Patients with cleft lip and palate usually present with maxillary hypoplasia. Upper jaw intraoral distraction osteogenesis (DO) is an alternative technique for patients with severe maxillary hypoplasia. An evaluation was made of the changes produced in hard and soft tissues and their stability over time.

Material and methodsSix patients (5 female and 1 male) between 16 and 25 years old with cleft lip and palate underwent maxillary DO with an internal distractor. An evaluation was made of the skeletal and soft tissues changes using cephalometric studies with radiographs and photographs. Follow-up time was between 2 and 8 years.

ResultsThere was Point A advancement between 3 and 10mm in 5 patients, significantly improving maxillomandibular relationships. Intraoral DO failed in one patient, and the case was finished using rigid external distraction (RED). In another patient hardly any advancement and maxillary rotation was observed. The relapse observed between 6 and 9 months post DO was between 10 and 15% in both skeletal and soft tissues.

ConclusionsIntraoral DO is a successful alternative technique in maxillary advancement in patients with cleft lip and palate who need an advancement less than 10mm. It produces improvements in the skeletal and soft profile. Internal devices do not have any psychological impact and have longer consolidation phases. Relapse is difficult to determine and calculate.

Los pacientes fisurados labio palatinos presentan con frecuencia hipoplasia maxilar. La osteogénesis por distracción (DO) de maxilar superior es una técnica alternativa para pacientes con hipoplasia maxilar severa. Se han evaluado los cambios producidos en tejidos duros y blandos y su estabilidad en el tiempo.

Material y métodosSe ha realizado DO de maxilar a 6 pacientes (5 mujeres y un hombre) fisurados labio palatinos, entre 16-25 años, con un distractor interno. Hemos evaluado mediante trazados cefalométricos en radiografías y fotografías los cambios esqueléticos y en tejidos blandos. El tiempo de seguimiento fue entre 2-8 años.

ResultadosEn 5 pacientes el punto A avanza entre 3-10mm mejorando significativamente las relaciones maxilo-mandibulares. En un paciente fracasa la DO intraoral y se termina el caso con RED; en un paciente se evidencia poco avance y rotación maxilar. La recidiva observada entre 6-9 meses post DO es entre el 10 y el 15% tanto esquelética como en tejidos blandos.

ConclusionesLa DO intraoral es una técnica alternativa exitosa para avance del maxilar en pacientes fisurados labio palatinos que necesiten un avance inferior a 10mm. Produce mejoras en el perfil esquelético y blando. Los dispositivos internos no producen impacto psicológico. La contención más larga en el tiempo. La recidiva es difícil de definir y calcular.

In cleft palate patients, the development of dentofacial deformities is more frequent than in the general population, as a result of the malformation itself and of the iatrogenic effects of prior interventions. The most frequent alteration consists of maxillary hypoplasia, appearing after closure of the cleft palate. Most series point to 15–25%, although some even reach 50%. Ultimately, they present a class III, with a concave facial morphology due to multidimensional maxillary hypoplasia, with deficiencies frequently in the sagittal, vertical and cross-sectional planes.1

Over the years, different treatments have been carried out with the objective of achieving a harmonious profile in the face of the cleft palate patient. Thus, for patients still growing, extra-oral forces have been used to correct maxillary retrusion. Once the growth of the facial skeleton was complete, the malocclusion has been treated with osteotomies type Le Fort I, attempting to reposition the maxillary in the sagittal plane and stabilising it with a rigid fixation with or without bone grafts due to its tendency to recurrence. In addition, when the maxillary advancement was over 6mm, treatments with orthognathic bimaxillary surgery have been carried out.2

Currently, distraction osteogenesis (DO) of upper maxillary is an alternative technique for treatment of cleft palate patients with severe maxillary hypoplasia.

Since 1992, when McCarthy published the first work on distraction of craniofacial deformities, numerous articles of middle facial distraction with different types of devices have been published.

