To present the surgical technique with release of peritendon and radiofrequency as an effective treatment for athletes with chronic tendinopathy of the Achilles tendon body.

Materials and methodsThis is a retrospective case series descriptive type study. The series consists of 17 Achilles tendon surgeries in 13 patients, who habitually run. The study included patients with non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy refractory to conservative treatments. After a minimum follow-up of 12 months, clinical improvement of the athletes was assessed using the Nirschl pain scale, as well as athletic performance.

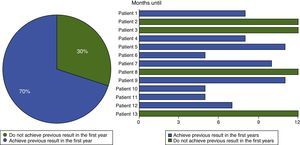

ResultsAn improvement was obtained in 94% of symptoms and a return to the previous performance in 70% of cases in the 12 months follow-up.

DiscussionPeritendon release combined with bipolar radiofrequency is presented as an effective solution in this condition, for which there is currently no consensus on the best treatment. In patients in whom the non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy persists after an appropriate conservative treatment for a sufficient period (at least 6 months), open adhesiolysis combined with bipolar radiofrequency is a safe and with a high success rate clinical and functional intervention. In high performance athletes this technique allows a return to previous activity in a high percentage of cases.

Presentar la técnica quirúrgica con liberación del peritendón y radiofrecuencia como un tratamiento eficaz para los pacientes con tendinopatía crónica del cuerpo del tendón de Aquiles en deportistas.

Material y métodoSe trata de un estudio descriptivo tipo serie de casos retrospectivo. La serie se compone de 17 tendones de Aquiles operados en 13 pacientes, todos ellos practicantes habituales de carrera a pie. Fueron incluidos aquellos pacientes con tendinopatía no insercional del tendón de Aquiles refractaria al tratamiento conservador. Se realizó un seguimiento mínimo de 12 meses, evaluándose la mejoría clínica con ayuda de la escala de Nirschl-Pain, así como el rendimiento deportivo de los atletas.

ResultadosSe obtuvo un 94% de desaparición de los síntomas y una vuelta al rendimiento previo del 70% de los casos en los 12 meses de seguimiento.

DiscusiónLa liberación del peritendón combinada con radiofrecuencia bipolar se presenta como una solución eficaz en esta enfermedad sobre la cual no existe en la actualidad un consenso acerca del mejor tratamiento. En los pacientes que tras un tratamiento conservador adecuado durante un periodo suficiente (al menos 6 meses) persiste la tendinopatía no insercional del tendón de Aquiles, la adhesiólisis abierta asociada a radiofrecuencia bipolar constituye una intervención segura y con una alta tasa de éxito, tanto clínica como funcional. En el deportista de alto rendimiento esta técnica permite la vuelta a la actividad previa en un alto porcentaje.

Non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy is a condition with a high incidence in sports medicine and orthopaedic departments, and it is especially common in runners and athletes.1 It may also affect sedentary individuals, for whom associated microangiopathy is a risk factor, as are being overweight and diabetes.2

It affects amateur as well as professional sportsmen and sportswomen, and it is typical in activities which include running and jumping, such as football and racket sports.3 The highest prevalence of this disease occurs in high level runners, where it affects 7–9% of athletes, among whom it is 10 times more common than it is in control groups with the same age distribution.4 The lifetime risk of Achilles tendon lesions in general among runners has been estimated to stand at 52%.5 The exponential growth in the sociological phenomenon of running in Western countries6 means that the prevalence of this condition is increasing.

Tendinopathy develops due to a combination of two types of factor: mechanical (overuse) and biological (lack of repair).7 This explains its high prevalence in long distance runners, although it does not affect all of them.

The maximum force transmitted by the strong calf muscles is concentrated in the region of the body of the tendon, which may withstand forces of 9000N, i.e., 13 times bodyweight.8 Nevertheless, it is here that Carr et al.9 used angiography to show that there is hypovascularisation where the vessels from the calcaneus and muscle join.

Micro-tears occur in runners in the type I collagen bundles, and under normal conditions they would be repaired.10 However, if the mechanical stimulus persists and surpasses the capacity for repair, the collagen deposited does not have sufficient time to mature, and it is replaced by disorganised bundles of type III collagen between areas of myxoid degeneration.11

Cellular metaplasia occurs at the same time, in which fibroblasts are replaced with myofibroblasts that concentrate in the peritendon, creating adherences and collapsing vessels.12 Large amounts of growth factor are given off by the vascular endothelium, and neovascularisation7 occurs. This is the second phenomenon which together with degeneration characterises non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy, with an incidence in symptomatic tendons of from 70% to 90%.13 This neovascularisation is accompanied by aberrant nerve fibres that cause pain.

