5,599,358 triglycerides tests were ordered. Cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides per 1000 inhabitants indicators results ranged from 106.3 to 550.7; 20.4 to 417.5 and from 94.0 to 439.2 respectively. HDL-cholesterol/cholesterol, triglycerides/cholesterol indicators results ranged from 0.19 to 1.00 and from 0.54 to 1.00 respectively. Cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides were higher requested in rural areas. No significant differences in tests requests were observed based on Spanish Community.

ConclusionThere was a high variability in cholesterol, triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol requesting in primary care in Spain. Cholesterol was probably inappropriately under requested to screen for hypercholesterolemia in certain areas that would suggests a potential risk for inappropriate dyslipidemia screening in general population, emphasizing the need to establish interventions.

Estudiar la solicitud de pruebas de laboratorio relacionadas con el metabolismo lipídico desde atención primaria para averiguar la variabilidad en su demanda y su relación con las diferentes características de las áreas.

Material y métodosSe invitó a participar a 141 laboratorios de distintas regiones. Se requería que remitieran el número de pruebas de colesterol, colesterol HDL (cHDL) y triglicéridos solicitadas desde atención primaria en el año 2012. Se calculó la solicitud anual por 1.000 habitantes y el ratio de solicitud de 2 pruebas relacionadas.

ResultadosSe recibió la estadística de 76 laboratorios que atendían a una población de 17.679.195 habitantes y pertenecían a 13 comunidades españolas. En total, se solicitaron 5.823.053 pruebas de colesterol, 4.544.663 de cHDL y 5.599.358 de triglicéridos. El número de pruebas de colesterol, cHDL y triglicéridos solicitados por 1.000 habitantes fue de 106,3 a 550,7, de 20,4 a 417,5 y de 94,0 a 439,2, respectivamente. El ratio de solicitudes de cHDL/colesterol y triglicéridos/colesterol fue de 0,19 a 1,00 y de 0,54 a 1,00, respectivamente. El colesterol, el cHDL y los triglicéridos fueron más solicitados en áreas rurales que en urbanas o rurales/urbanas. No se observaron diferencias relacionadas con la comunidad autónoma.

ConclusiónExistió una gran variabilidad en la solicitud desde atención primaria de colesterol, cHDL y triglicéridos El colesterol en determinadas áreas es probable que fuera inadecuadamente solicitado por defecto, lo que sugiere un potencial riesgo de inadecuado cribado de dislipidemia en la población general e indica la necesidad de diseñar y establecer medidas correctoras.

Currently, at least 15% of the general population with diabetes, hypertension, or dyslipidemia are undiagnosed.1 However, the increase of the prevalence of dyslipidemia as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease emphasizes the need for a proper screening. This is done through the measurement of serum cholesterol, triglycerides and high-density cholesterol (HDL-cholesterol) levels in fasting samples.2 Thereafter, abnormal screening results should be confirmed by a repeated sample on another occasion, and the average of both results should be used for risk assessment.3

An active search for patients with hypercholesterolemia is adviced, through cholesterol measurement in the general population before age 35 in men and 45 in women. Then every 5 years up to 75 years. Above that age cholesterol should be measured once, if not performed before. Hypertriglyceridemia detection is recommended only in certain cases. However, primary screening for the detection of hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia at any age is required if the patient is diabetic, or there is family history of premature cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, or other risk factors.3,4 Regarding HDL-cholesterol, its measurement is also recommended in cases of hypercholesterolemia. As a general rule, an increase of 1mg/dL in is associated with a 3% lower risk of coronary heart disease in women, and a 2% in men.5

Nowadays, the detection of lipid disorders in adults lies in primary care setting. Previous studies showed the existence of inequalities in preventive practice among practitioners.6,7 A research in a country with two scenarios of primary care showed that general practitioners (GPs) requested more cholesterol and triglycerides than family medicine doctors and referred that from an economic perspective this difference was not justified.8 Other authors stated a high variability in the number of HDL-cholesterol requested between general practices expressed per 1000 practice patients a year, and also when expressed as a percentage of the requests for cholesterol.9 These facts emphasize the need for interventions to reduce the large differences in the tests requested by GPs. A first step will be to investigate the actual behaviour and variability, trying to identify the root causes of this variability, if it exists, and hence of inappropriateness, if discovered.

The aim of this research was, to study the inter-practice variability in lipid laboratory tests requested by GPs and to compare and analyze the variability according to the different characteristics of the geographical regions.

Methods and materialsData collectionEncouraged by the previous pilot studies in the Valencian Community10 and all around Spain11,12 a call for data was posted via email. 141 laboratories Spanish were invited to participate, to fill out an enrollment form and submit their results online. We obtained production statistics (number of tests requested by GPs) for the year 2012 from laboratories at different hospitals from diverse regions across Spain. Every patient seen in any primary care center of any of these health departments, regardless of the reason for consultation, gender or age, was included in the study. Each participating laboratory was required to be able to obtain patient data from local databases and to provide organizational data (i.e. population served,, location). Cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides tests requesting were examined in a cross-sectional study.

