Preoperative anemia affects approximately one third of surgical patients. It increases the risk of blood transfusion and influences short- and medium-term functional outcomes, increases comorbidities, complications and costs. The “Patient Blood Management” (PBM) programs, for integrated and multidisciplinary management of patients, are considered as paradigms of quality care and have as one of the fundamental objectives to correct perioperative anemia. PBM has been incorporated into the schemes for intensified recovery of surgical patients: the recent Enhanced Recovery After Surgery 2021 pathway (in Spanish RICA 2021) includes almost 30 indirect recommendations for PBM.

ObjectiveTo make a consensus document with RAND/UCLA Delphi methodology to increase the penetration and priority of the RICA 2021 recommendations on PBM in daily clinical practice.

Material and MethodsA coordinating group composed of 6 specialists from Hematology-Hemotherapy, Anesthesiology and Internal Medicine with expertise in anemia and PBM was formed. A survey was elaborated using Delphi RAND/UCLA methodology to reach a consensus on the key areas and priority professional actions to be developed at the present time to improve the management of perioperative anemia. The survey questions were extracted from the PBM recommendations contained in the RICA 2021 pathway. The development of the electronic survey (Google Platform) and the management of the responses was the responsibility of an expert in quality of care and clinical safety.

Participants were selected by invitation from speakers at AWGE-GIEMSA scientific meetings and national representatives of PBM-related working groups (Seville Document, SEDAR HTF section and RICA 2021 pathway participants).

In the first round of the survey, the anonymized online questionnaire had 28 questions: 20 of them were about PBM concepts included in ERAS guidelines (2 about general PBM organization, 10 on diagnosis and treatment of preoperative anemia, 3 on management of postoperative anemia, 5 on transfusion criteria) and 8 on pending aspects of research. Responses were organized according to a 10-point Likter scale (0: strongly disagree to 10: strongly agree). Any additional contributions that the participants considered appropriate were allowed. They were considered consensual because all the questions obtained an average score of more than 9 points, except one (question 14).

The second round of the survey consisted of 37 questions, resulting from the reformulation of the questions of the first round and the incorporation of the participants' comments. It consisted of 2 questions about general organization of PBM programme, 15 questions on the diagnosis and treatment of preoperative anemia; 3 on the management of postoperative anemia, 6 on transfusional criteria and finally 11 questions on aspects pending od future investigations.

Statistical treatment: tabulation of mean, median and interquartiles 25–75 of the value of each survey question (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

ResultsExcept for one, all the recommendations were accepted. Except for three, all above 8, and most with an average score of 9 or higher. They are grouped into:

1.- “It is important and necessary to detect and etiologically diagnose any preoperative anemia state in ALL patients who are candidates for surgical procedures with potential bleeding risk, including pregnant patients”.

2.- “The preoperative treatment of anemia should be initiated sufficiently in advance and with all the necessary hematinic contributions to correct this condition”.

3.- “There is NO justification for transfusing any unit of packed red blood cells preoperatively in stable patients with moderate anemia Hb 8−10g/dL who are candidates for potentially bleeding surgery that cannot be delayed.”

4.- “It is recommended to universalize restrictive criteria for red blood cell transfusion in surgical and obstetric patients.”

5.- “Postoperative anemia should be treated to improve postoperative results and accelerate postoperative recovery in the short and medium term”.

ConclusionsThere was a large consensus, with maximum acceptance,strong level of evidence and high recommendation in most of the questions asked. Our work helps to identify initiatives and performances who can be suitables for the implementation of PBM programs at each hospital and for all patients.

La anemia preoperatoria afecta a aproximadamente a un tercio de los pacientes quirúrgicos. Incrementa el riesgo de transfusión sanguínea e influye sobre los resultados funcionales a corto y medio plazo, incrementa comorbilidades, complicaciones y costes. Los programas de «Gestión de Sangre del Paciente» (GSP), de manejo integral y multidisciplinar de los pacientes, se consideran como paradigmas de calidad asistencial y tienen como uno de los objetivos fundamentales corregir la anemia perioperatoria. La GSP ha sido incorporada en los esquemas de recuperación intensificada de los pacientes quirúrgicos: en la reciente vía de Recuperación Intensificada en Cirugía del Adulto- RICA 2021- se recogen casi 30 recomendaciones indirectas de GSP.

ObjetivoRealizar un documento de consenso con metodología Delphi RAND/UCLA para incrementar la penetración y prioridad de las recomendaciones de la vía RICA 2021 sobre GSP en la práctica clínica cotidiana.

Material y métodosSe constituyó un grupo coordinador compuesto por 6 especialistas de Hematología-Hemoterapia, Anestesiología y Medicina Interna expertos en anemia y GSP.

Se elaboró una encuesta con metodología Delphi RAND/UCLA para consensuar las áreas clave y las acciones profesionales prioritarias a desarrollar en el momento actual para mejorar el manejo de la anemia perioperatoria. Las preguntas de la encuesta se extrajeron de las recomendaciones GSP contenidas en la vía RICA 2021. La elaboración de la encuesta electrónica (Google Platform) y la gestión de las respuestas fue responsabilidad de un experto en calidad asistencial y seguridad clínica.

Los participantes fueron seleccionados por invitación entre ponentes de reuniones científicas de AWGE-GIEMSA y representantes nacionales de grupos de trabajo relacionados con la GSP (Documento de Sevilla, sección HTF de SEDAR y participantes de la vía RICA 2021).

En la primera ronda de la encuesta, tal como se expone en las Tablas 1, 2 y 3, el cuestionario online anonimizado tenía 28 preguntas: 20 de ellas referidas a las recomendaciones en GSP contenidos en la vía RICA (sobre aspectos generales 2, sobre diagnóstico y tratamiento de la anemia preoperatoria 10, sobre manejo de la anemia postoperatoria 3 y 5 sobre criterios transfusionales) y 8 sobre aspectos pendientes de investigación. Se organizaron las respuestas según escala de Likter de 10 puntos (0: totalmente en desacuerdo hasta 10: completamente de acuerdo). Se permitieron las aportaciones suplementarias que los participantes consideraron oportunos incorporar. Se consideraron consensuadas, porque todas las preguntas obtuvieron una puntuación superior a 9 puntos de promedio, excepto una (pregunta 14).

