To determine the cost reduction and complication rates of using an enhanced recovery pathway (Fast-track) when compared to traditional recovery in primary total hip replacement (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR), as well as to determine if there were significant differences in complication rates.

Materials and methodsRetrospective review of 100 primary total arthroplasties using the Fast-track recovery system and another 100 using conventional recovery. Gender, Charlston comorbidity index, ASA score, length of stay and early complications were measured, as well in-hospital complications and those in the first six months, re-admissions and transfusion rates. The total and daily cost of stay was determined and the cost reduction was calculated based on the reduction in the length of stay found between the groups.

ResultsBoth groups where comparable as regards age, gender, ASA score, and Charlston index. The mean reduction in length of stay was 4.5 days for TKR and 2.1 days for THR. The calculated cost reduction was 1266euros for TKR and 583euros for THR. There were no statistically significant differences between groups regarding in-hospital complications, transfusion requirements, re-admissions and complication rates in the first six months.

DiscussionThere are few publications in the literature reviewed that analyse the cost implications of using fast-track recovery protocols in arthroplasty. Several published series comparing recovery protocols found no significant differences in complication rates either. The use of a fast-track recovery protocol resulted in a significant cost reduction of 1266euros for the TKR group and 583 for the THR group, without affecting complication rates.

Determinar el ahorro económico que supone la implantación de un sistema de recuperación rápida (fast-track) al compararlo con el método de recuperación convencional en artroplastia primaria de cadera (ATC) y rodilla (ATR). Asimismo, determinar si existen diferencias entre ambos en el índice de complicaciones.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo descriptivo, incluyendo 100 artroplastias primarias utilizando el método fast-track y 100 utilizando recuperación convencional. Las variables comparadas entre ambos grupos fueron edad, sexo, índice de comorbilidad de Charlson, ASA, estancia media, complicaciones intrahospitalarias y durante los primeros seis meses e índice de reingresos y transfusiones. Se determinó el coste global para cada procedimiento y por día de ingreso, y el ahorro se calculó según la reducción de la estancia media.

ResultadosAmbos grupos fueron comparables en cuanto a edad, sexo, ASA e índice de Charlson. La reducción de la estancia media hospitalaria fue de 4,5 días para el grupo de ATR y 2,1 días para el de ATC. El ahorro calculado fue de 1.266 euros para el grupo de ATR y de 583 euros en el de ATC. No se observaron diferencias significativas en cuanto a complicaciones intrahospitalarias, necesidad de transfusiones, reingresos y complicaciones durante los primeros 6 meses.

DiscusiónExisten pocos trabajos de análisis de costos en relación con la implantación de sistemas de recuperación rápida en cirugía protésica. Diversas series publicadas tampoco observaron un mayor índice de complicaciones utilizando este método. La utilización del método fast-track representó un ahorro de 1.266 euros para el grupo de ATR y de 583 euros para el grupo de ATC sin aparente repercusión sobre el índice de complicaciones.

Over the recent years, total hip and knee replacement surgeries have become 2 of the most common procedures in orthopaedic surgery.1 In this setting, there are various measures that can optimise the perioperative processes.2 The implementation of multidisciplinary systems of rapid recovery has made it possible to reduce average hospital stay, early complications and the overall cost of these procedures, without modifying the index of risks and complications,3,4 patient satisfaction,5 or the need for rehabilitation.6 However, the current literature includes few studies that quantify the economic savings that the implantation of these systems can represent with respect to the conventional protocols.7

The objectives of this study were to determine the economic savings that the implementation of a fast-track recovery system in primary total hip and knee replacement surgery represented, and to analyse the differences in the index of complications when comparing it to a conventional postoperative system.

