To present a case report of bilateral posterior tarsal tunnel syndrome (PTTS) caused by an accessory flexor digitorum longus (AFDL), including the surgical technique and a review of the literature.

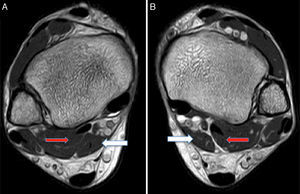

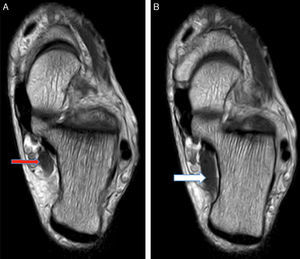

Materials and methodsTwenty-nine year old male diagnosed with bilateral PTTS, refractory to conservative management, with 53 points on the preoperative AOFAS score. MR of both ankles showed an AFDL within the tarsal tunnel, in close relationship to the posterior tibial nerve. Bilateral tarsal tunnel decompression and AFDL resection was performed.

ResultsThere were no post-operative complications. At 6 months after surgery, the patient had no pain and had 87 points on the AOFAS score.

DiscussionThe PTTS is an entrapment neuropathy of the posterior tibial nerve or one of its terminal branches. A rare cause is the presence of an AFDL, and its resection is associated with good clinical results. Careful scar tissue resection and neurolysis is recommended. Knowing the normal pathway and anatomical variability of the posterior tibial nerve and its branches is essential to avoid iatrogenic injury. In our case report, MR and intraoperative findings identified a bilateral FDLA in close relationship to the common flexor digitorum, an unusual finding, with few reports in current literature.

ConclusionsCareful tarsal tunnel decompression and AFDL resection in our patient with bilateral symptomatic PTTS has good clinical results and no complications, particularly when diagnosed and treated early.

Describir un caso de síndrome de túnel del tarso posterior (STTP) bilateral causado por un tendón flexor digitorum longus accesorio (FDLA), la técnica de resección quirúrgica y una revisión de la literatura.

Materiales y métodosReportamos el caso de un paciente varón de 29 años con diagnóstico de STTP bilateral, refractario al manejo conservador con una puntuación AOFAS de 53 puntos. Se solicitó una RM de ambos tobillos encontrándose la presencia del músculo FDLA dentro del túnel tarsiano, en íntima relación con el nervio tibial posterior. Se realiza una descompresión bilateral del túnel tarsiano resecando el músculo FDLA que producía un conflicto de espacio con el nervio tibial posterior.

ResultadosEl paciente no presentó complicaciones postoperatorias. A los 6 meses de cirugía, presentaba una puntuación final AOFAS de retropié de 87 puntos.

DiscusiónEl STTP consiste en una neuropatía por atrapamiento del nervio tibial posterior o una de sus ramas terminales. Una de sus causas es la presencia FDLA, y su resección está asociada a buenos resultados clínicos. Se recomienda la neurólisis del tejido cicatricial y adherencias alrededor del nervio. Conocer la anatomía normal y su variabilidad para liberar el nervio tibial posterior y sus ramas es fundamental para evitar lesiones iatrogénicas. En nuestro caso clínico, la RM identificó un FDLA bilateral, que al ser resecado se encontraba en íntima relación con el flexor digitorum común, hallazgo poco común en la literatura.

ConclusionesLa descompresión cuidadosa del túnel del tarso en un paciente con STTP bilateral sintomático por un FDLA se asocia a buenos resultados, particularmente en aquellos pacientes con diagnóstico y tratamiento precoz.

Nivel de evidenciaIV.

Posterior tarsal tunnel syndrome (PTTS) consists of a neuropathy due to entrapment of the posterior tibial nerve or one of its terminal branches (the medial plantar n. or the lateral plantar n.) at the level of the said tarsal tunnel. It must not be confused with anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome, which is a neuropathy due to entrapment of the deep peroneal nerve under the extensor retinaculum in the upper part of the ankle.