La segunda ronda de la encuesta estuvo formada por 37 preguntas, resultantes de la reformulación de las preguntas de la primera ronda y de la incorporación de los comentarios de los participantes. Estuvo constituida por 2 preguntas sobre aspectos generales de GSP, 15 preguntas sobre diagnóstico y tratamiento de la anemia preoperatoria; 3 sobre el manejo de la anemia postoperatoria y 6 sobre criterios transfusionales perioperatorios, además de 11 sobre aspectos pendientes de investigación, (Tablas 1, 2 y 3 del manuscrito).

Tratamiento estadístico: tabulación de la media, mediana e intercuartiles 25–75 de los valores de cada pregunta de la encuesta.

ResultadosA excepción de una, todas las recomendaciones fueron aceptadas. Salvo tres, todas con puntuación por encima de 8, y la mayoría con una puntuación promedio de 9 o superior. Se agrupan en:

1.- «Es importante y necesaria la detección y el diagnóstico etiológico de cualquier estado de anemia preoperatoria en TODOS los pacientes candidatos a procedimientos quirúrgicos con riesgo potencial de sangrado, incluidas las pacientes gestantes».

2.- «El tratamiento preoperatorio de una anemia debe iniciarse con antelación suficiente y con todos los aportes hematínicos necesarios para corregir dicho estado».

3.- «NO tiene ninguna justificación transfundir ninguna unidad de concentrado de hematíes preoperatoria en pacientes estables, con anemia moderada Hb 8−10g/dL candidatos a cirugía potencialmente sangrante que no pueda ser demorada».

4.- «Se recomienda universalizar criterios restrictivos en la transfusión de hematíes en pacientes quirúrgicos y obstétricas».

5.- «Debe tratarse la anemia postoperatoria para mejorar los resultados postoperatorios y acelerar la recuperación postoperatoria a corto y medio plazo».

ConclusionesHubo un gran consenso, con la máxima aceptación, nivel de evidencia fuerte y recomendación alta en la mayoría de las preguntas realizadas. El presente documento contribuye a identificar iniciativas y actuaciones potencialmente implantables en todos los centros hospitalarios y para todos los pacientes, basadas en la mejor evidencia científica disponible en el momento actual.

Preoperative anaemia affects approximately one third of surgical patients, and is particularly prevalent in patients undergoing gastrointestinal cancer surgery, vascular and cardiac surgery, and obstetric surgery.1 Preoperative anaemia increases the risk of perioperative blood transfusion and influences surgical outcomes in the short and medium term by decompensating comorbidities, prolonging hospital stays, and delaying postoperative functional recovery.2,3

Therefore, optimising preoperative haemoglobin (Hb) levels in surgical patients protects against moderate and severe complications in the 30-day postoperative period.4

The main objectives of the Patient Blood Management (PBM) program, which is currently considered a paradigm of care quality, are to correct preoperative anaemia and implement efficient perioperative transfusion criteria that can reduce the considerable, alarming variability in current transfusion practices.5,6

In recent years there have been calls to coordinate PBM with another highly regarded program - Spain’s RICA (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery) pathway.7,8 As a result, the recent RICA 2021 pathway contains more than 20 specific and almost 10 indirect PBM recommendations.9

However, despite the accumulated evidence and recommendations supporting the study and treatment of preoperative anaemia, the use of tranexamic acid, and the application of restrictive transfusion criteria, implementation of these strategies remains low.10

In this document, we present the results of a Delphi RAND/UCLA study intended to prioritize RICA 2021 recommendations on PBM and identify specific, basic strategies that will increase implementation of these recommendations in routine clinical practice.

Material and methodWe first created a task force consisting of 6 specialists in Haematology-Haemotherapy, Anaesthesiology, and Internal Medicine with several years’ experience in PBM.

The task force decided to perform a Delphi RAND/UCLA survey in order to obtain consensus on the key areas and priority activities currently needed to improve perioperative management of anaemia and blood transfusion.

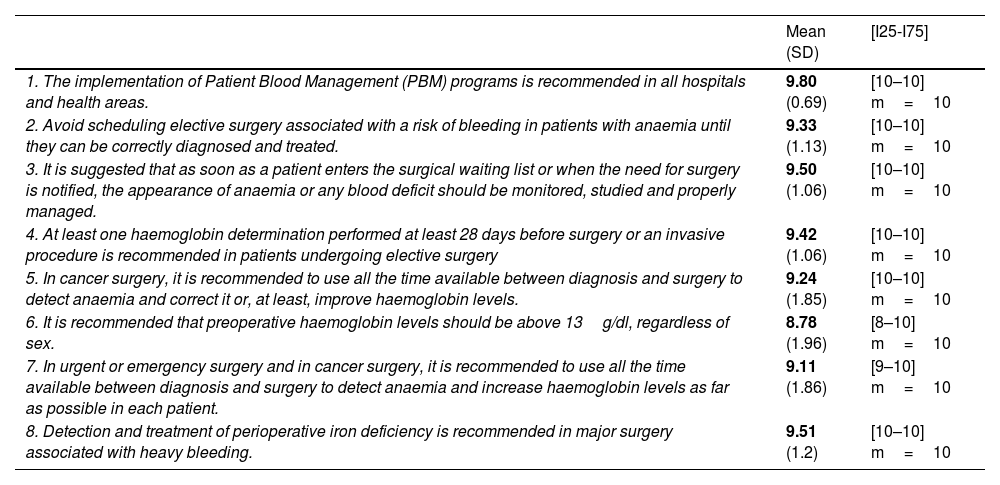

To draw up the Delphi questionnaire, the members of the task force selected a series of PBM recommendations included in the ERAS 2021 pathway (Table 1).

