The aim of this study is to determine the epidemiological features, clinical presentation, and treatment of children with septic arthritis.

Material and methodA retrospective review was conducted on a total of 141 children with septic arthritis treated in Hospital Universitario La Paz (Madrid) between the years 2000 to 2013. The patient data collected included, the joint affected, the clinical presentation, the laboratory results, the appearance, Gram stain result, and the joint fluid culture, as well as the imaging tests and the treatment.

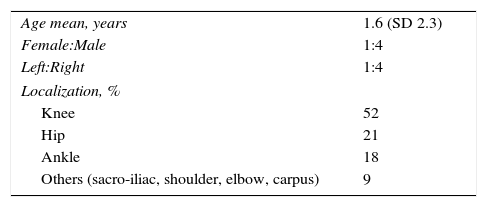

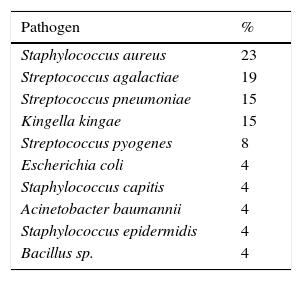

ResultsMost (94%) of the patients were less than 2 years-old. The most common location was the knee (52%), followed by the hip (21%). The septic arthritis was confirmed in 53%. No type of fever was initially observed in 49% of them, and 18% had an ESR (mm/h) or CRP (mg/l) less than 30 in the initial laboratory analysis. The joint fluid was purulent in 45% and turbid in 12%. The Gram stain showed bacteria in 4%. The fluid culture was positive in 17%. Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen found, followed by Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Kingella kingae. Antibiotic treatment was intravenous administration for 7 days, followed by 21 days orally. Surgery was performed in 18% of cases.

ConclusionsThe diagnosis was only confirmed in 53% of the patients. Some of the confirmed septic arthritis did not present with the classical clinical/analytical signs, demonstrating that the traumatologist or paediatrician requires a high initial level of clinical suspicion of the disease.

El objetivo de este estudio es determinar las características epidemiológicas, la presentación clínica y el tratamiento de los niños con artritis séptica en nuestro medio.

Material y métodoSe revisaron retrospectivamente 141 niños con una artritis séptica tratados en el Hospital Universitario La Paz (Madrid) entre los años 2000 y 2013. Se recogieron datos relativos al paciente, la articulación afectada, la presentación clínica, los valores analíticos, el aspecto, la tinción Gram y el cultivo del líquido articular, las pruebas de imagen y el tratamiento.

ResultadosEl 94% de los pacientes eran menores de 2 años de edad. La localización más frecuente fue la rodilla (52%), seguida de la cadera (21%). La artritis séptica se confirmó en el 53% de los pacientes. El 49% de ellos no presentaron fiebre ni febrícula inicialmente y el 18% tenían una VSG (mm/h) o PCR (mg/l) menor de 30 en la analítica inicial. El líquido articular fue purulento en el 45% de los casos y turbio en el 12%. La tinción Gram mostró bacterias en el 4%. El cultivo del líquido fue positivo en el 17%. Staphylococcus aureus fue el patógeno más frecuente, seguido de Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pneumoniae y Kingella kingae. La antibioterapia se administró por vía intravenosa 7 días, seguido de vía oral 21 días. Se realizó una cirugía en el 18% de los pacientes.

ConclusionesLa confirmación diagnóstica solo se obtuvo en el 53% de los pacientes. Algunas artritis sépticas confirmadas no presentaron el cuadro clínico/analítico clásico, por lo que es necesario un alto índice de sospecha inicial de la enfermedad por parte del traumatólogo o del pediatra.

Childhood septic arthritis is a disease having disastrous consequences if not treated early.1–3 Clinical suspicion is important in making an early diagnosis that enables early treatment to be undertaken. Nevertheless, there is wide variability in the management of this illness.2,4–10 Our institution follows a clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of septic arthritis.11 The aim of this study is to determine the epidemiological characteristics, clinical presentation, aetiology, and treatment performed in children with septic arthritis in our setting, assessing the clinical guideline currently in use at our hospital, the “La Paz” University Hospital (Madrid).

