To evaluate with an animal model of osteoarthritis (New Zealand rabbits) the effectiveness of treatment with active viscosupplements (hyaluronic acid loaded with nanoparticles (NPs) that encapsulate anti-inflammatory compounds or drugs.

Material and methodsExperimental study composed of 5 groups of rabbits in which section of the anterior cruciate ligament and resection of the internal meniscus were performed to trigger degenerative changes and use it as a model of osteoarthritis. The groups were divided into osteoarthrosis without treatment (I), treatment with commercial hyaluronic acid (HA) (II), treatment with HA with empty nanoparticles (III), treatment with HA with nanoparticles encapsulating dexamethasone (IV) and treatment with HA with nanoparticles that encapsulate curcumin (V). In groups II–V, the infiltration of the corresponding compound was carried out spaced one week apart.

Macroscopic histological analysis was performed using a scale based on the Outerbridge classification for osteoarthritis.

ResultsWe observed that this osteoarthritis model is reproducible and degenerative changes similar to those found in humans are observed.

The groups that were infiltrated with hyaluronic acid with curcumin-loaded nanoparticles (V), followed by the dexamethasone group (IV) presented macroscopically less fibrillation, exposure of subchondral bone and sclerosis (better score on the scale) than the control groups (I) (osteoarthritis without treatment), group (II) treated with commercial hyaluronic acid and hyaluronic acid with nanoparticles without drug (III).

ConclusionsThe use of active viscosupplements could have an additional effect to conventional hyaluronic acid treatment due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect. The most promising group was hyaluronic acid with nanoparticles that encapsulate curcumin and the second group was the one that encapsulates dexamethasone.

Evaluar con un modelo animal de osteoartrosis (conejos de raza Nueva Zelanda) la eficacia del tratamiento con viscosuplementos activos (ácido hialurónico [AH]) cargado con nanopartículas (NP) que encapsulan compuestos o fármacos antiinflamatorios.

Material y métodosEstudio experimental compuesto de cinco grupos de conejos a los que se realizó la sección del ligamento cruzado anterior (LCA) y resección del menisco interno para desencadenar cambios degenerativos y usarlo como modelo de osteoartrosis. Los grupos se dividieron en osteoartrosis sin tratamiento (I), tratamiento con AH comercial (II), tratamiento con AH con NP vacías (III), tratamiento con AH con NP que encapsulan dexametasona (IV) y tratamiento con AH con NP que encapsulan cúrcuma (V). En los grupos II a V se realizó la infiltración del compuesto correspondiente espaciándolas una semana.

Se realizó un análisis histológico macroscópico mediante una escala basada en la clasificación de Outerbridge para la artrosis.

ResultadosObservamos que dicho modelo de osteoartrosis es reproducible y se aprecian cambios degenerativos similares a los que se encuentran en el ser humano.

Los grupos a los que se infiltró AH con NP cargadas con curcumina (V), seguido del grupo de dexametasona (IV) presentaron macroscópicamente menos fibrilación, exposición de hueso subcondral y esclerosis (mejor puntuación en la escala) que los grupos de control (I) (osteoartrosis sin tratamiento), el grupo (II) tratado con AH comercial y el de AH con NP sin fármaco (III).

ConclusionesEl uso de viscosuplementos activos podría tener un efecto adicional al tratamiento convencional de AH por su efecto antioxidante y antiinflamatorio, siendo el grupo más prometedor el de las NP que encapsulan curcumina y en segundo lugar el de dexametasona.

Osteoarthritis is the most common chronic joint disease with currently few effective treatments in existence, and none of which have been shown to delay disease progression.

This disease may affect both minor and major joints, with the knee joint being the most affected in terms of both symptoms and radiological confirmation, affecting over 10% of men and 13% of women over 60 years of age.1

This disease is painful and has direct repercussions on patient mobility and autonomy in addition to being indirectly linked to other comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases and high blood pressure.

