En bloc resection of vertebral metastases has been the subject of study in medical literature due to its impact on patients’ quality of life and effectiveness in local disease control. This bibliographic analysis examines the findings and perspectives of published studies concerning en bloc resection of oligometastases in the spine. The technique, which involves the complete removal of the tumour along with a portion of the surrounding bone, has been shown to improve local tumour control, reduce recurrence, and potentially prolong patient survival compared to conventional decompression and stabilisation techniques. However, en bloc resection also presents risks and complications, such as surgical morbidity and extended recovery time. Appropriate patient selection, preoperative planning, and a multidisciplinary approach are essential to optimise outcomes. As new techniques and advances in adjuvant treatment develop, en bloc resection of oligometastases in the spine remains an area of interest in oncological research.

La resección en bloque de metástasis en la columna vertebral ha sido objeto de estudio en la literatura médica debido a su impacto en la calidad de vida de los pacientes y a su efectividad en el control local de la enfermedad. Este análisis bibliográfico examina los hallazgos y las perspectivas de estudios publicados en relación con la resección en bloque de oligometástasis vertebrales. La técnica, que implica la extirpación completa del tumor junto con una porción del hueso circundante, ha demostrado mejorar el control local del tumor, reducir la recurrencia y potencialmente prolongar la supervivencia de los pacientes en comparación con las técnicas convencionales de descompresión y estabilización. Sin embargo, la resección en bloque también presenta riesgos y complicaciones, como la morbilidad quirúrgica y el mayor tiempo de recuperación. La selección adecuada de pacientes, la planificación preoperatoria y el enfoque multidisciplinario son fundamentales para optimizar los resultados. A medida que se desarrollan nuevas técnicas y avances en el tratamiento adyuvante, la resección en bloque de oligometástasis vertebrales sigue siendo un área de interés en la investigación oncológica.

Solitary spinal metastases are a common complication in patients with advanced cancer. Treatment of these lesions may include different options of surgery, radiotherapy, systemic therapy, or a combination of these. Surgery, SBRT, and en bloc resection, in particular, are two common treatments for solitary spinal metastases. This trial will review the current evidence to determine which of these treatment options is most indicated for patients diagnosed with solitary spinal metastases.

TreatmentThe goals of treatment of spinal metastases are to relieve pain, improve, or reverse neurological compromise, correct spinal instability and deformity generated by vertebral collapse, ameliorate disease, if possible, with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy or surgery, and improve the patient's quality of life. As a multidisciplinary team treating these patients, we must be aware of the different treatments available to us:

- •

Steroids: help to improve acute neurological involvement, reducing peritumoural oedema and help to manage pain.

- •

Denosumab: bisphosphonates, in general, especially denosumab, are used to improve bone sufficiency in vertebral tumours; they produce calcification of the tumour mass and in some cases reduce it. They prevent osteoclastic bone resorption and reduce the risk of fracture.

- •

Radiotherapy: widely used in the treatment of vertebral metastases, useful in relieving pain in 80% of cases and reducing tumour volume in radiosensitive, slow-growing tumours without neurological involvement and without vertebral instability. Conventional palliative radiotherapy is limited by the inability to deliver large doses due to spinal cord toxicity. There have been significant advances and paradigm shifts in this aspect since the introduction of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) (SBRT), which allows the radiation of high doses of SRS, avoiding spinal cord toxicity, with proven precision, and eliminating the classic differentiation between more or less radiosensitive histologies. Separation surgery is important at this point, as it is a procedure by which the thecal sac is separated from the tumour by a few millimetres, allowing stereotactic radiosurgery to be safely administered.1–4

- •

Chemotherapy: increasingly more specific for target cells allowing targeted treatment with better results. It includes immunotherapy, hormone therapy, etc.