PBM recommendations included in the 2021 RICA pathway and degree of expert consensus.

| Mean (SD) | [I25-I75] | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. The implementation of Patient Blood Management (PBM) programs is recommended in all hospitals and health areas. | 9.80 (0.69) | [10–10] m=10 |

| 2. Avoid scheduling elective surgery associated with a risk of bleeding in patients with anaemia until they can be correctly diagnosed and treated. | 9.33 (1.13) | [10–10] m=10 |

| 3. It is suggested that as soon as a patient enters the surgical waiting list or when the need for surgery is notified, the appearance of anaemia or any blood deficit should be monitored, studied and properly managed. | 9.50 (1.06) | [10–10] m=10 |

| 4. At least one haemoglobin determination performed at least 28 days before surgery or an invasive procedure is recommended in patients undergoing elective surgery | 9.42 (1.06) | [10–10] m=10 |

| 5. In cancer surgery, it is recommended to use all the time available between diagnosis and surgery to detect anaemia and correct it or, at least, improve haemoglobin levels. | 9.24 (1.85) | [10–10] m=10 |

| 6. It is recommended that preoperative haemoglobin levels should be above 13g/dl, regardless of sex. | 8.78 (1.96) | [8–10] m=10 |

| 7. In urgent or emergency surgery and in cancer surgery, it is recommended to use all the time available between diagnosis and surgery to detect anaemia and increase haemoglobin levels as far as possible in each patient. | 9.11 (1.86) | [9–10] m=10 |

| 8. Detection and treatment of perioperative iron deficiency is recommended in major surgery associated with heavy bleeding. | 9.51 (1.2) | [10–10] m=10 |

Mean; (SD: standard deviation); [I25–I75]=[Interquartile 25–Interquartile 75]; m=median.

A haematologist with many years’ experience in care quality and clinical safety developed the online questionnaire (Google survey platform) and managed the responses.

Speakers at AWGE-GIEMSA (Anaemia Working Group España - Grupo Internacional de estudios Multidisciplinares sobre Autotransfusión) scientific meetings and national representatives of PBM-related task forces from SEDAR’s HTF (Haemostasis, Transfusion and Fluid Therapy) division and the experts involved in Haematology, Haemotherapy, and Haemostasis sections of Spain’s RicA 2021 pathway were invited to take part in the Delphi rounds. By receiving and sending the completed questionnaire, participants gave their implicit informed consent to take part in the study.

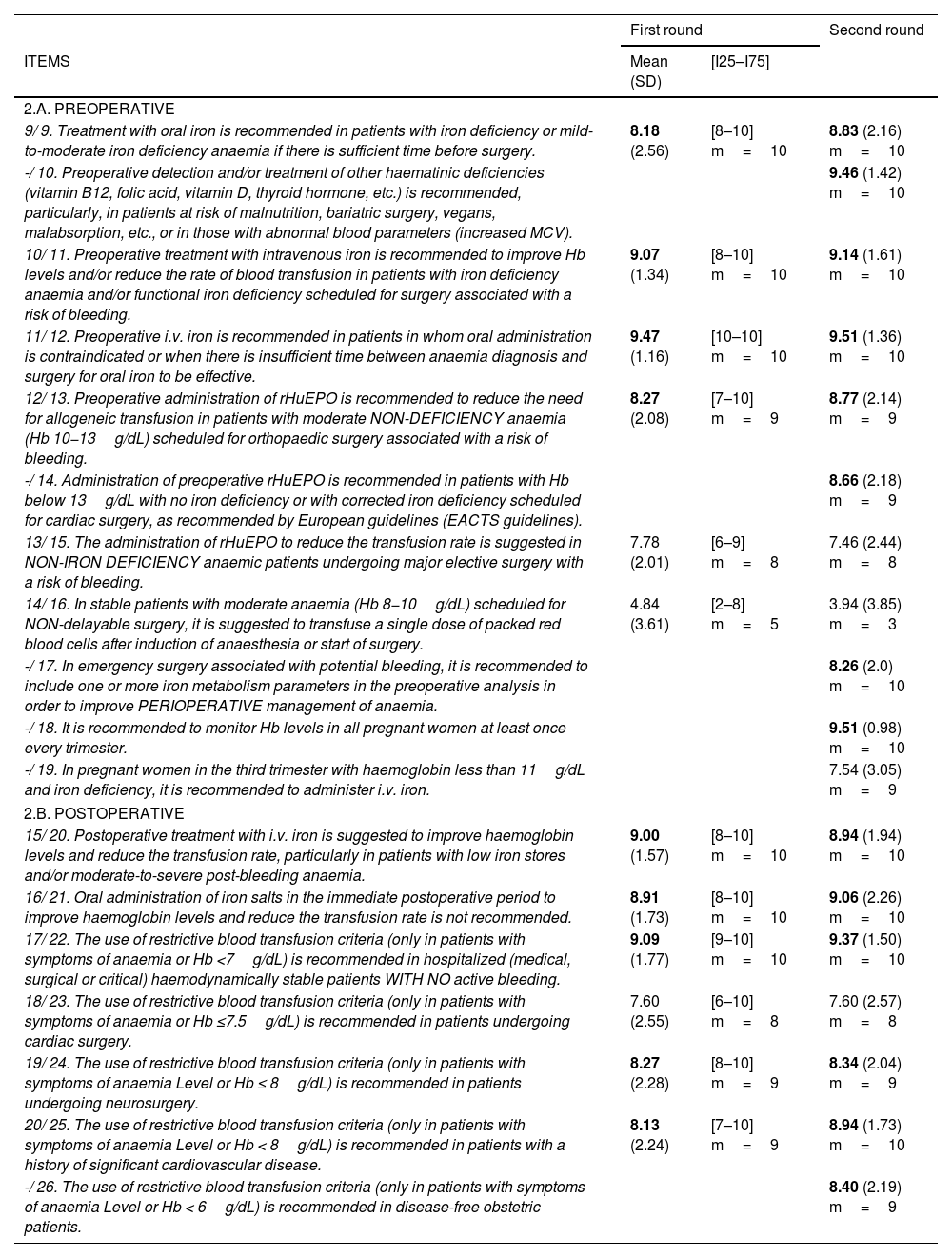

In the first Delphi round, participants received the anonymised online questionnaire consisting of a total of 28 items: 20 items on PBM recommendations included in the RICA pathway (2 on general and organizational aspects of the PBM program; 10 on diagnosis and treatment of preoperative anaemia; 3 on management of postoperative anaemia; and 5 on transfusion criteria), in addition to 8 items on future lines of research. The questions were rated on a 10-point Likert scale (from 0: completely disagree to 10: completely agree). Consensus was reached on an item when over 70% of respondents awarded it 8 or more points. Respondents were also allowed to add any comments or questions they would like to see included in the next Delphi round.

