Hallux rigidus is the most common arthritis of the foot and ankle. There are numerous reviews on the surgical treatment, but few publications that address the effectiveness of conservative treatment.

ObjectiveTo present a comprehensive algorithm for treatment of all grades of this disease.

MethodsLiterature search in the following sources: Pubmed and PEDro database (physiotherapy evidence database) until October 2013 for articles on treatment of H. rigidus to record levels of evidence.

ResultsA total of 112 articles were obtained on conservative treatment and 609 on surgical treatment. Finally, only 4 met the inclusion criteria.

ConclusionsThe use of orthoses or footwear modifications, infiltration with hyaluronate, cheilectomy in moderate degrees and the metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis for advanced degrees are the only procedures contrasted with grade B or moderate evidence in the treatment of H. rigidus.

El hallux rigidus es la artrosis más frecuente en el pie y tobillo. Existen numerosas revisiones respecto al tratamiento quirúrgico, pero escasas publicaciones que aborden la eficacia del tratamiento conservador.

ObjetivoPresentar un algoritmo global de tratamiento completo para todos los grados de esta enfermedad.

MétodosRevisión sistemática de la evidencia disponible hasta octubre de 2013 utilizando las siguientes fuentes: Pubmed y PEDro database (physiotherapy evidence database) de artículos sobre tratamiento de hallux rigidus que comuniquen sus resultados y de los que pudieran obtenerse grados de recomendación.

ResultadosObtuvimos 112 artículos sobre tratamiento conservador y 609 sobre tratamiento quirúrgico. Finalmente solo 4 cumplían los criterios de inclusión.

ConclusionesEl uso de ortesis a medida o modificaciones del calzado, la infiltración con hialuronato, la queilectomía en grados moderados y la artrodesis metatarsofalángica en grados avanzados, son los únicos procedimientos contrastados con grado de evidencia B o moderada en el tratamiento del hallux rigidus.

Hallux rigidus is a degenerative involvement of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint and the sesamoid complex characterized by pain, restriction of movement and periarticular osteophytosis.1,2 It represents the second most common pathology in the first MTP joint after hallux valgus and is the most frequent osteoarthritis (or arthrosis) in the foot and ankle, affecting 2.5–5% of the population aged over 50 years.2 It is more frequent among females and two-thirds of patients report a positive family history. In such cases, it is a bilateral procedure in up to 95% of cases.2

Various etiologies have been proposed, although the exact cause has not been determined. At present, it has been demonstrated that it has no relationship with hypermobility of the first radius, contracture of the Achilles tendon or gastrocnemius, structural alterations of the foot (like flat foot), hallux valgus, metatarsus primus elevatus, onset of the disease in adolescence, occupation of the patient and/or type of footwear.1 Regarding the length of the first metatarsal, multiple studies have found no relationship with H. rigidus, although there are classical links between a first long metatarsal and this disease. Thus, in our country, Calvo et al.3 described a possible etiopathogenic relationship between both entities, presenting a new method to measure the importance of the length of the first metatarsal and the proximal phalanx in this process. The diagnosis is eminently clinical: mechanical joint pain with reduction of maximum dorsiflexion.1,2,4 Several classifications have been described (Regnauld, Hattrup and Johnson, Núñez-Samper3) with ample interobserver variability, but perhaps the most complete and applicable is that developed by Coughlin and Shurnas,5 which is the one used in our final treatment algorithm, distinguishing from grade 0 to grade IV according to the severity of joint involvement. The initial treatment should be conservative, and when this fails, surgical treatment can also be indicated, distinguishing between procedures which preserve or sacrifice the metatarsophalangeal joint.4