Osteoarthritis is the first cause of permanent disability and the third of temporary occupational disability, quite apart from its annual cost burden on the health system.2

Treatment of Osteoarthritis includes general, medical, and surgical therapies depending on disease evolution and progression.

General therapies include lifestyle changes, physiotherapy; symptomatic slow-acting drugs (SYSADOA); oral and topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); intra-articular injections with corticosteroids; hyaluronic acid (HA); platelet-rich plasma and mesenchymal stem cells.1,2

If previous treatments fail, surgery is used: joint lavage; subchondral perforations; osteotomies; cartilage grafts, or arthroplasties.

One of the most commonly used treatments before prosthetic replacement is exogenous HA injections which aim at restoring the compromised viscoelastic properties of the synovial fluid.1

In order to provide an additional benefit to the visco-supplementation effect currently applied in the clinic, the use of a viscosupplement that also contains polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) based on vitamin E that encapsulate different anti-inflammatory compounds or drugs (curcumin, celecoxib or dexamethasone) is proposed.3

Material and methodsPreparation of the active viscosupplements and NPsNPs are polymers derived from vitamin E, developed at the Institute of Polymer Science and Technology – Higher Council for Scientific Research (ICTP-CSIC for its initials in Spanish) in Madrid, which have the capacity to encapsulate different drugs.

Prior to our in vivo model, in vitro studies were carried out to form the active viscosupplements, assess cellular toxicity on cell cultures with macrophages and chondrocytes and finally to assess the injectability of NPs into subcutaneous tissue of the rat.3

The ICTP-CSIC group develop biomaterials for the biomedical sector and in particular polymers with application in tissue engineering, controlled release systems of bioactive compounds and polymeric drugs.

One of the studies focused on the addition of polymeric NPs based on vitamin E and loaded with different anti-inflammatory drugs, aimed at providing an additional benefit to the effect of the viscosupplement (HA), such as an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect.3–5