- •

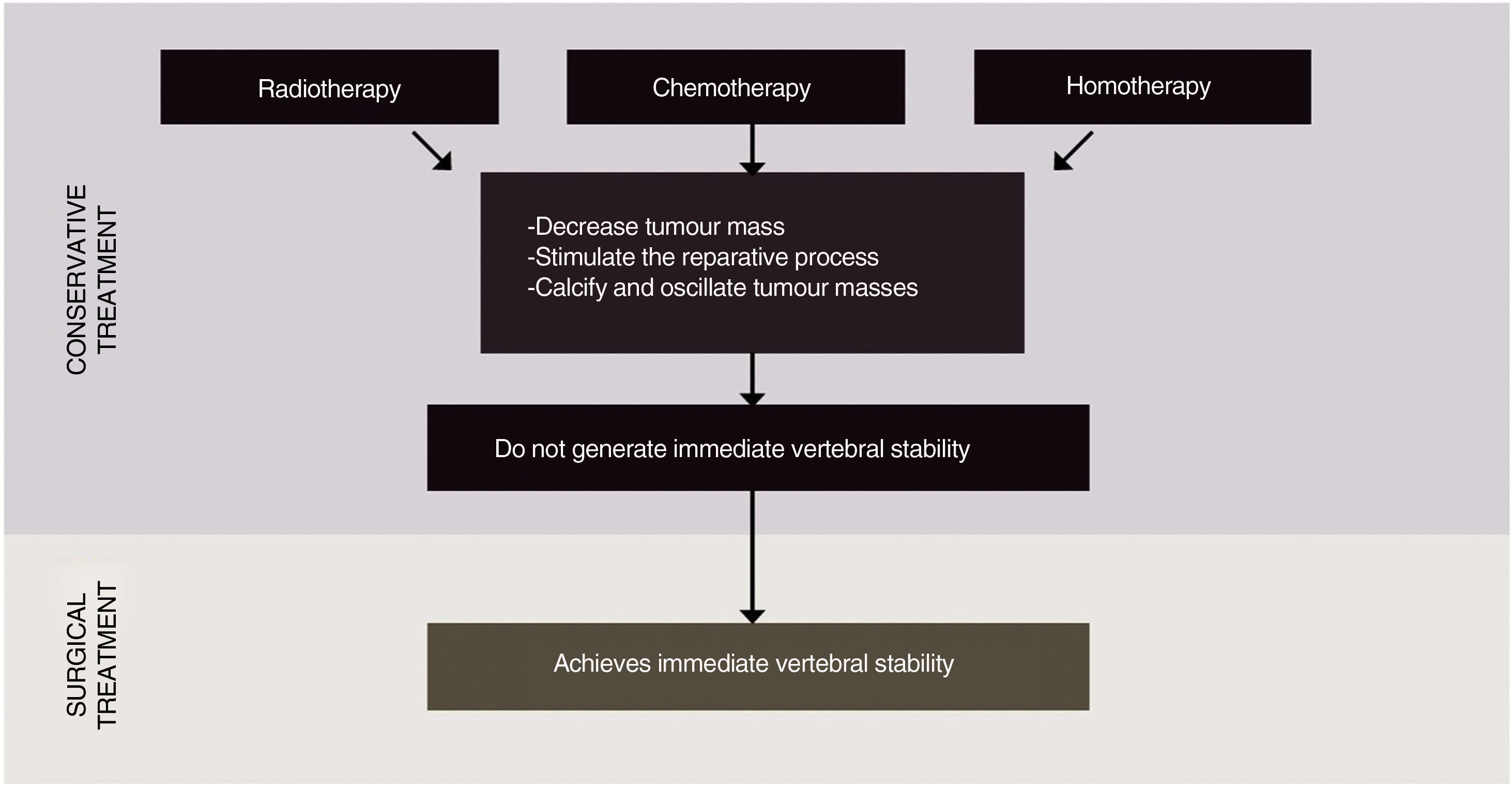

Surgical treatment: is the treatment of choice for intractable pain, progressive neurological involvement, tumour radioresistant to conventional radiotherapy, spinal instability, single or multiple bone metastases, poor response to radiotherapy or chemotherapy (Fig. 1).

All treatments for metastatic tumour disease are based on multidisciplinary management and include different therapies, each being fundamental to offer the best possible alternative to the patient. It should be borne in mind that only surgery is capable of generating immediate spinal stability for patients with progressive neurological compromise or spinal instability.

Historically, spinal oligometastases have been treated with invasive surgical approaches such as en bloc resection or conventional low-dose palliative external-beam radiotherapy (EBRT), or both. Unfortunately, en bloc resection, which is used to achieve clear surgical margins, results in substantial patient morbidity with local control, but without ensuring an optimal long-term overall disease outcome.5–7 Conventional EBRT improves pain in 60% of cases of patients with vertebral metastases, with a duration of less than 4 months.8,9 According to Spratt et al., as the number of patients with metastatic cancer surviving longer than 3 months increases, lasting palliative effect and long-term tumour control becomes necessary and they propose stereotactic spinal radiosurgery as an alternative therapeutic option.10

There is a paucity of literature to guide the management of vertebral metastases. Several frameworks have been developed that emphasise important concepts and decision points in the management of these metastases, such as Neurologic, Oncologic, Mechanical (stability), and Systemic disease [NOMS], and Location of disease in the spine (L), Mechanical instability (M), Neurology (N), Oncology (O), Patient fitness, Prognosis and response to Prior therapy (P) [LMNOP].11,12 All are intended to provide key principles and guidance to radiation oncologists and spine surgeons. These frameworks, to say the least, often simplify or omit important details that are fundamental to the management of patients with spinal metastases, a process that is often led by a medical oncologist, rather than a radiation oncologist or spine surgeon.

Surgical treatmentThe goal of surgery is to stabilise the mechanically unstable spine, decompress spinal cord compression, eliminate epidural disease to allow SRS and SBRT treatment of the spine, establish a histological diagnosis, and provide local control when radiotherapy cannot be administered.

The surgical procedure chosen should consider factors such as the mechanical stability of the spine, the patient's neurological status, previous adjuvant treatment, and the patient's preferences. Since radiotherapy is used in an attempt to eradicate the tumour, the surgical approach must be timed so as to administer effective postoperative radiotherapy.

Surgical treatment of metastatic disease is largely non-oncological, meaning that surgery alone will not eradicate the disease with lasting control. In one case series,13 the local recurrence rate was 96% at 4 years and there was no difference in survival between those who underwent en bloc or intralesional resection. The integration of spinal SRS into the standard treatment process is a paradigm shift from previous years in which extensive surgeries for total macroscopic resections were performed in an attempt to cure patients with metastatic disease. These invasive surgeries have fallen into disuse in institutions with multidisciplinary spine programmes due to high complication rates.14 In 2016 Boriani et al. published the use of stabilisation to treat spinal metastases adapted to the overall goals of treatment. They also insisted that these operations are not performed frequently in the world, and therefore it is imperative that the experience gained in specialised centres performing these treatments be reviewed. To date, only a few reports focusing on the complications and outcomes of en bloc resections of the spine have been published.14–17 Some focus on a specific area of resection, others on the spine itself, while others address complications related to surgical treatment of various pathologies such as metastatic chordoma and metastatic thyroid carcinoma.7,18–20

Other studies in the literature show that effective en bloc resection results in fewer local recurrences and improves prognosis in both primary and isolated vertebral metastases15,16,21–23 from renal and thyroid carcinoma.6,20,23

En bloc resections compared to intralesional resections report better local control of recurrence, 92.3% versus 72.2%.21

Before continuing with the discussion of en bloc resections for the treatment of vertebral metastases, it is important to know and review the terminology24,25:

- -

Intralesional excision: removal of tumour fragments, subcategorised into:

- ∘

Intracapsular: incomplete tumour removal where macroscopic or histological remnants remain within the tumour capsule.

- ∘

Extracapsular: complete resection of the entire tumour mass together with peripheral tissue (3–5mm or more of healthy peripheral tissue), but with opening of the lesion.

- ∘

- -

En bloc resection: removal of the entire tumour mass, including the margin of healthy tissue overlying the tumour. After histopathological evaluation of the resection, the specimen is subclassified as:

- ∘

Intralesional, if the tumour was breached, thus causing tumour spillage (contaminated spread).

- ∘

Marginal, if a thin layer of normal tissue covers the tumour without rupture of tumour tissue through the covering or capsule.

- ∘

Wide, if a thick layer of healthy peripheral tissue, a dense fibrous covering (fascia), or a still infiltrated anatomical barrier (pleura), completely covered the tumour.