The second round consisted of 37 questions: 2 related to general aspects of the PBM program; 15 on diagnosis and treatment of preoperative anaemia; 3 on postoperative management of anaemia; 6 on perioperative transfusion criteria; and 11 on future lines of research.

For this reason, the numbering of questions shown in Tables 2 and 3 varies slightly: N1/N2: question number in the first round/question number in the second round. -/N2: question absent from the first round/question number in the second round.

Questionnaire items in the Delphi rounds.

| First round | Second round | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ITEMS | Mean (SD) | [I25–I75] | |

| 2.A. PREOPERATIVE | |||

| 9/ 9. Treatment with oral iron is recommended in patients with iron deficiency or mild-to-moderate iron deficiency anaemia if there is sufficient time before surgery. | 8.18 (2.56) | [8–10] m=10 | 8.83 (2.16) m=10 |

| -/ 10. Preoperative detection and/or treatment of other haematinic deficiencies (vitamin B12, folic acid, vitamin D, thyroid hormone, etc.) is recommended, particularly, in patients at risk of malnutrition, bariatric surgery, vegans, malabsorption, etc., or in those with abnormal blood parameters (increased MCV). | 9.46 (1.42) m=10 | ||

| 10/ 11. Preoperative treatment with intravenous iron is recommended to improve Hb levels and/or reduce the rate of blood transfusion in patients with iron deficiency anaemia and/or functional iron deficiency scheduled for surgery associated with a risk of bleeding. | 9.07 (1.34) | [8–10] m=10 | 9.14 (1.61) m=10 |

| 11/ 12. Preoperative i.v. iron is recommended in patients in whom oral administration is contraindicated or when there is insufficient time between anaemia diagnosis and surgery for oral iron to be effective. | 9.47 (1.16) | [10–10] m=10 | 9.51 (1.36) m=10 |

| 12/ 13. Preoperative administration of rHuEPO is recommended to reduce the need for allogeneic transfusion in patients with moderate NON-DEFICIENCY anaemia (Hb 10−13g/dL) scheduled for orthopaedic surgery associated with a risk of bleeding. | 8.27 (2.08) | [7–10] m=9 | 8.77 (2.14) m=9 |

| -/ 14. Administration of preoperative rHuEPO is recommended in patients with Hb below 13g/dL with no iron deficiency or with corrected iron deficiency scheduled for cardiac surgery, as recommended by European guidelines (EACTS guidelines). | 8.66 (2.18) m=9 | ||

| 13/ 15. The administration of rHuEPO to reduce the transfusion rate is suggested in NON-IRON DEFICIENCY anaemic patients undergoing major elective surgery with a risk of bleeding. | 7.78 (2.01) | [6–9] m=8 | 7.46 (2.44) m=8 |

| 14/ 16. In stable patients with moderate anaemia (Hb 8−10g/dL) scheduled for NON-delayable surgery, it is suggested to transfuse a single dose of packed red blood cells after induction of anaesthesia or start of surgery. | 4.84 (3.61) | [2–8] m=5 | 3.94 (3.85) m=3 |

| -/ 17. In emergency surgery associated with potential bleeding, it is recommended to include one or more iron metabolism parameters in the preoperative analysis in order to improve PERIOPERATIVE management of anaemia. | 8.26 (2.0) m=10 | ||

| -/ 18. It is recommended to monitor Hb levels in all pregnant women at least once every trimester. | 9.51 (0.98) m=10 | ||

| -/ 19. In pregnant women in the third trimester with haemoglobin less than 11g/dL and iron deficiency, it is recommended to administer i.v. iron. | 7.54 (3.05) m=9 | ||

| 2.B. POSTOPERATIVE | |||

| 15/ 20. Postoperative treatment with i.v. iron is suggested to improve haemoglobin levels and reduce the transfusion rate, particularly in patients with low iron stores and/or moderate-to-severe post-bleeding anaemia. | 9.00 (1.57) | [8–10] m=10 | 8.94 (1.94) m=10 |

| 16/ 21. Oral administration of iron salts in the immediate postoperative period to improve haemoglobin levels and reduce the transfusion rate is not recommended. | 8.91 (1.73) | [8–10] m=10 | 9.06 (2.26) m=10 |

| 17/ 22. The use of restrictive blood transfusion criteria (only in patients with symptoms of anaemia or Hb <7g/dL) is recommended in hospitalized (medical, surgical or critical) haemodynamically stable patients WITH NO active bleeding. | 9.09 (1.77) | [9–10] m=10 | 9.37 (1.50) m=10 |

| 18/ 23. The use of restrictive blood transfusion criteria (only in patients with symptoms of anaemia or Hb ≤7.5g/dL) is recommended in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. | 7.60 (2.55) | [6–10] m=8 | 7.60 (2.57) m=8 |

| 19/ 24. The use of restrictive blood transfusion criteria (only in patients with symptoms of anaemia Level or Hb ≤ 8g/dL) is recommended in patients undergoing neurosurgery. | 8.27 (2.28) | [8–10] m=9 | 8.34 (2.04) m=9 |

| 20/ 25. The use of restrictive blood transfusion criteria (only in patients with symptoms of anaemia Level or Hb < 8g/dL) is recommended in patients with a history of significant cardiovascular disease. | 8.13 (2.24) | [7–10] m=9 | 8.94 (1.73) m=10 |

| -/ 26. The use of restrictive blood transfusion criteria (only in patients with symptoms of anaemia Level or Hb < 6g/dL) is recommended in disease-free obstetric patients. | 8.40 (2.19) m=9 | ||

Mean; (SD: standard deviation); [I25–I75]=[Interquartile 25–Interquartile 75]; m=median;

N1/N2: question number in the first round/question number in the second round.