In 1997, Polley and Figueroa3 described a new DO technique for patients with severe maxillary hypoplasia using a midfacial, external, adjustable and rigid distractor. In 1998, Molina and Ortiz Monasterio4 published the positive results obtained in cleft palate patients with severe maxillary hypoplasia in mixed dentition phase, using a facial mask with intraoral arch after an incomplete Le Fort I-type osteotomy.

There are several publications describing postoperative changes to hard tissues in patients who have been treated with maxillary DO. However, there are not that many on changes caused to the soft profile of these patients subjected to the same treatment.

The purpose of this study is to assess the skeletal changes and the soft profile after maxillary distraction in adult, cleft palate patients and their stability over time.

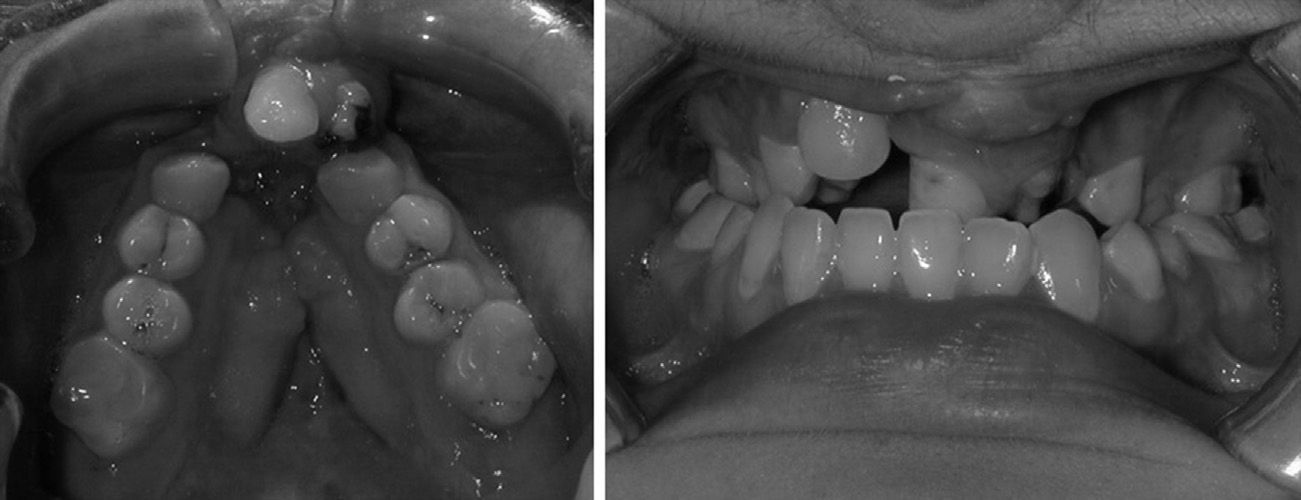

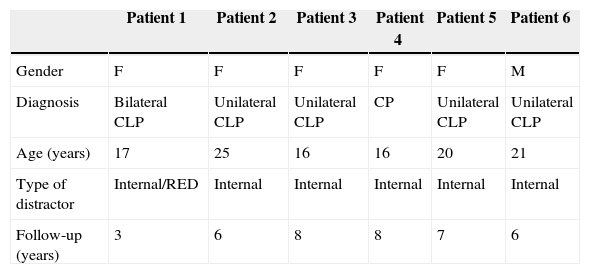

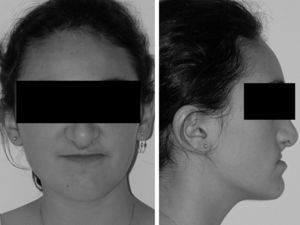

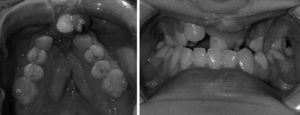

Material and methodsBetween the years 2005 and 2009, bone distraction was performed on 6 adult patients (5 women and one man) with an age-range between 16 and 25 years. Four patients presented complete unilateral cleft lip and palate, one presented only cleft palate, and the other presented a complete bilateral cleft lip and palate. All of them had undergone secondary alveoloplasty between the ages of 10 and 15 with the aim of closing the oronasal fistula, stabilising the bone segments, favouring tooth eruption, and, above all, having a continuous maxillary arch in order to carry out maxillary distraction (Table 1). All patients had severe maxillary hypoplasia, with Angle class III malocclusion (Fig. 1). In some cases, they also presented cross-sectional collapse of the alveolar arch, dental anomalies, scars and fibrosis in the palate from prior surgeries (Fig. 2). In all of them, upper maxillary advancement was carried out by means of osteogenic distraction with internal distractors, except for one case where the internal distractor was not sufficient to advance the maxillary for the desired number of millimetres, which therefore forced the use of an external, rigid distractor. All the patients were orthodontically prepared for distraction by expanding the maxillary, levelling the curves, and aligning and decompensating the teeth, as each case required (Fig. 3). Under general anaesthesia, a Le Fort I-type osteotomy was carried out, with pterygomaxillary and septal disjunction, total mobilisation of the maxillary without down-fracture and insertion of the distractor. For all patients, a stereolithographic model was made, where the surgery was planned, the distractors were modelled with the desired vector, and a template was prepared in order to make the most accurate transference possible of the operative plan based on the stereolithographic model for the patient in the operating room, contributing with precision to the placement of distractors and decreasing operating time.

Description of patients.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | F | F | F | F | M |