- ∘

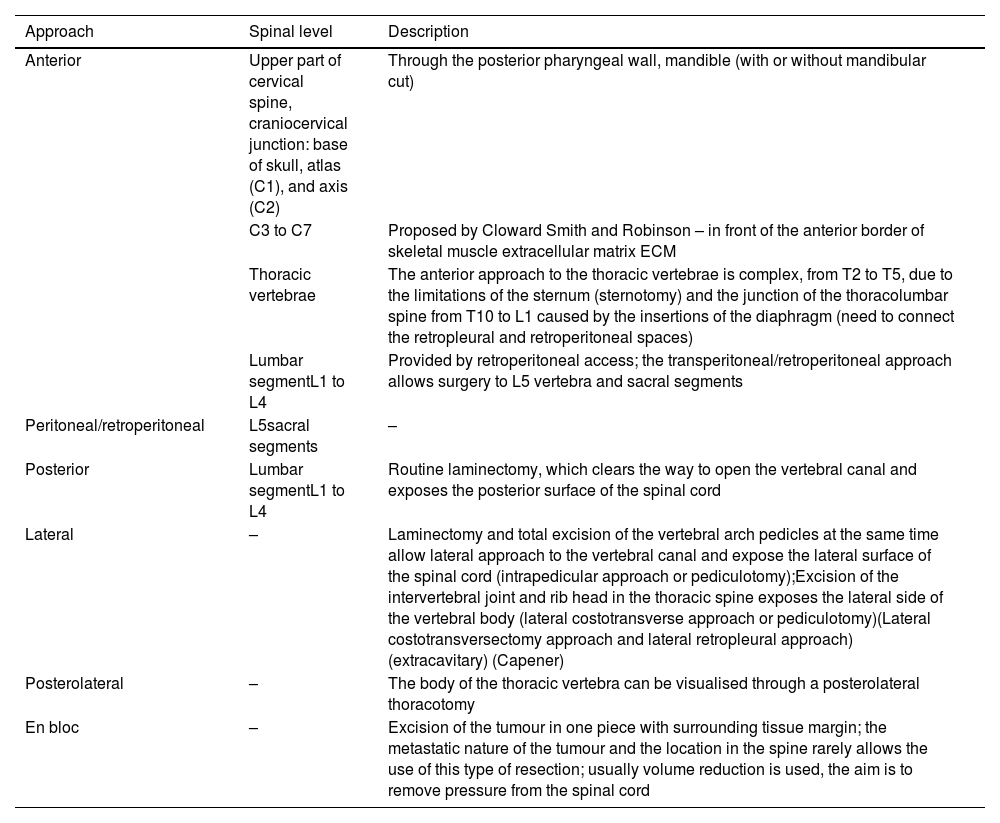

Surgical planning of en bloc resection is based on 7 different approach strategies that combine with each other: anterior, posterior, anterior followed by posterior, posterior followed by anterior and posterior, lateral, peritoneal, and en bloc (Table 1).26–33

Surgical treatment, approach.

| Approach | Spinal level | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior | Upper part of cervical spine, craniocervical junction: base of skull, atlas (C1), and axis (C2) | Through the posterior pharyngeal wall, mandible (with or without mandibular cut) |

| C3 to C7 | Proposed by Cloward Smith and Robinson – in front of the anterior border of skeletal muscle extracellular matrix ECM | |

| Thoracic vertebrae | The anterior approach to the thoracic vertebrae is complex, from T2 to T5, due to the limitations of the sternum (sternotomy) and the junction of the thoracolumbar spine from T10 to L1 caused by the insertions of the diaphragm (need to connect the retropleural and retroperitoneal spaces) | |

| Lumbar segmentL1 to L4 | Provided by retroperitoneal access; the transperitoneal/retroperitoneal approach allows surgery to L5 vertebra and sacral segments | |

| Peritoneal/retroperitoneal | L5sacral segments | – |

| Posterior | Lumbar segmentL1 to L4 | Routine laminectomy, which clears the way to open the vertebral canal and exposes the posterior surface of the spinal cord |

| Lateral | – | Laminectomy and total excision of the vertebral arch pedicles at the same time allow lateral approach to the vertebral canal and expose the lateral surface of the spinal cord (intrapedicular approach or pediculotomy);Excision of the intervertebral joint and rib head in the thoracic spine exposes the lateral side of the vertebral body (lateral costotransverse approach or pediculotomy)(Lateral costotransversectomy approach and lateral retropleural approach) (extracavitary) (Capener) |

| Posterolateral | – | The body of the thoracic vertebra can be visualised through a posterolateral thoracotomy |

| En bloc | – | Excision of the tumour in one piece with surrounding tissue margin; the metastatic nature of the tumour and the location in the spine rarely allows the use of this type of resection; usually volume reduction is used, the aim is to remove pressure from the spinal cord |

Preoperative planning is based on WBB staging,24 Tomita score,7 and Enneking's criteria,25 to achieve the required oncological margin with the least possible morbidity. Prognosis can be improved with more information, therefore other systems should be known in the surgical decision-making guide, such as Sioutos,34 van der Linden,35 Bauer,36 and Tokuhashi.37

The main parameters, on which all the literature with level of evidence I agrees,7,38,39 for estimating prognosis are:

- -

Preoperative ambulatory capacity.

- -

Karnosfky's functional status.

- -

Prior radiotherapy.

- -

The type of primary cancer.

- -

The presence of extraspinal metastases.

- -

The number of segments with vertebral metastases.

- -

Presence of pain.

- -

Body mass index.

The surgical parameters to consider are:

- -

Visual control, essential to achieve the target margin.

- -

The important anatomical structures should be freed or resected under visual control.

- -

Simultaneous combined approaches are associated with increased morbidity and should be performed only when essential.

- -

Spinal vascularisation should be considered in multi-segmental resection.

- -

Epidural bleeding can become a serious problem if underestimated.

- -

Removal of the specimen (lesion/tumour/tumour piece) should be planned with the best approach to avoid traction or twisting of the cord.

The steps proposed for surgical planning are:

- -

Oncological staging of the suggested margins.

- -

Define the functional implications of the margins with respect to the anatomical features.

- -

Review of tumour extent.

Diagnosis and staging are related to the aggressiveness of the tumour. The 1997 WBB, Weinstein–Boriani–Biagini, staging system24 suggests the precise surgical margin. If the tumour is growing in the epidural space (E-layer), the dura mater is considered the tumour boundary, its inclusion is assessed depending on the histology of the primary.40 When planning the approach, the spine surgeon must take into account that the epidural space is extracompartmental, and the dura would be expected to cover the tumour only if the epidural space is occupied by a scar, as in cases of recurrence. In a tumour that has never been operated on, extension into the epidural space can presumably be considered contamination of the entire space from the skull to the sacrum. In this situation, surgery should not be recommended as it leads to increased morbidity, and there is no evidence to suggest that en bloc resection would prevent recurrence, these details are not specifically included in the literature.

