To describe the demographic and clinical characteristics and treatment of patients with spinal gunshot wounds across Latin America.

Material and methodsRetrospective, multicenter cohort study of patients treated for gunshot wounds to the spine spanning 12 institutions across Latin America between January 2015 and January 2022. Demographic and clinical data were recorded, including the time of injury, initial assessment, characteristics of the vertebral gunshot injury, and treatment.

ResultsData on 423 patients with spinal gunshot injuries were extracted from institutions in Mexico (82%), Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela. Patients were predominantly male civilians in low-risk-of-violence professions, and of lower/middle social status, and a sizeable majority of gunshots were from low-energy firearms. Vertebral injuries mainly affected the thoracic and lumbar spine. Neurological injury was documented in n=320 (76%) patients, with spinal cord injuries in 269 (63%). Treatment was largely conservative, with just 90 (21%) patients treated surgically, principally using posterior open midline approach to the spine (n=79; 87%). Injury features distinguishing surgical from non-surgical cases were neurological compromise (p=0.004), canal compromise (p<0.001), dirty wounds (p<0.001), bullet or bone fragment remains in the spinal canal (p<0.001) and injury pattern (p<0.001). After a multivariate analysis through a binary logistic regression model, the aforementioned variables remained statistically significant except neurological compromise.

ConclusionsIn this multicenter study of spinal gunshot victims, most were treated non-surgically, despite neurological injury in 76% and spinal injury in 63% of patients.

Describir las características clínico-demográficas y el tratamiento de pacientes con heridas vertebrales por proyectil de arma de fuego en una cohorte retrospectiva de centros de América Latina.

Material y métodosEstudio de cohorte, multicéntrico, retrospectivo de pacientes tratados por lesiones vertebrales por proyectil de arma de fuego en 12 instituciones entre enero de 2015 y enero de 2022. Se registraron datos demográficos y clínicos, incluidos tiempo de la lesión, evaluación inicial, variables balísticas y tratamiento.

ResultadosUn total de 423 pacientes con lesiones vertebrales por arma de fuego de instituciones en México (82%), Argentina, Brasil, Colombia y Venezuela. Predominantemente varones, civiles, con profesiones con bajo riesgo de violencia y estatus social medio/bajo. Mayoritariamente, por disparos de armas de fuego de baja energía. Lesiones frecuentemente torácicas y lumbares. Lesión neurológica en n=320 (76%) pacientes, con lesión medular en 269 (63%). Tratamiento frecuentemente conservador, con solo 90 (21%) casos quirúrgicos. Las características que distinguieron casos quirúrgicos de los no quirúrgicos fueron compromiso neurológico (p=0,004), compromiso del canal (p<0,001), heridas sucias (p<0,001), restos de fragmentos de bala o de hueso en el canal espinal (p<0,001) y el patrón de la lesión (p<0,001). Las variables mencionadas se mantuvieron estadísticamente significativas luego del análisis multivariado, excepto el compromiso neurológico.

ConclusionesEn este estudio multicéntrico de víctimas de lesiones vertebrales por proyectil de arma de fuego la mayoría recibió tratamiento no quirúrgico, a pesar de la lesión neurológica en el 76% y de la lesión en la columna en el 63% de los pacientes.

Every day in Latin America, new homicide victims are added to the statistical record. The two American continents account for 37% of all homicides worldwide and most occur in Latin America.1 Predominately affecting young civilians (e.g., non-military, non-police), firearms are involved in three quarters of homicides. Recent statistics indicate 16.4 young people killed by others with firearms per 100,000 youth in Latin America.1,2

Spinal gunshot injuries account for 13–17% of all spinal injuries, with great economic and social impact.3,4 Such injuries are the third most common cause of spinal injury in civilian populations, after falls from a height and motor vehicle accidents.5

Gunshot wounds are penetrating injuries, caused by bullets and those elements that are made up at the moment of the shot.6 Multiple factors, mechanical and biological, differentiate gunshot injuries from blunt high-energy trauma.7,8 Mechanical factors related to the ballistics of the projectile determine the severity of damage and should be evaluated (type of firearms, path/size/speed of projectile and distance between firearm and target).7