There are several options for treatment, and none of them has been established as the gold standard.14 The only consensus is that conservative therapies should be used at the start of treatment.

Nevertheless, we found that in more than one-third of patients conservative treatment fails, leading to the need to evaluate the indication for surgery.3

Patients are often not offered alternative therapies at this time. This situation sometimes includes an emotional component, as patients are unable to compete or at the least have to permanently change their activity.

To date most of the procedures used were restricted to longitudinal tendotomies, macroscopically incising tissues that look devitalised.

Our aim is to present the results of the surgical procedure that consists of the freeing and/or division of the peritendon, adhesiolysis and radiofrequency in patients who are runners with tendinopathy of the mid-part of the Achilles tendon.

Material and methods: our seriesWe present a retrospective and descriptive study of a series of cases.

The series includes all of the patients operated from February 2010 to January 2013 for tendinopathy of the body of the Achilles tendon that fulfilled the following inclusion criteria:

- -

Patients operated using the technique described by the surgeon S. Orava.14 All patients were informed of the procedure and gave their written consent.

- -

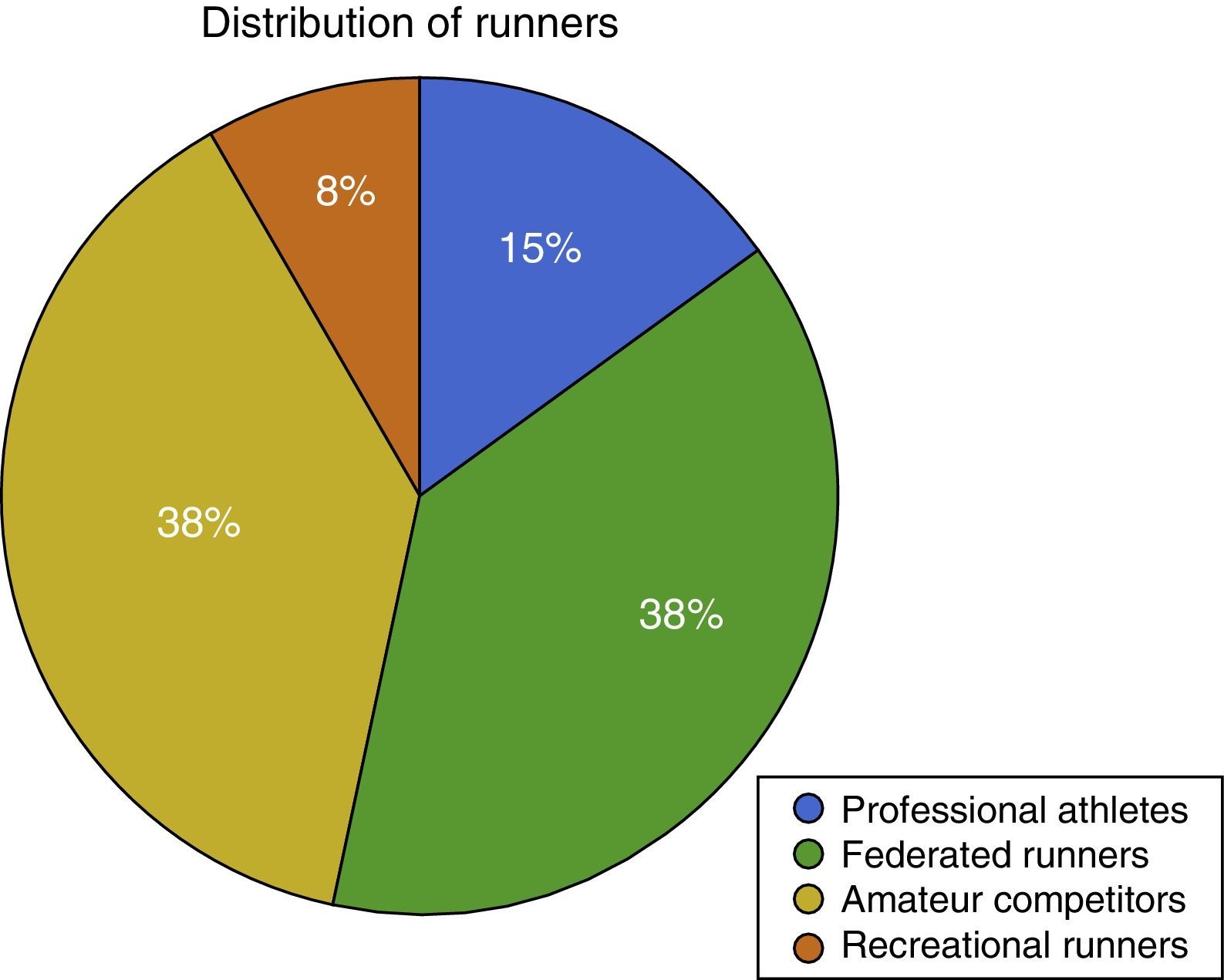

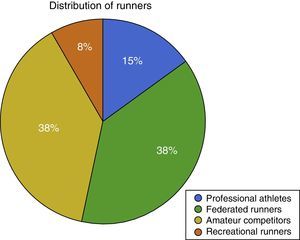

Active patients who practised sport including running every day until they developed tendinopathy. The cohort includes a majority of elite professional athletes as well as very high level amateur athletes (Fig. 1).

- -

Previous failure of at least 6 months of conservative treatment.

- -

Postoperative follow-up of at least 12 months.

The following exclusion criteria were established:

- -

Previous surgery in the affected Achilles tendon.

- -

Partial tears within the tendon detected by MNR or during the operation.

- -

Concomitant insertional tendinopathy in the same limb.

All the patients gave their informed consent for surgery and also consented to the use of their data for publication.