In the case where a wide resection margin is required due to tumour histology, but the margin involves a structure of some functional relevance that must be sacrificed, the decision-making process should include a cost/benefit discussion. If the tumour is growing around the nerve root, sacrifice of the nerve root should be considered. If the patient refuses such a surgical step, then violating the tumour should be considered.

The patient should be fully informed of the risk of this strategy with reference to local control and final outcome, and adjuvant therapy is indicated.

Obviously, this careful planning becomes more important the greater the number of extraspinal structures involved, such as major vessels, lung, ureter. The concept guiding the planning will always be the ratio between appropriate surgery (based on oncological criteria) and related morbidity. If surgery is appropriate based on evidence that local control can be achieved with a greater likelihood of a better outcome, then the option of functional sacrifice or increased risk of surgical morbidity should be discussed with the patient.

Tumour violation can occur during surgery if the surgeon inadvertently ruptures or opens the tumour.

Even after the most careful planning, tumour violation can occur unexpectedly, because visualisation of the tumour on preoperative imaging may be complete.

The extent of the tumour determines the surgical planning. If the tumour is growing anteriorly into the mediastinum, an anterior approach will be required to visualise the tumour and leave a layer of healthy tissue around it as a margin. The pleura is considered an appropriate margin and can be resected over the tumour by posterior approach only, even thoracoscopically.

A uniquely posterior approach, as per the Roy-Camille41 and Tomita39 techniques, may or may not provide such a margin, as digital dissection could violate the anterior aspect of the tumour. Only in some cases, the visual control provided by the anterior approach may allow resection with a safe margin.

Because the ultimate goal of en bloc resection is to improve local control of the disease, improving survival, this must be planned must be prior to surgery to achieve structural stability of the spine after resection, which requires circumferential arthrodesis.16,42–44 Implants, autologous grafts, or bone substitutes and various osteogenic induction materials are used to achieve fusion of the spinal arthrodesis at the resected level.

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy may adversely affect the possibility of achieving this fusion. The reconstructive technique used in most cases includes pedicle screws and posterior rods, as well as an anterior spine reconstruction (construct) with a mesh, prosthesis, filled with biological bone.16 In Boriani and Gasbarini's study of en bloc resections in 220 patients, fusion failure occurred in 14% of patients, but was clinically significant in only 9 cases, 4%, and required revision surgery. There was no revision surgery for anterior spine failure. Posterior fusion failures occurred in the late postoperative period.5

The results in terms of better prognosis and better local disease control justify such demanding and rigorous procedures in aggressive benign and low-grade malignant bone tumours and some vertebral metastases, and en bloc resection has the best results.6,15,16,19,21–23,39–41,43,45–50 The surgeon who treats the patient first has a great responsibility, because it is the first treatment that has the greatest influence on prognosis. To reduce the possibility of local recurrence, morbidity, and mortality, an experienced, multidisciplinary team should be in charge of patient management.

What does the literature say about en bloc resection in spinal metastasis?Oliveira et al.51 in 2015 recorded the variety of surgical methods available for the treatment of spinal metastases. They suggested that for patients with a solitary spinal metastasis without spinal canal invasion, in good general health, and with long life expectancy, tumour resection by en bloc spondylectomy/total vertebrectomy with stabilising instrumentation is most recommended.

While it is true that candidates for en bloc spondylectomy are not frequently encountered,51–53 the published studies are biased by patients, technique, complications, …

In all scenarios of vertebral metastases, radiotherapy is a valuable tool to treat disease and control emboligenic foci. Radiosurgery is effective as a primary or adjunctive treatment for metastatic spinal tumours. Embolisation techniques help to control intraoperative bleeding.54–59

