Review of the cases of discitis treated in our unit in children under 3 years old.

Materials and methodsA retrospective medical record review was made of 10 cases with a diagnosis of discitis at discharge, in children hospitalized from January 1998 to December 2010.

ResultsThe most affected level was L5-S1 (4 cases), followed by L4-L5 (3 cases). The history at presentation was non-specific and caused a delay in the diagnosis of 3.7 weeks, and a wrong initial diagnosis in 7 patients. Most frequent symptoms were the refusal to sit (70%) and an alteration in gait or refusal to walk (50%), with pain at spinal palpation (80%), and stiffness (70%). All patients had unspecific laboratory test anomalies, and radiographs were normal in 6 patients. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on 9 patients and was diagnostic in all of them. All patients were treated and remained asymptomatic after a mean follow-up of 24.2 months, but radiographic abnormalities persist in 80% of them.

DiscussionThe diagnosis of discitis is difficult in patients under 3 years due to the absence of specific clinical and laboratory findings. Magnetic resonance is the tool of choice to make the diagnosis. Treatment consists of a combination of antibiotics and orthosis. Radiological abnormalities persist in the majority of cases.

ConclusionsIn patients under 3 years with the suspected diagnosis of discitis, MRI should be considered in the diagnosis of discitis. Symptoms resolve with antibiotics and immobilization. Because of the persistency of the radiographical abnormalities, a long-term period of follow-up is advised to detect long-term sequelae.

Revisar los casos de discitis tratados en nuestra unidad en menores de 3 años.

Material y métodoAnálisis retrospectivo de los 10 casos de discitis en niños hospitalizados desde enero de 1998 a diciembre de 2010.

ResultadosEl nivel más afectado fue L5-S1 (4 casos), seguido de L4-L5 (3 casos). El motivo de consulta fue inespecífico, lo que llevó a un retraso en el diagnóstico de 3,7 semanas y un diagnóstico inicial erróneo en 7 casos. Los síntomas más frecuentes fueron rechazo a la sedestación (70%) y alteración o rechazo a la marcha (50%), con dolor a la palpación (80%) y rigidez en la zona afecta (70%). Todos los pacientes presentaron alteraciones analíticas inespecíficas y la radiología simple fue negativa en 6 casos. En 9 pacientes se les realizó una resonancia nuclear magnética (RNM) diagnóstica. Tras el tratamiento y un seguimiento medio de 24,2 meses todos los pacientes permanecen asintomáticos pero con secuelas radiológicas en el 80%.

DiscusiónLas discitis en niños menores de 3 años son difíciles de diagnosticar por la inespecificidad de la clínica y de los datos analíticos. La RNM es la prueba diagnóstica más concluyente. El tratamiento consiste en antibióticos e inmovilización con corsé, persistiendo alteraciones radiológicas durante años.

ConclusionesAnte un paciente menor de 3 años y la sospecha de discitis, se debería valorar realizar una RNM. Los pacientes evolucionan bien con tratamiento antibiótico e inmovilización, pero se debe de realizar seguimiento durante años para detectar posibles secuelas a medio o largo plazo.

Discitis or spondylodiscitis is very rare in pediatric age.1–9 There is a peak incidence in children under 3 years old and a second, smaller peak in early adolescence.3,8,9 The etiology of discitis is controversial and several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the origin or cause of this disease, including a possible infectious, traumatic or idiopathic inflammation etiology.1–3,7,8,10,11

One of the main problems in discitis is diagnostic delay1,8,12 due to unspecific symptoms and the fact that alterations in plain radiographs take between 2 and 3 weeks to become detectable.2,7,13,14 Discitis in children under 3 years is most difficult to diagnose because, in addition to the aforementioned characteristics, it is difficult to obtain a thorough clinical history, and children in this age range do not cooperate during a physical examination.8 For this reason, several authors argue that, in cases with high clinical suspicion with a compatible simple radiographic study (simple radiography with anteroposterior and lateral projections of the suspected area) and without pathological findings, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan should be obtained urgently so as not to delay the start of treatment.4,7,8,12,15 Laboratory tests are not reliable for diagnostic purposes, since in many cases the parameters are normal or only slightly elevated (blood leukocytes, C-reactive protein [CRP] and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]),1,5 and blood cultures or cultures of the biopsy material are also negative in many cases (56–100% depending on the series).1,2,4,8,12

Once the diagnosis of discitis has been established, treatment should be started early, including rest, immobilization with a brace (or orthesis) and antibiotic therapy.2,11,14 Some authors suggest that surgery may be indicated, albeit in very advanced and carefully selected cases.2,14,16

The aim of this study was to retrospectively review cases of discitis treated at our unit over a period of 13 years in children aged under 3 years, with the objective of clarifying the diagnosis and improving the management of these patients.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a retrospective review of cases of discitis in children under 3 years of age treated during the period between January 1998 and December 2010 at the orthopedic and pediatric traumatology unit of our tertiary hospital. A total of 10 cases of discitis were attended during this period of 13 years.

The data analyzed were obtained from the medical records of patients. We collected epidemiological data, reason for consultation, symptoms presented by patients, diagnostic delay from the onset of symptoms, misdiagnosis before establishing the diagnosis of discitis, analytical studies including number of leukocytes, CRP and ESR, treatment followed in each case and data on both clinical evolution and radiographic evolution. Imaging tests, both plain radiographs and MRI, both at the time of diagnosis and during evolution controls, were reviewed with the software package used at our hospital (IMPAX® v.6.4.0.4551; Agfa Healthcare Corporation, Greenville, SC, USA).