Data processingAfter collecting the data, two types of appropriateness indicators were calculated the number of each investigated test (cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol or triglycerides) per 1000 inhabitants and ratios of related tests requests (HDL-cholesterol/cholesterol, triglycerides/cholesterol). In order to explore the inter-practice variability, another indicator, the “index of variability”, was calculated as follows: top decile divided by bottom decile (90th percentile/10th percentile).

We calculated if the rate of test requests was different according to the setting (rural, urban, or rural-urban) of the hospital.

Finally, the indicator results obtained in the laboratories in the three regions with the higher number of departments participating in the study were compared between them and to the pooled results of the remaining regions in order to establish whether there were regional differences in the requesting patterns.

Statistical methodsThe statistical treatment of the calculated data included: the distribution, the mean, 95% confidence level for the mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile range. The analysis of the distribution of the number of test requests per 1,000 inhabitants was conducted by way of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

The differences in the indicators results according to the hospital characteristics and per region were calculated by way of the Kruskal-Wallis test analysis.

A two-sided p ≤ 0.05 rule was utilized as the criterion for rejecting the null hypothesis of no difference.

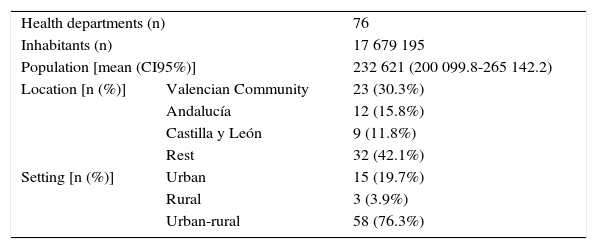

ResultsWe obtained production statistics from 76 laboratories at different hospitals from diverse regions across Spain (Valencian Community, 23 laboratories and 4,848,900 patients; Andalucía, 12 laboratories and 3,849,485 patients; Castilla y León, 9 laboratories and 1,695,916 patients, and remaining regions 32 laboratories, 7,284,894 patients). 17,679,195 patients were included in the study, from 13 Communities throughout Spain. 5,823,053 cholesterol, 4,544,663 HDL-cholesterol and 5,599,358 triglycerides tests were ordered. Table 1 displays a summary of the organizational data of the different laboratories that participated in the study.

Descriptive characteristics of the hospitals/health care departments that participated in the study.

| Health departments (n) | 76 | |

| Inhabitants (n) | 17 679 195 | |

| Population [mean (CI95%)] | 232 621 (200 099.8-265 142.2) | |

| Location [n (%)] | Valencian Community | 23 (30.3%) |

| Andalucía | 12 (15.8%) | |

| Castilla y León | 9 (11.8%) | |

| Rest | 32 (42.1%) | |

| Setting [n (%)] | Urban | 15 (19.7%) |

| Rural | 3 (3.9%) | |

| Urban-rural | 58 (76.3%) | |

CI: Confidence interval of the mean.

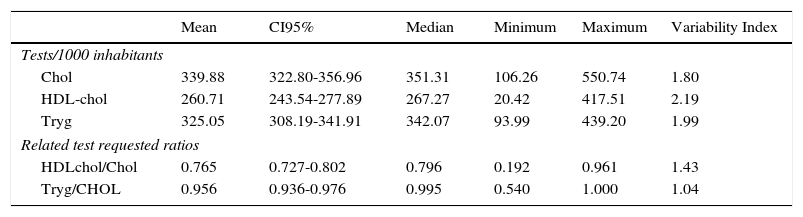

The descriptive statistical analysis and the variability index for the number of requests per 1000 inhabitants and ratios of related tests, is shown in Table 2. The variability of ratios of related tests was also very significant.

Descriptive statistical analysis and the variability index for the number of requests per 1000 inhabitants and ratios of related tests.

| Mean | CI95% | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Variability Index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tests/1000 inhabitants | ||||||

| Chol | 339.88 | 322.80-356.96 | 351.31 | 106.26 | 550.74 | 1.80 |

| HDL-chol | 260.71 | 243.54-277.89 | 267.27 | 20.42 | 417.51 | 2.19 |

| Tryg | 325.05 | 308.19-341.91 | 342.07 | 93.99 | 439.20 | 1.99 |

| Related test requested ratios | ||||||

| HDLchol/Chol | 0.765 | 0.727-0.802 | 0.796 | 0.192 | 0.961 | 1.43 |

| Tryg/CHOL | 0.956 | 0.936-0.976 | 0.995 | 0.540 | 1.000 | 1.04 |

Test: cholesterol (Chol); HDL-cholesterol (HDL-c); triglycerides (Tg).