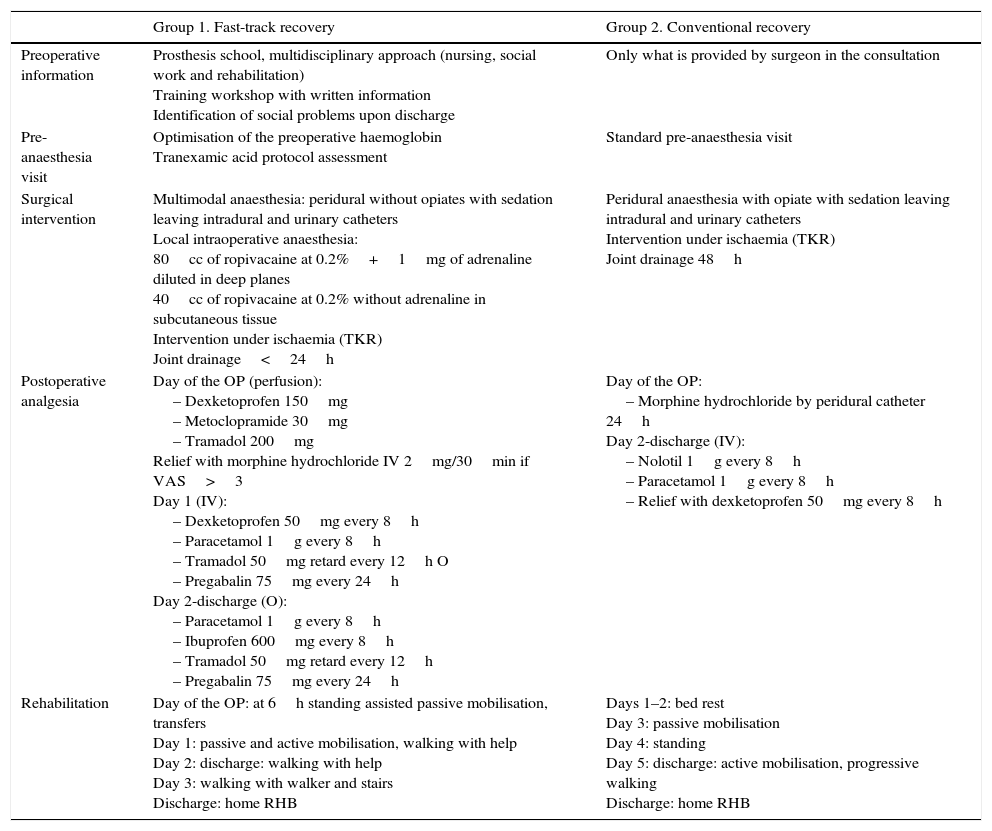

Materials and methodA retrospective study including a total 200 patients was carried out. Fifty patients that had total knee replacement (TKR) and 50 patients that had total hip replacement (THR) using the conventional recovery system were randomly chosen during the January–December 2013 period (control group). In the fast-track recovery group (case group), the first 50 patients that had TKR and the first 50 that had THR since the protocol was implanted in our centre in January 2014. The characteristics and the main differences between both recovery are shown in Table 1.

Differences between the recovery protocols.

| Group 1. Fast-track recovery | Group 2. Conventional recovery | |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative information | Prosthesis school, multidisciplinary approach (nursing, social work and rehabilitation) Training workshop with written information Identification of social problems upon discharge | Only what is provided by surgeon in the consultation |

| Pre-anaesthesia visit | Optimisation of the preoperative haemoglobin Tranexamic acid protocol assessment | Standard pre-anaesthesia visit |

| Surgical intervention | Multimodal anaesthesia: peridural without opiates with sedation leaving intradural and urinary catheters Local intraoperative anaesthesia: 80cc of ropivacaine at 0.2%+1mg of adrenaline diluted in deep planes 40cc of ropivacaine at 0.2% without adrenaline in subcutaneous tissue Intervention under ischaemia (TKR) Joint drainage<24h | Peridural anaesthesia with opiate with sedation leaving intradural and urinary catheters Intervention under ischaemia (TKR) Joint drainage 48h |