We calculated the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) from the results obtained for each parameter analyzed. For non-numerical data we calculated the percentage of patients presenting each characteristic.

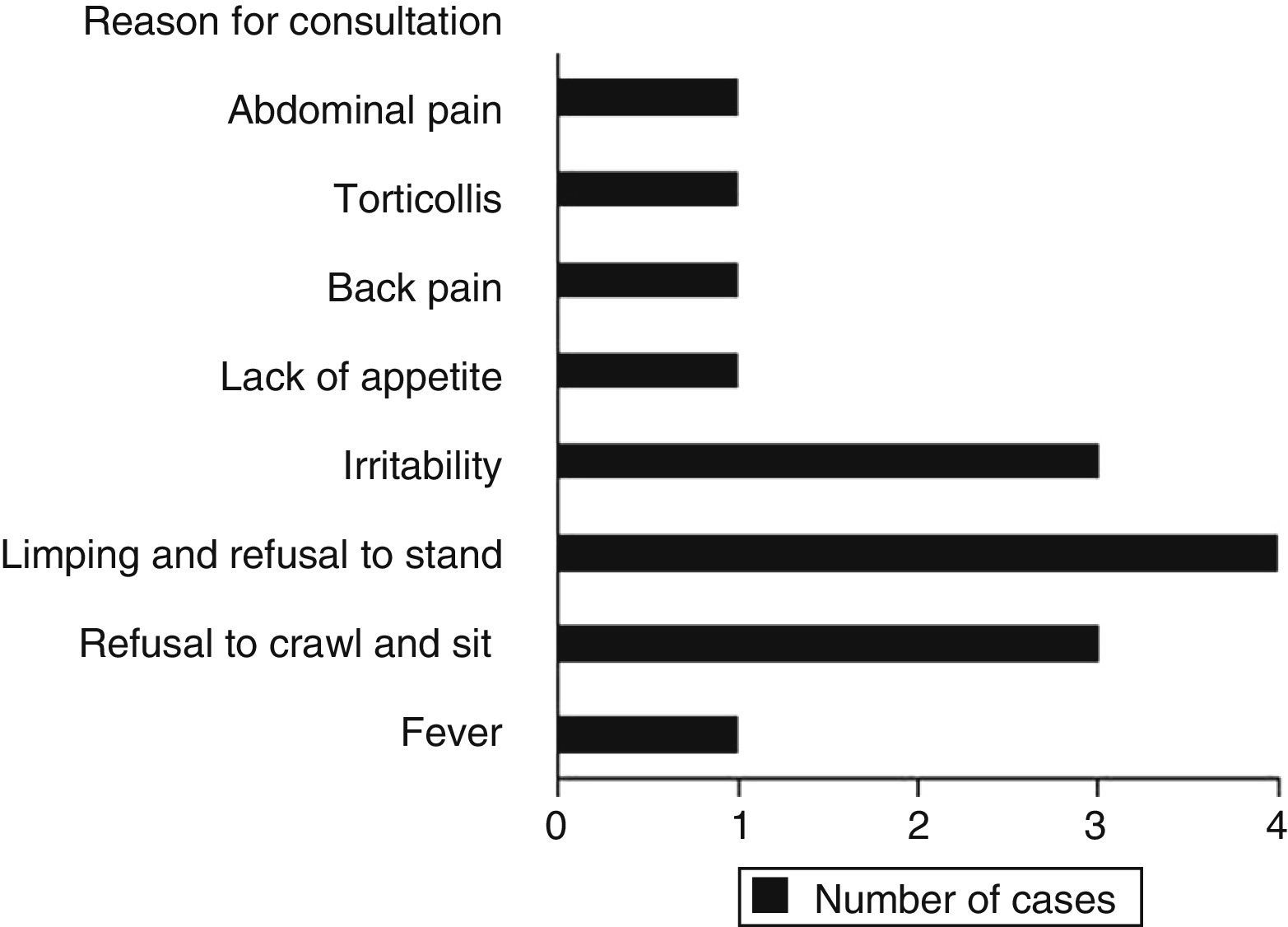

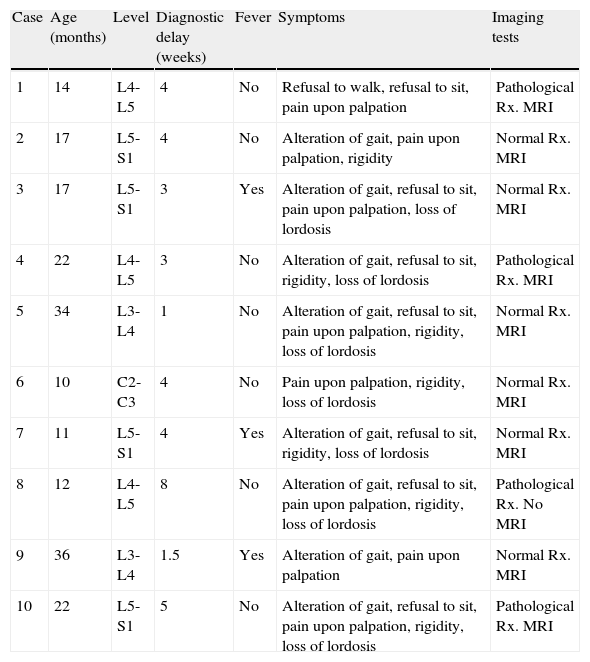

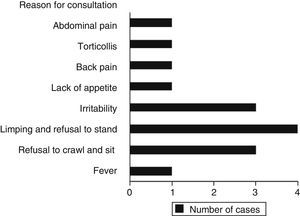

ResultsWe recorded 10 cases of discitis during the 13-year period studied (Table 1), including 7 boys and 3 girls, with a mean age of 19.5±2.9 months (range: 10–36 months). The most frequently affected level was L5-S1 (4 cases), followed by L4-L5 (3 cases), L3-L4 (2 cases) and 1 case in the cervical region (C2-C3). The reasons for consultation were nonspecific (Fig. 1), thus leading to a mean diagnostic delay of 3.7±0.6 weeks (range: 1–8 weeks). The most common symptom was refusal to sit (70%), followed by alteration or refusal to walk (50%). During the physical examination, 80% of patients presented tenderness on palpation and 70% presented rigidity in the affected area. Only 3 patients suffered fever (temperature over 37.5°C). In 7 cases, the initial diagnosis was erroneous, with the most frequent being synovitis of the hip (4 cases), followed by septic hip arthritis, muscle contracture and eosinophilic granuloma. In the remaining 3 cases the first diagnosis reflected in the medical record was discitis.

Data of clinical cases.

| Case | Age (months) | Level | Diagnostic delay (weeks) | Fever | Symptoms | Imaging tests |

| 1 | 14 | L4-L5 | 4 | No | Refusal to walk, refusal to sit, pain upon palpation | Pathological Rx. MRI |

| 2 | 17 | L5-S1 | 4 | No | Alteration of gait, pain upon palpation, rigidity | Normal Rx. MRI |

| 3 | 17 | L5-S1 | 3 | Yes | Alteration of gait, refusal to sit, pain upon palpation, loss of lordosis | Normal Rx. MRI |

| 4 | 22 | L4-L5 | 3 | No | Alteration of gait, refusal to sit, rigidity, loss of lordosis | Pathological Rx. MRI |