More than half of gunshots to the spine affect the thoracic region, followed by lumbosacral (30%) and cervical (20%) wounds.9 Clinical presentation ranges from minimal clinically-significant trauma to complete spinal cord injury and mechanical instability. Neurologic compromise has been reported to occur in 33–92.4% of patients.5 Other organ injuries may occur, sometimes requiring being treated first because they are life-threatening.6

Conservative treatment is frequently indicated. Commonly-accepted indications for surgery include spinal instability, progressive neurological deficits, a cerebrospinal fluid fistula, retained bullet or bone fragments in the spinal canal at the cauda equina level, bullet migration, dirty wounds requiring debridement, and persistent pain due to nerve root compression. Sudden progression of a neurological deficit is one indication for urgent surgical decompression.6–11 The prognosis of a civilian gunshot-induced spinal cord injury correlates closely with the extent of the initial neurological deficit.10

In this study, we sought to characterize the demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of spinal gunshot injury patients spanning multiple centers across Latin America, as well as their assessment and treatment. We also compared patients treated surgically and non-surgically to identify characteristics of the gunshot injury that were predictive of surgical management.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective multicenter cohort study of patients treated for spinal gunshot wounds spanning 12 institutions (3 private centers, 5 public/government hospitals, 3 university hospitals, and 1 military/police hospitals) between January 2015 and January 2022.

All patients treated for spinal gunshot wounds at these centers were included in analysis, except for those who died prior to evaluation, those with soft tissue injuries alone and those lacking adequate medical history records.

Demographic and clinical data were recorded, including the time of injury (time of day and day of week), time from injury to admission to the hospital of record, initial assessment findings, nature of the vertebral gunshot injury, and treatment. Data of interest included patient sex, age, education and socioeconomic level, and country; type of hospital (e.g., public, private, university, military); type of work, categorized by level of gunshot injury risk (e.g., military or police officer versus civilian worker); previous morbidity; previous gunshot injury; and toxicology screening results at the time of hospital admission. Also recorded was whether patients were admitted directly or referred from another medical center and the general mechanism of injury (assault, intentionally self-induced, accidental).

Clinical data extracted from the initial assessment were spinal injury level, injury severity score (ISS),12,13 Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score,14 presence/absence of hemodynamic instability, presence/absence and nature of neurological compromise, American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) score (if applicable),15 and the results of spinal imaging. A broad description of the spinal injury included the site of bullet entry and/or exit; type of wound (clean or dirty); presence/absence and nature of abdominal organ perforation; projectile velocity (low or high); bullet location; number of bullets; nature of the vertebral injury; whether the injury occurred at a single or multiple spinal levels; presence/absence and degree of canal compromise; presence/absence of bullet and/or bone fragments in the canal; presence/absence of dural sac injury; and trajectory of the penetrating bullet according to the NOPAL classification system.16 Spinal gunshot wounds with concomitant visceral perforation and injuries with significant soft tissue destruction as well as local tissue contamination were considered as dirty wounds.3

Treatment data extracted for analysis included the general class of treatment (non-surgical/conservative or surgical); length of delay between the injury and surgery, in hours; whether antibiotic prophylaxis or steroids were used; peri-operative complications and 90 days mortality. Additionally, in surgically-treated cases, data were collected on the surgical approach and specific surgical procedure(s) performed, categorized as fixation, decompression/laminectomy, bullet removal, and/or dural repair, and whether a mini-invasive or conventional open surgery approach was used.

Statistical analysis: Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages, and compared between groups by either Pearson chi-square analysis or Fisher's Exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were summarized as either a mean or median value, depending on the nature of distribution (normal vs. non-normal), along with standard deviation (SD) and minimum-maximum values; and compared between groups using either the unpaired Student's t test or non-parametric analysis (Mann–Whitney U test), depending on the normality of distribution.

Inferential testing consisted of comparing spinal injury patients treated surgically versus non-surgically (conservatively), specifically comparing variables traditionally linked to surgery decision-making patterns. All inferential testing was two-tailed with values of p<0.05 considered statistically significant. The statistical software package SPSS 25 was used for all analysis.