Material and methodsThis is a retrospective study that includes 141 patients under 14 years of age with a diagnosis of septic arthritis and who received care at our hospital between 2000 and 2013.

The clinical guideline for the management of septic arthritis in children followed in our hospital11 involves performing a radiograph and ultrasound of the affected joint, as well as blood tests including a full blood count and acute phase reactants (VSG and PCR) in any patient in whom septic arthritis is suspected. Arthrocentesis or arthrotomy (it is not clear who should make the decision as to which one to perform) should be carried out in those cases with a VSG (mm/h) or PCR (mg/l) over 30. In those cases in which purulent synovial fluid is obtained, the patient should be admitted with empirical intravenous antibiotic treatment. On the other hand, in those cases in which non-purulent synovial fluid is obtained or if it cannot be obtained within the first 48h of clinical onset, depending on the patients’ signs and symptoms, the decision will be made as to whether to admit them with antibiotic treatment or refer them to the Paediatric Rheumatology outpatient clinic. The guideline does not stipulate if Paediatric Traumatology should evaluate the patient at some point, when surgery is called for to clean the joint, which service should be in charge of admitting the patient, or who should do the follow-up of the patient and for how long.

Patients’ demographic details are recorded, as well as the joint affected, date of symptomatic onset, data about the clinical debut (possible general involvement, body temperature at the time of admission, the presence of inflammatory signs, ability to bear weight, and limited movement of the affected limb), and the blood test results: white blood-cell count, PCR, and VSG. In those cases in which arthrocentesis was performed, the aspect of the synovial fluid, the result of the biochemistry of the synovial fluid, Gram stain, and microbiological culture are all recorded. Similarly, data regarding treatment collected include the antibiotic administered, mode of administration and treatment duration, as well as whether or not arthrotomy was performed to lavage the joint. All the patients were initially assessed by a paediatrician and admitted to the children's hospital under the responsibility of General Paediatrics, Paediatric Rheumatology, Paediatric Infectious Diseases, or Paediatric Traumatology. A record is made of the department that took charge of the admission.

Retrospectively, a diagnosis of septic arthritis is considered to be confirmed when synovial fluid culture or samples taken during arthrotomy are positive, when the presence of bacteria is established by synovial fluid Gram stain, or when arthrocentesis reveals purulent synovial fluid. The presence of possible sequelae reported in the literature has been assessed.

ResultsThe study includes 141 patients with a mean age of 1.6 years (median 1.1), 94% of whom were under 2 years of age. The demographic data of the sample are presented in Table 1. The most common location was the knee (52%).

Insofar as clinical debut is concerned, 29% of all patients displayed an inability to walk or limited mobility of the affected joint. At the time of presentation at the Emergency Department, 47% of all the cases were fever-free, 16% had fever (mean 38.7°C), and 37% had low-grade fever (mean 37.6°C). The initial analysis revealed the following mean values: 15,077 leukocytes (SD 4960), VSG 59 (SD 26.5) mm/h, and PCR 46 (SD 48) mg/l. None of the patients had previously undergone orthopaedic surgery; hence, the route of dissemination was believed to be haematogenous in all cases.

The affected joint was examined by ultrasound in 47% of all patients, with the presence of joint effusion shown in 39% of the entire series. Arthrocentesis was performed in 80% of all patients; the fluid was seen to be purulent in 57% of them, bloody in 1%, normal in 17%, and unknown (not recorded in the history) in 25%.

Gram stain of the synovial fluid was carried out in 51% of all cases and was positive in only 10% of the 72 cases in which it was performed (7 patients). The synovial fluid was cultured in 77% of all patients and positive in only 24 (17% of the total). The pathogens identified in the cultures are reported in Table 2.

Pathogens identified in the microbiological cultures.

| Pathogen | % |

|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 23 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 19 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 15 |

| Kingella kingae | 15 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 8 |

| Escherichia coli | 4 |

| Staphylococcus capitis | 4 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 4 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 4 |

| Bacillus sp. | 4 |

Retrospectively, in line with the criteria presented in the “Material and Methods” section, we confirmed the presence of septic arthritis in 74 patients (53% of the entire series): 24 with a positive culture (17% of all cases), 7 patients with bacteria on the Gram stain (5% of the total), and 65 patients with purulent synovial fluid (46% of all patients).