| 5 | 34 | L3-L4 | 1 | No | Alteration of gait, refusal to sit, pain upon palpation, rigidity, loss of lordosis | Normal Rx. MRI |

| 6 | 10 | C2-C3 | 4 | No | Pain upon palpation, rigidity, loss of lordosis | Normal Rx. MRI |

| 7 | 11 | L5-S1 | 4 | Yes | Alteration of gait, refusal to sit, rigidity, loss of lordosis | Normal Rx. MRI |

| 8 | 12 | L4-L5 | 8 | No | Alteration of gait, refusal to sit, pain upon palpation, rigidity, loss of lordosis | Pathological Rx. No MRI |

| 9 | 36 | L3-L4 | 1.5 | Yes | Alteration of gait, pain upon palpation | Normal Rx. MRI |

| 10 | 22 | L5-S1 | 5 | No | Alteration of gait, refusal to sit, pain upon palpation, rigidity, loss of lordosis | Pathological Rx. MRI |

| Case | Leukocytes (×103/μl | ESR (mm/h) | CRP (mg/l) | Orthesis (months) | IV ATB (days) | O ATB (weeks) | Follow-up (months) | Radiographic sequelae |

| 1 | 12.3 | 59 | 3.2 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 26 | Yes |

| 2 | 11.2 | 46 | 94 | 3.5 | 8 | 6 | 24 | Yes |

| 3 | 13.2 | 52 | 27 | 5 | 27 | 10 | 27 | Yes |

| 4 | 13.4 | 39 | 9 | 12 | 16 | 10 | 12 | Yes |

| 5 | 7.6 | 44 | 13 | 2.5 | 0 | 6 | 12 | Yes |

| 6 | 10.7 | 40 | 27 | 4 | 14 | 12 | 12 | No |

| 7 | 19.3 | 60 | 14 | 6 | 15 | 20 | 16 | No |

| 8 | 12.8 | 46 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 7.5 | 89 | Yes |

| 9 | 5.2 | 76 | 23 | 3 | 21 | 8 | 12 | Yes |

| 10 | 13.5 | 75 | 26 | 4 | 15 | 14 | 12 | Yes |

ATB: antibiotic therapy; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IV: intravenous; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging (it was diagnostic in all cases in which it was performed); O: oral; Rx: initial simple radiograph.

We found analytical alterations in all patients, including blood leukocyte count of 11.9±1.2×103/μl (range: 5.2–19.3×103leukocytes/μl), with leukocytosis being present in 80% of patients, elevated ESR in all patients, with a mean value of 53.7±4.3mm/h (range: 39–76mm/h) and elevated CRP levels in 80% of patients, with a mean value of 23.6±8.4mg/l (range: 0–94mg/l).