| Diagnosis | Bilateral CLP | Unilateral CLP | Unilateral CLP | CP | Unilateral CLP | Unilateral CLP |

| Age (years) | 17 | 25 | 16 | 16 | 20 | 21 |

| Type of distractor | Internal/RED | Internal | Internal | Internal | Internal | Internal |

| Follow-up (years) | 3 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 |

The distraction vector was parallel to the occlusal plane. The latency period was 5 days, the distraction rhythm 0.5mm every 12h and the overcorrection was 2–4mm depending on each case. The support period in patients with internal distractors was over 5 months and, in the case of the patient treated at a second time with rigid external distractor, it was only 12 weeks.

Distractors usedThe internal distractor was the trans-sinusoidal for middle third by KLS Martin. The body of the distractor is inserted in the maxillary sinus through a Cadwell-Luc window. The bone neoformation must be predicted with regard to the Frankfurt plane and the middle line. All the surgical planning is made on the stereolithographic model. Planning simulates both the Le Fort I osteotomy as well as the distraction vector. The device is comprised of an upper plate with a tube where the distractor screw goes through. The plate is adapted to the model and it is placed provisionally with 2 screws. The lower plate carries the distraction screw that is inserted in the maxillary sinus. Once the upper plate is placed and the window to the sinus is made, the lower plate is placed with the distraction screw, without attaching it and the osteotomy line is marked. The transference in the operating room of all the planning performed is made by means of a resin template that will be placed in the maxillary where the distractor screw goes to the maxillary sinus through the tube of the upper plate, which in reality determines the direction of the distraction vector; the template also indicates the placement of the upper plate, which is frequently located at the level of the infraorbital nerve, which must on occasion be dissected.

- -

The rigid, external distractor used was model RED II by KLS Martin.

The diagnosis study consisted of a lateral and frontal teleradiography of the skull, orthopantomograph, study models, clinical photographs, and the making of a stereolithographic model.

The follow-up time was between 2 and 8 years after distraction.

All patients had a lateral and frontal teleradiography of the skull and profile photographs before the distraction (T0), at the end of distraction (T1), 6 months after (T2) and at least 36 months after finishing treatment (T3).

Each and every X-ray and photograph taken from the patients was analysed for the bone and soft tissues assessment. All measures were taken by the same investigator manually and on acetate paper for cephalometric tracing. Thus, by overlapping the tracing, the advancement of maxillary achieved by means of distraction can be evidenced (T0 and T1), as well as the stability over time of the bone structures and the soft tissue in the middle-facial region in mid term (T1 and T2) and in long term (T3).