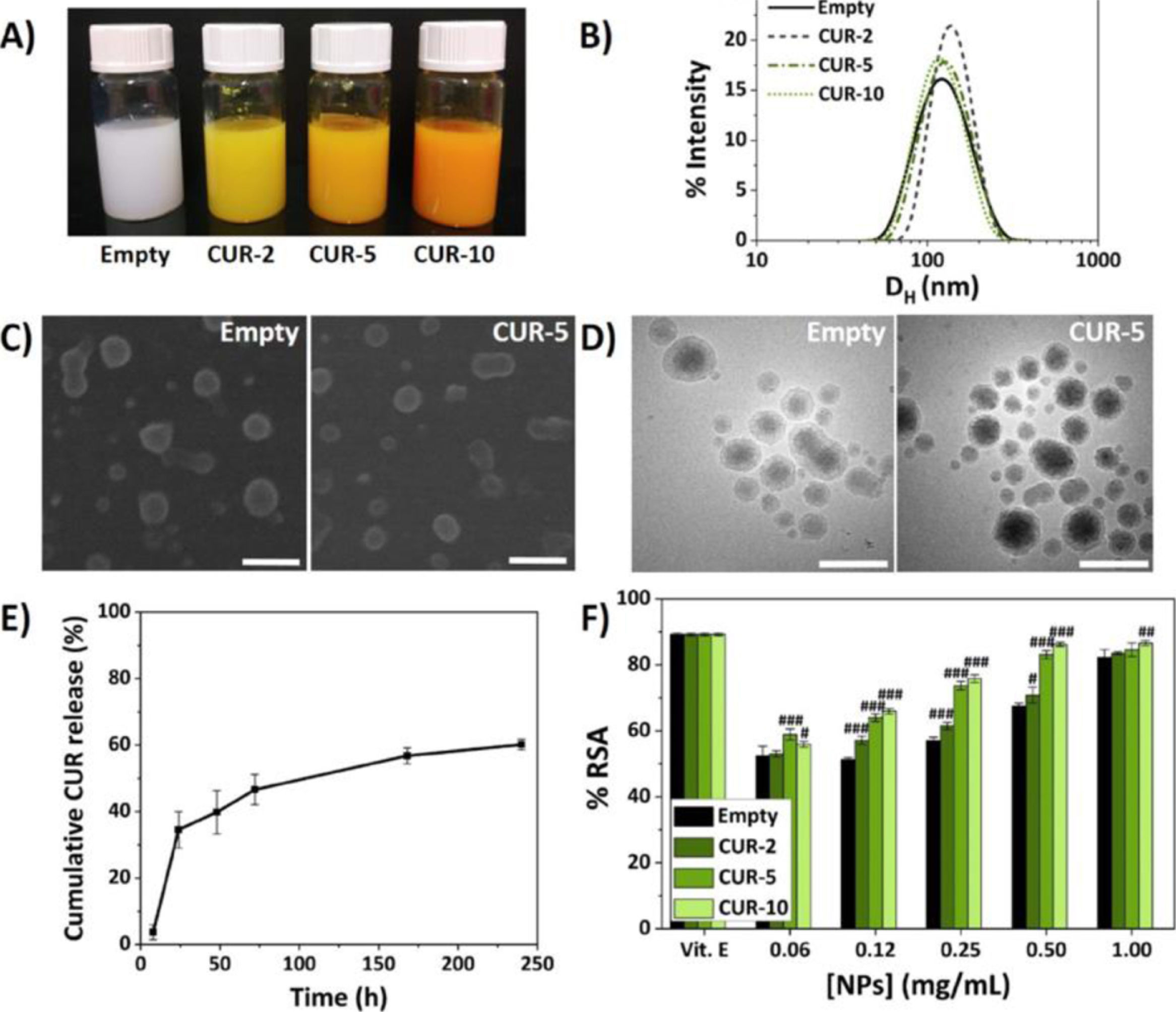

In vitro, the physicochemical properties of the NPs were synthesised and characterised to determine the formulations with their hydrodynamic diameters (Dh), polydispersity indices (PDI) and encapsulation efficiencies.

Fig. 1 shows the biocompatibility studies of the NPs that encapsulate curcumin.

Characterisation of the NPs.5

Cytotoxicity assays were also performed using the mouse macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 (Sigma-Aldrich) and human chondrocytes CH-a (INNOPROT) and assays for measuring the antioxidant effect by 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and anti-inflammatory by measuring nitric oxide (NO) in macrophages.3–5

Once the NPs were characterised, injectable polymeric formulations were designed by dissolving the high molecular weight HA in the previously prepared NP dispersions and cross-linking them with divinyl sulfone (DVS), achieving rheological properties in terms of viscosity (G′ and G″) very similar to or superior to two commercial viscosupplements (Adant® and Hyalone®).3–5

Animal modelThe rabbit animal model was chosen due to the anatomical similarity of its knee to that of a human, together with the availability and size of the joint.

The Animal Research Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines were followed, as well as the basic standards applicable to the protection of animals used in experiments and other scientific purposes, including teaching (R.D. 53/2013), in addition to the recommendations for the humane end point (Directive 63/2010/EU). Since this was a project on animals, the replacement, reduction and refinement methods were applied.

Before the start of the project, the training courses and procedures necessary to achieve the required training (A, B, C and D) were carried out according to R.D. 53/2013 (BOE 8 February 2013) and O. ECC 566/2015 (BOE 1 April 2015).

The project was also assessed by the hospital's animal ethics committee and received approval from the general directorate of agriculture, livestock and food (department of environment, land use and sustainability) with registration code ES280790000092.

Conducting the study with an animal model is essential to assess the macro and microscopic changes that occur with the use of this new therapeutic tool for osteoarthritis.