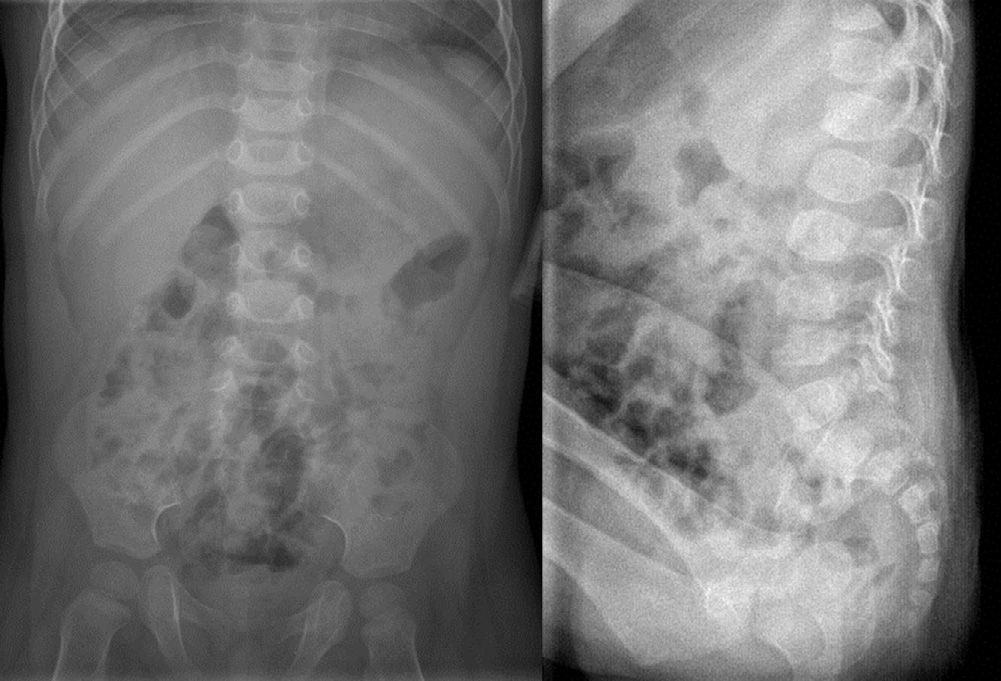

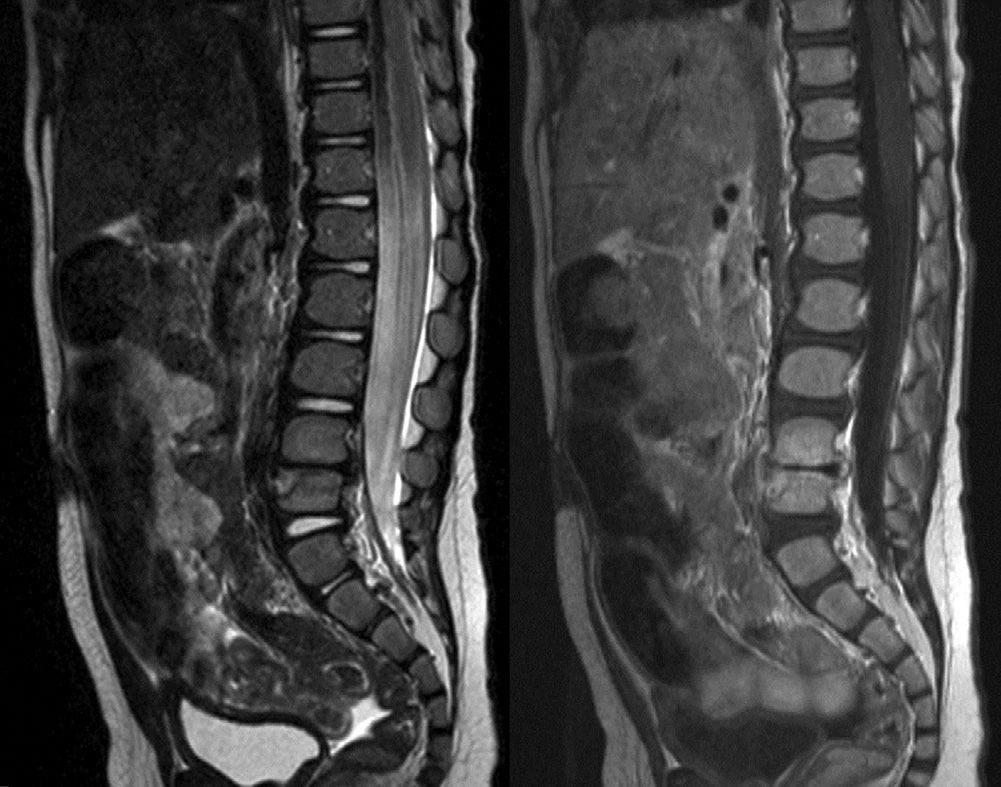

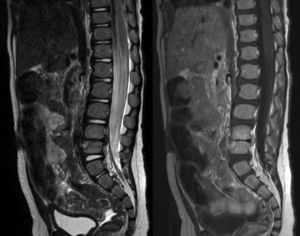

All patients underwent an initial radiographic study (plain radiographs of the affected area in anteroposterior and lateral projections) (Fig. 2) which was negative in 60% of cases. A total of 9 patients underwent an MRI scan (Fig. 3) which had diagnostic value in all cases (in 1 case we considered that the plain radiographic image along with the symptoms were sufficient to establish a diagnosis of discitis), and which identified a paravertebral abscess in 6 cases.