The first description of PTTS was by Kopell and Thompson1 in 1960, and it was subsequently ratified by Keck and Lam2 in 1962 and 1967, respectively. The tarsal tunnel is a fibre and bone structure limited by the flexor retinaculum medially and posteriorly, the tibial malleolus anteriorly and the posterior process of the astralagus and the calcaneus laterally. Havel et al.3 described the anatomical relationships of the posterior tibial nerve, which enters the channel proximally and in 93% of cases divides into three terminal branches; the medial plantar nerve, the lateral plantar nerve and the medial calcaneal nerve. The medial calcaneal nerve emerges from the posterior face of the tibial nerve in 75% of cases, and the lateral plantar nerve does so in the remaining 25% of cases. The medial calcaneal nerve terminates in 79% of cases in a single branch, and in multiple branches in 21% of cases. The calcaneal branches originate in 39% of cases proximal to the tarsal tunnel, in 34% of cases within this and in 16% of cases distal to the tunnel.3 Nevertheless, there is wide anatomical variation in the origin of the terminal branches.4 The cadaveric study of 85 origins found that the medial plantar nerve was the origin of the medial calcaneal nerve in 46% of cases; and that 37% of the specimens had a single one, 41% had two, 19% had three and 3% had four.5

It is possible to identify the cause of compression of the tibial nerve in from 60% to 80% of cases.6,7 The most common causes include ganglions, lipomas, exostosis of the tibia and calcaneus, and medial tarsal talocalcaneal coalition. A smaller percentage may be post-traumatic or idiopathic, and these cases have a poorer prognosis with surgical treatment.6 The diagnosis of PTTS is clinical. Electromyography and conduction velocity studies of the abductor digiti quinti or abductor hallucis nerves are useful diagnostic tools in the case of diagnostic doubt. Imaging studies such as ultrasound scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) make it possible to identify the cause of entrapment, and the latter is the technique of choice.8

An infrequent cause of posterior tibial nerve compression is said to be the presence of an accessory digitorum longus flexor tendon (ADLF), as a finding in MRI in asymptomatic subjects or cadaveric studies.8–16 This tendon is present in 12% of patients with PTTS.10 It corresponds to an accessory muscle that may originate in the medial edge of the tibia, the fascia of the deep posterior compartment of the leg, or from the lateral edge of the peroneus, distal to the origin of the flexor hallucis longus (FHL).12 The ADLF tendon descends posterior and superficial to the tibial nerve, passes under the flexor retinaculum through the tarsal tunnel, and is intimately connected to the tibial artery and nerve or, more frequently, with the FHL within its sheath or immediately parallel to the same.13 We report the case of a patient with a diagnosis of bilateral PTTS caused by the presence of an ADLF, identified by MRI and treated successfully with resection.

Clinical caseA male 29 year-old patient, without a history of morbidity, and who practices cycling 3 or 4 times per week. He consulted due to a two-year history of pain in the medial face of both ankles, irradiating to the posterior zone of the shin and exacerbated by exercise. He also had a sensation of paresthesia in the medial face of the ankle and bilateral plantar region. He has been treated with anti-inflammatory drugs, 40 physiotherapy sessions and three local infiltrations of corticoids.

In the physical examination he presented intense pain in the medial retromaleolar zone with a positive Tinel's sign in the tarsal tunnel of both feet, more so in the right one. He presented an AOFAS score for the back of the foot of 53 points.