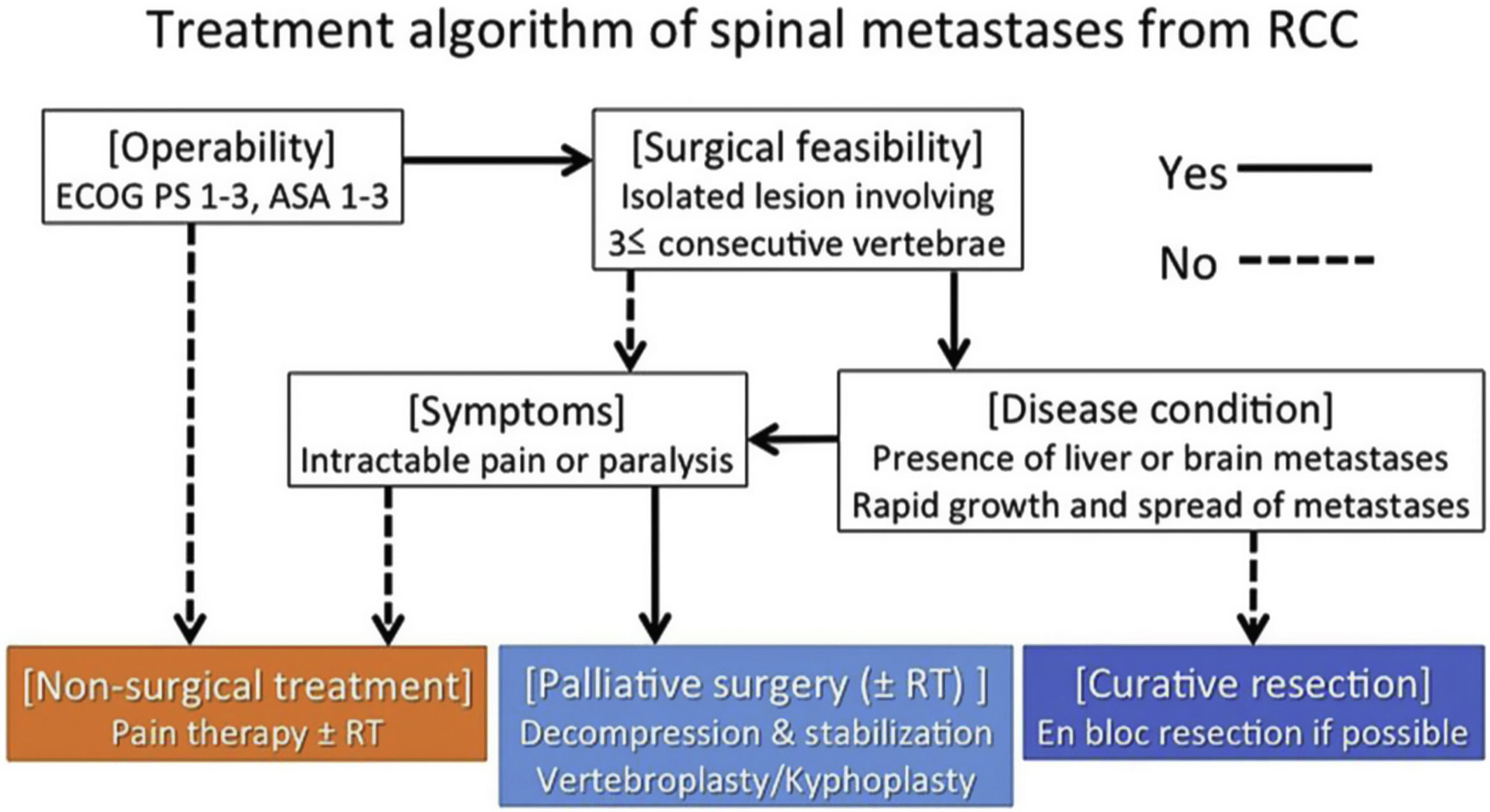

Professor Jaipanya's study group60 works with the NOMS framework11 for guidance in the comprehensive assessment of patients with spinal metastases. They propose in patients presenting with high-grade spinal cord compression and/or myelopathy with radiosensitive cancer, the administration of conventional external-beam radiotherapy, and these patients may be offered prior vertebral decompression surgery to optimise neurological outcome (separation surgery). In radioresistant tumours with high-grade spinal cord compression and/or myelopathy, they recommend vertebral stabilisation and decompression followed by spinal SRS. The group recommends en bloc resection for patients with life expectancy greater than 2 years with solitary metastases, supported by Kato et al.61 The latter argue that en bloc resection spine surgery has lost popularity due to high perioperative morbidity and high surgical complexity and has been replaced by hybrid therapy. There is an indication for en bloc spondylectomy in patients with an expected survival of more than 2 years, a solitary or primary controlled metastatic tumour without extraspinal metastases, preserved cardiovascular condition, and fit for surgery, with an acceptable preoperative status (ECOG-2), and in patients treated in centres without SRS in metastases with known resistance to cERBT.

To date, the literature review supports that the ideal candidate for en bloc surgery is a patient with a solitary metastasis that can be completely resected. It is the surgery of choice, especially in single metastatic lesions of renal cell carcinoma, and is performed via complete fragment excision in the cervical spine and en bloc total spondylectomy in the thoracic or lumbar spine.

The outcome of en bloc spine surgery is excellent, when it meets all the conditions defined so far, with a local recurrence rate ranging from 1.1% to 15.3%.61 In cases where complete tumour resection is achieved, superior local control and postoperative survival is expected compared to cytoreductive surgery, including reduction of the tumour in the anterior spine and decompression of the posterior elements. However, the rate of major perioperative complications is up to 39.7% and the perioperative mortality rate ranges from 1.3% to 9.77%.

En bloc resection for patients with isolated spinal metastases from thyroid cancer has also been reported with successful results.61 In a series of 8 patients, at the end of follow-up (mean 6.4 years), all patients were alive and five had no evidence of disease.

Although the focus on en bloc resection for renal cell carcinoma and isolated thyroid metastases has been emphasised, other histologies may be candidates if certain factors are met. Patients with oligometastases of breast cancer or a functional secreting metastasis (pheochromocytoma) may be indicated on a risk/benefit basis. However, the decision to proceed with en bloc resection should be multidisciplinary, considering all possible treatments and patient preferences.

In a carefully selected, restricted subgroup of patients with spinal metastases, it was suggested that these oncological or “en bloc” resections could improve local control and potentially lead to cure even in the presence of a bony metastasis to the spine; however, selecting the right patient remained a challenge. In addition, advances in the field of stereotactic spinal radiotherapy provided another option to treatment algorithms, reporting good local control rates without the morbidity associated with en bloc resections.2,3

En bloc resection is a procedure in which the tumour is removed without transgressing the tumour capsule, with the oncological goal of decreasing the risk of local recurrence and improving disease-free survival. The specimen obtained after histological study should provide information on the margins obtained. If the margin is wide, we refer to a wide margin, and if it is the tumour's own pseudocapsule, such as the dura mater, it is a marginal margin. Any voluntary or involuntary opening will make the procedure intralesional. This approach shows better local control and survival.4,6,9,14,39

The indications for en bloc resections are for patients with solitary or limited metastases for cure or prolonged local control. With advances in radiation oncology, specifically the widespread use of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), improved and more prolonged local control is commonly observed.10,11 This, along with the evolution of systemic targeted therapy, has made the indications for en bloc resection in the metastatic spine population even more difficult to standardise.

En bloc spondylectomy has generally been reserved for patients with a solitary metastasis and specific histology. Selecting the right patient for this type of surgery is a challenge because the prognosis is difficult to predict. The Tomita and modified Tokuhashi scores,7,37 are classification systems that have been widely used, criticisms have been raised, and their validity and reliability have been questioned.13–17 Furthermore, the inability to differentiate good and moderate prognosis using these scores has been reported.15 These scoring systems do not consider recent advances in the cancer field, such as molecular targeted therapies and SBRT.

Life expectancy has changed over the last decade for some tumours, especially patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC), whose survival improved between 2005 and 2010, due to more up-to-date treatments.18 The histology of the tumour, the functional status of the patient and the systemic burden of disease will guide the surgeon within the multidisciplinary group in the decision-making process. Thus, for an en bloc procedure to be considered, an oligometastasis of a histology with a favourable long-term prognosis must be present.