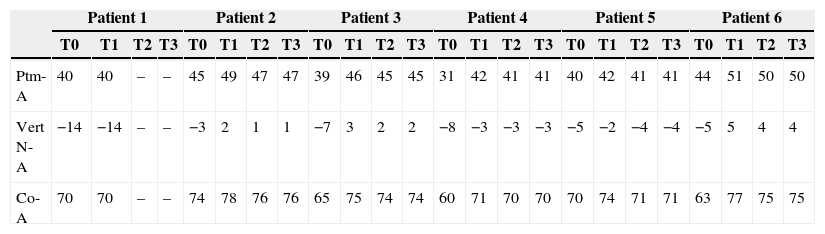

The teleradiographies taken from the patients were used for the cephalometric analysis and 3 linear measurements were assessed, showing the advancement of the upper maxillary with regard to 3 bone structures fixed during the distraction process: the pterygomaxillary fissure, the nasion and the mandibular condyle (Table 2).

- -

Ptm-A: linear distance between the pterygomaxillary fissure and point A projected perpendicularly on the Frankfurt (FH) plane.

- -

Vert N-A: linear distance between point A and the McNamara vertical (perpendicular to FH passing through nasion).

- -

Co-A: linear distance between the condyleon and point A projected perpendicularly on the Frankfurt (FH) plane.

Results of skeletal analysis during intervals T0, T1, T2 and T3 with regard to each of the others during the follow-up period of distraction.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| Ptm-A | 40 | 40 | – | – | 45 | 49 | 47 | 47 | 39 | 46 | 45 | 45 | 31 | 42 | 41 | 41 | 40 | 42 | 41 | 41 | 44 | 51 | 50 | 50 |

| Vert N-A | −14 | −14 | – | – | −3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | −7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | −8 | −3 | −3 | −3 | −5 | −2 | −4 | −4 | −5 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Co-A | 70 | 70 | – | – | 74 | 78 | 76 | 76 | 65 | 75 | 74 | 74 | 60 | 71 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 74 | 71 | 71 | 63 | 77 | 75 | 75 |