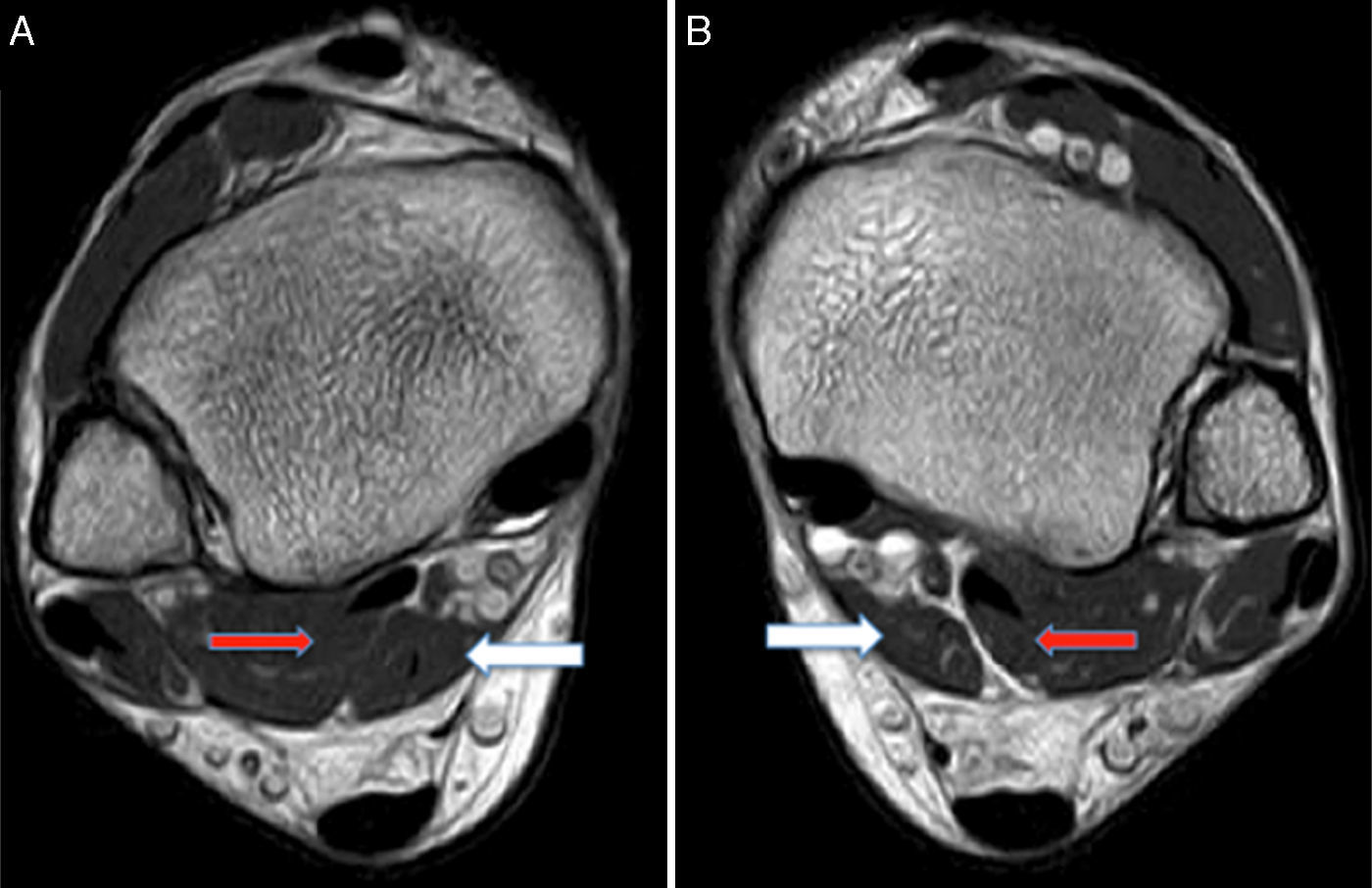

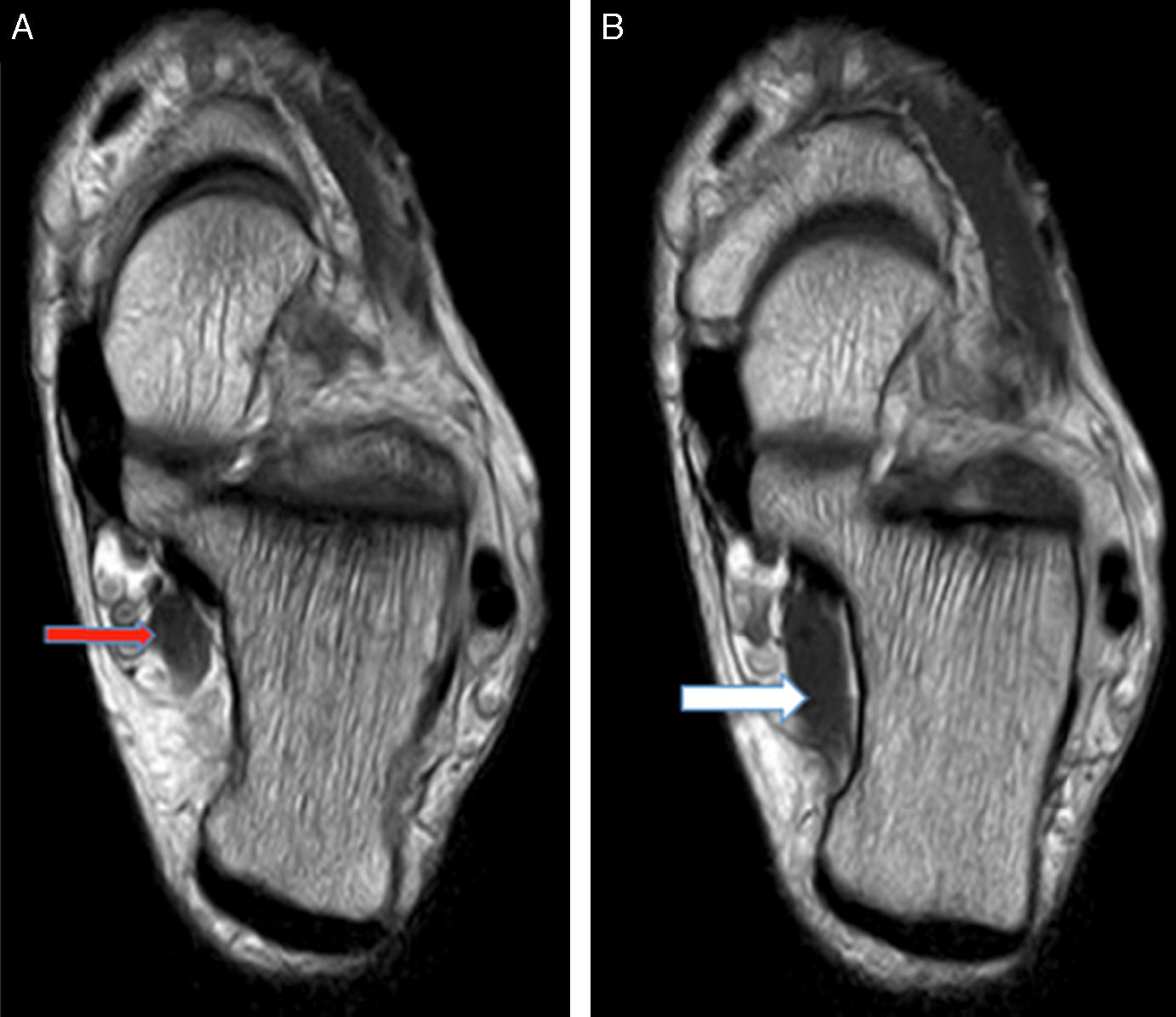

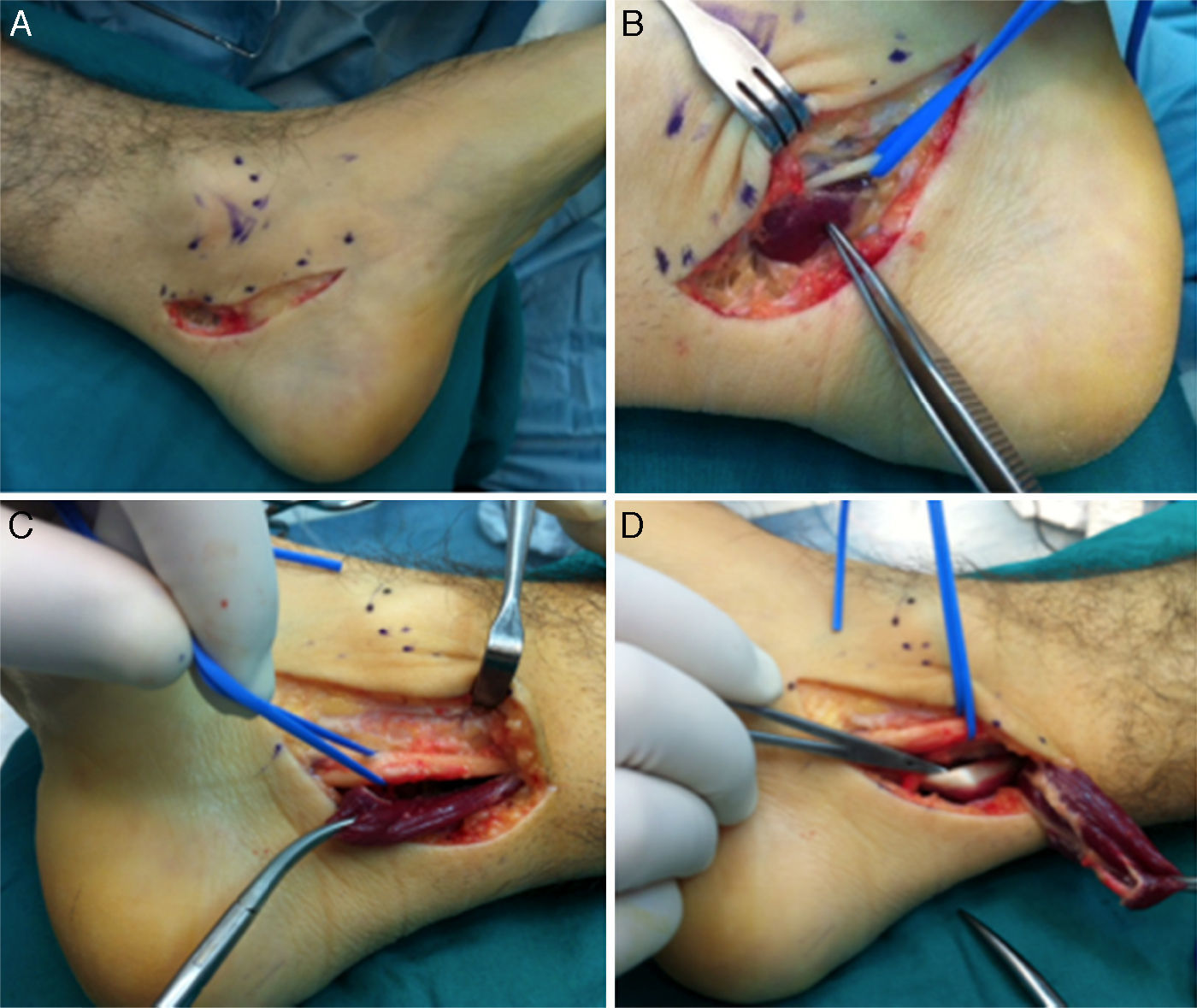

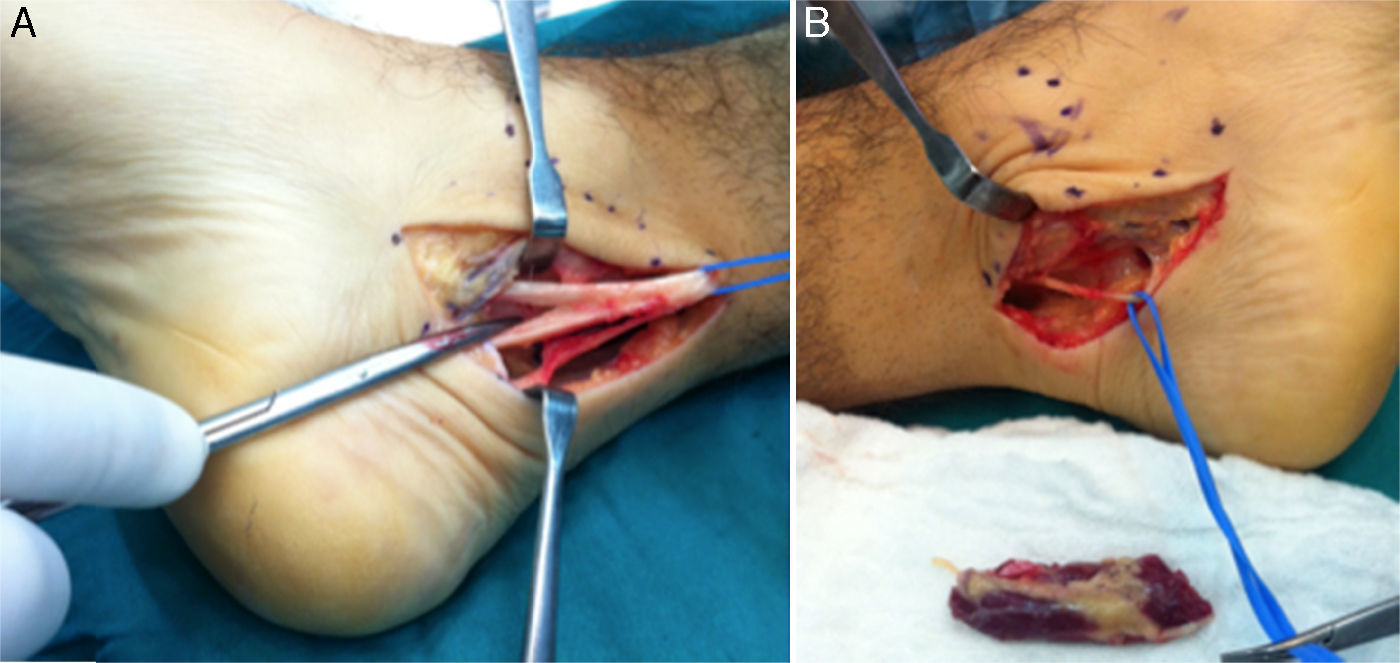

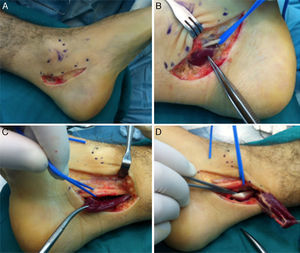

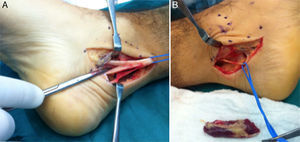

MRI was requested for both ankles, detecting the presence of an ADLF muscle within the tarsal tunnel and closely associated with the neurovascular structures (Figs. 1 and 2). The decision was taken to perform bilateral surgical decompression of the tarsal tunnel with a longitudinal approach over the tunnel until the flexor retinaculum was identified, which was then cut longitudinally. By means of careful dissection the posterior tibial nerve was identified and completely isolated (Fig. 3). The fascia of the abductor hallucis muscle was freed distally and the posterior fascia of the leg was freed proximally. In concordance with the MRI findings the ADLF muscle was identified in the tarsal tunnel, clearly competing for space with the tibial nerve. The ADLF muscle and tendon were resected. Then the distal nerve was dissected distally and the three branches of the posterior tibial nerve were identified and freed (Fig. 4). The flexor retinaculum was left open. The patient was free of discomfort soon after the operation. He used immobilising boots during three weeks, with partial load relief during four weeks. He completed ten rehabilitation sessions and returned to his sports activities after four months. At the time of the last evaluation six months after the operation he presented no signs of nerve entrapment and is free of pain and satisfied with the results. His final AOFAS score for the back of the foot is 87 points.