The introduction and spread of SBRT led to a significant change in clinical practice with respect to spinal metastases; tumours that were previously radioresistant are now radiosensitive due to the higher doses of conformal radiation that can be safely delivered. In a systematic review published in 2009,62 Bilsky reported that local control rates after en bloc resection compared to SBRT were similar. After en bloc resection, a local recurrence rate of 7.5% was observed at a median follow-up of 16 months. For SBRT, failure of radiological control or symptomatic progression ranged from 6% to 13% at a comparable median follow-up. Recently, however, current local control after SBRT for renal carcinoma has been reported to be 82% at 1 year and 68% at 2 years. Current overall survival at 1 year was 79% and decreased to 49% at 2 years.63

Boriani et al. published an article in which 25 patients were treated using the en bloc procedure for a solitary metastasis. In 52% of these patients, disease progression or death occurred at 8–20 months (32% mortality at 8 months), underlining our inability to select long-term survivors in whom local control would have been beneficial if en bloc resection had been performed.64 Based on these data, the Spine Oncology Study Group (SOSG) recommended that an isolated renal cell carcinoma metastasis without epidural compression should undergo SBRT as first-line treatment instead of en bloc resection (strong recommendation). If there is local recurrence after SBRT and the patient is doing well with no other metastases, en bloc resection may be considered because of the potential for long-term survival. To be eligible for SBRT, epidural disease must be minimal in order to maximise the dose and avoid spinal toxicity. Local recurrence usually occurs in the epidural space as a consequence of infradosification.35 After SBRT, higher failure rates were observed with grade 2 and 3 ESCC due to progression in the epidural space.58 Another prerequisite is that the metastatic lesion must be stable, as SBRT does not address mechanical instability. The SINS scale is useful in its assessment.65

Although the focus has been on en bloc resection for RCC and isolated thyroid spinal metastases, other histologies may be candidates if certain factors are present. Treatment of isolated spinal metastases from thyroid cancer has also been reported with good results.10 In a series of eight patients, at the end of follow-up (average 6.4 years).10 In patients with oligometastases from breast cancer or a functional secreting metastasis (e.g., pheochromocytoma) en bloc may be indicated on a risk/benefit basis. However, the decision to proceed with en bloc resection should be multidisciplinary, considering all possible treatments and patient preferences.

Patients selected for an en bloc procedure of the metastatic spine generally have fewer comorbidities than the general population. En bloc resection itself carries significant morbidity. Most en bloc resection studies included both primary and metastatic spinal tumours, because this procedure is unusual. The overall complication rate for a mobile location ranged from 13% to 73.4% and complication-related death ranged from 0% to 7.7%.14,27,30 The team's experience with this type of procedure is critical in reducing the complication rate. Amendola et al.15 reported that hardware failure requiring revision was 9.7%. The largest series on en bloc resection has recently been published and reports on 220 patients (primary and oligometastatic bone tumour).5 We believe that analysis of reconstruction would explain these figures as well as the systems used for reconstruction. The combined approach, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and radiotherapy were associated with adverse events.

The impact of an oncological resection on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) should be acceptable to the patient, especially in the metastatic spine population where life expectancy is generally reduced. Acceptable oncological outcomes can be obtained after en bloc resection for solitary spinal metastases. However, knowledge about patient-reported outcomes after this type of procedure is lacking. Selecting the right patient, for the right operation, is critical. Adequate HRQoL can probably be achieved with careful patient selection by a multidisciplinary team and an experienced specialised centre.

Goodwin et al., 2016,66 conducted a review of both patients and the literature, including patients with isolated metastases of secreting tumours (pheochromocytomas, carcinoid tumours, choriocarcinoma, etc.). En bloc resection resulted in cure of the metabolic situation, as well as a decrease in symptoms, and was the ideal treatment for them as it avoided local recurrence and systemic effects. The authors pointed out that en bloc resection prevents the complications of intraoperative hypertensive crisis frequently associated with intralesionally treated pheochromocytoma. They report that en bloc resection appears to be a potential surgical option for treating vertebral metastases. This technique is able to control tumour-induced sequelae, thus offering long-term local tumour control.15,18,22,24

According to the McDonnell classification, major complications may include pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, respiratory failure requiring tracheostomy, infection, hardware failure, paraplegia, haematomas, myocardial infarction, aortic or other vascular lesions, deep vein thrombosis, bowel injury, and death. Minor complications include superficial wound necrosis, durotomy, pseudomeningocele, minor vascular injuries, peritoneal injuries, haematomas, retrograde ejaculation, kyphoscoliosis, respiratory failure, or reactive pleurisy. The highest complication rates are associated with patients with tumour recurrence after intralesional excision or contamination of the epidural space or a major body cavity (50% in some series).27,38

In another study by Goodwin,67 negative expression of receptors (HER2 and ER/PR) is associated with shorter survival, short DFI (<24 months), and a high degree of axillary lymph node invasion in breast cancer are associated with poor survival.

Historically spinal metastases have been treated with invasive surgical approaches (e.g., en bloc resection), conventional low-dose palliative external-beam radiotherapy (EBRT), or both. Unfortunately, en bloc resection, which is used to achieve clear surgical margins, results in substantial patient morbidity and poor long-term local control.5,7,8

These types of invasive surgery have greatly decreased in number and indications in institutions with multidisciplinary spinal programmes due to their high complication rates, and we do not recommend en bloc resection as palliative treatment in patients with multiple spinal metastases.14,68

This study by Bandeira et al.,69 argue that en bloc resection of primary spinal tumours or metastatic lesions is a challenging procedure that correlates with a high complication rate and should therefore be performed by specialised surgeons. In the multidisciplinary management of spinal tumours, it is important to improve the integration of surgery and other treatments, focussing on timing and correct planning, to reduce risks and maximise the efficacy of each treatment.

Despite all the risks, these findings confirm that en bloc resection remains the gold standard surgical procedure for selected patients to achieve better survival rates and better local disease control.

In this 2019 study,70 it is stated that the prognosis of metastatic lesions after en bloc resection varies widely depending on the primary pathology and systemic disease status. They performed a review in this population where they estimated disease-free survival at 1, 5, and 10 years was 61.8%, 37.5%, and 0%, respectively. Overall survival for this cohort was not defined, but other studies have estimated median survival to range from 15 to 27 months. Local recurrence rates after en bloc resection for metastases have been reported to be low at 11%.

This same study states that for both primary and metastatic lesions, previous radiotherapy was identified as a risk factor for local recurrence. This might have been due to radiation-related changes in the peritumoural tissue, resulting in indiscriminate tumour boundaries. Intraoperative dural tear and tumour occupancy rate >50% of the spinal canal also predicted future local recurrence.