The surgical technique included the opening of the crural fascia, peritendon adhesiolysis using a scalpel and microtendotomy. The microtendotomy was undertaken in the zone of the tendinopathy in the body of the tendon by means of bipolar radiofrequency (the Topaz MicroDebrider® by Arthorcare) (Fig. 2). The tendon was perforated using radiofrequency perpendicular to the surface of the tendon, with a distance between perforations of 5mm and applying pulses at an interval of 500ms. The tendon may vary in thickness from one zone to another, so that superficial and deep perforations were made, creating a square three-dimensional pattern. The tip of the radiofrequency device has a surface area of 0.502mm2 and a radius of action of 2.5mm.

The wound was sutured with non-absorbable thread and the calf and foot were bandaged. Active mobility and isometric exercises were permitted from immediately after the operation, and partial loading using two crutches was permitted the first week. The stitches were removed at 2 weeks and exercise was permitted using an exercise bicycle. At 3 weeks, if the wound had good scar formation, swimming-pool exercise commenced, and after the fourth week exercise using an elliptical trainer was allowed. A physiotherapy protocol was added to this, with drainage of the oedema and manual stretching therapies.

The series consists of 17 cases in 13 patients operated by the same senior surgeon in the CEMTRO Clinic, Madrid.

The demographic data and sports history of each patient are shown.

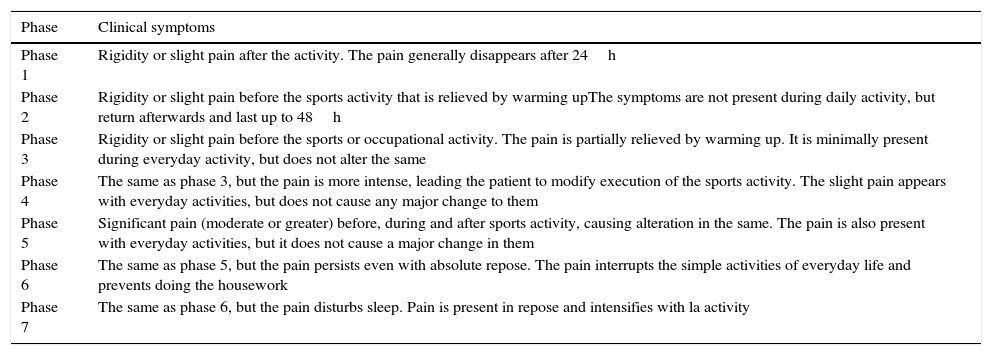

The results were evaluated on the Nirsch-Pain scale (Table 1),14 which includes questions about everyday life as well as about functional repercussions in sport. The visual scales such as VISA-A15 which are usually used for the Achilles tendon were not used here. This was because the condition is related so closely with sports activity that they would not have been useful for patients who only felt pain during exercise. All the patients filled out the questionnaire on the same day of the operation, as well as subsequently during follow-up: at 2, 4, 6 and 12 months.