| Postoperative analgesia | Day of the OP (perfusion): – Dexketoprofen 150mg – Metoclopramide 30mg – Tramadol 200mg Relief with morphine hydrochloride IV 2mg/30min if VAS>3 Day 1 (IV): – Dexketoprofen 50mg every 8h – Paracetamol 1g every 8h – Tramadol 50mg retard every 12h O – Pregabalin 75mg every 24h Day 2-discharge (O): – Paracetamol 1g every 8h – Ibuprofen 600mg every 8h – Tramadol 50mg retard every 12h – Pregabalin 75mg every 24h | Day of the OP: – Morphine hydrochloride by peridural catheter 24h Day 2-discharge (IV): – Nolotil 1g every 8h – Paracetamol 1g every 8h – Relief with dexketoprofen 50mg every 8h |

| Rehabilitation | Day of the OP: at 6h standing assisted passive mobilisation, transfers Day 1: passive and active mobilisation, walking with help Day 2: discharge: walking with help Day 3: walking with walker and stairs Discharge: home RHB | Days 1–2: bed rest Day 3: passive mobilisation Day 4: standing Day 5: discharge: active mobilisation, progressive walking Discharge: home RHB |

TKR, total knee replacement; VAS, visual analogue scale; OP, operative procedure; IV, intravenous; RHB, rehabilitation; O, oral.

To establish sample homogeneity, the variables recorded for both groups were age, sex, Charlston comorbidity index and the ASA score. To evaluate the differences obtained between the 2 recovery protocols, the variables recorded were mean stay, index of in-hospital complications, index of readmissions, need for transfusions and complications during the first 6 months.

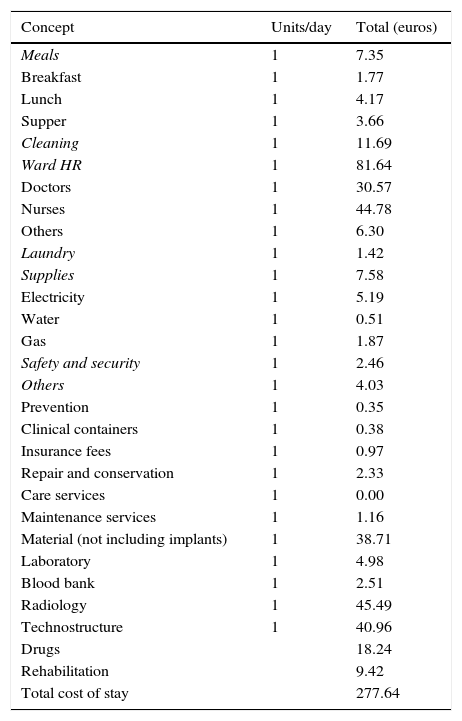

The financial department at the centre where the study was performed calculated the costs based on invoice data and establish the cost per day of admission for primary knee and hip arthroplasty processes. These figures covered the items included in Table 2.

Calculation of costs per day of admission in primary knee arthroplasty.