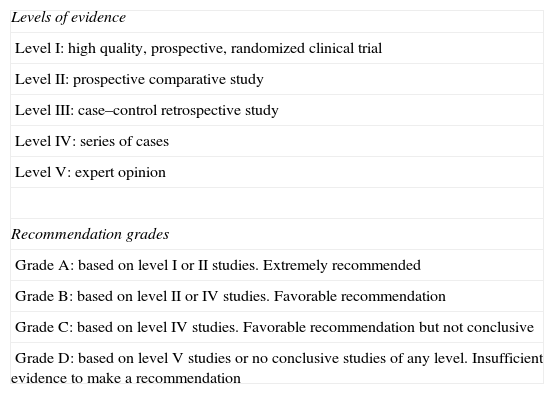

JustificationThe literature contains various reviews on the treatment of this pathology, but we have not found any which approached the evidence in treatment, not only surgical, but also conservative, in an overall manner. Therefore, we do not know whether our daily practice in the prescription of these therapies is supported by scientific evidence.6–8 Evidence-based medicine consists in the integration of the individual clinical experience of healthcare professionals with the best evidence from scientific research, once this has been thoroughly and critically reviewed.6 In essence, it aims to provide the best scientific information available to apply it to clinical practice. The level of clinical evidence is a hierarchical system which assesses the strength or solidity of evidence associated with the results obtained for a healthcare intervention and is applied to tests or research studies. Moreover, the different levels of evidence determine the recommendation grade according to evidence-based medicine4 (Table 1).

Levels of evidence and recommendation grades.

| Levels of evidence |

| Level I: high quality, prospective, randomized clinical trial |

| Level II: prospective comparative study |

| Level III: case–control retrospective study |

| Level IV: series of cases |

| Level V: expert opinion |

| Recommendation grades |

| Grade A: based on level I or II studies. Extremely recommended |

| Grade B: based on level II or IV studies. Favorable recommendation |

| Grade C: based on level IV studies. Favorable recommendation but not conclusive |

| Grade D: based on level V studies or no conclusive studies of any level. Insufficient evidence to make a recommendation |

To review the quality of the available literature for the overall treatment of H. rigidus, both conservative and surgical, establishing a final treatment algorithm to act as a clinical guideline based on the available scientific evidence.

Materials and methodsIn order to elaborate this article, we followed the guidelines proposed by the PRISMA declaration9 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses), to improve the quality of presentation of systematic reviews and metaanalysis, published in 2011.

We used the Jadad scale or score,6 also known as the Oxford quality scoring scale, to evaluate the clinical trials which did not report a recommendation grade. This questionnaire assigns a score from 0 to 5 points, with the highest score associated to a better methodological quality of the randomized clinical trial being assessed. Randomized clinical trials with a score of 5 points are considered as “rigorous”, whereas scores under 3 points are associated with trials of poor quality.

Sources of information and search strategyAn exhaustive and systematic review was conducted by 4 independent reviewers (MHP, JBD, CAB, AB) during November 2013, using the following sources: Pubmed and PEDro databases (physiotherapy evidence database).

Search interval: up to October 31st, 2013.

Selection of studiesThe references obtained from the previously mentioned databases were assessed by the 4 independent reviewers, examining the title and abstract. The following were accepted as inclusion criteria: clinical trials, prospective studies, metaanalysis and systematic reviews on conservative or surgical treatment of H. rigidus which communicated their results and provided a recommendation grade according to evidence-based medicine (Table 1). We only included articles in English and Spanish.

- -

Search criteria in conservative treatment with the following keywords in English and their corresponding terms in Spanish: H. rigidus and “conservative treatment”, “non-operative treatment”, “manual therapy”, “chiropractic therapy”, “physical therapy”, and “injection”.

- -

Search criteria in surgical treatment with the following keywords in English and their corresponding terms in Spanish: H. rigidus (arthrodesis or arthroplasty or osteotomy or cheilectomy or osteophytectomy or exostectomy or surgery).

Articles in languages other than English and Spanish, case reports, articles describing surgical or chiropractic techniques, articles about experimental techniques, biomechanical studies, studies on cadavers and artificial bones (saw bones), articles which did not communicate their results, and articles which did not provide a level of evidence.

Final selection criteriaStudies with recommendation grade A or B and/or Jadad score over 3.

ResultsThe search returned a total of 112 articles on conservative treatment, which were reduced to 67 after applying our exclusion criteria. Of these, only 16 communicated their results and, lastly, only 7 reported on the level of evidence8,10,11,14–17: 2 randomized prospective, 4 systematic reviews and 1 retrospective study, although only 1 of them had a recommendation grade B or moderate or a Jadad score above 3 (Fig. 1, Table 2).