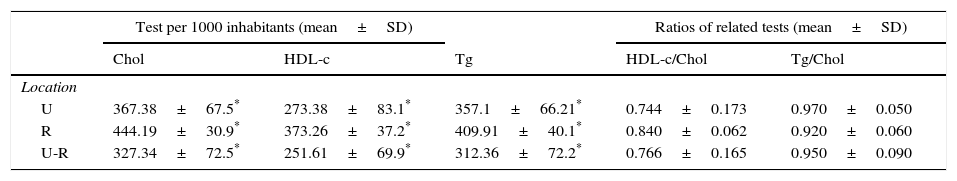

In rural hospitals, cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides tests per 1000 inhabitant's indicators results were higher than in urban or rural-urban locations. However, no significant differences in ratio of related tests requests were detected (Table 3).

Differences of appropriateness indicators results obtained at the laboratories of the different locations and regarding the type of management.

| Test per 1000 inhabitants (mean±SD) | Ratios of related tests (mean±SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chol | HDL-c | Tg | HDL-c/Chol | Tg/Chol | |

| Location | |||||

| U | 367.38±67.5* | 273.38±83.1* | 357.1±66.21* | 0.744±0.173 | 0.970±0.050 |

| R | 444.19±30.9* | 373.26±37.2* | 409.91±40.1* | 0.840±0.062 | 0.920±0.060 |

| U-R | 327.34±72.5* | 251.61±69.9* | 312.36±72.2* | 0.766±0.165 | 0.950±0.090 |

Loc.: Location; U: Urban; R: Rural; U-R: Urban-Rural.

Test: cholesterol (Chol); HDL-cholesterol (HDL-c); triglycerides (Tg).

Neither there was no statistically significant difference between geographical regions in appropriateness indicators (Figures 1 and 2).

The study results highlight the variability in the request of lipid metabolism tests in Spain. The triglycerides/cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol/cholesterol ratios, even close to one in the first case, were high in all the studied laboratories, in spite of the current recommendations that do not recommend triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol measurement in the general population. The observed higher request of cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides in rural areas, inhabited by older population,13 is difficult to explain as cholesterol screening is not recommended over 75 years of age.

It is very difficult to know, in view of the obtained results, if cholesterol was appropriately requested to detect hypercholesterolemia in the general population. In the areas with the lowest requests, 106 tests per 1000 inhabitants, the test was probably not enough ordered to cover population-based cholesterol screening: every 5 years starting at 35 years in male, and 45 years in female patients. Furthermore, the high test request variability observed in our study - from 106 to 550 per 1000 inhabitants- is difficult to be exclusively explained by the population or patient case mix differences. Probably additional reasons are the root causes, as for instance different requesting habits of the GPs in the different studied areas.

Less than 10% of the population is at high risk of cardiovascular disease. However the low to intermediate risk group is so large that most cardiovascular events will occur in that group.14,15 This emphasizes the need of a proper dyslipidemia screening in general population. It is necessary to standardize the request of such laboratory tests to be sure, as a primordial need, that cholesterol is appropriate requested to screen hypercholesterolemia in the general population. An effort must be done in the less demanding areas to stimulate the cholesterol request, in view our study results that showed that cholesterol was probably under requested in certain areas.

Besides promoting the request of cholesterol in some regions, another step to achieve a correct request in the screening of lipid metabolism disorders would be to decrease the requests of triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol, as proposed earlier by some authors.8 As in a prior study in the United Kingdom,8 our data also suggested that HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides were probably over requested in many areas in Spain. More studies are needed to investigate the specific triglycerides/cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol/cholesterol indicators targets to reach in primary care setting in order to establish strategies for a proper lipid tests requesting.

The study had certain limitations. The differences in lipid tests request between health care regions in Spain could be partly explained by the possible variability in the patient population, or more or less often visit their specialist instead of the GP depending on the area.

There was a high variability in cholesterol, triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol requesting in primary care in Spain. Cholesterol was probably inappropriately under requested to screen for hypercholesterolemia in certain areas that would suggests a potential risk for inappropriate dyslipidemia screening in general population. However triglycerides request, at a one to one ratio when compared to cholesterol in most areas, seemed to be inappropriately over requested. Those results emphasize the need to establish interventions to achieve an appropriate and homogenized lipid tests request. More studies are needed to establish indicators targets for a correct and maintained evaluation of appropriate lipid tests request.

Funding StatementThis research received specific grant (Ignacio H. de Larramendi Aid to research) from Fundación Mapfre.

Competing InterestNone declared.