Furthermore, the Rabbit Grimace (RbtGs) pain scale was used based on five actions: orbital closure (0–2), cheek flattening (0–2), nose shape (0–2), moustache change and position (0–2), ear position and shape (0–2) during each of the procedures.6

The aim of the study was to assess and characterise the response of these new viscosupplements and their benefits in “in vivo” systems (New Zealand rabbits), after inducing osteoarthritis in them using the model called sectioning the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).7–9

Five groups of animals were included: group I Osteoarthritis without treatment (control group of two rabbits), group II (n=5) with commercial cross-linked HA (Adant®), group III (n=5) with cross-linked HA loaded with NP without drug (control group), group IV (n=5) with cross-linked HA loaded with NP encapsulating dexamethasone and group V (n=5) with cross-linked HA loaded with NP encapsulating curcumin.

Surgical procedureThe rabbits used were all females of the New Zealand race (San Bernardo farm, Navarra, Spain) 16 weeks old and weighing approximately 3.5kg. After a one-week acclimatisation period, they underwent a unilateral randomised section of the ACL, associated with internal meniscectomy through a medial parapatellar approach.

The instability created by the above procedure was confirmed.

The procedure was carried out in the operating rooms of the Ramón y Cajal Hospital animal facility, after a prior two-hour fast, under aseptic and antiseptic conditions, intraoperative antibiotic therapy, analgesia and anaesthetic sedation, as well as monitoring of vital signs.

InfiltrationsFrom the fourth week after surgery, intra-articular visco-supplementation was injected weekly in each of the corresponding groups (groups II–V) until two infiltrations were completed.

In groups III–V, where HA was injected with NP (empty, with dexamethasone and curcumin), both components were previously mixed in a proportion of 75% HA and 25% NP using a stopcock system and Luer lock syringes.

The infiltrations were performed under aseptic conditions with a 21 or 23G needle at the intra-articular level, with antero-external access after studying the anatomical references. The animals were allowed free movement in the cage and fed ad libitum.

Euthanasia was performed at 10 weeks, intravenously with lidocaine, Propofol and ClK.

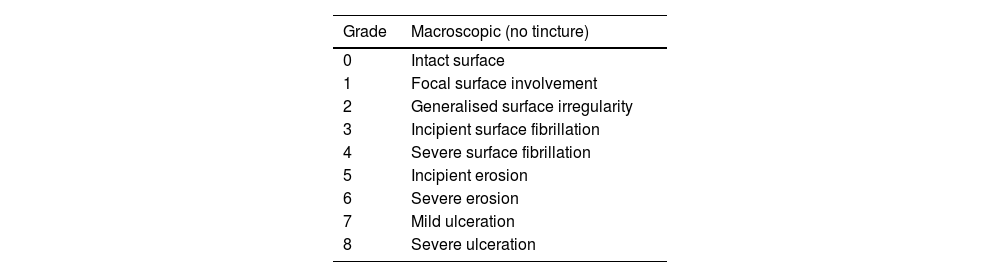

Macroscopic analysisThe four compartments of each knee were evaluated, medial, lateral, femoral condyles and tibial plateaus. The specimens were photographed with a high-resolution digital camera. Although quantitative methods exist, these systems are not frequently used because they require specific technology and are time-consuming. The results were evaluated according to the following classification, adapted from Outerbridge,9 which is contained in Table 1.