As regards body temperature, we must point out that 49% of all patients (69 cases) did not have fever or even low-grade fever at the time they presented at the Emergency Department; and that in half (34 patients; 24% of all the cases), we retrospectively verified the diagnosis of septic arthritis: 29 patients based on purulent synovial fluid, 4 patients on the presence of bacteria on the Gram stain, and 11 patients on the basis of a positive synovial fluid culture (Streptococcus agalactiae in 4 cases, Streptococcus pneumoniae in one case, unspecified Streptococcus in one case, Staphylococcus capitis in one case, unspecified coagulase negative Staphylococcus in one case, Bacillus sp. in one case, and Kingella kingae in 2 cases). With respect to these 34 patients with confirmed septic arthritis but who did not initially present with fever or low-grade fever, acute phase reactants were elevated (VSG [mm/h] >30 or PCR [mg/l] >30) in 28 patients (38% of all patients with diagnostic confirmation; 20% of all patients) and would therefore have been picked up by the clinical guideline; whereas 6 patients (8% of all patients with diagnostic confirmation; 4% of the entire series) displayed VSG (mm/h) or PCR (mg/l) values of less than 30 and would therefore not have been diagnosed with septic arthritis according to the criteria in our clinical guideline; hence, they would have been treated as false negative in the clinical guideline.

Insofar as acute phase reactants are concerned, we must underscore the fact that when presenting at the Emergency Department, 17% of all patients (24 cases) had VSG (mm/h) or PCR (mg/l) values of less than 30 and that we were able to diagnose septic arthritis retrospectively in half of them (13 patients, 9% of all patients): 12 patients due to purulent synovial fluid and 5 based on a positive synovial fluid culture (S. agalactiae, Streptococcus pyogenes, S. capitis, Escherichia coli, and K. kingae). Therefore, 13 patients with confirmed septic arthritis had VSG (mm/h) and PCR (mg/l) levels under 30 in the initial analysis. The mean white blood cell count of these 13 patients was 11,861 (range 7020–20,000) and all of them exhibited low-grade fever upon arrival at the Emergency Department.

In contrast, 6% of all patients should not have been diagnosed with septic arthritis according to the clinical guideline, given that they did not have fever or even low-grade fever at the time of admission; they had VSG (mm/h) and PCR (mg/l) levels of less than 30, non-purulent synovial fluid, absence of bacteria on Gram stain, and negative synovial fluid culture.

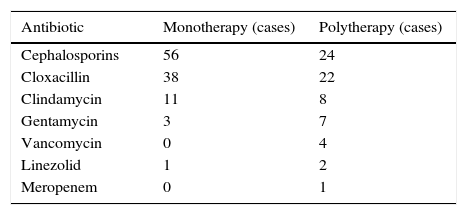

Antibiotic treatment was initially administered intravenously in 96% of cases for a mean of 6.7 days (SD 5; median 5), followed by oral administration for a mean of 21 days (SD 7.5). Four per cent of patients received oral antibiotics from the beginning.

The antibiotics prescribed are reflected in Table 3. Seventy per cent of the patients received treatment with a single antibiotic. Cephalosporin antibiotics were the most widely used (57%) and the most common combination antibiotic therapy was penicillin plus a cephalosporin (41%), the most common association being cloxacillin together with cefotaxime.

Arthrotomy was performed in 18% of the cases (25 patients), with a mean delay of 1.8 days (SD 3.5; median 1) from the onset of symptoms: 16 hips, 7 knees, one ankle, and one elbow.

The service in charge of the patient was Paediatric Rheumatology in 86% of the patients, Paediatric Traumatology in 7%, Paediatric Infectious Diseases in 4%, and General Paediatrics in 3%. Paediatric Traumatology was consulted in 27% of the patients that were not under their direct care.