Articles on conservative treatment with recommendation grade B or Jadad score >3.

| Type of study | Intervention | Follow-up (months) | Excellent or good result (%) | Comparison |

| Pons et al.17 Prospective comparative (level II) | A: hyaluronate (n=20) B: corticoids (n=20) | 12 | Improvement of VAS and AOFAS at 3m in both groups. Improvement of pain in the hyaluronate group higher at 1 month and at 3 months | After 1 year, a high percentage of both groups required surgery (46.6% and 52.9%).Moderate or B treatment recommendation, especially for hyaluronate with higher effectiveness in the first 3 months |

VAS: visual analog scale.

We obtained a total of 609 articles on surgical treatment. Of these, applying the exclusion criteria, eliminating repeated articles, those with confusing results and those dealing with various pathologies of the forefoot (not only H. rigidus), we were left with 240 articles. After applying the exclusion criteria only 157 communicated their results and only 141 provided a level of evidence. Lastly, only 3 had a recommendation grade B or moderate or else a Jadad score over 3 (Figs. 2 and 3, Table 3).

Articles on surgical treatment with recommendation grade B or Jadad score >3.

| Type of study | Intervention | Follow-up (months) | Excellent or good result (%) | Comparison | Recommendation |

| Gibson and Thomson43: randomized, controlled clinical trial (level I) | A: arthrodesis (n=34)B: prosthesis (n=30) | 24 | A: 94% function; 100% appearanceB: 83% function; 97% appearance | In both cases, improvement of the pain scores. Arthrodesis better AOFAS, less complications and higher patient satisfaction than prosthesis | Recommendation grade B or moderate for arthrodesis versus MTP prosthesis |

| Roukis and Townley36: prospective cohort (II) | A: BIOPRO superficialization prosthesis (n=9)B: periarticular osteotomy (n=16) | 12 | High percentage of satisfaction in both groups | No statistically significant differences between both groups in relation to AOFAS, plantar flexion or dorsiflexion | |

| Kilmartin30: prospective cohort (II) | A: phalangeal osteotomy (n=49)B: shortening osteotomy of the first metatarsal (n=59) | A: 29B: 15 | A: 90%B: 68% | Less satisfaction in results with metatarsal osteotomy versus phalangeal |

MTP: metatarsophalangeal.

Numerous treatments have been described but scientific evidence is scarce.10–17 Nevertheless, most authors recommend conservative treatment before considering surgery.1,2,4 Thus, Grady et al.11 reported up to 55% of favorable results in their retrospective study of 772 patients treated through conservative measures (level IV).

Physiotherapy treatment- -

Manual therapy. There are reports of traction exercises on the axis of the first radius,12 mobilization of the sesamoid complex, strengthening of the flexor hallucis longus13 and short plantar musculature, but their evidence level is low. The Cochrane systematic review in 2010 only found 1 randomized and controlled study of 2 different physical therapies carried out on 20 patients suffering H. rigidus, although with evidence level C (weak).10 The 2 systematic reviews conducted by the group of Brantingham14,15 on manipulations reported a level of evidence C (weak) for this technique.

- -

There have been recommendations for the use of footwear with a wide toe, low heel, rocking sole and plantar orthesis with a retrocapital bar, always better when tailor-made than prefabricated (recommendation B or moderate). These can reduce symptoms (in the study by Grady et al.11 47% of patients responded to the use of insoles) but are generally poorly tolerated.

- -

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics. We did not find any articles which specifically related effectiveness to improve symptoms in patients with H. rigidus. They were not systematically recommended.

- -

Infiltrations. Solan et al.16 described the manipulation technique under anesthesia and infiltration of corticoids plus anesthetic, reporting its effectiveness in initial stages, as long as there is no prominent dorsal osteophyte, which clearly reduces the clinical response (level IV). An interesting article is that by Pons et al.17 which compared infiltration with corticoids versus hyaluronic acid. These authors demonstrated a reduction in pain in both groups in the short term (3 months) and a trend toward less pain for a longer time in the hyaluronate group. However, approximately half of the patients in each group required surgery after 1 year of follow-up (level II).