Macroscopic classification.9

| Grade | Macroscopic (no tincture) |

|---|---|

| 0 | Intact surface |

| 1 | Focal surface involvement |

| 2 | Generalised surface irregularity |

| 3 | Incipient surface fibrillation |

| 4 | Severe surface fibrillation |

| 5 | Incipient erosion |

| 6 | Severe erosion |

| 7 | Mild ulceration |

| 8 | Severe ulceration |

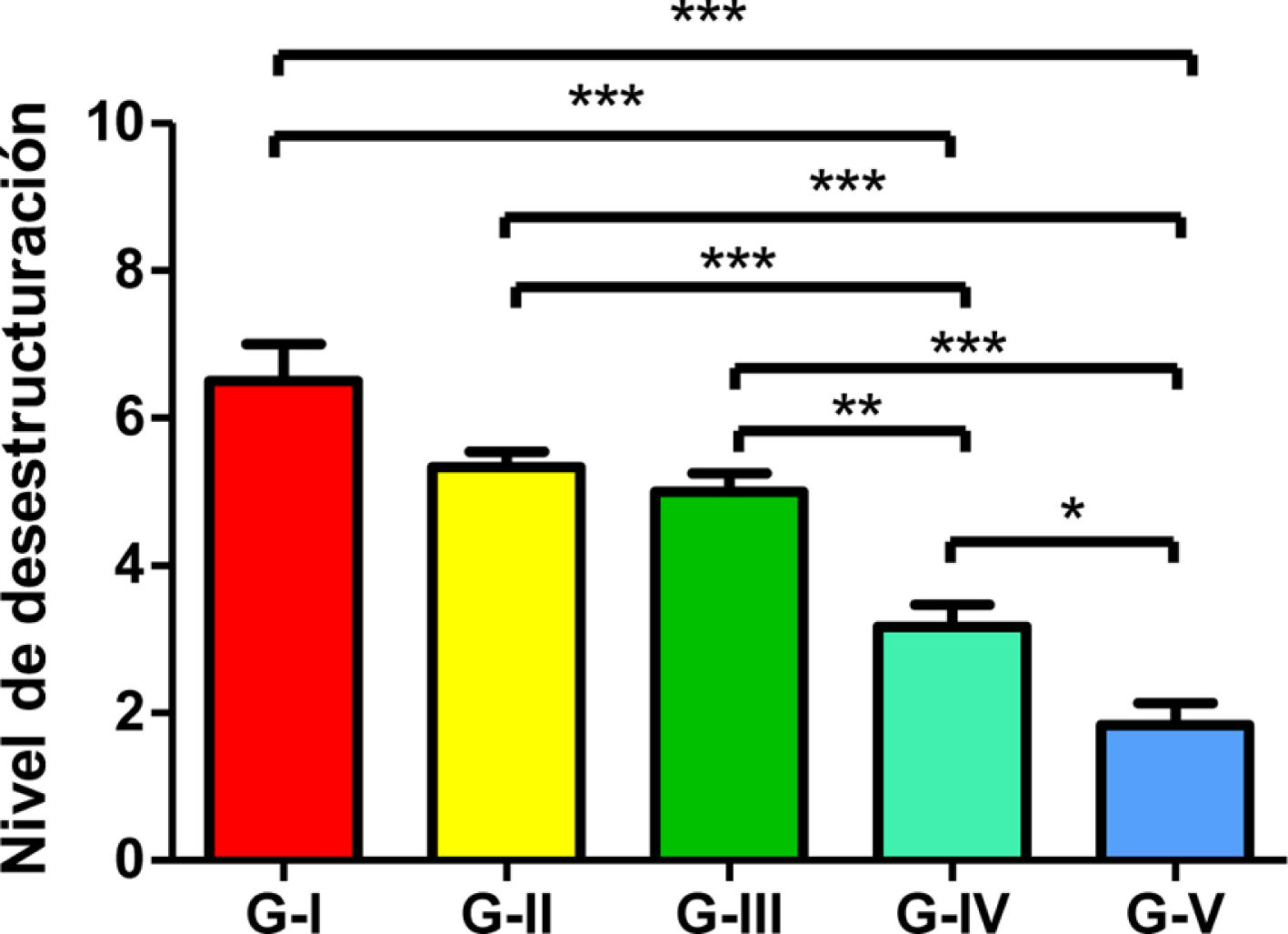

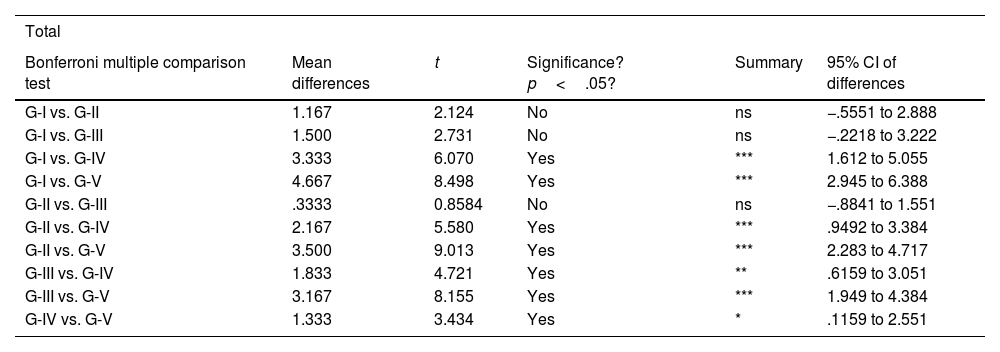

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism® v6.0 (GraphPad, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and a Bonferroni multiple comparison test was applied to compare both groups. Results were expressed as mean±SD. Significant values were set as p<.05 (comparison between groups IV and V), p<.01 (comparison between groups III and IV) and p<.001 (comparison between each group and the remaining groups).

ResultsClinical assessmentThe animals did not show clinical signs of poor pain control during the study. Pain was assessed using the Grimace scale from Newcastle University.