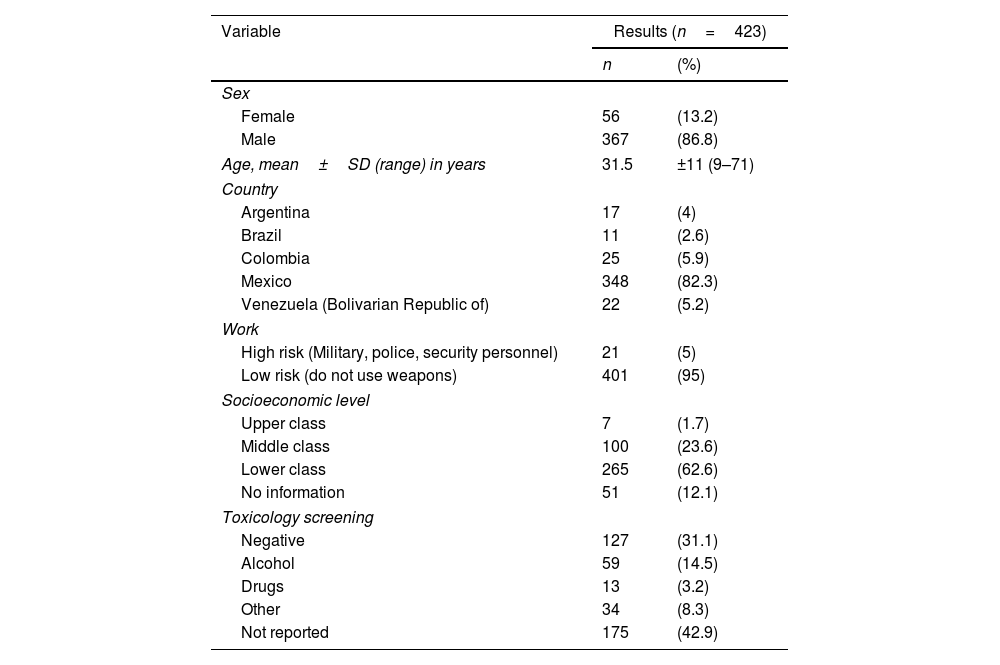

ResultsPatient characteristicsData were extracted on 423 patients with gunshot injuries to the spine treated at trauma centers in Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela, with patients predominantly from Mexico (n=348, 82.3%). Most of the patients had been healthy prior to their trauma (256 with no prior comorbidity; 63%), and a sizeable majority were young males (367; 87%) of lower/middle socioeconomic status (365; 86%). Just over half (217; 51%) had at least completed secondary school. The mean age at admission was 31.5 (SD±11) years old. Less than 1% of cases had suffered a previous firearm projectile wound. Toxicology screening was primarily negative (n=121; 31%) or not reported (n=175; 42.9%) (Table 1). Most patients were treated at a public or government hospital (273; 64.5%), followed by university (113, 26.7%) and military (25; 5.9%) institutions. Only 12 patients in our sample (2.8%) were treated for their spinal gunshot wound at a private institution (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Variable | Results (n=423) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 56 | (13.2) |

| Male | 367 | (86.8) |

| Age, mean±SD (range) in years | 31.5 | ±11 (9–71) |

| Country | ||

| Argentina | 17 | (4) |

| Brazil | 11 | (2.6) |

| Colombia | 25 | (5.9) |

| Mexico | 348 | (82.3) |

| Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) | 22 | (5.2) |

| Work | ||

| High risk (Military, police, security personnel) | 21 | (5) |

| Low risk (do not use weapons) | 401 | (95) |

| Socioeconomic level | ||

| Upper class | 7 | (1.7) |

| Middle class | 100 | (23.6) |

| Lower class | 265 | (62.6) |

| No information | 51 | (12.1) |

| Toxicology screening | ||

| Negative | 127 | (31.1) |

| Alcohol | 59 | (14.5) |

| Drugs | 13 | (3.2) |

| Other | 34 | (8.3) |

| Not reported | 175 | (42.9) |

SD=standard deviation.

The vast majority of the injuries were the result of an assault by another person (403; 95.3%), with just one self-inflicted wound and 19 accidental shootings. The lion's share of injuries (45.6%) occurred during the eight night-time hours from 20:00 to 3:59, including 135 (31.9%) between 20:00 and 23:59h, 58 (13.7%) between midnight and 3:59. Mornings were a low period for gunshot injuries, accounting for just 12.0% between 4:00 and 11:59, with afternoon and early evening (noon to 7:59) accounting for roughly 25%; however, daytime of injury was not reported for almost one in five patients.