The Nirschl pain scale.

| Phase | Clinical symptoms |

|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Rigidity or slight pain after the activity. The pain generally disappears after 24h |

| Phase 2 | Rigidity or slight pain before the sports activity that is relieved by warming upThe symptoms are not present during daily activity, but return afterwards and last up to 48h |

| Phase 3 | Rigidity or slight pain before the sports or occupational activity. The pain is partially relieved by warming up. It is minimally present during everyday activity, but does not alter the same |

| Phase 4 | The same as phase 3, but the pain is more intense, leading the patient to modify execution of the sports activity. The slight pain appears with everyday activities, but does not cause any major change to them |

| Phase 5 | Significant pain (moderate or greater) before, during and after sports activity, causing alteration in the same. The pain is also present with everyday activities, but it does not cause a major change in them |

| Phase 6 | The same as phase 5, but the pain persists even with absolute repose. The pain interrupts the simple activities of everyday life and prevents doing the housework |

| Phase 7 | The same as phase 6, but the pain disturbs sleep. Pain is present in repose and intensifies with la activity |

The second parameter patients were asked about during check-ups was the return to previous levels of performance, in terms of objective sport intensity criteria (the time-distance ratio) or frequency.

Prior to surgery patient's sports activity was modified, provisionally replacing running exercises with other less traumatic ones. They were prescribed muscle-building exercises such as closed kinetic chain exercises, as well as cycling. Eccentric exercises according to the Alfredson1 protocols were combined with physiotherapy and the use of nutritional aids.

In all the sports people in the cohort this disease led to a major reduction in their performance as well as withdrawal from competition.

ResultsThe average age of the cohort at the time of the operation was 36 years, while five Achilles tendons were operated in women and 12 in men.

The chief symptom due to which the patients visited was pain (100%) located directly in the tendon body and occasionally radiating out proximally, followed by thickening of the tendon (70%). The pain was more intense at the start of training in the least advanced cases, while in the most advanced cases it prevented normal walking. Diagnosis was clinical, although in all cases magnetic resonance was used to rule out the presence of partial tears and concomitant insertional disease, as well as to stage the degree of tendon degeneration.