MCV: mean corpuscular volume. rHuEPO: recombinant human erythropoietin. Hb: haemoglobin. EACTA: European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery.

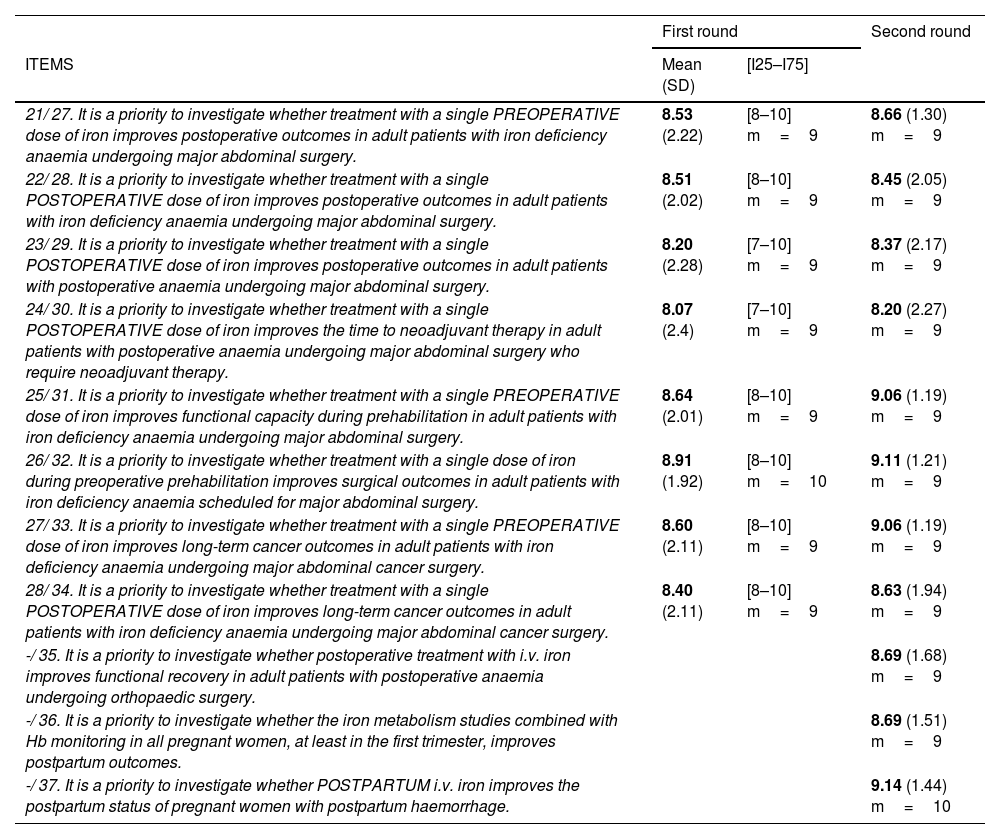

Future lines of research.

| First round | Second round | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ITEMS | Mean (SD) | [I25–I75] | |

| 21/ 27. It is a priority to investigate whether treatment with a single PREOPERATIVE dose of iron improves postoperative outcomes in adult patients with iron deficiency anaemia undergoing major abdominal surgery. | 8.53 (2.22) | [8–10] m=9 | 8.66 (1.30) m=9 |

| 22/ 28. It is a priority to investigate whether treatment with a single POSTOPERATIVE dose of iron improves postoperative outcomes in adult patients with iron deficiency anaemia undergoing major abdominal surgery. | 8.51 (2.02) | [8–10] m=9 | 8.45 (2.05) m=9 |

| 23/ 29. It is a priority to investigate whether treatment with a single POSTOPERATIVE dose of iron improves postoperative outcomes in adult patients with postoperative anaemia undergoing major abdominal surgery. | 8.20 (2.28) | [7–10] m=9 | 8.37 (2.17) m=9 |

| 24/ 30. It is a priority to investigate whether treatment with a single POSTOPERATIVE dose of iron improves the time to neoadjuvant therapy in adult patients with postoperative anaemia undergoing major abdominal surgery who require neoadjuvant therapy. | 8.07 (2.4) | [7–10] m=9 | 8.20 (2.27) m=9 |

| 25/ 31. It is a priority to investigate whether treatment with a single PREOPERATIVE dose of iron improves functional capacity during prehabilitation in adult patients with iron deficiency anaemia undergoing major abdominal surgery. | 8.64 (2.01) | [8–10] m=9 | 9.06 (1.19) m=9 |

| 26/ 32. It is a priority to investigate whether treatment with a single dose of iron during preoperative prehabilitation improves surgical outcomes in adult patients with iron deficiency anaemia scheduled for major abdominal surgery. | 8.91 (1.92) | [8–10] m=10 | 9.11 (1.21) m=9 |

| 27/ 33. It is a priority to investigate whether treatment with a single PREOPERATIVE dose of iron improves long-term cancer outcomes in adult patients with iron deficiency anaemia undergoing major abdominal cancer surgery. | 8.60 (2.11) | [8–10] m=9 | 9.06 (1.19) m=9 |

| 28/ 34. It is a priority to investigate whether treatment with a single POSTOPERATIVE dose of iron improves long-term cancer outcomes in adult patients with iron deficiency anaemia undergoing major abdominal cancer surgery. | 8.40 (2.11) | [8–10] m=9 | 8.63 (1.94) m=9 |

| -/ 35. It is a priority to investigate whether postoperative treatment with i.v. iron improves functional recovery in adult patients with postoperative anaemia undergoing orthopaedic surgery. | 8.69 (1.68) m=9 | ||

| -/ 36. It is a priority to investigate whether the iron metabolism studies combined with Hb monitoring in all pregnant women, at least in the first trimester, improves postpartum outcomes. | 8.69 (1.51) m=9 | ||

| -/ 37. It is a priority to investigate whether POSTPARTUM i.v. iron improves the postpartum status of pregnant women with postpartum haemorrhage. | 9.14 (1.44) m=10 | ||

Mean; (SD: standard deviation); [I25–I75]=[Interquartile 25–Interquartile 75]; m=median.