54% (n=227) of assaults occurred during weekdays (defined as Mon. to Thurs., n=227; 54%) versus 46% (n=196) over weekends (Fri. to Sun.) plus holidays.

There was a wide range in the duration of time, in hours, between trauma and admission to the center at which the patients were definitively treated (19.5; SD±72.7; range: 0–720), with 183 cases (43%) referred from other centers.

Initial assessmentVertebral injuries mainly affected the thoracic and lumbar spine. Neurological involvement (spinal cord injury or radicular injury/cauda equina syndrome) was documented in 320 (76%) patients, and spinal cord injuries in 269 (63%). In terms of neurological compromise, AIS grade A injuries (full motor and sensory loss below the injury) accounted for almost half of the injuries (49%) followed by AIS grade E (normal neurological function, n=83; 20) (Table 2).

Initial assessment of the injury and spinal gunshot wound.

| Variable | Results (n=423) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| Injury level | ||

| Upper cervical | 16 | (3.8) |

| Lower cervical | 74 | (17.5) |

| Thoracic | 192 | (45.4) |

| Lumbar | 133 | (31.4) |

| Sacral | 7 | (1.7) |

| Multiple | 1 | (0.2) |

| Associated injuries | 349 | (82) |

| Neurological compromise | ||

| None identified | 83 | (19.6) |

| Radicular injury | 51 | (12.1) |

| Spinal cord injury | 269 | (63.6) |

| Not evaluable | 20 | (4.7) |

| AIS | ||

| A | 202 | (49.0) |

| B | 22 | (5.3) |

| C | 51 | (12.4) |

| D | 32 | (7.8) |

| E | 83 | (20.1) |

| NT | 22 | (5.3) |

| Bullet entry | ||

| Head | 23 | (5.4) |

| Neck | 77 | (18.2) |

| Thorax | 177 | (41.8) |

| Abdomen | 136 | (32.2) |

| Pelvis | 9 | (2.1) |

| Multiple | 1 | (0.2) |

| Bullet exit | ||

| Head | 2 | (0.5) |

| Neck | 20 | (4.7) |

| Thorax | 65 | (15.4) |

| Abdomen | 41 | (9.7) |

| Pelvis | 5 | (1.2) |

| None | 289 | (68.5) |

| Wound | ||

| Clean | 326 | (77.3) |

| Dirty | 96 | (22.7) |

| Bullet location | ||

| Vertebral canal | 60 | (14.2) |

| Vertebral body | 38 | (9.0) |

| Posterior arch | 29 | (6.9) |

| Intervertebral disk | 6 | (1.4) |

| Soft tissue | 96 | (22.7) |

| Internal organ | 17 | (4.0) |

| Limbs | 1 | (0.2) |

| Multiple locations | 46 | (10.9) |

| Other | 129 | (30.6) |

| Vertebral injury | ||

| Lamina | 157 | (37.5) |

| Vertebral body | 134 | (32.0) |

| Intervertebral disk | 4 | (1.0) |

| Unilateral pedicle | 59 | (14.1) |

| Bilateral pedicle | 10 | (2.4) |

| Unilateral lateral mass/articular facet | 48 | (11.5) |

| Bilateral lateral mass/articular facet | 7 | (1.7) |

| Bullet's trajectory | ||

| Non-penetrating tangential | 74 | (17.6) |

| Penetrating tangential | 69 | (16.4) |

| Penetrating | 87 | (20.7) |

| Transfixing | 191 | (45.4) |

SD=standard deviation; ISS=Injury Severity Score; AIS=ASIA Impairment Scale; CT=computed tomography; MRI=magnetic resonance image; NT=not testable.

Almost all the vertebral injuries underwent imaging with CT (400; 94.6%), with roughly half examined with plain radiographs (203; 48%). Only a few patients had an MRI (n=30; 7%) or some other imaging study (23; 5%; including dynamic X-rays, angiotomography). Associated injuries were reported in 83% of the patients (n=349), and the mean Injury Severity Score (ISS) among the n=171 patients who had this documented was 23 (±22 SD).