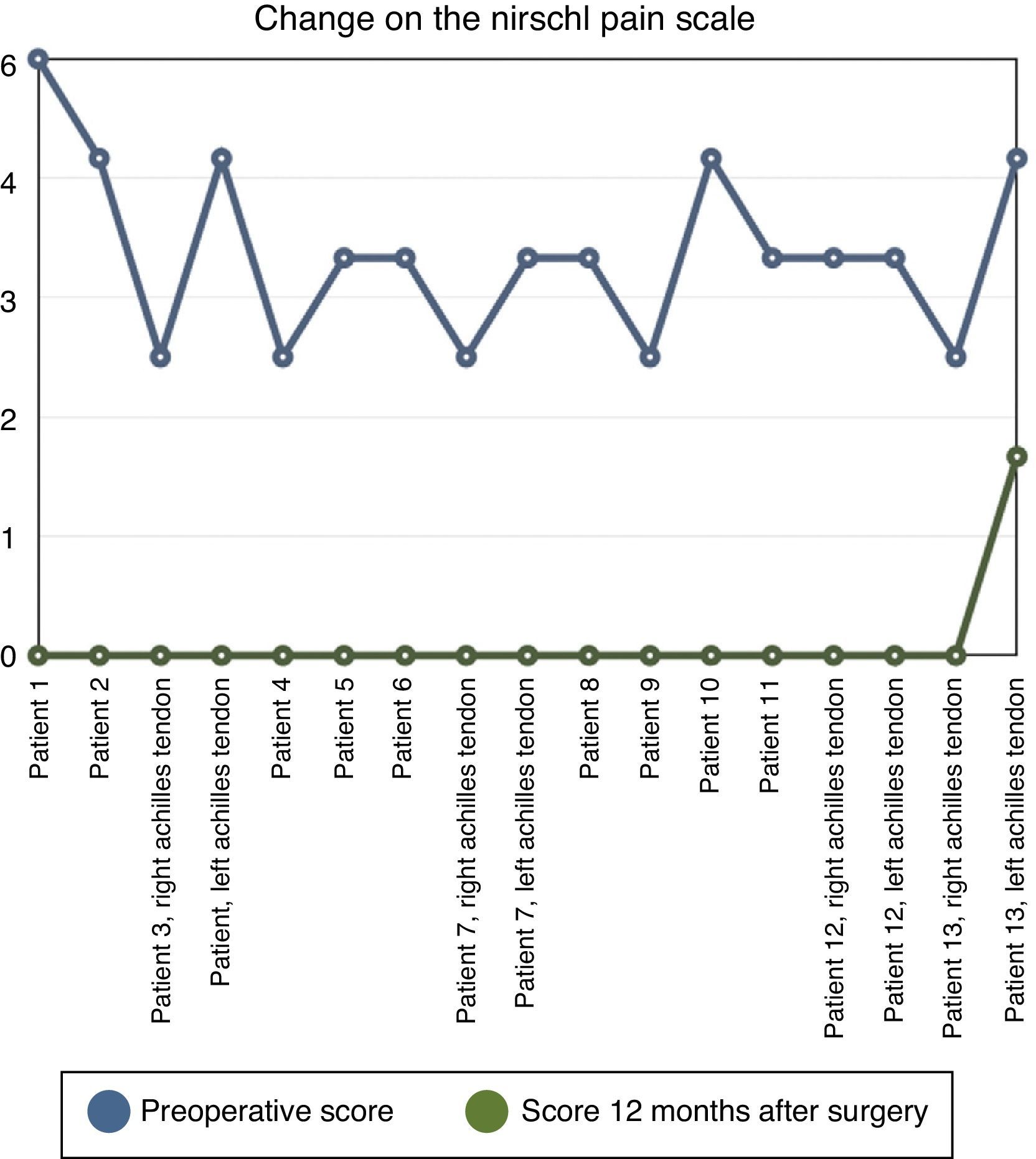

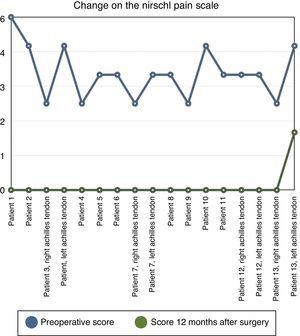

The average score on Nirschl's scale for the tendon involved at the moment of surgery was 4.1 (Fig. 3). This shows that while the pain had little effect on the activities of everyday life, it was a major restriction in sport.