Recommendation grades: the literature justifies attempting a conservative treatment before surgery, especially regarding modifications of footwear, the use of tailor-made plantar ortheses and infiltrations (recommendation B or moderate), preferring hyaluronate before corticoids. There is insufficient scientific evidence to justify the use of anti-inflammatory and analgesic drugs (recommendation D or insufficient) and manual therapy (physiotherapy) in all its modalities (recommendation C or weak).

Surgical treatmentSeveral surgical procedures have been described for patients in whom conservative treatment failed.4,18 A very useful practical classification distinguishes between:

- -

Procedures which preserve the joint: procedures on soft tissues, cheilectomy, periarticular osteotomies, and interposition arthroplasty.

- -

Procedures which sacrifice the joint: arthrodesis, resection arthroplasty and partial or total replacement arthroplasty.

The final decision about the most adequate treatment is not a simple one and should take into account the following factors19,20: age, level of activity, severity of the clinical and radiographic disease, associated comorbidities, the wishes of patients and their collaboration with instructions established in the postoperative period, as well as the knowledge by the surgeon of the different techniques described.

Procedures on soft tissuesThe reviewed literature contains scarce material in this respect. However, the development of arthroscopic techniques has increased its importance. The existing reports have mainly referred to the initial stages of H. rigidus, and include clinical results with the following techniques:

- -

Open or arthroscopic synovectomy: indicated in Coughlin grade 0 (negative radiography and synovial thickening).4

- -

Isolated release of the plantar capsule and plate. Advocated by the group of Giannini.21

- -

Release of the tenosynovitis of the flexor hallucis longus. For cases in which tenosynovitis of the flexor hallucis longus in H. rigidus grades I or II is diagnosed.1

Recommendation grade D or insufficient. Scarce scientific evidence. In general, they are not recommended.4

CheilectomyIn addition to the classical technique, percutaneous and arthroscopic techniques have also been described (with scarce scientific evidence). Other authors advocate adding microfractures or subchondral perforations to cheilectomy if the head presents areas with a severe loss of cartilage.22 The objective of cheilectomy is to obtain a resection which enables an intraoperative dorsiflexion of 60–70°. Some authors advocate adding a dorsiflexor Moberg osteotomy to the proximal phalanx if these 70° are not achieved.23 The known advantages of this technique are preservation of mobility and stability, scarce morbidity and the fact that it does not preclude future treatments. It seems to have become the treatment of choice or gold standard in initial stages (I and II), accompanied, or not, by a Moberg-type osteotomy to increase the range of movement,23 although the evidence is weak (level IV or V studies). There are contradictory reports regarding its effectiveness in more advanced stages (III). In 2013, Bussewitz23 published acceptable results at 3.2 years of follow-up in stages I, II and III, whilst Coughlin5 reserved it only for cases where involvement of the head of the first metatarsal was less than 50%. The failure rate of the isolated technique in advanced stages (grade IV) is up to 37.5%. However, there have recently been reports of acceptable results when combined with Moberg osteotomy (85.2% of satisfied patients and significant improvement in the AOFAS scale after a follow-up period of 4.3 years), as an alternative to metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis, which continues to be the standard.24

Recommendation grades:

Metatarsal osteotomiesTheir objective is to decompress the joint through a shortening of the metatarsal, realign the joint to improve joint balance and correct, if present, metatarsus primus elevatus through plantar flexion of the first radius. Various types have been described: Green-Watermann, Austin-Youngswick, Weil-Barouk, etc.3,5,19,20

The studies reviewed offer scarce evidence, inconsistent data and present series which cannot be compared with each other, although in general they offer good short-term results and a notable increase in long-term complications. Haddad25 published a series with poor results after shortening of the first metatarsal and overload of the sesamoids. It is worth highlighting the study by Roukis,26 consisting in a systematic review of 93 cases in which 22.6% required revision and 30% postoperative metatarsalgia. Nevertheless, Malerba et al.27 published very good results with the implementation of the modified Weil-type osteotomy for the first metatarsal (95% of patients with good or excellent results and only 1 case of postoperative metatarsalgia in a series of 20 patients with grade IIIH. rigidus).