Members of the REDCONLAB working group are the following (in alphabetical order): Alfonso Pérez-Martínez (Hospital Morales Meseguer); Amparo Miralles (Hospital de Sagunto); Ana Santo-Quiles (Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Elda); Ángela Rodriguez-Piñero (Hospital Universitario de Mostotes); Angeles Giménez-Marín (Hospital de Antequera); Antonio Buño-Soto (Hospital La Paz, Madrid); Antonio Gómez del Campo (Complejo Asistencial de Ávila); Antonio León-Juste (Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva); Antonio Moro-Ortiz (Hospital de Valme, Sevilla); Begoña Laiz (Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe de Valencia); Berta González-Ponce (Hospital Da Costa, Burela); Carmen Hernando de Larramendi (Hospital Severo Ochoa de Leganés); Carmen Vinuesa (Hospital de Vinaros); Cesáreo García-García (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca); Concepción Magadán-Núñez (Hospital Arquitecto Marcide, El Ferrol); Consuelo Tormo (Hospital General Universitario de Elche); Cristina Santos-Rosa (Hospital Río Tinto, Huelva); Cristóbal Avivar (Hospital de Poniente, El Ejido); Diego Benítez Benítez (Hospital de Orihuela); Eduardo Sanchez-Fernandez (Hospital del Vinalopo, Elche); Emilia Moreno-Noguero (Hospital Can Misses); Enrique Rodríguez-Borja (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia); Esther Roldán-Fontana (Hospital La Merced. Area de Gestión Sanitaria Sevilla Este); Fco. Javier Martín Oncina (Hospital Virgen del Puerto de Plasencia, Caceres); Félix Gascón (Hospital Valle de los Pedroches, Pozoblanco); Fernando Rodríguez Cantalejo (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofia de Cordoba); Fidel Velasco Pena (Hospital Virgen de Altagracia, Manzanares); Francisco Miralles (Hospital Lluis Alcanyis, Xativa); Goitzane Marcaida (Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia); Marta Barrionuevo (Hospital Universitario Principe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares); Inmaculada Domínguez-Pascual (Hospital General Universitario Virgen del Rocio, Sevilla); Isidoro Herrera Contreras (Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén); Jose Antonio Ferrero (Hospital General de Castellón); Jose Luis Barberà (Hospital de Manises); Jose Luis Quilez Fernandez (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofia de Murcia); Jose Luis Ribes-Vallés (Hospital de Manacor); María Fernández García.

(Hospital Santiago Apostol de Miranda de Ebro); Jose Sastre (Hospital Virgen de los Lirios, Alcoy); Jose Vicente Garcia-Lario (Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada); Juan Ignacio Molinos (Hospital Sierrallana, Torrelavega); Juan Molina (Hospital Comarcal de La Marina, Villajoyosa); Juan Ramón Martínez-Inglés (Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía, Cartagena); Julian Diaz (Hospital Francesc de Borja, Gandia); Laura Navarro Casado (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete); Leopoldo Martín-Martín (Hospital General de La Palma); Lola Máiz Suárez (Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti, HULA, Lugo); Luís Rabadán (Complejo Asistencial de Soria); M Dolores Calvo (Hospital Clinico de Valladolid); M. Amalia Andrade-Olivie (Hospital Xeral-Cies, CHU Vigo); M. Angeles Rodríguez-Rodriguez (Complejo Asistencial de Palencia); M. Carmen Gallego Ramirez (Hospital Rafael Mendez, Lorca); M. Mercedes Herranz-Puebla (Hospital Universitario de Getafe); M. Victoria Poncela-Garcia (Hospital Universitario de Burgos); Mª José Baz (Hospital de Llerena, Badajoz); Mª José Martínez-Llopis (Hospital de Denia); Mª.Teresa Avello-López (Hospital San Agustín, Avilés); Mabel Llovet (Hospital Verge de la Cinta, Tortosa); Mamen Lorenzo (Hospital de Puertollano); Marcos Lopez-Hoyos (Hospital Universitario Marques de Valdecilla); Maria Jose Zaro (Hospital Don Benito-Villanueva); Maria Luisa Lopez-Yepes (Hospital Virgen del Castillo de Yecla); Mario Ortuño (Hospital Universitario La Ribera); Marisa Graells (Hospital General Universitario de Alicante); Marta García-Collía (Hospital Ramon y Cajal, Madrid); Martin Yago (Hospital de Requena); Mercedes Muros (Hospital Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria, Tenerife); Nuria Estañ (Hospital Dr. Peset, Valencia); Nuria Fernández-García (Hospital Universitario Rio Hortega, Valladolid); Pilar Garcia-Chico Sepulveda (Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real); Ricardo Franquelo (Hospital Virgen de la Luz de Cuenca); Ruth Gonzalez Tamayo (Hospital de Torrevieja); Silvia Pesudo (Hospital La Plana); Vicente Granizo-Dominguez (Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara); Vicente Villamandos-Nicás (Hospital Santos Reyes, Aranda del Duero); Vidal Perez –Valero (Hospital Regional de Málaga).