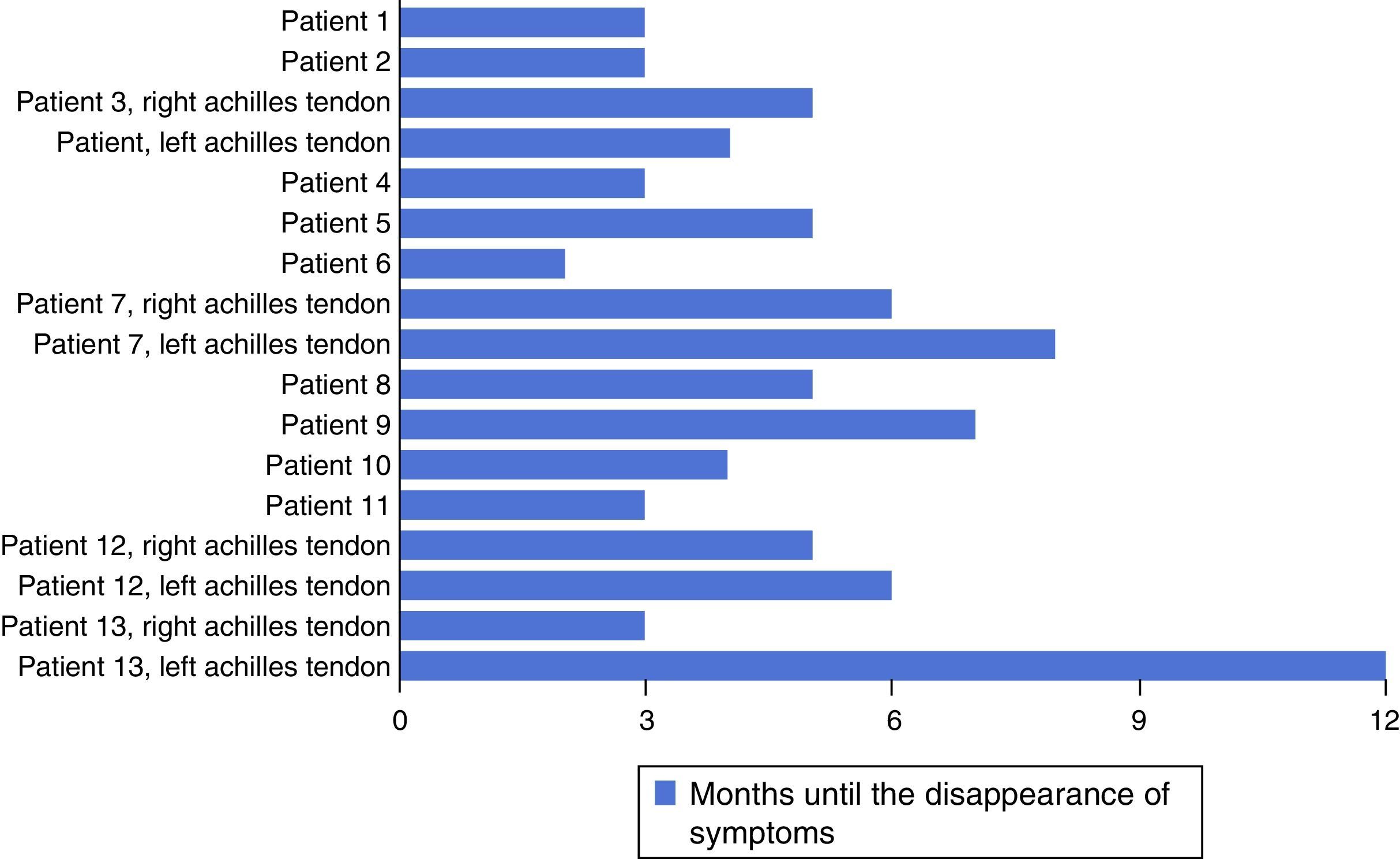

In 16 of the 17 tendons operated the symptoms had totally disappeared 12 months after the operation (94% rate of cure). The pain did not disappear soon after the operation, but rather in the majority of cases this occurred during postoperative rehabilitation.

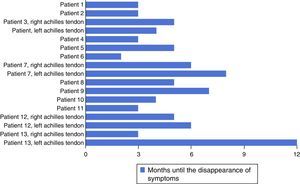

Pain disappeared when running at an average of 17 weeks after surgery (Fig. 4). The symptoms while running had not completely disappeared in one patient after 12 months; this was one of the patients operated bilaterally. Pain had disappeared completely in one leg, while relief was incomplete in the other at 80% (passing from 5 to 1 on the Nirschl scale) (Fig. 3).