Vertebral gunshot injuryAlmost every injury was caused by a conventional (410; 97%), low-velocity (361; 85%) firearm. Most bullets entered the body via either the thorax (177; 41.8%) or abdomen (136; 32%), and 77.3% (n=326) of the wounds were considered clean (326; 77%). Abdominal organ perforation was documented in 140 (33%) patients. No bullet exit wound was described in 289 cases (68.5%). The spinal canal was frequently affected (59.7%). In addition, in 82% of cases the bullet's trajectory compromised the vertebral canal either directly (penetrating or transfixing injury) or indirectly (penetrating tangentially). More than one third of spinal fractures (157; 37%) involved the lamina, followed by the vertebral body in 32%. Bilateral facet (7; 2%) and pedicle injuries (10; 3%) both were rarely reported in our sample (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

TreatmentThe usual treatment of firearm vertebral injuries was conservative and accompanied by antibiotic prophylaxis. Use of steroids was reported in just 20 (5%) cases. Only 90 (21%) patients were treated surgically, principally accessed using the posterior open midline approach to the spine (79; 87%). Surgical management included bullet removal (24; 27%), fixation (17; 19%), decompression (27; 30%), and dural repair (8; 9%). Use of minimally-invasive surgery was rare (2.2%).

The overall complication rate of gunshot injury to the spine was 36% (156) and most were linked to associated injuries (80; 18.9%). Persistent pain was the most prevalent complication, followed by sepsis/septic shock, pneumonia and neurogenic bladder. There were just four post-operative complications (4% of the surgical cases). The 90 days mortality rate was 6.4% (n=27).

Comparing surgical versus conservative treatmentSurgical treatment was associated with neurological compromise (p=0.004) canal compromise (p<0.001), dirty wounds (p<0.001), bullet or bone fragment remains in the canal (p<0.001) and injury pattern (p<0.001) (Table 3).

Comparing patients treated surgically versus non-surgically.

| Variable | Surgery (n=90) | Conservative (n=333) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Neurological compromise | 82 (91) | 258 (77) | 0.004 |

| Dirty wound | 35 (38) | 61 (18) | <0.001 |

| Abdominal organ perforation | 25 (28) | 115 (34) | 0.220 |

| Canal compromise | 73 (81) | 179 (53) | <0.001 |

| Bullet or bone fragments remains in the canal | 61 (68) | 110 (33) | <0.001 |

| Injury pattern | |||

| Lamina | 24 (26) | 133 (40) | <0.001 |

| Vertebral body | 35 (39) | 99 (30) | |

| Disk | 3 (3) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Pedicle | 8 (9) | 61 (18) | |

| Facet | 20 (22) | 35 (10) | |

After a multivariate analysis through a binary logistic regression model, the aforementioned variables remained statistically significant except neurological compromise. Dirty wounds (p=0.07; OR=2.178; 95% CI=1.236–3.836); canal compromise (p=0.005; OR=2.6; 95% CI=1.338–5.5286); bullet or bone fragments remains in the canal (p=0.001; OR=2.715; 95% CI=1.504–4.902); and injury pattern (p<0.001) were related to surgical treatment. According to injury pattern subtypes, the differences were statistically significant between lamina versus facets (<0.001 OR=4.755; 95% CI=2.183–10.358).

DiscussionOur cohort of spinal gunshot injury patients from across Latin America was heavily represented by young males in low-risk-of-gunshot-injury jobs (e.g., non-military or police) who suffered low-energy gunshots to the spine, similar to the demographics reported in previous publications from Latin America and other world regions.6,9,11,17–21 Almost all patients were lower/middle class victims of firearm violence, in line with the results of a United Nations study.2 To better describe this scenario, we found similar numbers of gunshot injuries to the spine on weekdays and weekends/holidays, but a preponderance of injuries late at night and in the wee hours of the morning (before 4:00).

As described previously in other retrospective studies, the lion's share of injuries were to the thoracic spine (45%),6,9,18 but we also found more upper cervical injuries than previously reported (3%).6,9

Gunshot injury patients have a wide range of clinical presentations on admission, from isolated, stable vertebral fractures to severe cases of multiple trauma for which treatment is both complex and challenging.6 In our sample, 75% of the patients presented to us with a neurological deficit, 11% with a Glasgow Coma Scale score under 8, and 38% hemodynamically unstable. Associated injuries were the rule (82%), with the mean Injury Severity Score equal to 23 (±22), when recorded; unfortunately, the ISS was reported in just a minority of patients (171, 40.4%).