N1/N2: question number in the first round/question number in the second round.

For the statistical analysis, the mean, median and interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) of the score of each item were calculated and plotted on a graph.

No patient data were used, and the study received no funding.

ResultsA total of 35 experts participated in the 2 Delphi rounds: 60.1% anaesthesiologists, 26.6% haematologists, and 13.3% from other medical specialties (internal medicine and surgery). Over half (64.5%) had more than 20 years’ experience, 31.1% had 10–20 years’ experience, and 4.4% had between 5–10 years’ experience.

The degree of consensus reached by participants on the importance of the PMB recommendations in the RICA Pathway was both strong and homogeneous, as can be seen in Table 1.

Analysis of Delphi roundsAs shown in Table 2A. PREOPERATIVE, in the first Delphi round, the participants achieved a strong consensus, with all items obtaining a score of 8 points except for item 14, in which the word order was reversed with respect to the other items, and in item 13, which concerns the use of recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO) to reduce the transfusion rate in non-iron deficiency anaemic patients.

In the second round, a strong, homogeneous level of consensus was also obtained, with all items obtaining a higher score with the exception of items 13 and 14 mentioned above (Table 2.A.PREOPERATIVE) and items 15 (Table 2.B.POSTOPERATIVE) and 22 (Table 3) concerning the effectiveness of postoperative i.v. iron in patients with low iron stores and/or moderate-to-severe anaemia following bleeding and in patients with iron deficiency anaemia undergoing upper abdominal surgery.

All recommendations were accepted except for the recommendation that clinically stable patients with moderate anaemia (HB 8−10g/dl) should receive preoperative transfusion of packed blood cells (item 14/16 in Table 2.A. PREOPERATIVE).

All but 3 of the remaining items obtained scores of >8 and >9 points from 70% of respondents.

A similar trend was observed in items on future lines of research in both rounds (Table 3), particularly the consensus achieved on the need for clinical trials investigating the effectiveness (measured in postoperative outcomes) of pre- and postoperative treatment and clinical recovery and well-being during pregnancy and in the postpartum period.

DiscussionThe aim of the PBM program is to obtain optimal clinical outcomes by correctly applying evidence-based strategies in a timely fashion to maintain and/or improve Hb values, optimize haemostasis, and minimize perioperative blood loss. PMM is a cost-effective strategy that reduces postoperative complications,3,11 and like enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS), is a patient-centred program for maximising early post-operative recovery.7

There is abundant literature on this topic, one of the pioneering studies being the Spanish statement on alternatives to allogeneic transfusions, known as the ‘Seville document’, originally drafted 2006 using Delphi methodology to classify the grade of scientific recommendations from “A” (supported by controlled studies) to “E” (uncontrolled studies and expert opinion), and subsequently using Grades of Recommendation Assessment (GRADE) methodology to formulate the degree of scientific recommendation.12 Despite the available evidence and the strength of the recommendations, adherence to the guidelines is patchy and scarce.

The Delphi method, developed in the 1950s to reach consensus on military decisions and adapted to Health Sciences in the 1980s by Rand at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), is currently the most methodologically sound method for achieving expert consensus on clinical issues. Its use, both in person and online, reduces the cognitive biases of participants and coordinates, unifies and enhances their collective knowledge. Its effectiveness is evident from the many clinical guidelines that have been drawn up using this methodology, and its reliability is evident from the fact that experts maintain their scientific opinions 6–9 months after reaching consensus.13,14

The Delphi-Rand-UCLA methodology requires a task force, a literature review, and 2 rating rounds, during which an anonymized feedback process brings the opinions of the participating experts closer to consensus. This was the case in our Delphi survey, in which the level of consensus increased in the second round after some of the questionnaire items had been reformulated and items suggested by some experts had been added to the questionnaire.

The main expert recommendations to increase the degree of penetration of the PBM program in routine clinical practice are grouped as follows: One. “It is important and necessary to detect and diagnose the origin of preoperative anaemia in ALL patients scheduled for surgical procedures with potential bleeding risk, including pregnant patients.”

In the recent International Consensus Conference on Anemia Management in Surgical Patients (ICCAMS),15 attendees agreed that the prevalence of preoperative anaemia and its association with worse clinical outcomes justify screening all patients for anaemia before surgery, except those undergoing minor procedures, and that said screening must be for all patients, not only for scheduled patients.

Similarly, several epidemiological studies have suggested that the preoperative haemoglobin cut-off level should be at least 13g/dL,2,3,16 particularly in cardiac surgery patients, regardless of the patient's sex and altitude above sea level. This is higher than that considered by the World Health Organization (WHO).17

It is important to accurately diagnose the origin of preoperative anaemia, despite the difficulties involved. Although iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) with ferritin < 30ng/mL is the most common type of preoperative anaemia, in surgery patients, it is often found alongside anaemia of inflammation, which causes functional iron deficiency due to decreased erythropoiesis.1,18 In these cases, ferritin, an acute phase reactant in inflammation, is elevated, so ferritin <100ng/mL may indicate the coexistence of IDA and anaemia of inflammation. Inflammation alters iron homeostasis by sequestration and penalizes the capacity of the transferrin saturation index (TSI) to indicate IDA.18,19 Determining biochemical indicators of inflammation (e.g. C-reactive protein levels) helps quantify the inflammatory profile of patients in whom the origin of preoperative anaemia is being studied.