T1 (right) and T2 (left) MRI sections of a 14-month-old patient suffering L4-L5 discitis (same patient as in Fig. 2).

Treatment consisted of antibiotic therapy during 11.0±1.4 weeks (range: 6–20 weeks) administered intravenously over 13.6±2.5 days (range: 0–27 days) followed by (and in some cases overlapping with) oral antibiotics for 10.2±1.4 weeks (range: 6–20 weeks), and immobilization using a brace for 5.3±0.9 months (range: 3–12 months). Clinical improvement and laboratory improvement were achieved after 8.0±1.8 days (range: 3–23 days) and 6.9±1.3 days (range: 3–16 days), respectively.

All the patients remain asymptomatic after a mean follow-up period of 24.2±7.5 months (range: 12–89 months). However, 80% of patients presented residual radiographic abnormalities (sclerosis and irregularity of the vertebral endplates, osteophytes in the vertebral bodies and reduction of the intervertebral space) (Fig. 4).

Plain radiographs, in the anteroposterior and lateral projections, of a patient suffering L4-L5 discitis, obtained at 26 months after diagnosis, at an age of 3 years and 4 months (same patient as in Figs. 2 and 3). A decrease in the intervertebral space can be observed, as well as sclerosis of the upper and lower vertebral plates.

Despite there being a peak incidence at the age of 3 years, discitis in children younger than that age remains a rare disease, with insidious presentation, nonspecific symptoms and inconclusive results in laboratory tests. It may also go unnoticed on plain radiographs until after a few weeks evolution. All these factors may lead to a delay in diagnosis.

We present a series of 10 cases of discitis during the 13 years reviewed. In order to achieve greater homogeneity among the cases, we have only included in this study cases of discitis in children aged under 3 years. There are few published series (Tables 2 and 3) and even less if we differentiate by age.4,7,8 Although the number of cases in our series may seem small initially, it is comparable to that in other studies. For example, when considering only children under 3 years, the series by Spencer and Wilson reported 8 cases over a period of 18 years,1 the series by Kayser et al. reported 10 cases over a period of 20 years,5 and the series by Fernandez et al. reported 29 cases over a period of 19 years.9 Although the mean age of our patients was lower than that published by other authors,1,3,5,6,9,10,12 it was comparable to those series comprising cases under the age of 3 years.1,4,7,8 The most frequent location in all the series reviewed was the lumbar region (Table 2), although the most frequent level varied from one series to another. As in other series,6,12 the most affected level in our series was the L5-S1, although other studies have reported the L3-L4 as the most affected level.1,3,7,8,11

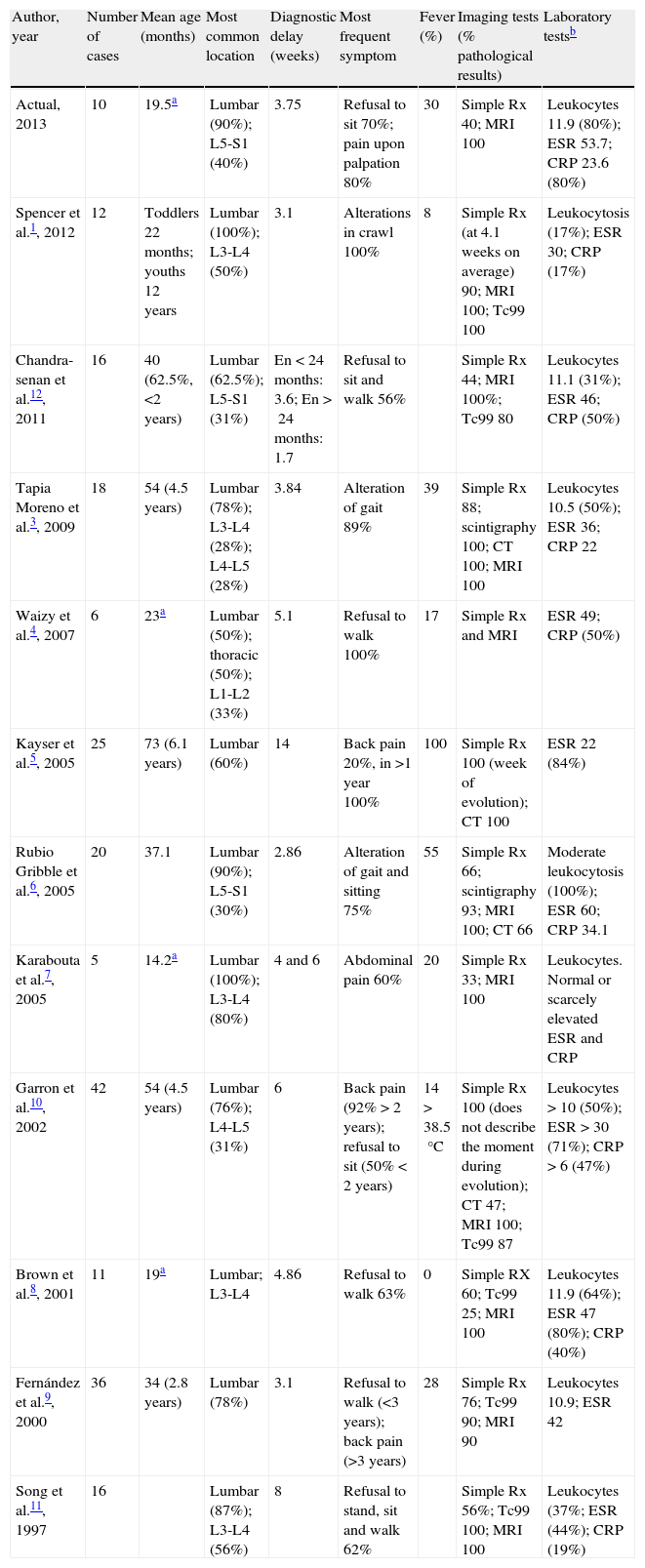

Series of discitis cases 1997–2013. Diagnosis.