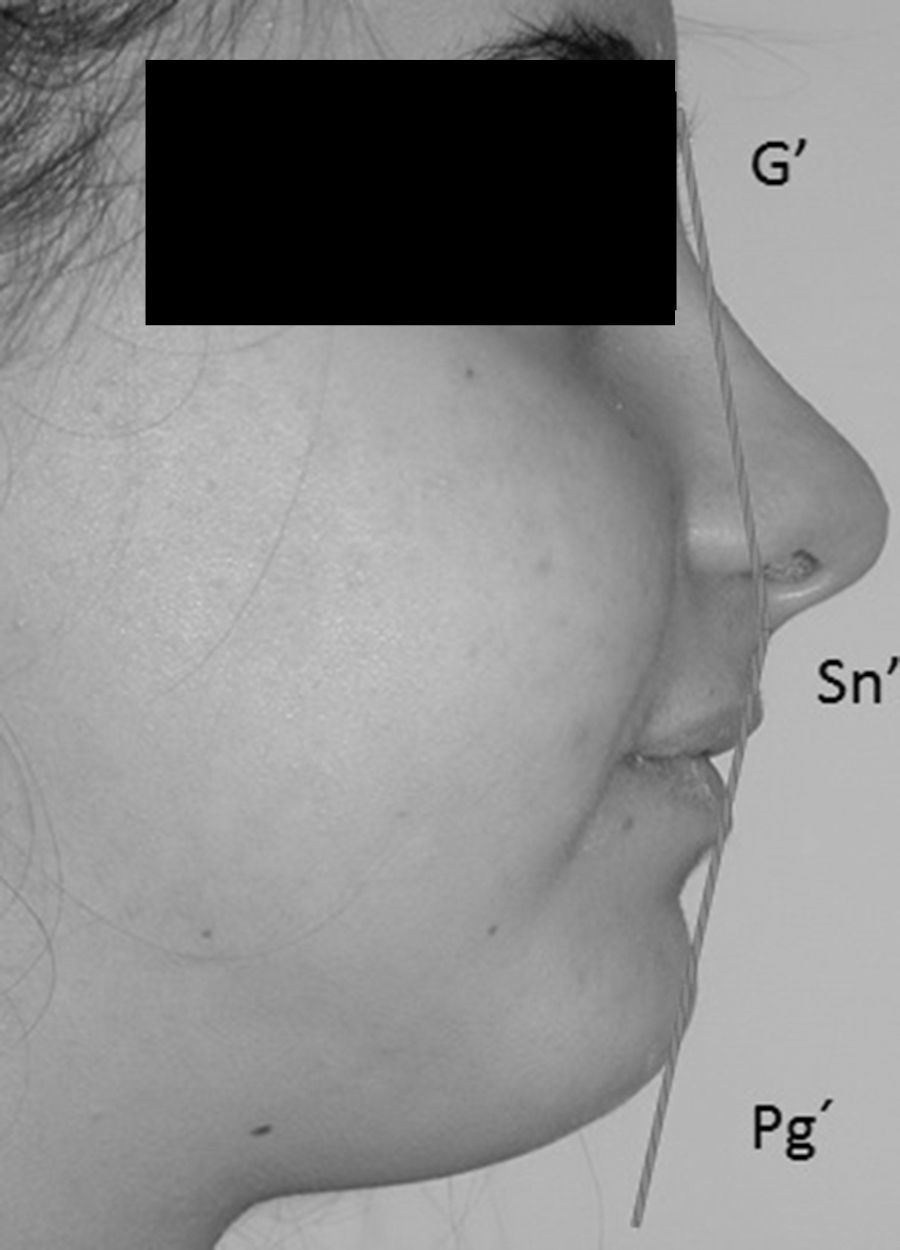

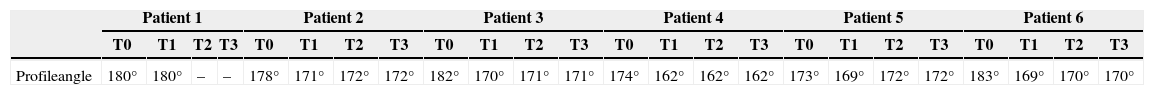

For the analysis of soft tissues, the profile angle of Arnett and Bergman was measured in the profile photographs. Said angle represents the most important measurement of soft tissue and it locates the mandible and the maxillary anterioposteriorly with what may qualify a patient for skeletal class I, class II and class III. It is formed by the G’ point (soft glabella), Sn (utmost posterior point of sub-nasal columella) and Pg’ (soft pogonion).

- -

165–175°: normal patient, skeletal class I (balanced ratio and general harmony between forehead, middle and lower thirds).

- -

<165°: skeletal class II with convex profile.

- -

>175°: skeletal class III with concave profile.

As the angle grows farther from these measures, the bone discrepancy will be greater and may be considered as severe (Table 3).

Results of the analysis of soft tissues during intervals T0, T1, T2 and T3 with regard to each of the others during the period.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| Profileangle | 180° | 180° | – | – | 178° | 171° | 172° | 172° | 182° | 170° | 171° | 171° | 174° | 162° | 162° | 162° | 173° | 169° | 172° | 172° | 183° | 169° | 170° | 170° |

In 5 patients, by the end of the distraction period (T1), the clinical exam shows a satisfactory advancement of the maxillary with regard to the start of this study (T0), significantly improving the maxillomandibular skeletal relationship. The maxillary, point A, advanced between 3 and 10mm measured from the pterygomaxillary (Ptm–A), the McNamara vertical (Vert N–A) and the condyleon (Co–A).

The cephalometric analysis, 6 months after distraction (T2), shows a loss of between 10–15% of the obtained improvement; this translates into a loss of maxillary advancement, point A, of approximately 1mm. This recurrence maintains stable over time, with changes being minimal and even imperceptible at least 2 years after distraction (T3).