One of the rabbits died during the anaesthetic procedure before proceeding to the infiltrations (group IV), another presented septic arthritis (group II) and had to be euthanised. After the episode, aseptic and sterilisation measures were taken to ensure that the surgical material was kept in extreme conditions during the procedure.

Macroscopic outcomesThe assessment was carried out independently of the person who performed the surgeries and infiltrations, so that the groups and samples were only numbered and referenced (knee operated on in each animal) to avoid biasing the analysis.

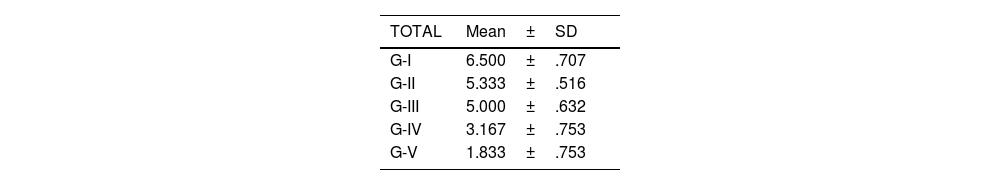

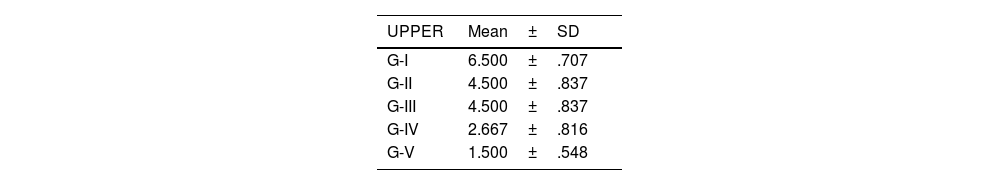

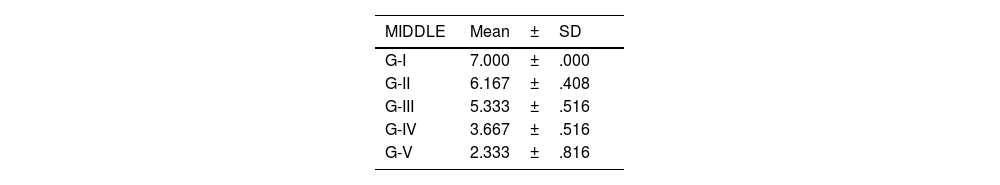

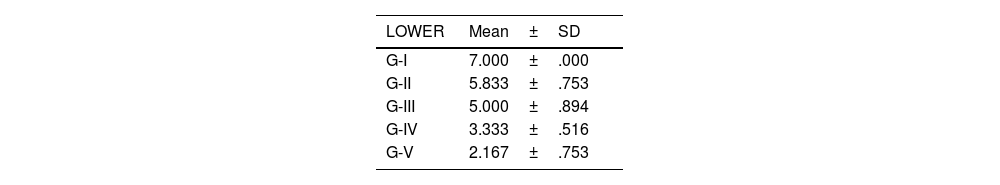

The level of joint destructuring was analysed in the different areas (upper, middle and lower) and also generally.