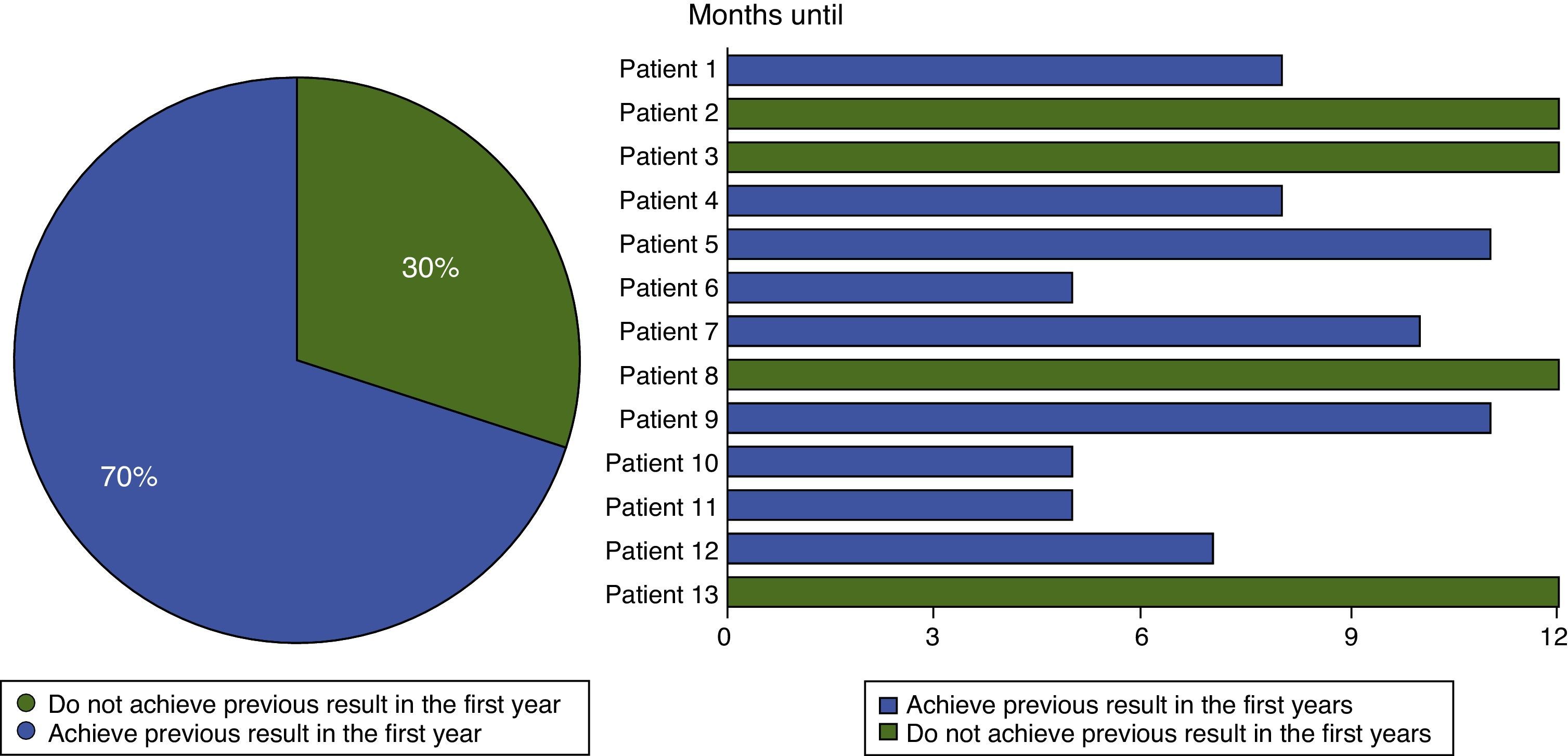

Nine of the 13 patients operated (or 12 of the 17 tendons) returned to their previous level of performance and training prior to the onset of their symptoms. This represents a 70% rate of performance recovery in the 12 months after surgery (Fig. 5).

DiscussionBipolar radiofrequency has been used before in different fields of orthopaedics. A randomised clinical trial recently showed that radiofrequency is a promising alternative in the treatment of refractory epicondilitis,16 and this disease is probably one of those with a physiopathological mechanism most similar to non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy. It has also been shown to be effective in other chronic degenerative tendinopathies such as fasciitis plantar or patella tendinosis, with 95% of good or excellent results.17 It has also been shown to be effective in the treatment of rotator cuff tendinosis in the context of subacromial impingement syndrome.18

Very few works have been published on the medium to long-term follow-up of the use of bipolar radiofrequency in the treatment of Achilles tendinopathy. This is the first study of a homogeneous cohort of sports people which does not include sedentary patients with comorbidity that caused tendinopathy.

Although there is now no set protocol for the treatment of Achilles tendinopathy, almost all authors defend commencing with conservative treatment. Some authors such as Alfredson et al.19 have proposed non-surgical treatment algorithms. Nevertheless, as they mix sedentary patients with others who do sports this may reduce the external validity of their studies.

The conservative treatments best supported by findings are eccentric exercises,1 which are widely used in Scandinavian countries. They involve specific programmes lasting for several weeks or months, and their initial results were very hopeful. However, more recent trials comparing some of these therapies with gentle non-systematic exercises either found no differences or far less optimistic results.20 On the other hand, patient compliance with long-term daily exercises achieves a low level of adherence to the treatment.

Together with eccentric exercises, shockwaves are the conservative therapy that is best supported by the evidence. They act in three ways, by promoting collagen synthesis, destroying amyelinic fibres and hollowing out interstitial tissue. All of this will activate scarring mechanisms. A recent meta-analysis states that this technique is effective after 3 months in refractory non-insertional tendinopathy.21

Respecting pharmacological treatments, the use of NSAIDs is contraindicated by almost all authors. This is because they interfere with cell repair mechanisms, and some studies prove that inflammatory molecules such as prostaglandins are not present in this entity.22

In the same way that NSAIDs do not seem to be useful, corticoid peritendon injections have not been shown to be effective in this condition, although they are for acute peritendonitis. As is the case for all tendons, injections into this tendon must be avoided due to their catabolic effects. Unlike NSAIDs, cryotherapy has been shown to reduce metabolic needs as well as two thirds of capillary flow, which in neovascularisation means reducing the extravasation of proteins that prolong pathogenesis.4

Some articles with a high level of evidence have been published that state that there are no significant differences between the use of platelet-rich plasma and a placebo.23 Nevertheless, other studies have obtained good results with the use of platelet-rich plasma in patients with non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy, without distinguishing subgroups according to their sports activity.24

There are factors which have been shown to predispose runners to tendinopathy.25 These include footwear, training on hard surfaces, lateral instability of the ankle and high arches, and special attention should be paid to these. This is why before indicating surgery we study and modify training habits as a fundamental part of the conservative treatment of our cohort.