Changes in soft tissues of the 5 patients where distraction has caused advancement of the maxillary show the same pattern of improvement and the same pattern of recurrence that in the facial skeleton. Thus, it is observed that between the start (T0) and the end of distraction (T1), the profile has grown more convex and the upper lip has projected, improving its relationship with the lower lip. The profiles have shifted from being characteristically class III to showing a more balanced and harmonic relationship between the forehead, the middle third and lower third. Likewise, between the end of distraction (T1) and the subsequent 6 months (T2), 10–15% of the improvements on soft tissue have been lost; following the first 6–9 months after distraction, the results have remained stable (T3) (Figs. 4 and 5).

In one of the patients (patient 1 of Tables 2 and 3) there was a failed maxillary distraction with internal distractor. During the time of the bone distraction, the maxillary did not advance. It was a patient with complete bilateral cleft lip and palate, with very fibrous scars in the palate and upper lip. From the McNamara vertical to point A, there was −14mm of maxillary retrusion. At the time of removing the internal device, a RED system was placed with which an advancement of point A of 16mm was achieved, obtaining a correct maxillomandibular relationship.

For another patient (patient 5 of Tables 2 and 3), distraction only managed to move point A by 3mm. She was a patient with complete unilateral cleft lip and palate, with a 5mm retrusion and anterior open bite. During bone distraction, the anterior open bite was closed, the upper maxillary rotated clockwise, achieving an added positive effect with the small advancement obtained.

DiscussionBone distraction is a treatment option for patients with cleft lip and palate to achieve the correction of hypoplasia of the middle third of the face.5 It may be applied both to patients still growing, as well as adults. Conventional orthognathic surgery with or without bone grafts is another treatment alternative only in patients with complete growth. Bone distraction presents major advantages than other conventional osteotomies: DO in children still growing achieves the expansion of the working matrix and the required tissue regeneration in order to compensate for the growth deficit, for these patients lack both bone as well as soft tissues and distraction of bone structures of the middle facial third is a basis for the expansion of suprajacent tissues. There is no limitation to the advancement of surrounding soft tissues as there may be with the traditional Le Fort II and III procedures, and therefore there is less recurrence to take into account, with results more stable over time.

All our patients had completed their growth, therefore we avoided the most difficult aspect of preoperative planning, which is the prediction of future growth, since mandibular growth is the reason of the increased SNB angle and therefore a decreasing overjet value during the active growth time remaining for the patient.

The 5 patients with satisfactory advancement of their maxillary by means of intraoral distraction did it with an intra-sinus internal distractor and Le Fort type I osteotomy (Fig. 6). The required advancement was less than 11mm.

The advancement limitation in one of the patients was due to the strong resistance of soft tissues as a result of the formation of a scar in the palate and upper lip, secondary to prior surgeries. In addition, in one of them the required advancement was 14mm and the internal distractor was shown to be insufficient.

Scars following the repair of the labial fissure and after velofaringoplasty should not be underestimated. They may not only be the reason for insufficient maxillary growth and underdevelopment of the middle facial third6, but also the cause for maxillary rotation during distraction and even stoppage during the course of the same, such as what occurred in one of the patients with very fibrous scars in the lip and palate, whose internal distraction failed. One of the cases was redirected by means of external distraction with RED, obtaining the desired advancement.

Other factors contributing to failure are insufficient bone support to anchor the internal distractor, bending of distraction devices, and that the vector may only be defined during the installation of the same and cannot be changed once it is placed. In addition, internal devices are difficult to insert, as they are bilateral and need to be parallel to each other. In essence, the 2 internal distractors may move the maxillary in a straight line, but they are not designed for the advancement that also requires a certain rotation movement.

Recent studies suggest that results in maxillary distraction among cleft adults by means of internal distractors are successful.7–9

However, there are other works with disappointing results,10 where the distractor is shown to be ineffective to achieve the desired advancement and to achieve facial convexity and overbite.