| Concept | Units/day | Total (euros) |

|---|---|---|

| Meals | 1 | 7.35 |

| Breakfast | 1 | 1.77 |

| Lunch | 1 | 4.17 |

| Supper | 1 | 3.66 |

| Cleaning | 1 | 11.69 |

| Ward HR | 1 | 81.64 |

| Doctors | 1 | 30.57 |

| Nurses | 1 | 44.78 |

| Others | 1 | 6.30 |

| Laundry | 1 | 1.42 |

| Supplies | 1 | 7.58 |

| Electricity | 1 | 5.19 |

| Water | 1 | 0.51 |

| Gas | 1 | 1.87 |

| Safety and security | 1 | 2.46 |

| Others | 1 | 4.03 |

| Prevention | 1 | 0.35 |

| Clinical containers | 1 | 0.38 |

| Insurance fees | 1 | 0.97 |

| Repair and conservation | 1 | 2.33 |

| Care services | 1 | 0.00 |

| Maintenance services | 1 | 1.16 |

| Material (not including implants) | 1 | 38.71 |

| Laboratory | 1 | 4.98 |

| Blood bank | 1 | 2.51 |

| Radiology | 1 | 45.49 |

| Technostructure | 1 | 40.96 |

| Drugs | 18.24 | |

| Rehabilitation | 9.42 | |

| Total cost of stay | 277.64 |

We excluded the direct costs derived from the implants due to the diversity of models and prices between the 2 periods. The nursing, social work and rehabilitation activities, including the prosthesis school, were carried out by means of staff reassignment, without causing expenses from new hires. Consequently, they were not considered when calculating the savings.

The savings calculation was later determined multiplying the total cost calculated for 1 day by the reduction of the mean stay in days found between the 2 groups.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses on all the data were carried out with SPSS v. 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For the study of continuous variables, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used, using the Mann–Whitney test when their distribution was abnormal. For the categorical variables, χ2 tests were used. The level of significance was P=.05.

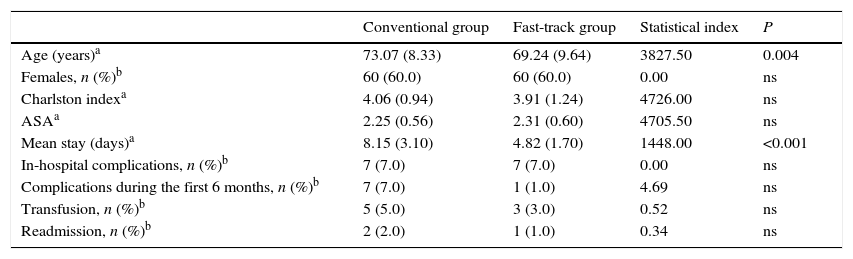

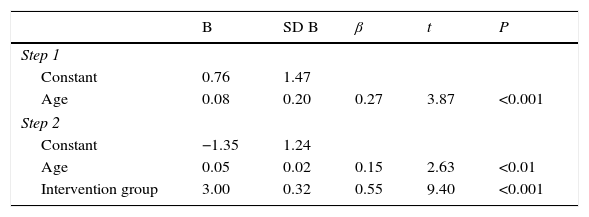

ResultsBoth groups were comparable with respect to sex, ASA and Charlson comorbidity index. However, differences were observed in age, which was greater in the conventional treatment group, with a mean age difference between the groups of 3.83 years. In light of this unexpected finding, the possible influence of age on the mean stay was analysed using a Spearman correlation; the result of this analysis showed that the mean stay was less in the fast-track group and that it was positively correlated with age (Spearman r=0.29, P<001) (Table 3). To determine the effect of the treatment on the mean stay, independently of the effect of age, a hierarchical linear regression was performed with age and treatment group as predictive variables; previously, a participant with an extreme value in the mean stay variable (mean stay=24 days, 5.84 standard deviations above the mean) had been excluded; in this way, the conditions of application of the analysis were fulfilled. In a first step, only age was included in the model; this first model explained 7% of the variation in the mean stay (Table 4). The second model included in addition the intervention group; this model explained 36% of the variation in the mean stay, with the contribution of the intervention group variable being considerably greater than the contribution of the age variable (both were statistically significant). Consequently, it was demonstrated that the reduction of the mean stay by the fast-track intervention occurred beyond the influence of patient age.