Recommendation grade C or weak. Most studies were level IV and communicated a high rate of postoperative metatarsalgia and long-term complications.2,15,18,19,21

Phalangeal osteotomiesMoberg et al.19,20 popularized dorsiflexor osteotomy with a dorsal base wedge in the proximal phalanx of the hallux. Subsequently, other authors associated it to cheilectomy with good results. Most studies have a scarce number of patients and there is insufficient evidence. More recently, Waizy et al.28 presented a series of 46 patients, comparing isolated cheilectomy and cheilectomy plus a Moberg procedure, and reported similar results in both series, although the level of satisfaction of patients in the group undergoing cheilectomy plus Moberg was notably higher. In their review article, Seibert and Anish29 did not recommend it as an isolated procedure, but rather in combination with a cheilectomy, but the evidence, both isolated and combined is insufficient (D). In an interesting prospective study (recommendation grade B), Kilmartin30 compared phalangeal osteotomy versus metatarsal shortening osteotomy and reported that, although no procedure could be recommended as definitive for the treatment of H. rigidus, phalangeal osteotomy offered less complications and higher satisfaction by patients.

Recommendation grade D or insufficient as an isolated or combined procedure.

Interposition arthroplastyCoughlin grades III and IV obtained worse results with cheilectomy, with the most contrasted surgical options being metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis and total arthroplasty.19 However, the prolonged unload time and the problems with certain types of footwear in the first option and the high rate of revisions in the second option have led to an increase in the popularity of interposition arthroplasty, especially among patients younger than 60 years with advanced grades of H. rigidus (III and IV) who wished to preserve mobility and some stability. Different tissues have been used as biological spacers: extensor hallucis brevis, musculus plantaris, gracilis muscle, etc.1,19,20,31–34 It is also worth highlighting the use of recombinant tissue matrix by Berlet et al.32 Theoretically, this involves less bone resection and greater stability and movement, however, other authors do not find differences between this procedure and the classical Keller option.33 More recently, Hyer et al. obtained successful short-term results using tissue matrix, ideally indicating this technique in active patients with severe H. rigidus, especially those with pain in their metatarsosesamoid joint.34

Recommendation grade D or insufficient: it can be an alternative to fusion in active patients with H. rigidus grades III and IV, although further studies are required to determine which interposition technique is the most adequate.

Total replacement arthroplastyTheoretically, this eliminates pain and maintains stability and mobility. The following options are available:

- •

Silicone implants. Following the initial designs by Swanson with a high failure rate, the latest designs have improved, but there are still concerns about wear and loosening, foreign body reaction and systemic involvement due to silicone microfragments in the bloodstream.1,2,4

Recommendation grade C or weak.

- •

Metal implants. The literature continues to report better results with metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis.1,30

Recommendation grade D or insufficient.

These can be phalangeal or metatarsal hemiarthroplasties. Most studies report high rates of radiolucency and loosenings, with metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis being superior in terms of patient satisfaction, AOFAS scale and visual analog scale.2,4 However, Dos Santos et al.35 recently published a series of 11 patients with H. rigidus grades II and III intervened through metatarsal hemiarthroplasty (Hemicap®) with very good results (improvement in AOFAS scale and decrease of pain).35 Roukis and Townley36 published an article with level II evidence, comparing BIOPRO surface prostheses versus Youngswick or Watermann-type osteotomy of the first metatarsal, and reflected a high percentage of satisfaction in both groups, although with no statistically significant differences between both groups in relation to AOFAS, plantar flexion or metatarsophalangeal dorsiflexion.

Recommendation grade C or weak, although with better results with phalangeal hemiarthroplasty than with metatarsal.

Resection arthroplasty- -

Keller-type: joint decompression resecting the base of the proximal phalanx to create a fibrous new joint. Foreseeable consequences: shortening of the first toe, weakness of propulsion and instability, deformity in hyperextension (cock-up) and transfer metatarsalgia.1,4,19,20 The level II article by O’Doherty mentioned in the review published by Yee4 is a classical reference which communicates better results with the Keller alternative than with arthrodesis in older patients. However, like other authors,18 we consider that it mixes results of hallux valgus and H. rigidus, thus making it difficult to draw conclusions. More recently, Coutts37 published excellent results in terms of pain relief, but with a high rate of transfer metatarsalgia (20%).