| Author, year | Number of cases | Mean age (months) | Most common location | Diagnostic delay (weeks) | Most frequent symptom | Fever (%) | Imaging tests (% pathological results) | Laboratory testsb |

| Actual, 2013 | 10 | 19.5a | Lumbar (90%); L5-S1 (40%) | 3.75 | Refusal to sit 70%; pain upon palpation 80% | 30 | Simple Rx 40; MRI 100 | Leukocytes 11.9 (80%); ESR 53.7; CRP 23.6 (80%) |

| Spencer et al.1, 2012 | 12 | Toddlers 22 months; youths 12 years | Lumbar (100%); L3-L4 (50%) | 3.1 | Alterations in crawl 100% | 8 | Simple Rx (at 4.1 weeks on average) 90; MRI 100; Tc99 100 | Leukocytosis (17%); ESR 30; CRP (17%) |

| Chandra-senan et al.12, 2011 | 16 | 40 (62.5%, <2 years) | Lumbar (62.5%); L5-S1 (31%) | En<24 months: 3.6; En>24 months: 1.7 | Refusal to sit and walk 56% | Simple Rx 44; MRI 100%; Tc99 80 | Leukocytes 11.1 (31%); ESR 46; CRP (50%) | |

| Tapia Moreno et al.3, 2009 | 18 | 54 (4.5 years) | Lumbar (78%); L3-L4 (28%); L4-L5 (28%) | 3.84 | Alteration of gait 89% | 39 | Simple Rx 88; scintigraphy 100; CT 100; MRI 100 | Leukocytes 10.5 (50%); ESR 36; CRP 22 |

| Waizy et al.4, 2007 | 6 | 23a | Lumbar (50%); thoracic (50%); L1-L2 (33%) | 5.1 | Refusal to walk 100% | 17 | Simple Rx and MRI | ESR 49; CRP (50%) |

| Kayser et al.5, 2005 | 25 | 73 (6.1 years) | Lumbar (60%) | 14 | Back pain 20%, in >1 year 100% | 100 | Simple Rx 100 (week of evolution); CT 100 | ESR 22 (84%) |

| Rubio Gribble et al.6, 2005 | 20 | 37.1 | Lumbar (90%); L5-S1 (30%) | 2.86 | Alteration of gait and sitting 75% | 55 | Simple Rx 66; scintigraphy 93; MRI 100; CT 66 | Moderate leukocytosis (100%); ESR 60; CRP 34.1 |

| Karabouta et al.7, 2005 | 5 | 14.2a | Lumbar (100%); L3-L4 (80%) | 4 and 6 | Abdominal pain 60% | 20 | Simple Rx 33; MRI 100 | Leukocytes. Normal or scarcely elevated ESR and CRP |

| Garron et al.10, 2002 | 42 | 54 (4.5 years) | Lumbar (76%); L4-L5 (31%) | 6 | Back pain (92%>2 years); refusal to sit (50%<2 years) | 14>38.5°C | Simple Rx 100 (does not describe the moment during evolution); CT 47; MRI 100; Tc99 87 | Leukocytes>10 (50%); ESR>30 (71%); CRP>6 (47%) |

| Brown et al.8, 2001 | 11 | 19a | Lumbar; L3-L4 | 4.86 | Refusal to walk 63% | 0 | Simple RX 60; Tc99 25; MRI 100 | Leukocytes 11.9 (64%); ESR 47 (80%); CRP (40%) |

| Fernández et al.9, 2000 | 36 | 34 (2.8 years) | Lumbar (78%) | 3.1 | Refusal to walk (<3 years); back pain (>3 years) | 28 | Simple Rx 76; Tc99 90; MRI 90 | Leukocytes 10.9; ESR 42 |

| Song et al.11, 1997 | 16 | Lumbar (87%); L3-L4 (56%) | 8 | Refusal to stand, sit and walk 62% | Simple Rx 56%; Tc99 100; MRI 100 | Leukocytes (37%; ESR (44%); CRP (19%) |

CRP: C-reactive protein; CT: computed tomography; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging (it was diagnostic in all cases in which it was performed); simple Rx: simple radiograph; Tc99: computed tomography with technetium 99m.