Comparison of demographic and follow-up variables.

| Conventional group | Fast-track group | Statistical index | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 73.07 (8.33) | 69.24 (9.64) | 3827.50 | 0.004 |

| Females, n (%)b | 60 (60.0) | 60 (60.0) | 0.00 | ns |

| Charlston indexa | 4.06 (0.94) | 3.91 (1.24) | 4726.00 | ns |

| ASAa | 2.25 (0.56) | 2.31 (0.60) | 4705.50 | ns |

| Mean stay (days)a | 8.15 (3.10) | 4.82 (1.70) | 1448.00 | <0.001 |

| In-hospital complications, n (%)b | 7 (7.0) | 7 (7.0) | 0.00 | ns |

| Complications during the first 6 months, n (%)b | 7 (7.0) | 1 (1.0) | 4.69 | ns |

| Transfusion, n (%)b | 5 (5.0) | 3 (3.0) | 0.52 | ns |

| Readmission, n (%)b | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0.34 | ns |

Regression coefficients of the hierarchical linear regression model with age and intervention group as predictive variables of the mean stay.

| B | SD B | β | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||||

| Constant | 0.76 | 1.47 | |||

| Age | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 3.87 | <0.001 |

| Step 2 | |||||

| Constant | −1.35 | 1.24 | |||

| Age | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 2.63 | <0.01 |

| Intervention group | 3.00 | 0.32 | 0.55 | 9.40 | <0.001 |

R2 step 1: 07, ΔR2, step 20: 29 (P<.001).

SD, standard deviation.

The reduction of the mean hospital stay for the TKR group was 4.5 days, while that for the THR group was 2.1 days. No statistically significant differences were seen as to in-hospital complications (Table 3). In both groups, there were 2 cases of decompensation of chronic respiratory pathology, 1 case of acute renal insufficiency induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the conventional TKR recovery group and 1 case of ischaemia of the lower limb for chronic arterial insufficiency that required urgent endarterectomy in the conventional THR recovery group. No differences were found in the number of transfusions or in that of readmissions (Table 3). As for complications, in the first 6 months, no differences were found between the groups either. One case of superficial infection of the surgical wound was found in both TKR groups, as well as an aseptic loosening in the TKR fast-track group and 1 perioprosthetic infection that required a change in 2 steps in the conventional TKR group.

Analysis of costsThe cost calculated per day of admission for the arthroplasty patients was 277.64 euros. When this figure was multiplied by the reduction in the mean stay, the savings calculated for each procedure were 1266 euros for the TKR group and 581 euros for the THR group.

DiscussionThe first aspect to take into consideration is the homogeneity between the groups compared, which were comparable with respect to comorbidities and demographic characteristics except in age, where the mean difference in age between the groups was 3.83 years. We consider that although the difference was statistically significant, the linear regression established that the clinical relevance that this meant was minimum and, consequently, did not invalidate the results obtained.

The reduction of the mean stay observed in our series was 4.5 days for the TKR group and 2.1 days for the THR group. Khan et al., 3 in a group of 6000 patients including both TKR and THR, obtained a reduction of 3 days in the mean stay (from 6 to 3) when a fast-track protocol was implanted. Other series that included TKR and THR, such as those of McDonald et al.8 in a group of 1816 patients or Stambough et al.9 in a group of 1751, observed reductions of 2 and 3 days, respectively. Consequently, the mean stay reduction observed in our series was similar to the rest of the series published.

With respect to the incidence of postoperative complications during the first 6 months, we did not see any differences between the 2 groups. Various published series analysed the complications, both early and delayed, comparing both protocols, without observing differences.3,5–8 Khan et al.3 did not find differences in their series as far as complications such as cerebrovascular accident, deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia, digestive haemorrhage or pulmonary thromboembolism; however, they did observe a significant reduction in the incidence of myocardial infarct in the fast-track recovery group.

In our series, there were no differences with respect to transfusion requirements. In their series, Smitha et al.6 and McDonald et al.8 observed a drop in the index of transfusions in the fast-track group. A possible cause of this difference was the greater number of patients included in these series.

Evaluating the index of readmissions and reinterventions, we did not see any differences between the 2 groups in our study. Stambough et al.,9 in a larger series, found a significant reduction in the rates of both readmissions and reinterventions for the fast-track group; this was probably due to the fact that the follow-up time in their series was 13 years.