Gaetano et al.11 note that during distraction, there is a rotation of the maxillary at the same time that there is advancement. The upper maxillary has a resistance centre (RC). The RC is in a perpendicular line to the occlusal plane, sagittally between the distal contact of the first permanent molar and vertically half the distance from the inferior orbital edge and the occlusal plane. When we apply distraction force under the RC, the upper maxillary turns counter clockwise, with a tendency towards the anterior open bite, and if the distraction force is applied over the RC, the maxillary turns clockwise. Therefore, the distraction vector will be planned considering the rotating maxillary and considering the facial growth pattern and prior occlusion. In deep bites with low gonial angle, we will plan a vector below the rotation centre, and in divergent faces with gingival smile, a vector above the RC would be contraindicated since it would increase gingival exposure. For patients with open anterior bite, we would plan a vector above the RC that would rotate the maxillary clockwise and would close the bite.

In one of the study patients, we observed that during maxillary advancement, the open anterior bite of the patient was closed. This effect, together with advancement, was not interpreted by us at the time, until we read the studies by Gaetano. And because there was clockwise rotation of the maxillary that closed the open bite, we must have applied a distracting force above the RC of the upper maxillary without really being aware of it and it turned clockwise.

We wonder if the advancement of the upper maxillary after bone distraction is stable over time. There are studies documenting stability.12,13 Other authors document the recurrence that is usually caused during consolidation phase.9,14,15 In our study, after an average follow-up of 5 years, we saw that recurrence, both in bone as in soft tissue, took place between 6 and 9 months after distraction and afterwards, the results remained stable, despite certain relapse at the occlusal level (Fig. 7). An active orthodontic treatment is required to ensure the success of distraction.

It is possible that the contraction of the wound plays a major part in recurrence. The impact of final occlusion should also be considered; patients with an anterior open bite have shown more relapse. Obtaining overbite and overjet is the key to occlusal stability (Fig. 8) and to decreasing the relapse amount.

Another variable contributing to stability is the support time. It should be as extensive as possible to increase the mineralisation period of the newly-formed bone.16 The duration of this period is controverted and it depends on the exact location of the osteotomy line and the quality of the distracted bone. The philosophy is: the longer the bone elongation, the longer the support time. The trend is that retention lasts for 3–4 months at least. Support time with our patients has been between 5 and 6 months, except in the case that ended up with RED (Fig. 9) where we only managed to keep the patient in the support period for 12 weeks.

The RED system has fewer limitations with regard to the amount and direction of maxillary advancement. However, the patient has to use a relatively large device, which is fixed to the lateral temporal area for a long period of time, including the support time, and it may become a major cause of postoperative complications caused by psychological stress and the potential risk of accidental injury to the head.

The internal distractor,17 in turn, offers some benefits with regard to postoperative complications because it causes less psychological stress and requires shorter hospitalisation. Internal distractors do not necessarily require the cooperation of the patient during the support period. However, they need to be removed, i.e., a second surgical intervention is needed. It becomes particularly troublesome to remove the plates, especially the cranial one at the level of the lower orbital edge, because a large fibrosis develops around the device. Sometimes there is hypoesthesia of the infraorbital nerve and residual swelling in the facial soft tissue that on occasion may take a while to resolve. Extra-oral devices are not easy to maintain for a long time due to the difficulty of psychological acceptance and the impossibility of leading an everyday life within normal parameters, but they are in turn easier to remove.

ConclusionsInternal DO is a successful alternative technique for maxillary advancement in cleft lip and palate patients that require an advancement under 10mm. It causes improvements in the skeleton profile and in the soft tissue, increases the nasolabial angle and the inferior facial height. Internal devices do not cause psychological impact and allow for a longer support over time. Recurrence is difficult to define and calculate. Overbite and overjet are key to occlusal stability.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

We thank Dr. Lidia Gómez Alonso, orthodontist, for her participation in the making of cephalometric traces on clinical X-rays and photographs.

Please cite this article as: Martínez Plaza A, Menéndez Núñez M, Martínez Lara I, Fernández Solís J, Gálvez Jiménez P, Monsalve Iglesias F. Avance maxilar en pacientes fisurados labio palatinos con distractor intraoral. Rev Esp Cir Oral Maxilofac. 2015;37:123–131.