Other laboratory parameters that can differentiate between iron deficiency anaemia and anaemia of inflammation are now being incorporated into decision-making algorithms. Reticulocyte Hb content < 29pg indicates IDA, since it is not altered by inflammation.19 Levels of hepcidin (a peptide produced in hepatocytes and released by inflammatory cytokines, which inhibits intestinal iron absorption and macrophage iron release) also help determine the origin of anaemia: hepcidin < 20mcg/L suggests IDA, while higher values indicate anaemia of inflammation.20 Soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) is elevated in IDA and is not influenced by the inflammatory process.18,21

Many pregnant patients present postpartum anaemia, which is defined by the WHO as Hb <11g/dL 7 days after delivery or Hb <12g/dL in the first year of delivery. Prevalence is 22%–50% in developed countries and higher in developing countries. The main causes of postpartum anaemia are iron deficiency and/or IDA before and during pregnancy22 associated with previous vaginal bleeding plus malabsorption during pregnancy, childbirth, or during interventions such as caesarean section. Postpartum anaemia reduces the mother's quality of life due to fatigue, anxiety, and postpartum depression, increases the risk of postpartum bleeding, premature birth, low infant weight and delayed neurodevelopment.23 It has been suggested that gestational and postpartum iron deficiency interferes with normal production of the neurotransmitter dopamine, causing deficiency-induced depression and fatigue.24,25 For this reason, and above all in the interest of quality obstetric health care, the experts believe that hospitals need to draw up protocols for monitoring Hb and ferritin levels in pregnant women and after heavier than normal vaginal bleeding: 500mL after vaginal delivery; 1000mL after caesarean section. Two. “The preoperative treatment of anaemia should be started in advance and should include all the haematinics needed to correct the condition”.

The aim of rescue therapy for preoperative anaemia is to improve preoperative Hb levels and avoid and/or reduce the likelihood of perioperative blood transfusion. Treatment should include the administration of all haematinics identified as deficient and the use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA), if necessary.

To guarantee the effectiveness of this strategy, it should be started in advance - at least 4 weeks prior to surgery. This, however, is not always feasible in urgent major surgery. Nevertheless, clinical experience has shown that shorter treatment periods are also effective and should be considered. There is also reliable evidence that the administration of intravenous iron, subcutaneous erythropoietin alfa, vitamin B12, and folic acid on the day before cardiac surgery26 reduces the transfusion rate in patients with preoperative anaemia. It is never too late to start rescue therapy for preoperative anaemia in patients undergoing any surgery with a potential risk of bleeding.

Iron therapy is the cornerstone of preoperative rescue therapy in obstetric anaemia. It can also be given orally; however, this has several disadvantages in surgical patients, such as gastrointestinal intolerance, poor adherence to treatment (which needs to last at least 6 weeks in order to replenish systemic iron stores), and poor intestinal absorption in patients with inflammation.

For this reason, the first line treatment in preoperative anaemia due to IDA should be i.v. iron, which can be combined with other haematinics if required. The risk of serious adverse reactions to i.v. iron is only 4 per million administered doses of low molecular weight iron dextran and even lower in the case of iron carboxymaltose.27 This far outweighs the risk of an adverse reaction to blood transfusion. Transient hypophosphatemia, a fairly common finding during i.v. iron therapy, does not appear to have any clinical significance.28 Similarly, i.v. iron therapy is not significantly associated with worsening of infection.29 For these reasons, i.v. iron is the gold standard for IDA, but should be used with precaution in patients with known allergy to iron and in cases of unstable sepsis.

Various systematic reviews and meta-analyses evaluating the effectiveness of preoperative i.v. iron have found that although it only achieves a moderate increase in Hb levels both preoperatively and at 4 postoperative weeks, it is associated with a reduction in the rate of perioperative blood transfusions and the rate of infection and postoperative mortality.30,31 Other studies, however, have been less conclusive. This could be due to methodological defects, since systematic reviews include observational studies with small samples. For example, in the PREVENTT study,32,33 which was criticized for its methodology, the authors found no differences in transfusion prevalence or postoperative morbidity and mortality between patients treated with i.v. iron vs placebo. However, Hb values were higher at 8 weeks and 6 months postoperatively, and the readmission rate was lower in the group of patients treated with i.v. iron.

For all these reasons, the experts believe there is a need to prioritise new methodologically appropriate studies and research into establishing the definitive i.v. iron treatment for surgical patients with iron deficiency.

ESAs are used in surgical patients to correct low erythropoietin levels caused by kidney inflammation and to reactivate erythropoietin receptor production that has been depressed due to synthesis deficiency following kidney failure or bone marrow toxicity due to chemotherapy. ESAs enhance the effect of i.v. iron and other haematinics.34 Their effectiveness has been assessed in numerous clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.35,36 In the Seville Document,12 administration of ESAs to correct anaemia in orthopaedic surgery received an A1 recommendation, and their use has been included in various international clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of preoperative anaemia.

Despite this, clinicians are still reluctant to use them in routine clinical practice due to their potential adverse effects. This was reflected in our Delphi study, in which ESA therapy also achieved a relatively low consensus: 8.77 in orthopaedic surgery; 8.66 in cardiac surgery; and 7.46 in major abdominal surgery. This mistrust stems from the 2007 FDA statement warning of the risk of increased deep vein thrombosis and mortality associated with inappropriate dosages in patients with kidney failure or cancer treated with ESAs.37 The fear persists today, despite extensive evidence of the efficacy and safety of ESAs in the literature.35,36

New, methodologically appropriate multicentre studies will probably be required to remedy this situation. Meanwhile, ESAs should be used following certain safety guidelines: in patients with anaemia of inflammation, ESAs should always be administered in combination with i.v. iron to avoid iron deficiency erythropoiesis38; use the ESA preparation with the shortest plasma half-life39; administer the lowest effective weekly dose; do not allow Hb values to exceed 13g/dL; study the risks/benefits of ESAs in each patient; and consider preoperative prophylactic anticoagulation in patients at risk of deep vein thrombosis. Three. “There is NO justification for transfusing packed red blood cells preoperatively in stable patients with moderate anaemia (Hb 8−10g/dL) who are scheduled for surgery with a potential risk for bleeding”.