All the patients in our study pending TKR or THR intervention were included in the fast-track protocol, independently of their anaesthesia risk or added comorbidity. In a comparative series, Dwyer et al.10 observed a reduction in the mean stay in the fast-track group and studied the relationship with the preoperative levels of haemoglobin, the ASA and body mass index (BMI). They found that for haemoglobin levels ≥14g/dl, the reduction was from 7.7 to 5.4 days (P=.02); for levels <14, it was from 7.7 to 6.2 (P=.02); in patients with ASA 1 and 2, it was from 7.6 to 5.6 days (P=.01); with ASA 3, from 8.2 to 6.4 (P=.01); in patients with BMI<30kg/m2, the reduction was from 8.1 to 6 (P=.006); and in BMI≥30kg/m2, it was from 7.5 to 5.9 (P=.0006). Consequently, it seems that all the patients can benefit from being included in the protocol, although different comorbidities can influence mean hospital stay to a greater or lesser degree.

The economic savings observed in our review was 1266 euros for the TKR group and 581 euros for the THR group. In a cost-effectiveness study of a Danish group, Larsen et al.,7 in addition to finding a significant reduction in the mean stay, established that the use of a fast-track system, in both TKR and in THR, was cost effective. Using fast-track meant a reduction of 18.850 Danish crown (US $ 4000) (95% confidence interval [CI], 1899–38.152); they also found a gain in quality-adjusted life years (QALY) of 0.08 (95% CI, 0.02–0.15) for the THR group.

Establishing the real total cost of a primary arthroplasty and the savings obtained through implementing a recovery protocol can be very complex. Diverse factors influence the calculation and it is hard to find a formula that comes as close as possible to real figures. Lavernia et al.11 analysed the relationship between funding systems and the efficacy of the fast-track recovery programmes, finding that the savings depend not only on the reduction in mean stay, but also on the charge system for processes hired by the institutions. In this study, we discovered, together with the financial and statistical departments at the centre where the study was carried out, that the greatest internal and external validity for the cost analysis would be obtaining using the figures used for invoicing; these figures are calculated based on the process and the days of admission required. In our case, the process was primary knee or hip arthroplasty; we considered that the results would be closer to the reality of our study objective if we used these figures. In spite of that, it is true that this might mean a certain bias in the results.

LimitationsFirst of all, this was a retrospective study, with the limitations characteristic of this type of reviews. Another limitation to remember is that no functional evaluation was done of the results; from this point of view, the conclusions could be obtained only from the analysis of the complications observed. Another point is that the cosy analysis did not consider more specific aspects, such as operating room costs, surgical time or small differences in drug costs. It was assumed that some of these costs modified both groups equally and, consequently, could impact the final cost of the procedure but not the savings obtained, which was the main objective of the study. Another limitation that should be considered is that the costs may be very different from other hospitals in our setting and also with respect to other countries; Consequently, the external validity of the study can be less.

ConclusionsThe implementation of a fast-track recovery system represented a significant economic savings, without apparent repercussion on the complications during the first 6 months.

We believe that it would be of great scientific and economic value to carry out comparative studies in the future between different postoperative protocols that include functional evaluations and assessment of the effect on patient quality of life and satisfaction.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments on human beings or on animals have been performed for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre about the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors wish to thank the committee for the creation and implementation of the fast-track system in prosthetic surgery of the Hospital General de Igualada, as well as the nursing and rehabilitation staff involved in it, for their intense day-to-day work to make the development and fulfilment of the protocol possible and for the excellent results achieved.

Please cite this article as: Wilches C, Sulbarán JD, Fernández JE, Gisbert JM, Bausili JM, Pelfort X. Técnica de recuperación acelerada (fast-track) aplicada a cirugía protésica primaria de rodilla y cadera. Análisis de costos y complicaciones. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:111–116.