They reported that recurrence rates were higher in cases of reoperation and if performed in a non-tertiary centre.15,45

Overall, en bloc resection involves a higher complication rate compared to intralesional resection. Institutions that have started performing en bloc resections report complication rates of up to 76%,23 highlighting the importance of the surgeon's comfort when performing this procedure. They show that several operative factors affect the complication rate. The combined anteroposterior approach independently increases the incidence of major and minor complications compared to a posterior-only approach. This finding is not surprising given the likelihood of using a combined procedure in cases with more complex anatomical difficulty, increased associated blood loss, and increased morbidity. Prior surgery or open biopsy also appears to confer an increased risk of major complications as defined by the McDonnell classification. Prior radiotherapy increases infection rates, but not the overall complication rate. A higher number of levels also increases the risk of complications, and logically a further procedure.

Metastatic tumours of the spine (aetiological considerations)Spinal metastases are the most common type of spinal tumour and occur 20 times more frequently than primary spinal neoplasms.47 The spine is the most common site of skeletal metastases, and axial skeletal lesions account for approximately 39% of all bone metastases.27 Spinal cord compression secondary to spinal metastases occurs in 5%–10% of all cancer patients and in up to 40% of patients with existing non-spinal bone metastases.48 Subsequently, spinal metastases are a major source of pain and disability, and a potential opportunity for surgical intervention and improvement of quality of life. Despite the prevalence of spinal metastases, there is a paucity of data evaluating the efficacy of en bloc resection in this patient population.

Breast, prostate, and lung cancers are classically the most common primary tumours with a propensity to metastasise to the bony spine.49 En bloc resection has been reported to be an appropriate surgical option with adequate patient selection and favourable systemic disease status.13–15,50 However, the systemic burden of oncological disease often determines morbidity and mortality in this population. Therefore, the benefits of an aggressive en bloc resection procedure may not always outweigh the risks, and it is imperative to consider all patient characteristics to determine the optimal extent of resection.

A recent analysis of 91 patients who underwent en bloc resection for metastatic spinal lesions demonstrated a local recurrence rate of 11%, with a median follow-up duration of 27.4 months (range, 4–66 months).16 A history of prior radiotherapy (p=.04), intraoperative dural tear (p=.03), and a tumour occupancy rate of >50% of the spinal canal (p=.02) were found to predict future local recurrence. Sakaura et al.6 studied twelve patients who underwent en bloc resection of solitary thoracic metastases. En bloc resection provided long-term control for several patients within their cohort, with seven patients surviving for an average of 61 months.10 Similarly, Huang et al.17 recently reported the results of nine en bloc resections for solitary lumbar spine metastases.51 Five patients remained disease-free at the time of the most recent follow-up (mean follow-up 41.2 months). Another analysis showed that the median survival after en bloc resection is 15 months for patients with metastatic lesions, compared to 47.6 months in patients with primary spinal tumours.23 The benefits of en bloc resection, therefore, may be less dramatic in a metastatic population, but are not negligible.

En bloc resection may be of particular benefit to patients with radioresistant metastases. Renal, hepatocellular, colon, thyroid and non-small cell lung carcinomas, and melanoma are classically considered less sensitive to radiotherapy.52 Even in an era of increasingly precise radiosurgery, the epidural space and spinal cord are important dose-limiting structures, and therapeutic doses for these tumour types may not be achievable in the spine. Without radiation as a useful adjunct for these lesions, en bloc resection may offer a better chance of local control than a more conservative resection. Previous case series have described successful en bloc removal of renal cell, non-small cell, thyroid, and hepatocellular carcinomas.24,53–56

In the study by Satoshi, Murakami and Demura,71 patients in the complete excision group survived significantly longer than those in the incomplete excision group (5-year survival: 84% vs. 50%; 10-year survival: 52% vs. 8%). The results suggest considering complete surgical resection of vertebral metastases from thyroid carcinoma, even in patients with coexistent pulmonary metastases. Complete removal of spinal tumours, TES (total en bloc spondylectomy), is a complex and technically demanding surgery for spine surgeons. The experience of Satoshi's group cannot be extended to all surgical centres, and therefore they recommend that this surgery be performed in centres specialising in spinal tumours and by highly experienced surgeons.

The results of the study by the Lador and Gasbarrini working group72 showed that patients treated with complete excision survived significantly longer than those in the incomplete excision group, and that all long-term survivors in the incomplete excision group had tumour recurrence with consequent deterioration of performance status. Therefore, complete surgical resection of solitary spinal metastases is feasible and has the potential to maintain performance status and prolong survival.

The article by Satoshi, Murakami and Demura in 2016,73 remarked that spinal metastasis is considered a negative predictor of overall survival due to the difficulty of surgical resection.

Improved surgical techniques together with preoperative embolisation in the last two decades have achieved excellent clinical outcomes, with low morbidity.

Up to the date of the study in 2016, there had been no study evaluating the clinical outcomes of curative surgical resection in vertebral metastases from renal cell carcinomas. This study aimed to examine the survival of patients who underwent this procedure for this disease, in order to propose an effective treatment strategy based on an analysis of potential prognostic factors.

Thirty-six patients (26 men and 10 women) with a mean age of 58.6 years were included. Surgical indications for metastasectomy of spinal lesions were based on the following criteria: solitary spinal metastasis, surgical feasibility (tumour involved 3 consecutive spinal levels), operability (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG PS] Performance Status 3), and stable disease without other metastases or with a limited number of metastases. Eighteen patients, 50%, had spinal metastases when the primary renal cell carcinoma was diagnosed or were within the first year following diagnosis (synchronous metastasis). The median disease-free interval between primary kidney resection and diagnosis of spinal metastases was 27.9 months (0–132 months). While the median interval between primary kidney resection and resection of spinal metastases was 35.7 months (0–146 months).

Ten patients underwent surgical resection as treatment of tumour recurrence after irradiation of spinal metastases, 27.8%. The mean radiation dose was 47.5Gy and the mean time from irradiation to surgery was 9.6 months. For patients with a solitary vertebral metastasis at the time of surgery, the 3-, 5- and 10-year cancer-specific survival rates were 84.6%, 76.2%, and 76.2%, respectively. For patients with a solitary spinal metastasis and pulmonary metastases at the time of surgery, the 3-, 5-, and 10-year cancer-specific survival rates were 72.7%, 54.5%, and 27.3%. There was no local tumour recurrence in any of the 36 patients during the follow-up periods.