According to the adapted macroscopic classification of Outerbridge, greater joint involvement was observed in the four compartments of the untreated osteoarthritis group (I: control) and in the osteoarthritis group treated with HA with empty NP (group III) in a similar way to the osteoarthritis group treated with commercial HA (group II) (Fig. 2).

Knees treated with HA with NP containing curcumin and dexamethasone showed fewer degenerative changes, with less affectation in group V (curcumin) (Fig. 3) compared to group IV (dexamethasone).

There were no statistically significant differences between the group treated with commercial HA and HA with empty NPs (Fig. 4).

The results of these studies are shown in Tables 2–6, and Fig. 5.

Bonferroni multiple comparison statistical results.

| Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonferroni multiple comparison test | Mean differences | t | Significance? p<.05? | Summary | 95% CI of differences |

| G-I vs. G-II | 1.167 | 2.124 | No | ns | −.5551 to 2.888 |

| G-I vs. G-III | 1.500 | 2.731 | No | ns | −.2218 to 3.222 |

| G-I vs. G-IV | 3.333 | 6.070 | Yes | *** | 1.612 to 5.055 |

| G-I vs. G-V | 4.667 | 8.498 | Yes | *** | 2.945 to 6.388 |

| G-II vs. G-III | .3333 | 0.8584 | No | ns | −.8841 to 1.551 |

| G-II vs. G-IV | 2.167 | 5.580 | Yes | *** | .9492 to 3.384 |

| G-II vs. G-V | 3.500 | 9.013 | Yes | *** | 2.283 to 4.717 |

| G-III vs. G-IV | 1.833 | 4.721 | Yes | ** | .6159 to 3.051 |

| G-III vs. G-V | 3.167 | 8.155 | Yes | *** | 1.949 to 4.384 |

| G-IV vs. G-V | 1.333 | 3.434 | Yes | * | .1159 to 2.551 |

CI: confidence interval.

Level of total de-structuring. The asterisks refer to the comparisons made between the corresponding groups regarding the level of total destructuring (since a Bonferroni multiple analysis was performed). * Comparison between group IV and V. Significance level p<.05 applied. ** Between group III and IV. Significance level p<.01 applied. *** Between each group and the remaining ones. Significance level p<.001 (more demanding).

In vitro experimental models for osteoarthritis are much more controllable than animal models and are used to investigate short-term biological events, to deduce the mechanism of action, since fewer variables are produced and the results can be more discernible. However, these models cannot reproduce the structural changes that occur in tissues in the medium and long term.10

Experimental models allow us to carry out a sequential study of the disease, in this case osteoarthritis, to accurately determine the onset and duration of the disease, as well as its severity and progression over time. The scale and progression are reproduced in a controllable way, and the pathological changes found can be rigorously quantified and categorised with to develop new therapies.11

An alternative used in experimentation is the osteoarthritis model in rats, but they do not have a wide joint surface and this hinders the techniques to be performed.10,11

Other alternative methods of inducing osteoarthritis in animals are induction by chemical agents (papain, trypsin, collagenase) or mechanical or surgical manipulation: direct injury to the cartilage, misaligning osteotomy or immobilisation.

Meniscectomy for the induction of osteoarthritis is a surgical procedure that was described by Moskowitz et al. (1979), initially in rabbits. It has subsequently been associated with ligament section by other authors such as Kamekura (2005), Brandt KD (2002) and Bendele AM because the arthritic changes are faster and more extensive (four to six weeks).12–14

Several systematic reviews have demonstrated the positive effect of visco-supplementation as an analgesic treatment, although the efficacy of HA therapies remains controversial due to the inconsistency of treatment guidelines and current literature.15,16

Both in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated physiological effects of exogenous HA, such as chondroprotection and suppression of aggrecan degradation, which can counteract the mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. In addition, they can reduce the production of pro-inflammatory mediators and extracellular matrix metalloproteinases (MMP).17,18