(A) Medial incision in the left ankle. (B) and (C) Deep dissection, isolating the lateral plantar branch of the tibial nerve and identifying the muscle portion of the ADLF in the tarsal tunnel of the left and right ankles, respectively. (D) Distal disinsertion and proximal reflection of the ADLF muscle that makes it possible to visualise the flexor digitorum comunis tendon (FDC).

PTTS is a neuropathy caused by entrapment of the posterior tibial nerve and/or any of its three main branches (the medial plantar nerve, lateral plantar nerve and medial calcaneal nerve) where it passes through the retinaculum flexor behind the medial maleolus, medial to the calcaneus. The other structures located within the tunnel are the posterior tibial artery and vein, and the posterior tibial tendons, the FDL and FHL.3

PTTS is diagnosed on the basis of its clinical symptoms, physical examination and electromyography in 90% of cases.7 Electromyography and conduction velocity studies of the abductor digiti quinti or the abductor hallucis are useful diagnostic tools in the case of diagnostic doubt.17 Nevertheless, it may be negative in post-traumatic cases, as is shown by Takakura in his series.9

Among imaging studies, ultrasound scan and MRI make it possible to look for an extrinsic cause of compression, such as soft tissue tumours or those of the accessory muscles. When the cause of the entrapment is clearly identified, as is the case with tumours and tarsal coalitions, surgical treatment gives good results, although this is not so in the case of other causes such as post-traumatic and idiopathic ones.9,18

The causes of posterior tibial nerve compression include the presence of the ADLF, which was found by MRI in both ankles of our patient. The prevalence of ADLF in patients with PTTS stands at up to 12% according to some authors. It is more common in men and rarely presents bilaterally.10 In the series reported by Buschmann it amounts to 8%.11 It corresponds to an accessory muscle that may originate from the medial edge of the tibia, the fascia of the deep posterior compartment of the leg, or also from the lateral edge of the fibula, distal to the origin of the FHL.12 Athavale et al.19 in a morphological study of accessory flexor muscles, describe the wide range of anatomical variations of these muscles in terms of their origin, insertion and extension. They found the presence of ADLF in 2 of the 47 cadavers they dissected. In another cadaveric study20 the anatomical detail of ADLF is described; in this cadaver it originated from the posterior crural fascia and proximal portion of the FDL in the proximal third of the deep posterior compartment of the leg, entering the tunnel as a muscle and leaving it as a tendon. On entering the plantar dome of the foot in the second layer of muscles it went laterally to the FDL tendon and superficially to the FHL tendon; the final two of these converged in the knot of Henry. The ADLF was inserted into the FDL tendon just distal to the knot of Henry, where this originates the 4 digital tendons.20 Gümüsalan et al.21 describe the presence of bilateral ADLF in the cadaver of a 57 year-old man, with two muscles originating from the medial edge of the tibia and the lateral edge of the fibula, the posterior intermuscular septum and the deep fascia of the distal part in both legs. Both muscles joined posterior and superficial to the posterior tibial nerve, converging in a single tendon that passed through the tarsal tunnel to end in the plantar square muscle. In our case, MRI of both ankles and the intraoperative findings showed the presence of a thick muscle in intimate contact with the tibial nerve. As was the case in this last case of bilateral PTTS,21 the distal insertion of the ADLF tendon in our patient was into the square plantar muscle. This made it possible to differentiate it from other accessory muscles of the tarsal tunnel, such as the internal peroneocalcaneous and the internal tibialcalcaneus, which are inserted into the calcaneus.