This statement was unanimously rejected the experts. Transfusion of packed red blood cells is known to be main strategy used to rapidly increase Hb levels in haemodynamically unstable patients with severe anaemia, even though blood transfusion, which goes against the principles of normovolemic haemodilution and controlled restrictive hypotension, increases blood viscosity and blood pressure and promotes bleeding/rebleeding. However, in stable patients with moderate anaemia (Hb 8−10g/dL), transfusion of packed red blood cells promotes postoperative complications in a dose-dependent manner. It should be reserved for patients with severe anaemia (Hb<7g/dL), active bleeding, or symptomatic anaemia.15 Four. “It is recommended to standardise restrictive criteria for red blood cell transfusion in surgical and obstetric patients”.

Clinical experience and numerous clinical studies have demonstrated the benefits of restrictive transfusion criteria in surgical and obstetric patients, and this suggestion achieved a strong consensus among our experts. Only the minimum clinically effective dose12 should be administered, and the patient’s status should be re-evaluated clinically and analytically before further doses are given.

Despite this, misgivings persist regarding the use of restrictive transfusion criteria in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, even among our experts. The use of restrictive criteria in haemodynamically stable cardiac surgery patients with no signs of active bleeding received an overall score of 7.60 from our expert panel. This is far lower than the scores obtained for the use of a restrictive strategy in non-cardiac patients who are stable and have no active bleeding.

The reluctance stems from the risk of postoperative cardiogenic shock in patients treated using restrictive transfusion criteria.40 Fortunately, a recent meta-analysis found no difference in surgical outcomes between restrictive and liberal transfusion criteria in cardiac surgery patients.41 Some researchers have suggested that the transfusion of packed red blood cells itself could be the cause of postoperative kidney dysfunction in diabetic patients with increased NGAL (neutrophil-gelatinase-associated lipocalin) and creatinine levels undergoing coronary surgery.42 This is further evidence of the benefit of restrictive transfusion criteria, even in cardiac surgery patients. Five. “Postoperative anaemia should be treated to improve postoperative outcomes and accelerate postoperative recovery in the short and medium term”.

Perioperative strategies to correct anaemia may be undermined by failure to treat highly prevalent postoperative anaemia in patients undergoing major surgery and in obstetric patients with significant bleeding. This achieved high scores and unanimous agreement among our experts.

Administration of i.v. iron in the immediate postoperative period reduces the prevalence of 30-day postoperative anaemia43,44 and the corresponding need for blood transfusion. So this is a highly cost-effective strategy.45

The 2018 International Consensus statement on the management of postoperative anaemia46 recommends giving i.v. iron to hospitalised patients that have undergone major surgery, discourages the use of oral iron due to the risk of gastrointestinal intolerance and poor absorption, and even suggests administering ESAs in cases of severe anaemia in non-cancer patients with inflammation‐induced blunted erythropoiesis, kidney failure, or in patients who refuse transfusions. Various meta-analyses on postoperative ESAs have highlighted their benefits in patients with inflammation (e.g. severe multiple trauma and critically ill patients). As these patients need prophylactic anticoagulation, they are unlikely to present thrombotic complications that could be attributed to treatment with ESAs.47,48

ConclusionsThe advantages of perioperative PBM programs to optimize surgical outcomes and minimize postoperative complications, mortality, prolonged hospital stays, and readmissions have been clearly demonstrated in the scientific literature. This document will help identify evidence-based initiatives and strategies that can potentially be implemented in all hospitals for all patients.5,6

In conclusion, it is important to emphasise that perioperative anaemia is a disease that complicates and worsens surgical outcomes and is an independent risk factor for postoperative complications, mortality, prolonged hospital stays, and readmissions. Treatment strategies for anaemia are supported by ample scientific evidence and clinical experience.

The next challenge is to reliably verify that PBM also benefits long-term global clinical and oncological outcomes. This will ensure that blood management protocols applied to surgical patients are definitively accepted as the standard of care quality in all hospitals following the RICA Pathway.

FundingThis study has been carried out under the group's own initiative, and has not received any funding.

Conflict of interestsDr García Erce was a representative of the Spanish Society of Haematology and Haemotherapy in the RICA pathway and a member of the RICA task force. Dr Jericó was a member of the RICA pathway collaborative task force, and worked with Dr García Erce in the review of the PBM recommendations.

Roles and responsibilitiesJAGE, AAM, JRM: Conceptualization MLAC: survey design. EBV: dissemination and selection of expert panel. JAGE, AAM, JRM, MLAC, EBV, CJ: first round review, writing second round questions, second round review, conclusions. VM and JAGE: writing manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

All participants in the AWGE-GIEMSA Annual Conference Barcelona 2021 and Málaga 2023. All the panellists.

All the members of the anaemia, haemostasis and transfusion division of the RICA pathway.

Dr García Foncillas, University of Zaragoza, for reviewing the methodology and statistical analysis.

All blood donors.

Ane Abad, María Luisa Antelo, Sonsoles Aragón, Alicia Aranguren, Pilar Arribas, Gonzalo Azparren, Marta Barquero, Elvira Bisbe, Misericordia Basora, Eva Bassas, Jose Luis Bueno, Isabel Castrillo, Gabriel Cerdán, María José Colomina, Virginia Dueñas, Lourdes Duran, Gabriela Ene, Inocencia Fornet, José Antonio García Erce, María José García, Aurelio Gomez, Rosa Goterris, Pilar Herranz, Francisco Hidalgo, Carlos Jericó, José Luis Jover, María Jesús Laso, María Luisa Lozano, Javier Mata, Esther Méndez, María Victoria Moral, Manuel Muñoz, Mar Orts, Javier Osorio, Pilar Paniagua, Teresa Planella, Manuel Quintana, Valle Recasens, Javier Ripollés, Aina Ruiz, Nuria Ruiz, Ramón Salinas, Guillermo Sánchez, Violeta Turcu, José Manuel Vagace, Jose Fancisco Valderrama, M Angeles Villanueva, Gabriel Yanes.

Primary authors.

Work accepted as an oral communication entitled: “Consensus recommendations on the management of perioperative anemia. Delphi-RAND/UCLA Method”, to be defended at the LXV National Congress of the SEHH - XXXIX National Congress of the SETH and III Ibero-American Congress of Hematology, which will be held in Seville, Spain, from October 26 to 28, 2023.