The interaction of HA with the CD44 cell receptors inhibits the expression of IL-1β and consequently the production of MMP, disintegrin and metalloproteinase, zinc and calcium-dependent (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs, ADAMTS) and NO, responsible for joint destruction,19,20 Effects on the synthesis of proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, anti-inflammatory, analgesic and actions on subchondral bone have also been published.19

Intra-articular injection of viscosupplements is the best delivery route because they act locally on the affected joint. Here the aim is to achieve the maximum concentration of the drug in the required tissue.21 The analgesic action of HA must have a high durability to reduce the number of required infiltrations and reduce discomfort. Clinically, HA viscosupplements with high molecular weights and cross-linked appear to have better capabilities than simple and low molecular weight ones.15 There are different commercial formulations of HA on the market for intra-articular administration, which differ in their molecular weight, degree of cross-linking and origin, although there is currently no clear recommendation for one over the other.

One of the major problems with the intra-articular delivery route is the speed of drug distribution and clearance in the joint, due to the lymphatic system.21 A solution to the problem could be for viscosupplements to have a slow-release vehicle or transporter function for the drug whilst at the same time performing their inherent function to restore the viscoelastic properties of the synovial fluid.3,22

Drug-release systems have been studied and developed in recent years to increase drug bioavailability and reduce systemic effects, such as liposomes, microparticles and micelles.22

Previous studies on animal models have evaluated the use of polymers as a drug-release system bound to HA, including chitosan, polylactic-glycolic acid and cyclodextran, offering favourable results in terms of joint protection after treatment.23–25

There is evidence of the positive effect of curcumin on osteoarthritis, in animal models (mouse) in terms of mediation with inflammatory and chondroprotective factors.26

In this study, we demonstrated that the osteoarthritis model used, consisting of the section of the ACL associated with resection of the internal meniscus, reproduces the degenerative changes in a similar way to that which occurs in humans.

It is an in vivo model that causes instability and subsequent osteoarthritis in a much shorter time than would be necessary in humans, and is therefore very useful in terms of being able to influence the process through treatments like those of active viscosupplement infiltrations in our case.

With our animal model of osteoarthritis we were able to compare the effect of the infiltrations between the different treatment groups.

Based on the results obtained, we interpreted that there is a favourable effect in the treatment groups with HA loaded with NPs encapsulating curcumin and dexamethasone, with greater joint protection in the curcumin group (p<.05).

The effect of HA visco-supplementation would be an add on to the anti-inflammatory effect of the drugs, which would be progressively released intra-articularly through this system, in accordance with previous in vitro models.

A limitation of the study is the number of animals, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions, even though the number of animals was calculated according to previous series of other similar studies.

Lastly, it should be noted that extrapolation of results to humans is limited and should be viewed with precaution.

Future investigation will focus on the application of nanotechnology, aimed at reducing the necessary drug doses, and the use of targeted cell therapy in the early stages of osteoarthritis.

Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine is also a booming and promising field in the treatment of joint disease.27,28

Therapies such as hydrogels, which have exceptional physical and chemical properties, and the ability to transport and release bioactive agents, are positioned as possible specific treatments. The combination with therapies using growth factors and gene therapy, as well as hydrogels based on the response to physiological signals may offer more effective solutions.29

ConclusionsThe use of active viscosupplements could have an additional effect to conventional HA treatment due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect, with the most promising group being NPs encapsulating turmeric and secondly dexamethasone.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence i.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The SECOT Foundation for the 2020 research grant awarded.

Synthesis of HA cross-linked hydrogels at ICTP-CSIC (Polymer Science and Technology Institute. Higher Council for Scientific Research), with the collaboration of researchers Pontes, Aguilar, San Román and Vázquez.

Vets and animal house staff (technicians and attendants) at the Ramón y Cajal University Hospital, University of Alcalá de Henares.

Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology Residents at the Ramón y Cajal Hospital for their contribution and help during the project. In particular, Victor Casas, Salvador Álvarez and Hector Toribio.