Conservative treatment consists of relieving the symptoms using anti-inflammatory drugs and corticoid injections in the tunnel, as well as the use of an orthesis to reduce the pressure of the tibial nerve in a valgus calcaneus foot.22 Physiotherapy may help to reduce the oedema around the ankle and improve its biomechanics by elongating the gastrocsoleus complex, to minimise the deforming effect of the foot.

Even so, conservative management is not useful if there are lesions that occupy space, so that surgical treatment is indicated. Eberle et al.13 report tenosynovitis of the FHL tendon associated with the presence of ADLF. In their clinical case the authors describe that the ADLF tendon descends posterior and superficial to the tibial nerve, passing under the retinaculum flexor through the tunnel. It is in close contact with the tibial artery and nerve, the FHL tendon in its sheath or immediately parallel with it, thereby explaining the symptoms of FHL tenosynovitis. Ogut et al.,23 report a similar case of stenosing tenosynovitis of the FHL by an ADLF treated initially using endoscopic debridement. Two years later the symptoms reappeared. The patient was subjected to resection of the ADLF muscle, and the symptoms resolved completely. Although rear foot endoscopy is a diagnostic tool for those cases when MRI gives poor visualisation, it requires resection of the accessory muscle for symptomatic relief. Batista et al.24 describe the presence of ADLF as a finding in two patients subjected to ankle endoscopy due to posterior entrapment and posteromedial osteochondral lesion of the talus. These authors underline the importance of being aware of this anatomical variation when performing an endoscopy of the rear face of the ankle.

Resection of the ADLF generally gives good results,14 and it is recommended that neurolysis be performed in scar tissue and adherences around the nerve. Detailed knowledge of normal anatomy and variations is required to free the nerve and its branches while also avoiding iatrogenic injuries. The flexor retinaculum or lanciniate ligament must be freed, together with the deep and superficial fascia of the abductor hallucis.

In a series of 60 surgically-treated patients, Gondring et al.25 found that 85% of them improved their symptoms objectively. Nagaoka et al.26 and Urguden et al.27 reported that space-occupying lesions within the tunnel are rare, although resecting them is associated with good clinical outcomes, particularly when this occurs a short time after the appearance of the symptoms. Kinoshita et al.10 treated 41 patients (49 feet) with tarsal tunnel syndrome, of which 7 had an accessory muscle (6 ADLF and one accessory soleus muscle). All of these patients had improved following resection and surgical decompression after 4.1 months of follow-up.

It is of interest to point out in our clinical case that the patient referred to pain in both ankles; MRI identified a bilateral ADLF unconnected with the synovial sheath of the FHL tendon, as is reported classically.11–14,25,26 Burks et al.15 and Saar et al.16 report clinical cases of unilateral PTTS in which complete symptomatic relief occurred following the resection of the whole accessory muscle. Although the clinical case of Eberle et al.13 was also bilateral, the patient only presented pain in one ankle, with a good postoperative outcome. In this case the ADLF tendon shared the sheath with the FHL tendon, causing tenosynovitis which remitted once the accessory tendon had been resected. Bilateral surgery was performed in our case; this is rare, and the ADLF was also found to be connected to the FDC tendon sheath. We believe, as do other authors, that the tarsal tunnel should always be freed sequentially, following the steps of Lam's technique.2

ConclusionCareful decompression of the tarsal tunnel in our patient with symptomatic bilateral PTTS due to an ADLF led to a good outcome, and he returned to his daily life and sports activity without pain. Nevertheless, in spite of correct surgical treatment a poor outcome is possible, above all if the patient is operated following a long period of time with symptoms.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animals subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments took place in human beings or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their centre of work on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the paper. This document is held by the corresponding author.

FinancingNo financing whatsoever was received.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Schmidt-Hebbel A, Elgueta J, Villa A, Mery P, Filippi J. Síndrome del túnel del tarso posterior bilateral por músculo flexor digitorum longus accesorio; reporte de un caso y descripción de técnica quirúrgica. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:117–123.