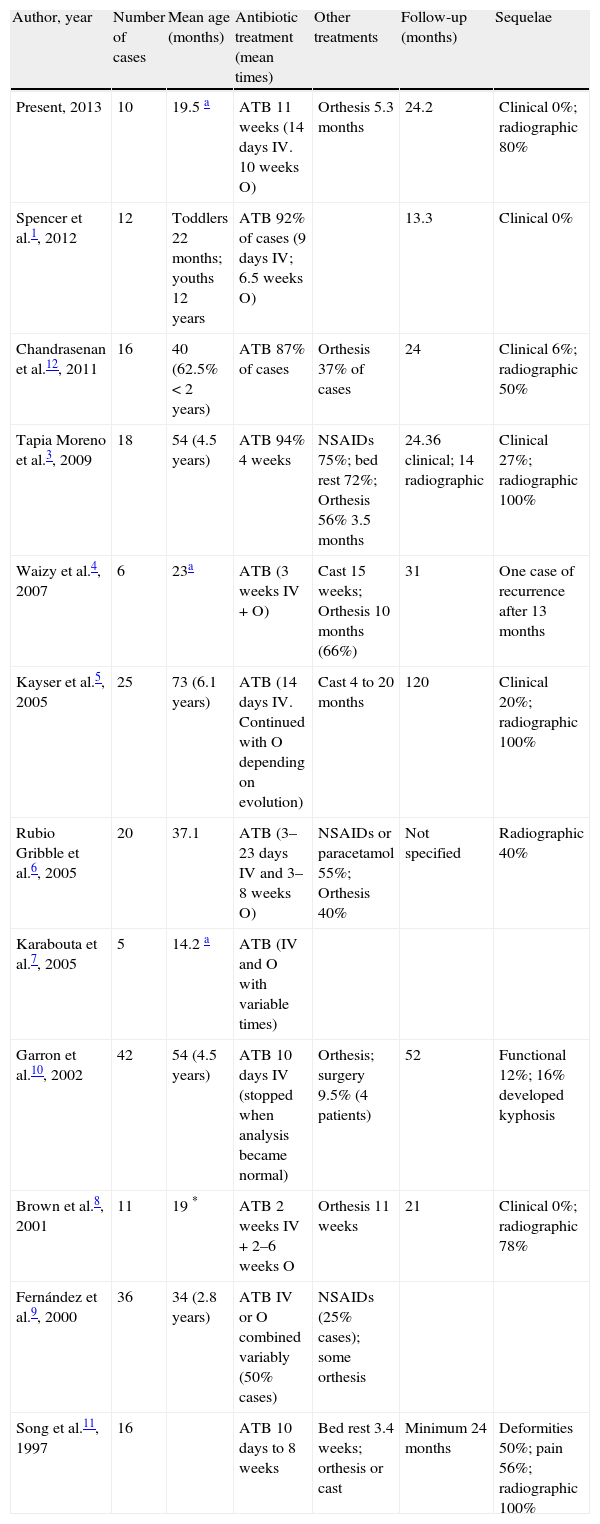

Series of cases of discitis 1997–2013. Treatment, follow-up and sequelae.

| Author, year | Number of cases | Mean age (months) | Antibiotic treatment (mean times) | Other treatments | Follow-up (months) | Sequelae |

| Present, 2013 | 10 | 19.5 a | ATB 11 weeks (14 days IV. 10 weeks O) | Orthesis 5.3 months | 24.2 | Clinical 0%; radiographic 80% |

| Spencer et al.1, 2012 | 12 | Toddlers 22 months; youths 12 years | ATB 92% of cases (9 days IV; 6.5 weeks O) | 13.3 | Clinical 0% | |

| Chandrasenan et al.12, 2011 | 16 | 40 (62.5%<2 years) | ATB 87% of cases | Orthesis 37% of cases | 24 | Clinical 6%; radiographic 50% |

| Tapia Moreno et al.3, 2009 | 18 | 54 (4.5 years) | ATB 94% 4 weeks | NSAIDs 75%; bed rest 72%; Orthesis 56% 3.5 months | 24.36 clinical; 14 radiographic | Clinical 27%; radiographic 100% |

| Waizy et al.4, 2007 | 6 | 23a | ATB (3 weeks IV+O) | Cast 15 weeks; Orthesis 10 months (66%) | 31 | One case of recurrence after 13 months |

| Kayser et al.5, 2005 | 25 | 73 (6.1 years) | ATB (14 days IV. Continued with O depending on evolution) | Cast 4 to 20 months | 120 | Clinical 20%; radiographic 100% |

| Rubio Gribble et al.6, 2005 | 20 | 37.1 | ATB (3–23 days IV and 3–8 weeks O) | NSAIDs or paracetamol 55%; Orthesis 40% | Not specified | Radiographic 40% |

| Karabouta et al.7, 2005 | 5 | 14.2 a | ATB (IV and O with variable times) | |||

| Garron et al.10, 2002 | 42 | 54 (4.5 years) | ATB 10 days IV (stopped when analysis became normal) | Orthesis; surgery 9.5% (4 patients) | 52 | Functional 12%; 16% developed kyphosis |

| Brown et al.8, 2001 | 11 | 19 * | ATB 2 weeks IV+2–6 weeks O | Orthesis 11 weeks | 21 | Clinical 0%; radiographic 78% |

| Fernández et al.9, 2000 | 36 | 34 (2.8 years) | ATB IV or O combined variably (50% cases) | NSAIDs (25% cases); some orthesis | ||

| Song et al.11, 1997 | 16 | ATB 10 days to 8 weeks | Bed rest 3.4 weeks; orthesis or cast | Minimum 24 months | Deformities 50%; pain 56%; radiographic 100% |

ATB: antibiotic therapy; IV: intravenous; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; O: oral.