According to the majority of publications conservative techniques as a whole are successful in approximately 2/3 of patients. Many works cite permanent changes of activity, based mainly on replacing running with some other type of activity, without which they would probably not achieve such high success rates. On the other hand the results of conservative treatment have been shown to be highly unpredictable in cases which evolved over several months.26

We did not find the same success rates in our experience, given that our patients did not consider ceasing to run or definitively changing their activity as a treatment options.

All of the patients in the series presented tendinopathy that was refractory to combined conservative treatment under our supervision. Other previous conservative treatments which they may have followed without our indication were not taken into account.

Respecting surgical treatment, the majority of authors agree that it should be used in the 25–35% of patients who do not improve with conservative treatments. They state that a waiting time of at least 6 months should be allowed before considering surgery.1,3 It is here that patients of our type usually invest a large amount of time and money in seeking a solution, without finding a standard surgical option.

Surgery aims on the one hand to reactivate or at least stimulate the intrinsic repair mechanisms which failed in conservative options. There are a range of techniques to do this. One example is to make longitudinal incisions, which classically has been taken to be a procedure that promotes the recovery of normal tendon structure; nevertheless, no articles prove that this brings about a clinical improvement.

The other fundamental surgical procedure is the stripping of fibrotic adhesions as well as anomalous vessels and aberrant nerve fibres. Van Dijk et al.13 consider the cutting of the fibres that colonise the tendon from the paratendon to be the objective of treatment using endoscopic technique, without acting on the degenerate tendon itself. There are also other adhesiolysis techniques described by Mafulli et al., such as the ultrasound-guided injection of large volumes of serum into the pre-Achilles zone27 and adhesiolysis by passing Ethibond thread through longitudinal incisions in the tendon (stripping technique).28

The use of percutaneous radiofrequency has been described for insertional Achilles tendinopathy,29 and while this may improve tissue repair, it will not act on peritendon fibrotic adhesions and neovascularisation.

The proximal freeing of the gastrocnemius gives good results in sedentary patients, in whom the postoperative strength of the leg operated does not differ from its preoperative strength;30 however, this may not be the most suitable technique for patients who do sports, given the possibility that the operated leg may lose the strength necessary for running in comparison with the healthy leg.

To try to improve Achilles tendon mechanics after cutting the peritendon pathological tissues, some authors recently suggested lengthening the tendon using the hallucis longus flexor,31 and this may require a subsequent change of activity.

We believe that in patients who are going to demand a high level of mechanical performance, as is the case in our cohort, surgical treatment firstly requires the stripping of all pathological tissue from around the tendon. Doppler ultrasound will show a high increase in vascular flow in the tendon which should not be visible in normal tendons.32 This vascularisation will be what we strip away in the first phase of the operation.

We then act on the tendon itself, activating its overwhelmed repair mechanisms. We use bipolar radiofrequency for this. This technique was first used to treat myocardial ischaemia, in which coblation showed an increase in functional vascularisation.33 The terminal used applies a saline serum that spreads over the tissue at a speed that can be adjusted, which when it makes contact with the electrode creates a jet of steam that consists of an ion-charged plasma field that dries the tissues. Its main advantage vs electrocoagulation is that it acts at physiological temperatures, and its field of action can be adjusted, thereby reducing iatrogenic damage to adjacent structures. This technique is highly reproducible, given the absence of a long learning curve. It is safe due to the small amount of tissue that is dried and the fact that it always occurs at a physiological temperature.

Careful follow-up is as important as appropriate surgical treatment, given that the symptoms may take some time to disappear. During this time it is of fundamental importance for our patient profile to keep fit, so that they will have to perform activities other than running while gradually increasing the intensity at which the operated tendon works.

To conclude, we may say that non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy is an entity that is becoming more common in visits to sports injury clinics due to the increasing popularity of running. Although conservative treatment should be the first choice, specific aspects of highly demanding patients have to be taken into account. If conservative treatment fails, microstripping and coblation of the calcaneus tendon in sportsmen and women is a safe and reproducible technique. It achieves a high rate of return to symptom-free activity as well as to the previous level of sport performance.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed comply with the ethical regulations of the corresponding human experimentation committee, the World Medical Association and the Helsinki declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their hospital on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Arnal-Burró J, López-Capapé D, Igualada-Blázquez C, Ortiz-Espada A, Martín-García A. Tratamiento quirúrgico de la tendinopatía aquílea crónica no insercional en corredores mediante el uso de radiofrecuencia bipolar. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:125–132.