DiscussionSeptic arthritis continues to be uncommon in our setting, with greater involvement of the weight-bearing joints, such as the knee or hip. In our series, the most frequently affected joint was the knee, followed by the hip, in line with most of the series published.1,8,10 However, other authors have found the hip to be involved more often than the knee.9 In any case, all the series coincide in that the lower limbs are more often affected than the upper limbs.1,8–10

Most of the patients affected in our series were under the age of 2 years (94%), as in most of the series reported in the literature.1,8,9,12 The route of infection is haematogenous in most cases of osteomyelitis and septic arthritis.7

The clinical debut of septic arthritis generally includes fever, weakness, immobility or inability of the affected joint to bear weight. The symptoms and signs in small children are largely unspecific, such as swelling, loss of movement in the joint affected, excessive crying when being held by parents, or limping or the inability to walk when the lower limbs are affected.8,12 In our series, 29% of the patients exhibited loss of joint mobility or the inability to bear weight and only 16% of patients exhibited fever. We believe that it should be pointed out that 46% of the patients with retrospectively confirmed septic arthritis did not present fever or low-grade fever at the time of presentation at the Emergency Department. Staphylococcus aureus was not the causal pathogen in any of the cases in which diagnosis was confirmed and there was no fever or low-grade fever. It is possible that other pathogens having low aggressiveness cause less florid clinical manifestations. It is therefore a good idea to bear in mind that the clinical picture may be subtle and the paediatrician may need to have a high initial suspicion of the disease.

On the other hand, transient synovitis typically presents a history and clinical debut similar to that of septic arthritis and it can often be difficult to establish the differential diagnosis between these two diseases.13 Furthermore, transient synovitis is far more common than septic arthritis. In 1999, Kocher et al.14 presented four clinical and analytic parameters with high predictive power for the diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip. These parameters included fever above 38.5°C, inability to walk on the affected limb, white blood-cell count greater than 12,000cells/ml, and VSG over 40mm/h. Later, Levine et al.15 found that PCR was the best independent parameter to determine the presence of infection. Caird et al.,16 in 2006, added PCR >20mg/l to Kocher et al.’s 4 parameters.14 According to the authors, the likelihood of a child presenting septic arthritis of the hip is 99% if 4 of these 5 criteria are present. The problem lies in that these criteria were only developed for hip involvement and not for the rest of joints. Moreover, other authors have found 20% sensitivity and a positive predictive value of only 60% for septic arthritis when all 5 criteria are present.13 In any case, in the event of diagnostic doubt, arthrocentesis should be performed and the synovial fluid cultured.3

The clinical guideline in use at our hospital establishes that when facing a suspicion of septic arthritis, laboratory analyses and imaging studies (ultrasound and/or simple radiograph of the joint) should be ordered. VSG has proven greater positive predictive value if combined with PCR.16,17 If the analysis reveals PCR and/or VSG values above 30, septic arthritis should continue to be studied. If not, the paediatrician should think about other diseases. The analysis performed in the Emergency Department showed elevated VSG and/or PCR levels in 83% of our patients. Only 52% of patients with increased VSG and/or PCR values had septic arthritis that was confirmed respectively. In contrast, 18% of patients with confirmed septic arthritis had VSG or PCR of less than 30 in the initial analysis. Furthermore, 8% of the patients with a septic arthritis that was retrospectively confirmed had no fever of any kind at the time of admission, nor did they present VSG or PCR values greater than 30 in the initial blood work. The paediatrician or traumatologist must have a high degree of clinical suspicion if septic arthritis is to be diagnosed early on.

As for imaging studies, a simple radiograph may not show any alteration for the first few days of the disease.4 Articular effusion, however, can be seen on ultrasound from the very beginning, thereby excluding other problems. The drawback of ultrasound is that it is observer-dependent and that, while it reveals the existence of effusion, it is not capable of differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis.5,6 In our series, ultrasound was only performed in 47% of cases and effusion was apparent in the vast majority of them.

The analysis of synovial fluid and its culture must be systematically performed as part of the diagnostic workup, with the purpose of establishing proper treatment.3 In our hospital, synovial fluid was only cultured in 77% of the patients, yielding a positive result in only 22% of them. This rate of positive cultures is lower than rates published by other authors (55%).7 Some recommend combining haemoculture with synovial fluid culture to have greater evidence of the bacterial aetiology.7 However, we have not collected blood culture data because this was not routinely carried out.