Recommendation grade B or moderate. Accepted in elderly patients (>70 years) and those with low functional demands, accepting the foreseeable consequences.

- -

Valenti-type arthrectomy: 90° bone wedge resection, dorsal and mounted on the interline theoretically improving dorsal extension.3 Roukis38 carried out a systematic review in 2010, highlighting the low rate of revisions with this technique (4.6% required a conversion to Keller) in severe H. rigidus, although declaring that it was necessary to establish a prospective comparison with other accepted techniques for advanced grades of H. rigidus.

Recommendation grade D or insufficient.

This is the current gold standard for the treatment of severe, symptomatic H. rigidus (grades III and IV).1,4,20 The best results are related to a correct position of the fusion (10–15° dorsiflexion and 10–15° valgus), although a recent prospective study found no relationship between alignment of the hallux and clinical results.39 In recent years, we have observed a development of intramedullary fixation systems,40 although, from a biomechanical standpoint, dorsal plates plus interfragmental screws seem to provide the most stable synthesis.41 Systems with blocked screws and plates have represented an advance in the world of osteosynthesis, and have recently seen excellent results reported with the use of a dorsal plate with blocked screws and a plantar neutralization screw in the metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis.42 Regarding the comparison of arthrodesis versus total arthroplasty, Gibson et al.43 carried out a prospective and randomized study (level II) and reported that arthrodesis was more effective than total arthroplasty, with up to 16% of early failure of the metatarsophalangeal prostheses.

Recommendation grade B or moderate for the treatment of the final stages of H. rigidus (stage IV).

ArthroscopyIndicated in grades I and II; in grades III and IV there have been reports for the joint preparation prior to arthrodesis. This technically demanding procedure has undergone a notable development. In 1998, van Dijk et al. described its use in athletes with dorsal impingement or in osteochondrosis of the head of the first metatarsal, reporting less surgical aggression and earlier reincorporation to competition.44 Its indications have evolved and it is currently used in cases of: synovitis, extraction of free bodies, exeresis of dorsal osteophyte, initial Coughlin H. rigidus grades I and II, osteochondral lesions and as the first step in metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis.45

Recommendation grade D or insufficient.

Percutaneous or minimal incision techniqueThis treatment has become more extended in the last 15 years. In our environment, Mesa-Ramos46 published a prospective study of 22 cases in which he carried out a percutaneous technique, without implanting osteosynthesis, highlighting a higher effectiveness than the classical treatment in terms of clinical results and patient satisfaction. In spite of these a priori satisfactory results, there are still no available studies with a high level of evidence to justify its widespread use.

Recommendation grade D or insufficient.

Conclusions- 1.

Only the use of tailor-made ortheses, footwear modifications and infiltration of hyaluronic acid have shown moderate evidence in the conservative treatment of H. rigidus.

- 2.

Only metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis in stages III and IV and cheilectomy in selected stages I, II and III have a moderate or B recommendation grade for the surgical treatment of H. rigidus.

- 3.

Adding a Moberg-type phalangeal osteotomy has an insufficient recommendation grade, although it does seem to increase patient satisfaction.

- 4.

To date, there is insufficient evidence to justify the use of periarticular osteotomies (metatarsal or phalangeal), arthroplasties of any kind and arthroscopic or percutaneous surgical techniques for the treatment of H. rigidus.

- 5.

Further clinical trials with a higher scientific quality are required, which examine both the conservative and surgical treatment of H. rigidus, and which enable us to adapt our treatment indications to the available evidence.

Level of evidence II.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Herrera-Pérez M, Andarcia-Bañuelos C, de Bergua-Domingo J, Paul J, Barg A, Valderrabano V. Propuesta de algoritmo global de tratamiento del Hallux rigidus según la medicina basada en la evidencia. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2014;58:377–386.