The reasons for consultation varied significantly (Fig. 1). This fact, combined with the difficulty entailed by patients (children under 3 years) being unable to explain their problem,8 nonspecific presentation symptoms (refusal to sit or walk)3,4,6,8–12 and the inconclusive results of complementary tests, made the initial diagnosis very complicated and often erroneous (70% of patients in our series). This often led to a delay in the diagnosis of discitis, which is one of the major problems of this disease.1,8,12,17 We must always conduct an exploration of the back of patients with nonspecific symptoms because, even if the symptoms are refusal to walk or sit, or even abdominal symptoms,7 patients often present selective pain upon palpation of the affected vertebral levels (80% of our patients) or rigidity for spinal mobility.3–5,10 In our series, the delay in diagnosis was 3.7 weeks, which was within the range of delay in diagnosis of the analyzed series (2.86–14 weeks) (Table 2). It is important to eliminate the idea that the diagnosis of discitis is associated to fever (only 30% of patients in our series presented it) because, although some series have reported the presence of fever in 100% of patients,5 in most series the percentage of patients with fever is below 50%, even reaching 0% (Table 2).1,3,4,7–10

Our patients presented moderate leukocytosis in 80% of cases, slightly elevated ESR levels in all cases and a slight elevation of CRP in 80% of cases. This moderate increase in laboratory parameters was repeated in all the series studied (Table 2). However, although it may serve to monitor the response of patients to treatment, it does not allow for a definitive diagnosis or rule out a suspected diagnosis.1,2,5,14

Regarding imaging tests, discitis causes a decrease in the height of the intervertebral disk which is visible on plain radiographs at 2 or 3 weeks evolution.2,7,13,14 Therefore, plain radiography is not reliable to establish an early diagnosis (only 40% of initial plain radiographs were pathological in our series). Series presenting alterations in plain radiographs in 100% of cases are those with a longer diagnostic delay5 or those which consider simple radiography pathological, but not necessarily at the time of diagnosis.1,10,11 We have used various imaging tests in an attempt to confirm the diagnosis, but at present there seems to be unanimity regarding the fact that MRI is the imaging test of choice for the diagnosis of discitis, as it has a diagnostic rate close to 100% of cases.1,3,6–12,15 In our series, MRI was the imaging test which confirmed the diagnosis in 9 of the 10 cases (plain radiographs were normal in 6 of these 9 cases, whilst in 3 cases they were pathological but it was considered that an MRI scan was required to confirm the diagnosis). Only in 1 of the 10 cases was the initial pathological radiograph considered sufficient to diagnose discitis without obtaining an MRI (coinciding with the case in our series with the longest diagnostic delay: 8 weeks) (Table 1). Therefore, in our experience, MRI has been the decisive diagnostic test to establish or confirm the early diagnosis of discitis.

Although there is no unanimously established treatment protocol, most authors agree on the use of antibiotics (with different antibiotics, orally and/or intravenously, although there are differences in treatment duration),2,14 rest, use of immobilization systems (cast or orthesis), and in some cases, treatment with NSAIDs (Table 3). There is controversy regarding the etiology of discitis, with suggestions of an infectious, traumatic or idiopathic inflammation origin.1–3,7,8,10,11 Nevertheless, in our experience, evolution with antibiotic therapy has been favorable in all cases. The same authors who question an infectious etiology include antibiotics in the treatment of all or most of their patients.1–3,7,8,10,11 In our center, after assessing the evolution of the different cases, we have established treatment with an intravenous, broad-spectrum antibiotic (amoxicillin-clavulanate in most cases) for at least 7 days or until the analytical parameters have returned to normality, continued orally until at least 3 months of treatment have been completed. NSAIDs are used as symptomatic treatment according to each case. We used an orthesis for the treatment of pain and rigidity in all cases, and immobilization of vertebral spaces suffering an infectious and/or inflammatory process, for at least 3 months.

Although the clinical course is usually very good, with an adequate response to treatment (in our series, clinical and analytical improvement were observed after a mean period of 8 and 6.9 days, respectively), sequelae were observed in medium and long term follow-up, with reduced rates of functional and clinical sequelae, but with significant rates of radiographic sequelae (sclerosis of the vertebral plates and reduction of the intervertebral space) (Table 3).3,5,8,11 This has led us to consider the need to extend the follow-up period of our patients.

This work presents the typical limitations of a retrospective study, in addition to being a series with a relatively small number of patients who were treated over 13 years, so there was a certain degree of heterogeneity in the diagnostic approach and the treatment employed.

In conclusion, we must remain alert in cases of patients under 3 years of age who present nonspecific symptoms, inconclusive laboratory tests and normal simple radiographs. We must obtain a full exploration of the spine in all patients who refuse to or have abnormal walking or sitting position. Given the clinical suspicion of discitis and plain radiographs without pathological findings, MRI is the test of choice for early diagnosis and should provide confirmation of the diagnosis in order to start an early treatment. The appearance of radiographic alterations in evolutionary controls at 2 years of age should lead us to consider the need for longer-term monitoring, so as to study whether these consequences are self-limiting or else progress over time, even causing problems in adulthood.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation adhered to the ethical guidelines of the Committee on Responsible Human Experimentation, as well as the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Miranda I, Salom M, Burguet S. Discitis en niños menores de 3 años. Serie de casos y revisión de la literatura. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2014;58:92–100.