Microbiological analyses proved the most commonly found pathogen in the cultures of our patients was S. aureus, followed by S. agalactiae, S. pneumoniae, K. kingae, and S. pyogenes. These findings are similar to those published by other authors.2–4,8–10,18 Classically, the pathogens most often involved in septic arthritis in children are Haemophilus influenzae, followed by Staphylococcus and Streptococcus.3,7 Infections caused by H. influenzae have fallen drastically since the vaccine against it was produced in 1980.3 We did not obtain any positive culture for H. influenzae. However, as other authors have pointed out,1,2,4,10 positive cultures for more aggressive pathogens such as K. kingae are appearing more and more.

In our series, the diagnosis of septic arthritis was retrospectively confirmed when the synovial fluid was positive in microbiological culture, contained bacteria as per Gram stain, or appeared to be purulent. In accordance with these criteria, 53% of the patients had confirmed septic arthritis; our rate of over-diagnosis was high (47%). In contrast, our rate of positive cultures (22%) is much lower than that reported for other series (55%),7 which could mean that samples are not being properly obtained or managed. In any event, given the importance of early treatment in septic arthritis, it is better to have a certain degree of over-diagnosis than for cases to be diagnosed late.

With respect to treatment, arthrotomy, in combination with antibiotic treatment, has typically been considered the treatment of choice for septic arthritis.4 Many authors feel that appropriate antibiotic therapy is insufficient2,8 and surgical decompression of the joint is essential to prevent destruction of the cartilage and the underlying epiphysis. However, recent studies conclude that surgery can be foregone when proper antibiotic therapy is initiated.8,9 In our series of patients, arthrotomy was only performed in 18% of cases. This percentage is similar to the 26% published by Al Saadi et al.8 It is important for arthrotomy to be undertaken within the first 4 days of the onset of symptoms to avoid significant, long-term sequelae. Arthrotomy was accomplished in our series with a mean delay of 1.8 days from symptomatic onset. Still, the follow-up of our patients is short and we cannot evaluate the possible sequelae on the epiphysis or cartilage of the joint in question.

Another point of controversy has been the duration of antibiotic treatment and the route for administration. The antibiotic must initially be administered intravenously in order to reach an optimal concentration in the vascular plexus surrounding the joint as soon as possible.3,19 Converting to oral administration of antibiotic therapy has been recommended as soon as the patient has been fever-free for more than 24h, the effusion has improved, and the range of movement of the joint and PCR have normalized.10 At present, converting to the oral route of administration after one week and maintaining it for another 3 or 4 weeks appears to be the regime of choice.10 In our series, intravenous antibiotic treatment was maintained for a mean of 6.7 days in all patients, transitioning later to oral administration for a mean of 21 days. Nevertheless, recent studies do not detect differences in the efficacy of the antibiotic treatment depending on duration9,10; consequently, it seems that the duration of antibiotic treatment could be decreased in those cases that follow a good clinical and analytical course.

The limitations of the study include those inherent to its retrospective nature, the lack of blood cultures, the fact that our criteria for diagnostic confirmation may exclude cases with septic arthritis due to a pathogen having low aggressiveness, or the lack of patient follow-up over the medium term. A long-term evaluation of our patients must be conducted to determine the true incidence of sequelae.

In conclusion, cases of confirmed septic arthritis were found that did not display the typical clinical/analytical presentation. For that reason, the paediatrician or traumatologist must have a high degree of clinical suspicion if septic arthritis is to be diagnosed early and to prevent sequelae.

Level of evidenceLevel IV evidence.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animal subjectsThe authors state that no experimentation on human beings or animals have been conducted for the purposes of this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that they have followed the protocols of their workplace regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors state that this article contains no patient data.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Moro-Lago I, Talavera G, Moraleda L, González-Morán G. Presentación clínica y tratamiento de las artritis sépticas en niños. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:170–175.

This study was presented at the Sociedad Española de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología Annual Congress held in Valencia on September 23rd–25th, 2015.