In a recent systematic review of the literature, the rate of complete spinal cord injury reported was found to range from 13% to 78%.22 In our sample, 320 (76%) patients exhibited some level of neurological compromise and almost half were classified as having AIS grade A injuries, indicating the complete loss of both motor and sensory function below the injury.

Computed tomography and radiographs have classically been proposed as the gold standard for assessing bone injury patterns and the mechanical stability of spinal gunshot injuries.3,4,10,22 Tomography provides an accurate assessment of bullet location, delineates any bone damage, and identifies bullet and bony fragments within the spinal canal.3 Few indications support the use of MRI in spinal gunshot patients due to concerns about the effect of the magnetic field on the components of ferromagnetic bullets that could exacerbate the original injury.23 Almost every patient in our cohort had their spinal injury assessed via CT (94%), with roughly half having radiographs (48%). MRI was performed in just 30 patients. Injuries mainly affected the vertebral canal (60%), lamina (37%), and vertebral body (32%).

Treatment of patients with penetrating trauma should be guided by Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) principles, which argue for life-threatening injuries to be identified and treated immediately.3 Tetanus vaccination status should be checked and broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started immediately and continued for 48–72h in all cases.3 The full duration of antibiotic treatment remains controversial, however. Retrospective reviews have highlighted how perforated abdominal organs and, especially, wounds that perforate the colon confer a much higher risk of infection and should be treated with longer-term antibiotic coverage to prevent deep spinal infections.20 Prophylactic antibiotic treatment was used in 94% of our sample cohort.

We noted a low rate (<5%) of high-dose steroid use at our 12 Latin American centers, consistent with the body of published evidence suggesting that they typically are contraindicated in patients with penetrating trauma.22,24

Surgical treatment of spinal gunshot injuries remains controversial.3,10,22,25–27 The surgical indications most frequently discussed in the literature are neurological decompression, removing bullets in the vertebral canal, repairing cerebrospinal fluid leak, and treating spinal instability.3,5–7,10,25,26 In our retrospective analysis, surgical cases were more frequently associated with certain injury patterns that included vertebral canal compromise, dirty wounds, bullet or bone fragment remains in the canal, and injuries to the lamina, all of which is consistent with the literature.

Spinal gunshot wounds are commonly thought to be stable, but there is a lack of consensus on the definition and classification of unstable fracture types. Gunshot injuries that fracture both pedicles or facet joints have been proposed to be unstable and require fixation.6,26 In our sample, fewer than 3% of the patients had this type of injury, so we cannot expand upon current literature regarding this issue.

Our study has several limitations, which include the retrospective nature of data collection, a sizeable percentage of missing data for some variables, and the highly disproportionate number of patients from a single country. Fortunately, the vast majority of missing data were among demographic variables and the time of day when the injury occurred, all of which have been reported elsewhere; while almost all the variables related to the nature of the injury and treatment provided were fully or near complete.

ConclusionsThis study describes a Latin American multicenter cohort study of gunshot injuries to the spine. The vast majority of gunshot victims were males in low-risk professions and of lower/middle social status who suffered low-energy firearm assaults. Neurological compromise was the rule, with vertebral canal compromise and fractures of the lamina common, but bilateral facet involvement rare. Treatment was largely non-surgical, with surgical cases distinguished by higher rates of vertebral canal compromise, bullet or bone fragments in the vertebral canal, and fractures involving the lamina.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflicting interests.

The authors acknowledge support from the AOSpine Latin America. This study was organized by the AO Spine Latin America Trauma Study Group and Spinal Gunshot Injuries Group: Michael Dittmar, David Servin, Cristobal Herrera, Cristobal Herrera Palacios, Janicke Rodriguez, Luis Muñiz, Manuel Perez, Juan Mandujano, Rodrigo Garcia, Oscar Montes, Jesahiro Hidalgo, Bairon Lovera, Madeline Bilbao, Marcelo Wirz, Raul Alcaraz, Daniel Ricciardi, Vinícius Marques Carneiro, Denylson Sanches Fernandes. AO Spine is a clinical division of the AO Foundation, which is an independent, medically guided not for-profit organization. The authors would like to thank Idaura Lobo and Carla Ricci (AO Spine) for her administrative assistance.