Motzer et al.74 described five prognostic factors marking reduced survival: Karnofsky performance status <80%, serum lactate dehydrogenase level >1.5 times the upper limit of the normal range, haemoglobin level in the lower normal range (13.5g/dl in men and 11.0g/dl in women), corrected serum calcium level >10mg/dl, and time from initial diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma to start of interferon-alpha therapy <1 year.

The study was conducted by dividing patients into three risk groups: favourable risk (no risk factors), intermediate risk (one or two risk factors), and poor risk (more than three risk factors). Only the presence of liver metastases was significantly associated with short-term survival after spinal metastasectomy (p<.001).

High or intermediate risk according to Motzer's criteria (P1/40.067) and the presence of lymph node metastases (P1/40.078) were associated with short-term survival. In contrast, the 3-year survival rate was 72.7% for patients with lung metastases at the time of spinal metastasectomy. They therefore supported the idea that metastasectomy of a solitary vertebral lesion in these patients is appropriate. Their results suggest that resection of spinal metastases may prolong survival in previously selected patients.

The most likely reason for prolonged survival in curative resection of spinal metastases, which undoubtedly compromise the performance status of the patient, is a further surgical procedure (Fig. 2).

The 5- and 10-year cancer survival rates for patients who underwent curative surgical resection of solitary spinal metastases from renal cell carcinoma were 69% and 58%. Liver metastases were associated with short-term survival, but lung metastases were not. For previously selected patients, vertebral metastasectomy can potentially prolong survival.

In the study Are older patients with solitary spinal metastases fit for total en bloc surgery?75 TES (total en bloc spondylectomy) was investigated in 78 patients with solitary spinal metastases. They were divided into two groups, group A (>65 years of age, n=32) and group B (<60 years of age, n=46). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of duration of surgery, blood loss, blood transfusion, or length of hospital stay (p>.05). The rate of perioperative complications in group A was higher than in group B (p<.05).

They observed that older patients may experience similar survival and local recurrence rates to younger patients treated with TES. The quality of life and neurological impairment of patients undergoing TES improved and pain was relieved. Although older patients have a higher risk of perioperative complications, this factor does not seem to lead to serious adverse outcomes. Older patients remain good candidates for TES to cure solitary metastases after careful and strict selective preparation.

Tumour type, rather than age, did influence patient survival after surgery, which also supports the results of the survival analysis.

The median survival time of the two groups that underwent TES was 20.6 and 23.0 months, respectively, meaning a longer survival than with palliative surgery (8.9–10.6 months).

For patients with secreting spinal metastases, en bloc resection may be an exceptionally useful surgical option. This technique has been described in the setting of pheochromocytoma, carcinoid, paraganglioma, choriocarcinoma, and fibroblast growth factor secreting phosphaturic mesenchymal tumours.15,57–59 These tumour types may only benefit from en bloc resection, as this approach theoretically eliminates the functional capacity of the lesions and provides better symptom control compared to subtotal resection.60

Finally, several rare tumour types have been shown to be candidates for en bloc resection. Optimal long-term outcomes have been reported in metastatic epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma,61 renal cell carcinoma of the spine,24 leiomyosarcoma,62 metastatic osteosarcoma,76 and acinar cell carcinoma, among others. However, due to the rare nature of these tumour types in the context of vertebral metastases, little can be definitively concluded about the overall superiority of en bloc resection in these cases.

ConclusionsEn bloc resection improves local control over intralesional resection for aggressive primary lesions.4,12,20,21,31 The associated improvement in overall survival may justify the increased morbidity of surgery, as these tumour types traditionally respond poorly to adjuvant treatment options.

En bloc may be an appropriate technique for carefully selected metastatic lesions, such as hormone-secreting tumours and solitary radioresistant tumours, but should be considered in the context of the patient's systemic disease status and the morbidity of surgery.13–15,50

Complication rates are higher after en bloc resection compared to conventional resection techniques.77

Patients who are considered for en bloc resection may be better managed by specialised surgeons in high-volume tertiary centres.23–25

Amy Yao et al.78 recommend en bloc resection for patients with a favourable prognosis, while palliative and cytoreductive resection is suggested for patients with an average or poor prognosis. En bloc resection had the highest mean postoperative survival time in the studies reviewed, while palliative resection had the lowest.

After the review of the literature up to the date of publication of this article, we conclude that the data shows that local recurrence is the worst complication, because it negatively affects the quality of life and prognosis of the disease.

Clinical caseA 75-year-old patient, with loss of neurological function over a few days. Frankel C. Diagnosed with renal carcinoma 3 years ago. Presenting pathological fracture at the level of T7–T8. Negative extension study (Fig. 3).

Clinical case of a patient. Negative extension study.

(a) X-ray and CT with fracture and kyphosis after pathological fracture.

(b) MRI with Bilsky 2 spinal cord compression.

(c) Intraoperative image with bilateral and prevertebral dissection.

(d) Stabilising rod and Tomita saws in position.

(e) Moment of turning out of the spondylectomy around the spinal cord.

(f) Resection piece and X-ray of it.

(g) Reconstruction and correction of kyphosis.

A 65-year-old male, diagnosed with Gilbert's syndrome. He underwent nephrectomy in 2006 for renal carcinoma. He had a preoperative Cr of 1.36mg/dl. Presenting metastasis at T7–T8 level treated a year ago with radiotherapy, new progression. Post-radiotherapy hypothyroidism. Nocturnal CPAP (Fig. 4).

Clinical case. Nocturnal CPAP.

(a) X-rays and MRI showing post-RT changes recurrence of lesion with compression of spinal cord and proximal part of left costal margin.

(b) Free right pedicle, free left pars, levels of decompression. If fractured, the estimated disease-free level should include the adjacent plates.

(c) X-ray of the resection piece of T7–T8, proximal part of the ribs included in the resection.

(d) Follow-up study at 6 years.

(e) Breakage of the rods, possibly as a consequence of RT, not anterior fusion.

(f) Revision surgery, stabilisation with 4 rods.

(g) 8 years of progression since first intervention.

Level of evidence II.

Conflict of interestsThere is no conflict of interest.